“Happī mania kanketsu”

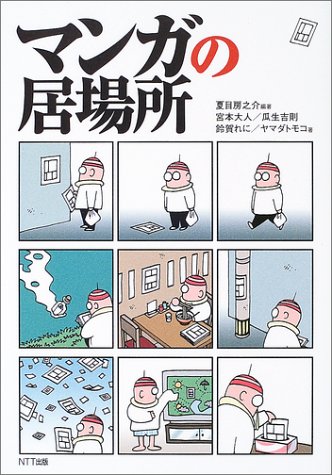

From Manga no ibasho (Where Manga Belongs; NTT Shuppan, 2003), pp. 216-217.

“Please give me a divorce,” says the husband of the main character in the ongoing reboot of Happy Mania (Happī mania), one of Anno Moyoco’s most popular manga. The original series ran from 1995 to 2001 in Feel Young, a manga magazine marketed to mature Japanese female (josei) audiences. Anno’s manga featured one of her most endearing heroines, Shigeta Kayoko, who is manically obsessed with finding heterosexual happiness in the perfect man. If you have read any shōjo manga, what Anno did with Happy Mania was to raise and twist the usual romance angle into dizzying and hilarious heights. In terms of its sheer achievement and impact, critic and novelist Fushimi Noriaki grouped Happy Mania with Neon Genesis Evangelion, directed by Moyoco’s husband, Anno Hideaki, as two of “the most important works generated in Japanese subculture of the [past] decade” of the 1990s.1 But that was 20 years ago. In 2019, Anno Moyoco began to serialize her update to Shigeta's story with the protagonist now in her 40s (arafo or “around 40s”). Go! Happy Mania (a pun on both the English “Go!” and the Japanese word for “post-” or “sequel”) follows Shigeta’s new adventures as she struggles with the question, “Should I have been such a maniac for domestic happiness?” Go! Happy Mania might become Anno's most important work.

In the following brief essay, manga scholar Miyamoto Hirohito describes the 2001 conclusion of the original Happy Mania series, and celebrates what Anno had achieved at that point. Miyamoto also skillfully and concisely details the characteristics of the shōjo manga form, and how Anno repurposed and updated them for new audiences in the second half of the 1990s. Anno had a string of manga hits from the mid 1990s through the 2000s; adaptations thereof into television, anime and film only attest to their power and resonance with Japanese audiences. Following the television adaptation of Happy Mania in 1998, her Sugar Sugar Rune (serialized 2003-07) was made into an anime in 2005-06; her unfinished Hatarakiman (Man-at-Work, begun 2004) was adapted into an anime in 2006 and a television drama in 2007; her gorgeous Sakuran (2001-03) was made into a feature film in 2007. Then, for nearly a decade, Anno was barely visible on the manga scene, save for the irregularly-serialized Memoirs of Amorous Gentlemen (2013-18) in Feel Young.

Miyamoto's essay was first published on August 10, 2001, as part of a multi-author serialized manga column, and was reprinted in Manga no ibasho (Where Manga Belongs), a 2003 collection of those columns by Miyamoto, Yamada Tomoko, Suzuka Reni, Uryū Yoshimitsu and Natsume Fusanosuke (who also edited the volume). These columns were written in a tag-team fashion by each of the five authors from 1998 through 2002 in the evening edition of the Mainichi Shinbun (Daily News). Originally the publication schedule was bi-weekly, but due to its column's popularity, it began to be serialized weekly from 2000; then, in 2002, it went to a monthly run in its final year. We thank Miyamoto-sensei for his permission to translate this essay.

-Jon Holt and Saki Hirozane

* * *

Because it ended up becoming a big topic for last month’s column, I thought I’d start off with it here. I’m talking about the finale and completion of Happy Mania (Happī mania). We must pause and celebrate what creator (sakka)4 Anno Moyoco has achieved in this work alone, a work that easily straddles multiple generations. What else could this column be about this month?

Happy Mania achieved a seven-year sting of popularity serialized in a manga magazine whose target demographic is women in their 20s; it also was adapted for a television series. Moreover, it has been a work that has achieved a sizable reputation throughout the manga world.

Its story can best be boiled down to this. The protagonist, Shigeta Kayoko, is always on the search for a boyfriend, going from one man to the next, never able to continue a relationship for very long; Shigeta throws herself, body and soul, into the question of how to balance “the kind of happiness that can make my body tremble (furueru hodo no shiawase)” with stability and self-maintenance. I guess that’s the best way to describe the manga.

Much of shōjo manga (girls’ comics) has long operated according to the idea of “surely there is some guy out there who will recognize the good in me (watashi no yosa o mitsukete kureru hito wa kitto iru).” That’s true even for shōjo manga today. The genre has maintained it as part of its core identity—that wish—which always gets granted in the end of every story. Once somebody recognizes the good inside the girl, what results in the “happy end” (happī endo). Moreover, if someone kindly discovers the goodness in the girl, he always continues to see the girl. One means the other. But one must ask: why did it get that way in shōjo manga? In Anno’s manga, what you actually see is the start of something new. She starts with the idea that there could be a type of love where the boyfriend does not necessarily do the kindness of continuing to notice the goodness in the girl. In Anno's work, the girl may be looked after by the man, but no true love results from it. In other words, with Anno, her stories begin at the point where most shōjo manga end.

Of course, there are manga artists who first tread a new “post-shōjo manga” path before Anno. She wasn’t the first. So what made Anno’s work so new? The question is still worth asking.

All of those artists working in the “post-shōjo manga” era, in general, do not draw big [sparkly] eyes. Nor do they draw the eyelashes too much. For them, the issue is not how much of the face to show, but rather what is the important part to bring out in the faces of their characters.

But Anno is different on that point. In her drawing, she seems to lead the charge resisting the trend to get away from “shōjo-mangaesque” eyes; in fact, over time she has gradually increased the size of her girls’ eyes as a way to establish her own drawing style (Figure 1). Of course, this is not a throwback to the classic shōjo manga. She is making it work in the complete opposite way.

Normally, with eyes in shōjo manga, the bigger the artist draws them with care, the more the character then demands the reader to “look at me.” These are eyes made only to be seen. However, for Shigeta’s eyes in Happy Mania, the bigger her eyes are drawn, the more she sees with them. Indeed, when Shigeta begins to discover a new man for her love life, she will look at him through and through, until she actually, directly perceives how impossible love with him is. Anno divorced her characters from eyes that are made to be seen, and instead she restores to them eyes that see. We really should praise more this manga warrior who stands on the edge of a 20-year old trend in manga.

Bravo, Anno! Bravo!

* * *

The post The Conclusion of <em>Happy Mania</em> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment