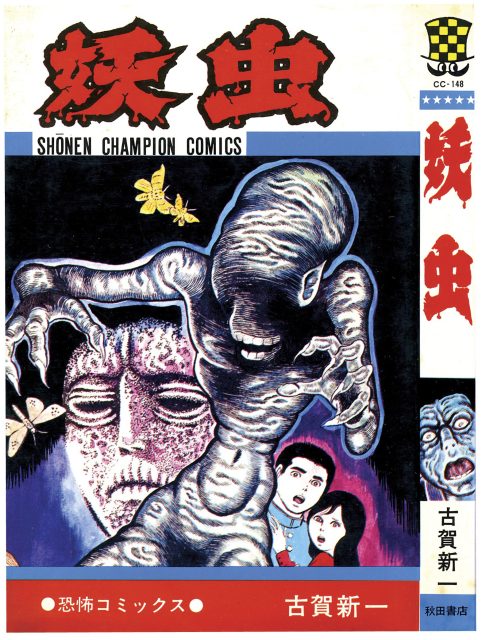

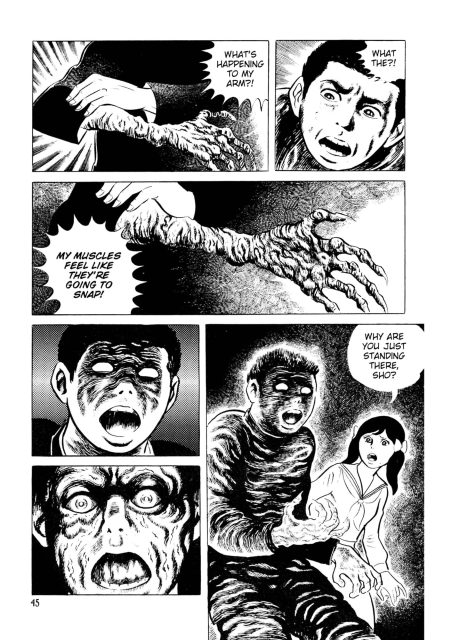

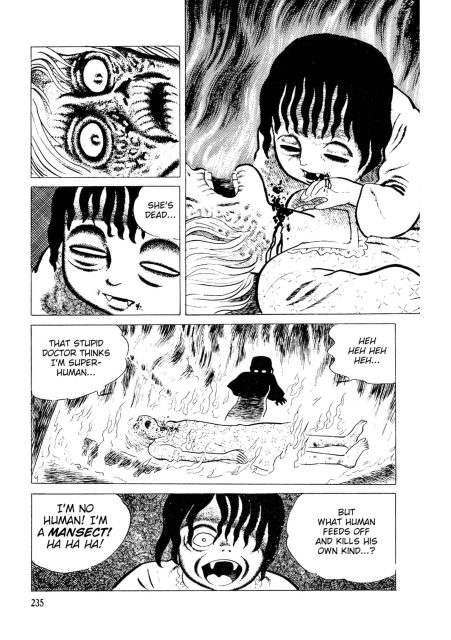

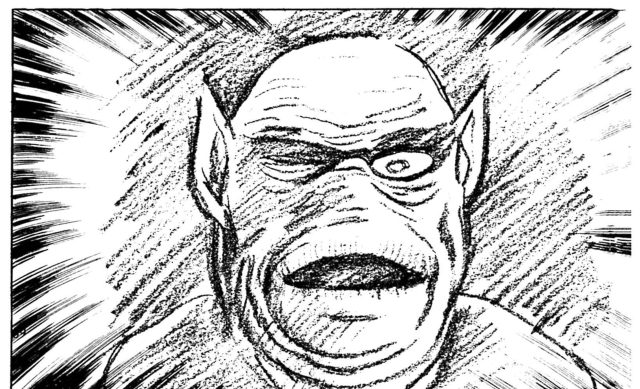

The freakout begins on the cover: the title’s B-movie economy and urgency is emphasized by fat, crackly lettering, and the monster is right there in lurid red, limping its way through a glitchy RGB landscape in a punchy contemporary treatment that maintains some of the feel of the cover of Shōnen Champion Comics in which Mansect was originally serialized in the 1970s. The drawings inside are high contrast with large expanses of deep inky black, reminiscent of Umezu’s Cat-Eyed Boy and some of Mat Brinkman’s gnarlier post-Multi-Force work. The story opens with the protagonist Hideo holding a butterfly net and trudging between two rock formations, circled ominously by crows; artist/writer Koga Shinichi manages to give him a desperate, haunted look with just a few pen strokes. Still grieving the loss of his mother, Hideo has turned an interest in entomology into an obsession. His house is filled with insects and he’s become a subject of gossip among his fellow villagers as well as bullying from local kids, who trick him into stepping into a pool of manure, thereby triggering his metamorphosis into the title creature. The story subsequently pulses and oozes from one horror to the next as sad young men transform into abject monsters while, from the sidelines, heartless mothers scold and ineffectual scientists pontificate.

Mansect is the third release from Smudge, an imprint of Living the Line Books specializing in new English editions of vintage horror manga, following last year’s Her Frankenstein and UFO Mushroom Invasion. Like its predecessors, Mansect features a translation by the prolific Ryan Holmberg and design by Living the Line impresario Sean Michael Robinson, and the result is an unsurprisingly sensitive, high-quality production. It feels pulpier than the others—literally as far as the paper is concerned (perhaps the result of a change of printers), but also due to the absence of a scholarly essay of the kind found in the previous titles, as well as the highest rate of freaky what-am-I-even-seeing drawings and unnerving story occurrences per page.

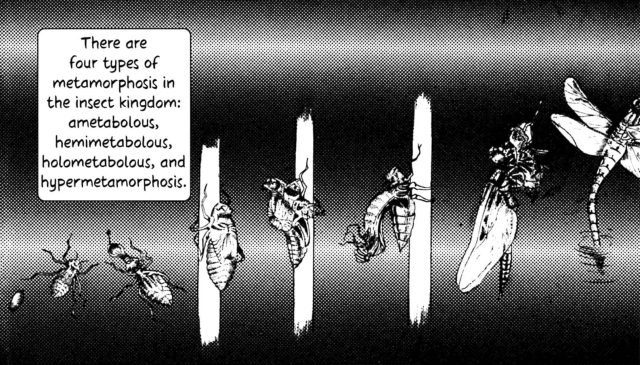

The common manga trope of varying levels of verisimilitude, toggling between cartoon stylization and realism (sometimes on the same page) in the drawing is used to good effect, giving emotional specificity and weight to certain moments while still moving the story along briskly. The detail found in character’s faces varies dramatically according to psychological or emotional needs in the story, while loving attention is lavished on spooky tree limbs, damp cave walls, and heavily textured monster bodies. Although Mansect is, of course, no Moby Dick, the particularly crisp illustrations of insects on a page like 14—similar to those you might find in a textbook or visual dictionary—put me in mind of the chapters on cetology woven through Melville’s magnum opus, serving a similar purpose of simultaneously edifying while also underscoring the impotence of understanding before ultimately inexplicable horror. Broadly speaking, Mansect has the best drawing of any of the Smudge releases so far—the draftsmanship in Her Frankenstein is slick and accomplished but more generic, and that of UFO Mushroom Invasion is charming and occasionally brilliant but lacks the range or frequency of impact found in that of Mansect.

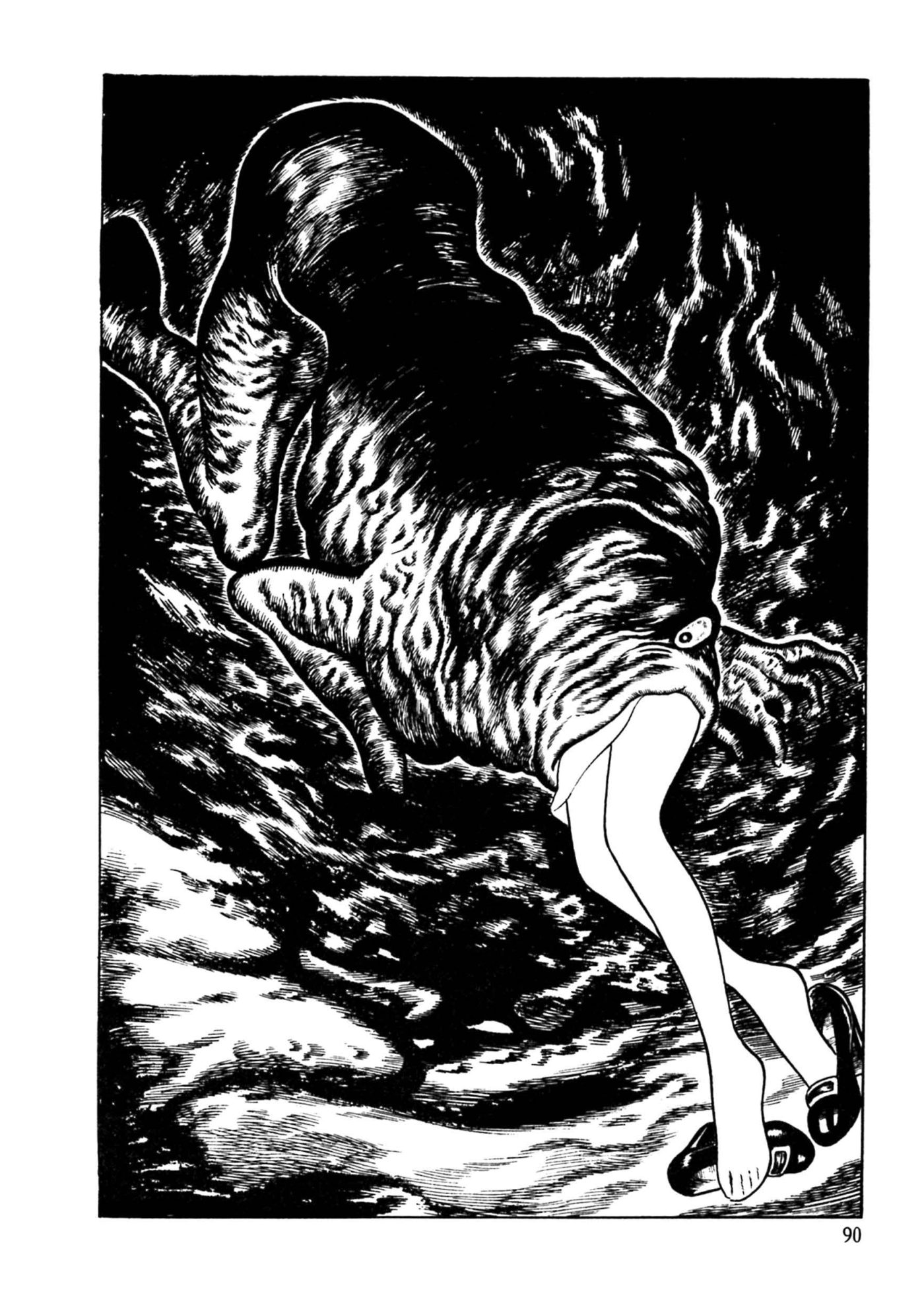

The page structure is relatively simple and sober, a counterpoint to the hysteria of much of the imagery. Koga deploys one to nine panels per page and only vertical and horizontal gutters, eschewing the diagonals that appear frequently in postwar manga. The most striking layout motif is the frequent and evocative use of bleeds, which here pour into the margins and away from the spatio-temporal structure of the other panels to evoke experiences so terrifying that they break conventional boundaries of time and memory. The many metamorphoses throughout the story often literalize the body keeping the score of trauma, and the bleeds serve a similar function on the page.

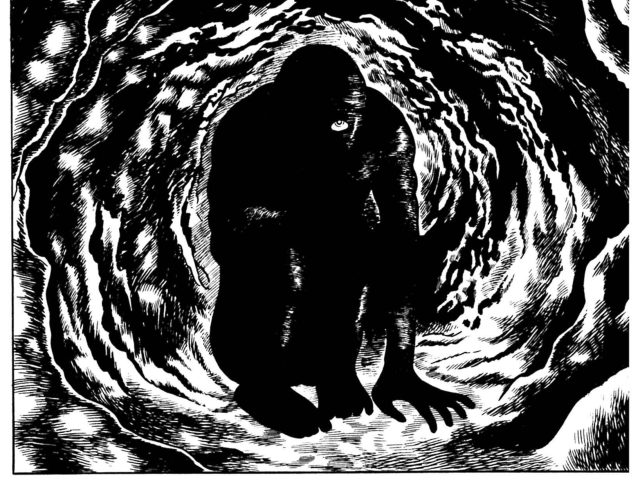

Grotesquerie is an obvious feature of the imagery of Mansect, but it operates in the story in ways that may not be immediately evident. Etymologically linked to the grotto and first used to refer to fantastical decorative painting unearthed in the excavation of Nero’s palace in the 15th century, the grotesque may be best understood as a category of aesthetic experience in which two opposing elements are held together in irresolvable tension. The classic grotesque dyad is attraction and repulsion, and Mansect is shot through with the queasy pleasures of many drawings in which we can appreciate the beauty of the artist’s use of line or texture to articulate a repulsive form. In the 19th century John Ruskin posited that the two elements that make up the grotesque are ridiculousness and fearfulness1, and this is a tension we experience anytime we encounter an image that’s jarring as much for its absurdity as its horror—for instance the bravura splash page in which the title monster (barely distinguishable from its subterranean surroundings by virtue of a white outline and a single cartoony eye) is shown with a woman’s legs dangling from its mouth which, along with the contours of her skirt, make a visual pun on labia while the mules dangling from her feet are drawn in a contextually unbearable deadpan. It’s all just too much, in every sense of the term.

The grotesquerie of Mansect operates not just at a visual level but a conceptual one as well. In the 1980s, humanities professor Geoffrey Galt Harpham articulated a theory that when the metaphorical and the literal are confused or one begins to give way to the other, the effect is frequently grotesque2. This theory can help illuminate the relationship of Mansect to Tezuka Osamu’s Book of Human Insects, published just a few years earlier. Where Tezuka—himself an enthusiastic amateur entomologist—deploys insect metaphors to underscore his female lead Toshiko’s sociopathic predation, deception, and especially her ruthless social climbing (which Mary A. Knighton persuasively suggests was a way for Tezuka to spin a kind of feminist story out of sexist tropes3), Koga’s traumatized beta males literally embody their abject outcast status by becoming repulsive, dangerous insect hybrids. Moreover, while Toshiko participates in ritual self-infantilization with a wax mother figure, Hideo’s mommy issues culminate in a final metamorphosis into an actual infant bearing an uncanny resemblance to Hino Hideshi’s Hell Baby.

Though the term otaku was not widely used in its current meaning until the 1980’s, Hideo may be considered a kind of proto-otaku—a socially marginalized nerd with an obsessive hobby and an unseemly interest in young girls. Outside its use as slang, otaku literally means “your house.” Hideo’s monstrousness begins in the home, the site of tragic family circumstances of traumatic loss and grief. The Freudian tropes that run through the story can be seen through this lens as well, since Freud’s essay on the uncanny (itself a species of the grotesque) includes an etymological exploration that could be a thematic map of Mansect, including meanings of heimlich: “belonging to the house [like otaku] or family, the taming of wild animals [like the bugs Hideo befriends], a state of being concealed and kept from sight; and unheimlich: uneasy, eerie, bloodcurdling, ‘the name for everything that ought to have remained . . . hidden and secret and has become visible’”(italics Freud’s). Hideo’s relationship to Akiko and Yumi—both young girls—can be seen as an early example of lolicon (or “Lolita complex”) in manga, which would become increasingly common in strands of otaku culture by the 1980’s. The allusion to Lolita is most explicit the way Yumi reminds Hideo of a girl he knew in fifth grade, just as Lolita resembles Humbert’s lost childhood love Annabelle Leigh—a name that is itself an allusion to a poem of young love and death by Edgar Allan Poe.

Manga of the postwar period was famously influenced by cinema, and classic Universal Pictures monsters show up throughout Mansect: Akiko’s drawing of Hideo resembles the Creature from the Black Lagoon; another monster in the story looks like a cross between Lon Chaney’s Phantom and Carolee Schneeman’s Eye Body #20; and Hideo’s final form has a blocky head and stringy black hair like Karloff’s Frankenstein’s monster. Mansect seems to presciently prefigure future horror films as well: the monster sometimes resembles a lumpy xenomorph from the Alien franchise; in other drawings it’s a dead ringer for Cronenberg’s Brundlefly. There are also premonitions of Dario Argento’s giallo film Phenomena, which features a bullied student with the ability to summon insects and a deviant, grotesque child-monster.

After much often upsetting and sometimes confusing mayhem, Mansect ends on a pseudoscientific, quasi-philosophical note about diseases and evolution reminiscent of the speculations in UFO Mushroom Invasion—but this isn’t science fiction, and the insect theme ultimately gives way to one of seemingly supernatural metamorphosis more broadly, and infantile regression more specifically. The story often feels like an engine for getting from one lavishly grotesque drawing to the next, but we are compensated with some truly indelible images. They remain the most enjoyable parts of the book, and it’s to Koga’s credit that the enjoyment is almost always adulterated with a dose of dismay or disgust. Its thrills and jolts may have an adolescent appeal, but the story is also about how those who are unwilling or unable to grow up—even as a result of their own very real psychic wounds—can do great harm to those around them. Mansect barely passes the Bechdel test (two women briefly discuss one of their daughters) but it’s unlikely to celebrated in the Manosphere either. It’s all too easy to imagine several panels from the book becoming “Men will literally _______ than go to to therapy” memes where “become an abject insect monster living in a cave” fills in the blank.

The post Mansect appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment