In my humble opinion, the Tsuge brothers deserve a spot on the Japanese gekiga podium — perhaps even one each — alongside Tatsumi Yoshihiro. It’s hard to choose: Do I revere Yoshiharu for his raw and introspective The Man Without Talent, or for the surreal and seminal explorations of Nejishiki? Or do I admire Tadao more for his compelling depiction of Japanese lowlife society in his short stories? To tell the truth, I don’t really need to choose.

But if readers appreciate The Man Without Talent — a poignant meditation on life seen through the disillusioned and weary eyes of middle age, laden with disenchantment — they shouldn't miss another masterpiece coming from the same household: Tadao’s Boat Life.

While The Man Without Talent was created in the early 1980s, Boat Life took shape a little later, spanning the ’80s and ’90s. At the time, Tsuge Tadao — born in 1941, four years younger than Yoshiharu — had already built a long and relevant, albeit not very successful (by manga industry standards) career in comics. He was also running a jeans shop, now managed by his son. I first learned about this shop in Viaggio a Tokyo (Voyage to Tokyo) by Italian cartoonist Vincenzo Filosa — an excellent read, if you can find a copy of the Italian edition, which includes an English translation (the book is also available in French from Lézard Noir).

Boat Life begins by showing us an elderly man teetering on the edge of depression. The protagonist isn’t explicitly Tsuge Tadao himself, but rather a fictional persona through which the author channels his experiences and emotions. Yet, at its core, the character is clearly a stand-in for the author.

Tsuda is a writer who has never achieved any real success and struggles to get his work published. At the same time, he manages the family clothing shop, much like Tsuge himself. We see him worn down by the monotony of daily life, exhausted by existence itself, with only one true passion, fishing. He spends long hours along the riverbank, casting his line, taking slow walks, observing other fishermen, and engaging in lengthy conversations with them.

Beyond that, he has little interest in the world around him. He feels detached from everything and everyone, especially his own family. He withdraws, spending as much time as possible fishing alone. The river becomes his refuge, a sanctuary he desperately needs. When he stumbles upon an old, rundown fishing boat on the Tama River (one of Japan’s major rivers, flowing through Tokyo), he seizes the opportunity and buys it. Presenting the idea to his family, he claims he simply needs solitude to focus on his writing. In reality, Tsuda’s true plan is just to spend as much time as possible alone on the boat—essentially making it his home along the riverbanks.

Unsurprisingly, his family does not take the choice too well, but he seems indifferent to their concerns.

"Don’t be ridiculous! You can’t live on a boat!"

"I don’t mean permanently. Just three days a month or something ..."

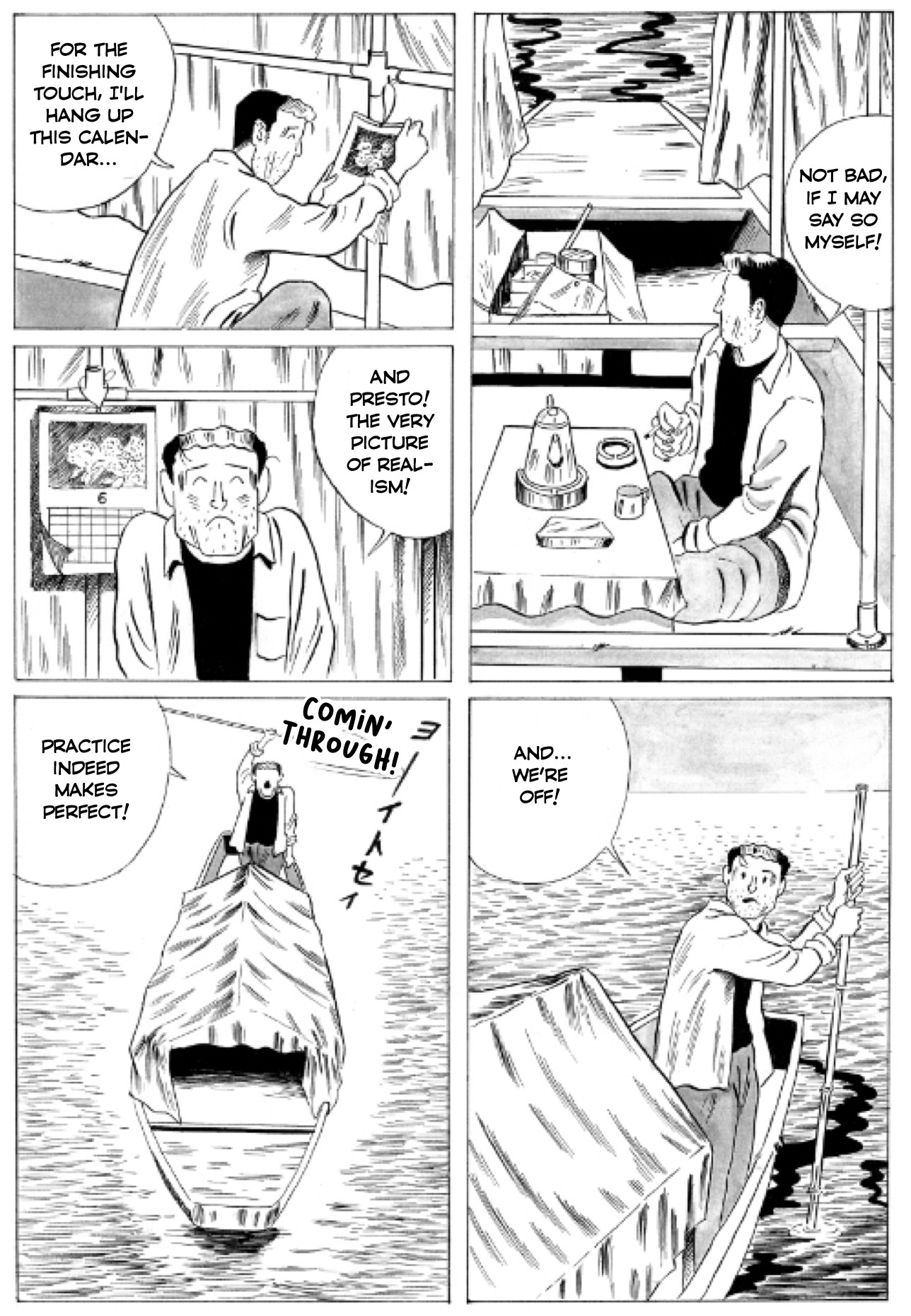

Determined, he sets about restoring the rickety wooden boat bought from an old man, though even after repairs, it still looks like a wreck. Over time, his brief escapes stretch into longer and longer stays, until his days aboard the boat turn into extended, solitary retreats along the river.

"By the way, chief, that boat of yours sure is ugly!" a fisherman remarks. "I renovated it myself," Tsuda replies, his head lowering slightly as we see him from behind, shoulders slumped in quiet resignation.

That small, abased gesture speaks loudly about Tsuda — and about the way Tsuge Tadao tells his story. His late-career commitment to faithfully capturing reality is something rare and hard to come by. His approach is even more grounded and neutral than that of his brother's, whose stories — no matter how stark, even in The Man Without Talent — are often infused with a lingering sense of wonder, a bleak yet undeniable magic realism.

Both brothers boldly dedicated themselves to telling stories no one else dared to, not because these stories were too controversial or extreme, but because they were too ordinary, too deeply rooted in the lives of forgotten people, whose stories don’t sell. If The Man Without Talent is a cynical meditation on the profound despair of middle age, Boat Life pushes further, exploring the quiet discontent of an ordinary, aging man. After all, who wants to read a graphic novel about that?

Tsuda is even more unremarkable than the protagonist of The Man Without Talent. He possesses no particular quality, he is a grandpa or an uncle like any other. Yes, he’s a writer, a respectable family man, but is that enough? Will it ever be? He knows the answer, both for himself and for those around him. So, at an age when most people resign themselves to the status quo, he makes an unconventional choice. His retreat to the river is an act of defiance, and narratively, it takes Tsuge into uncharted territory.

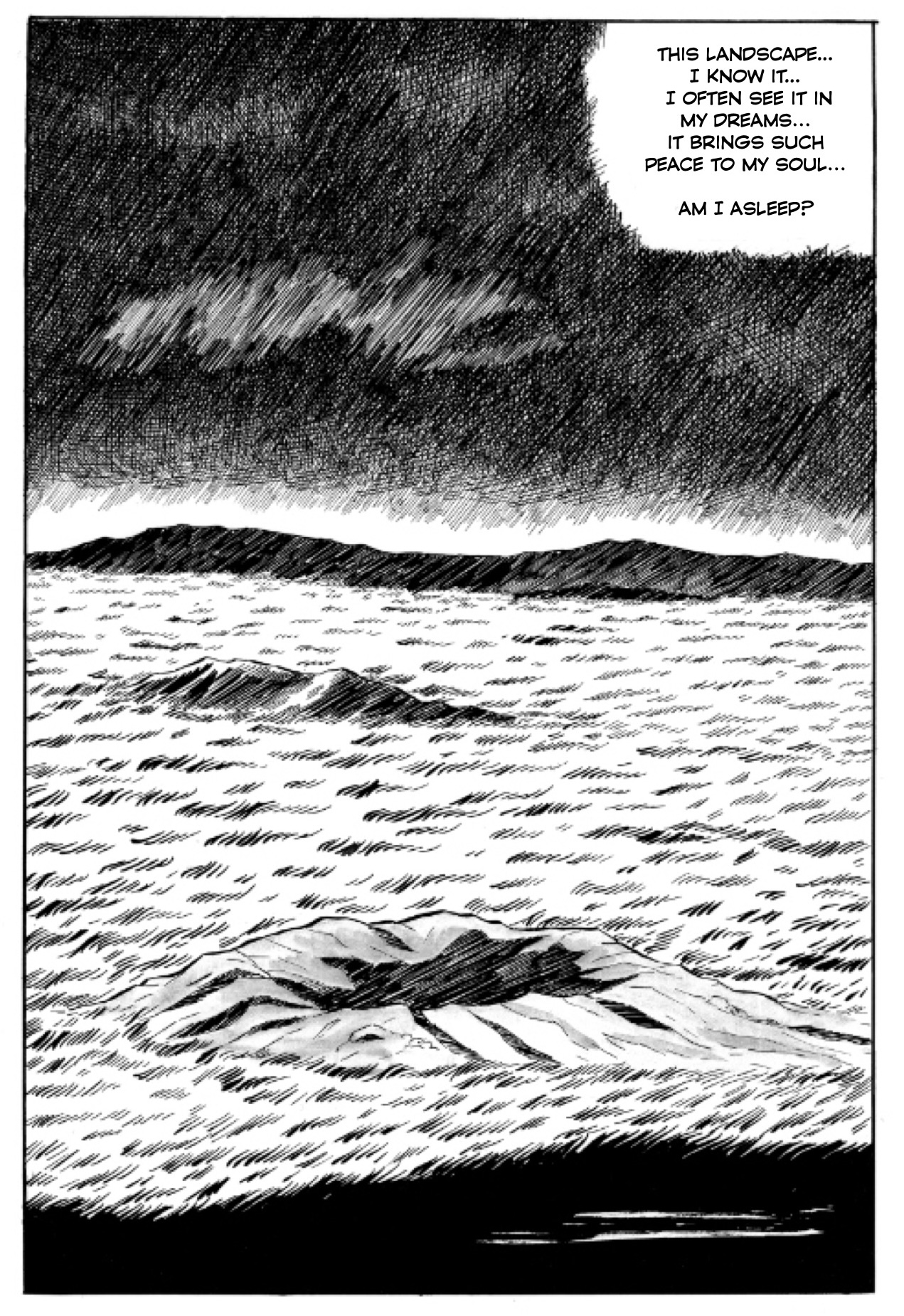

The river, so open and wide, offers both freedom and hopelessness to the story. It can be seen as a narrative agent that brings along many possible metaphors, and even a supernatural character, alongside the battered Tsuda.

What could possibly happen to a man in poor health, living on a boat in poor condition? The river carries him into a world where reality slowly loses its clear edges, and dissolves into surreal, dreamlike sequences. Early in his new life, Tsuda falls ill aboard his makeshift home, in a long moment that doesn't just predict failure for his attempted escape, but shows also his refusal to surrender to it. Boat Life is more than a story about aging. It is also a quiet, reflective challenge to the conventions of travel literature, addressing movement not as an adventure, but as a still, introspective journey.

Boat Life is a mature and elaborate exploration of the “watakushi manga” (the “I-novel”, characterized by self-revealing narration), one of the most delicate kinds, troubled yet still softly meditative. With it’s black and white lines so thin and accurate, and scenarios full of details, Tsuge creates a story where reality and dream are separated only by something light and impalpable, like a thin veil of mist on the banks of a river.

The post Boat Life Vol. 1 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment