In 2020, I selected Jillian Tamaki as the very best comics artist of the last decade. Boundless (Drawn & Quarterly, 2017) and SuperMutant Magic Academy (Drawn & Quarterly, 2015) astutely capture the sensibility of the past two decades with remarkable intelligence. Skim (Groundwood Books, 2008) and This One Summer (First Second, 2014), both created with her cousin, Mariko Tamaki, exemplify the growing acceptance and the ascent of comics/graphic novels within North American culture. The new Roaming (Drawn & Quarterly, 2023) is my favorite Tamaki cousin/team work.

I interviewed Jillian in early April, as part of my project to record the contemporary alternative comics scene in Toronto;1 to demonstrate how a community of artists and mediators creates great art, rather than geniuses working in isolation. (I've also conducted interviews from the Toronto scene several times before on this website.) The interview covers more than just Roaming, although I could have asked much more about its rich qualities, such as its extremely effective change of layouts and background/page colors, witty dialogues, and amazing character designs.

-Kim Jooha

KIM JOOHA: I want to start with the quote from your introduction to The Best American Comics 2019: “Future readers, I hope you're OK... oh, how we worry about you.” Did you foresee something? [Laughs]

JILLIAN TAMAKI: It's actually great to remember that a lot of the issues that have felt oppressive now because of COVID-19 existed before, and were already super-alarming and scary. Trump was the president at that time. As I get older, I do notice that people's memories are short. They think that everything was great in the 2000s, everything was great in the '90s, everything was great before 2016, or everything was great before COVID-19. Then it's now, though - that's really bad. It's not really the case. It is interesting to hear that. If the first line in that essay is "Dear future readers, we worry about you," it must have felt really urgent at the time. And that was even before COVID-19.

In the introduction, you mentioned Trump, the polarity of the politics, global warming, etc. The same issues that affect us now.

And those issues were felt as terrifying then. There's a little bit of foreboding too. A lot of that stuff is coming to pass: abortion, etc. [Some of the] stuff that was sort of projected as bad things that could possibly happen aren't happening as well. I don't think it was my prognostication. I think I was just sort of communicating the pervasive feeling at the time.

Now to your works. Indoor Voice, a super-underappreciated work, was published in 2010 by D&Q. I had not known that you have such a long relationship with D&Q, because Skim is such a famous book.

Which was our first book [together with Mariko Tamaki].

Such an iconic book too, in the history of comics/graphic novels.2 Previously I told you how surprised I was because SuperMutant Magic Academy was so witty. Because in my mind—and I assume maybe for general comic readers’ mind—you are known from your collaborations with your cousin, Mariko Tamaki, such as Skim and This One Summer, kind of serious works.

Moody.

So I wanted to show you the "Shaq: I owe you an apology. I wasn’t really familiar with your game.” meme.

[Laughs] I thought that Skim was inherently kind of a black comedy.

That's interesting.

It is interesting to hear that the tone was surprising.

I wonder if it's because of how I got into comics - I came to comics in the middle of the 2010s. I started reading canons like “Best Comics Ever" lists and award-winners, so Skim and This One Summer are how I got to know you and your cousin’s work. Then SuperMutant Magic Academy came out in 2015.

I do feel like we are working in an industry that is intent on pigeonholing you. If a thing does well, they want you to do it again. And if you listen to them, you'll just be constantly doing the same thing. If you made a lot of money for somebody the first time, they want you to make more money for them. A different person wants you to make the same kind of money for them that you did over there.

I've been kind of aware of that, but also knowing that I have so many interests and I wanna do so many different things. And I have a short attention span. And I really don't wanna do the same thing over and over and over again. So [I'm] intentionally aware of that.

And projects are usually informed by the project that's finished. It usually zigs a little bit or zags a little bit. It's not to keep the audience on their toes. It's just making sure that I have a commitment to exploring these different sides of my creative interests.

I think I was pigeonholing you in a way. So I owe you an apology. [Laughter]

Not at all. I heard that about "SexCoven" actually.

How? ['Adult' content is] also in Boundless, which I think fits perfectly.

It's surprising for people after they had been familiar with my books with Mariko and SuperMutant. That it was “adult.” It had a different tone or had a sci-fi element in a literary way or whatever you wanna say. But it was a little grittier.

And that it was a small little book, and not like--

“Graphic NOVEL.”

Yeah! It's like, once you graduate to graphic novels, that's all you do. I definitely would not be happy just making graphic novels.

Yeah, it's a lot of work.

It's too much. Too much time, then at the end, you're like, "Here you go, hope you like it. It's four years of my life, whatever.”

If I were an artist I would be really scared, because for years you don't know how it will turn out.

Not at all! It's terrifying. Because it's so much investment of time, energy, all this stuff. And we don't know if it's any good by the end because you've been staring at it so long. You just have to trust the little decisions you made every day - that you made in the past, that they're kind of good decisions or successful decisions, and that it turns out all right, because by the end you have no judgment of it anymore. [Laughs]

At least in the film industry a lot of people work together, so you can listen to others’ opinions as you progress. But in “graphic novels,” it's only you.

Yeah, it's very lonely. [Laughs] I sit here like, "I have no idea if this is good, bad, middling." [Laughs]

Speaking of Boundless, it is one of my best books of the last decade because it is about cults. [Laughs] I think it reflects the general psyche of the last decade so well by talking about cults, technology and stuff.

What is interesting is that a lot of those stories were made close to one another, but they weren't set out with a theme. Themes arise without you-- like, not even trying. Because we're all pretty preoccupied with certain things in our lives.

It seems that Boundless is underappreciated because I didn't see it a lot on best of year lists. I don't know - maybe it was, but that was my impression.

I don't think so. There were a few, but yeah. I mean, it's short stories too.

Oh yeah! People don’t--

It's such a shame. I'm actually really into reading short stories, not even comics. My attention span is so short because of social media. [Laughs] There is something so nice about a short story, but it's not as sexy.

It's not a “Great Novel.”

Yeah, people want a hook into big themes, characters, ideas and iconography. You don't typically get that with a short story collection. I mean, it's easier to package, right?

But it is a shame because I feel like comics are just perfect for short stories. If only because they're more humane for people to make them, [laughs] instead of committing to 400 pages to a single character and story.

I remember when Alice Munro received the Nobel Prize, there was a lot of talk about how it's a win for short stories too, because it was the first time or one of very few moments when a short story writer got recognized.

She was definitely a major influence on me and Mariko at the beginning. She is ingrained into, like, what makes a good story, what makes a good character, theory…. She is an influence especially with Skim, for example - Lives of Girls and Women (1971). She's so amazing. I think her influence cannot be understated. You don't see her-- she's not forward-facing, maybe we forget about her a little bit. Unlike Margaret Atwood, who's public, she's very obviously not that, so maybe we kind of forget about her a little bit. But very influential to a lot of people.

I love that Indoor Voice is a tiny little book. I wish that D&Q continued the Petit Livre series, which Indoor Voice was a part of. At that time, you were kind of an emerging artist, and the series had a diverse lineup of you, Seth Scriver, Marc Bell, etc.

I love that Indoor Voice is a tiny little book. I wish that D&Q continued the Petit Livre series, which Indoor Voice was a part of. At that time, you were kind of an emerging artist, and the series had a diverse lineup of you, Seth Scriver, Marc Bell, etc.

Yeah! A lot of other people were from other disciplines too, like design. I completely agree. It's nice when publishers commit to emerging artists. I really wish that they would reboot that series. It is a more affordable and accessible book. It's not a huge graphic novel, it's not a magnum opus, it's a little thing, it's a nice introduction. That was a really great series and it's too bad that it doesn't exist anymore.

Indoor Voice is kind of hodgepodge. There's some commercial work there. What are my emotional ties with some of that work now? Not that much - maybe it was an important work for me at the time, but I guess that's good enough.

But I really wanted to start that relationship with Drawn & Quarterly. When they asked me to do that, I was like, “YES.” I just knew I had to do it, because I just knew that my work and the work I was gonna make in the future would fit so perfectly with them. I wanted to start any relationship with them that they wanted to do.

I love the very witty diary comics and sketchbooks from Indoor Voice. Less polished, in a way.

Yeah, we're not putting out a lot of books like this anymore. They definitely feel almost like 2000s-y. I loved that stuff when I was a student and I would buy it. I don't even know if I would buy a book like that now. [Laughter] Which is so funny. It kind of makes me sad. They're so freaking expensive. I wonder what the price was on this.

It was less than 20 bucks. Really cheap.

Yeah, and it was meant to be cheap, right?

All this is a little "mid-career." To watch the industries that you've been in crumble, modify, then come up again or not, or all these. There’s always a die-off of all these clients. The publishing environment has changed so much, even in just the time I've been involved with it. It's exhausting, but I guess that's always been. It feels accelerated now, but any time, anybody working in media for the last 30 years would say the same. But it's like, “Wow, you really have to be adaptable.”

Definitely. We talked about “mid-career" a bit before the interview. So, I will ask you again, for the record, do you feel like you're a “senpai” in the industry?

Oh god. I laughed the first time. I identify as "mid-career" more than “senpai.” [Laughs] And it feels like I can't call myself senpai. That's for other people. A lot of stuff with legacy, what other people think of you, and how your work is remembered, or if you will be remembered, what books are remembered, what books are mythologized, if you're mythologized, or if people study you - all that seems so out of my control. I guess there are people that make a lot of effort to ensure a legacy or something. But I feel like that's for other people to do or comment.

I think more about how I can stay interested, and hopefully relevant, and how to be a decent community member in a scene or whatever. Because in terms of “senpai,” that's something else that other people have to bestow upon you. There's nothing worse than a self-declared master. I have met many of those. It's obnoxious.

I just keep on plugging along. I just try to do good work. I also have to make money. [Laughs] But that balance has always been interesting to me. That's why I feel like I'm ultimately drawn to pop culture: how do you make something good within rigid systems? Popular and good is a huge challenge. I've always been admiring pop culture that is popular and good-quality and smart, or tiptoes because it's a very fine balance. I have found that challenge to be my challenge.

Speaking of "mid-career," I want to talk about your free mentoring program. It’s one of things that I love about your practice that you do for this industry or community. How did it come to you, and how has been the reactions?

Somebody did it a little bit before me: Marcos Chin, who is from Toronto, but lives in New York. Marcos was doing a similar thing over social media. I thought that that was a great idea.

When I moved back to Toronto, Canada, I knew I didn't want to teach in an institution in the same way, but I really like teaching. I've had good feedback from students. It's so rewarding helping somebody with their projects. So I knew it wasn't the teaching I didn't like, but I didn't like the structure I was doing it in. And I didn't want to just keep on replicating that. So the mentorship seemed really interesting. A new way of trying to teach and be in touch with emerging creators.

And it's been really good. But what's maybe more interesting is the readjustment of thinking about why I learn something and why I teach anything. Because I didn't want to just limit it to people that have professional aspirations. If they have, that's great. But they don't necessarily need to be like, "I want to be a full-time graphic novelist one day." It was open to people that had never gone to art school or were not currently in art school. Because if you're in art school, you have access to resources, in terms of feedback and all that stuff.

It was great, [Tamaki mentored] like eight older people. Sometimes people think to learn something, and if you wanna be good at it, you have to start young, but it's like, “No, man.” Art should be accessible to everybody. Art is enriching whether you do it as a profession or not. It's very corny, but it is truly empowering. I volunteer for an adult literacy program, and it really is true. Again, very corny, but it is very empowering to be able to tell your story, express yourself, and have people listen to you.

I really relate to it because before I came to comics, I was an extreme STEM girl - I kind of looked down on arts in general, especially fiction.

It's interesting you say that about looking down on the art stuff, because I feel like I was like that too. Even though I've always been an art girl. I guess I had a proclivity, then I got praise, then I did it more because everybody wants praise. I think talent is real, but only to a degree. Ultimately it's you building up your skill.

Definitely, even in mathematics that's true.

Totally. Little kids that you're praising, they get a little shot of adrenaline like "Oh, somebody likes that!" And you're just propelled forward with momentum that way.

Even when I was in kindergarten, I had little notes from my teacher saying, "You're gonna be an artist!" So people always told me that. But I was like, “Don't tell me I will be!” I railed against that for a little while, because I was like, “Are you saying that I'm not smart enough to do academic things?” Sometimes when you're good at a thing, you take it for granted and it's not challenging to you in the same way. So I resisted that. I wanted to be a [veterinarian] for all of high school, thinking I could just take all the science courses, which I only did okay at. I'm not a math person. But I wanted to prove to myself, maybe, that I could be other things if I wanted to as well.

I didn't have any model of an artist in my family, and to me that was, like, "Doing what you want all the time, that's not really a job. I want a paycheck. I want stability. I don't want a weird artist life.” It is funny now, because I'm in commercial art and a lot of my friends, especially in New York, are the most savvy, hard-working, cutthroat business people. Freelancers and freelance artists - you have to make that happen.

Yeah, they are entrepreneurs!

For sure! And you can't just sit on your ass and watch the money roll in. You have to really bust ass. It's ironic, because the freelance artists that I know are kind of the most busines- savvy people that I know. You have to be, because you're running a business.

I respect them so much. Even just doing self-promotion in this social media age, that’s so much work.

Yeah, and it's hard too, because you're selling yourself, your name and your ideas. For us, art is usually tied into self-worth, it's part of your identity. You're "an art girl," blah blah blah. You're trying to sell that, package that, and brand that. That's not for everybody.

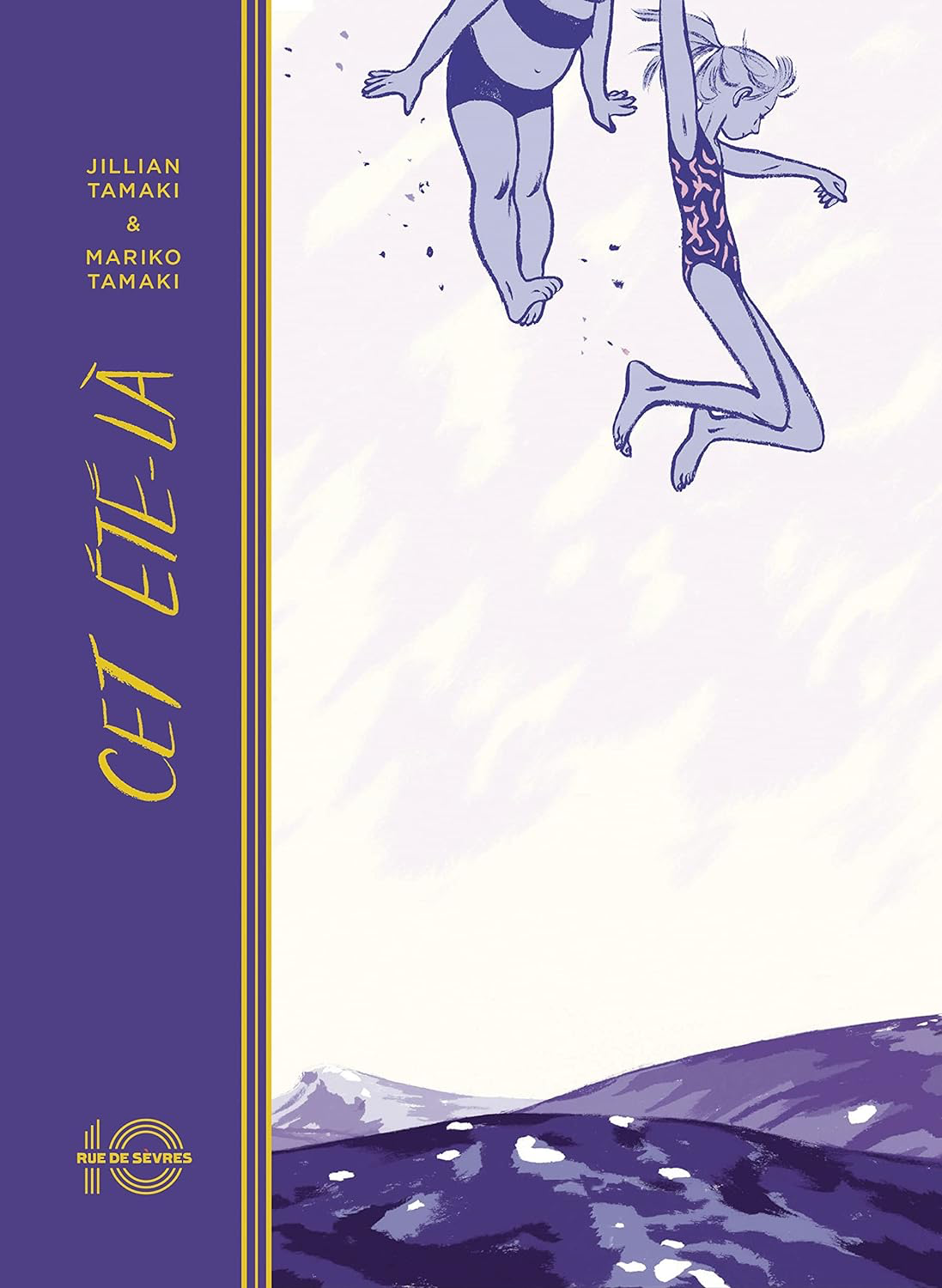

You've just mentioned how you love arts that are both popular and good. But your works have been both very popular and good. They've got a lot of awards and nominations. First, I just wanted to mention that. [Laughs] Second, is there pressure when your new works come out, because of how successful your previous works have been? And if so, how do you deal with the pressure? Every single work cannot achieve huge success, like - for example, This One Summer, whose French publisher just published a 10th anniversary special edition.

And they're often not necessarily tethered to quality.

That's 100% sure.

I never want to get to the point where I don't put 100% of myself into things I do. Even if you're half-assed, it's still a lot of time and effort. So I'm really, really protective of my mental health. Because I want to care about the things I do.

But you're totally right. There is pressure, because that kind of critical attention has been part of the story of my career in books. And that's been the way that the books have been promoted, almost. [Laughs]

Even early works like Skim.

Because they're not gonna be crazy blockbuster books, [those books are] more in that literary vein. Part of that commercial stream is through traditional ways, like reviews, awards, etc. It's just a system. It's kind of a little stream that you can go down, and that's the stream I'm in. [Laughs] For better or worse.

But it's fickle, because I've been on the other side where you're judging those awards. You very quickly see who wins awards is just who three or four people chose that day. And who you could all agree on to give the grant or the award to. So you can't take it too seriously.

I think I’m-- again, mid-career stuff, where you know cerebrally that not every book can be universally or equally loved and awarded. You know that in your mind. But sometimes in your heart, you still like to catch up, right? You don't wanna believe it. You want every book to be the best thing you've done, the most loved thing that you've done, the most lucrative thing you've done, and the most, like, awarded thing. Of course you want that. But it's just not gonna be the case. So I feel like "mid-career" is also managing those expectations and accepting the fact that the world is just not gonna view you in the same way, because we're also in an industry that really values newness and freshness. Fresh voice, fresh look, and new things. And that's very natural too, right? So as you move out of that sort of attention, it's a different kind of attention. There's a different kind of energy around you and your work. And that's just life. If you're lucky enough to be able to move into that new phase, and still be working in that new phase—because not everybody can and does—that’s for you to figure out how to manage your own expectations and work within the new energy: are you going to let that totally freak you out or are you going to rise to the occasion and continue to be brave?

To do another book with Mariko, some of those thoughts are sloshing around. I'm going to take another crack at it and try to grow from it, and not make the same book again, and make a better book, and try to do something different. Even not doing it traditionally, doing it on the computer, I'm like, "Some people might not like this."

Because people talk a lot about your lush brushwork in Skim and This One Summer--

Yeah, and I'm like, "Well, I'm not interested in doing it in a book at this moment." And I think this would be fun and different. That's cool to me. And that's the book I can make right now, 400 pages. That's the tools and that's what I can do. So I'm gonna do that.

You know that you're gonna lose some people who prefer what you have done [before]. But it's always that - you will be gaining and losing some of your audience. Never just accruing. If you change, adapt and grow, you will be leaving some people behind too. And that's okay.

What I love about This One Summer’s art is that it is so visceral. I’ve never been to cottages, I’ve rarely been to summer camps, even. But I could FEEL that otherworldliness and magic of the summer vacation place that is away from home. How could you create that feeling?

I didn't grow up with that either. We don't have that culture in Alberta, where I grew up. It's Ontario. That was a super-foreign thing. I didn't know what that meant, even. I had never been north of Toronto. Or, like, the Georgian Bay area or anything like that. I didn't know what that was.

So I had to go on a research trip. I had a friend that had a cottage. I stayed at her place. They showed me the area, took me on a boat, and we went to the little islands and all that stuff. I took a million pictures, and saw what the town and townspeople were like, because it was about the townspeople too. I went in with some images of the environment like the Group of Seven paintings that you're familiar with, but that's the mythology. I tried to capture the reality in the details, especially since I don't live there.

Even though the book is so specific to Northern Ontario and a culture of Southern Ontario or Eastern Canada, that book has been so widely translated. It's translated in Korea, and I saw people really loving the book.

Interesting. But you never know - that's why it's like a great testament to specificity. The thing with attempts to make something super-universal, and have a universal message, appeal, and universal themes, is that you don't need to necessarily do that.

Definitely. Because there's no way people in Korea have cottages in such a tiny country. I've seen on Korean Twitter people posting that famous dance sequence. Not even comics Twitter in Korea, just random, general Korean Twitter. [Laughs]

That's so cool!

And I so wanted to show off that I know Jillian Tamaki and met her on Twitter. [Laughter]

It's so funny because that book has a life of its own. I didn't really have anything to do with that besides making it. That's only one part of it: why a book takes off, why a book wins a thing. That's the machine, kind of. You're not really in control of that. You can point out so many books that are freaking amazing, and just stay smaller, right? There's nothing wrong with being small either. So you can't put that pressure on yourself to replicate what the machine does. It takes off and it’s its own thing. It's its own self, kind of separate from me now.

I remember feeling ambivalent when I finished that book, and being like, “Okay, well, I tried my best.” I didn't do all the things I wanted to do, but I did some of them, and like, “It's kind of weaker than Skim in this way, but stronger in this way, and I kind of succeeded there, but I kind of failed.” As I am with every single book I finish. I'm never finishing a book and being like, “That's great, yeah. Amazing work. I think I nailed it.”

I want to talk a little bit about Roaming, not too much--

Yeah, please!

I'm worried that if I ask you too many questions it will tire you out, because I assume you will have a lot of interviews and stuff. [Laughter] First, Mariko Tamaki is from Toronto, right?

Yeah, North York.

I just wanted to double-check the Toronto connection, because I heard that she’s not there these days.

She lives in L.A. now. She just moved there from Oakland. She's been in California for a while. She moved there when I moved [to Toronto], which is like eight years ago. It is kind of a bummer. I was looking for a place to live in the same city as her. But yeah, she's been down there for quite a while now. But she grew up in North York, and she went to the school that Skim is kind of based on.

And she went to cottages?

I don't think they had a cottage, but they spent some summers in the cottage country, renting a cottage every year. She went to college at McGill, so she definitely has this Eastern, Central Canada thing. That is not my childhood experience.

It’s interesting that you guys never lived in the same city. How does your collaboration work?

We never lived in the same city. In fact, we were not that close, because I grew up so far away. We only would come back to Toronto every couple years. My most vivid memory of visiting my family in Toronto was when my grandmother died. That was everybody getting together. We're not a very "family reunion" family.

Same. I think actually a lot of contemporary Eastern Asian families are like that. Like, white people are more into family reunions.

So I didn't grow up really knowing her. She was very visible because she published a book when she was in college, I think, and she was involved in a performance art group that got some notoriety. They were a fat activist—"body positivity" you'd say nowadays—performance art group here in Toronto. She was in Maclean's magazine, and on the CBC. So I would sort of see her from outside, like, “Oh my god, I have a really cool cousin that's an artist.”

The first time we worked with each other was for this little floppy of Skim through a tiny little Toronto literary zine. They got government grant money [laughs] to print these little books. It came up because Mariko was on a book tour with the editor of that zine. The editor, Emily Pohl-Weary, said, "I'm going to start a little series of comics that pair writers that have never made a comic and artists that have never made a comic to make comics." Mariko was like, "I have a cousin that just graduated from art school, and I'm gonna ask her if she would make a comic with me." So I was like, "Sure, that sounds great." Because I had started making comics anyway, living in Edmonton, and some of those comics are in Gilded Lilies [Conundrum Press, 2005]. That was a positive experience and we worked well together. It was such a cool experience that we were like, “Let’s continue that on.”

Are you guys the famous Tamaki cousins, the pride of the Tamaki family?

I don't know-- again, I think the family gets a kick out of it. I don't know if they read the books. This is going to show how funny my family is. My mom and dad, when This One Summer came out, were happy that it came out. They're like, "Amazing, great. It's not for me. But people seem to love it. So great!” I don’t think they connect with it on a personal level. That’s okay. It’d be stressful to have to please your parents artistically as well.

I love that.

Yeah. It's like you're doing well, because I read you're doing well. And you don't ask me for money. [Laughs]

I love that. [Laughs]

My parents were always supportive of my interests. But I always felt the pressure to make a living. I don’t think that’s a bad thing, either. I remember my dad saying, “I don’t care what you do, just don’t ask me for money.” [Laughs] I chose “graphic designer” because it seemed somewhat creative, but also a proper profession. You need to think about making money. It's not just a secondary trivial thing to consider; [to only consider] your passion for what you want to do. It's like money is important, and it is. To pretend that it isn't is really disingenuous.

Yeah, because art is in society. Art doesn't exist outside of society.

He was great in that he didn't really understand what design was either, but he's like, “You're pretty responsible. If you think that this is a good thing to study, I trust you that you're making the right decision.”

That’s amazing! More about Roaming. What’s the secret to be able to keep such a long and fruitful collaboration/relationship?

Some of that just feels like chemistry and luck. Kind of like a romantic relationship. Sometimes you luck out, and you are more compatible than you even know. God, maybe even not living in the same city would have been good. Who knows how it would have been different if we lived in the same-- you know?

I think that we're good at respecting the other's contribution. Because even with the books - the first two books were her script. Roaming, we wrote it together. We tossed the script back and forth. The other two, she came up with the script and gave it to me. But the artist puts so much of themselves-- and there's so much to say and write in the pictures. She was never controlling about, “Oh, it's actually, I was thinking it was gonna be more like this. This scene is about this, and I want this to happen.” It was always just so open that I never felt like a hired hand that was just making-- that's the worst feeling as an artist. You feel like you're completing somebody else's vision. You're just the vessel, the vehicle for somebody else and somebody else's story. You’re just a-- you might as well be a computer, right? And I've never felt that way with her.

So it's been very fun, and I feel like there's so much of myself in my teenage high school experience, even though I went to public school in Calgary and Skim is based on an all-girls Catholic school in Toronto. There's so much of myself in that, even though the story itself is not autobiographical - not that it's autobiographical for her too, but it's based on her experiences. More precisely, it's not autobiographical, but it's, like, the environment.

We've been very lucky with our publishers. They have been very-- fostering a good working relationship, in that they kind of let us do what we want. So it's been low-conflict. We've never really had drama in the publishing process, which would be really hard on a collaborator.

Because we are very egalitarian, and part of that has been very consciously breaking up the traditionally defined roles. For example, author and illustrator, or written by this, drawn by this, ink or pencil. Especially within literary comics-- well, a lot of comics prioritize the writer. Even mainstream comics too, right? The writer is like the top billing, and then it's everybody else. We were aware of that going in, especially because we were published through Groundwood Books, a kids' book publisher. So again, there's a real division between author and illustrator. We did not want to be divided up in that way. We wanted to just say, “We made this comic and we're kind of equal players in that.” That's where we started. I remember these conversations like, “What should we call ourselves?”

So we came up with "co-creator," where-- creator is such a common word now. But when we were talking about this, it felt like such a hoity-toity weird word, but it fit our purposes. Now it doesn't feel weird at all to say that. Something happened earlier on with some award, with her getting nominated and I wasn't. It really did force us to feel ourselves equally.

It was the Governor General’s Literary Award for Skim, right?

Yeah. And they've actually changed that award, I think. So we've always been very conscious of giving each other equal weight with the books and that has been good, really good. I think that it did pay off in a way.

One thing I hate about the North American comics culture is the centering of the writer. Not that I hate writers, but if you compare it to cinema, it’s the director who is in charge of visuals and the whole project, in a way. Comics and cinema are both visual mediums, so I think it should be that way [instead].

Now we just have our names on the book. We don't have roles.

I was actually gonna ask you that question, because I heard from Eric [Kostiuk Williams] that you also “wrote” Roaming.

Yeah. Which is different from our previous two books.

How did it work? Did you guys write together first and then you started drawing?

I wanted to make a book that was lighthearted, funny and fun - like, a romp. Something that was very youthful and energetic. I had this idea of going, [it] isn't a road trip, but like a travelogue, almost. Three friends in New York, and then drama happens. What would be fun to draw, almost building visuals around is-- I would love to draw them going to museums, and them flirting with each other. I was thinking about it, and I'm like, “This feels like a book I would make. It kind of has that vibe to it.”

Yeah, I can see that vibe. [Laughter]

So I'm like, “Do you want to work with me on this book?” And [Mariko] said yes. So I just gave her that-- it was kind of just what I told you. Just like, “This is the vibe I want: it's two old friends and then there's a new person, and the new girl basically fucks up the friendship.” That's like all that there was.

Then we started the script and outline. We passed it back and forth, talked about it over the phone, and made adjustments to that. We sort of volleyed it back and forth. Then at some point the script was done. Then, of course, it's the old school way of just, “I just need to take it and make the thing.” And that took a long time.

Interesting that you started this one. I can totally see the difference in style or “vibe.” It's much funnier, for example.

Have you seen the movie Withnail and I? It’s an ‘80s British film about two friends, and nothing happens in it. It's that kind of vibe. I wanted it to have a lot of that youthful energy. Being a fucking idiot. You don't know anything, because you're young. I've done that trip over March Break to New York when I was a freshman student.

Then COVID-19 happened. I was like, “I do not feel happy or excited. Will we ever travel again? Ever?” You just didn't know. Because this book is about travel, I was like, “I am not in the mood to do something energetic, lighthearted, fun and funny.” So I couldn't work on it for a while.

Oh my god, I had no idea that you worked on it during COVID-19, but of course you did.

Yeah, when I was in New York, I basically had to. I had to build the book from my memory. Because that's when I lived in New York, in 2009. Then from other people, other tourists’ documents.

Your Flickr shout-out at the end of the book.

Because they have every single corner of the city documented. If I ever needed anything, somebody had taken a picture of it or a video of it. It was like grainy photos, grainy video of a certain train coming in and doing that. Especially in New York, if you get a detail wrong - it’s such a New Yorker thing. “That model of train didn’t run on that line in 2009!”

I think I'm going to make a presentation about how I made a book like that. You don't even realize the depths of what is on the internet. Like the train schedule in 2009, when that train ran on that line, etc. You're drawing them going from 35th to the Natural History Museum, then they're on the specific train. What is the interior of the train design? Is it the orange seats or is it the blue seats? It used to be the orange seats, but when was it decommissioned? You'd have to go and see, like there was one instance where that train model only started running on that line like the week before the events of the book.

This is my favorite Tamaki cousin book. I’ve written that in my Goodreads review, as you can see. [Laughter] I love how light and funny it is, and I could relate to all three of [the protagonists]. I didn’t know that the book idea came from you, so it's not just to compliment you in front of you. [Laughter]

That's really good to know. [Laughs]

I think for some people it might be kind of surprising though. [The characters] are also freshman university students.

For sure. It's not going to be YA. You can't have that same expectation if you don't have that YA engine behind something, right? That’s just different. And we'll see what happens.

I definitely feel like some people will miss certain elements. Like there's no trauma.

Another reason I really love Roaming is those spreads. They are not just beautiful to look at, but also work beautifully in comics’ way. They are not just random spreads, but they really fit the narrative or the context of where they are.

There’s a million ways to do everything, especially in comics. There are infinite ways to present information, and present words and images. So you have to make limits for yourself, because you could go crazy trying to explore every little avenue. I'm always trying to be like, “What is the best way to show this for the story and the context, and not just a beautiful page, beautiful to look at, with the emotional resonance that's happening in the story with these characters at that moment?”

I think one of the easiest pitfalls that a writer-artist team can fall into is an artist just showing their craft out of context. A lot of superhero comics, for example. People talk about [this or that] artist, and [this or that] page is really beautiful to look at, but if you start “reading” it, the writing sucks, you can’t understand the thing, or it doesn't fit well with the narrative.

I wish readers would appreciate those spreads in Roaming, and how they come to be there in that precise moment in the story and [its] context, because I really, really love them and it shows the beauty of comics. I think a lot of people will comment about how beautiful they are. But it's not just about their appearance. I wanted to emphasize that. There are two spreads I especially adore: One is the "taking a picture" spread, which I think is some New York symbol thingy [the Flatiron Building]. Another is “subway travel” spread [see two images above], in the latter half. I think a lot of people will praise those two spreads. Maybe people will talk about the sex scene. [Laughs]

I know! [Laughs] I'm like, is this gonna get me--

More banned books?3

I don't think so, because - well, everything's banned. So you know, probably. If you think about it too much, you'll just get scared. It's already scary enough making a book, if you think about every possible reaction that everybody's gonna have-- it's very easy for me to say that in retrospect, now that it's all printed out. What am I gonna do about it? But it's true. You'll never do anything if you think about negative reactions. You will absolutely get negative reviews. You will absolutely get negative reactions. It's funny, I'm already reading some reviews of it where people are like, “Wow, like nothing really happens.” I'm of the school that if somebody touches my hand, that's a huge thing. That's the kind of book I make. You're never going to make anything that pleases everybody.

It's interesting how people say nothing happens. Because I feel like a lot of things happen.

That’s the point of travel, a short travel to a place like New York. You do a lot of things. And stuff happens to you. You're not often the one driving the stuff that is happening.

Where are they in the book? It’s so different IRL.4 I also like this empty, negative space on the page. I like this kind of very comics-way of detail.

[Laughs] Sometimes I get so obsessed with the layout of the book and the [printed item]. Then I have to remember that most people will probably end up reading it in some digital form. But I'm still so obsessed with the printed form. I never think about the digital reader. I'm always thinking about the physical book reader. I know for a fact that the way I lay out is not always so digital-friendly, because sometimes when I have to do stuff for a magazine, and they're like, "Hey, now make it for online viewing." It’s a huge pain in the ass.

Same! Even when I was reading Roaming on PDF, I made sure to read like two pages on one screen because it's really important to see the spread as a whole. I’m not a huge fan of Korean webcomics—I don't know if you ever encountered them—because the layout is not a thing there, everything is an endless scroll.

Do those ever get published?

Yeah, they rearrange. It’s different from artist to artist. Some old school artists start from the page and then they just put every panel vertically on the screen. But I think younger artists, they just start from the screen. They don’t think about the page as a whole. Then they rearrange them to a physical page when they publish books. And, sadly, a lot of them suck. You buy books because you love the work, you want to store it on your shelf and have it in your possession - in many cases because you are a fan of the work, as they are still available online. So a lot of fans who purchase those bad quality books get disappointed.

Interesting. So they actually do remark upon that? Because sometimes I wonder if people love that thing, so they want to support that thing. Sometimes it doesn't matter what it is, if it's good or bad. They're just like, "I just want to know that you're getting money because I love it."

They don't talk about it too loud because they want to support [the artists] and want good sales, and publishing in South Korea is very precarious.

Let’s focus on what’s important! To be honest, when I started reading Roaming, I was a bit skeptical because I don't like nor understand this fascination about NYC. But as I read it, I realized it's not just about New York. So, [addressing you, the reader] if you are hesitant to read it because of your hatred toward New York, like myself, I would recommend you read it anyway. [Laughs]

New York is an interesting place. It is exactly what you think it is, for good and bad. The worst things you expect, true. The best things you expect, true. And often on the same day. I have a complicated relationship with it.

Because I'm from a huge city, and there are so many of them in East Asia--

You're from Seoul?

Yeah. Almost every Korean is from Seoul because more than half of the people [in South Korea] live in the Seoul Capital Area.

Do a lot of people move there?

Yeah. Because most jobs in South Korea are in Seoul. We ourselves call South Korea "Seoul Republic."

Oh, it's a social problem.

Yeah, it’s a huge social problem. I remember getting really disappointed by Times Square. It was just another Eaton Centre. But, again, please read Roaming! I mean, no potential readers of Roaming would be influenced by this interview, but I just wanted to give a shout-out.

I think the NYC thing is just incidental. It could be visiting any mega-metropolis as someone from a smaller place. It could be about visiting Seoul!

I also want to talk about Our Little Kitchen, because I really love that book. Do you love cooking?

I am okay at cooking. I don't cook much anymore because I live with somebody that likes to cook a lot, so I don't cook nearly as much as I used to. But I love eating.

I asked the question not just for a joke. Reading Our Little Kitchen, I felt like “This artist really appreciates the process of cooking.” Was it your artistic intention to show that, regardless of what you really think of cooking, or was it your sincere feeling?

I only will choose a topic for a book that I feel like I can bring my passion to, whatever that means. I think all my books have a sensory element to them. That they're rooted in, that there should be some recognition in it, of a feeling, or an atmosphere, or a vibe, or a dynamic.

I volunteered in a soup kitchen for many years in Brooklyn. I was trying to capture that environment, which was very fast-paced, and people were really resourceful. They had to figure out what they were going to make on the spot, looking at what they had: things that just came in, somebody brought this in, and what's ripe. It was really like, “Okay, we can do that, and that, and that, and that. Everybody go do the thing.” Then you get pretty comfortable with-- because what you do is often similar: peeling potatoes, or chopping onions. You're doing that every week, and it's a big thing - you're getting pretty practiced.

There is a correlation to art-making a little bit. They're both skill-based, they're both hand-eye coordination, and there's something really gorgeous about watching somebody who's really good at cooking or preparing or whatever, just watching their hands and their movement. That's the same with watching somebody make art too. There's just something inherently pleasurable to watch somebody with skill perform that skill.

From the beginning of the parade of produce being prepared, I felt like I could hear the sound of the cooking from just reading the book.

That's what’s been fun about that book. It's a book that people really love reading to kids. It's got a lot of onomatopoeia. I learned it from a librarian when I was judging an award once that picture books are auditory. They're meant to be read out loud to somebody, or somebody who's learning to read it out loud. Very rarely are you sitting down and reading it to yourself. So the way that you are saying the words, and the words are-- they're written to be spoken, which is interesting. It's not like other books.

Similar to poetry.

That's why there's kind of a relationship there. That was something I was definitely thinking about with this [book]. That plays really nicely with comics, because it's a comic picture book, which has the different voices and all these different people coming together. A word balloon is so great because it's not one narrator. There are multiple people. So that was definitely something I was thinking about [with] that book: of speaking and that experience of reading out loud.

It was so sensory, and I've never thought [about that] with regard to kids’ books, because I don't read kids’ books.

I pay attention to them now that I'm in the industry. When we were going through all these books on the table, this librarian was like, “I mean, this book is beautiful, but it's really boring to read. There are too many words for this age group. They’ll get bored of the pictures. And THIS book is super-fun to read because it makes you look where the text is.” That was really interesting, because I had never really considered that element of it.

I also liked your postscript to Our Little Kitchen. It’s very witty. I recommend everyone read it.

I wasn't welcomed with open arms, or even a hello. You can start by peeling those potatoes. It was a busy working in a kitchen. There was just too much to do. I put my head down, did as I was told, and tried not to get in the way. I came again the following week.

This is why I love your writing, [it's] not romanticizing.

Publishers like “author’s notes,” and I think readers like them too. But as the author, everything is in the story. I also don't want to pose as an authority on environments like this. It was just an experience that I had and that I found really powerful. But I do agree, like - sometimes, publishers probably are right to give it some context.

Another reason I love the book is the place where things are happening. These days I’m reading stuff on sociology of the arts, and one of the classic studies of the field is that in kids’ books it's rare to see poverty, public community, community services, inequality, how inequality affects people, etc. - so-called negative things about society. But in Our Little Kitchen, it came so naturally. There is this appreciation of cooking, the process of cooking and produce. Then there is this communal feeling of cooking, eating, and enjoying time together in a public community setting. It was the first time for me to see this kind of environment, like a food bank and community kitchen in the kids' book or YA, although I'm not an expert. Why did you choose that environment as a topic for your kids' book, especially?

I think that the kids' books industry has recognized that.

Yeah, the study is from a long time ago, like in the '70s. A classic and old study.

I wouldn't say that my book is really special. But I’ve been often thinking about what community means, what city means, and what we owe to other people over the last several years, pre-COVID too. So that was maybe the backdrop. However, I really don't typically make books from that position, where I wanna Say Something.

It really was more that that was an experience that was so rich. It was such an incredible environment and a really meaningful experience to me that I don't have any more, and I missed it. I wanted to capture that place. That's kind of the nature of that place. So to not reflect that would have been pretty weird.

And all of my work is pretty realistic. People always ask me, "You draw different body types. Why's it like that?” I'm not trying to say anything with it, to be honest. To me, that's what the world looks like. So it'd be kind of weird not to. Not that you can ever replicate the world, but a lot of my work is trying to make little dollhouse versions of it. So it would be pretty weird to replicate the world with one body type, one ability type, one race, or something like that. You’re never going to get it totally correct. But because I'm trying to show the world with some degree of realism, it would involve diversity of everything. Race, gender, or age, etc.

I asked that question because this whole project is about Toronto and reading it made me think of the food bank around Toutoune [Gallery], where my little exhibition is, which is right next to Summerhill Market, a premium food market. And that contrast has been extremely unnerving for me.

Speaking of Toronto, in Torontoist, there was this article introducing you, and at the end of the article it says: “Who published her first? Montreal-based Andy Brown of Conundrum Press5 of course... who reprinted Tamaki’s City of Champions zine in 2006. Why can’t we have more cartoonists like this?” And now you're back in Toronto.

What year was it?

Let me check.

Because when that book came out-- I moved to New York in 2005. And that book came out in 2006. The City of Champions zine is about Edmonton, because I was living in Edmonton at the time.

It was 2010. The article was about Indoor Voice.

Okay. I was always going to come back here.

You mean Canada?

Well, Toronto, because I always wanted to live in Toronto.

Oh, now Alberta people will get mad. [Laughter]

I actually love Calgary. I'm working on a comic right now about Calgary. But I have always loved Toronto. I went to Queen's University [in nearby Kingston, Ontario] for a year. That was when I really started spending time here. I was like, “This feels great. I feel like I fit here.” It felt really comfortable. Even stuff like the space between people is the right amount of space. It's hard to put your finger on why you jive with certain cities versus other cities. I think about what makes a city feel good to one person and then too much for another person all the time. I always felt like Toronto’s got the right amount of weirdness, kind of a weird grit to it.

I was from a place that was-- it's not homogenous like people think it is, but it's not as diverse as Toronto. Nowhere is as diverse as Toronto. So that was amazing to me as a mixed-race person, being in a place that was literally mixed all up. I ended up spending 10 years in New York City, but that never really felt ‘real’? It felt like a fantasy land in some ways. I knew I always wanted to live in Toronto because it felt so right. And I have really loved living here. But it’s kind of a heartbreaking place to live. And has gotten a hell of a lot less accessible.

Yeah, definitely.

Very frustrating city to live in. But that's also the process of actually learning about a place, and not just enjoying visiting or being in the city. It's like being in a relationship. I think of the relationship you have with your city as a romantic relationship too. It's one thing to have a place on a pedestal, but living in it and being in it, you see it as a more well-rounded entity that changes. It's not one thing, it's many things.

That's so true. I think that's why I was a little bit disappointed in today’s Toronto when I came back a few weeks ago. It's like being disappointed in what's happening with my ex-boyfriend, ex-girlfriend…

Or friends, right? I mean, all my books are about friendships changing. And that’s really hard for me. So city changing, there is something inherently heartbreaking about it too. Even as natural as it might be, it's still hard.

You're doing something important for Toronto, because if there aren't a few people documenting it, scenes can just sort of scatter. That's the nature of scenes. Artists often aren't the best for recognizing the thing that's happening. It's actually a very specific kind of person that recognizes it for what's happening now, and not retroactively. So it's really important.

That’s kind of the point of the exhibition and project. That it's an entire community that produces the art, like you, Patrick [Kyle], Michael [DeForge], and Fiona [Smyth], as well as “institutions” like Koyama Press, the Beguiling, TCAF, Toronto Public Library [where TCAF is held, and which carries a lot of comics], and Toutoune, and networks of people that enable all this output. It's not some isolated genius.

That's partially what drew me as an adult. I kinda didn't want to stay in New York. Toronto felt so appealing because of the arts community. And all the artists that live here had an attitude that I found appealing and different, which was retaining DIY and independent sensibility. Because Canada produces so many creatives, but a lot of them have moved to New York, right? They moved to like, San Francisco, whatever. So the people that stay here are a certain kind of person. People that choose to stay to make an artistic life in Canada and Toronto, and don’t move out and try to go to New York. I really appreciate that sensibility. I admired it from afar and wanted to be a part of it.

It reminds me of the thing Marc Bell talked about. He's from London, Ontario, and he lives in Victoria, not Vancouver. So he talked about this "second city" thing, about those people who still remain in the second city, not having gone to Toronto.

Totally. It's funny because there's always a bigger [city]. London, Ontario is a big town to somebody living in the country or something. So there's always tiers of it.

I actually did feel like moving to Toronto was necessary for growth, which is ironic because you think New York is infinite and whatever. But it's not necessarily the place, it is the community around you, the scene, the environment, and the energy that you find yourself in. There was kind of a freedom and an artistic sensibility that was happening here that I could really like to learn from, like a commitment to artistic growth. Look at somebody like Michael [DeForge] that is constantly pushing himself, doing new things. Like a commitment to the art end of commercial art. In New York, you're gonna get really heavy on the other end. At least that was what it felt like. That sense of keeping things small and free was very enticing to me. I think that's why I always do smaller things too. I'm never just gonna want to do, like, big books. I would die.

I think that's why I love Indoor Voice so much. Because it's small work.

Speaking of Toronto, I want to talk about your great quote from Eric [Kostiuk Williams]’s new, amazing, amazing book, 2AM Eternal. I talked with Eric too about how smart your quote is: "Toronto is a city that seems hellbent on scrubbing itself of everything interesting about itself. I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say that this is an incredibly important document and will probably change a few lives too."

I think the first sentence is a really astute summarization of what's happening in Toronto. And the second sentence, and especially the later part, "will probably change a few lives too," is a superb [indication] of the power of art. Some people might say, "That's kind of corny," but it's actually true.

Well, let's talk about Eric first. I appreciate him so much. He is almost old school. It seems important to him that his work be part of the fabric of the city.

Same for Michael [DeForge]. He puts up his posters and stuff. And Marc [Connery] of Rudy.

Eric has the talent to do whatever he would want, but he makes his life's work to commit to community like that. I love that. And it feels rare. So I really admire that he sticks to it, because it's not the most lucrative thing to really commit to a subculture. Not that it's a tiny, tiny subculture, but queer club culture in Toronto is a smaller thing than trying to go huge. So I think that he's a really amazing artist, and I'm really glad that there are younger artists that are holding that interest still. Because I really feel like it benefits the city. I can't remember what your question was. [Laughs]

About your quote: “Toronto is a city that seems hellbent on scrubbing itself of everything interesting about itself.”

It's just very odd that everything people love about Toronto, Toronto seems to want to destroy. It is perplexing.

I never know what to tell people when people come to visit. I'm like, “Just walk around.” Just see a weird thing. It'll be really weird and cool. Or just walking down the residential area, just go pick a spot and walk there. What makes the city interesting to me is none of the landmarks. And if it is an interesting landmark, they'll tear it down. Hopefully it can retain some of that spirit that attracted me.

But what makes a city great for artists is how affordable it is. It's not complicated. What made Toronto really creative in the '90s and 2000s is that it was an affordable city to live in.

Yeah, especially compared to the States. But now I go to Metro to buy a crown of broccoli every day and it’s fucking three bucks!

It comes down to money again. People need space and time to make things. You take away those two things, and you're gonna get less art. And I'll never accept that society is better off with less art. Whatever form that is. Not even professional, just any and all. That's why all these incentives to keep artists, make art, all this stuff, are all tied into housing, cost-of-living stuff.

You don't need to pinpoint any group. All groups would benefit. No matter what their designation or who they are, or their identity, they would benefit from more sustainable, thoughtful leadership. What are our actual values? Do we want a diverse place that is culturally interesting and humane?

That's so true. Affordable housing is essential to everything.

Everybody. You don't need to carve out the groups. People can figure it out, they just need the time and the space to make things and be creative. Why does Toronto have good art cartoonists? Because it's been cheap to live and the Canadian government and the arts council fund artists. Again, very unsexy. Talking about the funding and grants is not very “cool.” But that definitely contributes. What do you value? What you value is what you'll pay for.

In one of the old interviews you mentioned that a lot of comic artists do illustration because it's more lucrative, but they don't actually like doing illustration, because you're at the mercy of somebody else.

But I actually do love doing illustration.

Do you love illustration?

Job to job. Here's a nice thing about "mid-career." It's a little bit more stability, a little bit more momentum. You don't necessarily have to get yourself on the radar of people. You can afford to be a little bit pickier. And I have more experience picking out jobs that are going to be good versus bad. I'm very lucky that I can make choices. It's not always just following my whims. I have to make money. But luckily I've been able to find a balance of making money and doing what I want. I am not interested in just talking to one audience either. It's interesting to talk to kids, but I wouldn't want to talk to kids all the time. It is interesting to talk to teenagers, but I wouldn't want to talk to them all the time.

* * *

The post “There’s A Different Kind Of Energy Around You And Your Work. And That’s Just Life”: Jillian Tamaki at Mid-Career appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment