How about Dwayne Turner? Ring a bell?

Oh yeah. That guy. What happened to him, anyway?

He hasn’t done much in comics for a while. But I regret to inform you, it’s because he’s in a better place.

By which I mean: Hollywood. So the story has a happy ending. Hits a couple left turns along the way, however. A gifted artist who struggled to find a project that could really sell his abilities. I don’t think the industry valued him at all. He also got unlucky a couple times, which is no small thing. That he left the industry altogether, in the position of pencilling a forgotten run of a later iteration of The Authority, and ended up from there working on Tron: Legacy and Halo would seem to attest to the fact that he had been severely undersold.

I first encountered him myself quite early in his career. Avengers Spotlight #26 (1989). Dwayne McDuffie writing. And I know your first thought is, wow, McDuffie and Turner, together up front, that’s a pretty good place to start a story. Rather gets your attention! But alas, it’s the very first part of a very long storyline, written and drawn by two men still in the early stages of their career, together based most likely on availability, hammering out the first story in a long chain of dominoes. A prison break with all the b-list super villains let out of The Vault for the purpose of trying to kill a bunch of super heroes, which they spent the next three months doing.

Anyway, McDuffie & Turner contribute four issues to this story in Avengers Spotlight, sharing a couple of them with late Don Heck Hawkeye material. Very readable - Heck was still getting regular work up through the end of the 80s. Not great stories, but readable.

I certainly thought they were great when I was a kid, because I was all in on Acts of Vengeance. That was the crossover McDuffie and Turner had been tasked with launching. Not a bad crossover, as these things go. Strong central premise, pretty basic - Loki hatches a complicated plot that ultimately hinges on talking a whole bunch of villains into trading enemies. One of the first of what we’d see as a contemporary crossovers, with shared trade dress across the line. They hadn’t yet used up all the good ideas for those. The earliest crossovers - anything before 1990, I’d say - the early ones, even, the poor ones, still approached the enterprise with a modicum of vigor. That’s roughly when the form began to congeal and become something confirmed as akin to a grinding obligatory chore for all parties involved. And even the better-than-average of the early crossovers, however such things are measured, still consist of vast tracts of stories very much like Avengers Spotlight #26-29. Slightly grudging cogs, if occasionally lit up by the presence of decent enough people.

Not completely without wit, I hasten to add. McDuffie couldn’t write a dull comic if he had to, even back when he was still learning the ropes. He already had the first Damage Control series under his belt, after all, one of the era’s highlights. McDuffie was writing a second Damage Control miniseries as a companion piece to Acts of Vengeance, the one that reveals the whole villainous scheme was also implicated in some devious financial doings involving the Kingpin making a lot of money in the construction industry. Crossovers were better when Dwayne McDuffie put them together.

The interesting thing about this span of Avengers is that technically the story - the whole story spanning three months of titles across the Marvel line - begins and ends in this obscure series. And the first bookend story in Avengers Spotlight #26 features the Wizard arriving at jail and being processed, and the second bookend story in Avengers Spotlight #29 ends with the Wizard, arriving at jail and being processed, and then getting beat up by a prison guard. No one likes the Wizard. His sole character trait is “difficult to be around.”

Anyway. Not interesting necessarily, but if you ever happen across these books they’re interesting for the talent involved. Worked with Chris Ivy over the run. Nice line on display here, not surprisingly a little funky in places. Not that distant from a young Klaus Janson. You can tell some parts of the drawing interest Turner more, and some of them are maybe a little bit rough. He challenges himself as well. Issue #27 features an early iteration of the all-women Avengers line-up idea that they’d return to in the new century, and it stretches him to a moderate degree. He puts a lot of work into getting solid expressions, even if the action is still stiff. I think the person we have to thank for that tendency is Gil Kane, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

Dwayne Turner’s career begins with Iron Man #209, in April of 1986. He draws the cover. How is it? Well, it’s a pretty good comic book cover for a rookie. His debut on interiors came the following month, in Spectacular Spider-Man #117. A Black Cat solo turn, written by Peter David, over Rich Buckler layouts, and with four different inkers - Bob McLeod, Dell Barras, Keith Williams, and Joe Rubinstein. Six people to draw a twenty-two page comic book usually means an all hands on deck situation, hardly a spotlight. But again, for the first time out of the gate? Already strong at stuff like clothing, hair, and texture. Already seems to give more weight to the quiet scenes than the fights, which is a tendency of these early stories. Like a lot of early Peter David, it’s a better read than you probably expect.

He draws one more comic book in 1986, Iron Man #212. It’s a visible improvement over the Spider-Man issue. He was one of six hands involved in drawing that first comic, but he’s on his own here, with Scott Williams on inks. Williams had been working for about a year at this time, already had the crucial formative experience of assisting Whilce Portacio on inks for Art Adams on Longshot. Turner’s struggling with his fight choreography, I think. Puts a lot of attention towards making sure fabric looks right, the occasional interesting use of perspective. Someone who clearly paid attention to his classes at the School of Visual Arts, but is still working on putting it together for a full finished product.

Turner draws two more comic books in 1986, shipping in the fall: Incredible Hulk #328 and Spectacular Spider-Man #123. That issue of Hulk holds the distinction of being the first issue of Incredible Hulk written by Peter David. Not even the first issue of his run, as Al Milgrom still had two issues of his tenure as writer left. But it’s the fill-in that got him the book. A done-in-one that features a striking sequence of Bruce Banner walking around the desert, with a nice bit of scenery. Inked by Tony DeZuniga, who seems sympathetic to Turner’s eye for texture.

That second issue of Peter Parker, also written by David, has his nicest work yet. He’s really good at drawing Spider-Man in that black costume. He struggles a bit with the domestic arena. This comic features the first meeting between the Black Cat and Mary Jane. A significant event in the character’s history undersold considerably, sad to say.

In any event, that concludes the earliest phase of Turner’s career. Turner started at Marvel while still a student at SVA, and this handful of comics reads like student’s work. He wouldn’t draw another comic for over a year, from Spectacular Spider-Man #123 November of 1986 to January of 1988 and the release of Thundercats #23. The penultimate issue of Thundercats, at least for the initial iteration of the franchise. They’re still doing Thundercats today, if you can believe it.

In any event I won’t bury the lede: it’s a very nice looking issue of Thundercats. The Thundercats are fighting some kind of underwater monster, floating around in submarines. There are a few sequences of the monster that stand out as being actually quite striking. Inked by Dave Simons, and looks as much like the cartoon as it can, an oft-punishing remit for many artists of any level of experience. Not a chore without some discipline entailed.

From there Turner decamps to DC for a period. It’s there he begins a brief period of collaboration with an older writer, Roger Stern. Stern was a veteran already by the time, popular with a lot of fans. A master of the old school, a writer of long slow-burn subplots that take years to wend their way through multiple different stories. And yet, for all his virtues still very much a man of the Bronze Age, writer of plot-heavy yarns, filled with exposition and often given to utilizing narrative shorthand to cover a great deal of territory in a limited period of time.

Turner worked with Stern on six issues - the first five of 1988’s Power of the Atom revival, the sixth the issue of Secret Origins that shipped the same month the series premiered. I won’t lie to you: they are extremely dry comic books. The Atom was always a dry character, partially I believe due to the main character’s temperament. Ray Palmer is a passive dude, and the single legible feature of his personal life is his absolutely garbage marriage, bad enough to be a major plot point in 2004’s Identity Crisis.

In any event, this series marked the return of the character to something resembling his previous status quo, prior to a long interlude spent killing very small people with a sword in South America. Palmer’s cocreator, Gil Kane, had drawn the character’s previous outing, 1983’s Sword of the Atom series. That’s the series that featured the Atom’s wife cheating on him, leading to him becoming stranded in the Amazon, coincidentally near to a hidden civilization of Smurf-sized fantasy people. See? What did I say about the man’s marriage?

The reason why all of this is important, is to lay down the context of a remarkably square run of comics. Not among Stern’s best, by any means. He’s a creator whose virtues can best be appreciated over long stretches of time. But a valuable experience for Turner, I believe. Stern’s stories are technically demanding in terms of plot-heaviness and eventful storytelling, in which many things must be precisely depicted in a fairly conventional way lest the thrust of the tale be lost completely. It strikes me as difficult work for artists who may not be fully invested in the material, but reaping dividends in terms of skill.

Best example of this phenomenon in practice would be Todd McFarlane’s run on Infinity, Inc., working with Roy Thomas. McFarlane finished up a surprisingly long run (1985-87) on the book the year before Turner spent six months at the company. By all accounts this was not material to which McFarlane felt particularly close. Plot-heavy stories with dozens of characters, all of whom have specific costumes. The reader will notice if any of the details are off, because the people who read those kinds of comics are there for the details. And thus we see, part of learning how - a big part of learning how - to be a successful commercial artist consists precisely of learning how to draw things you don’t care about with as much vigor as the things you love. Todd McFarlane learned a great deal from Thomas, and David as well, though I doubt he’d put it in those same words.

The most interesting aspect of Turner’s run with the Atom would be the pervasive influence of Gil Kane over the entire enterprise. Throughout that brief run on the character, you see a sustained attempt to engage with Kane’s work, something we see most clearly in his compositions. There are some angles of a shot that no one else but Kane - no one else in the history of the medium - would dare. He drew people’s heads at abstruse angles because he could draw people’s heads from every which angle. A hot dog, in the parlance, albeit in the rarified field of draftsmanship. However, after those six issues, Turner would be gone from DC, and for quite some time. He’ll return to the company under interesting circumstances.

He contributes two stories to the initial run of Marvel Comics Presents. Marvel’s surprisingly pretty decent biweekly anthology, usually split down the middle between new work from famous vets and first work from up-and-comers. Turner appears in issue #5, drawing Daredevil for a Terry Kavanagh script. That shipped the same month as issue #3 of Power of the Atom, summer of 1988. He does another Daredevil eight-pager that doesn’t make it into Marvel Comics Presents, but rather the Summer 1990 issue of the company’s inventory extravaganza Marvel Super Heroes anthology. The second appearance in MCP was in issue #15, five months later and shipping three months after his last appearance in Power of the Atom. A Jean Grey spotlight written by editor Bobbie Chase. Notable for showing a number of very small drawings of Jean Grey, dwarfed by every other element of the packed composition.

After that Jean Grey story, he’s absent for much of that year, between the Winter 1989 release of that issue of MCP and the fall run on Avengers Spotlight with Dwayne McDuffie. He puts the time to good use. There’s a sense of measurable improvement every time he comes to bat, exactly what you want to see from any artist, especially any young artist.

From there he shows up regularly on fill-ins. There are a couple issues of Conan the Barbarian, #228-229, from late 1989. Pretty decent, actually, by the standards of late 80s Conan. A two-parter, written by Gerry Conway, inked by Rodney Ramos. Conan gets involved with a table dancer, and ends up having to kill a giant serpent who lives in a lake. Notable for the fact that much of the story is spent in the presence of a woman in a bikini, and the story begins and ends with Conan getting a table dance. Basically everything you want if you want Conan stories, drawn decently. Seems like maybe he learned something from Thundercats, there, in the shape of pacing action for an ensemble cast with economy.

He draws Transformers #68, notable for also featuring his inks as well. The inks are fascinating! Heavy in places, not at all shy about putting black ink on the page. Very expressive with (I’m assuming?) a brush, almost reminiscent of Kyle Baker in patches. Transformers was at that point a book notable for employing multiple disparate artists working in shifts throughout surprisingly large stretches of its run. Always seemed it must be a nightmare to draw all those right angles, one after another.

From here to another significant assignment: Ms Mystic #5-6, published in the summer of 1990. Like almost everything Continuity published under their own steam it maintains the general preposterous if endearing air that accompanied most of Neal Adams mid-career moves. The first of those issues is inked by Mark Beachum and 'Crusty Bunkers' - which means in practice it was redrawn by a roomful of peoples - including Mark Beachum, who had been trained to draw like Neal Adams by Neal Adams. It certainly looks like a Continuity Comics book. You will need to pay me more money if you want me to read the words in the little bubbles.

The second issue is inked not by the Bunkers but the trio of Stan Drake, Ian Akin & Brian Garvey. Experienced hands, certainly. But also seemingly a lighter touch on the penciler. The work in issue #6 lacks the manic confidence of #5, but it also shows the penciler trying to metabolize the experience.

It’s one thing to be able to depict relatively complicated action with an ensemble cast - the most economic version of which can be seen in books like Thundercats or Transformers, books with a younger readership who (at least according to the tenets of editorial at the time) prized legibility above all else. The hard part is figuring out how to convey that same information via consistently interesting and novel compositions. A career riddle for good artists. You can see Adams’ influence smeared like a thumbprint across multiple generations of artists, having cracked that code as well as anyone who has ever lived, and was generous with his time.

Turner’s next Marvel work was more Daredevil, a four-parter in Marvel Comics Presents, shipping at the tail end of 1990. Written with layouts by Sandy Plunkett, inked by Chris Ivy. There’s a stiffness here that seems vestigial, given his progress over the last year, perhaps he’s bristling against the layouts. Not terrible, notable for representing the end of his earlier style.

For Dwayne Turner, 1991 would be a year of transformation. From a decent Daredevil serial in the warhorse Marvel Comics Presents - notable only perhaps for the fact that the last installment shipped in the same magazine as the first chapter of Barry Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X - Dwayne Turner graduated to the Black Panther, and a four-issue mini-series, Panther’s Prey. If you need to see at a glance, following the previous recitation of a long line of mediocre comics drawn by a man still learning his trade, just why Dwayne Turner is a force with whom to be reckoned, flip through Panther’s Prey, I beg you.

A frankly stunning book, from stem to stern. A book to announce a genuine talent.

It was also Don McGregor’s last story with T’Challa, barring I believe a back-up in an Annual in 2018. No creator cast as long a shadow over the Black Panther, for the first three decades of his career, than Don McGregor. He wrote for artist Billy Graham in the mid-70s for Jungle Action, the book that defined the character going forward. In the late-80s he returned and wrote the character for Gene Colan, a serial that run a full year in the biweekly Marvel Comics Presents, “Panther’s Quest.” In brief, a very long and very heavy story about the Panther fighting apartheid in South Africa. But without question worth the effort, containing some of Colan’s best late-career material, stunning and occasionally horrifying.

Panther’s Prey is a much different story. It’s more fantastic. There’s a dude who turns into a monster and grows giant wings, gnarly stuff. Deals with matters in Wakanda as well as with his old supporting cast in the United State, specifically Monica Lynne. A character who hasn’t appeared much in the new century, only briefly in the Christopher Priest run - but then, Priest used every part of the character, even the later Kirby stuff. His version of the character is fundamentally the character who made all that money in movie theaters, after all. Monica Lynne is not a presence in the life of that man, however, and the events of this story are part of the reason why.

Before Priest, T’Challa was known primarily through Don McGregor’s voice. McGregor tended to write heavy stories filled with serious subject matter - nothing wrong with that, certainly, and he was certainly one of the better writers to try their hand at the gestures in the vicinity of social realism that swept across the industry of the 1970s. Not a lot of humor in his Black Panther’s world, however, which stands out in hindsight. Perhaps that’s why Priest started where he did.

Anyway, I hear you struggling in your chair, you want to raise your hand, you want to squeal, there are certainly many words on the page when he writes a comic book. Yes. It happens. We shall just have to do our best to carry on.

Panther’s Prey was also, apart from its significance for McGregor, an important book for Turner. McGregor writes an extended text piece across all four issues of the book. Among other tidbits revealed is the fact that Turner’s dog at the time was named T’Challa. It does not take further input to infer Turner’s enthusiasm for the assignment. It was apparently a close collaboration between the two men. McGregor refers to multiple conversations with multiple members of Turner’s family besides Turner. A cozy collaboration, in other words.

The name that springs to mind, upon looking at Turner’s rather phenomenal leap here, is of course Billy Graham. It’s not a straight pastiche, not by any means. On the contrary. Turner inhabits the space with his own style. But there is a great deal of detail, illustrative texture undreamt in the earlier work. You can see he’s a lot more confident playing with dimension on the page, the Continuity influence plain. He learned how to ink really well, to judge from these results. The coloring is by Steve Mattsson, and finds the mood in Turner’s lushly rendered, endlessly inventive compositions. It looks very much unlike anything else being published by Marvel at the time, certainly. Almost seems airbrushed in places, there’s a similar saturated value here. At times, positively febrile work.

You can certainly see the hand of the writer in the shape of the similarities with stories, and his work with Turner, Colan, and Graham. Packed, eventful, lots of pages filled with tiny pictures of characters gamboling around and having philosophical discussions. Superhero comics at their best, Panther’s Prey is a work of deep affection for the character from all parties. Dense and eventful, recognizably an older mode but still vital.

Were Panther’s Prey the only comic book Turner drew in 1991 we would already celebrate the year as the most consequential of Turner’s career to date. But it was not the only comic book he drew that year. On the contrary, he returned to Marvel Comics Presents, and before even the end of Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X. Turner drew the Firestar serial that ran for six chapters beginning with issue #82, shipping in August of that year, the same month as Panther’s Prey.

Now, it’s nowhere near as good as Panther’s Prey, leaving me to think it may have been drawn prior. It certainly doesn’t look like it took anywhere near as long to do. It looks very much like what you’d expect a comic book hitting the stands in 1991 to look like, which you can’t necessarily say about Panther’s Prey. Not a prestige product, certainly. Not a bad story, for all that, for being one of the handful of Firestar solo stories in existence. Her against Freedom Force.

It’s not perfect, but it's commercial, either being done right before or even during his work on Panther’s Prey. Impressive work for a man with a busy schedule. He’s finally learning how to frame a face for emphasis in a panel, understands environment and dimension more. He’s comfortable building his compositions around depth, also one of McFarlane’s greatest tricks.

“Life During Wartime” - that’s the name of the Firestar serial - is inked by José Marzan. He’s been in the industry about as long as Turner, at this point. It’s decent work. Also of note, being written by two people - two editors at the company, Marc McLaurin and Marie Javins. Oh yeah, her again. A bit of an industry Zelig, that one, least once you start to sift the historical record.

Following the annus mirabilis of 1991 the stage was set for Dwayne Turner to make a major move. Barring a handful of obscurities such as a few pages in a pair of Excalibur Specials, and a Black Widow story for Marvel Comics Presents that was also Dan Slott’s eighth published work, Turner’s next major project was a major reboot of Marvel’s most prominent African-American character to that point, Luke Cage.

The return of Luke Cage to the Marvel Universe in the pages of Cage saw Turner working again alongside Marc McLaurin, frequent collaborator Chris Ivy on inks. On paper, the book should had performed. The return of a long-missing hero, a fan favorite, on a hyped solo book, creators huge fans, at the apex of the early 90s boom market, penciled by a guy who seemed like he maybe could break through to the big time with half a breath - what could possibly go wrong?

Many things could go wrong, and many more of those things did go wrong in regards to Cage. That’s why I alluded to luck, earlier. Little of the book’s failure can be accounted to Turner’s part, I don’t think, inasmuch as his art remains the highlight for so long as he’s on. But it must be said in no uncertain terms, the book did fail, manifestly, and for an ample host of reasons, which shall thereafter be enumerated for full historical context:

In the first place, winter of 1992 was a terrible time to launch a new comic. There was precisely one story that mattered in the world of comics at that point in time and it was the birth pangs of Image Comics, as played out across the comics press. There’s no way anyone involved with the creation of the comic could have known that at the time, of course. The book apparently took a while to get off the ground, partially due to the next reason.

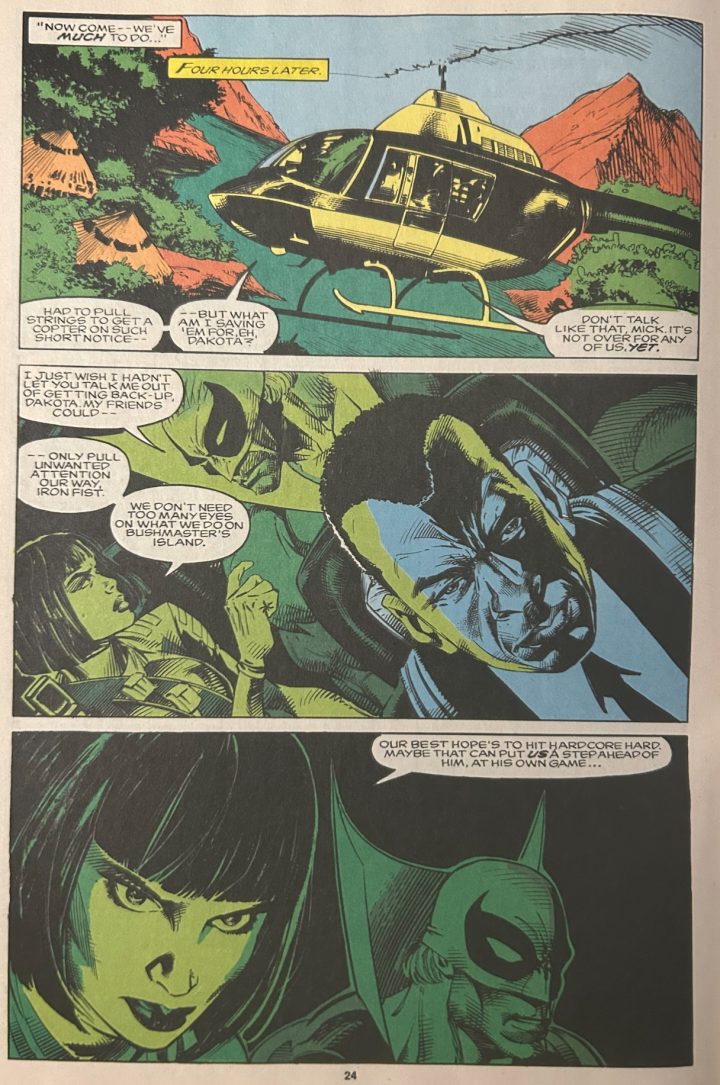

In the second place, Luke Cage had, in actual fact, been gone for longer than people realized: the final issue of Power Man & Iron Fist saw print in the summer of 1986, with the first issue of Cage hitting shelves at the beginning of 1992. The circumstances of the previous series’ ending contributed: writer Christopher Priest, then known professionally as Jim Owsley, working with the late, great Mark Bright, left the series on a big cliffhanger. Historically the kind of cliffhanger designed to provide a spur for another appearance, somewhere or other down the line, with another writer wrapping up the thread as a means to push the rock forward another month. That was how it worked. Except in this specific case said cliffhanger entailed a rather involved set of circumstances involving Cage being framed for Iron Fist’s murder. Baroque, high Bronze Age. No one had any interest in wading into the thicket to resolve the problem, so no one used Power Man or Iron Fist for five years. Danny Rand was eventually brought back in the pages of John Bryne’s Namor, of all things, although Luke was nowhere to be seen as Byrne resolved the Iron Fist cliffhanger by transforming it into a Sub-Mariner subplot. C’est la vie.

In the third place, Marvel kept promising a much bigger gimmick for the cover than what actually appeared. If memory serves, the rumor held that it was supposed to be chromium, or possibly lenticular. Back when these technologies were a big deal, and a new gimmick could make a tangible difference in the success of a book. I’m not kidding, as crazy as it must sound to anyone under forty. Those things mattered a lot, readers liked them. Up until they didn’t, of course, at which point - oh, boy. Anyway. Cage was a victim of that arms race, at least in passing. The book actually shipped, after some delays, with a relatively tame fifth ink cover, shiny silver-purple across the background of the image.

In the fourth place, Luke Cage’s first appearance in years was in the pages of The Punisher, in the months leading directly to Cage’s debut. This storyline would not prove the anticipated boost, given that the hook here was the Punisher "turns" black for three issues. Yes. I’m sorry if this is your first hearing about this. Interesting to note, Al Williamson inked that one, over Val Mayerik. Mike Baron was the writer, though Marc McLaurin is credited with assists. Marie Javins coloring, again.

In the fifth place - well, as if all of that wasn’t enough, the book just wasn’t very good. No need to sugar-coat. It’s interesting insofar as it isn’t a failure due to any kind of negligence. On the contrary, despite every element previously enumerated, the people making the book had a great deal of passion for the character and seemed determined to do well by his history. It’s not that the book was bereft of ideas - on the contrary, the book was filled with ideas. Filled with characters, filled with plots, filled with politics and subplots and angst and action - just, filled. So full, in fact, that there was no room for anything to breathe. There’s no form. No one writing this comic book had any voice.

We’re used to seeing comic books fail because no one involved cared enough. Cage is a rare beast, a book that failed for a number of reasons but not from lack of care. Indeed, you can see, for at least a few pages every issue, a glimpse of the book it could have been, more firmly in Turner’s capable hands. The book just needed to have less going on. Half the sub-plots and supporting cast should have been jettisoned. Give the art room to breathe. Establish a tone other than “very much.”

So why go into so much detail about this one failed Luke Cage vehicle? No one has thought about this comic in years. But the failure gives you the retail headwinds of the period. The failure had repercussions on the careers of the creators and characters involved, just like any failure. Conventional wisdom has always stood that Luke Cage doesn’t sell as a solo hero, not since the early 70s. They had to pair him with a Kung-Fu honky and ship the book every other month to make it to 125 issues back when they still sold them at the 7/11. Cage the book needed to make a forceful argument for the character in the Direct Market to have a hope of a chance heading into the retail firestorm of 1992. The finished product just didn’t.

Turner lands on his feet after this, more or less, as he manages a brief spell on Wolverine during Larry Hama’s long tenure on the Canadian. Issues #69-73. An absolute puffball, Wolverine and Rogue in the Savage Land for a few issues, poking at one of Claremont’s favored settings. Of no consequence whatsoever, considering it’s the last significant Wolverine storyline before the big crossover in issue #75, which was the one where they sucked out Wolverine’s adamantium.

But Larry Hama doesn’t write stupid comics. He writes silly comics, often, but even the silliest thing he ever wrote was still put together with a modicum of wit and a shovel-heap of skill. He wrote a lot of Wolverine stories, in a lot of different modes. This particular stretch is pretty standard superhero fare for 1993, taking full advantage of what Dwayne Turner knows how to do at this point in his career. He’s drawing a fully contemporary X-Men book, not ignorant of recent advances on the part of Monsieurs Liefeld or Lee, but still built atop a sturdy scaffold nonetheless. It reads like a gentle breeze.

From here Turner finds himself on less sure footing. He draws the first appearance of a new character, Hulk 2099, the less said of whom the better. You’d think he might pop up at Image at this point - and he does, however, only drawing a couple issues of Stormwatch, for Ron Marz. It doesn’t seem to lead to anything. He even pops up at Continuity, again, during that company’s last gasp in 1993, an issue of Ms Mystic, written by Peter Stone and inked by Neal Adams. Ms. Mystic appears to be a comic book by and for leg men, about which anything more must be left to the string theorists.

Otherwise, Turner lays low for much of 1994. A few small things here and there. He surfaces early Summer of the next year, across the street and at the helm of one of the most anticipated books of the year, from one of the industry’s most beloved creators. Friend, you know it to be true: I speak only of the Sovereign Seven.

Now, the shame of Cage was that it failed for many reasons, any one or even two of which it could have perhaps overcome, but the sum of which proved too much for the best intentions. The shame of Sovereign Seven is that it failed for one reason, and reason only. And, point of fact, it didn’t fail immediately. It lasted three years. But those were a very polite three years, and Turner left promptly at the conclusion of the first. Because Sovereign Seven was terrible.

Sovereign Seven was the first major superhero story from Chris Claremont following his unceremonious departure from Marvel in 1991. He popped up at Image thereafter, writing arcs for both Jim Lee’s WildC.A.T.S. and Marc Silvestri’s Cyberforce, a well as having a bit of a leisurely stroll on a big Aliens/Predator series for Dark Horse, drawn by Jackson Guice and Eduardo Barreto. It sounds better on paper than it is, I plowed through it a few decades ago and it didn’t come together for me. Claremont could write his own ticket in 1995, which we know because he did exactly that: he went to DC and carved out a novel new kind of contract, enabling him to write a new superhero book set in the DC Universe, while still retaining something resembling ownership. In practice, a version of the Vertigo participation contract, only he could crossover with Superman. Power Girl joined the team for a while, yet another era of that character’s life ceaselessly complicated by external circumstances.

That was after Turner’s time on the book, however. It just wasn’t very good. It had its fans but even they tend to agree it's not very focused, full stop. It wants to be back at the top of the line so badly that it falls completely on its face at the starting gate. And that’s a damn shame, because the comic could have been good, it should have been great. But it wasn’t. It’s barely readable. The first issue of Sovereign Seven reads like running into a brick wall. So many new characters. A whole team of villains, the Female Furies and Darkseid; who stops to have a cup of coffee, to give you an idea of the tone. A perfectly Claremont idea rather adrift in a terrible story, the tale of just about everything the man wrote for DC.

If we’re being frank (and why not, at this remove?), they should have just done Batman. Claremont should have done himself and Dwayne Turner both the complement and favor of writing Turner a Batman book in his mid-90s prime. Because that would have probably slapped, even if it was terrible, even if it put Denny O’Neil in the hospital. Sovereign Seven does not slap, at all. It rather abjectly does not.

That’s not Dwayne Turner’s fault, not at all. You would have said “yes” to Chris Claremont in 1995. You might say “yes” to him today, he still writes as much as they’ll let him. He’s improved since the 90s, I should say, in fairness. He didn’t write any truly great comics when he returned to Marvel at the end of the decade but he wrote some readable ones, and you can’t understand the magnitude of that achievement until you read a book like Sovereign Seven. He really did forget everything he once knew. About how to start a story. About how to hook readers, give them something interesting to hold in their hands right up front. How to withhold a lot more.

And most importantly: how to put your artist first in your estimation of the story. It is universally true that every artist who worked under Chris Claremont, during his first tenure at Marvel, benefited from the association, and learned a great deal. John Romita Jr. seems to have had a miserable time on the book, but for better or for worse it was Chris Claremont who taught him how to draw comics like someone who wasn’t his father. It was a demanding subject, but everyone who worked on that book - and even the spinoffs, and sometimes even the fill-ins - became a star. For better or for worse. And Dwayne Turner had every right to expect that, perhaps in a vacuum, but it just didn’t play out that way. There are too many words on the page and too many people talking. Everyone’s costume looks the same. People are standing around. You’re wasting your artist to draw this.

It’s a grim cavalcade. It could have been something, but it wasn’t.

Thankfully, however, Dwayne Turner’s nineties don’t end with Claremont’s folly. There’s even an unlikely hero for this leg of the journey. The man directly responsible for commissioning the best work of Dwayne Turner’s career: Todd McFarlane.

Oh, yeah. That guy. I wasn’t just mentioning him earlier for no reason. McFarlane got his start on more or less the exact same rung of the ladder as Turner: drawing dipshit DC stuff, learning as much as he could from the older writers writing stale stories. Which were nevertheless challenging and educational experiences for the journeymen artists tasked with the execution. McFarlane took off like a rocket. Turner struggled, despite what looked on paper like an enviable career path: already worked on two of his favorite characters - Black Panther and Luke Cage, worked with Chris Claremont and Neal Adams, Wolverine with Larry Hama. And yet somehow, it didn’t work out the same. He’s absent entirely from the conversation, because instead of picking up heat on a tertiary X-Men spinoff he’s spending 1991 on his career passion project: an unimpeachably gorgeous square bound limited series written by a seventies guy that, I am sorry to report, was not widely greeted as a resounding success upon release. Who knew 1991 was going to be that important? It kind of was that important.

So, when I say Todd McFarlane airlifted Dwayne Turner from Chris Claremont, I mean there was one month between the release of Sovereign Seven #12 in July of 1996 and the first issue of the ongoing Curse of Spawn in September. There had never been a second Spawn ongoing series. A few spin-offs, a few good artists cycled into the Todd McFarlane pipeline. Todd had an eye. Still has an eye. That’s the bitch of it. Greg Capullo was good when he started working for Todd McFarlane, and when he left Todd he was capable of truly great things. He also drew a lot more like Todd McFarlane, which didn’t hurt, although its worth noting Todd draws a lot like Greg Capullo these days. Marc Silvestri drew the twenty-fifth issue of the regular series. The strangely compelling Bart Sears did the first couple issues of Alan Moore’s Violator, which I will go to my grave believing Alan Moore must have enjoyed writing a great deal, don’t you dare spoil my glow here. Mike Grell stopped by for the oddball but endearing Spawn the Impaler. There weren’t a lot of people who’d written or drawn Spawn even as the middle of the decade wore down. It was a small club and Todd picked every person in it.

Which seems like it shouldn’t have been a big deal, out of context. But that’s what the whole movement was for. Spawn was his, everyone involved knows that going in. He was going to take care of his guy the best way he knew how. Sadly, it did not involve actually drawing the book, which was always its biggest appeal, full stop. However, that qualm aside, he is currently, as of this writing, producing an entire line of Spawn comic books. He’s somehow kept that guy going while the rest of us were getting wasted on Boone's, whatever else you want to say about him.

And when it came to expand the franchise he looked around and he found a guy who had spent the last half-decade underperforming to a spectacular degree. And we know, categorically and with no hesitation, he was underperforming, because when given carte blanche to produce a book for Image he drew Curse of Spawn. I don’t want to understate the degree to which this book hits. You need to see it for yourself, as I’m guessing you perhaps have not. You need to come to a place in yourself where you can accept the fact, incontrovertible through decades of empirical evidence, that the Spawn aesthetic has its time and place, and has its boosters as well. It’s a mood as much as anything, and just that insistence on mood seems the missing link between the outsized success of McFarlane’s work and that of his closest peers. He was all about mood even if the stories weren’t all there. Spawn didn’t, and doesn’t, have plots, per se. But if you’re there to see an artist strut his stuff, and show off his dude, Todd will show you a good time. Curse of Spawn is the the perfect articulation of that ethos in performance, drawn by an artist hired for the purpose of being a hot dog. There are worse attitudes to have going in to a book, but that you’ve been hired to go as far out as you can go. And that was how they sold the book.

If you’re old enough to remember Karen Berger editing mainstream horror titles with large newsstand distribution - the first Reagan administration - you might remember seeing Todd’s name a few times in the letter columns for those books. He was a devoted and discerning reader of the last generation of mainstream American horror books, and has been trying to catch up to Berger for the entirety of his career. Just look at who he hires to write his comics.

I mean, yes, we’ve all read the depositions. He had problems as a businessman. Hopefully he learned something from the public dissection of his odious legal proceedings. Image itself was ran exceedingly poorly for years. This is all public record. He somehow managed to keep publishing comics, so clearly he at least understands that part of the business. His artists tend to be really loyal. That’s not nothing, in this crazy world of comic books. You might even say thats half the game.

This was going to be the book for Dwayne Turner, after all these years, it really seemed as such going in. And it was! No suspense there. Maybe it didn’t last as long as it could, I don’t know. All that boom market stuff from earlier in the article? Gone. All uphill now, so it probably didn’t sell as well as it should have. Curse of Spawn lasted 29 issues, of which Turner drew the first twenty four, which segued into another Spawn ongoing, Spawn the Undead, also still drawn by Turner, written by Paul Jenkins. That lasts another nine. That’s a great deal of Spawn for any one man to draw - thirty three issues, notwithstanding a couple odd jobs around the edges. Enough to make you see what had been building.

Turner is supercharged. He’s inked by a number of folks throughout, most prominently Danny Miki, but also Chance Wolf and even Todd himself shows up for a few pages. All invested in making Turner look like a million bucks. Now, putting my cards flat on the table: I’m a fan of Danny Miki. He still works. He still has haters. Think about that a minute. Think about the shrinking role of the inker in modern comics. Used to be a seat for real hotshots, people who could transform the look of a book with just ink on paper - Janson, Sienkiewicz, both Severins, Williamson, Chan. What’s more, people who could teach and develop the younger pencilers with whom they were paired. That emphasis has been lost, in the digital era, in the era of people who ink their own work. Editors without as much of a comics background don’t know how to use inkers as pedagogy, don’t know how to cultivate a stable of distinctive inkers who can jazz up meat & potatoes material and pull up their collaborators in the process. That’s how ink worked for decades but that’s not how the ink works now. That Miki remains polarizing is a sign that he remains a presence on the page, which is what you want to see from an inker.

Miki learned a great deal from McFarlane, as he had from Scott Williams - how to put all the little lines on the page, but with some character. Williams rose to prominence because he was reputed to be slavishly loyal to Jim Lee’s line. At the height of the 90s, working with Chris Ivy and even inking himself, you can see Turner looking for a line like Jim Lee’s line. Like a lot of artists in Jee’s wake they subsequently discovered it wasn’t always the most flattering line. McFarlane’s style - at least, his style through his Imperial period - was built around ingratiating the reader. If it seems smothering or fussy, the pencillers who work under him don’t seem to mind. They appear to lean in, which is really what you want.

Yes, it is Spawn, so you must steel yourself for an immersion in that suite of imagery - demons and angels, ghouls and maniacs, the occasional mob guy or government hit man, all covered by a patina of grime. It’s Todd’s game, but he gets consistently good work out of great artists, so he has to be doing something right simply on those terms. If you were looking for Spawn, but with more theology and more gore, drawn by a hotshot with a righteous axe to grind? Curse of Spawn is the book for you.

There’s one side-trip during the initial run of Curse of Spawn, a short feature, with Miki, for issue #9 of The Batman Chronicles. Written by Chuck Dixon, it’s a nice looking Mr. Freeze piece. Chronicles was an anthology with a killer lineup through its run - just this one issue features the Turner / Miki team rubbing elbows with Duncan Fegredo and Cully Hamner on separate features. Nice lineup for a Batman comic.

Turner’s run on Curse of Spawn was mostly written by a man named Alan McElroy, with an appearance by Brian Haberlin. McElroy a comics guy, but a screenwriter. Showrunner for HBO’s Spawn series and screenwriter for the 1997 Spawn film, clearly someone McFarlane trusted. A horror guy, wrote Halloween 4 and the first script in the Wrong Turn slasher franchise. McElroy had a weird run around the turn of the century, after 1997’s underperforming Spawn, his next three features were the first attempt to adapt the Left Behind franchise - the Kirk Cameron one, not Nic Cage, because we live in a world where you need to specify - Ballistic: Ecks vs Sever, and then Wrong Turn. They’ve made six of those, incidentally.

When Turner picks up on Spawn the Undead, it’s a different vibe. Paul Jenkins is writing, fresh off Hellblazer, so it’s solidly constructed and moody. Set in the present day and featuring the regular Spawn, it’s got a separate vibe than Curse of Spawn, which veered between different members of the Spawn supporting cast and different dark fantasy environments. Spawn the Undead is a very different kind of Spawn comic, more somber and serious-minded, if you can imagine such a thing. The nine issues is defined by a series of memorable character pieces featuring a focus on normal people, work to stretch the best of artists.

From there, Turner pops up on covers more often. In that capacity he gets to draw Ellen Ripley flanked by a squad of Predators and holding the severed head of a T-800, for Aliens vs Predators vs Terminator. Which was probably pretty fun. Draws a month of Superman covers at the precise turn of the century, as well for the Green Lantern vs Aliens matchup - covers for Rick Leonardi interiors, there.

The next work of note is a book for Top Cow, late 2000, called Butcher Knight. I’ve read Butcher Knight. I wish I could say Butcher Knight was better than it was. Top Cow believed in Butcher Knight, they pushed the new series with a crossover event featuring Witchblade, the Darkness, and Lara Croft - yes, the Tomb Raider herself- then, still in her first flush of popularity. An Arthurian theme, but also frankly too much going on. They clearly had a lot of ideas but not a lot of structure. Not an unfamiliar story for Top Cow. They followed the success of Witchblade and The Darkness with a series of underdeveloped, artist-driven books that struggled to find legs in a punishing retail environment. Slot Butcher Knight next to Ascension and Spirit of the Tao, thrown into the perpetual bear market without a lot of ballast.

Accordingly, the last act of Turner’s comics career is fraught. He and Miki finally makes their way to Batman for a story of substance: Batman: Orpheus Rising, launching into the cloudy skies of fall 2001. Cocreated with writer Alex Simmons, Orpheus is the new kid in town, fighting crime in Gotham and butting heads with Batman, of course, because that’s what Batman does. So far so good. Orpheus is Gavin King, trained by a secret society and given and high-tech helmet to help him fight crime. More to the point, the character represents a conscious attempt to insert a different kind of character into a milieu that had been, stubbornly up until the turn of the century, quite white.

In issue #3 of the series, at the outset of a brief but tense conversation, Batman asks Orpheus straight out, “so, what is it you think I can’t do?” To which Orpheus replies, “represent my people.” Batman responds, as you might expect, “obviously, you don’t know me. I don’t play favorites, and I protect everyone.” True as far as it goes, certainly, but Orpheus’ response is worth excerpting at length:

I’m not talking about protection or takedowns. I’m talking about what they see when you and your Bat-Squad hit the streets, or when the Justice League makes the Six O’Clock news. They may see heroes, humans and aliens … but they don’t see themselves. They don’t see their people defending the streets, the country, or the planet. So many don’t believe they’re a part of the solution - especially the kids. They don’t realize we can make a difference too.

A familiar sentiment in 2025, perhaps, when questions of representation are poised at the forefront of discourse. But please, do not doubt, it was a familiar sentiment in 2001, as well. Opponents of pluralism in the public square love to pretend these are new questions when they’ve always been front and center.

Orpheus Rising is decent. Drier than you’d hope for from Turner, at this point in his career. A lot of footwork is expended on setting up a status quo for the fellow, mostly sidestepped going forward. His only major impact on the larger Batman saga followed two years after his premiere, during the crossover War Games (2004-05). Now, roughly half of you just groaned because even if you don’t remember exactly what I’m going to say, you can already sense the landscape. To wit: War Games is one of the worst Batman stories of all time, inasmuch as these intangibles can be collated. The primary reason why this story has been consigned to ignominy is the graphic, extended, on-panel murder-by-torture of prominent supporting character, Stephanie Brown, AKA the Spoiler. Distasteful and distressful, emblematic of a period at the company symbolized by shock tactics and sensationalism, often with sexual overtones. This was the period at the company that gave the world Identity Crisis, after all.

And, oh, you want to know what else happens in War Games? Sure, Stephanie Brown, pretty, blonde, white girl, gets killed in a bad way. Orpheus? Killed off-panel, between issues. We catch up with him after he’s dead, also murdered by Black Mask, who strips the corpse so he can impersonate the hero. That’s it: the best aspirations in the world, killed for a cheap jump scare at the end of an issue of Catwoman. Dwayne Turner had nothing to do with War Games, I hasten to add. Lots of people did: Ed Brubaker, of all people, wrote the issue of Catwoman where Orpheus’ murder is revealed, drawn by Paul Gulacy. The issue of Batman where we get our last shot of Orpheus, stripped naked and humiliated, was written by Bill Willingham and drawn by Kinsun. It’s fair to say that none of these gentlemen had full say in any of the events of War Games, a story also co-written by the likes of Greg Rucka, Devin Grayson, and Dylan Horrocks. No one comes off well here, there’s blame to go around.

But as I say, Dwayne Turner was nowhere near that mess. No, he was across the hallway in another mess of equal and opposite magnitude: the ongoing slow implosion of Wildstorm from the moment of the DC acquisition. They tried like hell to make that imprint a thing. This was the era of Joe Casey and Ashley Wood’s Automatic Kafka, Casey’s WildCats with Justin Nguyen, the first stirrings of the Ed Brubaker / Sean Philips dyad in Sleeper. And then over to the side they were doing what would in hindsight turn out to be the umpteenth Authority revival.

The funny thing about The Authority? The actual Warren Ellis / Brian Hitch Authority that set the course for the next decade at both Big 2 companies, for better and for worse and in so many ways, that book lasted a year. That’s it. No one wanted anything else from those characters. We know that, manifestly, because they have spent the succeeding century trying to convince us that we did, and failed. Tom King is doing The Authority literally as I write these words, no one cares. Good creators and bad have been thrown at the problem. Dwayne Turner was drawing Volume 2 of The Authority, with Robbie Morrison writing. He did that for a year, from the Summer of 2003 to the Summer of 2004. I wish I could tell you it wasn’t manifestly a cursed chalice assignment for both of the primaries. They were, to be fair, taking over for the previously announced creative team of Brian Azzarello, Steve Dillon, and Glen Fabry. Supposedly 9/11 scuppered that launch. Turner’s work on the book is, frankly, desultory. I won’t belabor the point because I can’t imagine a universe where this comic could have been better, given the circumstances. It lasts a quiet year and is put to bed. The covers were still strong, but you can plainly see his heart wasn’t in it.

And then, after a year of dragging that line, he’s out. Never works in comics again.

That’s a real bummer of a note to end a story on. Took a while to write this article partly because there isn’t a happy ending, as far as that goes. His career in comics just kind of sputters out. I don’t recall there was a retirement announcement, but I don’t recall anyone was paying attention to Dwayne Turner in 2004. And that was the problem.

Dwayne Turner’s career in comics, for better and for worse, is a testament to a love of comics. Superheroes as a genre, comics as a medium, artist as a profession. He did everything the right way. He went to a great school. He had talent. He specifically chose to emphasize work with black characters, with a deep and abiding affection for enduringly popular mainstays Black Panther and Luke Cage. He worked with good people, go down that list: Roger Stern, Dwayne McDuffie, Don McGregor, Larry Hama, Chris Claremont, Todd McFarlane, Paul Jenkins. Enviable list of collaborators for any artist of any generation. Drew Wolverine, Batman, and Spawn. Drew the first ever ongoing Spawn spin-off.

His Curse of Spawn should be beloved by the kind of sickos who revere Vigil & Quinn’s Faust, but I don’t get the feeling it’s particularly well remembered. It was the first ongoing Spawn spinoff but most definitely not the last, so it blends in. Everybody already knows Todd gets good artists to draw stuff that not everyone loves.

And yet, despite all that, Dwayne Turner is out by 2004. We didn’t appreciate what we had when we had it.

But, as I said above: this is where the happy ending happens. Because, just on paper, it’s a very happy ending for Turner. It’s a shit ending for the comics industry, but a familiar shit ending. Comics loses talent to Hollywood all the time. It’s never a bad thing when it happens because it always means the creator involved is getting paid more money, and that should always be the primary goal of every freelancer at all times. It’s hard to make a living in this world as an artist.

This is where I switch websites. I depend on the good folks at comics dot org for the work they do in maintaining that database. It’s a remarkable tool to which these articles owe their existence. But their record of Dwayne Turner ends more of less at the reelection of George W. Bush. After that, his career picks up on IMDB. First work he does outside the comics industry, at least as listed on his IMDB page, is concept work for the Def Jam Vendetta video game in 2003, which I believe is still beloved among its devotees. He does storyboards and concept work for the first two God of War games, (2005, 2007). He leaps to Hollywood proper a couple years after that, first in Tron: Legacy (2010) - storyboards - and from there consistently for the next decade and a half. The Tron sequel leaves a bigger cultural mark than its meager box office implies, par for the course for the franchise. He did storyboard for two Alvin & the Chipmunks movies - not the Squeakquel, alas, but Chipwrecked (2011) and The Road Chip (2015) both of which made an enormous amount of money by any measure. He does storyboard work on a handful of those otherwise noxious live action Disney remakes - Jon Favreau’s not completely witless Jungle Book (2016), and that same year the generally regrettable Alice Through the Looking Glass.

Successful movies and flops, it’s consistent work in a town where that hasn’t necessarily gotten easier in the last decade. He worked on X-Men: Dark Phoenix and Morbius, as well as a few movies which I would have sworn were fake but were apparently only released to streaming. They did a Lady & the Tramp remake in 2019. He also worked on the underrated Alita: Battle Angel, which not a lot of people saw but which was a much better movie than you could have anticipated based on the tortured development history.

Hollywood treated Dwayne Turner a lot better than comics. The proof is right there in black & white: he has worked steadily and consistently as a storyboard artist in the upper echelons of big-budget filmmaking. He’s done Spider-Man and Santa Claus. Good or bad, you’ve seen his work if you’ve watched movies in the last two decades. You just haven’t seen his hand in what he’s done. Those movies all involve thousands of people. He’s one of those thousands. Nice work if you can get it. I understand it’s not always an easy business to be a part of right now, but they’re still doing better than comics.

Anyway. Dwayne Turner. A career strangely before its time. Made all the wrong right decisions, which is just how it works sometimes. He deserved more from comics. I’m glad he got it somewhere. I wish Dwayne Turner had drawn more comics, but I don’t think he does. More power to him.

The post Murderers’ Row – Dwayne Turner appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment