“It is one thing, however, to remember, another to know. To remember is to safeguard something entrusted to your memory, whereas to know, by contrast, is actually to make each item your own.” — Seneca, Letters From a Stoic: XXXIII

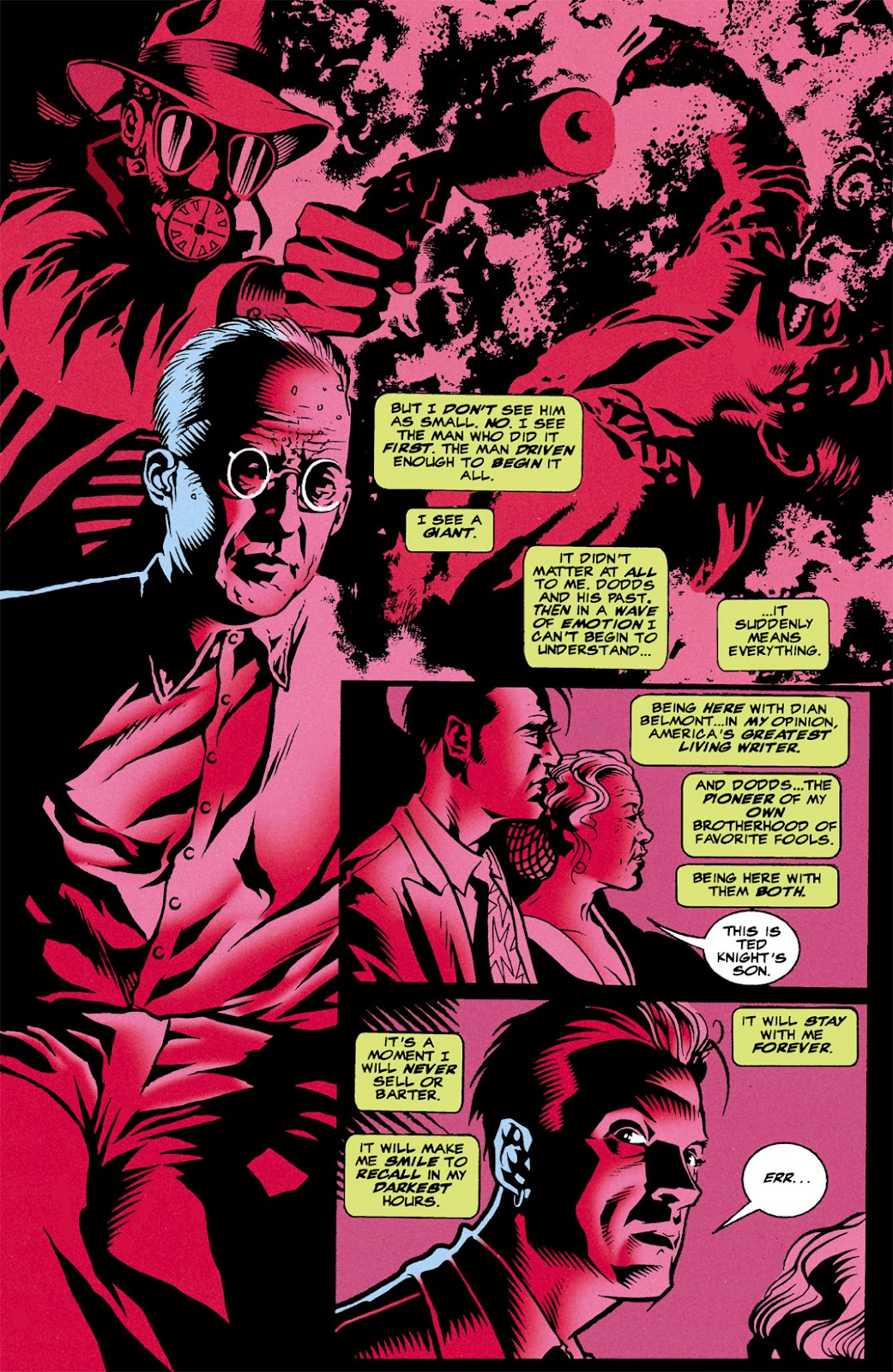

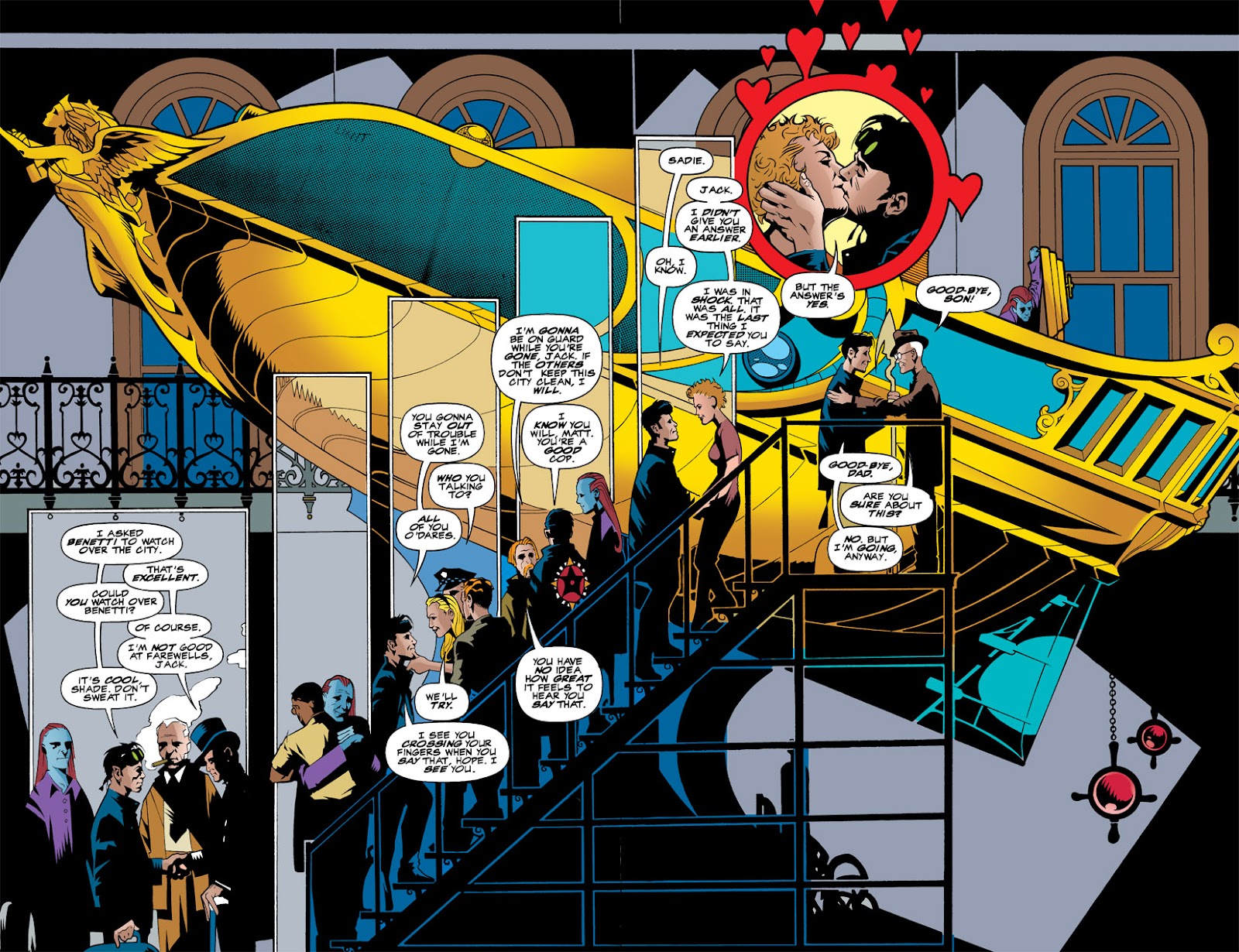

“Sand and Stars”, which ran in issues #20-23 of Starman, featured Wesley Dodds and Dian Belmont, and included a flashback drawn by Guy Davis. Since their pre-WW2 adventures chronicled in Sandman Mystery Theatre, the two traveled the world, had countless adventures, and Belmont received the Nobel Prize for Literature.1 When people talk about Starman being about nostalgia and the Golden Age, I think they’re remembering this arc, which received the Eisner Award for Best Serialized Story in 1997, a year the series and Robinson, Harris, and the rest of the team were nominated for multiple awards.

I was also a reader of Sandman Mystery Theatre and I understand why people loved it. The four issues are self-contained, can be understood by someone who hasn’t read Starman. It touches on the series’ main saga, involving an early caper by the Mist, which is the subject of the flashback and why Jack reached out. While visiting Wesley and Dian in New York, Jack stumbles onto another more recent crime involving a villain who is murdering businessmen, and a new luxury zeppelin.2

Tony Harris is at his best in designing and laying out the pages. Leaning into the art deco influences to illustrate this story of a “metropolis of now and then and never was,” as Robinson wrote of Opal City in the first issue. The color scheme is decidedly unrealistic, but functions much as all the art deco and the unusual angles that Harris uses for the story. It’s a little askew from the usual issues, but not much, and very different from SMT’s style and color scheme. The pages are beautiful to look at, bright and energetic with an incredible sense of layout and design and color.

Also when compared to the crossover Starman had with The Power of SHAZAM a year and a half later, it was actually good. The latter unfortunately was the cliched superhero crossover where two characters meet, have a misunderstanding, have a lengthy fight, then realize that if they had just talked like rational adults they would have realized that they were on the same side and could have solved the problem in a few pages. Of course if the characters had done that, there would not be four issues of story.

“Sand and Stars” is, from a certain point of view, what Starman did best. It’s a well-crafted story that is about history, that doesn’t just acknowledge the history of the DCU but revels in it, in a way that readers who know and love the characters can enjoy. Allowing even readers who don’t know the characters to understand and appreciate. It's fun and engaging and beautifully drawn. In some ways this is the precursor to a lot of the miniseries that Robinson has been making since the series ended. These self-contained, well-crafted genre stories that allow the artist to really put their stamp on the telling of the story. People remember this story as what Starman was. The problem is that the series was so much more.

***

I’ve talked a lot about Robinson is this essay. Perhaps too much. The comic would not have succeeded were it not for the artists with whom he collaborated, from Tony Harris and Peter Snejbjerg, who were the series regular pencillers, to the various others who filled in or drew "Times Past" stories, like Steve Yeowell, Matthew Dow Smith, JH Williams III and Mick Gray, Michael Zulli, Gene Ha, Wade von Grawbadger, John Watkiss, Teddy Kristiansen, Russ Heath, Craig Hamilton.3

One reason the series’ many fill-in artists succeeded was that Robinson was good at writing to their strengths. Think about Smith telling old superhero adventures as Ted gathers friends to fight Rag Doll, or Ted and Etrigan and Nazi saboteurs. Consider Hamilton drawing a psychedelic 70s adventure with Mikaal or a late 19th Century tale, both of them beautifully designed. Heath telling the story of how Brian Savage died. I could go on.

Rereading the comic, it was a great showcase for artists. It was never defined by the artists, not even Harris, who co-created Jack and drew roughly half the run. The fill-in issues worked because they were very much written to the artists, and stood out from the regular run. I mentioned earlier that one of Robinson’s great skills was the way he took so many tones and styles and managed to make them part of this larger thing. This is one of the things I meant.

Today the writer is considered the author of the comic and treated like that by companies.4 Rarely are artists filling in and written to and allowed to go crazy in the way that Robinson let them. It may have been in service to the writer’s vision, to the series’ structure and plan, but it was a vision that allowed for many approaches and a significant level of collaboration.

***

Reading through the first few years of Starman, I am reminded how much comics have changed in the years since. There are story arcs, single issue stories, two or three issues stories, issues that are designed to transition between story arcs and catch up with multiple characters. A time before comics would “write for the trades”. That shift — and I say this as one who since the 1990s would wait for the trade — has not been a good thing.

There are four and five issue arcs, the "Talking with David" issues, the "Times Past" issues. We meet Mikaal and Solomon Grundy, Jon Valor and Bobo Benetti. Matt O’Dare sees the light and tries to make things right. A Christmas special. The initial arc featuring the original Mist, an arc with Nash as the Mist. There’s the mad bomber Mr. Pip and the ongoing saga of the magic poster. To say nothing of the single issues which ease us out of one story and into the next in different ways. The first four years of the book, ending with Jack and Mikaal going into space are structured this way and are a lot of fun with a lot of momentum.

It would take a little effort to make it work in a normal format today, but in the same way that I see many artists and writers think about comics in terms of grids. Images in a grid arranged on a page instead of thinking about a page as a unit of space, thinking about page turns and that rhythm, the shift to abandoning the monthly format has had an effect on storytelling. Can I be nostalgic for something I never cared much about? Similarly to television largely abandoning the 20-something episode season to short series, we don’t just have fewer stories told, but there’s a loss of rhythm and a style and a way of thinking about story that’s been abandoned.

***

Culture shifted in the '80s and '90s. It can be startling just how much it’s changed. There is a reason why the comic series Planet of the Nerds5 involves a group of jocks from the 1980s who are cryogenically frozen and revived in 2019, disturbed to find a world where everyone is obsessed with superheroes and computers. I remember explaining the multiverse, a concept I knew from Michael Moorcock and comic books, when I was in high school, and the looks I got. Today it’s considered general knowledge. Like the superheroes that were once obscure, but are know recognized the world over.

This was the age when Wold Newton6 was everywhere. In part because copyrights were beginning to expire and so people were able to freely use and borrow in ways they hadn’t before.7 Also because works were being reprinted and shared and distributed in new ways. In comics, you had Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill with League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis and John Cassady with Planetary taking the concept in different directions. In fiction, Kim Newman was crafting his Anno Dracula series.

The '80s and '90s were also the era of the "New Narrative" movement, which was interested in using pop culture references, notions of authorship and physical space, of metatext, combining fiction and autobiography. A self-reflexive way of challenging narratives and storytelling. They were thinking about Brecht and how he sought to utilize the familiar to inspire a new consciousness

There are a dozen ways that Starman has nothing to do with what the New Narratives authors were primarily focused on and thinking about consciously, but as I work on this essay, I keep thinking about many of Kathy Acker’s books, Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker, Kevin Killian, Lynne Tillman’s Madame Realism pieces. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all this was happening at the same time.

This was happening during the rise of hip-hop, the prevalence of sampling. This was the era of the swing music revival. The musicians who’d defined this were influenced by far more than swing music, and some bands were “swing music” in a way that was tenuous at best. They were all grouped into “swing music” the way that a Renaissance Fair is a weird mishmash of cultures and time periods– and that’s before we get into the elves and fairies and science fiction costumes and people in street clothes.

That was the mood of the times. We were in a new era. The end of history and all that.8 It was the opportunity to rethink culture and everything that had come before. To embrace collage and montage and find new styles and approaches to fit this new time.

Starman may have been an outlier in comics, but it was not an outlier in culture.

***

One of the sources of superhero comics are old boys adventure tales. I keep thinking about this strange lineage of stories that stretch back to Daniel Defoe in the 18th century and Alexander Dumas in the 19th. That leads to Jack London to Joseph Conrad to John Buchan to Graham Greene to John Le Carre to Robert Stone to Viet Thanh Nguyễn.9

One reason they were boys adventures was because there were no girls allowed.10 Which brings me to Starman’s great failure. There are plenty of things that, in reading the entirety of the series over a short time many years later, may not hold up as well as one would hope. That read differently in chunks than monthly. That didn’t age well. Some plotting that didn’t work as well as they thought. All of this is to be expected. The big failure and disappointment of the series is the female characters.

I wrote earlier that the book is the story of Jack and Ted Knight, of fathers and sons. It does get into Jack and David’s relationship and the complex nature of brothers over the course of its run. That complex relationship of loving someone even though you may not like them. The series’ main problems is that none of the female characters have the depth or complexity of the male characters.

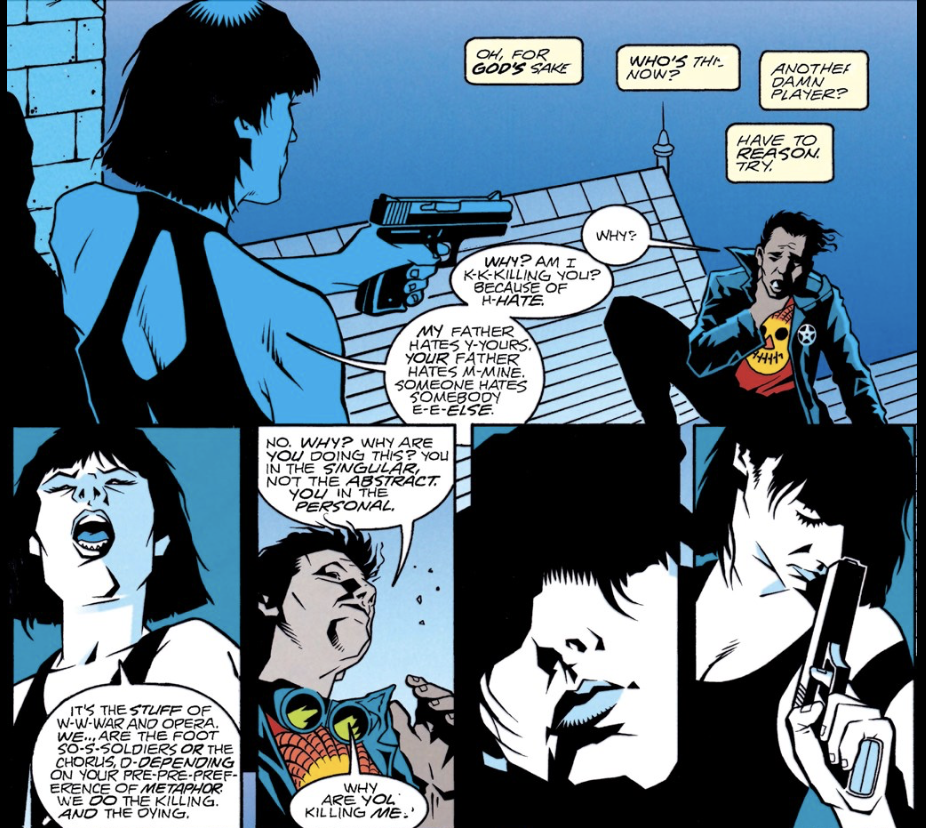

Nash, who after the first story arc becomes the new Mist, is the biggest disappointment. When we meet her in the first story arc she is the stuttering daughter helping her father and her brother. Her brother Kyle is the light of her father’s eye. The one who will become The Mist, the second generation supervillain who will take on his father’s mantle. Later in the series we see The Mist’s misogyny when he speaks of his daughter in a way that makes clear why she might have grown up stuttering and seeking a certain invisibility, even as she was desperate to gain her father’s approval. While she might say that she is taking on her father's mantle, it’s the death of her brother that inspires her and drives her.

Nash goes about being a villain in a familiar way, as though following a script. She stages heists. She kills a few superheroes. I think most characters in superhero comics tend to be one note, flat characters. Is the flatness of her character deliberate? For years I’ve heard about this need to make villains complicated. Yes, people who disagree with me have as deep and rich inner lives as I do. I’ve lived through decades of pop culture that was entranced by Hannibal Lecter and has regurgitated a million serial killers who are interesting and complicated. The truth is that they’re not. Political and business leaders literally laugh like cartoon characters when presented with evidence that they’re hurting and killing people. They may be sentient, but it’s hard to think of them as well-rounded human beings with complicated feelings and inner lives.

Is Nash the product of her environment? Incapable of being a full, complete person and playacting out relationships, imitating her father and other villains? Was she an intentionally flat, boring shell of a human being who lacks an inner life?

The most notable thing about her is that she rapes an unconscious Jack. She does for the purpose of becoming pregnant. Something we would see in the pages of Tom Strong from Alan Moore and Chris Sprouse a few years later. It remains uncomfortable thirty years later. Some of that is simply because it is rape. She does it to a man, which makes it about power as much as sex, which, yes, is always the case. Her plan, to get knocked up by Jack and then to raise their son to be a villain who will kill his father, is one of those plots that I guess makes sense?

I keep thinking about how in her very first appearance Nash invokes opera, which similar to superhero stories likes to toggle between epic myth and domestic melodrama.

Just as Opal City is the idea of America captured in a single locale, what if we took that metaphor of opera to the characters? Because then Starman becomes this story of the United States in the 20th Century in microcosm.

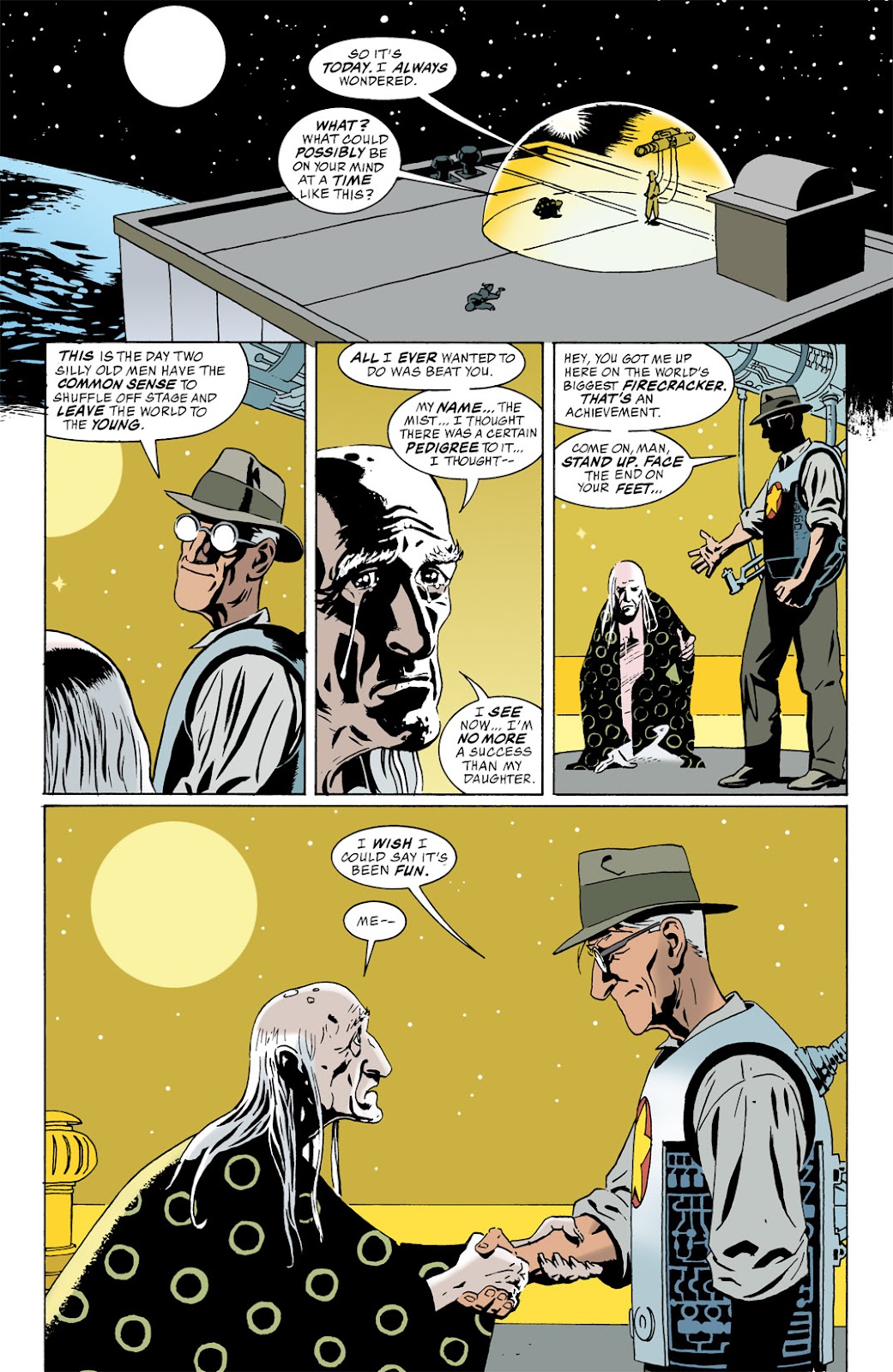

The Mist and Starman. Two elder figures, shaped by the First and Second World Wars, respectively, still alive at century’s end. Both heralded for their actions, but one emboldened by what he did during the war, the other weakened by it. The two men cast shadows over the decades, and over their children, each losing their firstborn son, who sought to take their father’s place. Each then replaced by their second-born.

In that framing, Nash’s plan to have a baby with Jack who will then kill Jack, makes a certain sense. The way that opera and myth have a logic to them.11

In the end, The Mist returns. While Ted Knight gave up his role and let Jack find his own way, we see The Mist driven by hatred towards not just his old foe, but his own daughter and grandson. And that hate literally consumes him, as he intends to destroy the city and everyone in it.

The city is saved by Ted, who sacrifices himself, after holding his grandson in his arms for the first and last time. Before encouraging his son to find his own path forward. In Ted’s final act of bravery, he uses a device to lift the Mist and the building with a bomb in it above the atmosphere where it can safely explode. In his last moments, Ted Knight becomes a star.12

Considering that the final issue of the comic was released in 2001, at the turn of the millennium, that’s not a meaningless fable.13

***

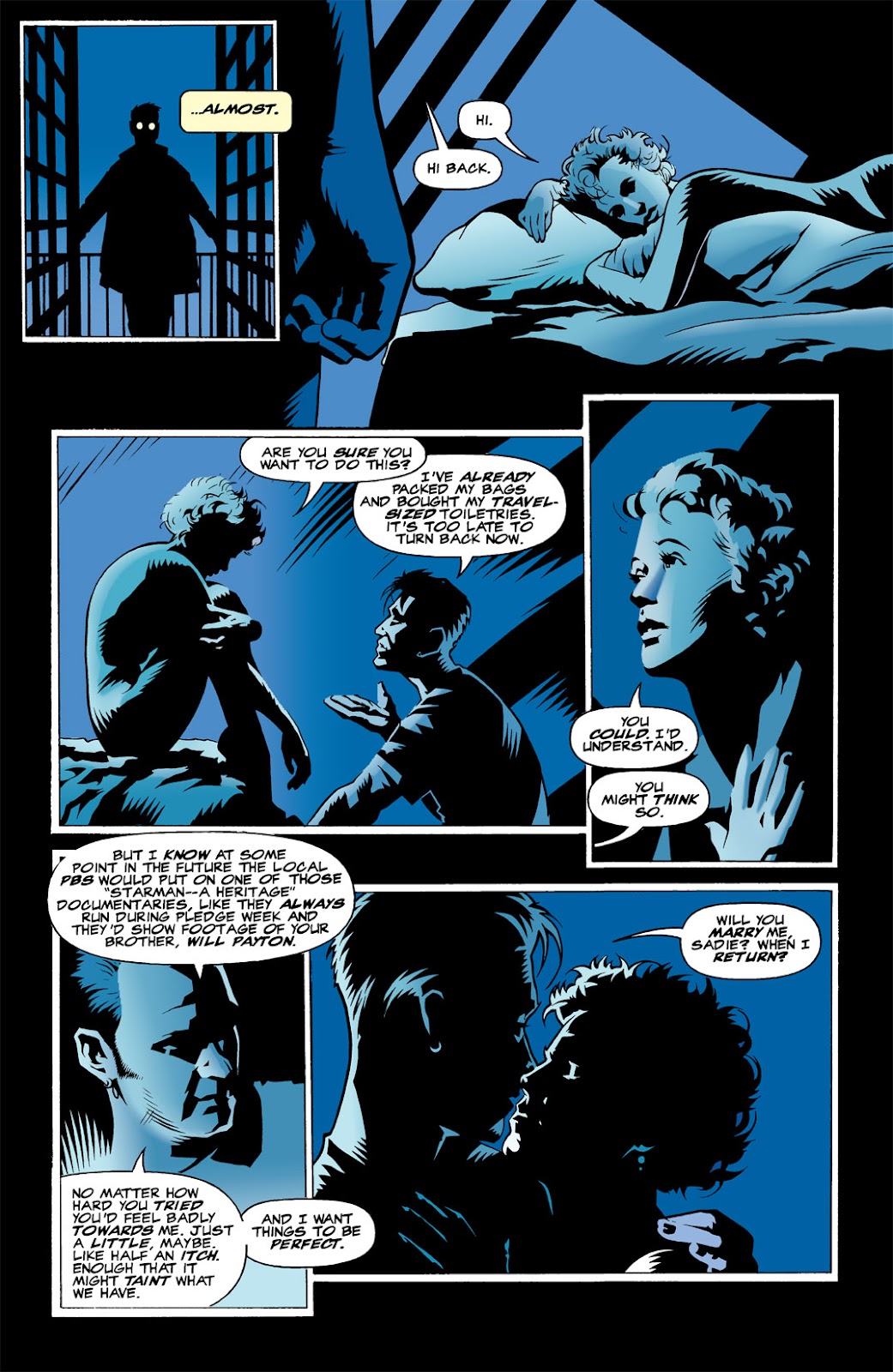

Perhaps the comic’s biggest failure is Sadie, or rather, the failure of Sadie as a character. She’s the character who Jack falls in love with. He goes into space for her in search of her brother who everyone else thinks is dead. He gives up being Starman and moves away for her. Not just for her, but she’s one reason he moves and realizes it’s time to give up being a hero. A character like that should jump off the page. Their relationship should burn.

I call her the comic’s big failure because she comes off fairly flat.

I kept thinking of Eve Babitz’s14 1991 essay on Jim Morrison,15 which is a great piece about the passage of time and nostalgia and trying to remember what was real even as a movie is being made, which undercuts the truth as you experienced it. One of the things that Babitz wrote about at length was Morrison’s partner, Pamela Courson,16 who "was the cool one. Everything a nerd could possibly wish to be, Pamela was. She had guns, took heroin, and was fearless in every situation. Socially she didn’t care, emotionally she was shock proof … whereas all he had previously brought to the moment was morbid romantic excess, he now had someone looking at him and saying ‘Well, are you going to drive off this cliff, or what?’”

Sadie should be more interesting. She must have been more interesting. The character must had have depths to inspire Jack the way she does. We never see any evidence of that on the page. I’m probably not one to judge. I’m not the sort who falls in love.

***

What would it have meant for Robinson to center Sadie and her romance with Jack in the comic?17 My gut says that the comic would have been cancelled. This is me being cynical, but I don't think that I’m wrong.

There are two stereotypes to acknowledge about romance stories. One is that the romance genre is largely written and read by women. The other is that it is a largely unserious genre that has led to women having unrealistic views of romance and men. Romance is a genre with tropes and expectations. Unlike other genres like mystery, crime, westerns, thrillers, etc., romance, which remains largely written by and about women, as a genre is not considered art and remains looked down upon.

I will admit to reading very few romance novels in my life. Like all genres, good writers are able to use tropes and expectations but can write thoughtfully about people. Great romantic comedies and dramas work because they understand their characters and while they contain tropes, they are telling the stories of people. Genre contains tropes and myths that are important to cultures. That's why they continue and continue to be passed on.

If romance books give girls and women unrealistic expectations, that implies that men have “realistic” expectations. Or takes as a given that whatever men think/believe is "the norm.” What are those expectations? How do we get those expectations? Supposedly women believe in a prince charming who will come along and save them. I won’t lie, some people think that, or want that.18 A romance is all about fighting over expectations versus reality, and the demands people place on each other, and how to live in the world. That’s not subtext, it is literally the text of everything from Nora Ephron to Jilly Cooper to Jane Austen. The bad books and movies may feature poorly drawn characters uttering bad dialogue, but it is the subject.

Romance in men’s stories, and boys stories, are often side stories. If they appear at all, the romance is secondary. The object of the romance is secondary as well. The relationship is secondary to the plot. Secondary to the character's passion. Secondary to the character’s destiny. What the main character does is the most important thing. The romance must fit into the man’s life and purpose that already exists. Men look for someone who believes in them, their passion, their purpose. Who will support them in their quest. The romance is not about negotiation and conversation, but about passion and choosing.19

Is this an argument that romance and relationships should be a minor aspect of our lives for everyone? Or that men should see romance and relationships as a minor aspect of our lives? Because whatever one’s thoughts on monogamy and compulsive heterosexuality, those are very different things.

In a romance story, a lot of the work of a relationship has happened before it ends. Maybe happily ever after is an unrealistic ending, but it required work and negotiation to reach that ending.20 In a boys adventure tale, none of that work has happened. A woman has come to rescue the boy from single-ness. Or is just there when he decides to stop being single. So much of the literature that we read as boys and men are about wish fulfillment. They’re not about navigating relationships. It reminds me of that famous Carol Gilligan quotation from In a Different Voice:

People used to look out on the playground and say that the boys were playing soccer and the girls were doing nothing. But the girls weren’t doing nothing — they were talking. They were talking about the world to one another. And they became very expert about that in a way the boys did not.21

Sadie seems to push against this. She asks her boyfriend Jack to go into space to find her brother because she has a feeling that he's alive. Like Charity’s gift of telling the future, it's unrealistic, but a genre trope we accept. Here it is part of Jack’s destiny. To be the hero he is supposed to be, to fulfill his destiny. As it has been written.22

***

I remember thinking at the time that the second half of the series wasn’t as good as the first half, dominated by two lengthy storylines. Tony Harris left with issue #45 when Jack went into space. After one "Times Past" issue, #47-73 were taken up by two story arcs: “Stars My Destination” and “Grand Guignol.” It’s a problem I have identified in a lot of works, where the second half or final third becomes so plot-focused that it loses some — or in some cases, all — of the appeal that the early parts of the story held.

This is also approximately when Archie Goodwin died. Robinson credited his former editor and mentor as a “Guiding Light” in the remaining issues of the series.

On rereading, I think that the story loses some of the momentum and feel of the first half, but I can see that Robinson is very conscious of this problem. The year that Jack spends in space is broken up with other stories. “Grand Guignol” is one large story but also is structured very consciously so that while it takes place over a year, it’s not a year-long story arc, but one that jumps around a lot, going back in time to explain things, focusing on different characters.

The series ends with issue #80, but I had forgotten that “Grand Guignol” ends with issue #72. Technically #73, I suppose, which is the funeral of Ted Knight. In the seven remaining issues, Jack goes back in time to learn the secret of the Starman of 1951, Russ Heath draws a "Times Past" issue detailing the death of Brian Savage, Superman visits, and Jack passes on his staff to Courtney, aka Stargirl.

After two lengthy and heavy story arcs, it’s a very leisurely conclusion, and I think that Robinson wanted that, and understood why that was needed. The two previous arcs were long for a reason, but it was exhausting. It might be easy to forget in this age of decompressed storytelling, but those issues managed to be ambling, but also pack a lot of detail and story. No issues that are really just a few pages worth of story padded out with scenes that don’t advance the plot and splash pages.

Sandman had wrapped up and similarly had a final story arc that stretched on for a long time. Longer than seemed necessary. I still thought that about Sandman, the last time I reread the series years ago. In Starman, I think Robinson was aware of the problems and handled them as well as anyone could. It was not unsatisfying. It’s simply that sometimes the weight the final act of the play might be necessary, might be inevitable, but feeling that weight is rarely as much fun as the early scenes. As any middle aged or older person can attest.

Theater-lovers will often say that the last act is never as fun as the first. It should feel inevitable and make perfect sense, but all the complications and consequences and weight come bearing down for the characters to confront. They are not left unscathed. That’s easy to forget in superhero tales, which so rarely have a third act, because they go on and on. A neverending tale where everyone escapes to fight another day.

***

I wonder sometimes what it means to love superhero comics as an adult? Heroic stories that lack a third act, a resolution, where one faces the consequences of all that has come before. Is this love for comics, which often translates into — if not paralleled by — a love of serialized and procedural stories. Adventure and crime stories featuring the same characters. Who may or may not age, for whom time may or may not continue, but one episode to the next, they continue having new adventures and solving new problems.

Much has been written for decades about the embrace of superheroes in the United States in the post-WWII era and what it means and represents. The embrace of superheroes in popularity writ large in the culture in the 21st Century is often seen in relation to a decline of American power. It remains to be seen what happens next. As the United States declines in economic and cultural power, will they continue to be embraced or will the genre decline?

That's for the moviegoing public though, which is different from people who visit comic book shops. Does our embrace and interest in superheroes represent an arrested development? There is a term I learned years ago, Peter Pans, for adult men who aren’t playboys or fuckboys. They aren’t against marriage. They might want kids. Maybe? Maybe not? They’re in no rush. It’s a bemused term tinged with sadness used to describe some men. I wonder if a love of procedural stories and superheroes, full of ongoing stories and last minute saves, is either a sign of such arrested development, or a contribution to it. Swimming in stories without a third act, without resolution and consequences, do we see that, even unconsciously, as a model in our lives? Does it prevent us from what we should be and need to be doing?

***

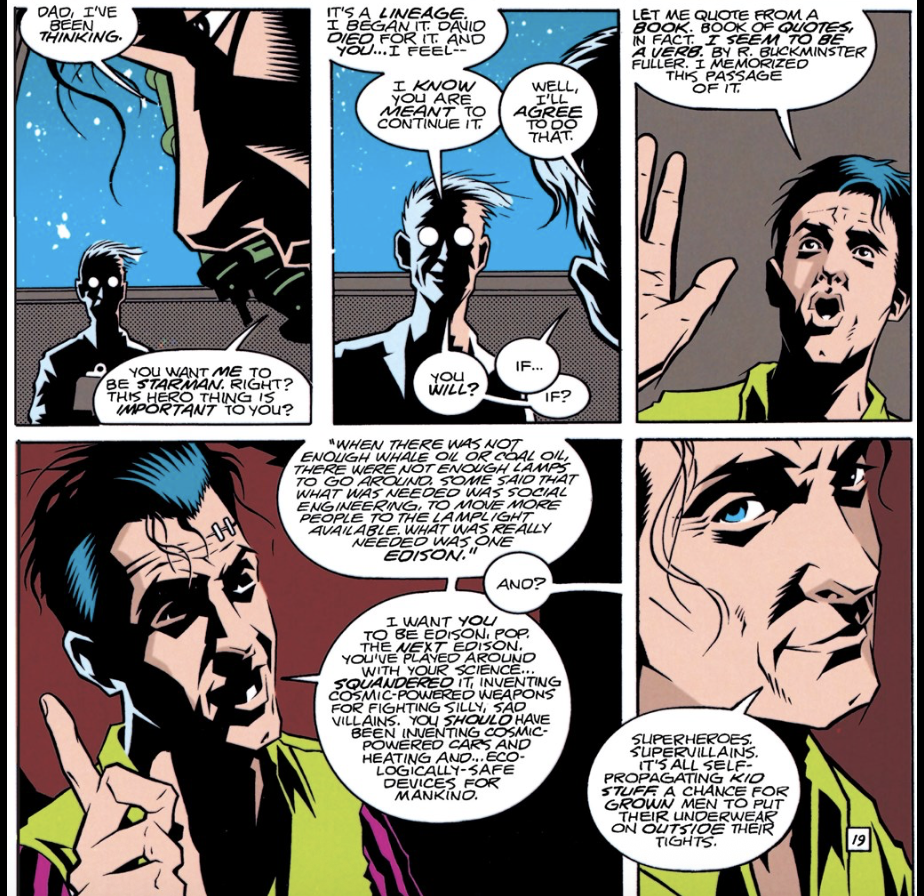

Robinson didn't create Jack’s father, Ted Knight, but in his hands, Ted becomes something quite different. It’s one thing to craft a villain turned amoral antihero like The Shade, but Ted remains an unusual and unique creation. Among superhero comics but also in Robinson’s oeuvre. If I had to point to one of the ideas and threads of this series that I had hoped that Robinson would explore later (and on rereading, how disappointed I am that he hasn’t managed to do more with) it would be with Ted Knight.

For all that was written about Jack Knight as a reluctant and unlikely hero, his father was an equally unlikely figure. Too intellectual, though The Shade and Wildcat both noted that he was more physical than one might have expected. He was also a man who gave it up. No fighting long past his expiration date until the last breath. He was happy to step aside and move on. Perhaps a foreshadowing of how Jack would go on to do the same? A model that one doesn’t have to spend one’s life chasing supervillains and that one can simply do other things?

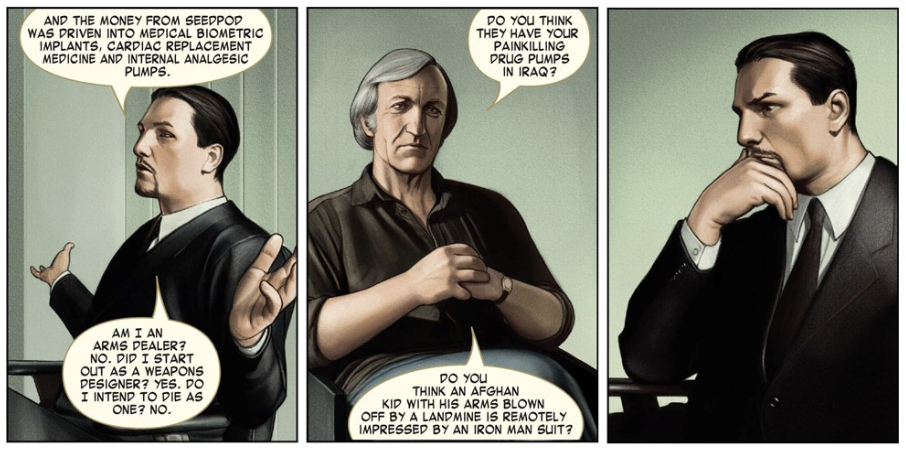

Ted was a fragile figure. I don’t mean that mockingly. He had a mental breakdown. One tied to the murder of Doris Lee, his first love, but also to his work on the Manhattan Project. Here’s where I think that Robinson’s Britishness come into play. I was reminded of the Warren Ellis and Adi Granov miniseries Iron Man: Extremis and the series’ take on the military-industrial complex. The idea that Tony Stark and his father were pushed into developing and building weapons from an early age. That this system doesn’t want the best and brightest to design new cities and energy sources, and bring about a Star Trek-like future. Instead it’s focused on weapons, and to a lesser degree, consumer goods. I would argue that this critique — even if just a few pages buried in six issues that consists largely of lengthy fights, an obvious reveal, ending with Stark having new fancy powers — makes this the fourth most subversive comic Marvel has published.23

Compare that to the Iron Man film, where the elder Stark’s role in the Manhattan Project is a part of why he’s so great. Rather than question the systems around Stark and militarism, instead we have movies that were used to help promote the military and American militarism and privatized war.

I hated the first Iron Man movie. That put me in a distinct minority among people I knew. The Afghanistan in the film had nothing to do with the actual country, but was instead Dick Cheney’s wet dream. The same cartoonish fantasy used to sell the Afghan and Iraq wars. A lawless place where Muslims of many languages and cultures came together to be evil terrorists whose ultimate goal is …something. Something evil, obviously, even if makes no sense. In Iron Man it involved obtaining weapons, attacking Americans, and rounding up villagers. They’re terrorists. We don’t need to think about who they are or what they want. They don’t make any sense.24 We just need to kill them. And we need bigger and better weapons to do it.

The second Iron Man film included an Elon Musk cameo and featured Tony Stark declaring “I've successfully privatized world peace.” How did we go from a Republican President pushing through tax cuts for the rich and planning destabilizing wars to today when we have … a Republican President pushing through tax cuts for the rich and planning destabilizing wars? Where people who once supported those wars now think they were a horrible mistake, and that the country’s real enemies are the people who protested that war believing it would be a horrible mistake.

Marvel and its military-backed, war-cheerleading superhero movies seem to argue it’s a much straighter line than a lot of people seem to think.25

This is why that idea, that the Manhattan Project was something troubling and morally fraught, marks Robinson as not American. I don’t mean that as a pejorative. In many circles it’s considered un-American to say that one should have moral qualms about the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan in 1945. To say nothing of what we owe to the many people who were exposed to weapons testing in the decades that followed.

As one who attended graduate school in Public History, we read extensively about the years-long process that led to the exhibition of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum in 1995. In the years leading up to the 50th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, curators and historians talked to hundreds of people and considered how to display the airplane and place the bombings in a historical context. Many people and individuals believed that acknowledging that dropping the bombs was controversial, or looking at the effects of the bombings, was offensive and revisionist history. The backlash to the proposal had an effect on the Smithsonian and other institutions for decades.

This was happening in the early 1990s when Starman was being written. Inserting the idea that Ted struggled with this for years seems small. An instance of pop culture commentary in a quick offhanded way making a point. Akin to James Bond making a cutting remark about Swiss bankers doing the right thing in The World is Not Enough.26 I would argue that it’s much more than that. This sense of morality and responsibility, which in Robinson’s eyes are tied to heroism, is at the heart of the book. It’s at the core of Ted Knight’s work in the series. At the end of the first arc, Jack challenges him to do more. To be better. The way that Jack puts it challenges the idea of superheroes as the ultimate expressionism of greatness, and instead as something almost selfish. That it is a boys adventure story, more akin to what we might find in the epic of Gilgamesh as opposed to how superhero comics portray their subjects. Making clear from the very start of the book that being a superhero is not and should not define one’s life.

In 2002, Joe Casey and Dustin Nguyen launched Wildcats 3.0, which centered around the character Jack Marlowe and the HALO company trying to build a better world. The corporation as a superhero. Employees who might be superheroes and be called upon to do things that are legal and not, but in the service of a larger project, which felt of its time, when Silicon Valley was something dynamic and innovative. It was the era of Google’s corporate motto, “Don’t be evil.” Google after all came into being because two graduate students had literally built a better mousetrap. That's what technology offered. What Silicon Valley represented.

It was a theme and a plotline that was echoed to much lesser effect in Matt Fraction and Salvador Larroca in Invincible Iron Man in 2008.27 I noted my objection to the Iron Man film earlier, and here I will note that the internet had not entered its enshittification28 stage by 2008, but in retrospect, the signs were there.

***

While Starman was coming out monthly, Robinson was busy with other projects from the random comics gigs from WildC.A.T.S. and Vampirella and Ash.29 He wrote a Batman/Deadman graphic novel and a number of issues of Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight. I don’t know what happened with Leave It To Chance and why it ended so abruptly. I think that it’s sad that the book wasn’t picked up and repackaged by a publisher, like Scholastic did with Bone. I don’t know why the collections haven’t been kept in print.

Maybe I’m alone in thinking that Robinson’s older work like London’s Dark and 67 Seconds and a collection of the two books he made with Phil Elliott should be reprinted in nice editions along with some of the shorter comics he’s written over the years. He also wrote the ongoing series Firearm, but we’ll all be dead before Marvel lets a collection of any Malibu comic happen.30

More recently he made a series with J. Bone, which didn’t quite work. His Scarlet Witch series, which featured a new artist each issue was enjoyable, but the overarching plot of it ending with her returning to the Avengers was the least interesting aspect of the book. Grand Passion was a crime comic that deserved more attention than it got. He wrote James Bond: Felix Leiter, though I don’t know why a sane publisher thought fans wanted a comic about the 12th most interesting Bond character.31

I think of the first stage of Robinson’s career as concluding with Starman, followed by the relaunches of Hawkman and JSA, both of which he worked on for a story arc before taking a break from comics. I thought that gap was from trying to follow up on Hollywood opportunities that came after the release of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen film, which Robinson adapted. For all the griping about the changes made from the comic, on rewatch, it’s not horrible. No worse than most mediocre big budget blockbusters.

The scenes between Tom Sawyer and Quartermain provide an emotional spine to the narrative, which the comic lacked.32 Some other character bits are good. The film relied far too heavily on CGI. Blade, director Stephen Norrington’s previous movie, was not great but had style and good fight scenes. That film was marred by its use of CGI, which looked bad at the time and worse today. League wasn’t good, but was it any worse than other big blockbusters of the era? League is like the superhero work that Robinson has been doing in recent years. It’s not his idea, he gets a lot of notes, and he manages to craft something that’s not bad. That’s better than it needs to be. That’s interesting.

It’s also not “HIS.”

I say that even though I know it’s bullshit. This idea that all work, all art, must be personal and something only you could create is one of the pieces of advice that everyone hands out to aspiring artists and writers. It’s good advice, but also, there are bills to pay.

I was eager to read Batman: Face the Face, the first comic of Robinson's in a while, and was just unimpressed. Anyone could have written that. This is part of what was behind Airboy. The comic got attention for the nasty transmisogyny, which I will not defend, and honestly sits uncomfortably in the story. I think it’s worth noting just how angry and nasty the book is in general. I won’t say it’s Robinson lashing out at the comics industry and himself, but it kind of is. It might open with a sad and almost over-the-top tone, but I think that obscures the sadness at the heart. This feeling that his career has come to an end, his marriage has come to an end, he hates himself, and feels like a failure.

As someone with career and money troubles, who lives alone and has been known to wallow, who has had depression and suicidal ideation for most of my life, I can relate.

I’m guessing that Robinson didn’t invent that above dialogue out of thin air, but quoted it directly from someone. How sad is it that this was what so many editors took away from that? How pathetic that people who make comics had only the most surface level understanding of the book. After Starman wrapped up, Robinson stepped away from comics briefly and it’s hard to blame him if this was how the industry responded. I don’t think he meant for comics to be a stepping stone to something else, something “better,” but he wrote a great comic series and got to conclude it on his own terms. Why should he turn around and try to do that again? He tried to do something else. If editors didn’t understand what he had accomplished, why work with people who don’t appreciate you?

***

More recently Robinson seems to have had a career resurgence. Why exactly I could’t say but it’s been great to see one miniseries after another come out with a variety of artists in different genres: ‘Patra, Welcome to the Maynard, Los Monstruos, The Adventures of Lumen N. There’s an energy that I haven’t seen recently and I hope that we get to see more comics, more genres, more styles, more approaches.

On occasion, the comic featured excerpts form The Shade’s Journal. Rereading them today, I still enjoy them. Robinson knows 19th Century British literature. I always thought that DC should have published a square bound one shot collecting the stories along with some spot illustrations. Maybe I’m the only one, but I hope that one day I will read a James Robinson novel.

***

The final issue of the series, #80, is dated August 2001.

I think that’s too heavy handed a metaphor.

According to the Internet, the issue showed up on stands June 13. I graduated that spring. Another heavy-handed metaphor. Another reason why the series resonates. Belonging to an age before adulthood and responsibility and all that that entails. When everything in front of me was possibility and potential.

The first issue of the comic ended with Jack having narrowly escaping death. His brother dead, his father in the hospital, he was trapped in someone else’s story. The series concludes with him choosing life and beginning to write his own.

***

The Oscar Wilde quotation that gives these essays its name, that was used for the promotional material, that is perhaps Wilde's most quoted line, comes from the play Lady Windermeyer’s Fan.

The play is a comedy about societal expectations, Victorian/Edwardian customs and behaviors, and one character who seems to be having an affair with a married man, but he's in fact spending time with the woman because she’s his wife’s mother! Unknown family members and secrets and social expectations are classic elements, and when done well, a great source of comedy. This kind of absurd family comedy coupled with the very proper and stuffy pretense that was inherent in Victorian society, is one of the things Wilde enjoyed poking at. In fiction, on stage, and in life.

The quotation itself though is not a grand pronouncement about human nature, which is how it is often portrayed. Instead it is a comment made during a conversation between men about how they behave and are expected to behave towards women. In the context of the play it come off very differently. When I saw it on stage, it made rethink how often I’ve used it and seen it used over the years.

Or maybe not. After all, his point is that we need to try to be better, be more, to attempt to behave in an upstanding way, even if we fall short constantly. Try again, fail again, fail better, as Samuel Beckett put it.

The play is also the source of another of Wilde’s great lines: “Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes.”

***

Comics get looked down upon. There remains a part of me that believes I have wasted what little talent I have writing drivel about mediocre work that will be forgotten the next day for internet writing wages.33 That I should have been writing about William Stafford, or translating poetry, or compiling oral histories, or a dozen other things. I can’t say that it’s helped my depression, my suicidal ideation, my floundering mental health. I may have dealt with all that differently than “James Robinson” does in Airboy, but I haven’t dealt with better. Or come to any conclusions.

While I think the distinction between high art and low art is mostly pretentious nonsense, I believe that certain things are more important than others. Visit Notre Dame de Paris or the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Spend time at The Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Getty Villa or the Tate Britain. Listen to Mozart or Bach. We are surrounded by beauty. Yet we mostly subside on a cultural diet of the middlebrow, at best. Or midcult, as Dwight Macdonald would argue.34

I’ve never found a good definition of art or beauty. Examples abound, but a definition? Roger Scruton35 wrote a lot about beauty that I nod along with in agreement, but it never quite feels true. When I read Scruton, I’ll agree with him and then he’ll often go out of his way to attack other work, other artists, other approaches. Which might say something about the reactionary nature of his politics. I think plenty of things are bad or mediocre, but if you can find God in the ocean or the desert, then you can find God in a puddle or a sandbox.

Starman remains a part of me. It shaped my brain. I’m not alone in this. There is a reason that this comic is one that so many of us have remembered and carried a part of it with us forward in our lives. I hope that Robinson knows that. For all his thoughts and concerns about his career, I hope that he knows that he made a unique and singular work. Not just something that we read, but that we felt. That meant something to us. That has stayed with us after all this time. Something that we know, and that is our own.

***

In 2010’s The Blackest Night crossover, as I understand it, a lot of characters came back as zombies,36 DC’s idea was to revive series that had ended for a special issue, which is honestly a clever concept. Robinson made an 81st issue of Starman with Fernando Dagnino and Bill Sienkiewicz.

I wish I could say that I liked it. I enjoyed the second Shade series that Robinson made with a team of artists in 2011-12, even if I didn't love it. The Blackest Night issue felt empty. In terms of story and just having a point. The equivalent of drinking espresso, swallowing uppers, cranking the volume to 11, and hoping the next day that you’ll realize you improvised some genius riff instead of simply making noise. Maybe reviving a dead thing and ultimately making something empty is a good a description of the whole miniseries and crossover event. I don’t know.

At the end of the special issue, I was reminded of issue #80, which I assume was intentional. It ends with love. Maybe more tenuous and uncertain than the note that the series closed on, but 2010, with ongoing wars and the world still dealing with the fallout from the global recession, was a tenuous and uncertain time. Maybe that’s the best we can hope for. Even for those of us too broken and incapable of it. That’s how the series ended. Love and hope and possibility of change and a new tomorrow. I am tempted to write that it may be the most radical act of imagination that we can manage right now. The truth is, it is always the most radical act of imagination of which we are ever capable.37

The post We are all in the gutter: <i>Starman</i> at 30, part 2 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment