Our story today begins many, many months ago. In response to comments that my reviews were skewing too mainstream, I set out a call on social media for the weirdest books around. I can only review what I see, after all, and I live out in the sticks. The really weird stuff doesn’t hit the shelves at my local shop. So in terms of what fruits from the tree of comics happen to fall into my outstretched paw I’m often subject to the whims of sweet contingency.

All of which is to say, upon putting out a call for people to send me the weirdest stuff they had, two different people contacted me within the space of about 20 minutes for the purpose of pressing a copy of Prism Stalker: The Weeping Star to my bosom. Figuratively, of course; the book would not be available for months. An impressive coincidence, though, and a measurable testament to the very real buzz around this title.

The Weeping Star, out on August 2 from Dark Horse, is a sequel to the first Prism Stalker series, five issues from Image in 2018. Five years later the sequel appears, one graphic novel without prior serialization, but more or less the same size as that first series. The artist is Sloane Leong. This isn’t the first time I’ve looked at Leong’s work. That was 2021’s Graveneye, written by Leong but drawn by the talented Anna Bowles. Come to think of it, that review was also the product of another emphatic recommendation. Leong knows how to make an impression on people. Useful talent for a creator.

Our story begins on the planet Eriatarka, a weird and dangerous world. An interplanetary concern by name of the Chorus is colonizing the planet, a process which entails destroying a great deal of the native fauna and flora. In order to accomplish this, the Chorus are training soldiers. Our heroine is Vep, from the planet Inama, a member of a poor family who signs up with the Chorus for the promise of land on Eriatarka. It’s an old story, and Prism Stalker isn’t particularly subtle about it: join the Army, see the world, kill every living creature you meet.

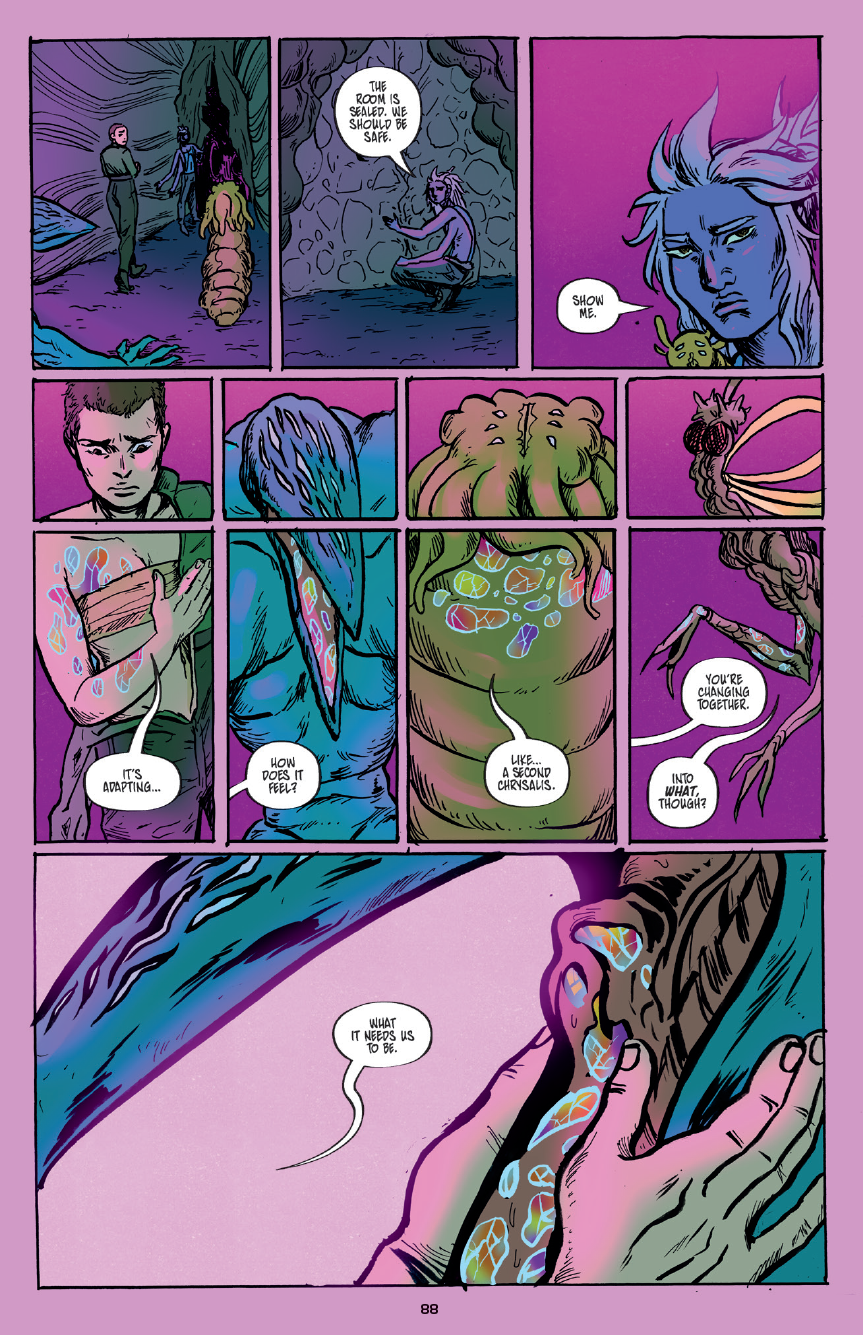

There is a special and apparently unique power to Eriatarka. Vep and her classmates are fitted with crystals that allow them to manipulate the pneuma, a special energy with a multitude of interesting properties. I’m old and my brain is hollowed out by worms, so the first thing that occurred to me was that it looks kind of like Doctor Spectrum’s crystal gimmick. I feel like you’re disappointed with me for even bringing that up, so we’ll move on without any further references to the Squadron Supreme. The cadets have these crystals embedded into the back of their hands, and are taught to use them to channel the different kinds of strange powers provided on this strange planet.

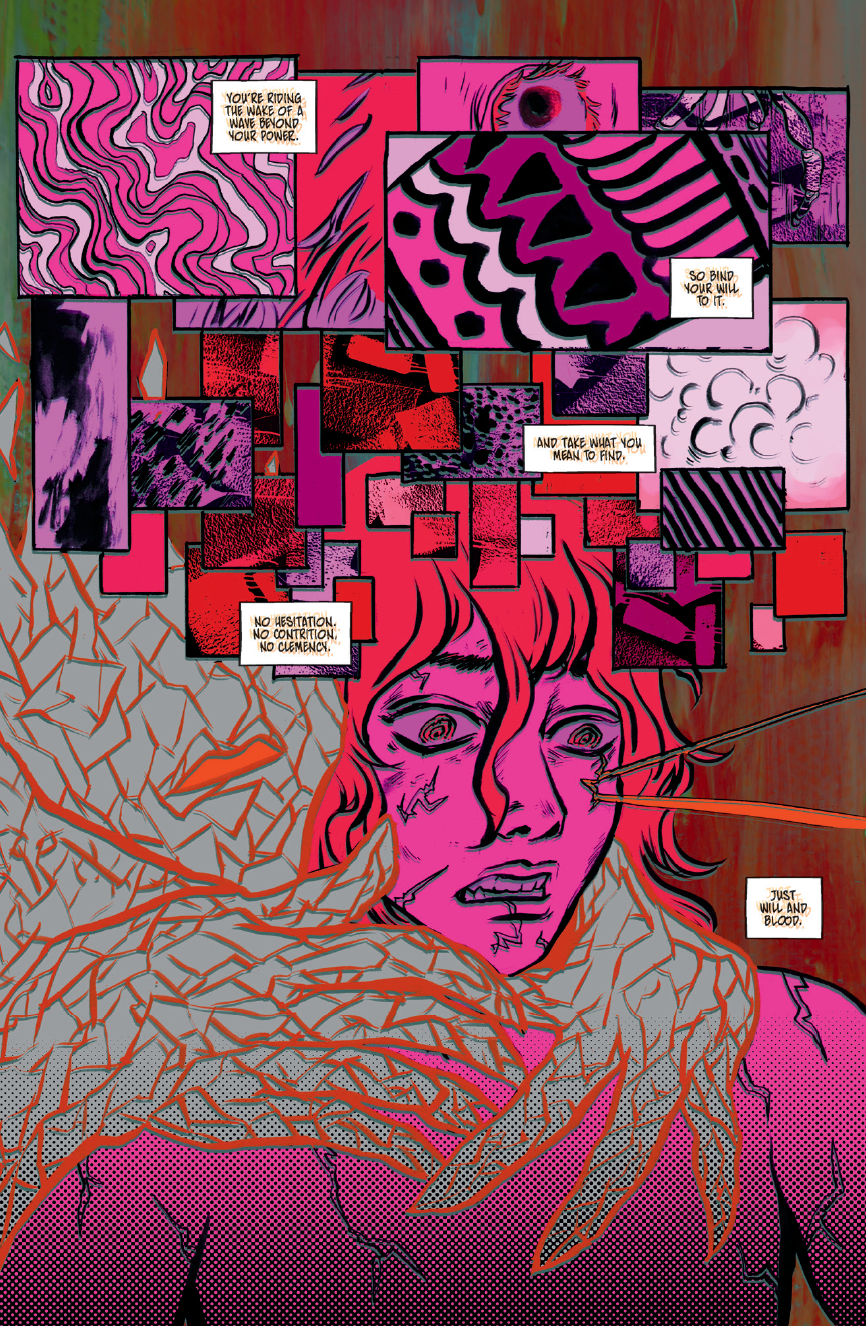

Where Prism Stalker excels is in translating the sensory detail of truly alien experiences into the flat medium of printed color. Notably, there isn’t any narration here to explain what’s going on. Most of the details can be picked up from context and dialogue, but there are no captions to translate events. We’re given pure metaphor presented in the language of visual spectacle. Play-by-play exposition would perhaps make the action clearer, but it wouldn’t make the story any better. If anything, it’d sap necessary mystery from what is, at its deepest foundation, an attempt to communicate enduringly alien ideas. I’m all for narrative captions, and I believe them to have become an underutilized tool in the contemporary storyteller’s toolbox, but there is nevertheless a great deal to be said for not spoon-feeding your readers. There’s a freedom for visual storytelling over prose: a drawing can just be what it is, it doesn’t have to explain or even describe itself. It can be weird as all heck all by itself.

An early sequence reveals the flexibility of Leong’s technique. A training run quickly becomes a dangerous contest with lethal stakes. Vep and her frenemy, the lupine cadet Sabrian, are pursued by a tsunami of blue slime crawling with bloodshot eyeballs. Although Vep and Sabrian make it to the finish line, it’s not without significant cost: not only do they lose the third member of their group, but they are themselves covered in the deadly slime. That slime apparently tries to eat them and induces hallucinations, which we see as a page of various shades of red, blue and violet shapes coruscating one on top of another, Picasso-esque forms fractured and split across the page like Colorforms. The captions—not narration—are instead internal dialogue, exchanges unmoored from context, words from within: “When you say ‘love,’ it sounds like distance. When you dream it is the color of surrender.... All that gilded glory, that bright, bloody splendor. You know your gods reside nowhere near gold.”

Another sequence features Vep, on another training exercise, confronted in the psychic realm by unpleasant truths. In response to the sensation of being held back by the cloying hands of family members, Vep pulls off her skin and crawls away as a glowing red skeleton, melting into a page made of shards of color and texture. She’s being strangled by her past. “Pain is a facet of intelligence,” the caption tells us, “the language of intention. Speak it with precision. Let everything you create recite the names of your suffering at once.” She is a constantly changing figure falling, on fire and fracturing like a crystal. If people still made black light posters, this would be a good place to start.

Leong’s color sense is revelatory. Every page looks sick, nauseated by a surplus of different shades, endless neons and magentas, some flat, some gradient. There’s so much magenta. Magenta’s a cheap special effect because you don’t need a fancy fifth ink to get that otherworldly sheen, it just naturally does that when you print a high saturation of red and blue. Michael Golden figured that out before just about anyone else in comics. There’s a reason why his covers always pop. Not magic, just high-saturation magenta.

If you know your way around sci-fi, it’s not too hard to figure out the problem, here: Eriatarka isn’t an empty world. Even though nothing appears dressed in a recognizable form of intelligence, every time Vep touches the pneuma she comes into contact with something else, something native to this world that knows how to speak directly to her worst insecurities. Although there’s an Octavia Butler quote at the beginning of the book, the sci-fi I kept flashing to was Lem’s Solaris. Perhaps the most iconic treatment of the question, “How would we ever recognize a fundamentally inhuman intelligence?” Chances are very good someone would try to murder it, if it were living on even vaguely desirable land. Or at least that’s the lesson of our desolate present.

There’s a lot here. The Chorus seems ineffably sinister in its machinations, but it also does very little to hide its intent. It has these cadets over the barrel. Sabrian, for example, joined up to get distance from their family, and because the Chorus can provide the medical treatment necessary to receive puberty blockers - to prevent them from growing into a mature female of the species, in effect a brood mare with reduced mental capacity. Like I say, not particularly subtle! The empire has no problem whatsoever extending the promise of necessary resources as extortion for those chosen to commit unconscionable acts.

The story climaxes with the graduation of Vep and her closest friends, simultaneous to the awakening spirit within Vep of the inhumanity of their purpose. Extended interior dialogues between Vep and the energies she wields assume a fevered, Ditko-flavored didactic intensity: “Your mind is a machine that makes emptiness,” she and we are told as images of endless interior vistas flash. “An emptiness you close up until it becomes a soul.... Our minds refuse to break the shell that demarcates our limits of perception. We are born greedy for a cage of our own making.” The imperial war machine opens its third eye.

If there is a future to the saga of the Prism Stalker, surely it will pick up from here, from the moment Vep comes into her own. She realizes her own complicity in allowing herself to be bent and molded by the Chorus into a tool for killing. Bent and molded by the same forces that destroyed her own home, in what she learns in passing was an industrial accident. There’s a lot more of Vep’s story to be told, a lot more of the story of Eriatarka. In the pages of Prism Stalker, Leong has created an indelible fantasy setting, ready and able to translate the most ineffable and startling ideas into lines and colors on the page of a comic book. A world of pure visual metaphor. I hope we get to see more of it.

The post Prism Stalker: The Weeping Star appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment