The world is absurd in both large and insignificant ways, and more often than not the absurdity is not frivolous or playful, but rather dark and obscure. It’s an intimate absurdity that reflects back at our protagonist's own failings in Cornelius: The Merry Life of a Wretched Dog. Titled after its main character, the “wretched dog” created by Catalan cartoonist and animator Marc Torices, a general pessimism exists in the absurdity of events, but also in characters’ behaviors and decisions. It’s an intimate absurdity that reflects back at our protagonist's own failings.

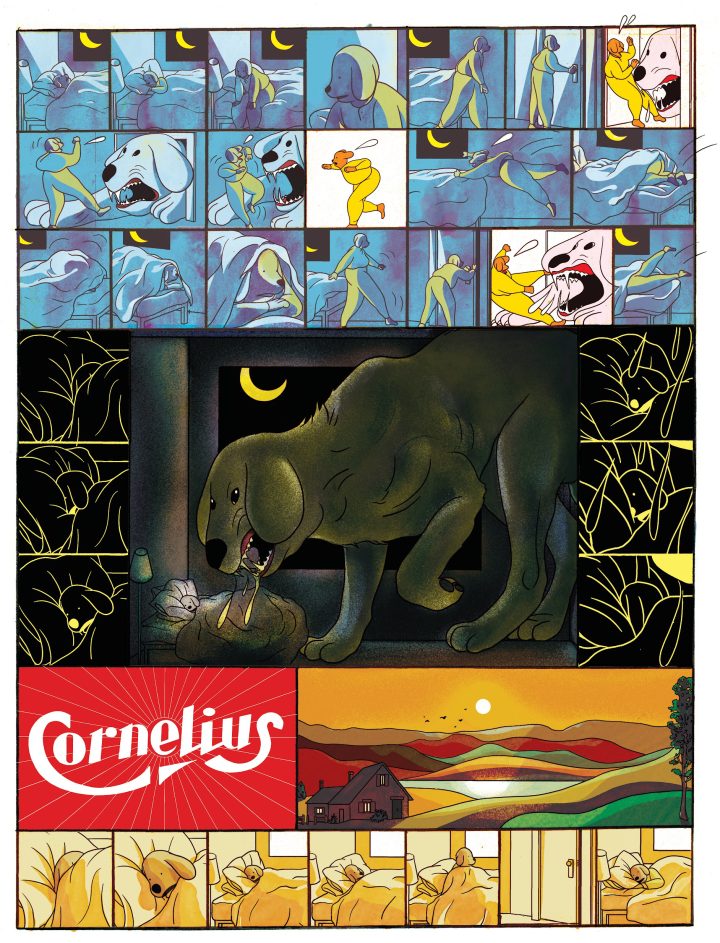

In Cornelius, the absurd is paired with a light gallows humour, if that’s not too oxymoronic a description. Literally gallows, given that in the opening sequence Cornelius, at this point a Clifford the Big Red Dog sort of character, rather than in his anthropomorphized version, gets his neck stuck in a noose.

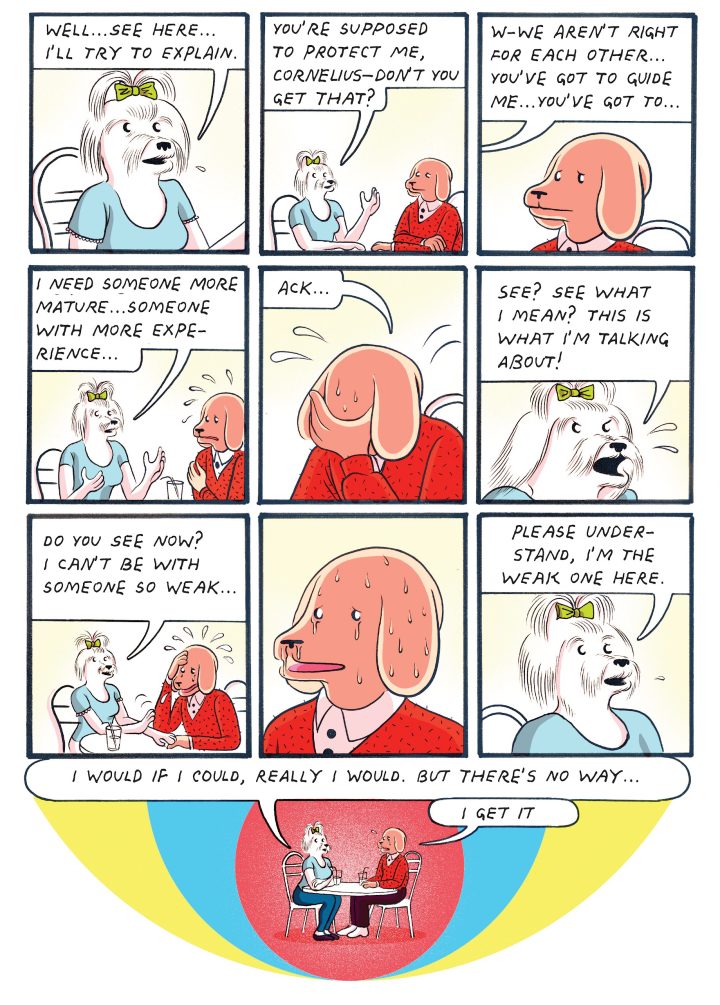

Our titular protagonist is a somewhat feckless and self-involved dreamer, working as a janitor at a sports center but with pretensions of being a writer and hanging with artistic types. His self-hating tendencies are compounded by the fact that much of his social life involves people that don’t tend to treat him very well. And he tends to distance himself from those who do treat him well, and often fails to treat them correctly in return.

This theme of failed relationships, not necessarily romantic ones, is heightened by the central dramatic event involving Alspacka, the niece of his boss, which I don’t want to spoil, but which is followed by Cornelius consistently making the wrong decisions, and making a bad situation worse. Torices has drawn a fever dream wherein agency seems to evaporate almost as soon Cornelius has a decision to make. He exists in a state of paralysis, rendered unsympathetic by his selfishness, and deepened by his reliance on characters he becomes obsessed with precisely because of their distance or success in performing the sort of personality he thinks he should have, or be associated with.

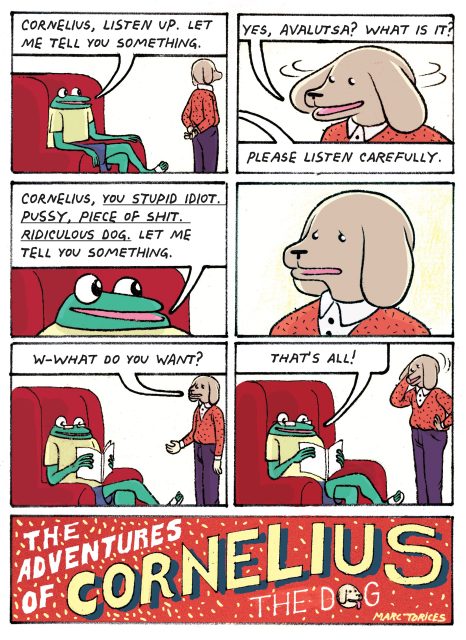

Torices renders all the characters as anthropomorphised animals. This heightens the cartoonishness of everyone’s actions, and serves as a good excuse for the artist to show off how good he is at drawing animals in this way (in this world the anthropomorphized dogs also have dogs as pets, but I guess that’s one of those things that’s best left unanalyzed). The informal language often successfully finds a balance between the literary qualities employed in a self-knowing fashion, and the vernacularity of the speech. Kudos to Andrea Rosenberg for this, who translated the work from Spanish for what has resulted in a handsomely designed hardback from Drawn & Quarterly.

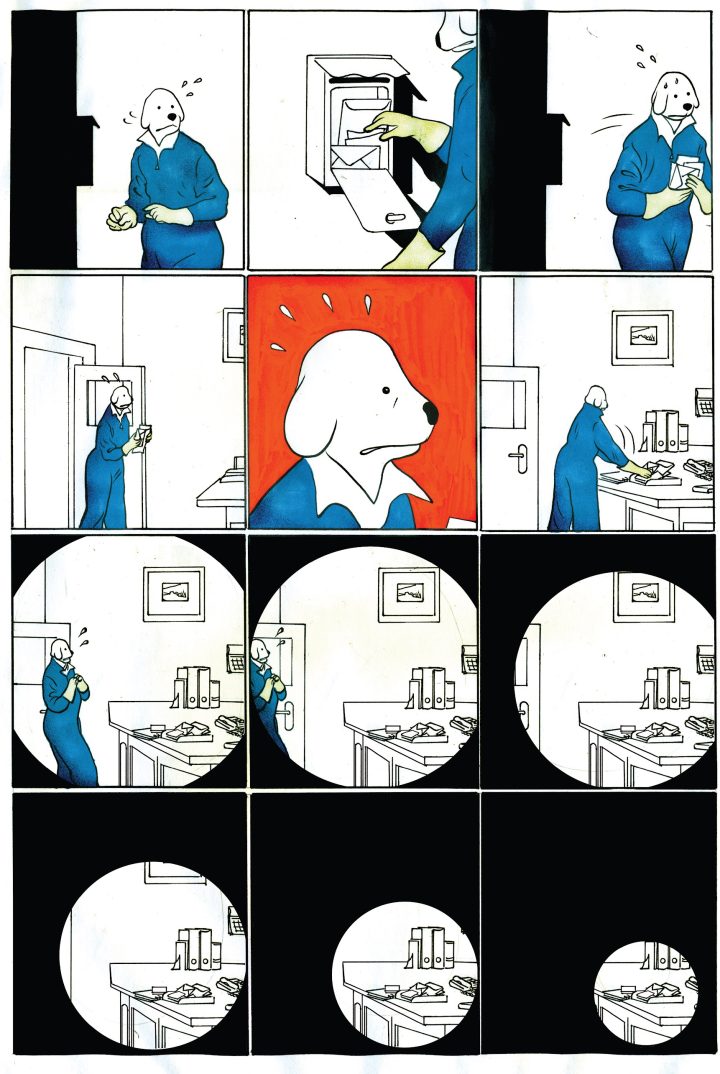

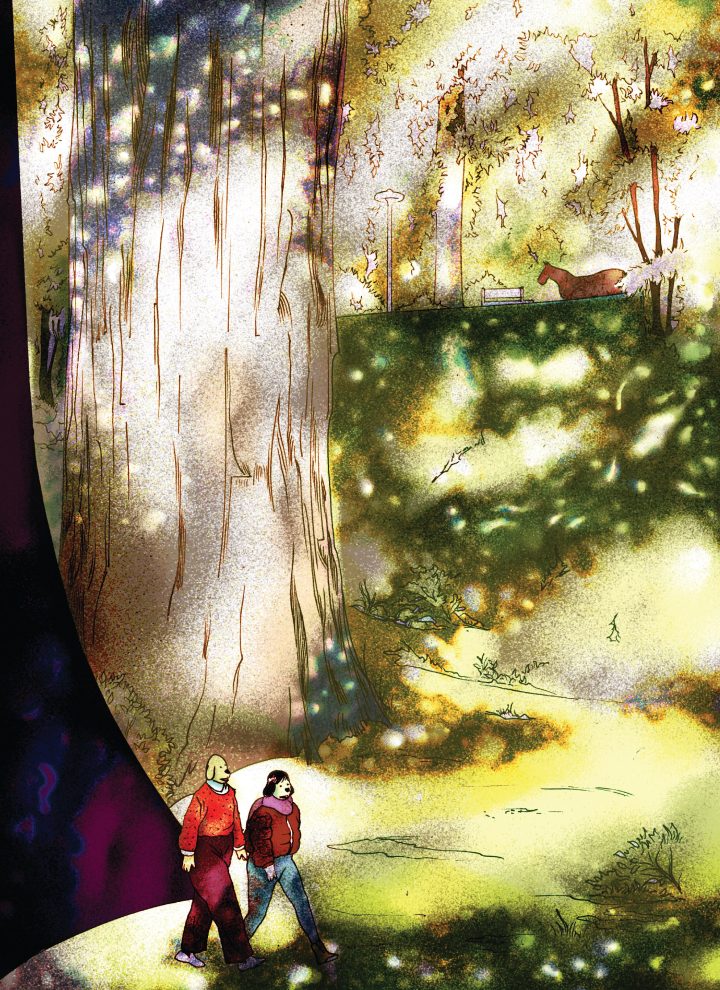

Retaining the major markers that allow them to remain recognizable, Torices is able to successfully represent (sometimes in the abstract) these characters in different styles. This is useful as he has a habit of jumping between illustrative and cartoonish styles once every handful of pages. There’s also pages of contained strips, each one boasting a different style. While this sometimes feels like code switching for the sake of it, at times it is employed in a way that heightens our sense of the characters’ perspective on themselves and each other. When Cornelius feels fragile or vulnerable he is shown in a childlike style. A particular gross-out sequence is rendered in a scratchy style, heightening the punky attitude therein.

Torices has been drawing Cornelius for over a decade at this point, and the character has often appeared in self- or indie published zines. Here that origin, as well as Torices’s interest in vintage comics, is apparent in the various title pages, each with unique calligraphic treatments, that make an appearance throughout the book. A meta commentary is also included, in the introduction and end notes, where a fictional editor introduces Cornelius as if he’s a millennia old icon, one who has been a major figure in the comics industry of a fictional country of Maiame. The meta jokes found within the end notes didn’t quite land with me; they feel like absurdity for the sake of it, though the joke is on me, as the fictitious editor is quoted as saying: “If you’re so smart, why are you reading comics?”

Torices has been drawing Cornelius for over a decade at this point, and the character has often appeared in self- or indie published zines. Here that origin, as well as Torices’s interest in vintage comics, is apparent in the various title pages, each with unique calligraphic treatments, that make an appearance throughout the book. A meta commentary is also included, in the introduction and end notes, where a fictional editor introduces Cornelius as if he’s a millennia old icon, one who has been a major figure in the comics industry of a fictional country of Maiame. The meta jokes found within the end notes didn’t quite land with me; they feel like absurdity for the sake of it, though the joke is on me, as the fictitious editor is quoted as saying: “If you’re so smart, why are you reading comics?”

It is a pleasure to indulge in Torices’s talents as an artist. His work in animation surely helps him in bringing his worlds to life with precise mise en scène, and an adroitness when it comes to using colour to imbue the pages with atmospheres and emotional impact. Narratively, the work revels in its own ridiculousness, as well as the ultimate portrayal of its central character as a pathetic figure, misunderstood by a public that misinterprets his tears, and declares him a “mensch!”

Cornelius is part of a long tradition of alternative comics in which the central character is an unsympathetic male who nevertheless subliminally demands sympathy thanks to his childlike qualities (I’m not sure it’s a good comparison, but Jimmy Corrigan kept coming to mind while reading this, Torices' and Ware’s shared interest in the packaging and branding of comics strengthens the association). One’s enjoyment of this story and its characters may depend on one’s patience with that trope.

The unsettling and unresolved elements of Cornelius may well be the point. The absurd is there to make us aware of the delicacy of our reality, and laugh at our efforts to make things make sense. Even with all the rationality in the world, people often do inexplicable things. In this instance, Torices’s mission as a cartoonist seems to have been to produce a book where the reader can get lost within the inexplicable, with a fine wretched dog as a mirror to our own absurdity and failure to act.

The post Cornelius: The Merry Life of a Wretched Dog appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment