“In the limbo of the gutter, human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea. Comics panels fracture both time and space, offering a jagged staccato rhythm of unconnected moments. But closure allows us to connect these moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality.”

-Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: Blood in the Gutter

It’s rare that I read a comic and find myself struck by its poetry. While a good cartoonist’s work is often an excellent example of craft, creating a work of art cohesive enough to be called ‘poetic’ is incredibly difficult with the complexity of the many moving parts informing the medium. But poetic was the word that came to mind within the first ten pages of Jason Novak’s Kafka’s Manuscript (Fantagraphics, 2025). The book is a short, black and white story about author Franz Kafka’s final manuscript as his best friend and biographer, Max Brod saves it. The novel is entirely wordless, with only a single minimalist panel in the center of each page, usually depicting Brod and his suitcase carrying his friend’s papers. While the art is charming and emotive in only the way a true cartoon can be, the power of the book lies within the negative space surrounding each panel. There’s so much geographical and temporal space for the reader to digest what they’re seeing. That coupled with the simplicity of the art and the lack of words creates what I can only call a poetic meter.

It’s rare that I read a comic and find myself struck by its poetry. While a good cartoonist’s work is often an excellent example of craft, creating a work of art cohesive enough to be called ‘poetic’ is incredibly difficult with the complexity of the many moving parts informing the medium. But poetic was the word that came to mind within the first ten pages of Jason Novak’s Kafka’s Manuscript (Fantagraphics, 2025). The book is a short, black and white story about author Franz Kafka’s final manuscript as his best friend and biographer, Max Brod saves it. The novel is entirely wordless, with only a single minimalist panel in the center of each page, usually depicting Brod and his suitcase carrying his friend’s papers. While the art is charming and emotive in only the way a true cartoon can be, the power of the book lies within the negative space surrounding each panel. There’s so much geographical and temporal space for the reader to digest what they’re seeing. That coupled with the simplicity of the art and the lack of words creates what I can only call a poetic meter.

A lot of the magic of Novak’s work in Kafka’s Manuscript is dependent on a reader’s willingness to truly take the time to contemplate a single page. Comics, more than any other literary art form, offers a reader a great deal of autonomy about how much time they take with one page of a book. The intense minimalism of each of Novak’s pages increases the importance but also the tenuousness of that choice to sit with a page. It’s a big swing, especially in the era of internet-shortened attention spans, but the rhythm of Kafka’s Manuscript slows and hastens in waves, keeping the reading experience fresh in much the same way rhyme scheme might in a poem. Some scenes are meant to be lingered on, like Brod’s mourning period, like Brod hurrying to escape the Nazis, are dynamic and even suspenseful in a cartoony way.

Novak’s character work does credit to this demanding rhythm. The first two pages of the book are immediately intimate, introducing us to the close friendship between Brod and Kafka. The scenes’ emotional impact are of vital importance, without it the reader is set adrift with no emotional tether. It’s here that Novak’s simple cartooning style and absence of words first come to his aid. The quiet intimacy of the two friends reading and editing together is immediately recognizable before it’s achingly taken away from us on the next page when we see Kafka’s deathbed. It catches the reader, making us immediately invested in the lives of these characters.

Novak’s character work does credit to this demanding rhythm. The first two pages of the book are immediately intimate, introducing us to the close friendship between Brod and Kafka. The scenes’ emotional impact are of vital importance, without it the reader is set adrift with no emotional tether. It’s here that Novak’s simple cartooning style and absence of words first come to his aid. The quiet intimacy of the two friends reading and editing together is immediately recognizable before it’s achingly taken away from us on the next page when we see Kafka’s deathbed. It catches the reader, making us immediately invested in the lives of these characters.

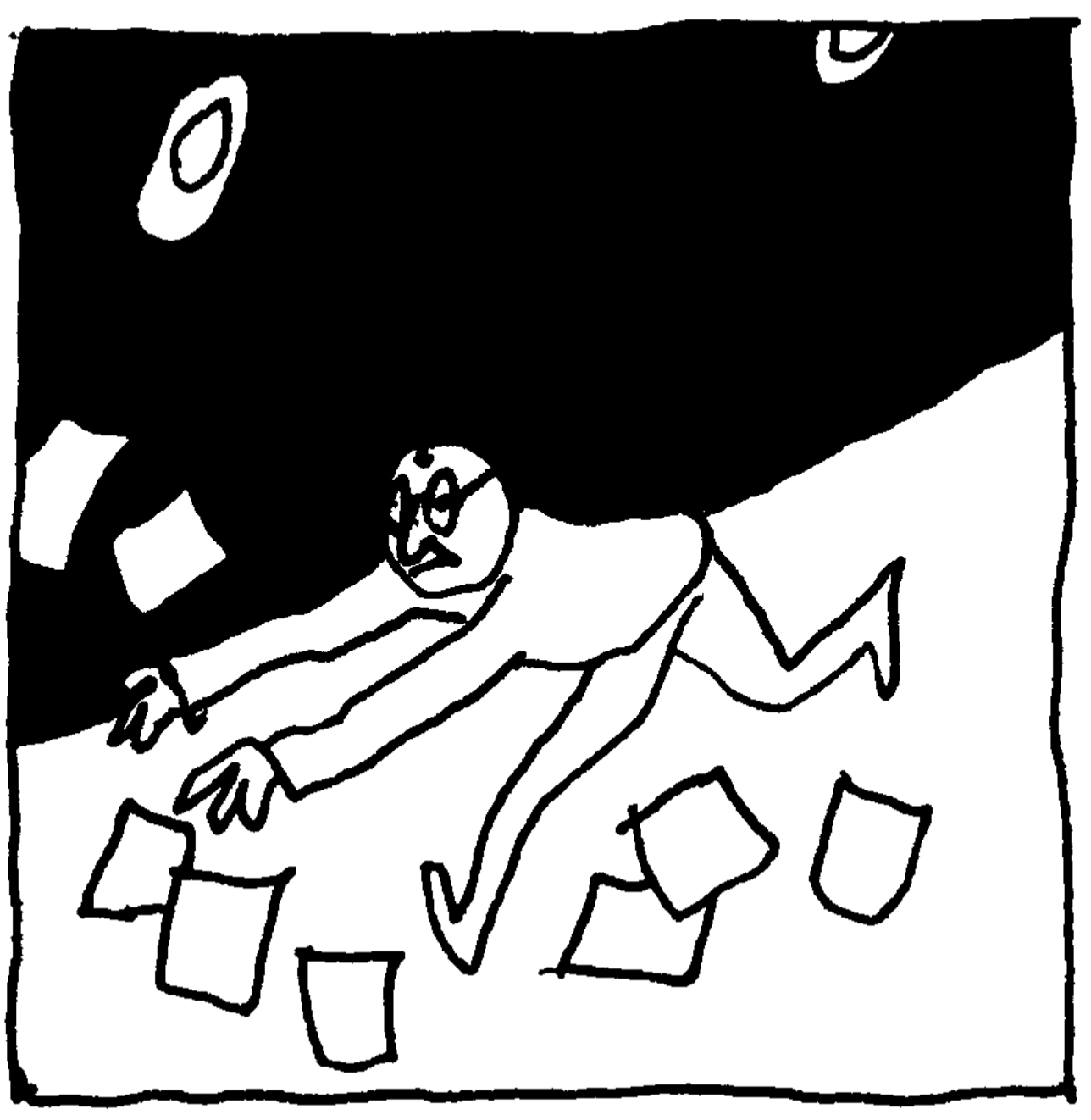

In other more action-driven scenes, Novak’s simple line work creates playful motion, with Grod running down stairs into the bottom right corner, drawing us to the next page only to find him peeking out of a doorway on the lookout for Nazis. The book is an endearing duet of tension and release within the structure of Novaks cartoon meter. Kafka’s Manuscript is an excellent example of the great strengths of a stripped down style in the hands of a thoughtful artist. By presenting his reader with art quickly understood on a surface level without any distractions, Novak invites his readers to choose to become active participants in the story, to elaborate and fill in the blank spaces between solitary panels. It’s refreshing to be given this freedom, this trust, when so much of our media spoon feeds us, not believing in our ability to opt into a story.

While Novak’s actual comic is entertaining and also fascinating from a technical point of view, his introduction to the novel is equally complex, and gives us a glimpse into a novel view on comics. The introduction begins by giving some biographical history of Kafka and Brod. The information is helpful, but it’s a mark of Novak’s cartooning chops that he could have simply provided us with his title, and the book would have been equally gripping and understandable. What’s most interesting about the introduction is Novak doesn’t use the words “comics” or “graphic novel” once in describing his book. Instead he calls it a “picture book” or a “novel,” before likening his choice to forego words to poetry, writing “Words are like boulders in a ravine. The more boulders there are, the more definite their pattern. But as the number of boulders increases, the less room there is to move freely. I think this is what’s meant when it’s said of poetry that the true meaning of a poem is somewhere in the space between the lines.” Normally I’m averse to the use an explicitly ‘literary’ vocabulary instead of a comics vocabulary to discuss comics. I’m of the opinion that it enforces a hierarchy between comics and literature(as I’ve just done) which is unhealthy for everyone. Yet when Novak does it, there’s no sense of a rejection of the comics lexicon in favor of the literary one. Denying that Kafka’s Manuscript is a comic would be more absurd than pretentious, given its publisher, and its undeniable use of comics conventions.

While Novak’s actual comic is entertaining and also fascinating from a technical point of view, his introduction to the novel is equally complex, and gives us a glimpse into a novel view on comics. The introduction begins by giving some biographical history of Kafka and Brod. The information is helpful, but it’s a mark of Novak’s cartooning chops that he could have simply provided us with his title, and the book would have been equally gripping and understandable. What’s most interesting about the introduction is Novak doesn’t use the words “comics” or “graphic novel” once in describing his book. Instead he calls it a “picture book” or a “novel,” before likening his choice to forego words to poetry, writing “Words are like boulders in a ravine. The more boulders there are, the more definite their pattern. But as the number of boulders increases, the less room there is to move freely. I think this is what’s meant when it’s said of poetry that the true meaning of a poem is somewhere in the space between the lines.” Normally I’m averse to the use an explicitly ‘literary’ vocabulary instead of a comics vocabulary to discuss comics. I’m of the opinion that it enforces a hierarchy between comics and literature(as I’ve just done) which is unhealthy for everyone. Yet when Novak does it, there’s no sense of a rejection of the comics lexicon in favor of the literary one. Denying that Kafka’s Manuscript is a comic would be more absurd than pretentious, given its publisher, and its undeniable use of comics conventions.

By acknowledging that his work requires a vocabulary beyond that of comics, Novak suggests something we’ve been scared to admit: that the two realms are inextricably intertwined. It’s difficult to imagine a world in which the language of literature and art criticism embraces that of comics and vice versa; we’re scared of sounding base, or pretentious in turn. But many of the best comics, and non-comics literature are demanding a more holistic understanding of both worlds. Works like Emil Ferris’s My Favorite Thing is Monsters or MariNaomi’s I Thought You Loved Me can’t be discussed without a more diverse critical language than that of only comics or only literature. What Novak has managed to do is quietly present an introduction whose language does not refute that of comics, but embraces that of literature, before following it up with a story that insists on a diverse critical framework to discuss it.

The post Kafka’s Manuscript appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment