‘Boredom is one of the most essential ingredients to creativity’: An Interview with Alex Krokus

It’s impossible to surf the web without stumbling upon one of Alex Krokus’s comics. Based in Brooklyn, Alex has been posting his autobiographical webcomic series, Loud & Smart, on Instagram since 2016, leading to cartooning gigs with oughts-era media darlings Vice and Buzzfeed. Alex’s work is immediate and precise in both visuals and writing: He is the master of the 4-panel gag, which often reflect the absurdities resulting from the intersection of the internet and modern life. Not only is he a masterful gag creator, he’s also a master of media: he’s translated his work into interactive shows, animated shorts, and onto the printed page. After publishing collections of his Loud & Smart comics with Pyrite Press and Silver Sprocket, he has published his first long-form narrative graphic novel with Chronicle, Talking To My Father’s Ghost, a memoir exploring grief and family after a parent’s undue passing.

In July 2025, I sat down with Alex Krokus to talk about his influences and creative process, the New York City comics community, and how he adapted his 4-panel cartooning practice into a 200-page graphic novel.

-Christina Lee

CHRISTINA LEE: Tell me about how you first got into comics.

ALEX KROKUS: First of all, thanks for having me on the show, Christina. Lovely venue.

Similar to a lot of cartoonists, I got into writing and drawing comics when I was really young. Newspaper comics, like Garfield, Foxtrot, and The Far Side were a big inspiration for me. So I mostly just drew gag strips when I was 6 up until when I was 10 years old. I drew them all in a big, fat sketchbook that my mom gave me, and my dad was pretty much exclusively my entire readership. I would draw a new strip and then I would show it to him. Receiving that positive encouragement when I was young made me feel like I was onto something.

When I was a preteen, I started doing more ambitious, long-form stuff. Kind of like superhero floppies. And I didn't really go back into doing comic strips again until I was in my 20s.

How did you end up in New York City?

I decided to go to FIT for college, and a big selling point of it for me was that it was in New York City. I viewed New York City as this big, creative social hub where you'll meet other artists your age or older.

I also liked that FIT was a state school and it wouldn't financially devastate me if I went there. And I think because I didn’t graduate with crippling debt, I was able to take bigger risks with the kind of art I wanted to make after graduating. When I went to FIT, I didn't even really make comics that much. I originally applied for Fine Arts, exchanged sketchbooks with some other students (as you do during orientation week), and those friends would look at my work and be like, “I don't know what you're doing in Fine Arts. This is so illustrative and representational; you should be in Illustration.” So then I switched to Illustration, which was definitely the right thing to do. The program was mostly editorial and book design; things I didn’t really have the sensibility to do well. So I discovered my passion for cartooning after graduating when I had a little bit more freedom to figure out what I enjoyed.

How did college impact your creative career?

I think the biggest thing that college did for me was give me the opportunity and privilege to think about art full time. I think that's the best thing that it has to offer to its students. That, and a community upon graduation. But I think that giving me a four year period where I just thought about how stuff looked and figured out my sensibilities with humor and storytelling just helped me answer the questions, “What do I have to say?” and, “What kind of art do I want to make?”

Time is such an important resource for having a creative career; even if it's passive time where you're just thinking and committing your thoughts to your craft. I never really had that in high school or when I was younger, even though I drew casually a lot. I think the fact that I committed to getting an art degree meant I was going to take being creative seriously and I needed to think about it all the time. And that time was really important.

You said you really started cartooning after you finished college. How did the New York City comics community look like right after you graduated, and how would you describe it today?

The thing I like about the New York City comics community is that it's vast, it's varied, and there's lots of subcategories in the scene that I don't think run as deep as in other cities. You have fancy superhero writers doing signings in Manhattan. You have the indie comic weirdos doing multimedia shows in buildings that aren't up to code in Brooklyn. You have the hermetic webcomic artists that stay at home in deep Queens, but will come out for a convention or something… You might catch some New Yorker cartoonists at a drink and draw too. And I'm grateful to know people in all of these scenes. Whether it's music or art or anything, having a lot of subscenes within a scene is a sign of health and diversity.

When I graduated, my first exposure to the scene was doing MoCCA Fest in 2012, a week after I graduated from FIT. All of a sudden, I was inundated with all these different artists, my age or older, who had very cartoon-forward sensibilities, which wasn't really in a lot of the things I was taught in art school. At that time, I was making a lot of scrappy, punk art– I was in a band that I made a lot of merch for. So the stuff that I was selling at MoCCA was a lot of illustrative patches and those zines you make out of one sheet of Xerox paper. During that fest, I met and traded work with artists like Michael Sweater and Jensine Eckwall, two big inspirations who are dear colleagues now.. It’s always nice going to MoCCA Fest because I always see younger artists having similar epiphanies like that. It’s a reminder that there's always new generations joining the scene, and I think that's great. It’s important for students to go out to fests because that's an experience you won’t really find at school or online.

What are you inspired by?

A big inspiration for my comic writing is animation. I love the era of sitcom animation in the 90s to early 2000s; The Critic, Futurama, Clerks: The Animated Series.

I think that the early Simpsons is peak for comedy. Very rarely have animation writers been compensated well enough to be able to comb through scripts over and over and over again to make them so densely packed with jokes. The drawings that are off model in those, like the early hand-drawn episodes, are so visually funny. And I try to take a similar sensibility with my comics where visual gags are sometimes the best kind of punch line. Every panel is an opportunity to have a smaller joke in there. And sometimes the punch line isn't in the last panel, and maybe the part that you laugh hardest at might be halfway through a strip.

Animation and comics are both a sequential art, and I approach the timing and pacing very similarly.

What does “on model” mean?

What does “on model” mean?

In animation, there's model sheets for every character in the show. There's certain rules, like how far apart a character's eyes should be; the proportions of their arms to their legs; things like that. The stricter a show is about being on model, the more consistent the characters will look. But sometimes characters go off model, sometimes intentionally. In Adventure Time, Finn's eyes turn into white circles with pupils to deliver a specific emotion. Or sometimes a character can be poorly drawn to emphasize a funny line read. Those are two examples of being off model.

Sometimes it's intentional for humor, and other times the animator flubbed a little bit. I love it when the characters go off model because I think that it's a reminder that all of these frames are drawn by hand, and there's a wonky charm to that. And it makes it feel more alive to me; makes it feel a little bit less like it was cranked out by a machine.

How did you get into comics after you finished college?

Shortly after I graduated, I was posting on Tumblr a lot, which was the style at the time… That’s when I first started doing comics with my raccoon avatar. There wasn't a consistent structure or format to it or anything. I would experiment a lot. Sometimes, I would do a long form skit, or I would do one that's shaped vertically so it can easily scroll. But there wasn't any consistency to it. None of it performed well, but I was having fun, so I didn't care about performance. I'm glad that that didn't get me down because I think it was important to workshop what I was doing.

I think it was only, like, a few years later when I started posting on Instagram and I was doing an art challenge with my friend K Downs for 30 days— we would give each other a prompt, and then the other would draw something based on that. One of the prompts turned into a four panel comic, and through that, I learned that the square panel looked good on every platform, and it was an easier way for me to cross post.

After doing that a few times, I really grew to like the pacing of a four-panel gag. Some comic scholars would say that most jokes work best with a three-panel structure, but I kind of grew to like the challenge of like, “What do you do with this extra panel?” You know, you can use it for so many different things… But I think that I embrace the four panel structure because it looked so good on the most platforms, so it was a form-follows-function sort of thing.

How did you develop your audience?

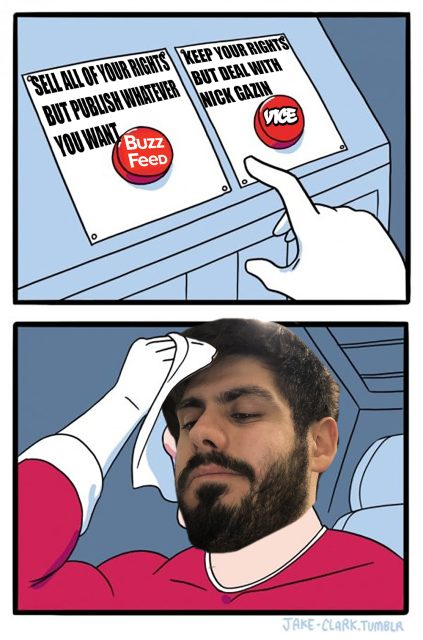

I'd say slowly and steadily. I would get a bump of viewership when I would do a commissioned comic for BuzzFeed or for Vice.

I got more of a bump in my audience when I started doing short-form video clips of my comic readings. I think that, years ago, to this day, Reels and YouTube Shorts get a lot of priority on their respective apps. And doing live readings of my comics were outfitted perfectly for that.

These videos grew my audience because people were charmed by how I could incorporate my animation sensibilities into the comic: like voice acting, and controlling the pacing of the comic; I think it adds a lot to hear an audience laughing in a recording. Some people love to be told when to laugh. They love a laugh track. And I think in our modern era, people just love seeing groups of people hanging out together and laughing.

That’s another unique thing about New York City’s comics community: we do so many readings. In video, it looks like a fun time, and it is.

Tell me about Vice Comics: how did you start publishing your comics through them?

I used to have a studio mate named Tyler Boss; he’s a great comic artist and friend. He was doing comics for Vice at the time, from the mid- to late 2010s. And he thought that my stuff would look great on their page, so he put me in touch with Nick Gazin, who was the Comics Editor at the time.

I got some exposure through working with Vice from 2018 to 19. I think the biggest thing that I got from there was going through the comics boot camp that is making work for Nick Gazin... He insisted that my Loud & Smart comics should be colored, which is something that I never did before. And I didn't really know how color would work with those strips specifically. So I kept sending him new colored versions of strips and he kept sending it back saying it's not good enough. It was maddening at the time.

I was going kind of crazy, trying to figure out new palettes to send him. But in retrospect, I appreciate how committed he was to finding something that worked for him instead of saying, “Yeah, sure, we could just run this.” I think it would have been easier for me if I weren't color deficient… Or if I decided to experiment with watercolors earlier. Watercolor is what I do now and I think it works really well, but at that time, I was doing everything digitally because I wanted to edit my comics easily.

At the same time, the never ending wealth of options that you have working digitally was overwhelming to me, and I was able figure things out a lot easier when I went back to working traditionally.

Did you start working traditionally when you were publishing work with Vice?

No, that was all digital, just because it seemed like that was what was popular at the time. And I thought I was still figuring out a style that would work. I think the jokes in the comics with Vice are good, and they still hold up. But I think that I didn't quite figure out what my look and style was yet.

That does sound luxurious to have a relationship with an editor who is actively giving you feedback.

That does sound luxurious to have a relationship with an editor who is actively giving you feedback.

Yeah, and although I was under the impression that Nick was annoyed and hated working with me… He kept hitting me up for comics, so I assumed this was just our working relationship. Any time I made a meme about how hard and difficult it was working with Nick, I would send it to him and he would respond with, “Haha, this is awesome.” I learned like, “Okay, Nick kind of likes working within this antagonistic dynamic,” and grew to understand what it's like working with him.

I consider you a master of media: you have a fundamental understanding of how to adapt your work into various different analog and digital platforms: you've translated comics into print, into Instagram, TikTok, live shows, etcetera… How do you think you developed this sensibility?

Similar to what I was saying before, I think about format a lot. And with that comes just thinking about what jokes work best in what media. Like, there are some gags that are best read as a comic strip. And then there are other ones that work best read aloud in a particularly funny voice. There are some comics that I think will work well on TikTok, but not necessarily Instagram. Specifically, there are some jokes that only young people on TikTok will like, and for the older folks on Instagram, it will confuse and anger them. That’s when I decide if a story I want to tell will exist as an animated short or as a series of four panel comics. And whenever I can, I like to mix the two. Like the gorilla saga in my last Loud & Smart collection.

Since I think so much about format and what media a certain story will be in, it makes me versatile with where and how I’m going to tell that story.

I think of this media versatility as a generational superpower: we grew up with analog mediums, like Sunday Funnies and graphic novels, and pioneered the digital distribution of comics through blogging and social media.

Millennials and Zoomers have this weird marriage of indie comic sensibilities and web comics because distribution is so online now. And form informs the kinds of stories we're going to tell. Now we’re doing these weird, multimedia comic things that’s another sensibility thrown in there. Now, people are thinking, “Oh, how am I going to read this aloud?” Or, “What music is playing while I’m reading my comic?” All of that affects how stories are told. And I’m sure in the next generation, there's going to be a new form of distribution that will make comics even weirder and more multidisciplinary than they are now.

I feel like your comics are very relatable, immediate, and efficiently crafted. What is the process behind creating the perfect four panel gag?

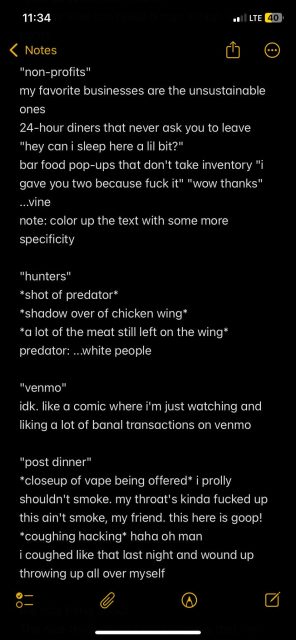

As one might guess, a lot of my writing is initially inspired by daily life, and sometimes a conversation with a friend will evolve into a joke. Sometimes, something I just observe on the subway can become that. And sometimes those inspirations will immediately translate to a four panel comic, and I'll go home and draw it that day.

Other times, it'll be a line of text that will live in my Notes app for a year before I revisit it and realize, “I know how to break this up into four panels now.” So sometimes it's a slow simmer, and other times it's immediate inspiration. And since I've been doing it for so long now, I have a folder on my phone of just hundreds of half-cooked prompts that aren't quite ready yet. I had to make a new file recently because my old one is just so long now that by the time I get to the bottom, the scroll is delayed and slow. But yeah, a lot of it's just observed, written down, and simmered.

What does the prompt usually look like? Is it like a sentence or two, or is it more like a paragraph, or does it vary?

It's usually five lines. First line is just the title of the comic. First panel is a line of text; either describing what's happening or what someone is saying. And then four more lines, one per panel. I have a couple of friends I’ll text asking, “Do you think this works?” James, the worm, is a trusted confidant I hit up often. We write together, we host live shows, we make short films; so we really understand each other’s sensibilities. I can send him a script that’s just those five lines with no formatting, and he’ll get it because he understands my shorthand. It's really nice to have colleagues like that. We went to the same college, so we grew up together in a lot of ways. I think we trust each other a lot with the work we make. We usually get each other’s eyes on something before we hit post.

Speaking of the worm, and I'm sure you get asked this all the time, what’s the thought process behind the animals that represent your characters? I noticed in your book, your dad is an owl, you and your mom are raccoons, and your brother is a bear…

It varies from person to person. Sometimes it's as simple as, “Oh, Aunt Carol’s favorite animal is a dolphin, so I’ll draw her as a dolphin… she’ll like that.” Other times it’s more vibe-based, like, “This person is totally a little rat. They’re just giving rat energy. I wonder if they'll like this? Only one way to find out!” So sometimes, it’s just a look.

With my family: I drew my dad as an owl because he was always a pillar of wisdom. I drew myself as a raccoon because right after college, I lived in a collective house where a housemate caught me bringing in a bag of dumpster bagels from behind a cafe - we do what we can to get by in post-grad life. She called me a squirrely little raccoon, and I kind of liked the sound of that. I probably drew myself as a raccoon later that day. Maybe unfairly to my mother, I drew her as a raccoon too because I look just like her, so that was some reverse engineering. I drew my brother as a bear because he's just a big, fun guy. It was more vibe-based when I got started handing out animal avatars to people. Friends and family who got animals early on in my career… those are sometimes decisions I wouldn’t make now, but I stick to them. I try not to retcon too much.

You’re a cartoonist who also works in animation… What’s it like pitching animation versus a graphic novel?

You’re a cartoonist who also works in animation… What’s it like pitching animation versus a graphic novel?

The biggest difference is that for a graphic novel, you're selling a story that starts and ends. For animation, especially television, you’re pitching a cast of characters that, ideally, never ends. From an executive’s perspective, they want season after season. The characters are the core of what you’re selling.

Also, graphic novels have a smaller scope. Fewer resources are needed, so you have more control and can be a little weirder or more nuanced. In animation, you have to convince a lot more people that your project is worth making. There’s more red tape and bureaucracy.

With graphic novels, it’s like making your own film. You're the writer, cinematographer, production team: all of it. So you have more control, but also more jobs.

Yeah, with animation, it’s not just a TV show: they're thinking about licensing, toys, merch...

Exactly. Even with an animated film, there needs to be open-endedness. There might be a sequel or a series later. Publishers would like to release a sequel, but that’s less baked into the pitch. If you just want to tell a story that starts and ends, a graphic novel is best.

What was the story behind Talking To My Father’s Ghost, and what was the pitch process like?

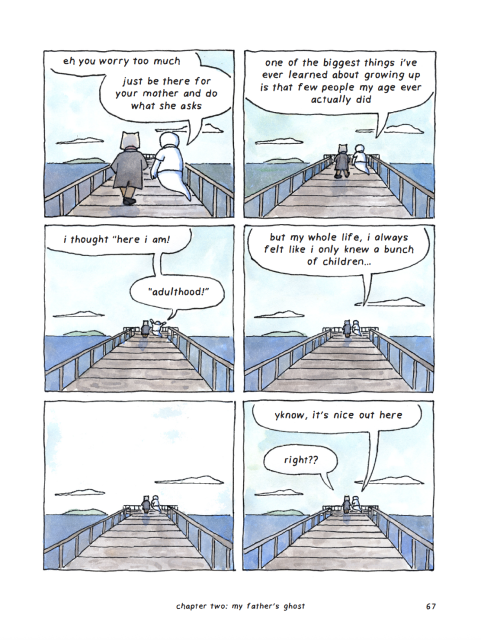

In late 2021, my father passed away. I was working on an unrelated pitch for another graphic novel when an editor reached out, asking if I’d be interested in making something original with them set in the Loud & Smart universe. I started reformatting that idea for a graphic novel.

But after my father’s death, I really wanted to process my grief. I talked to my agent about telling a story that explored the question: if your deceased parent came back as a ghost, what would you want to talk to them about? He said it sounded like a great idea. I also told him I thought the story would just fall out of me, like I wouldn’t be able to stop writing. And he said, “That’s the route, then. Let’s abandon the other pitch.”

Bless my agent, Ed. He really helped me carve my marble of grief into something worth sharing. We shopped it around. There were a few iterations of the pitch. Originally it was black and white, one panel per page, kind of cinematic. But Ed suggested doing it in color: it would be easier to sell. I groaned, because people love color so much, but I’m glad I was pushed into that challenge. That’s when I pivoted to watercolor and found a style that made sense for the book.

A few publishers were interested, but ironically, not the one who originally approached me. There was a bit of a bidding war, and Chronicle came out on top. I’m really grateful. My editor, Natalie, totally understood what I was going for and helped weigh in on certain decisions I struggled with. As an indie cartoonist, I don’t often have that kind of editorial support.

James is sort of like your editor.

James is sort of like your editor.

Yeah, I’ve always relied on friends and colleagues to tell me which script or version worked better. Having a professional editor whose job is to help you make the story coherent was a huge asset, especially since this was my first full-length narrative.

What was the process behind adapting your four-panel writing style into a long-form graphic novel?

I wanted to stick to my strengths, so I came up with a format where the vast majority of chapters are two-page spreads with 11 panels. There were a few reasons for that. One: it kept the scope similar to my four-panel stuff. Two: it helped capture the rhythmic passing of days– the book is about the first year of grief, awkwardly stumbling through the seven stages. Keeping the chapters consistent in rhythm and pacing captured that. And three: I wanted the book to feel like reading a collection of Calvin & Hobbes Sunday strips - something I loved to do in the tub as a kid - but with an actual narrative.

Natalie helped outline the arc, and then I broke it into smaller chunks. Some chapters move the story forward, others add color to relationships. It all adds up to a cohesive story.

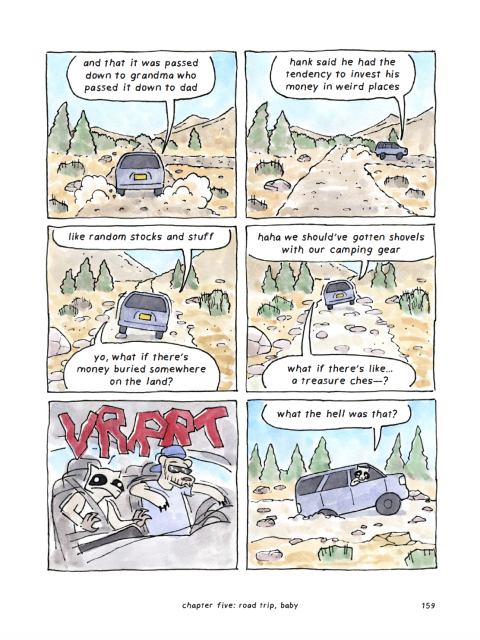

Yeah, I think for me, the chapter in Arizona where you and your brother get lost trying to find your father's land is one of my favorites. It feels like the emotional core of the book. How did you go about creating it?

When I pitched the book, I knew the arc, but not everything that would happen in each section. My brother and I had a real-life trip planned to road trip into the Arizona desert to check out this cheap plot of land that had been in my father’s side of the family for generations. I knew I wanted that to be a chapter, and that we’d probably talk about some real stuff out there.

So I blocked it out in the outline, even before it happened. And it did wind up being an important trip. It was full of material I wanted to put in the book. I had to trust that the experience would be worth writing about. I really appreciate that both Natalie and Ed trusted that open-ended format. It’s kind of how I write everything.

How did you approach the visuals? I really love how that chapter looks.

How did you approach the visuals? I really love how that chapter looks.

Thanks! Since the book spans an entire year, I wanted to use it as a challenge for depicting different parts of the year or time of day through color. I’ve driven through the Southwest before—it’s my favorite part of the country. Even though a lot of it is sand, it’s impressive how different sand can look depending on location or time of day.

I wanted to include segments that captured early morning, or night with a pink sky, or a bluish-purple dusk. I saw it as my Monet haystacks series, in a way—just using color to convey time, mood, place.

How long did it take for you to create Talking To My Father's Ghost?

From making the proposal to turning in the final version, it was probably close to three years. The book itself took a little over two years, and the proposal almost a year, because there were a few different iterations. I didn’t expect it to take that long: I thought it would be maybe a year and a half. But actually making the book was a very sobering process. It taught me that if you want to make something really good, it’s going to take years. Maybe not three years of full-time work, but a lot of that process is just thinking. A lot of it’s commuting to work and thinking about how to solve a chapter you’re struggling with. When you rush things, you lose that digestion period of when you’re problem solving in your head. It’s kind of like being in school full time.

I mean, do you ever do that thing where you just stare at the pages, trying to figure out what’s working or not working?

Honestly, not that often. I think a lot of my thinking happens away from the drawing board. Maybe because I work simply or scan a lot of things at first. But a lot of my problem solving happens when I’m biking, walking, or in the shower: times when I’m not looking at my phone. That’s when I naturally think about how to fix something.

Boredom is one of the most essential ingredients to creativity. Boredom kicks ass.

Boredom does kick ass.

Boredom does kick ass.

Yeah. That could be the headline— that’s not bad.

Although the start of my career, and even now, is very associated with being online, my best ideas come when I’m not online. Not looking at my phone, not being barraged with stimuli. That’s when I figure out what I actually have to say.

The same goes for visual problem solving; figuring out composition, for example. You just have to go offline and look at it without all the noise.

This book feels like an interesting evolution of your cartooning: it explores longer form and has a more serious tone, but your sense of humor is still you. Where do you see your cartooning going next? Will we be seeing more memoir and melancholy?

It was really nice working in a graphic novel format. It makes room for the melancholic. Humor-based gag comics don’t always allow for that. Every strip has to work on its own, and for many people, it’s the first time they’re seeing the work, so it has to land in four panels.

With a graphic novel, there's room to explore different emotions. That was exciting. I got to lean into the full range of my personality, which isn’t always being the funny guy. I got to be contemplative, offer some life advice. That felt really good.

I really enjoyed the scriptwriting process; being able to write beats that aren’t just punchlines. I'd love to do more of that, whether it’s another graphic novel or writing scripts for television. I scratched an itch I couldn’t reach with four-panel comics.

So we’re nearing the end of our conversation… I wanted to ask more general questions. How does a cartoonist build a sustainable career?

Great question! I have a few thoughts:

First, figure out what medium excites you and feels natural. A cool thing about cartooning is that it’s inherently multimedia. Even if you’re just doing traditional gag comics, you’re writing, drawing, composing shots… you wear a lot of hats. Ask yourself what part of the process you like most. That can influence whether you want to work in comics, animation, video games: cartoonists are shapeshifters.

Second, think about sustainability. I tell my students this all the time: there’s no shame in having a day job. That’s what keeps you drawing in the long run. People think they have to go full-time to be successful, but that can lead to burnout. A sustainable day job keeps you focused on your work and not stressed about rent.

That’s what I did for years: I was a cheesemonger, I worked at farmers’ markets. Those experiences informed my work. I made weirder stuff because my personal work didn’t have to pay the bills: I could experiment with rotoscoped music videos and strange comic reading shows.

So your two big pieces of advice for cartoonists: find the right format and find a side job?

Yeah. If you don’t need a side job, that’s awesome. Whether it’s because you blew up early or have supportive parents… either way, whatever keeps you drawing in the long-term is the right move.

And what do you hope for the future in comics?

In comics, I’d love to see more transparency in how the industry works. A lot of people think once they’re published, it’s Easy Street, but it’s not. You constantly have to adapt. A distributor might go bankrupt, a publisher might write a sloppy contract that doesn’t specify compensation… That stuff can be a rude awakening.

The more people are transparent about the deals they’re getting, from publishers or through social media, the more artists can regulate expectations and plan sustainable careers. A big following doesn’t mean you're making money. A book deal or award doesn’t mean you’re “killing it.”

Do the research. Be transparent with your colleagues. There’s a cool database online for commercial artists called Litebox Info. They have a user-submitted Rate Finder that discloses how much artists were paid for certain jobs. I think community resources like that rule.

And for cartooning?

Cartoonists should stay curious about new forms of storytelling. If not, they risk becoming jaded or crotchety when the new guard starts working in new formats;maybe on new apps. Always experiment. Otherwise, you become the grouchy old guy in a black T-shirt mad that no one makes comics like you anymore.

I think we all—including myself—start to gray and look different from younger cartoonists. You should be interested in what they’re doing, even if it’s not your thing. They’ll eventually have more power, and they’ll shape what the scene becomes.

Any last words about the book, the comics community, NYC…?

Any last words about the book, the comics community, NYC…?

Yeah. Go out to live events. That’s my biggest advice.

When I first went to MoCCA Fest, it was hugely inspiring. I saw work I’d never seen in college or online. A lot of people think school or social media defines what’s important, but I’ve gone to fests where an artist’s table is mobbed, and they have just a thousand followers. The internet doesn’t determine who’s making great work.

Go to local indie fests. Go to the weird multimedia events happening after the convention. Talk to people. That breaks down resentment in the scene and makes the community stronger.

Someone might be a silent hater online, then go to a con, meet the person they were subtweeting, and realize they’re actually really nice. It breaks down walls. Or, sure, sometimes you meet a person you admire and they’re weird to you, and now you hate them… But overall, in-person events make the scene healthier and less toxic.

There’s not a lot of money in this world, so social currency is often what’s being traded. That’s why being kind and showing up matters.

Any other thoughts?

Buy my book. It comes out in a month.

[That in-a-month is today, the dateline of this interview -Ed.]

The post ‘Boredom is one of the most essential ingredients to creativity’: An Interview with Alex Krokus appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment