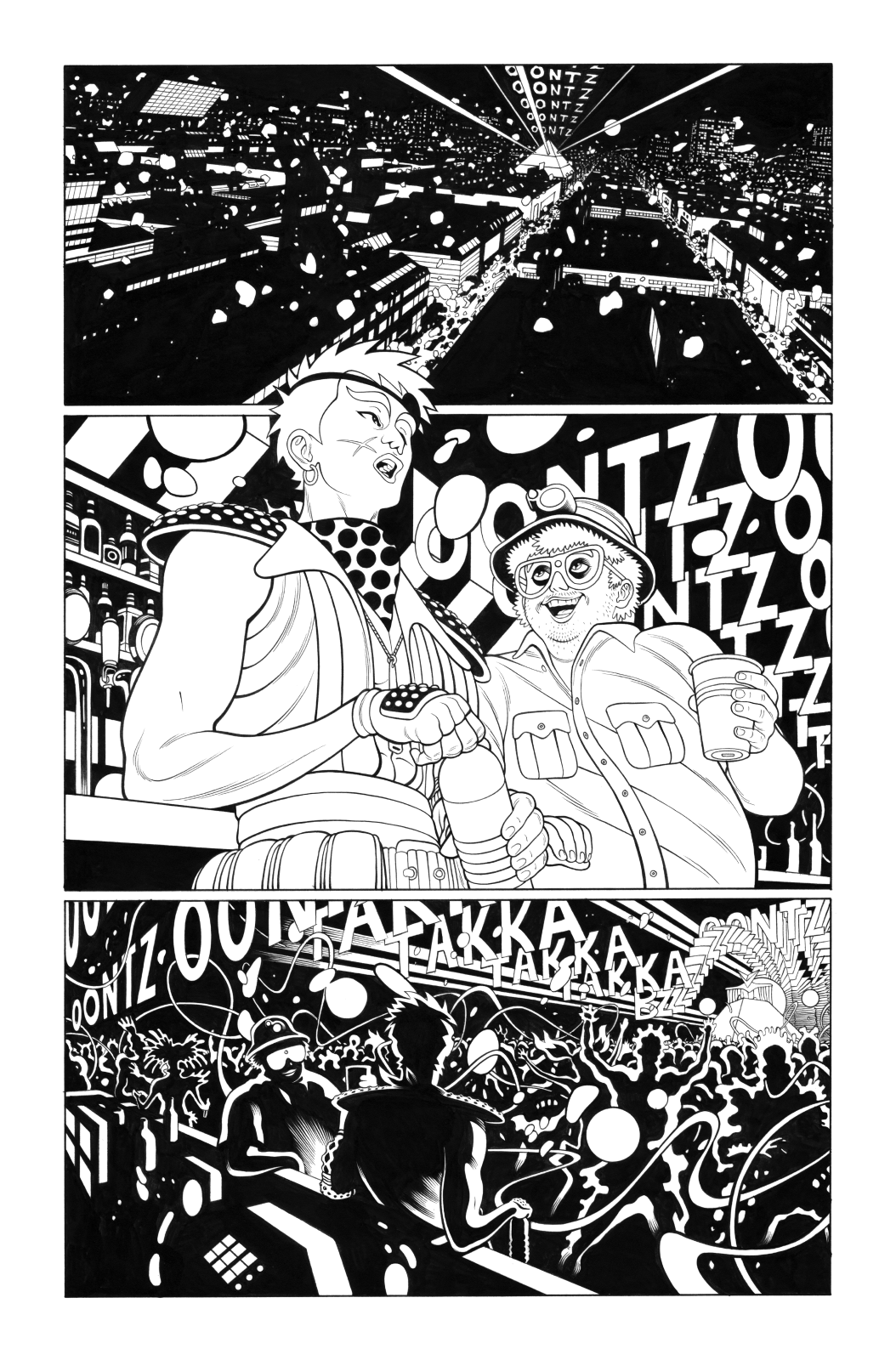

A Tradd Moore drawing can be an object lesson in the limits of perception. Our senses report no warp and weft to perspective, show no trace of the transmundane realities that might elude human faculties of detection. Moore’s artwork gestures towards a world only glimpsed briefly by the boldest of hallucinogenic experiments—indeed, it is hardly uncommon to turn a comic book illustrated by Moore repeatedly along its spine just to find one’s bearings.

A graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design and a Georgia native, Moore’s first published work was The Strange Talent of Luther Strode (Image, 2011-12) with writer Justin Jordan. The story of a teenage boy gaining superhuman fighting abilities from an esoteric exercise manual made optimal use of Moore’s talents, whose artistic calling cards—a draftsman’s facility with detail and a willingness to experiment with curvilinear perspectives—soon became well-known among readers.

Strode allowed Moore to leave his imprint on household comic properties, including brief stints on DC’s Legends of the Dark Knight (#8, 2013) and Marvel’s All-New Ghost Rider (#1-5, 2014) and Venom (#150, 2017). His landmark run on Silver Surfer: Black (2019) with writer Donny Cates premiered an evolved art style, which became more fluid and evocative of the American psychedelic comics tradition made famous by the likes of Victor Moscoso, Robert Williams, Paul Kirchner, or Lale Westvind.

Silver Surfer: Black soon garnered Moore attention from broader corners of the creative world, leading to poster design work for Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 film of Dune and a Warner Bros. film option of his anti-authoritarian comic book The New World (Image, 2018) co-created with Aleš Kot.

Next month, a special Treasury Edition collection of Moore’s latest project, Doctor Strange: Fall Sunrise, will arrive in bookstores. A ruminative, metaphysical journey through the farthest reaches of the Marvel Comics universe, the book catapulted the Sorcerer Supreme into a phantasmagorical nightmare unlike anything the character had endured in his 50-year history, and saw Moore writing for himself.

I corresponded with Moore to discuss the tension between abstraction and formal craft in his work, the question of whether he will ever work with writers again, and his belief that AI-generated art will not have a lasting impact on the comics industry.

-Jean Marc Ah-Sen

JEAN MARC AH-SEN: Doctor Strange: Fall Sunrise seems to be a book that your entire career has been building up to. There is more detail, visual experimentation and risk-taking in this book than in anything you have done before. In a career already defined by those qualities, I think that is saying a lot. Before you started the project, did you know that you wanted to push these limits to new extremes? Do you feel that this outlook is an integral component to your evolution as an artist?

TRADD MOORE: Thank you so much! I’m always trying to surpass or shed my skin in some way. Every project is an exercise in new extremes—if I’m not touching the sun or clawing the earth, I’ll tear at my face. I have to move. Forward-up-down-wherever, I don’t care—let’s just go, you know?

Wild passions cry out: for growth, for expression, for excellence. Curiosity, and yearning and ambition and… I don’t always know what for, but I mostly love it. It’s a lot. There’s just this compulsive motivation to sprint. PUSH! Push FURTHER!

Tall mountains to climb; they’re the best, aren’t they?

So yeah, pursuing fascinations with art and confronting the questions they present is how I like to examine life and the world. It’s one of my favorite ways to explore, learn, and communicate. Making art helps me feel connected to humanity and history. It’s purposeful—it gets me up in the morning. I don’t know what else to do. I need some kind of pressure. The moment I think, “Dang, I don’t know if I can pull this off,” I know that’s exactly what I’ll be attempting.

While you co-plotted The New World with co-creator Aleš Kot, I believe that you took on writing duties for the first time in your career with Fall Sunrise. How long have your harbored ambitions to write and draw your own comics? Did it simplify the drawing process because there were hardly any impediments to interpreting the intentions of a writer’s script with fidelity?

Fall Sunrise is indeed the first time I’ve written a full series (I’ve written and drawn some single issues and shorts before), and YES, writing and drawing my own comics has always been the vision!

I remember reading Will Eisner, Frank Miller, and Barry Windsor-Smith comics growing up and thinking, “THIS! This is what I want to do!” I always return to their work when I need that fire in me.

I co-plotted/co-developed the stories of Silver Surfer: Black with Donny Cates, The Legacy of Luther Strode with Justin Jordan, and The New World with Aleš Kot, but the scripts were all theirs. It’s hard to describe how collaborative comics work is without sounding labored and boring, so suffice it to say: very.

—

Bear with me on a tangent, will you?

I struggle to share certain feelings in conversation—I worry about talking too much (I’m doing it now!), or hurting someone’s feelings, or spitting out some stupid fucking half-formed thoughts, or being rude, or pointless, or contrarian, or annoyingly nihilistic. I don’t want to bring anyone down. So in conversation, I tend to focus my efforts on being encouraging and positive—which I love doing—but it’s of course not the whole picture.

In art and literature—I won’t say it’s easier to communicate there—but I’m more comfortable working through ideas and feelings in their fullness in that quiet, isolated space. The harrowing lows, the impossible heights; the terror, the angst, the loathing, the love. The confusion! All these things; every tenuous little thread. It’s not the point to find answers—often the opposite—but rather to develop and lay out a full thought.

A person can express themselves abstractly in art, which feels like home. I feel most at peace and most myself when I’m not talking and not trying to make sense of anything.

—

Coming back to the question: all that to say, while I cherish the work experiences I’ve had, ultimately—to me—my previous comics are the stories of the writers I worked with.

That’s not devaluing my role or the role of the comic artist in general—I visually told the tales; I designed, choreographed, directed, interpreted, adapted, yeah, yeah, yeah, all that. The comics are certainly “mine” in a lot of ways. I have equal ownership, agency, voice, and partnership there. I’ve explored personal visions within the narratives, but if the words aren’t my words, the narrative is not my narrative. How could it be? Perhaps more honestly, I don’t want it to be. How can your words express my intent? Swine! Pretender! Begone! I share not my soul with YOU! I share not my soul with ANYONE!

But maybe I’m too “all or nothing” in general (yeah, yeah, shut up, I’m working on it). I take it all back! (No, I don’t.)

Again, I’m not speaking on the art form or industry at large here—I often feel the opposite of everything I just said when I’m talking about artists whose work I love and stand for—just my thoughts on my own work. It doesn’t feel like mine to me unless I wrote it.

Thus, Fall Sunrise is the first series in my professional career that feels like MINE—sorry Ditko, I stole your boy for a minute—and it’s a nice thing. I’m really grateful for the opportunity and space I was granted here. Hurrah!

As with other creators who have made this creative leap, have readers seen the end to your collaborations with other writers? Will future books see you exercising complete creative control over the writing and drawing of your projects?

On working with other writers—I won’t draw a hard line and say, “NEVER AGAIN!” but I’ll draw a soft line and say, “NEVER AGAIN!”

Aha! Fuck all you other writers!

Yeah, YOU!

For real though, I don’t know how I’m going to feel in 14 minutes, much less how I’ll feel in a year or two. Who can say? Right now, I’m loving doing things myself, so I’m going to keep doing that. I’d like to push it further in upcoming projects.

How did writing and drawing the book affect its pacing and structure? There are times when you deliberately control the flow of the story by increasing or decreasing the number of panels, captions, and dialogue in a scene. This temporal aspect of how a comic is read has always been an essential component of the art form, but it seems that this was a formal quality that you especially wanted to foreground.

Yes, absolutely! I like to foreground formal comics craft and art techniques in my work and use their development and deconstruction as part of the holistic narrative. The temporal aspect of sequential storytelling is the essential component of the craft, and thus one of my favorite things to play with. Whether that involves experimenting with odd panel counts & layouts, dismantling page structures, or breaking down line work itself, it’s all part of the story being told.

I think that often we (artists, readers, people) perceive separations that maybe don’t initially exist, but we create them by acting as if they do—we make enemies of concepts that aren’t in opposition.

Formal Craft vs. Abstraction, for example—they’re not enemies! Sometimes work that prioritizes formal craft and representational imagery is critiqued by one group as lifeless and boring, and abstract expression is critiqued by another as drivel (“My kid could do that,” said the fellow who never learned to draw), but formal craft and abstraction don’t stand in opposition—they’re pieces of the same bigger thing. They contrast and inform one another—left hand, right hand, they’re both your body. The more you learn about formal craft and drawing techniques, the more expressive you can be with your art, and the more effectively you can depict and abstract your thoughts and feelings on the page.

A beautiful thing about comics is that, at their best, everything is one thing. The whole book is the art, not just the drawings, or the plot, or the prose, or the poetry, but the complete work. The ideas, the words themselves, the balloons & caption boxes, the drawings, the gutters, the formatting, ALL OF IT. It’s all one structure, and every choice dictates how the story is perceived. When you’re writing and drawing yourself, it gives you more singular control of that space.

Even down to tiny things—for example, I made custom page templates for Fall Sunrise because I wanted the page borders to have a certain amount of space to breathe, and the line art is largely left in grayscale rather than thresholded (made pure black and white), so the lines feel softer than the pure black inks of, say, Silver Surfer: Black.

Every visual element elicits a response from the reader, so I like to be intentional with every decision. If someone asks, “Why does this page look like this?” there is a 100% chance I have a reason. It might not be a reasonable reason, but there is intent!

Going back to time in particular, I liken it to music. Simple version: music has tempo, time signatures, and a whole lot of other rules to control time and direct a listener’s attention and emotional responses; comics have panels and visual space to do the same. The emotions our visual choices in comics elicit are not as immediately apparent because, among many reasons, the language of comics is not as ubiquitous, ingrained, and understood within culture as music is, but they work similarly.

If music wants to pump you up, get your blood flowing, or stress you out, it often goes faster and with a whole lot of notes. Thrash! Loud helps, dissonance takes the stress further, and odd signatures throw listeners for a loop and make them feel disoriented. Need to feel peaceful? Slow it doooown. Fewer notes, hold them longer. Comfortable, familiar signatures. Pleasant timbre, soft sounds, nice melody. These aren’t always true, but you get the idea.

All this works with comics, but with panels in place of notes—the push and pull of time is expressed by panel layout, page structure, and drawing technique.

One tool you’ll see me use—it’s one of my go-tos—is I’ll load a page with panels to build tension, usually increasing the panel count in sequence over consecutive pages, using progressively harsher cuts, featuring increasingly disparate imagery, and sometimes getting scratchier and wilder with the lines I’m drawing. Then, when the panels become granular and overwhelming near the point of illegibility, I’ll cut to a BIG spacious panel, often a splash page, as a release—EXPLODE or BREATHE. Soak it all in!

It’s the same idea as a breakdown in metal, punk, and hardcore, or a drop in dance & electronic music. If you’ve ever been to a concert or club, you’ve seen the effect these moments of rising tension and eventual release have on people. It’s the best! So cathartic and fun.

Strangely, using a ton of panels on a page but staying rigorously structured with the layout, can create a sense of slow motion, or no time at all. It reminds me of the feeling of Steve Reich or Philip Glass music—it’s waves of these beautiful repeating patterns and cycles and notes coming at you, and before you know it, you feel like you’re floating.

Frank Quitely is one of my favorite artists when it comes to displaying temporality in comics—every time I read a comic he’s drawn, I learn more about the art form or I’m fascinated by a new question or idea about the craft. I remember reading We3 and Flex Mentallo for the first time when I was young and thinking, “Holy shit, I didn’t know you could do this!” I go back and look at the opening sequence in The Multiversity: Pax Americana—the three-page assassination in reverse—oh, at least 20 times a year. It’s amazing!

Fall Sunrise reimagined the spatial limitations of a two-dimensional comic book as well. Readers have to develop new orientations to perspective, depth, point of view, to say nothing of your experiments with biomorphic forms and multiple planes of action. Can you talk about the sense of grandeur that was created with these investigations in geography and scale?

Thank you again. You are too kind.

Ah, you know, I’ve done plenty of work before where I tried to be as legible and formal with perspective and representational forms as I could. As I mentioned above, craft and fundamentals are important to understand and continually engage with as an artist. When I took life drawing classes back in my teens and twenties, I was pursuing realism and I really liked the result—it’s incredibly satisfying when you nail something for the first time, a hand or an eyeball or something, and you can impress your friends and family with it—but I always found myself manipulating something in a drawing to make the figure look like what I saw in front of me. There’s an ephemeral and intuitively “unreal” quality to that. You have to abstract to make a drawing seem alive, and you will abstract whether you mean to or not. Every artist does. There is no escape!

I remember with The New World, I wanted any person to be able to pick up that book and understand how to read it. With Fall Sunrise, I was like, “Fuck it—strap in, folks! Hop in the boat: I’m your Charon. I’m your Willy Wonka today. You ain’t got no say in this ride!”

My thoughts when making Fall Sunrise were: I’m going to present and depict exactly what moves me, whatever I’m trying to display, to the best of my ability, and I’ll try my absolute best to make it as accessible as I can, but I will not be held back by any strict visual realism. I can’t stomach holding back in art anymore. Life is short. I hold back everywhere else in life, but not in art, goddamnit!

So by warping visual and biomorphic forms, they become emotionally “real” to me. Not by “breaking” them per se—the structure remains intact and secretly legible underneath everything—but rather by twisting and stretching them until they SPEAK! I think it’s called torture? That’s what it feels like to be alive sometimes, right? Pulled in every direction and unable to escape your underlying structure? Metal.

So to access the kind of fantastic grandeur and scale it takes to depict a transcendent journey, you have reach! Where to? I don’t know! Beyond wherever you think is reasonable. You just keep reaching until you die. I was inspired by the pensive and melancholy landscape work of Caspar David Friedrich and the impossibly heavy apocalyptic visions of John Martin. I was also inspired by the weird, wonderful, and vibrantly human city and social environments depicted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in his paintings.

And look, here’s the thing: people are smart. We are! People like to be challenged, and people like to learn—readers, listeners, artists, whatever, all of us. We teach each other and build our cultural languages using art. That’s what I’m trying to do for myself when I’m drawing comics and experimenting with the form, and that’s what I like to read from others.

You developed an elegant cosmology in the book that touches on philosophical concepts of form, potentiality, and actuality, and which effectively serves as a kind of creation myth of the Marvel universe. What was the principal attraction of working on a story with far-reaching metaphysical implications?

Yeah, the philosophical and theological concepts I’m dancing with in Fall Sunrise are precisely why I made the comic! Forms, faith, mothers, fathers, morality, virtue, value, despair, cruelty, acceptance, purpose, and NOTHING, oh God, and there’s NOTHING!

I love metaphysical shit.

I love reading philosophy texts from throughout the ages and being spun around in circles by these wise, angsty wizards. Same as art, it just makes me feel connected to humanity and the universalities of the human experience.

I was reading an assortment of books in 2019-2021—a bunch of philosophy & history books and fantasy novels—and thinking, “Damn, you just can’t go into the same level of intellectual depth on dense subjects like philosophy, politics, religion, economy, etc. in a comic as you can in a book or essay.” It’s not a matter of intelligence, wisdom, and creativity I’m talking about here, it’s about trying to understand the strengths, limitations, and unique qualities of different art forms themselves. Clearly, I ain’t no Socrates, or Plato, or Kierkegaard, or Nietzsche, and even if an artist out there is their intellectual peer (I’m sure you’re out there, philosopher artist! Give my love to da Vinci!), how are you going to draw Beyond Good and Evil or Nicomachean Ethics or something like that? You’re not. What would be the point? They’re already done! Text like that doesn’t work as a narrative comic because those books are not stories. They are exactly and beautifully what they were written to be.

Thus, the response: do something else. What can I do in a comic that expresses and responds to some of these philosophical concepts, but does so in a way that is unique and exclusive to the medium and language of comics? What can I do in this space that perhaps cannot be replicated in another? How many left turns can one take? It won’t be nearly as direct and thorough as the books inspiring me—that’s not the point—but can it perhaps be valuable and beautiful in some altogether different and beguiling way? Like… a painting? Like music! I’m not a philosopher, or a novelist, or a scientist, or an academic; I’m a comic book artist, goddamnit! Let’s make a comic!

So for about a decade, I’ve had ideas floating around in my head and in notepads, but I wasn’t sure how or if they fit together in a narrative, or where I would take the narrative if the ideas coalesced. Once a structure took shape in the form of a cosmology and fantasy narrative—Fall Sunrise—I understood it was something I could develop independently as a creator-owned comic, but I also believed it could work well on a big platform if I wanted it to. You make concessions either way—that’s life—but something kept calling me toward trying to display the story on a large stage. There can be power in that. There is ample room for idiosyncratic art and voices in the mainstream space, and there’s hunger for it, and we see it all the time. May we never take them for granted!

I think it’s a noble endeavor to try to stay true to your values and vision on a highly visible platform such as Marvel or DC or whoever—we all know the big dogs. It’s hard! You gotta tie your fucking feet to the ground, and learn to say, “No.”

Being a good team player is essential in that space, but there’s compromise and there’s compromised, you know? Hard to see the difference when you’re underwater. The willpower and willingness to walk away from a project if the former becomes the latter is a great strength indeed.

With Fall Sunrise, I wanted nothing to do with the Marvel Universe as a whole—that was non-negotiable from the pitch—but I thought that Doctor Strange himself, or the concepts and spirit of what people like to engage with via Strange, would be a fitting protagonist for the narrative. Strange is our POV, and he’s a compelling character with 60 odd years of stories, but I didn’t want any past stories to be necessary or connected. I wanted Fall Sunrise to be new and require no prerequisites. Barry Windsor-Smith’s Weapon X succeeds in that for me, and I love it to death.

Having Doctor Strange as the lead character allowed me to jump straight into the other “newness” I was hungry for. I could step directly into the fun cosmology and existential booby-traps I was balancing on without having to develop a new lead character to take us there, you know? We could hit the ground running following this familiar guide down a new trail.

I remember my foot-in-the-door elevator pitch to Marvel editorial was something along the lines of, “I want to make The Seventh Seal meets Castlevania: Symphony of the Night starring Doctor Strange.” Go, Trojan Horse, Go!

Dracula: “What is a man? A miserable little pile of secrets.”

The projects that you choose to work on tend to explore moral quandaries like the struggle between good and evil, liberty and repression, or the needs of the collective and the individual. Do you look for projects that engage with these themes explicitly? If so, does there need to be a timely urgency to a story in order for you to want to work on it?

One of the beautiful things about comics and other individual art forms or small team creative endeavors—literature, poetry, music, whatever—is that you don’t have to go looking for a project that engages with the themes that interest you; you bring the themes that interest you to anything you work on. The power and urgency is yours, artist! Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Bring the heat to everything you touch!

But yes, it’s important to be explicit and intentional when developing or choosing a project within yourself; with, “What am I trying to say?” What am I trying to discuss or challenge here? Can I answer that? If not, what the hell am I doing? That’s the story. I love genre and camp, but if I’m going to spend years of my life working on something, it needs to be an avenue to express something meaningful to me or to exorcise some repressed devil, not simply for love of an aesthetic. That’s not enough for me anymore.

If I’m looking at a job opportunity and I can’t find some artistic “in”, if I can’t find something personal to explore within the parameters of the assignment, there’s no reason to do it. I think you can usually find your “in” if you dig deep, tie together unexpected threads, and speak from your heart. Your employer may disagree and fire you, but fuck ‘em.

Regarding the urgency and pressing relevance of certain story themes, I try not to overthink that. I do, but I try not to. Of course, you should be cognizant of the climate in which you’re telling stories and mindful of how they can affect people—Who are you speaking to? Who stands to be uplifted or shat upon by your tale?—but it can paralyze you creatively if you get too worried about trying to make a story capital “I” Important. If you’re out here trying to write something that means something to everyone… it ain’t gonna happen. You get a lot of toothless tales and spineless platitudes if you speak too broadly. Feels fake! Plus, you never really know how anything is gonna land with anyone—people are very different.

So I figure creatives should speak honestly on whatever topic feels urgent and pressing to them—anything!—and know for a fact that there are other people in that same place. Heavy or light, sad or joyous, political or philosophical, silly or sincere: there’s a time and place for all sorts of things. Crime and Punishment and Cats both exist.

Be specific! Be incisive! Get personal! Go bleed on that page, hero! That’s art! Say your piece and take what comes.

You have talked about some of the wide-ranging influences that informed Fall Sunrise, which included things like Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, William Blake’s paintings, and the video game Tekken. Do you think that there is a distinction between high and low culture that actually exists? Or are there only aesthetes and gatekeepers who are missing the point?

I think distinctions exist, but they are often misunderstood, misrepresented, and misvalued.

It’s like we were talking about before, if people make distinctions and divisions for whatever reason, they exist. We all know this; we see these distinctions time and again controlling our lives and history. Whether or not these distinctions should exist—whether or not they’re helpful, or hateful, or missing the point—is another thing entirely, but whether or not they do—they do. They’re not real like a rock is, but real like language, or identity, or morality, or law. It’s human-made stuff, and only relevant to us—birds don’t give a fuck about state lines—but real nonetheless.

So art distinctions exist in that way, but look, you can step right through art distinctions. Who cares? Fuck a gatekeeper, and not lovingly. Essentially every notable art movement begins with people walking through or deconstructing invisible (though no less prohibitive) established art barriers and shaking things up, and rarely are these movements embraced or respected at their beginnings.

You don’t have to sacrifice this genre or medium for that one, or lowbrow for highbrow, or vice versa. We’re complex, I tell ya! I can read Nietzsche and James Baldwin and bell hooks, then play Street Fighter and Dark Souls, then read a children’s book to my nephew, then watch an Adam Curtis documentary, then watch a football game, then go to a concert all in one weekend and analyze each of them for what they are and how they speak to me.

“High culture/highbrow” and “low culture/lowbrow” as terms sound fundamentally snooty, condescending, and divisive—I feel that—but noting differences of complexity between works of art, literature, and entertainment while observing and wondering what draws different audiences to this or that isn’t rude or offensive. We all do it! You can enjoy art in a multitude of categories and classifications, and disagree about which art belongs where. They fit inside you, you don’t shrink to fit inside them.

And again, who cares? Works will be evaluated and compared to other material by each individual. That’s how we think. High and low don’t exist independently—the high is built upon the low, and, like stairs, they’re part of the same structure. Everyone can and should be allowed to walk the art staircase. It’s big! Art belongs to humanity.

All that to say, distinguishing, critiquing, and categorizing art and literature in all sorts of ways isn’t a problem, nor is it even a solid thing; it can be helpful and educational, and it’s essential for developing the complexity of ideas and mediums—but withholding access to categories, or judging who should respond to what and how, or being cruel or dismissive to people for their taste, most certainly is.

I won’t quote too much here, but if you look up Virginia Woolf’s writings on the highbrow/lowbrow topic, you’ll find oh so many sharp, witty, and interesting thoughts! Excerpts from "Middlebrow: A Letter Written but Not Sent" by Woolf:

“Lowbrows need highbrows and honour them just as much as highbrows need lowbrows and honour them. This too is not a matter that requires much demonstration.”

“…the air buzzes with it by night, the Press booms with it by day, the very donkeys in the fields do nothing but bray it, the very curs in the streets do nothing but bark it — 'Highbrows hate lowbrows! Lowbrows hate highbrows!' — when highbrows need lowbrows, when lowbrows need highbrows, when they cannot exist apart, when one is the complement and other side of the other!

“How has such a lie come into existence? Who has set this malicious gossip afloat?”

What is your attitude towards the collectible art market? You just had a record sale for modern original art with the pages from Fall Sunrise #1 completely selling out at your art rep Felix Lu’s website, but for the most part, you stopped making your originals available for purchase. In the past, you have said that this was because part of your process involves regarding your art as a journalistic measure of your progress. I imagine this is a difficult and conflicting situation to be in.

It’s weird! I’ve lived off of original art sales for many years of my life—freelance art doesn’t often pay consistently or comfortably from any angle (unless it does—but when will it fall apart?)—so I suppose I shouldn’t be too conflicted, but alas! I am.

Someday in the future when our modern empires have fallen, and power has shifted hands, and English is as dead as Latin, I pray the only record of me will be on BabyNames.com where someone will look up “Tradd” and the description shall read in a beautiful new tongue:

Gender: Whatever.

Origin: Who Cares?

Meaning: “I Struggle.”

On one hand, I’m deeply grateful for the collectible art market, art collectors, and anyone who purchases art. They invest in artists and the art form—amazing! Thank you! Truly! Collectors help fund artists’ careers and future projects. I would not have been able to spend two plus years drawing Fall Sunrise had I not sold my art from Silver Surfer: Black. The Renaissance doesn’t happen without the Medicis and other wealthy families dumping money into the humanities, you know? The often essential relationship between artists and patrons is a known quantity—’tis an old one! Art takes time, and time is money, blah blah blah, you get the math. The art outlives us!

On the other hand, I don’t want to sell my art. I want to keep it all! My art is my journal, and I want to keep my memories. How else will I activate them in the years to come? What is money to memories?

Then another—I have three hands—I want to give it all away! I want to say, “Fuck it!” and share it with whoever passes me by. I love giving artwork to friends, contemporaries, collaborators, and loved ones—I’ll never stop doing that.

Then one more—my fourth hand, a skeleton—oh, what does it matter? I’ll do every option based on what I need at that point in my life and career. We keep, we share, we buy, we sell, and nothing comes with us. Feeling good ain’t one of life’s promises. Do what you’ve got to do and help your contemporaries do it too!

Beyond having technical drawing ability, how important is it for an illustrator to have an artistic philosophy? Can you describe how your own personal practice has changed over time, and how your career trajectory might have been altered by this evolving commitment to your artmaking?

You know, I don’t think I’ve ever thought much about having an explicit artistic philosophy until right now. That’s a good question. As I’m sitting here turning it over, I certainly have philosophies, I just don’t usually put words to them because they adapt. I don’t think I can pin it all down presently, but I’ll share a story:

I remember when I was very young—back in pre-school, maybe 4 years old—we were drawing pictures of our families in class. It came time for recess, everyone’s favorite, but I asked if I could stay inside and continue drawing. The teacher was kind enough to ask another teacher or assistant to stay with me while I worked. I finished up the drawing and I was happy with it. When the class returned to the room, they were all standing up facing in my direction—everyone was looking at me—and the teacher announced, “Hey class, Tradd stayed in from recess to keep drawing. Let’s all look at the finished art!”

The teacher displayed my drawing, and the whole class burst into laughter except for three friends: Sean, Stephanie, and Kendal. Now, I was a super sensitive kid; I would typically lose my shit and lash out, or just leave a place and hide in a situation like this. I would do anything I could—run, fight, twist, turn, bite—to escape and be alone if I thought I had failed at something. Just inconsolable! Sobbing, self-loathing, incendiary perfectionism! But for whatever reason, in that moment, beyond a deep gratitude and life-long affection toward my three stalwart friends whom I love to this day, I felt absolutely nothing. The good nothing! I remember thinking, “None of you understand what this means to me, and you never will, and that’s okay. We don’t share the same dreams, and it doesn’t matter.” No malice in any direction, no embarrassment, no shame, no joy, no hurt, no “I’ll show you!” Just pure, blissful NOTHING.

That’s art for me. It’s not between me and anyone else—no competition, no judgement, no walls, no needs. No one can touch it, and no one can touch me, and no one can change anything, or tell me anything, or take anything from me. So much of my language is steeped in a religion I let go of a lifetime ago, but that language still carries power and beauty to me, so, for lack of a more powerful metaphor, art is between me and God. No one else is in the conversation. It’s between me and the universe, the spirit, the sky, the stars, whatever language you want to put on it—it’s my holy ground, and it takes up no space beyond my body; it’s amorphous, androgynous, and quiet, and mobile. Between the sun and my soul, and a silent faith in nothing but life itself, which requires no faith at all, only being. It’s not for anything or anyone, and no one owes anyone anything anyway, and no one will hurt me there—I won’t allow it.

How mindful are you of genre when you approach a new work? Are you motivated by the prospect of advancing new genre forms, or is there an “artistic nobility” in abiding by established conventions? Is a “pure” elaboration of a respected if timeworn tradition even possible or desirable?

I try to be very aware and mindful of genre convention. I think you have to be if you want to create something progressive or interesting. You can’t be subversive if you don’t understand the structures you’re subverting, right?

Succeed or fail, I enjoy trying to advance genre forms—that’s the work I’m drawn to as a reader—but that comes from a love of many established conventions. The attempt to dismantle, investigate, reassemble, and advance a genre comes from love—either the love of what that genre was, or is, or the potential of what you think it can become, and I don’t think those exist independently. Thinking of two of my favorite genres, fantasy and metal, gah, I just love great versions of that stuff however it comes. Traditional, avant-garde, whatever—gimme your best shot!

As for artistic nobility, for me that comes from honesty, inclusivity, and measured restraint. “Measured restraint” meaning “well-thought-out and intelligently presented,” not “holding back.” If you enter into a project and think, “I’m going to create exactly what I mean to, and I’m going to train and study hard to create it with skill and care, and I welcome every single person to experience it,” that feels noble to me. That feels respectable. It makes me think of a tree!

So whether an artist lovingly abides by genre conventions, viciously attacks them, or eschews them completely, whichever option can be a noble and honest expression. Nobility can look like tenderness, and it can look like wild fury. No matter which way you go though, I think it’s necessary for a creator to understand genre convention and history if they want to present something fresh and substantial.

And yes, I think pure elaborations of respected artistic traditions are absolutely possible, and highly desirable at that. I think it’s what we’re all aiming for in art—a pure expression in the language of a medium we love. Art traditions become tired and timeworn when artists stop being inventive, inquisitive, and challenging. Painting has been around for a long time, you know? That doesn’t mean a painter’s expression is any more or less pure now than it was in 1490, or 1940, or 3000 BC. For me, “pure” in the artistic sense means “present, honest, and individual.”

You’ve developed a reputation as an artist who will hunker down for long periods of time to devote yourself to books you are developing, only coming up for air, so to speak, at the time of the project’s release. Is this form of self-discipline a means to remove the distractions of the world?

It is indeed! I’m a slow mover, and one-track-minded. When I’m focused on a thing, I am goddamn focused. I just… whew. I need time! Sometimes, God help me, I just don’t want to speak at all or listen to anything anyone has to say. I don’t want to be polluted by over-input! I want to walk down my own little path in the forest.

The world is a distracting place—100 billion noises vie for your attention every second of the day, and that never changes. It’s very easy to become overstimulated, anxious, and tossed in whatever direction the wind blows if you’re not being intentional with your time and attention. Focus takes training, and I like to train!

I think one of our greatest strengths is saying “No” at the right time. I agonize over that. So much of life is unavoidable and inescapable—I’d say most of it (I’d say all of it, but that’s a dead end). You can’t say no to cancer or tornadoes, you can’t change where you’re born or who raised you, and, personally, I haven’t yet shaken that I desperately want to please people; I don’t know if I can. So when I take the rare and beautiful opportunity to say, “No, thank you”—to distractions, to social pressures and expectations, to opportunities, sometimes even to loved ones—and grab the reins of my own body and time, god-DAMN. It feels powerful! I feel alive! You don’t control me, world! I mean, it does, but I don’t mind sleeping with an illusion sometimes if it helps me wake up in the morning.

Monks are cool; the way they function is so special and aspirational to me. I’m not on their level of devotion to anything, but I’m pretty dang devoted to art. I think to dedicate your life to the service of others is surely the most honorable thing. I don’t think you have to be a monk to function with that ideal as your central goal, though. I try to emulate philosophies of service and practices of self-discipline and self-denial in my approach to life and work.

The more I can focus my attention on one single thing—usually art (or cleaning or walking)—it’s like time slows down. The world gets quieter, and the more at peace I feel. So if I can make intentional decisions to remove distractions by focusing my attention on something, I certainly try to. Making art is one of the very few practices where I can lose myself and hear no inner dialogue.

To what extent do you think that the fear of AI-generated art making artists obsolete is warranted? Do you believe that certain industries—say comics—will be insulated by these reverberations because readers do not want to see creatives ceding control of their craft, or do you think that it will lead to further splintering of the art form—between say, books with high art sensibilities on one end, and lowest common denominator offerings built entirely on market research data on the other?

I think it’s an understandable fear. I don’t share it at all—I don’t think artists will ever become obsolete, only different. Creativity is in our nature, and it will be manifested. Looking backward and forward, I see nothing that makes me fear losing art or artists—10,000 years of horror, and art remains a human constant! Beyond extinction, why would that stop? Every individual and generation fears obsolescence and death—we are and have always been obsessed with our own apocalypse—and technological advancements have a unique gift for stoking that flame (sometimes for good reason).

Counterpoint: I’m in over my head on this specific topic. How much can an aspiring ascetic have to say on AI art or market research data? Maybe I’ll be jobless tomorrow and dead the next—who knows? Call me a fool when I’m in the ground, I promise I won’t care.

For me, the implications of AI-generated material are more disconcerting in advertising, politics, news, social media, and things like that than they are in replacing creatives, but yeah, creative industries are often used in service of the aforementioned industries, so, “Yikes!” The whole thing is uncertain, I’ll grant you that. It’s understandable to swoon with dystopian angst and fall down a hole of “what ifs”, though I’d advise against it. What good does that do? I don’t know—I was happy when I was a janitor.

But I believe in people, truly! I believe in people because I believe in myself, or vice-versa—I don’t think you can have one without the other. The alternative is doom, and why should one dwell on that? Doom comes when it does, but I won’t invite it. Begone from me, despair! I don’t want you here! Problems arrive, and we face them; personally and culturally and what’s the difference? It never goes away.

I hope this doesn’t sound apathetic—it’s not—but when it comes to the splintering of art forms… who cares? Is every art form not already splintered a thousand times over across history? Is that not how new art forms come to be? The splintering of ideas, philosophies, communities, and art is as natural and old as humanity itself—it doesn’t necessarily spell ruin. It can, and it might, and it has before, but it also means newness and growth. That happens too! To assume the inevitability of only one outcome or another is a waste of one’s hard-earned anxiety. Who can say?

The way I see it—I’m going to keep my feet on the ground, I’m going to create art that I love, and I’m going to continue studying, supporting, and pouring into individuals and communities who do the same. It’s not naiveté, it’s a peaceful act of aggressive will. People are capable; you are capable, people. Believe it! I say I will occupy this art space, I will keep drawing, and I will keep supporting my fellow artists emotionally and financially until demise pries this broken heart from my bleeding chest! What else is there?

Fuck with me, death—we’ll kiss when we do.

—

P.S. - I didn’t take the opportunity within this interview to heap praise, superlatives, and thanks upon colorist HEATHER MOORE, and it makes me SICK! Heather is one of the most talented, thoughtful, and intentional artists and colorists I know—I can’t overstate how much she brings to the table as a creative collaborator. Fall Sunrise and The New World do not exist as they do without her. Thank you, Heather! Interview her next, will ya?

The post “Go Bleed On That Page, Hero!”: The Tradd Moore Interview appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment