Comics abound in maladjusted weirdos - but then, so do books, movies, music, the government...

Maybe better to say maladjusted weirdos are a constant throughout our lives, though comics is a haven for the type. Hell, perhaps you might stare into the mirror, some lonely nights, wondering if you’re the weirdo. We’re all friends here. No judgment.

Let’s meet Egbert, the star of I Never Found You, by Emma Jon-Michael Frank. New from Floating World, about as strong an imprimatur as comics can offer in 2023. An excellent, thoughtful, haunting piece of work. Egbert is, in all frankness, a thoroughly unpleasant person. He makes everyone around him uncomfortable. You can’t even say he means well, because over the course of this book we see into the inner workings of the man’s mind. He doesn’t mean well because he doesn’t really mean anything. He’s a full-grown man walking around with the emotional range of a toddler, trying to get attention from people who have no interest in him. It doesn’t read as endearing because the unleavened fact remains that he’s as deeply unsettled as a human being can be while remaining vaguely functional. Bad vibes all the way down.

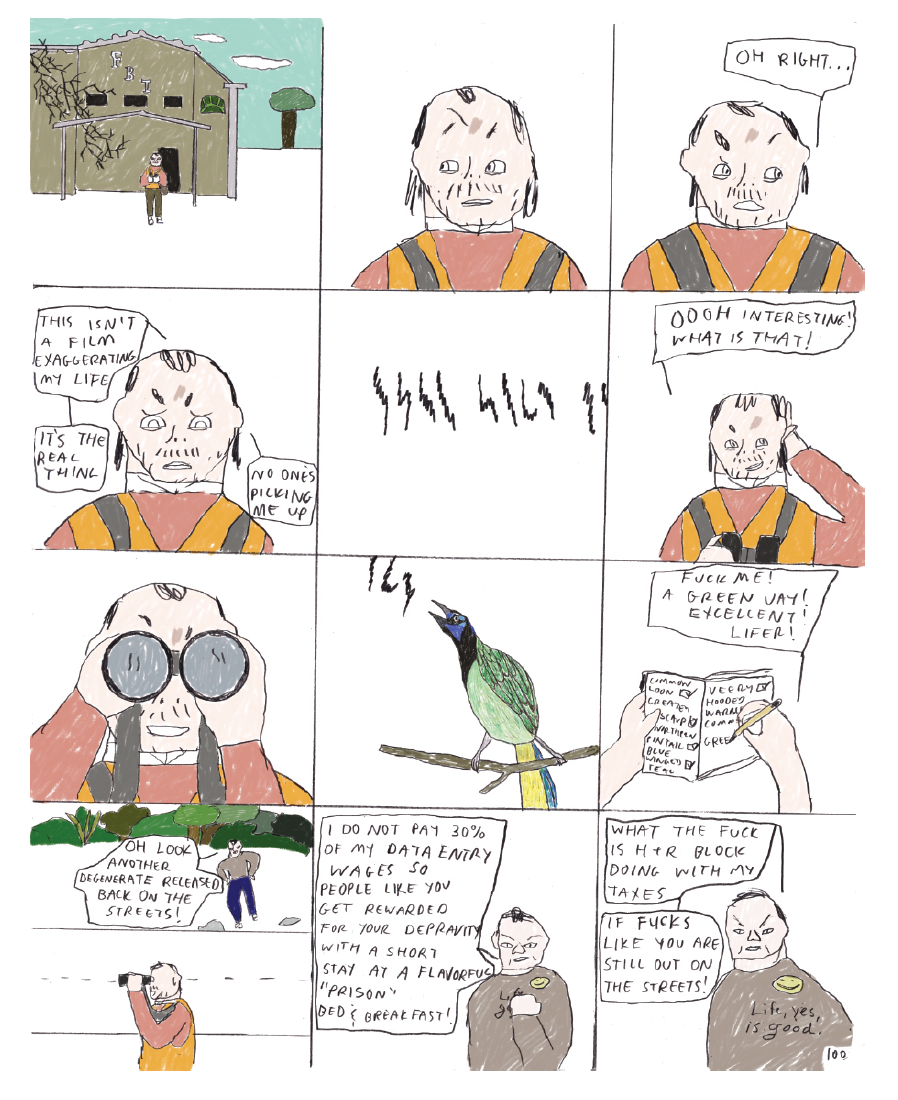

Much of the the book is concerned with the noble pastime of birdwatching, or “birding,” as the hip kids might have it. Hoisting binoculars in nature; real Jonathan Franzen hours. (Apologies to any birders in the audience, but it’s objectively funny that the most peevish man in literature is the hobby’s most prominent celebrity aficionado. Anyway.) Egbert is obsessed with looking at birds, even if he’s actively terrible at it. Much of the book is concerned with trips organized by Egbert’s birding club. Everyone else always sees the most amazing specimens, but poor Egbert is always just looking in the wrong direction, or has his nose in the guidebook, or his head up his ass. There’s always something in the way preventing him from doing the most simple thing - that is, looking directly in front of him.

One’s thoughts naturally turn in the direction of Frank Santoro’s Pompeii, C.F. and his Powr Mastrs, the fruit of the tree that was Paper Rodeo. Funny, in hindsight, to reminisce on the debates about craft that used to rage in these very pages; so many of the most vital comics of the past two decades have been predicated on peeling back the skin of competency. The problem is that the generation of cartoonist who came up in the 1990s and found lasting success in the early 2000s rather gave consummate craft a bad name. The eradication of human imperfection in the task of illustration was the goal, whether stated or not, and an alienating creed for many. But then, pull out one of those big Paper Rodeo broadsheets - a truly unwieldy package. I’d like to see you get a CGC grade for one of those fuckers. Cheap newsprint filled with wild shit. People drawing like children. Leaving eraser marks on the page.

Frank’s work is raw and expressive. Purposefully primitive, intentionally ugly. Makes sense for a story like Egbert’s. The narrative remains tightly on Egbert’s life and adventures; we hear his thoughts throughout. The pictures form something like free indirect discourse, to use a hoary old technical term - not precisely Egbert’s view of the world, considering just how ugly and sordid his own actions, how unvarnished his rationalizations. But close enough. We see all the painful little ironies very clearly, even as Egbert manifestly does not. He’s interacts with the world on the level of a petulant child, and so his world is drawn the way a child might draw it.

I spent some time looking over Frank’s Instagram account. Most of Frank’s output on that platform comes in the form of single-panel drawings illustrating personal observations. Not quite daily affirmations, but statements reflecting deep thought about one’s own emotional management. Not really art to be critiqued as such, I don’t think, but interesting nonetheless. A sample, from July 27, reads: “Why do I feel like I’ll lose everything and everyone if I’m honest with myself and others?” The accompanying illustration: a self-portrait of the artist with enormous extremities and a tiny head. From June 7: “It’s so freeing when u realize that another person isn’t the solution to your happiness...” Very relatable sentiments. The path to empathy leads through a greater understanding of self, sure. I’ll drink to that. Half diary and half process work. Quick sketches, very energetic. In its yearning for healthy sentiment, the dark mirrored inverse of I Never Found You.

Egbert, of course, can’t even look inside himself when he’s ensconced in a sensory deprivation chamber. He becomes fixated on a painted bunting (that’s a kind of bird, and if you get confused about birds, there’s an index in the back of the book). The character represents a kind of hell, a half-life misspent without reflection. For someone who spends all his time trudging across meadows looking for birds, he remains remarkably ignorant of context. The discussion swirls around climate collapse, the winnowing of bird populations due entirely to manmade threats. The birding club is a refuge from the outside world, but also suffused with foreboding reminders of suffocating doom. During one meeting they bring out a tape recording of birdsong and exult in the fantasy of an intact ecosystem: “Why don’t we recreate the outside world we love inside the safety of this room?”

There’s been a great deal of talk about the epidemic of loneliness, a real problem created to a large degree by the demands of a cruel world that has gradually winnowed down the empty space in peoples’ lives. You know, the same empty spaces in which we used to fit things like bowling leagues and bridge clubs. People still like bowling - or, at least, I still like bowling. I’m awful at it, but I enjoy it. Who has the time these days? In making the time for his birding group, Egbert is already doing better than most, one supposes.

All Egbert really cares about, however, is having found a severed hand in a tree. Not a bird but a crime scene. Now, admittedly, if you or I found a severed hand in a tree, it would probably be the most interesting part of our week too. The problem is that this one tiny drop of notoriety goes straight to Egbert’s head. Finding a body part in a tree makes people pay attention, at least for a few minutes. And then the group moves on to something else, because there’s only so many ways you can say, “I thought it was a bird but it was just a severed hand.”

Becoming an eyewitness does nothing for Egbert but make him a suspect. The FBI agents who interrogate him aren’t quite sure if he’s guilty or nuts, but soon seem to settle on nuts. The agents themselves seem a bit eccentric, seen as they are through Egbert’s eyes - identical twins possessed by mystical ramblings and given to strange pronouncements, such as, “We interviewed a stubborn narcoleptic one time.. Had to get into his dreams in order to hear him talk.... We shared breaths with him. We breathed in him. He breathed in us.” Just like how FBI agents talk, yes.

Egbert becomes so desperate to relive his glory days that he concocts a new story, planting a leg in the same meadow for him to find. But, of course, it’s not a real human leg. There’s a penalty to be paid to lying to the FBI about finding a fake human leg, naturally, so Egbert does some time sitting in a cell prior to being let loose with community service. Egbert sitting in his cell is one of the most effective sequences in the book, just a man hunched over on a prison bunk talking to himself, hemmed in by bars that look identical to the panel borders. “Was finding this hand going to change your life?” the question floats between the panels. “Are you going to let its purpose slip through your fingers, Egbert?”

The second half of the book plays out with Egbert seeking to confront the author of the severed hand, the actual serial killer the FBI caught when they weren’t dealing with Egbert’s attention-seeking behavior. There’s no small humor in Egbert confronting the killer and the killer himself being more than a little bit unsettled by the man visiting him claiming “I’m who you were contacting... I’m the one you were leaving clues for.” When, really, the killer was just leaving dismembered body parts of dead women in trees because he felt like it. There was no rhyme or reason to it. Egbert is convinced there is, and when confronted with a notarized memo from the universe to the effect that there is no rhyme or reason in the great tragedy to which he is a mere bystander, he simply refuses to believe it. “A woman is dead for Christ’s sake!” he roars into the visiting phone. “I don’t understand. For what. There’s gotta be something of value in this!!” It would be nice to think so, at least.

Egbert isn’t going to follow in the killer’s footsteps. He’s not a harmless man, but his harm seems to be primarily directed inward. After all, he says on the second page of the book: “I could not solve my inner mystery. And... I never found the thing I was looking for...” And it’s not like there’s any shortage of meaning in and around Egbert’s life. He just can’t see it, and so fundamentally misunderstands everything about being human. From having friends and looking through binoculars through to how to live in proximity to tragedy. Other peoples’ misfortune really shouldn’t be an opportunity for our own personal growth, but to be fair, Americans as a rule have a hard time remembering that.

The post I Never Found You appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment