If someone were to tell the story of Rea Irvin and The Smythes, they might not begin with dates or ink, but with people. With a man sitting at a drafting table, sleeves rolled, cigarette poised on the edge of an ashtray, and a quiet hum of industry in the air. They would make us feel the room, its gravity and its ease. Because The Smythes, after all, were never simply cartoons. They were portraits of a time when the world, or at least Manhattan, believed wit could be both armor and art.

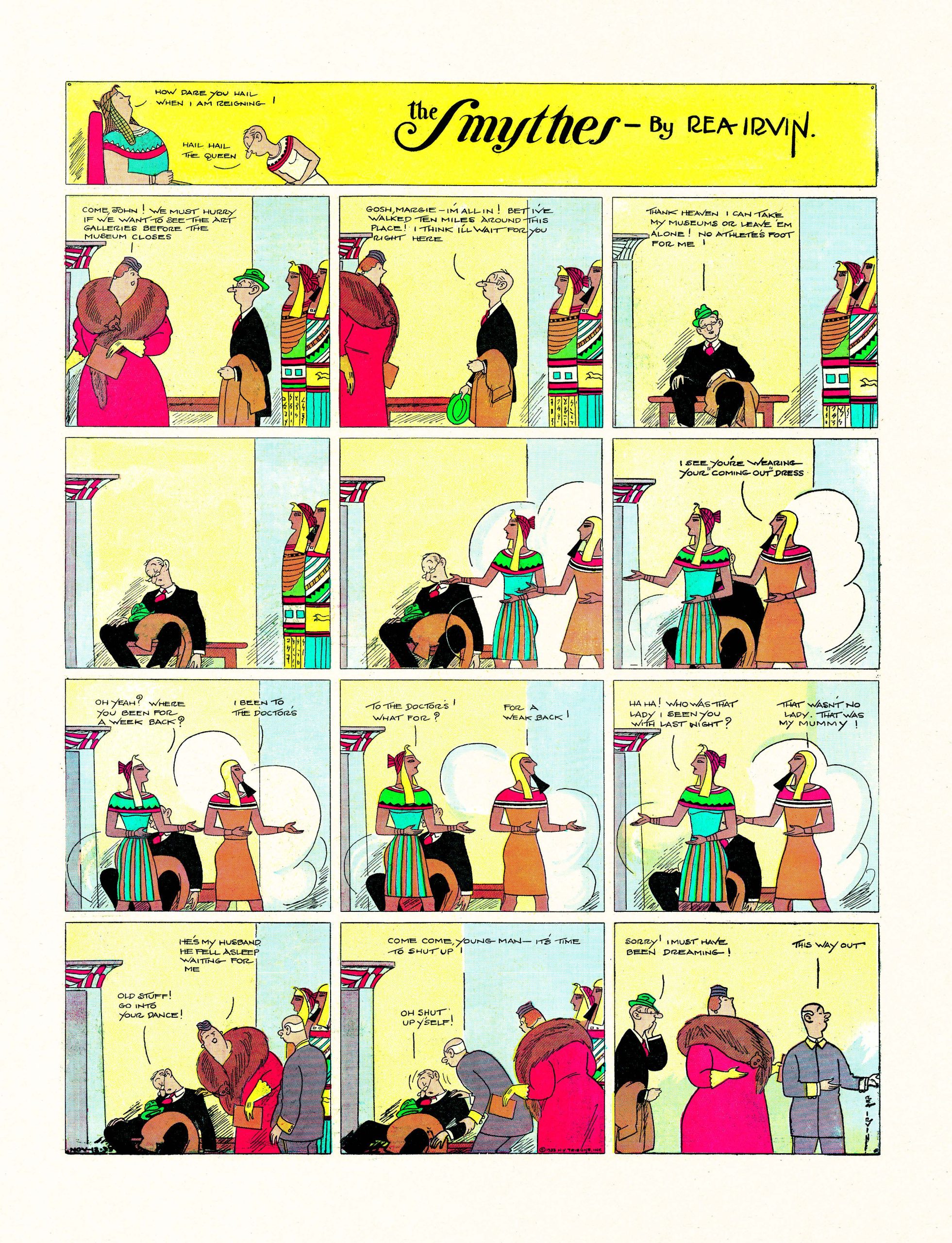

Rea Irvine's The Smythes, published by New York Review Comics, lets panels speak for themselves.

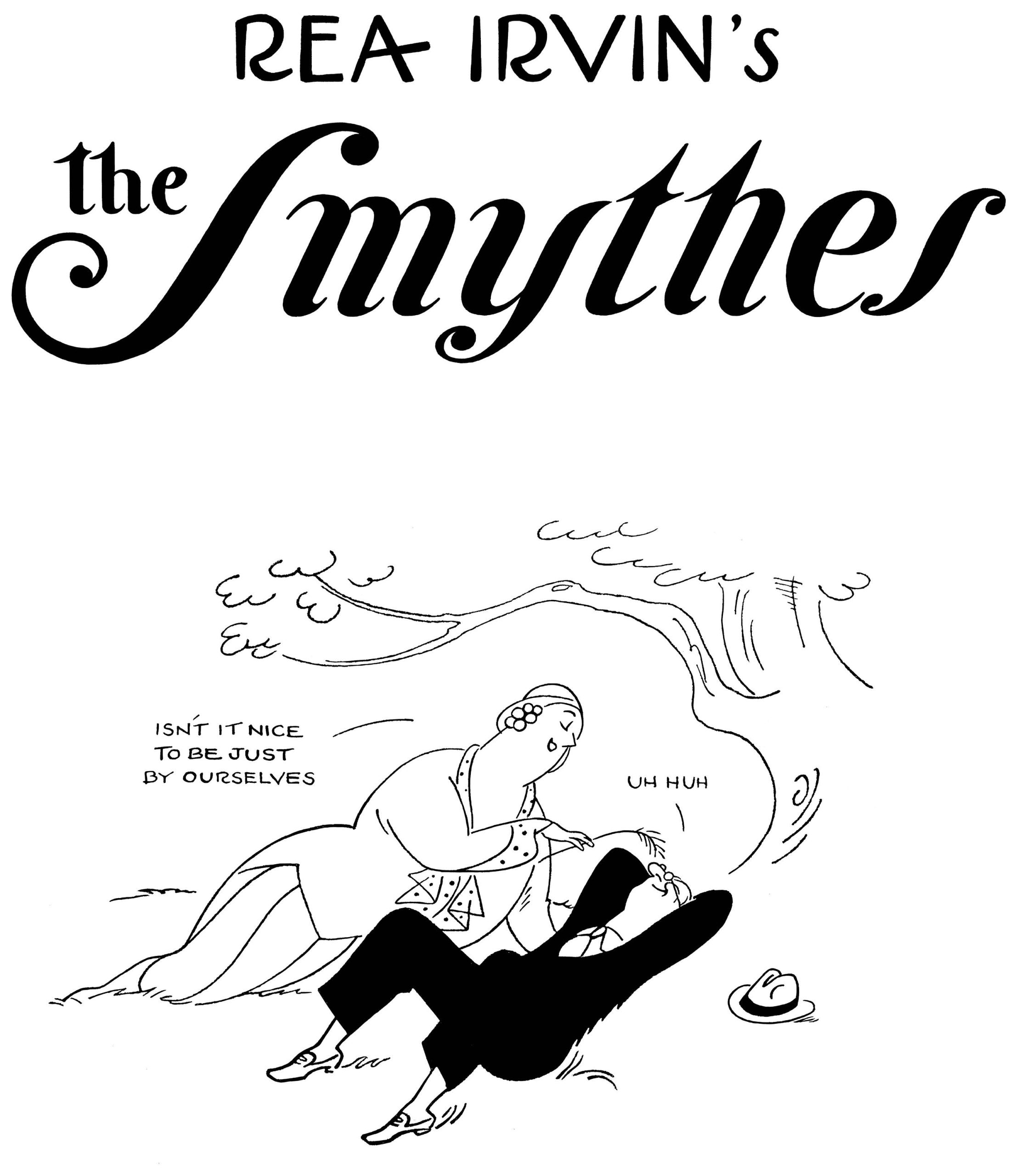

Rea Irvin, The New Yorker's first art editor, created The Smythes, a comic strip that debuted in The New York Herald Tribune in the spring of 1930. The strip was a domestic comedy; a husband and wife navigating the brittle charms and absurdities of upper-middle-class life. But under Irvin's pen, the couple became something more than a gag. They were a mirror, lightly fogged with irony, reflecting the anxieties and aspirations of postwar America. Mr. Smythe with his impeccable suit and mild exasperation, and Mrs. Smythe with her arched brow and exacting poise. They lived in a world where manners mattered more than money, where humor was the safest way to admit one's despair.

Irvin's name, if remembered at all, is usually tied to The New Yorker's first cover, the dandyish Eustace Tilley peering at his butterfly. But in The Smythes, Irvin's wit is sharper and more affectionate. The same sensibility that defined The New Yorker—urbane, ironic, self-aware—finds a warmer home here, in a marriage that is as much about love as it is about vanity.

The Smythes is not the kind of comic you laugh at so much as one you recognize yourself in, a mirror held up with a knowing smile. It's a portrait of a marriage (Margie and John Smythe), two people devoted to the art of seeming sophisticated, and undone, gently and repeatedly, by their own performances. Each strip unfolds like a stage play: the setting minimal, the dialogue crisp, the humor restrained but precise. Margie, in particular, is electric. She commands the page with that rare quality we call presence.

In the introduction, editors R. Kikuo Johnson and Dash Shaw highlight Margie as a mesmerizing force. "Margie glows on these faded pages, and it's her light, incandescent almost a hundred years later, that inspired us to bring back The Smythes." The comic ran for nearly seven years. Johnson and Shaw painstakingly handpicked selections from the first five years, ones that focused on Mr. and Mrs. Smythe as main characters. The selections are in chronological order.

R. Kikuo Johnson's Instagram reel (above) features him unboxing a copy of Rea Irvin's The Smythes in real time. It's glorious. Johnson's genuine elation, and the backdrop story of how the collection came about is a pleasure to watch. Johnson notes that "most people have only seen two of these that were printed in a book in the 1970s." The book, The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics (1977), features two pages of The Smythes in color, and Johnson wanted to see more. This led him to delve into microfilm from the New York Public Library online. He collected all six years of the comics. They were entirely in black-and-white.

"I was talking to Dash one day, and he was like, 'Why has this never been collected? We should do it.' And that seemed like a crazy idea. But here we are."

The Johnson-Shaw team found about 70% of the strips in color at Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University, continued their search, and the labor began.

"Phew! That book was a lot of work," Shaw wrote in an email. Considering the enormity of the task, there is a lingering question as to why The Smythes is so important. Did Rea Irvin have an influence on the editors' own work?

Dash Shaw on Discovery

"Lots of comics were around my house growing up so I had a surprisingly wide, eclectic comics education very early. I knew about underground, alternative, superhero, manga, etc. But I didn't get into New Yorker cartoonists until I was about 30. I'm 42 now.

"The New Yorker-style gag artists, particularly Garrett Price, were a fantastic new world for me to see. My interest in them kept me buoyed in some way– 'Oh, wow, there's all these other great cartoonists who were doing stories about regular people, regular places, relationships, and social archetypes'–it was incredibly exciting and helped me stay enthusiastic and engaged in comics. It came at the right time in my life. Garrett Price and his Drawing Room Only book in particular was a big influence on my last book, Blurry. Maybe if you held them side-by-side it'd be obvious. I'm not sure."

"Garrett Price's foray into newspaper comics is the brilliant White Boy that's been reprinted a few times in a few different ways, The Comics Journal, Art Out of Time, Sunday Press, etc...Through my interest in Price, I knew about his editor at the New Yorker, Rea Irvin, and Irvin's foray–The Smythes–but The Smythes hadn't been collected. So, I had to dig into The Smythes.

"I'm a comics lifer, so digging into these under-seen comics (which New York Review Comics has been so good about) is my way of staying psyched about comics. Smythes is a gorgeous, quite subtle and subtly ironic, comic that ran parallel to the other comics we know about. It was very touching to spend so much time with his work and spend a few years talking about him with Kikuo (and Lucas and Anika at NYRC.)

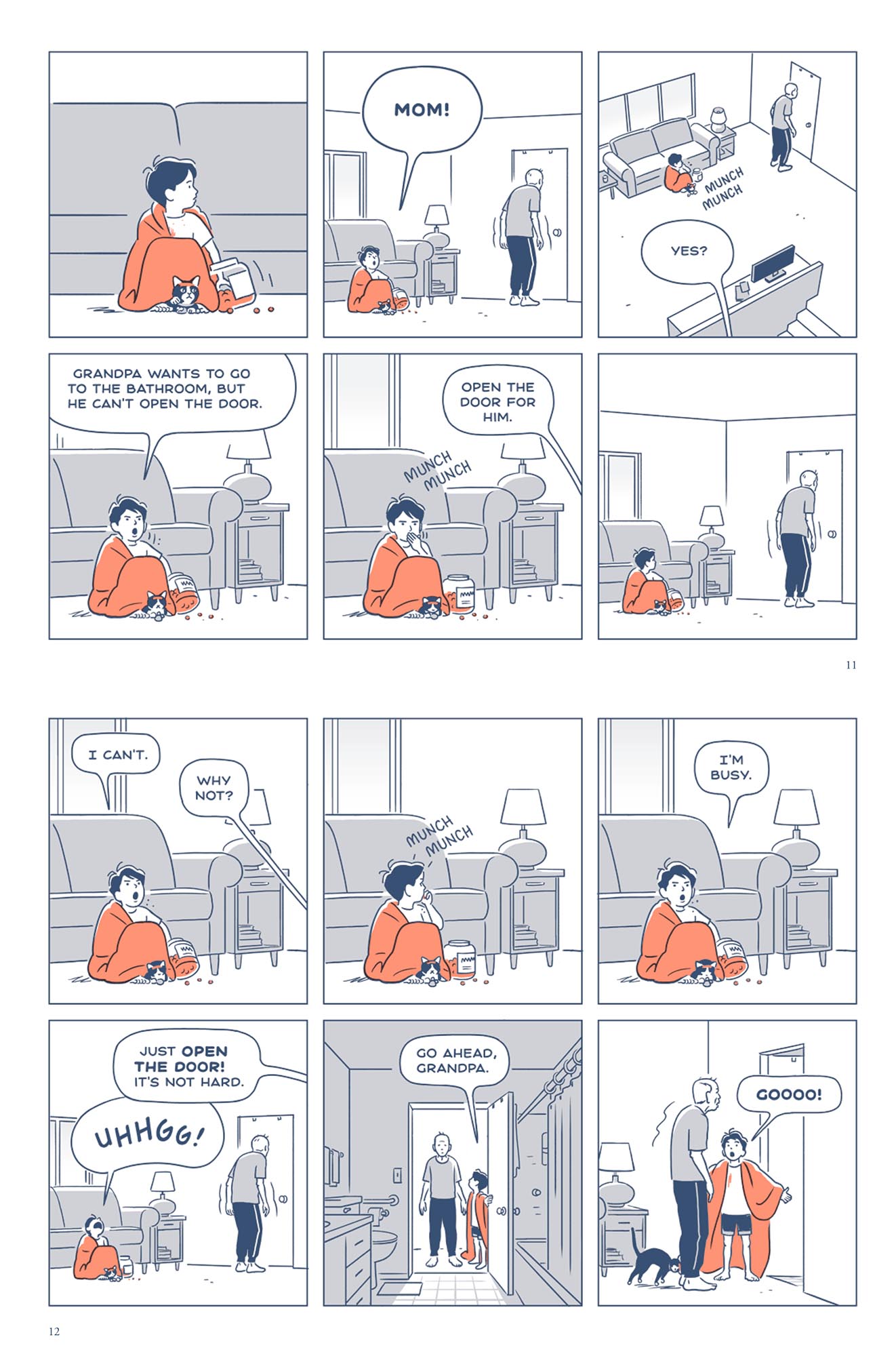

"Rea Irvin had much more of a direct influence on my friend and co-editor Kikuo, in particular on Kikuo's most recent book No One Else. He cited The Smythes as a direct influence on that book. You can sorta see it in the staging of the bodies and their subtle performances."

R. Kikuo Johnson on Rea Irvin

"There are definitely moments that I have been directly influenced by Irvin. I approached this cover ["Genuine Style"] as my version of Irvin's Eustace Tilley, a dandy who is not as sophisticated as he'd like to be perceived. I borrowed Irvin's signature nose-in-the-air profile."

"More broadly, I became obsessed with The Smythes while I was working on my last graphic novel, No One Else. In that book, the characters almost never say what they're actually thinking or feeling. Raw emotions are just under the surface, but they are implied rather than performed. I was actively looking for ways to portray the emotional scenes in as dry and distant a way as possible, and Irvin's The Smythes resonated with me in on two levels:

- The acting in The Smythes is so human and expressive while remaining nuanced and restrained. With a single line, Irvin imbued his characters so much personality and emotion without resorting to hyperbole to the degree his contemporaries did. I recognized that Irvin's subtle performances were capable of the kind of nuance that I hoped to have in my own work.

- The Smythes has an aesthetic that just feels, for a lack of a better word, 'adult.' Comics that feel this adult are rare historically. Having grown up on Marvel Comics, shōnen manga, and other adolescent stuff, reading The Smythes helped me temporarily purge some of the unhelpful influences that I absorbed during my many years as a comics reader. I used The Smythes and a few other older comics to trick myself into believing that I live in a world where mainstream American adults are interested in reading comics."

Rea Irvin: More Than Meets the Eye

What's striking is how quietly radical Irvin was. In the 1930s, when the comics page was full of pratfalls and pie fights, The Smythes offered a subtler comedy drawn from embarrassment, aspiration, and the deep absurdity of manners. Margie and John's humor lies not in slapstick but in the small humiliations of everyday life: the wrong word at a cocktail party, the awkward silence that follows a too-bold remark.

Irvin's line is both exacting and alive. He gives his figures weight and movement without crowding the page. Even the smallest background character; an aunt, a waiter, a stranger on the street, feels drawn from observation rather than imagination. His art borrows from Art Deco, from Japanese woodblock prints, from the elegance of early modern design, and yet it remains distinctly his own: graceful, ironic, and light on its feet.

There's something profoundly tender in these comics. Beneath the wit and style, Irvin understood that the performance of sophistication—like any performance—is a way of revealing longing. Margie and John want to be better, brighter, more worldly than they are. And in that effort, they become exactly what Irvin's line captures best, exquisitely human. And the genuine appeal of The Smythes rippled into Canada in the 1930s.

The Smythes in Montreal

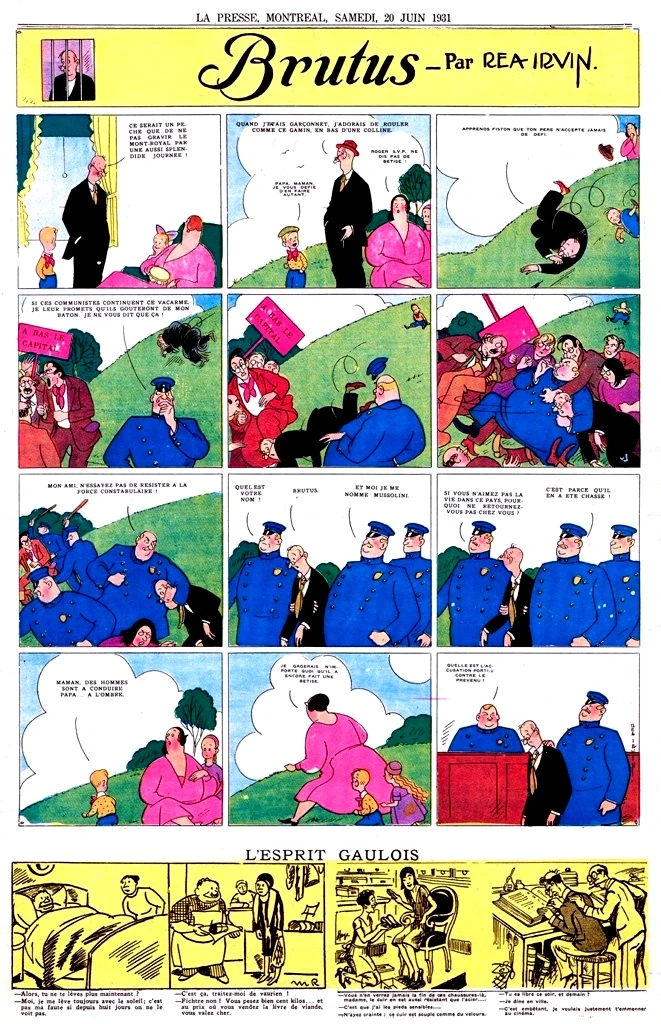

Brutus was the title under which Rea Irvin's comic strip The Smythes appeared in La Presse of Montreal during the early 1930s. Like its New Yorker counterpart, the strip centered on Brutus Smythe and his wife Margie, a well-to-do couple whose genteel domestic life offered a lens on upper-class manners of the interwar years. Irvin's drawings were elegant and economical, marked by clean lines and restrained expressions that conveyed both humor and unease.

In La Presse, Brutus reached a broader, more international readership, demonstrating Irvin's appeal beyond New York's urbane circle. The strip's gentle satire—its portraits of social striving, marital misunderstandings, and the comedy of good taste—translated easily across borders, reflecting Irvin's keen understanding of human vanity and the universal absurdity of polite society.

Caitlin McGurk's Afterward: From Collection to Character

Caitlin McGurk, a prominent comics historian and associate curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University, has contributed significantly to the preservation and scholarly understanding of early American comics. Her relationship to The Smythes is both scholarly and curatorial. The afterword, “Enter Rea Irvin,” shifts the book from a collection of elegantly curated panels into a fuller, more human story.

McGurk's portrait of Rea Irvin reads less like an afterword and more like the kind of story someone tells you on a long car ride; the sort that begins with a casual recollection and ends with you feeling as if you've known the subject your whole life. She lifts Irvin out of the polished mythology of The New Yorker—the monocle, the typeface, the dandy on the first cover—and settles him back into the rooms where his art was actually made. We see him at a drafting table in San Francisco, shouldering early loss and discovering the shape of his ambition; we see him on a ship, heading home as a stowaway; later, we find him in Manhattan studios and private clubs, threading his way through a city inventing itself as fast as he was.

McGurk gives us Irvin in motion—learning, improvising, performing, raising daughters, swimming in a handmade pond in Connecticut—and in doing so, she widens the frame around The Smythes. The strip no longer reads as a clever period piece but as the reflection of a man who lived across cultures and classes, who knew the heaviness of poverty and the lightness of social rooms filled with laughter. She shows how Irvin's characters, so elegantly drawn, carry both parody and affection in their bones: the foibles of the well-to-do rendered by someone who had once packed theater costumes on the road and later brushed shoulders with New York's cultural elite.

In McGurk's telling, Irvin is not merely a designer or cartoonist. He is a bridge between worlds, and his work becomes the truest record of that crossing. By the end, we understand The Smythes not as a relic from the Roaring Twenties but as the quiet, enduring expression of a life lived with curiosity, humility, and an ever-watchful eye. In the process, McGurk deftly weaves details into the text that pop: The New Yorker's signature typeface is called Irvin, after its designer; he was a high school dropout; the fact that he was an actor–all form an image of the man that ignites sparks of revelation. It all comes together. Not to mention the stunning images that follow.

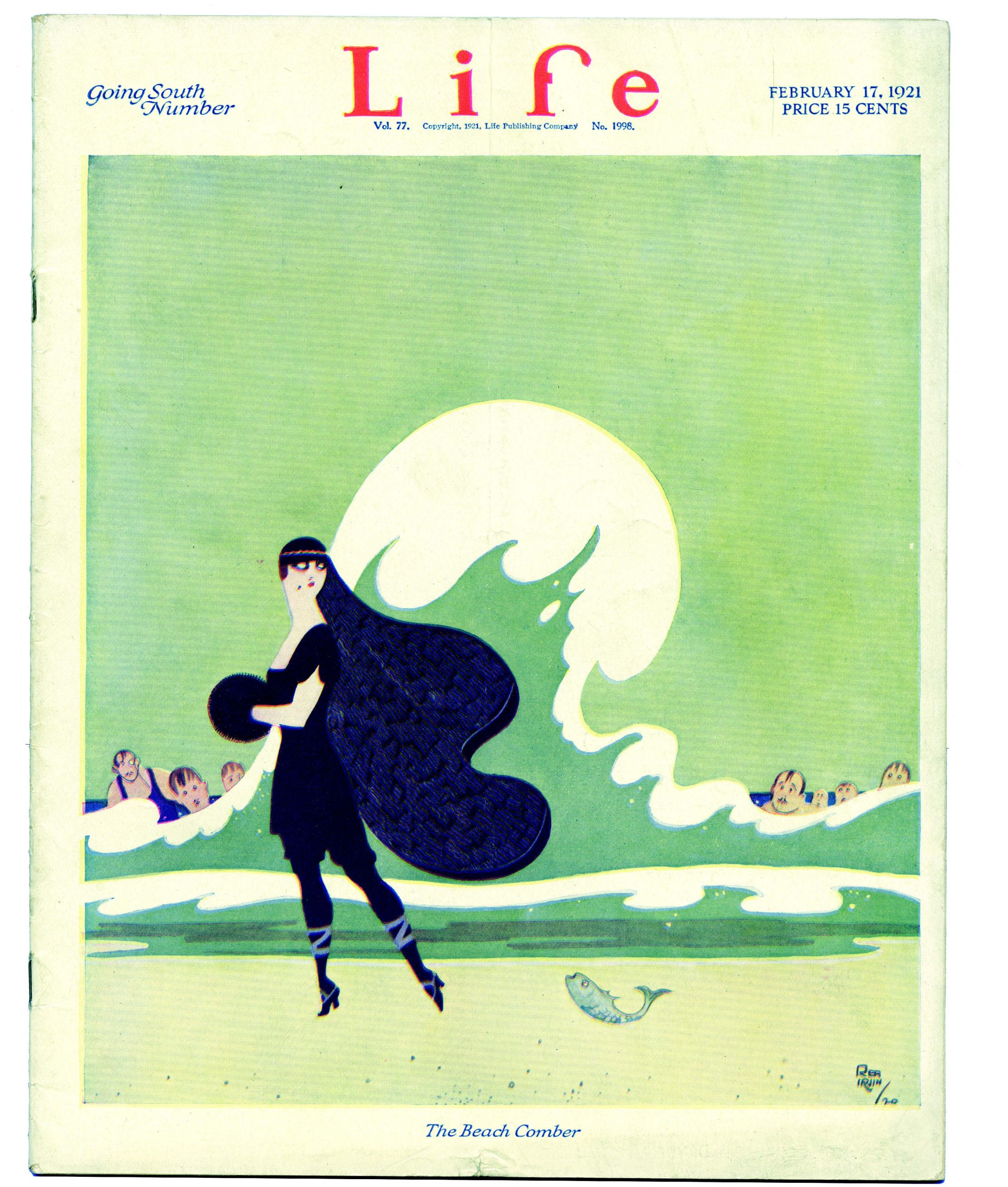

Yorker and The Smythes: fashion and social judgment. Irvin contributed dozens of covers during his ten-year stint as the art editor of Life." Pg. 142

When asked if anything about the process of writing the afterward, McGurk wrote, "Interviewing Molly Rea and Larry Rippee—Irvin's granddaughter and her husband—was immensely helpful and illuminating for me in gaining an understanding of who Rea was as a person, and some of the complications of his home life and marriage (which I opted not to include in the piece), in addition to her essential help with some of the general family history stuff. I was able to conduct a great deal of my research in newspaper archives, and was delighted to find so many references to Irvin's work as an actor, which was clearly just as much of a passion for him as his art was. It was also important to me to draw attention to the fact that Irvin was not a same-age peer as the other founders and contributors to the New Yorker, and really played more of a mentor role—including opting to be much more hands-off than many people tend to assume. He very specifically stayed away from the offices for all but one day per week."

The Smythes were not only a product of their moment. They were a quiet act of literary invention. Irvin's panels were small novels told in gestures. The lift of an eyebrow, the slump of a shoulder—these were his sentences. His dialogue was sparse, like dialogue in a good short story. All implication, no waste.

To read Rea Irvine's The Smythes now is to rediscover not only his forgotten brilliance but a quieter kind of humor, one that trusts its reader to see the joke without being told when to laugh. It's a reminder that irony and tenderness, in the right hands, are not opposites at all.

The Smythes' legacy endures in the DNA of The New Yorker itself; the urbane voice, the unspoken melancholy beneath the cleverness. They taught readers, and perhaps editors too, that sophistication could coexist with vulnerability, that laughter could be a way of telling the truth. It's also to encounter a rare tenderness in the work of a man who otherwise gave us the enduring mask of Eustace Tilley, eyeglass raised, butterfly fixed in his gaze. The Smythes were Irvin's reminder that behind every satire there's a love letter to a people, to a time, to the fragile, foolish business of being human.

The post The Quiet Wit of Rea Irvin: Rediscovering The Smythes appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment