Harold Schechter and Eric Powell’s graphic biography of Dr. Fredric Wertham — the great bogeyman of comic book history — is sympathetically (and beautifully) illustrated and includes sincere attempts to highlight some positive aspects of his life. Because of this, readers may not realize how far Dr. Werthless falls short in doing justice to his memory. More than Wertham’s personal reputation is at stake here, though.

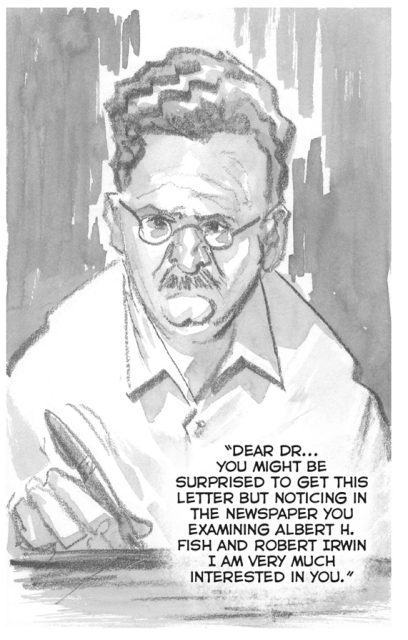

Schechter and Powell, both fans of true crime stories, began this project after previously collaborating on a graphic novel about serial killer Ed Gein. They were drawn to the subject of Wertham, partly because, as a psychiatrist, he had treated and then written about two of the craziest murderers of the 20th century. Schechter had already authored books about them: The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, the Model, and the Murder that Shook the Nation, about Robert Irwin, and Deranged: The Shocking True Story of America's Most Fiendish Killer!, about Albert Fish.

Wertham also had been the most important figure in the anti-comic book movement, which had pushed violent horror comics off the newsstands in the 1950s. Co-author Eric Powell brings his own relevant background to the book as the creator of the excellent, long-running, violent comedy/horror comic book series The Goon.

In this work, Schechter and Powell have woven together Wertham’s life story, including his campaign against comic books, with many pages detailing the notorious crimes of some of his patients.

Their story immediately gets off on the wrong foot. Without naming Wertham, they falsely suggest that he believed “if young people could only be shielded from violence in media, juvenile crime would cease to exist.”

Schechter and Powell unfairly depict Fredric Wertham as an angry, difficult person who could not fit in, get along with others, adapt, compromise, or admit when he was wrong. They suggest that because of his stubborn and unlikable nature, Wertham missed out on career opportunities and spent his life feeling frustrated.

Actually, the issue of fitting in was one of Wertham’s important concerns, but he wrote about it as something that he purposely opposed. Wertham championed a radical approach he called “social psychiatry,” and vigorously criticized psychiatrists who thought their job was to help their patients become well-adjusted to things as they are.

Dr. Werthless includes two anecdotes about Wertham’s early experiences in Munich, Germany, but fails to grasp the significance of these stories. By omitting the political lessons Wertham learned, this graphic biography loses the core of his message.

In one example, the authors present “differences” between Wertham and his first mentor, the founder of biological psychology Emil Kraepelin, over the case of a young man who had killed an old man for his gold watch. We see Kraepelin call the man a “common murderer” with no biological abnormalities while Wertham explains that “this murder took place in Germany after the war, a time of poverty, unemployment, unrest, and bloody political struggle.” This makes it sound as though Wertham was merely arguing that harmful environmental influences contribute to violence.

Schechter and Powell miss the different, stronger point that Wertham was trying to make. When Wertham told this story in his 1949 book The Show of Violence, he noted that a professor of psychiatry who was present during this argument and shared Kraepelin’s views went on to develop “the ‘scientific’ rationalizations” for killing some 275,000 mental patients.

In a later book, Wertham expressed his belief that understanding violence requires studying how leading German psychiatrists, working in the best public psychiatric hospitals in the world, became directly responsible for mass murdering their patients. He asks us to consider not just the individual psychology of a young man who killed for a gold watch, but also the psychology of the normal, respectable people who organized a holocaust so skillfully that it ran like clockwork.

Of the various stories in Dr. Werthless that illustrate Wertham’s uncooperative nature, the one that might at first seem most convincing involves another of his experiences at that same prestigious German Research Institute of Psychiatry in Munich, where he returned in 1930 to conduct research for his book The Brain as an Organ. Schechter and Powell quote letters from the Institute’s director, Walther Spielmeyer, in which Spielmeyer states, “I find Wertham unreliable and untrustworthy. … what troubles me most is the way he exploits the lab assistants for his own purposes. When I pointed this out to him, he was very unpleasant.” On the next page Spielmeyer concludes that he learned that Wertham “has been speaking negatively about me and my department to his American colleagues. I would be very upset about it if they had not assured me his words carried little weight. It seems they don’t think very highly of Wertham either.”

Dr. Werthless seems to presume that every comment against Wertham should be taken at face value. We do not learn what exactly Spielmeyer thought Wertham had done that “exploited” his assistants.

Dr. Werthless illustrates several chapters from Wertham’s unpublished memoir, but overlooks a chapter that Wertham had devoted to one of the assistants at that Institute. Perhaps this had been one of the assistants that Spielmeyer had been thinking of. Wertham describes this man as “of sturdy peasant stock,” an “excellent meticulous worker” with “great mechanical ability” who “was always friendly and eager to be helpful,” and with whom he had many conversations.

This lab assistant was very upset by “a research study in which in order to get a continuity of blood samples small bits of the tails of white mice were cut off at regular intervals.” One night the assistant secretly opened all the cages so the mice could escape. After World War II, Wertham learned that this man who had been so “kindhearted to the animals” was as industrious as ever when the hospital began killing its patients in 1939, and he then used the technical experience he had gained there to operate the Holocaust’s gas chambers “with his usual zealous efficiency.” Wertham thought this story might illustrate “the real problem of our time.” How do we explain “a man with genuine compassion for animals” who lacked compassion for human beings?

Although Schechter and Powell represent Wertham as a self-promoting credit hog, in his scathing critique of comic books, Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham recognized Sterling North as the first of the anti-comic book critics. Wertham cited North’s “excellent and incontrovertible description” from 1940, in which he had observed that 70 percent of comic books contained material unacceptable to newspapers. Dr. Werthless quotes North’s denunciation of comic books as “sadistic drivel” from this same editorial.

Wertham added his voice to the anti-fascist tradition of anti-comic book criticism that North had started when he warned that by normalizing violence, crime comics were preparing the next generation to serve as stormtroopers or die as cannon fodder.

For reasons that can be found in Schechter and Powell’s book, Wertham has often been misremembered as someone who believed that reading comic books causes juvenile delinquency. Wertham denied that he had ever said or thought that, and wrote that his fundamental objection was that comic books were brutalizing their readers, dulling their empathy, and teaching them to take a sadistic pleasure in watching bad guys suffer. By addressing issues of empathy and sadism, Wertham’s work retains a contemporary relevance that Dr. Werthless, which closes with Wertham’s death in 1982, leaves unexplored.

Adam Serwer has coined a phrase that explains the growing political importance of sadism: “the cruelty is the point.” In his piece by that name, he highlights how “President Trump and his supporters find community by rejoicing in the suffering of those they hate and fear.” The article begins by examining a well-known 1930 photograph of the lynching of African-Americans Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Indiana, drawing attention to the white men who grinned sadistically when posing in photographs of lynchings. Shifting to current events, Serwer observes that “the Trump era is such a whirlwind of cruelty that it can be hard to keep track.”

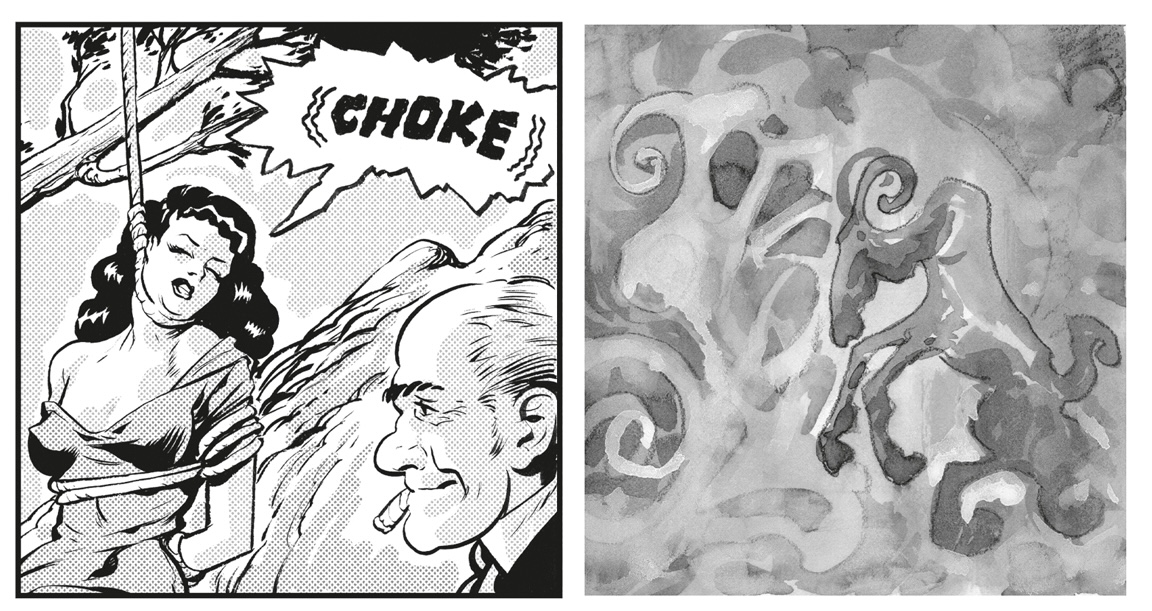

In Dr. Werthless, Powell and Schechter show, as one of their examples of the kind of comic book content that Wertham rightfully opposed, a drawing of a cigar-smoking man smiling contentedly as he watches a sexy woman with her hands tied behind her back being hanged. They do not mention that in his books Seduction of the Innocent, published in 1954, and A Sign for Cain, published in 1966, Wertham had connected the topics of comic books and lynching.

In A Sign for Cain, Wertham described a clinical study he had conducted in 1951 in which he observed that white children’s feelings of racial superiority and sadistic readiness for violence “were not spontaneous with the children, but were suggested by the adult world, including mass media, especially crime comic books.” One of the white children fantasized about tying African-American children’s hands behind their backs. Their comic books showed “dark-skinned people… depicted as savages to be beaten and hanged.” The following paragraph of Wertham’s chapter begins his discussion of “lynchings on racial grounds” as “one of the worst expressions of racial prejudice.”

In the end, Dr. Werthless concludes on an unsatisfying note, describing Wertham as a crusading fanatic who supposedly held a shockingly simplistic, monkey-see-monkey-do view of how comic books work. Still, comics fans generally have held Wertham in such low esteem that reading this biography might actually improve their opinion of him.

Readers of Dr. Werthless learn about Wertham’s wide-ranging, remarkably effective, progressive activism: his testimony against censorship, his co-founding and leadership of the anti-racist Lafargue Clinic in Harlem, his research that helped influence the Supreme Court’s decision to end racial segregation in schools, and his efforts to halt the U.S. government’s mistreatment of convicted atomic spy Ethel Rosenberg. Dr. Werthless also highlights Wertham’s strong compassion as a physician in treating his patients.

In one case, Schechter and Powell could have shown Wertham’s good side more quickly and powerfully if they had known more about his life. They spend four pages illustrating a letter from a distressed homosexual man simply to show the kindness of Wertham’s reply. Apparently, their search of Wertham’s archived papers had not uncovered that Wertham led a free clinic, sponsored by the Quakers and staffed by volunteers, that offered men who had been arrested for soliciting sex with other men an opportunity to receive psychiatric care instead of going to prison. In a 1948 radio panel discussion, Wertham explained that his approach sidestepped questions about whether homosexuality is a disease or curable, focusing instead on relieving suffering and helping individuals accept themselves. During the same broadcast, he also spoke against the entrapment tactics that led to many of these arrests.

In one case, Schechter and Powell could have shown Wertham’s good side more quickly and powerfully if they had known more about his life. They spend four pages illustrating a letter from a distressed homosexual man simply to show the kindness of Wertham’s reply. Apparently, their search of Wertham’s archived papers had not uncovered that Wertham led a free clinic, sponsored by the Quakers and staffed by volunteers, that offered men who had been arrested for soliciting sex with other men an opportunity to receive psychiatric care instead of going to prison. In a 1948 radio panel discussion, Wertham explained that his approach sidestepped questions about whether homosexuality is a disease or curable, focusing instead on relieving suffering and helping individuals accept themselves. During the same broadcast, he also spoke against the entrapment tactics that led to many of these arrests.

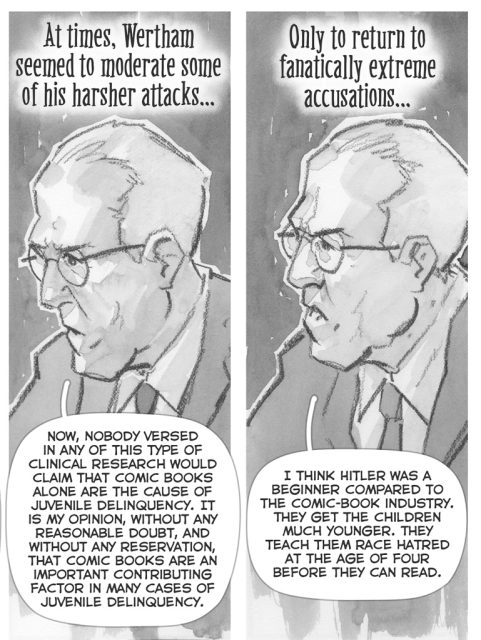

Schechter and Powell acknowledge that some of Wertham’s criticisms of comic books seemed reasonable. They say he also made “fanatically extreme accusations.” Their key example of this fanaticism comes from his 1954 testimony before a Senate Subcommittee, where Wertham declared, “I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry. They get the children much younger. They teach them race hatred at the age of four before they can read.” Comic book fans widely regard this statement — comparing the comic book industry to Hitler — as Wertham’s most offensive and stupid remark.

As with many panels in Dr. Werthless, this one presents an idea worth more careful examination. Comics historians have not asked who Wertham thought that Hitler was. Unlike those who imagine Hitler as the super-villain who started World War II, Wertham described him as a fairly ordinary man. In the story Wertham told about his argument with Kraepelin in Munich over a man who killed for a gold watch, he added as a background detail that Hitler was very active in that city back then, but not yet well-known.

Contrary to what one might expect from an author who studied murderers in such great, psychiatric detail, Wertham objected to attempts to psychoanalyze Hitler. Wertham dismissed the practice of psychoanalyzing someone based on hearsay evidence as both impossible and pointless. More importantly, he thought psychoanalyzing Hitler was dangerous, for reasons that are still relevant today.

In A Sign for Cain, Wertham condemns the “psychopathological diagnoses of fascist leaders” that direct attention toward the irrationality of individuals like Hitler instead of the cold rationality of figures like Thyssen, Krupp, and other German “industrial magnates.” These industrialists elevated Hitler to power because they accurately saw that he would advance their business interests by brutally crushing the labor movement and leading Germany into war. If we focus on the leader’s mental problems instead of these larger forces, we have wasted our attention on something that we can do nothing about.

In that chapter, Wertham also remembered that long before the Nazi takeover in 1933, a “hypernationalistic and superman-oriented” literature had conditioned the children who would become killers of “all those within the country who were officially declared inferior or subhuman, as well as any opponents abroad.”

In that chapter, Wertham also remembered that long before the Nazi takeover in 1933, a “hypernationalistic and superman-oriented” literature had conditioned the children who would become killers of “all those within the country who were officially declared inferior or subhuman, as well as any opponents abroad.”

In 2025, the old, stale warnings about the rise of fascism in America have taken on a sharper tone. It would obviously be absurd to blame the current events that many people find reminiscent of the Nazi regime on comic books or superhero movies. It is not absurd to grapple with and find new answers to the hard questions that Wertham raised about how our media diets shape us — both as individuals and as a society.

In the final chapter of Seduction of the Innocent, though, Wertham concluded that the effects of comic book on their readers’ behavior had not been “the most positive result of our studies.” He had learned that “comic books are far more significant as symptoms than as causes.” A society that ignores or defends marketing violent crime comic books to children also ignores or defends the other forms of violence that are built into its foundations.

To be fair, although Schechter and Powell include some interesting archival findings, with Dr. Werthless they focus on what is currently known about Wertham rather than conduct original, revisionist historical research. They have succeeded in distilling a lot of biographical material into an attractive, if not completely reliable, package.

If their book encourages a broader interest in Fredric Wertham, it serves a good purpose. While Schechter and Powell begin and end with the idea that Wertham held fanatical views about comic books, Dr. Werthless ultimately presents an interpretation that has already led some comics fans to a greater respect for his work. It can be approached fruitfully from a contrarian angle — to explore how well their portrayal either supports or challenges the idea that, for Wertham, the influence of crime comics on juvenile delinquency was secondary to a larger concern about preventing American fascism.

The post Dr. Werthless appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment