Once upon a time a company called Marvel Comics actually published all kinds of comics. Today they pretty much only publish superhero comics, and even within that narrow margin they narrow things even further by mostly publishing works aimed at their already existing crowd1. It wasn’t always like this. Even after the company was reinvented in the 1960s — the house (of ideas) that Fantastic Four built — they kept publishing war comics, monster comics, humor comics, etc. All part and parcel of the Martin Goodman strategy — throw as much shit against the wall as possible and hope that some of it sticks. Most of that shit was … well, shit. But some of it was the shit, and thus made for pretty good comics.

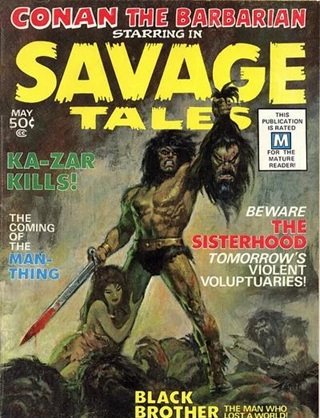

This sort of publishing strategy kept going for several decades, even as more and more of these diverse-genre work found themselves as part of the sludge that is "the Marvel universe." Horror series such as Tomb of Dracula (1972-1979) and The Frankenstein Monster (1973-1975) mostly had their own, self-contained stories, but there was always the danger of Spider-Man popping up. Same with the martial-art/spy adventure series Master of Kung Fu (1974-1983). Meanwhile, the mighty Conan the Barbarian (1970-1993) kept sword and sorcery alive for a good long while. So popular was the Conan title that it became a franchise (King Conan, Red Sonja, Giant-Size Conan). Conan led to the launch of Savage Tales (1971-19752), Marvel’s first successful attempt at doing a black-and-white "comics magazine" in the style of Warren's Creepy and Eerie. That volume of Savage Tales featured adventure-style comics (Conan, Kull, Brak) and some horror stuff (first appearance of Man-Thing), which harkened back to the pre-comics pulps. In its wake: Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, Tales of the Zombie, Planet of the Apes, Savage Sword of Conan (easily the most successful) and many others.

Enter Larry Hama. In the 1980s, Hama, already an editor on several non-superhero stuff at Marvel (including the aforementioned Savage Sword of Conan)3 proposed a new take on Savage Tales, one that would still appeal to the same audience of violence-loving teens. Instead of fantasy Hama wanted something more grounded, a return to the world of an EC-style action anthology. Specifically, the kind of stuff that ran in Two-Fisted Tales (compared to the more grim Frontline Combat), full of historically-accurate weapon reproductions and as much blood and guts as management would allow. According to Hama they basically let him do whatever he wanted with the new Savage Tales … which sank like a stone after eight (oversized) issues. There was no room for Savage Tales at Marvel then, there is certainly no room for it now.

Which is why I am quite thankful Fantagraphics decided to reprint the whole series in one hefty volume as part of their Lost Marvels reprint series. Between Lost Marvels and The Atlas Library one can certainly say Fantagraphics take better care of Marvel’s legacy than Marvel themselves. I am expecting a deluxe collection of Marvel’s Alf comics in the near future. With all due respect for Tower of Shadows 4 and Phantom Eagle 5 this is the stuff I’ve been waiting for — 500-plus pages of blood, sweat and tears illustrated by the likes of Michael Golden, Herb Trimpe, Sam Glanzman and John Severin.

Severin, by the way, is the most prolific artist here — the only one to draw a story in every issue (in some he draws two ). Severin is emblematic of this new Savage Tales, for both good and ill. Good because Severin was a fantastic artist6 on this type of story, having formulated his style in the trenches of EC three decades before the first issue of Savage Tales saw the light of day. Ill because Severin drew exactly these kinds of stories three decades ago. More than one short here seems like it could’ve been found in a safe with William M. Gaines' name on it, including the particular type of title lettering and the overabundance of caption boxes. Savage Tales was meant to be the cutting edge of 1985, not 1955. Archie Goodwin, a name that also appears in this collection and whose spirit seemingly guides the enterprise as a whole, did more risqué stuff with Blazing Combat — a work that came out in the 1960s!

The covers, all painted babes in arms, seem to promise a Heavy Metal-style rush; yet the insides of the comics are surprisingly chaste. The few women here are victims to be saved, lost Lenores to mourned or femme fatales to tempt the heroes off the beaten path. That is, when you even see them — most of the stories are in the boys-only mold. Less than their contemporaries, the stories here reminded me of the stuff you used to find in Action7 (that’s the British magazine, not the one with Superman). This is a "man’s world," which means there is simply no room for women, and just a glance at the creative credits would this abundantly clear. Not even as objects of lust, make your own judgment whether it is better or worse. Which isn’t to say Savage Tales is bad, but is decidedly retrograde. It was retro when it came out and is even more retro today. Some might say it goes so further back that it becomes forward looking … not me though. I enjoy the stuff it emulates, and so I enjoy Savage Tales. On that level, the surface level, it works exactly as you want it to.

None of it would be possible without the right artists. They are clearly expected to do most of the heavy lifting, with the stories either being (at worst) excuses to present the violence necessary to satisfy us or (at best) vehicles for the sort "what a cruel twist of fate" that populated Creepy in its early years: You do bad things, bad things happen to you. While Hama’s introduction speaks of an attempt to present a more grounded storytelling based on real history, several of the ongoing strips (the magazine ditched them as it went along, the last two issues being composed mostly of one-off stories) take place in post-apocalyptic futures.

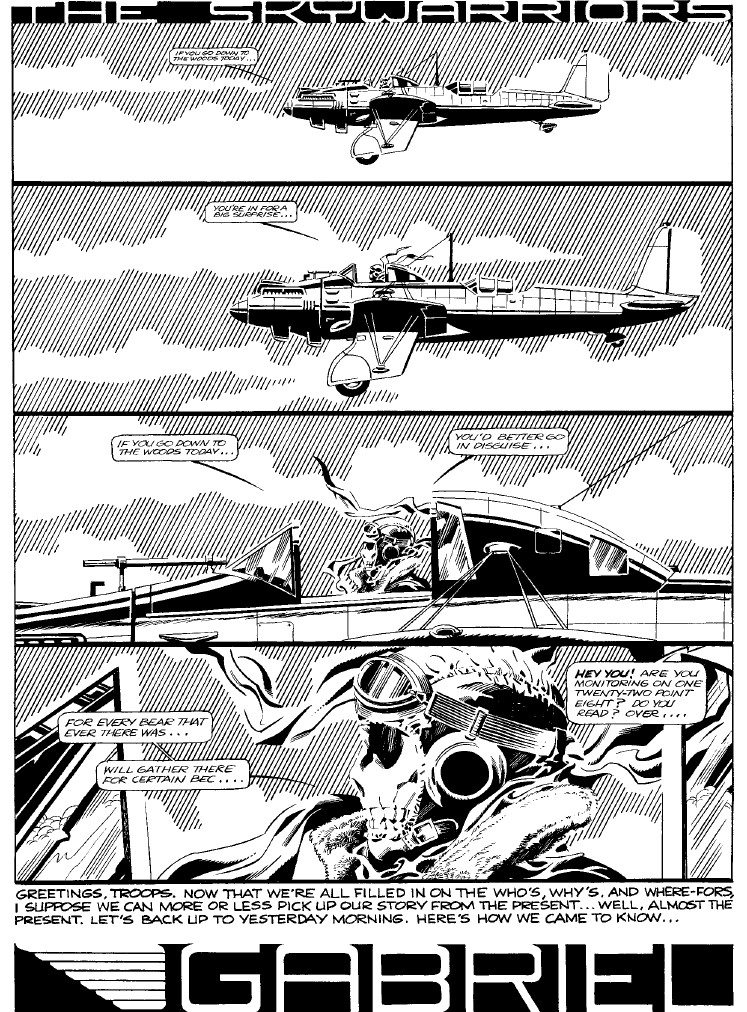

Herb Trimpe’s Skywarriors, a work that seemed like it could have been drawn by Caniff, gives us a post-American world, in which most advanced weapons got scrapped … as good excuse as any for his Flying Tigers-esqe protagonists to literally break out the museum pieces, with pre-WWII airplanes. "Excuse" is the operative word here. There isn’t much of a reason for a strip to happen other than Trimpe’s desire to draw that kind of stuff and (probably) not wanting to bother about doing proper historical research. The actual plots of the four Skywarriors stories manage to be both overdone (in terms of histrionics) and underwritten (in terms of character motivation). Not that it matters — it looks fantastic. I always liked Trimpe in his cartoon-comedy mode, in his toy-selling mode and even his odd attempt at emulating Rob Liefeld had a (small) sort of charm to it. But seeing him going full-classic comic strip in black and white shows what a whole new side of him as an artist. If nothing else Savage Tales tells you a tale about how savage the comics industry is, how it plugs some very talented people into the role of muzak composers, when a little Mozart exists in their fingertips.

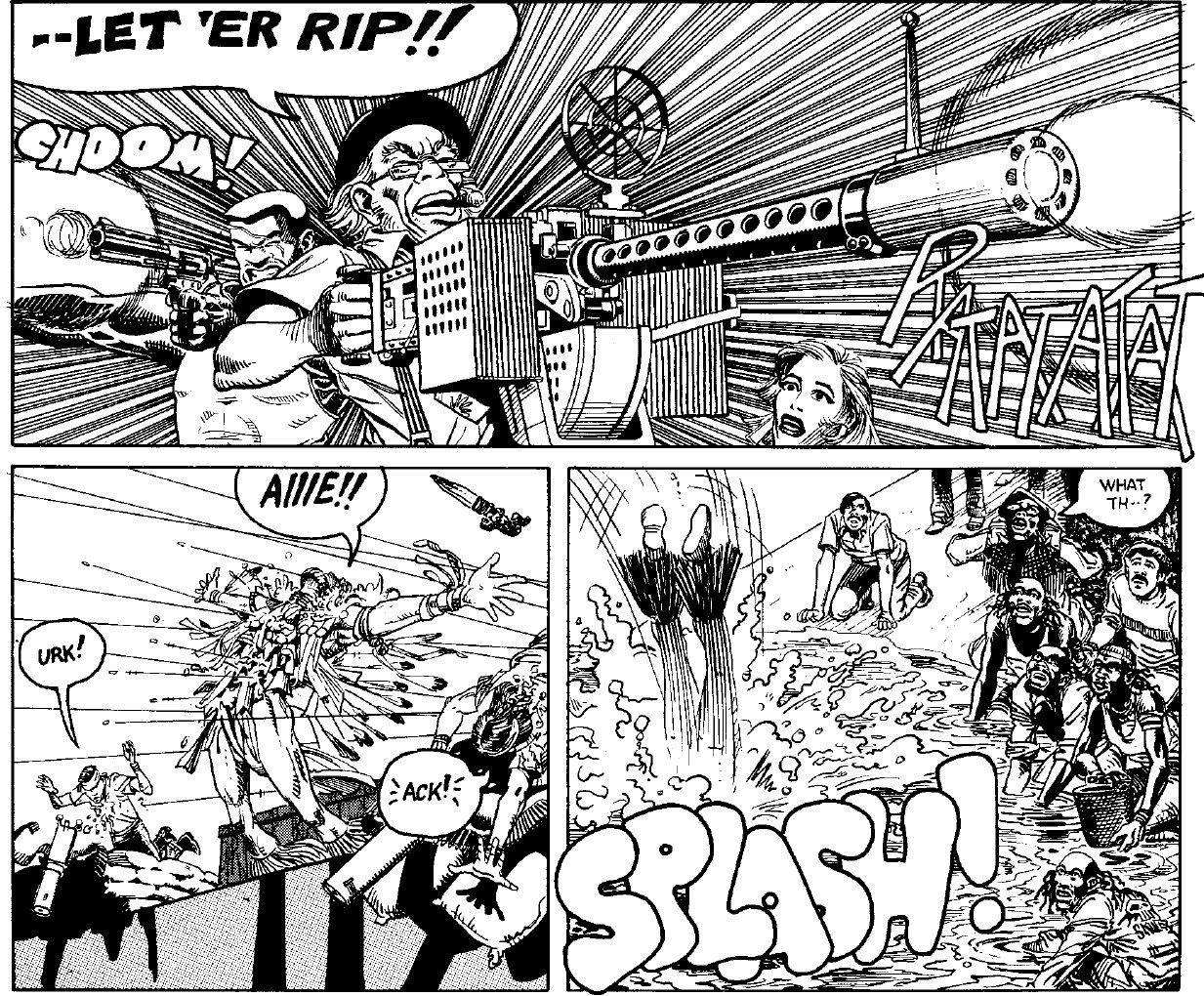

A different sort of post-apocalyptic reality can be found in "Blood and Gutz," an odd-couple action story featuring a hulking African-American and aging Jewish-American shooter (and their two girlfriends) having all sorts of wacky adventures. Both words and pictures here are by Will Jungkuntz. A skilled and stylized artist, sadly these four shorts represent a good fifty precent of his career. Jungkuntz died tragically young, and while the writing is oft on the wrong side of broad (Blood’s dialogue does one of these phonetic accents that tend to be very annoying in comics) the actual cartooning is unimpeachable. The first strip, involving going out to get a pizza with seemingly the entire city standing in his way, is the sort of comedic exaggeration of violence worthy of Judge Dredd. Jungkuntz is possibly the one talent here that actually feels ‘of his time’ rather than playing in retro mode.

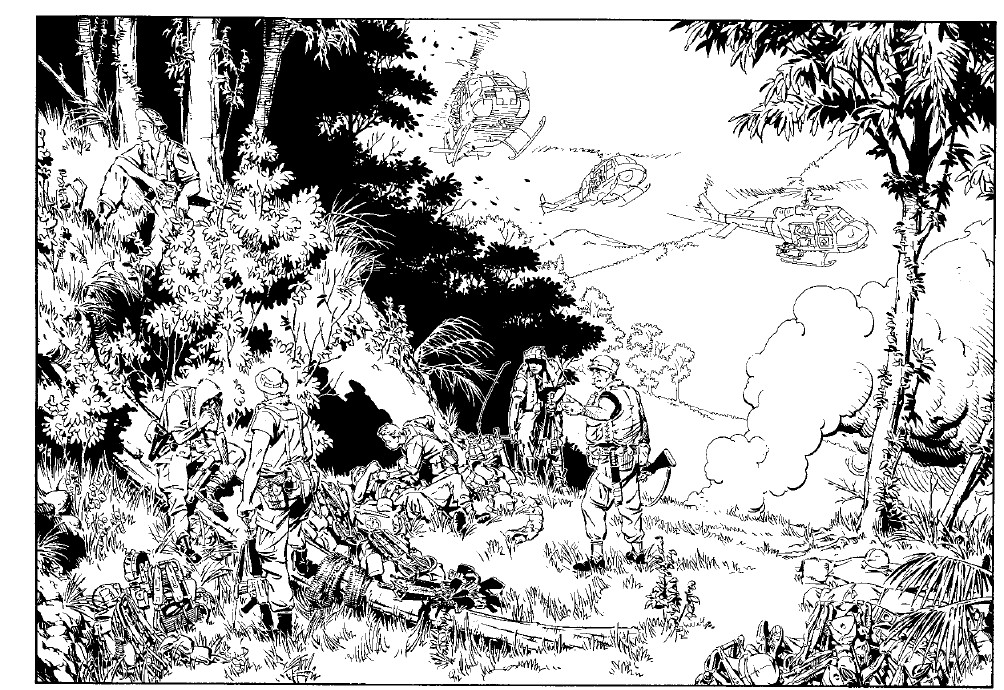

Other continuity strips include "Good ol’ Boys,” a generic moonshiner mob story. John Arcudi scripts a short burst of "Skullhunter" stories that take the Lone Wolf and Cub formula to the American underworld a decade ahead of Road to Perdition; these suffer most from the backwards-looking style of the project, you can see these stories wanting to be gorier than they are allowed to be. At least Vincent Waller seems to be having fun drawing them. “5th to the 1st” by Doug Murray and Michael Golden isn’t so much an ongoing strip as a series of shorts focusing on the Vietnam War, with the creative team soon switching to the ongoing war series The ‘Nam 8. “5th to the 1st” isn’t very good as a story; it's a collection of incidents without much character to its, well, characters, but it is recognized as the type of thing Savage Tales was trying to be, and also a bit closer to Frontline Combat in spirit

One must also mention that most prolific writer in the series, one “Charles Dixon,” nowadays more known as Chuck Dixon. Once the most mainstream of mainstream writers, he was all over DC in the 1990s. Today a contributor for something called Rippaverse Comics, a company founded by a rap-metal singing YouTuber. This man used to work with Brian Stelfreeze and Marcos Martin. He had stories drawn by the mighty Jorge Zaffino. It’s a long drop. Still, it is little surprise that younger Dixon easily found himself within the pages of Savage Tales, whose old-school creative ideology fitted his old-school political outlook. Every script by him in this collection reads like a man who wears a 10-gallon hat, even in winter.

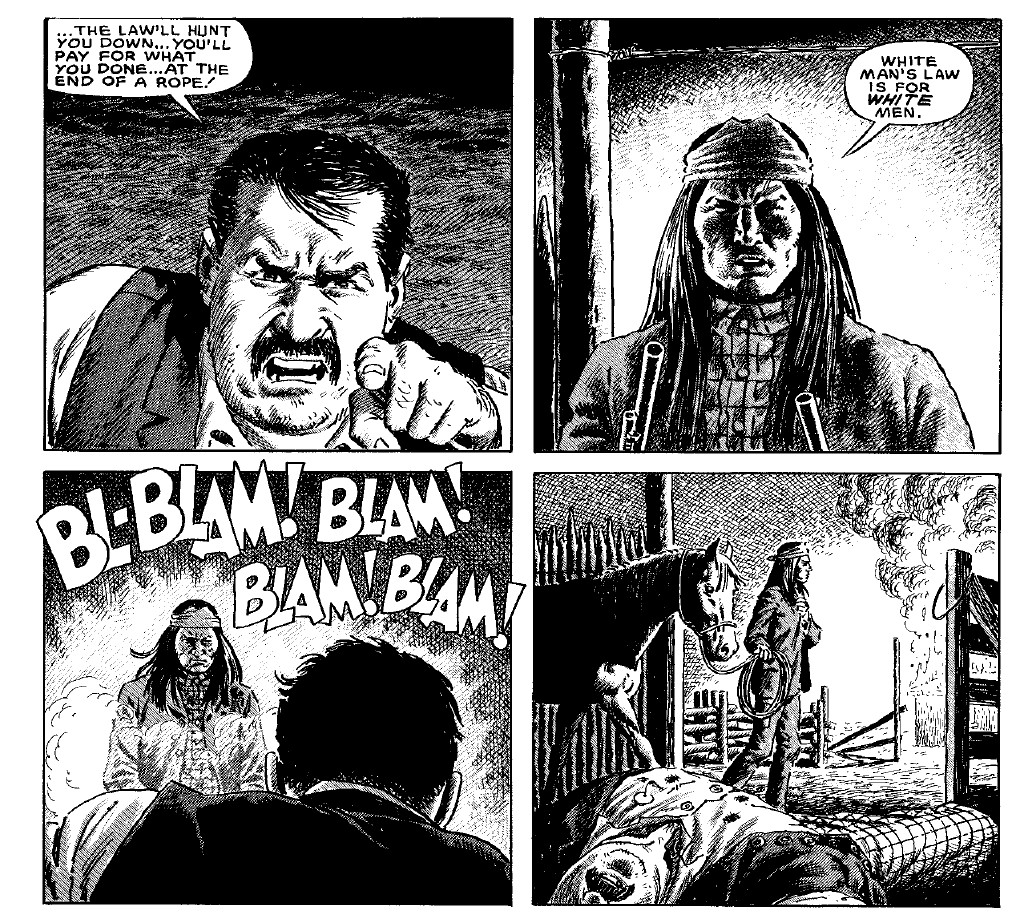

This isn’t to say Savage Tales is a "conservative" book in the modern-day political sense, the frothing-at-the-mouth-America-first sense. Rather, it is conservative in the Teddy Roosevelt sense. The stories Dixon writes here are all cowboy clichés about the one brave man against the system, and it doesn’t really matter what the system represents. In “The Stray” (by Dixon and Severin) a Native American rancher takes righteous vengeance against a white man who stole his cattle, spitting that “White man’s law is for white man.” The celebration is mostly of individual heroics, and personal honor can be achieved no matter what side one is fighting for. In “The Canyon of the Three” the haughty cavalry-officer chasing Apache rebels is sure of his victory by the right of superior numbers, technology and (unwritten) culture, but the brave and clever Geronimo gets one over him and the story is particularly giddy in the Apache’s victory — the underdog always wins the most important thing (his honor).

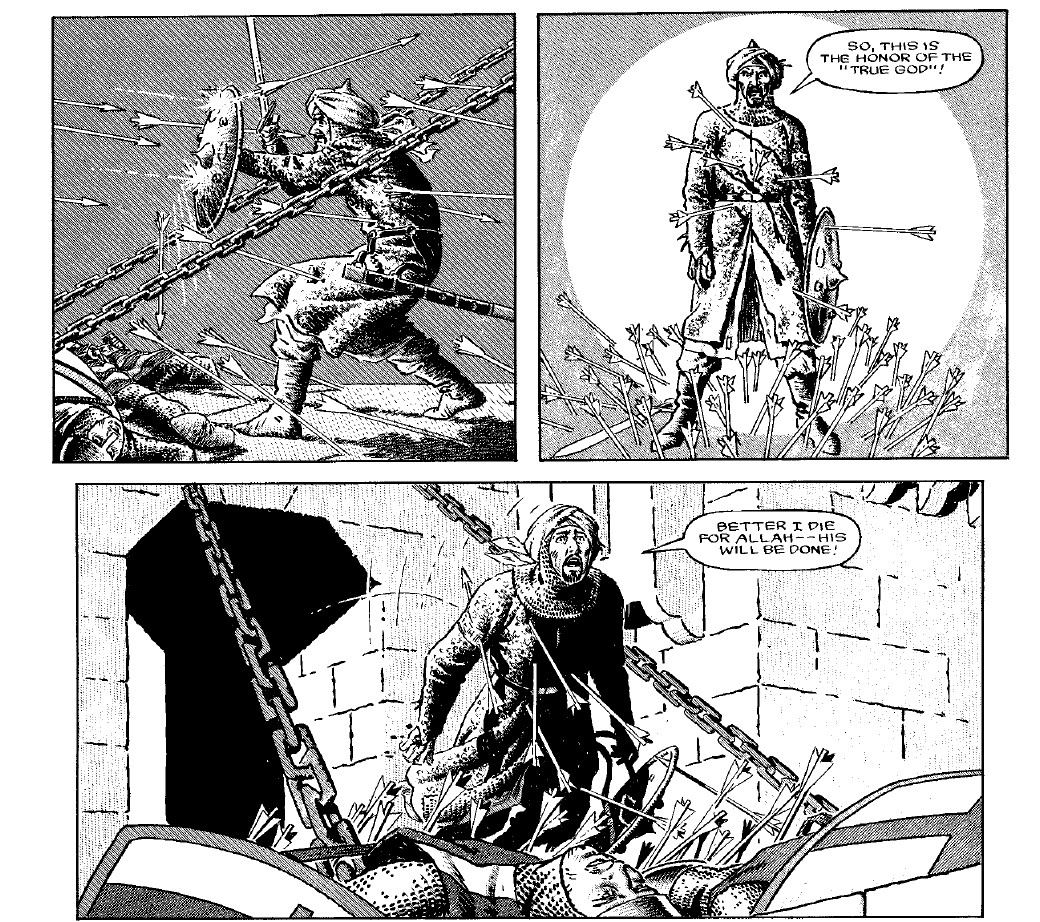

Savage Tales’ overall ideology is most directly expressed in “A Question of Honor” (by Douglas Murray and John Severin), which sees a single Scarcen (Muslim) warrior holding a long group of Chrisitan knights at bay, while pleading with the Christian commander to fight him in a single battle and spare the bloodshed. The Commander does the tactically smart thing, telling his people to use their weight of numbers and arrows to take down his enemy, but it is also the dishonorable thing, and thus verboten. The Scarcen warrior dies an honorable death and the Christian knights turn against their leader until he redeems himself by committing a suicidal charge against the fortress and dying like a pincushion. The evil in this story is all in the behavior of individual people (a single man), the question of the Crusade itself, justifying this war of conquest, is never brought up.

Though the majority of stories play up these notions of old-fashioned machismo not all of them are like that. Pepe Moreno’s “War Zone” is a rare story focusing on a modern-day conflict, the cold war, when a series of mistakes in a war game taking place on the East-West German border becomes a deadly exercise in live fire. It’s not the best story in the trade, though it is certainly one of the best-looking, but it is a story of no heroics, nor even of honor. The mistakes leading to the fire exchange are all plausible, nothing is achieved and little is learned.

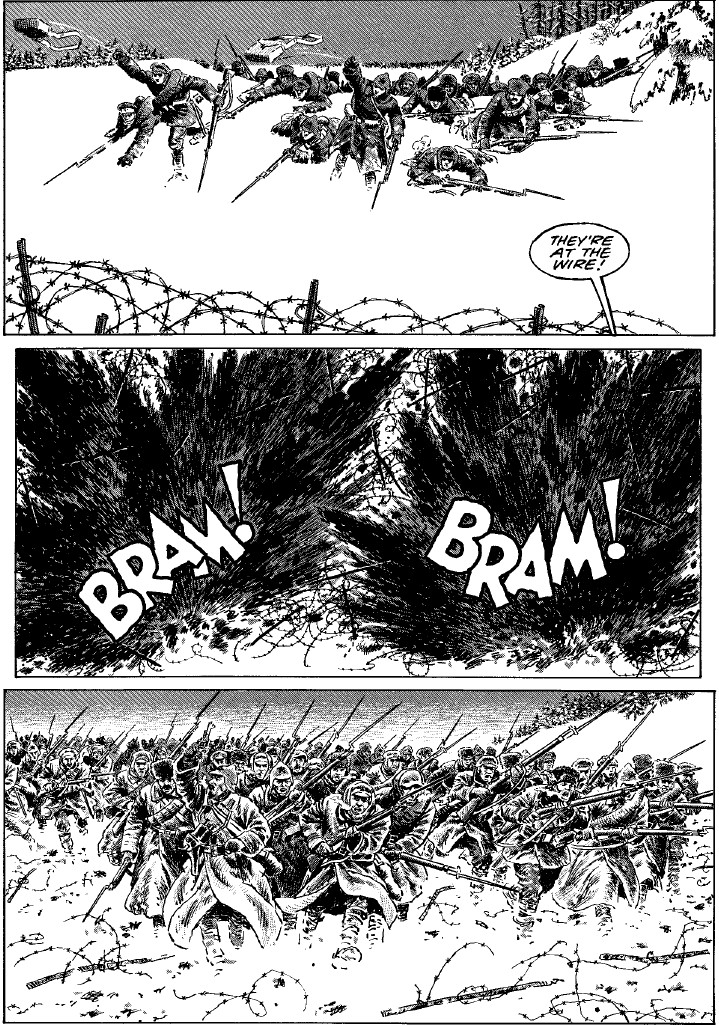

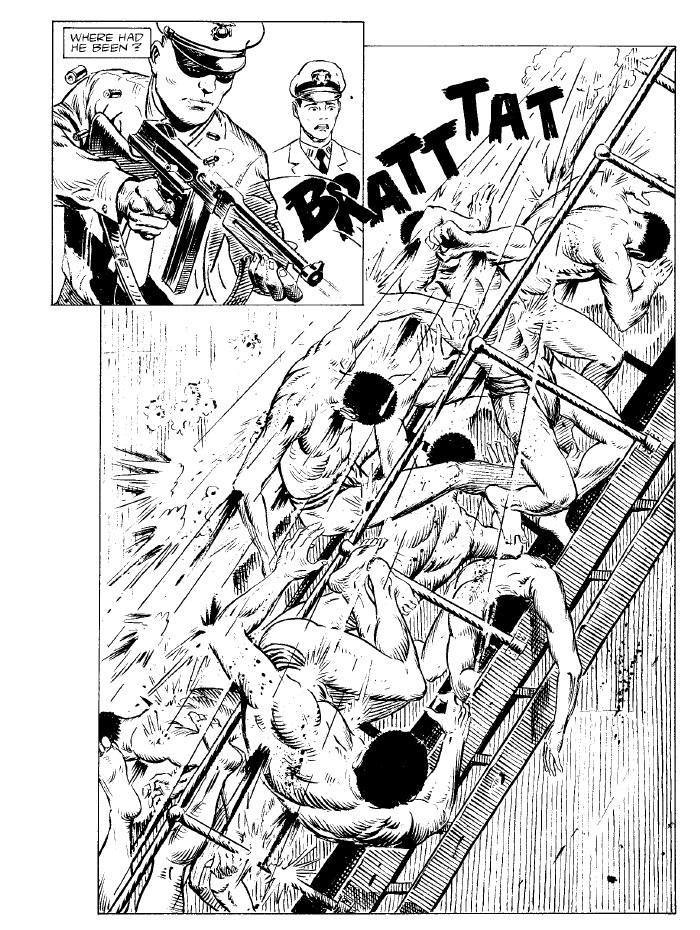

The other standouts are the three unwieldy named tales “War and Peace – Tales by Mas,” all written and drawn by Sam Glanzman (of Sailor’s Story and The Lonely War of Capt. Willy Schultz fame). I haven’t, despite admitted fondness for war comics, read any work by Glanzman; something that should be fixed tout de suite. I have mentioned (in my soon-to be-published review of Corto Maltese) that there are rare works that exist comfortably within the confines of "genre" and still manage, through that alchemy of words and pictures, to produce something that I would call "literary"; a sort of innate truth-in-art that seems impossible to achieve through funny pictures of people shooting at each other9. It is there in “Trinity,” a story detailing a Marine guard, possibly suffering PTSD, executing prisoners of war and committing suicide. Sure, the grimness of the subject gives it gravitas, but it would not suffice alone. It is in Glanzman's choices of how tell the story, the wondering mind of an old man trying to make sense of something he knows cannot make sense, that the quality is found. It is also how his pen and pencil, incredibly soft here, delineate human bodies rattled as bullets pierce them from above; the unfathomable last gaze of the soldier looking at us before he puts the gun to his head.

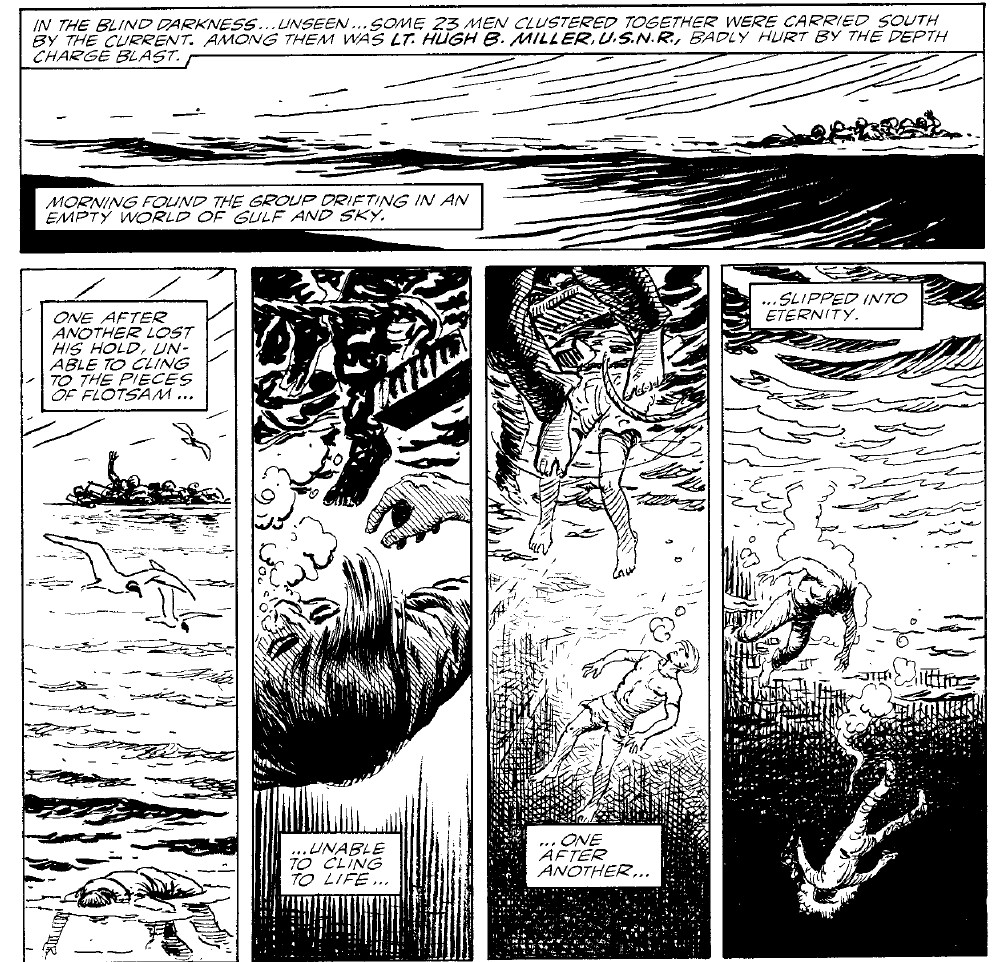

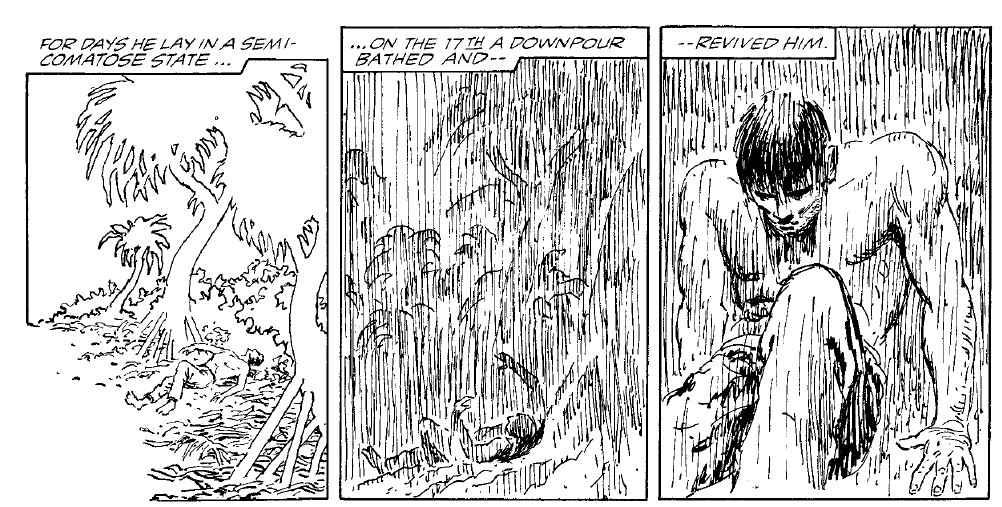

As if to prove it is not just the grimness of it all that gives him quality, the more lighthearted “Rescued by Luck” (based on a true story), contains a simple three-panel scene showing the other way around — a man close to death slowly reviving. Glazman does not press the point, he draws a man reborn, from a cradle of mud into a new life. The first panel is halfway in the afterlife and our man crawls through it back to corporeal reality, where pen and pencil give him full detailed form. Death and life intertwine in these stories, and it is not only the personal heroics and physical capability on the individuals that save them. Our man is later saved by luck (the reason for the title is both silly and endearing, the kind of thing that would be corny in any other hand but Glanzman's).

Galnzman’s stories are the best of the lot. Sadly, they are also a sign of what Savage Tales could have been. It is always lovely to look at. However, only on the rare occasions when it is unafraid to look directly into the face of war, rather than resurrecting clichés that were old-hat when Severin was still a young man, does Savage Tales become more than a well-crafted tribute to the past. Savage Tales as a series, as a collection, is a thing of beauty that occasionally remembers it can be art.

The post <i>Lost Marvels Volume 3: Savage Tales</i>: Old-fashioned machismo in the EC tradition appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment