I went to London recently and, recalling my love of the film Mr. Turner, decided to visit one the city’s museums with a dedicated JMW Turner exhibition. I am not much of a fine-art person; I know just enough to know my own ignorance. I can tell my Cubism from a pre-Raphaelite, but not much more (I can't tell you anything about them, But I can tell you they are different). Still, what I saw at the Tate moved me, shook me. Over a century later there was still power in these paintings, dozens and hundreds of them1. Nothing in a reproduction (especially on the tiny monitor you are probably reading this on) could do them justice. And while my eye turned, obviously, towards the large sea paintings- with their dramatic scenery and thousands of small details that felt more alive than any movie- the room I returned to several times was dedicated to Tuner’s later works. Some of them incomplete, backgrounds without foregrounds, ideas and notions half formed.

Works like The Departure of the Fleet (1850), depict the type of scenery Turner returned to many times before (crowds, boats, harbor, the sun bursting through); but any semblance of naturalism has been renounced — the scene is bathed in strange light, the background is hazy as if the city is melting, the people of the crowd are twisted into one another. Even before that, there's the mouth-filler that is Light and Colour (Goethe's Theory) — The Morning after the Deluge — Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843), a brilliant piece of work in which the colors appear to overwhelm one another, creating a true sense of a world awash with motion. A world that is no longer what it was.

Turner was, early-on, renowned for his use of color, his perception of light and its effects on environment. Even an ignoramus such as myself could see this with the naked eye. In later works, when he became more of a social recluse, we see something different. Or rather, Turner probably sees something different. These paintings are those of a man who looked directly into the heart of the sun and did not blink. The beauty in these works is not the same beauty to be found in Turner’s "prime period" (when he was at his critical and commercial height), it is a beauty all by itself. The mood overwhelms all other considerations, yet they are not wholly "mood pieces," because they are filtered through the talented hands of a man who dedicated decades beforehand to the self-improvement of technical matters. Few people could see as late-period Turner saw. Fewer still could turn what their eyes saw into physical object.

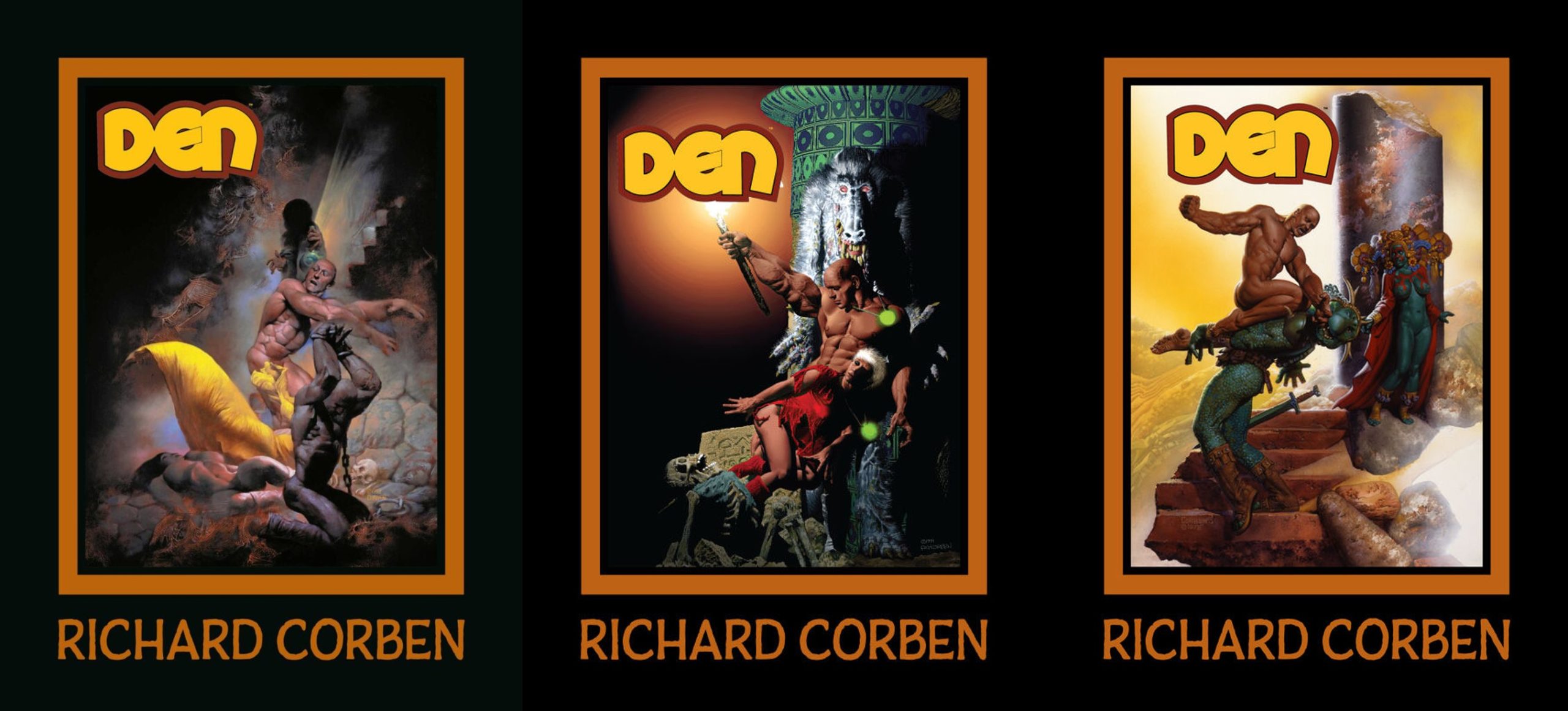

Why write all of this as a preamble to a review of Den? Richard Corben’s long-running fantasy saga is finally fully collected in five hardcover books by Dark Horse (as a part of the wider Richard Corben Library). It probably won’t be hung on the Tate’s walls in the near future. There is hardly a universe in which Richard Corben is counted amongst the artistic peers of JMW Turner. One drew the famed and respected people of the British Empire, scenes of history and national mythmaking — mighty ships that have actually existed and played part in the fulcrum of history. The other drew: monsters, big cocks, bigger boobs, some more monsters, asses, muscles to make Arnold Schwarzenegger blush, and even bigger cocks. It’s a whole different milieu. Pulp and lowbrow fantasy. A boy’s wildest dreams brought to life.

Fantasy — power fantasy, sexual fantasy — is as common as mud in the worlds of comics. There are many in comics who did that type of wish-fulfillment, many who drew big men who get to bed all the pretty women, many who drew monsters and battles, many writers with a penis in their typewriter instead of their hands. But no one could do it quite like Corben did in Den. Just like JMW Turner — looking at these works lets you know that you are looking through the eyes of a man who saw world in a different manner. A man who saw a more vivid reality than the rest of us; and who had the skill, the technical know-how, to translate that vision into reality.

"Vision" ... maybe a more apt comparison would be William Blake, or Austin Osman Spare? Not just artists but writers who had their own notion of reality. Tuner’s art was often preoccupied with physical reality (even when drawing fantastical scenes there is always a strong presence to them), Blake and Osman tried to touch the sublime. In between these pendulum swings lies Richard Corben.

Nowhere Fast

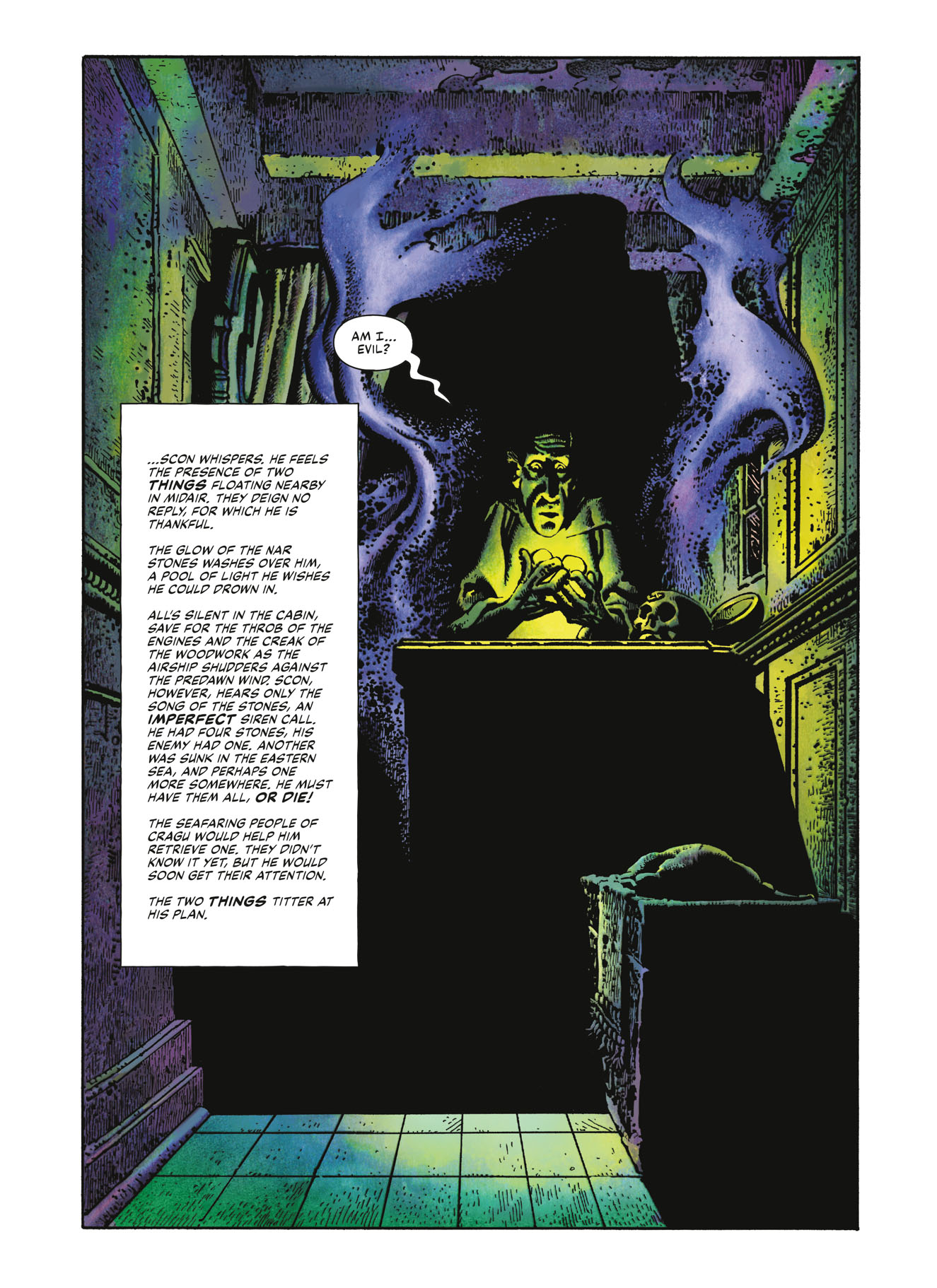

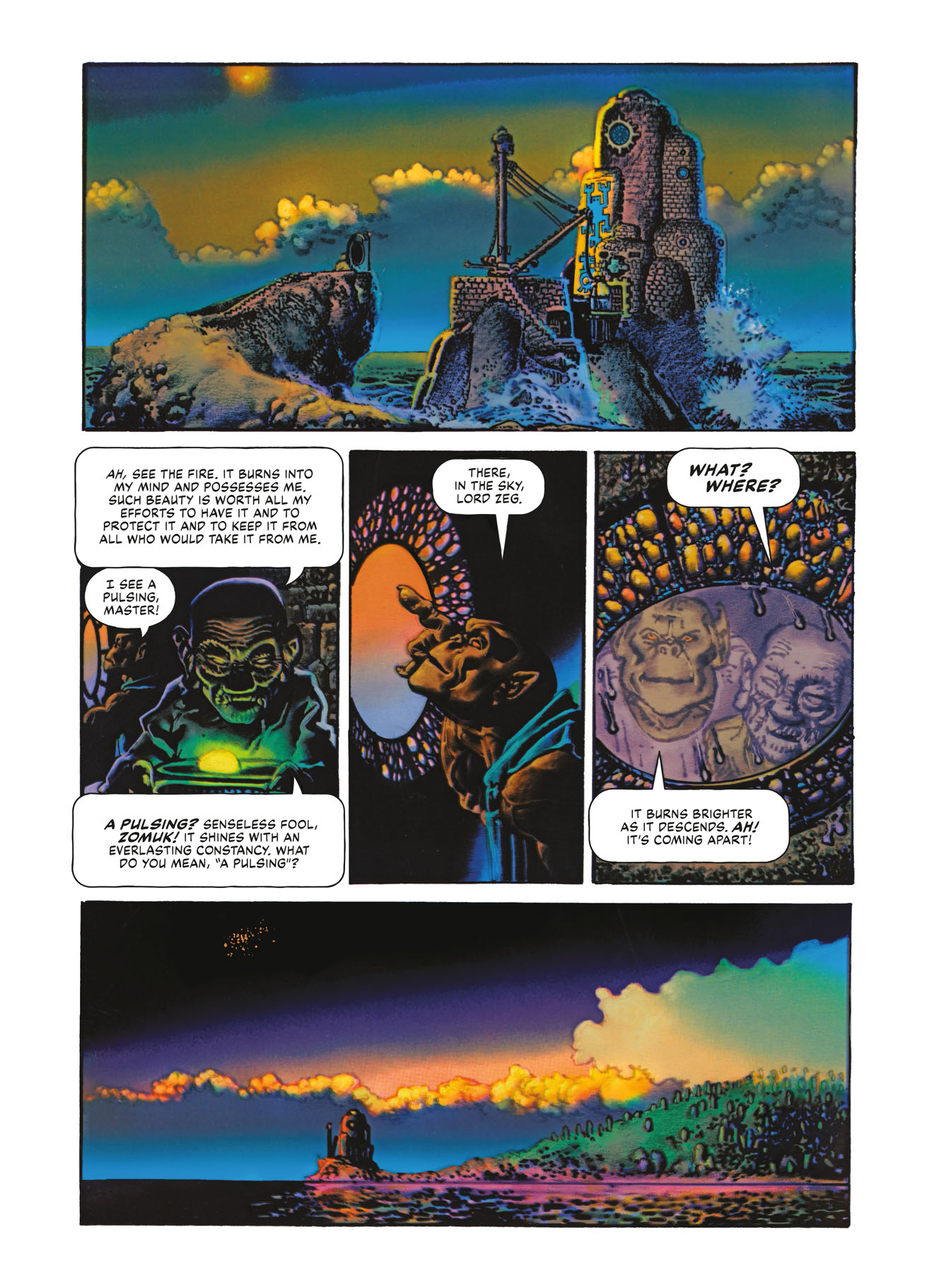

Corben’s Den stories take place in Neverwhere, a sort of anything-can-happen fantasy realm that combines elements of generic fantasy (kings, queens, magic) and science fiction (aliens, energy rifles). It is the same type of adventure-ready world that appears in comics ever since Alex Raymond took pen to paper and created Mongo in Flash Gordon. Yet unlike Raymond and his thousands of followers, Corben does not draw his world at a distance, he draws Neverwhere as if it truly exists. It is a ridiculous place, an impossible place. A world obviously not quite thought through2, but when you look at a Corben page suddenly these complaints are meaningless. I don’t know if Corben believed in Neverwhere the way Spare believed in his visions, but he draws it as if he does.

Corben’s own followers certainly believe in it. José Villarrubia, who does the art restoration and edits the whole Corben Library project, provides a forward or an afterword for each of the volumes. If you think I aim a bit high with Turner and Blake, Villarrubia goes further back, comparing Den to Ovid’s Metamorphosis. And you can kinda see it, if you squint hard enough (maybe The Satyricon, with its fragmented nature and general air of debauchery, would be a more apt comparison). Ovid’s most recurring theme was transformation — men to women, women to nature, mortal to immortal. In the first volume of Den a timid boy with geek physic is reborn in the realm of Neverwhere as a muscled barbarian, a transformation worthy of Charles Atlas (another comparison Villarrubia makes). Neverwhere itself also seems to be a sort of shifting land, if there is an internal logic to it I could not parse it. Fantasy world-building is almost always tenuous, but in Den it is utterly throwaway – the land is what it needs to be for the story. It is everything and nothing.

But the comparison between Ovid and Corben breaks at the language barrier. How can one even consider within the same hemisphere of the mind “My soul is wrought to sing of forms transformed / to bodies new and strange! Immortal Gods / inspire my heart, for ye have changed yourselves / and all things you have changed!” (Brookes More translation) to, “It seems I was floating in darkness for an extremely long time.” A lot of the dialogue in Den is perfunctory, the rest is silly. The register of conversation moves freely from everyday talk to Stan Lee-esq faux-Shakespearianism (“Fiend! You make love to me while your friends continue your mischief!”). The protagonist is named "Den," that’s hardly the name to inspire an epic, and is surrounded by many more monosyllabic fellows (Kang, Kron, Zeg). It’s a story that is hard to take seriously.

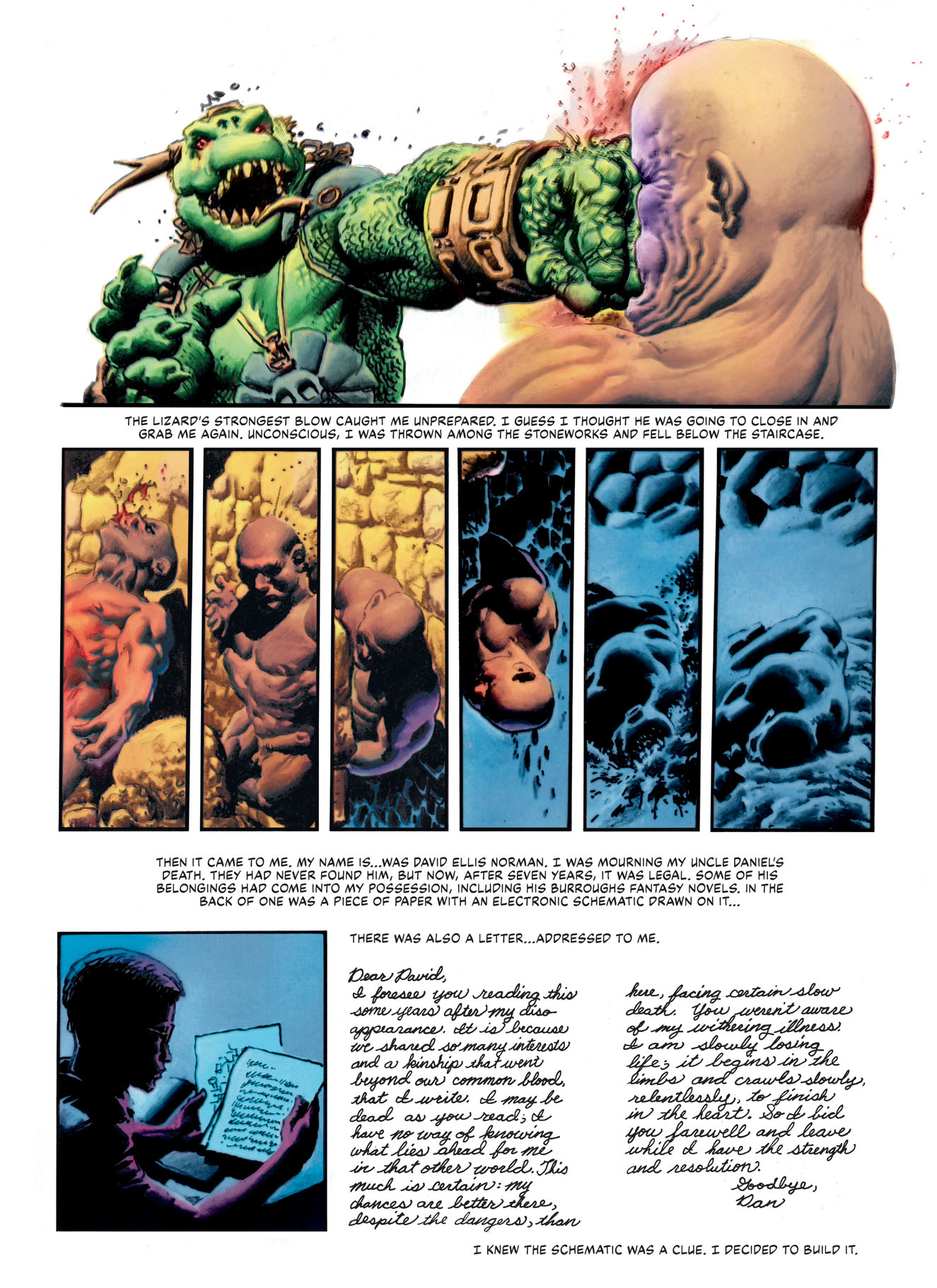

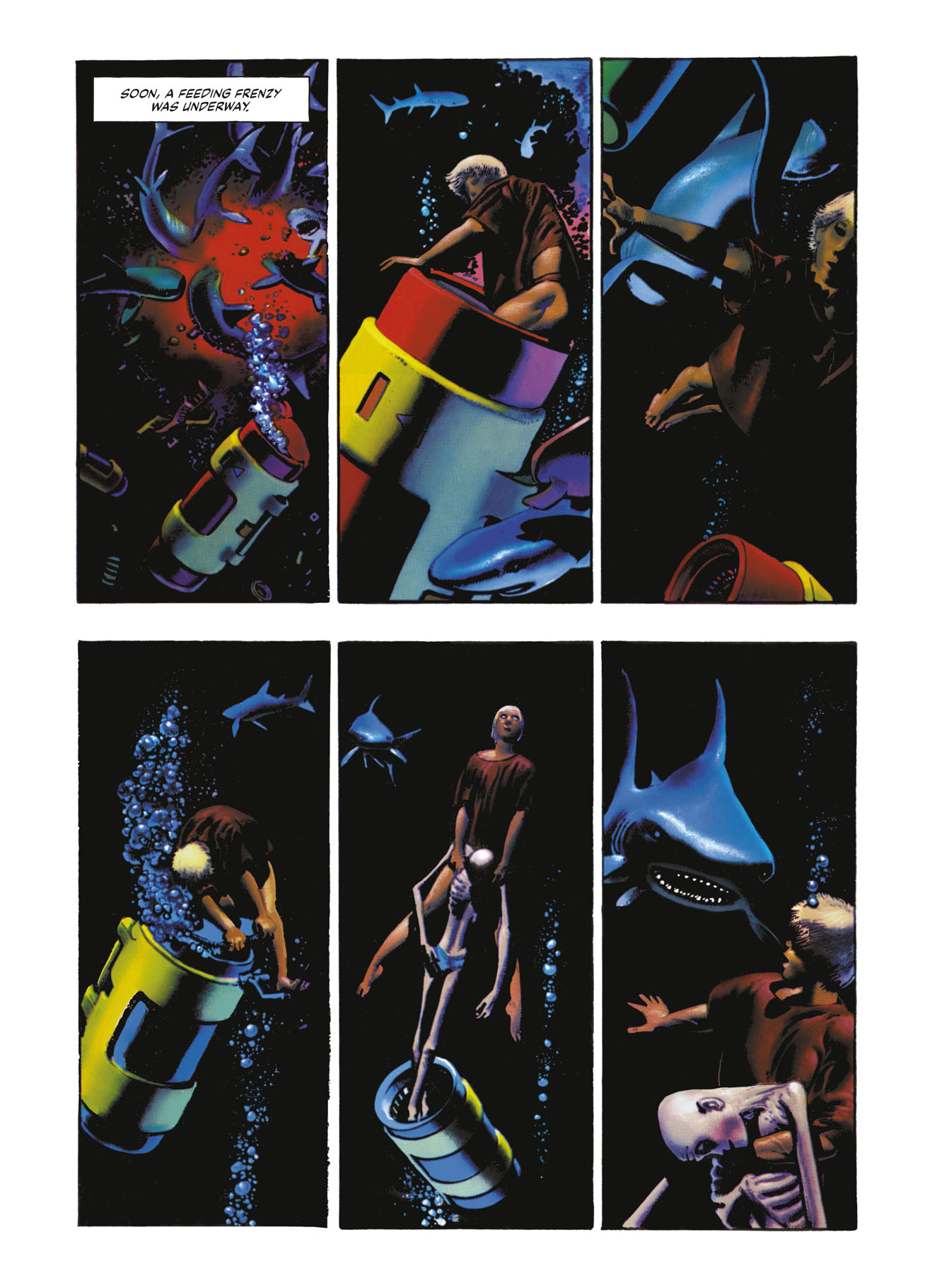

Harder still when considering the visuals. On the matter of Corben’s actual skill with pencil, pen and brush I would brook no argument. It is true that it takes a while to get used to his figures, which appear to be sculpted from clay, and that he sometimes appears overwhelmed by his own commitment to draw muscle and flesh contorting. Just look at the punch to the face in the page above, the skin ripples as if in slow motion; Corben's exaggerated sense of physical combat is like Kirby on steroids. It is also true that work is often uneven — you can see deadline pressure in all of these stories, as big moments of beauty give way to small moments of simpler storytelling.

For all his faults Corben can do things that few had done after and no one had done before. His color work, in particular, is like Greek Fire, understood but hard to replicate. Every book has an intro by another comics creator, and the thing they all harp on is his use of color and their attempts (if they are artists) to replicate it with little success. It's a cliché to talk about it, but this does not make it less true. This palate so deep one could never quite reach its depths is the reason the Turner comparison comes to mind. Few could think it, fewer could make it a reality. Still, what does Corben do with all that skill? He draws the lowest of the lowest common denominator.

There is no superego in Den, only pure Id. The muscles bulge, the penis swings, the monster howls. The stories are familiar, copies of copies of old pulp magazines. If someone like Tolkien considers every facet and every tree before he moves a single character, Corben appears not to think beyond the next chapter. Reading through several volumes at one go I still find myself struggling to understand how all the pieces go together, or recall which particular babe with massive tits am I looking at now. It’s confused and confusing. Some of the tales seem to have been made as solo adventures only to be reconfigured as tales of Den at the last moment. This is particularly true of the twist ending of volume three which throws a third character with the same name and look into the mix.

Is Corben taking all of this seriously? Does he expects his readers to take it seriously when he introduces an instrument called “The Nutcracker of Death”? The series certainly keeps a straight face. If it’s an act then Corben is better at pretending than Andy Kaufman. Villarrubia, who sets the tone with his introduction, certainly expects us to take it as seriously as we would all the classic texts he references. I recall when Fantagraphics began its Complete Peanuts series and some reviewer complained that Seth’s cover design basically dictated a particular sad-serious tone over Schulz’s much more varied expressionism. Even if one appreciates Seth’s art direction, it’s hard not to see the stern Charlie Brown on the first hardcover as an outsized declaration of seriousness. The presentation certainly radiates respect owed to the material. Something like Fantagraphics’ Atlas Library reprint series is also very respectful in design, but makes it clear the work is mostly, if not wholly, B-level schlock (they are being kind) whose existence is mostly valuable for historical purposes3.

The answer to the question above appears to be: "It varies." A friend, talking about movies, came to a conclusion that I think transfers to comics pretty well: Japanese works, on the whole, are much better about heaving a broader emotional rainbow in a single work than their American counterparts. A serious American comics tends to be serious all the time. A Japanese work has no problem moving from serious to silly, even on the same page, without the silliness offsetting the resonance of the drama. You could say Den has something similar going on. The Nutcracker of Death is funny — straightforwardly so — but the fate of the angel-servants in volume five (Prince of Memories) is horrifying and tragic. This isn’t an intellectual achievement but an emotional one. As the work becomes both large in scope and long in years, Corben shifts with time, growing older (but not necessarily wiser) and finding new stories to tell within the setting. In a way, the unbuilt nature of the setting becomes a strength, as it allows Corben to tell all manner of stories without limiting himself. Well …. as long as he can have giant male organs4.

Speaking of the Thing

It is hard for me, personally, to take Corben’s work seriously because of the in-your-face sweaty-teenager energy of his work. Nudity in comics is fine and good, Crepax is welcome at this household, but there is a "proper" way to do it. To quote Tegan O’Neil in her review of a Corto Maltese volume: “Doesn’t that woman have large breasts in the most literary way?” There is a desire not just for the pleasure, but for an intellectual justification of it. Not just boobs for boobs’ sake5. Well, that is certainly not an issue for Corben. No pretense of intellectualism in Den. That there is no excuse is probably better than having a bad excuse.

It is to be expected. Corben originally sprung from the filthy pool of the alt-commix movement, and swam proudly in its waters — “The time of the underground comix was a Xanadu period for me. I could pretty much do anything I wanted and it would be accepted.” Yet unlike his x-suffixed, x-rated brethren, Corben went on to find mainstream success in both horror and superhero comics. Corben doesn’t appear to precious about his reputation an auteur, though he is undoubtedly is6, working on other people’s creations, with other people’s scripts and taking pride in his work on, say, the Warren magazines just much as he does his creator-owned stuff. That is a big difference between other commix artists and Corben: he values his independence but does not venerate it as the be-all, end-all of creation.

The other big swinging difference is the manner in which nudeness, male and female, is presented in Den. With the likes Crumb, Wilson, Rodriguez, etc., one got the feeling that nudity (alongside the violence) was against — against the mainstream morals, against social taboo, against the censorship of the comics code. They did it because they were told that they shouldn’t. As a result, much of the work of that period has not aged well. Unmoored from the social confines of the day, it appears less hateful against proper targets but simply hateful in a general sense, with women and minorities getting the lion’s share of the damage.

Den, meanwhile, portrays the naked human form for a very simple reason — Corben really likes to draw naked bodies. There’s a certain joie de vivre to Den. Things exist on the page because Corben wanted to draw them. And he wanted to draw them because he enjoyed them7. Crumb knew he was breaking taboos. Corben appears not to have understood that the taboos even existed.

The human bodies in much of Den are not just idealized in the manner of superhero comics or pulp covers by Frazetta, but are taken to the nth degree and beyond. Is Den, the character, actually attractive to anyone? Does a penis the size of bodybuilder’s forearm appeal to the eye? Statistically there's a crowd for it out there. It does not truly matter. The human body in these stories is like an ornate building, an edifice carved in stone. It is not expression of a possibility but of something more abstract. Corben could draw realistic bodies, if nothing else he could make impossible bodies at least semi-plausible, but he doesn’t want to. Den, the character, is a small child’s dream of sexual adulthood; it's Captain Marvel (the Shazam one) with an NC-17 presentation. But this isn’t Mad Magazine, Corben does not wish to mock the fantasy but to embrace it, to see through the eyes of a child.

Growing Pains

None of which allows Den to transcend its limitations. The story is overwritten and under-thought. The characters never achieve any degree of depth. Corben, you would not be surprised to learn, is a better artist than he is a writer. At the same time, the very limitations he possess as a writer are in a direct correlation with his artist-self. Someone else, someone with a more intellectual approach, an Alan Moore or an Eddie Campbell, could write something like Den in theory, but much of the impact would be lost. Even Kirby, a master of unencumbered storytelling, had a better sense of planning for fictional reality and character progression in his Fourth World. Not to mention an inner-sense of inhibition borne out of years in the trenches of the mainstream (and the need to keep a family fed). Den is a man-child, and whatever Corben was in his personal life he wrote with a rare sense of full personal expression. There are no inhibitions to Den, just as there are no inhibitions to Den.

Back to Turner for a bit. I read Franny Moyle’s Turner: The Extraordinary Life and Momentous Times of J.M.W. Turner in preparation to for this piece. Towards the end of his life Turner, for several decades one of the most popular and respected painters in England, became a recluse, losing friends along the way. One former supporter said, “[there] is evidence of gradual moral decline in the painter’s mind.” Moral decline. He no longer wanted to work in a traditional manner, painting the same landscapes and sea-scenes, no matter how good he was at it. The closer he got to the end of his life the more Turner chose to become Turner, instead other people’s notion of Tuner.

In that, I think, Corben is superior to Turner. Reading through Den, a work of staggering highs and lows, I cannot see it as he did. But I can see that Corben always chose to become Corben. I don’t need to like it; but I can respect it. Swing for the fences.

***

The post Giant Sized Man-Child Thing: Thinking through Richard Corben’s <i>Den</i> saga appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment