Richard Sala was comics’ most reliable artist of criminal masterminds and colorful lowlifes; of mystical mediums and femme fatales. Informed by surrealism and monster movies, his work landed somewhere between the garage-camp of the Cramps and the more sober otherworld-building of Thomas Ligotti. Sala brought an ironic touch to pulp iconography without ever condescending to it. That feat would be enough to distinguish another artist, but he was also remarkably consistent, with each new work as satisfying as it was familiar. And as this year’s new printing of Night Drive confirms, he arrived remarkably well formed.

Sala self-published the first edition of Night Drive, his debut as a cartoonist, in 1984. He kept the collection of short works out of print for decades afterward. Daniel Clowes, in his afterword to Fantagraphics’ rerelease, notes Sala “grew more and more dismissive” of these early pieces. This new edition follows, and addresses, Sala’s death in 2020, adding “outtakes” from a scrapped follow-up to the original Night Drive and celebrations of Sala from Clowes (the book's designer) and writer Dana Marie Andra (its editor). Their contributions are moving; the result is also vexing. Issues most proofreaders would catch (inconsistent italics, missing or unnecessary commas, etc.) mar front- and backmatter passages praising Sala’s talent and spirit. Final fault here lies with the publishers. These are avoidable mistakes, and a book memorializing a master cartoonist deserves a better system of review.

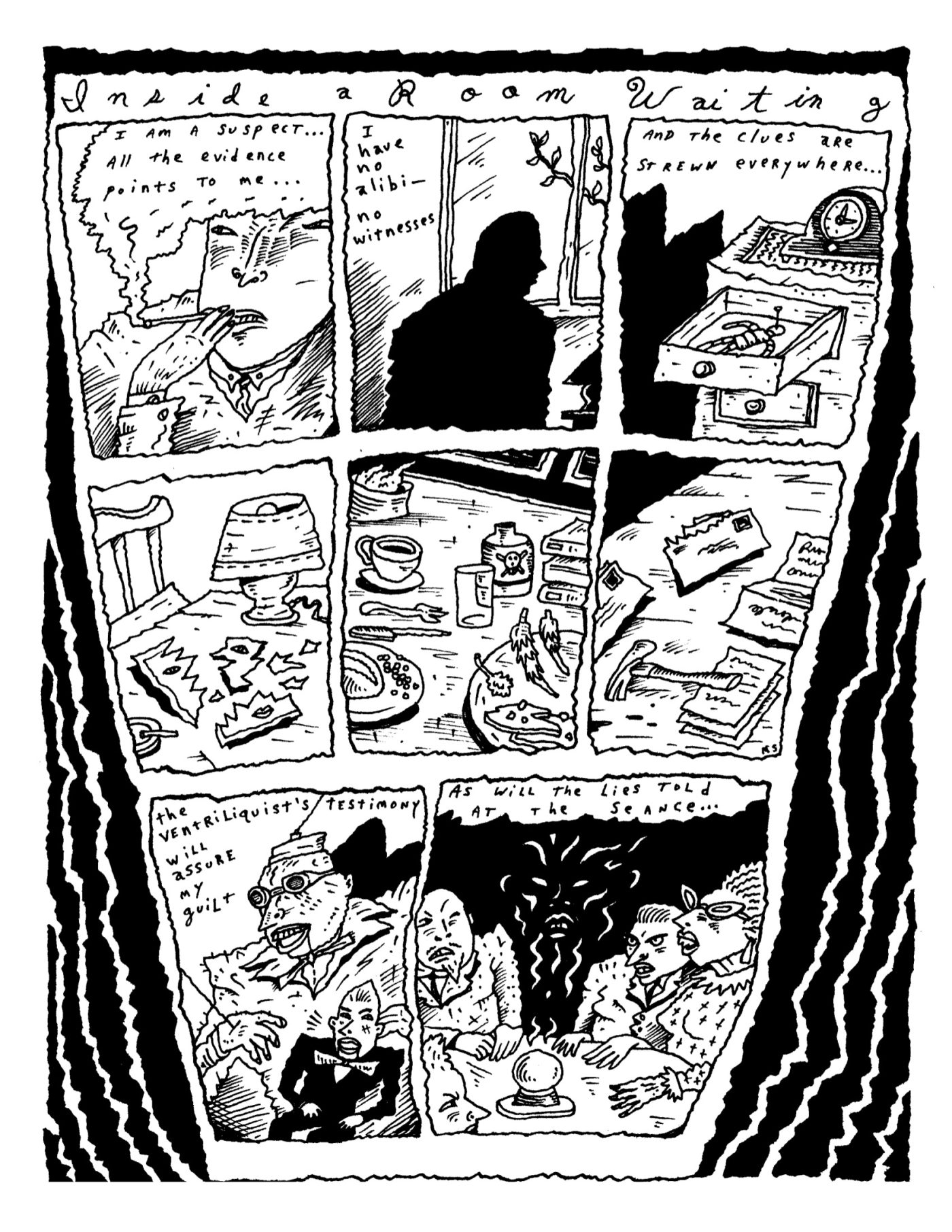

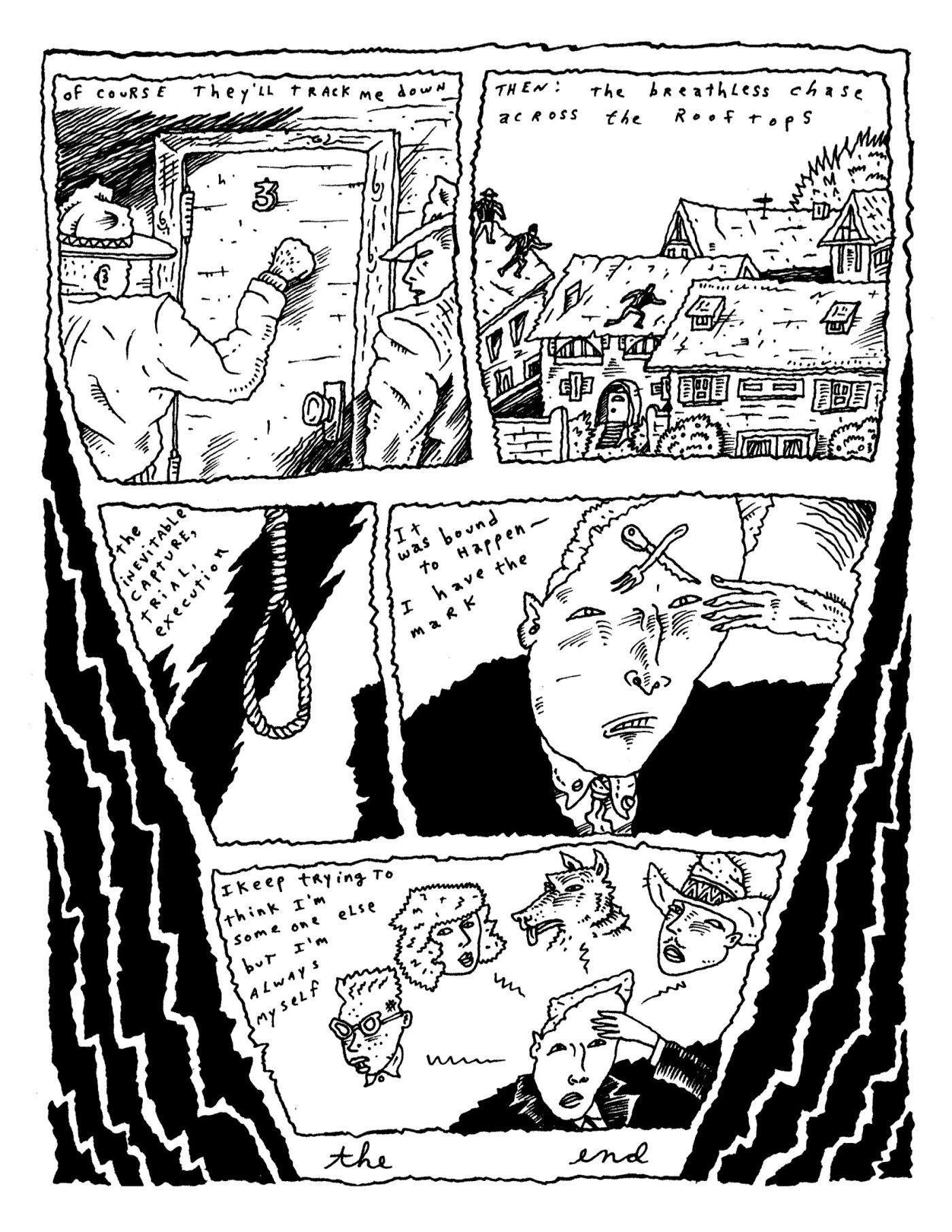

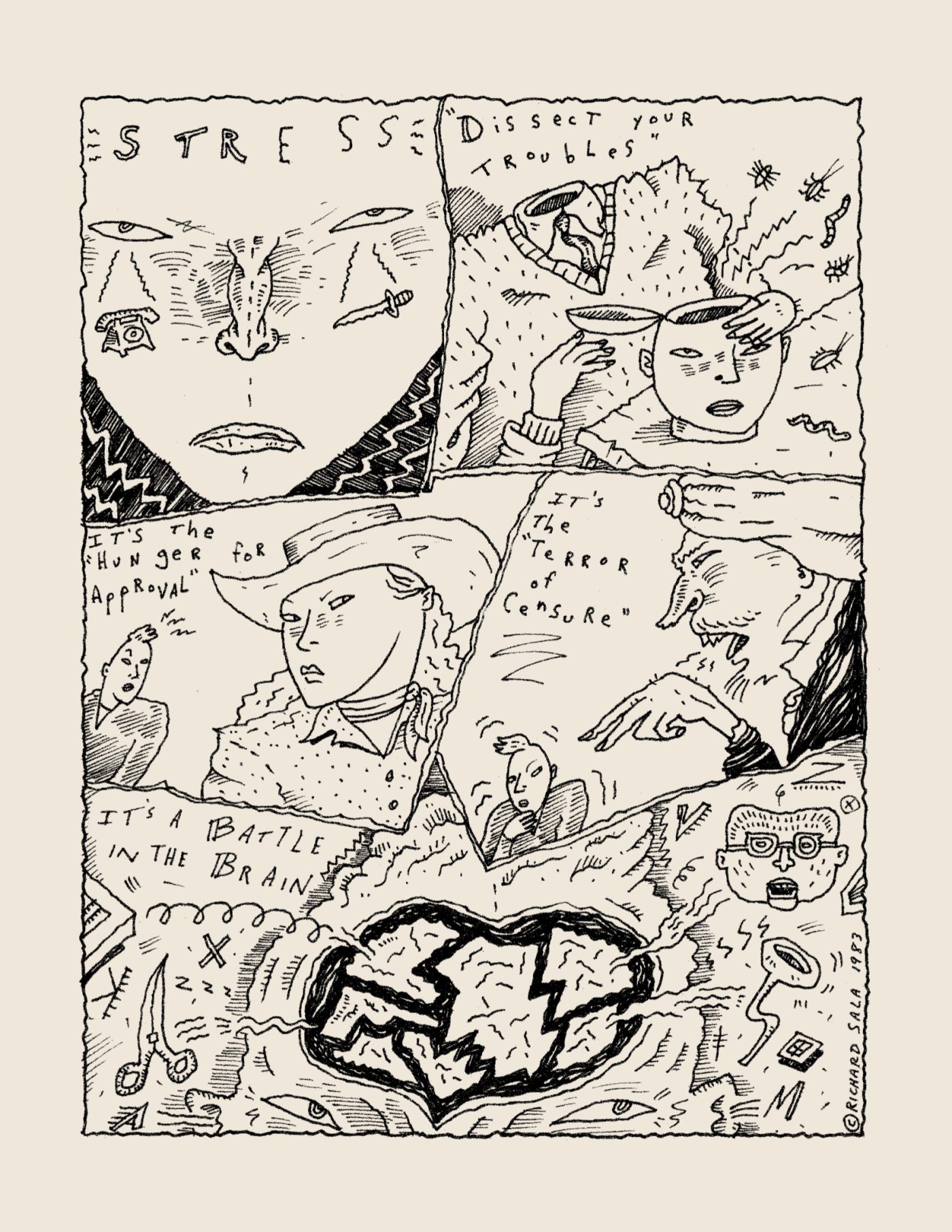

More notable, however, is the level of continuity — in linework, motifs, tone — between the pieces in this collection and Sala’s later works. Advancements after Night Drive would be matters of degree. Sala’s line, for example, is unmistakably that of the man who made The Chuckling Whatsit. It trembles, as if Sala’s depicting not only the details of scenes but their frequencies; readers see dark alleyways and thatched roofs rendered with a vibrational instability. In Night Drive’s earliest pieces, “Curiosity,” “Possession,” and “Inside a Room Waiting,” pages work like seismographs of evil intention, with Sala’s pen the needle.

Night Drive also offers a look at what was different in Sala’s earliest comics. Over time, he stretched out into long-form narratives, serializing and then collecting them. Night Drive’s pieces are shorter (many of them one or two pages) and often feature less narrative altogether. Sala came to cartooning after a fine-arts education, but the comics in Night Drive read less like gallery pieces and more like poems. One, “Little Apocalypse,” offers readers a path through the page but not a sequence per se. Instead, Sala arranges a small set of evocative phrases and images, the piece achieving its impacts through atmosphere and suggestion.

Exceptions to this poetic mode, pieces that most resemble Sala’s later works, include “Invisible Hands,” later adapted for MTV’s Liquid Television. Here, in a comic where Sala does privilege plot — in a story of setups, revenge, and psychic messages — a reader sees him gathering almost all the qualities he’d use steadily across his career. But even Night Drive’s more orthodox pieces omit one element Sala later embraced: sexuality.

Sala shows readers sex through a glass nostalgically. When his comics foreground it, they tend to suggest a formative encounter with a ’60s pinup calendar or beach-party movie. It’s nevertheless one of the most overt threads of his career. Intrepid beauties are central to Sala stories such as The Bloody Cardinal and “Cave Girls of the Lost World” (Poison Flowers & Pandemonium), chasing clues or swinging daggers with the same verve as his other characters. There’s a manneredness to these depictions — or, less charitably, a status as object the characters maintain despite their plot-level agency. Sala’s women often resemble paper dolls, more so than other on-page elements. Urge and artifice are both evident, with figures of desire reading like representations of representations of representations. This negotiation plays out frequently in his later work, but it’s scant in Night Drive.

Along with the absence of what came later, Night Drive gives readers a glimpse of what might have been. If there’s one quality a reader finds more of in Night Drive’s early pieces, it’s a relatively direct depiction of psychological distress. The condition of Sala’s mental health — he was “crippled by terrible anxiety and profoundly agoraphobic,” per an earlier memorial from Clowes — seems to find expression throughout Night Drive, especially in the outtakes section. These moments are heightened (it’s still Sala), but the membrane is thin.

“Unhealthy Preoccupation” shows readers a figure who’s “a little in the dark [...] with fire on the mind,” scrawling on paper to make his thoughts legible. “Stress” visualizes a fragmented mind, divided like a map, and mentions “a battle in the brain.” The narrator of “Living Under the Volcano” admits an “inappropriate response” and “inappropriate desire,” while an ominous shadow-self creeps into the final panel. And multiple pieces depict the contents of their narrators’ bad dreams. A reader can’t take these comics as straight memoir any more than they can pieces about detectives or were-dogs. Even so, the expanded Night Drive suggests a reading of Sala’s trajectory from ’84 onward, with the artist receding from early efforts to make his pain legible and diving further into escapist fantasy.

Except, such things are rarely that simple. Night Drive’s outtakes may fuel speculation that later stories were safer havens. But to the extent the details of Sala’s life feel relevant to readings of his work, they lead to more mystery too.

Perhaps Sala scaled back the level of personal detail on his pages, avoiding the discomfort that came with confronting it. Or perhaps that’s all wrong, and he realized instead that the tools for a truer (if less obvious) portrait of his interiority were with him already, finding the density of symbol he needed within genre. Perhaps it’s even simpler than that, and Sala’s linework proved a better register of anxiety than comics that made it their subject; and with distress as a topic made redundant, he was free to draw costumed assassins. The rerelease of Night Drive doesn’t lead readers to answers, only to questions, but questions are the best part of most mysteries anyway. Returning to later stories, a reader does not find them fully illuminated, but may feel more attuned to their frequencies, or hear echoes sound more deeply down Sala’s dark corridors.

The post Night Drive appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment