A word for Woshibai, then, author of the new collection 20 km/h, the latest Chinese import from Drawn & Quarterly - "anonymous" and "underground," per the publisher, if that designation carries any historical weight outside local market conditions. The question emerges: what exactly does it mean to be an “underground” cartoonist in China in 2023?

I can’t promise that I have a good answer to that question. It makes sense in the west, perhaps, to see a certain kind of political expression as intrinsically “underground” - sardonic, risqué, politically charged in some respects, if also inchoate in others. It’s a model that exists in the context of a relatively open society, even as certain modes of expression are still pushed and flattened towards the edges. But what counts as underground in a closed society? What doesn’t? Speaking as someone with an imperfect understanding of Chinese culture, I can say that it’s not renowned as a society tolerant of dissenting viewpoints, at least in political terms. What does it mean to express dissent in that context?

From what I am given to understand, through a roundtable discussion conducted by Orion Martin of Paradise Systems in Bubbles #17, independent publishing as such is formally illegal in China. In practice, the thriving independent publishing scene exists in a grey area, partially formed by legal technicality and partially enabled by benign neglect on the part of a political apparatus that keeps tabs on the scene enough to be able to assimilate popular trends under official auspices. What independence exists, therefore, appears a fragile allowance granted on the condition that artists remain enthusiastically circumspect.

Woshibai is, above all else, circumspect. There is no explicit messaging here. If you’re looking for broad political agitprop, you’re not going to find it in these pages. Every layer of meaning has been abstracted to the nth degree, and it's not hard to understand why. If you made cartoons in a country where the President is internationally renowned for having thin skin about Winnie the Pooh, you’d probably want to go out of your way to avoid express topicality.

By that same token, as outsiders looking in, it doesn’t make sense to put a lot of emphasis on tendentious political readings of what are, on their face, relatively anodyne cartoons. Look at the first number in the book, “Bridge.” A featureless white figure wakes up in the middle of a long bridge suspended over water. As far as one can see, the figure is surrounded on either end by rows of identical sleeping figures, with no end in sight. And then there is a rowboat in the sky, manned by a crew of four. They spot the figure clambering over the endless rows of sleepers, swoop down to get them, and hand them oars. At which point, having retrieved their man, the flying boat leaves the bridge of sleepers. This isn’t a difficult story, as these things go. If anything, it would be easy to go overboard in terms of ascribing political motivations to a broadly applicable fable. This is where the outsider looking in might lead themselves astray with an overdetermined moral on the nature of a rigorously conformist society. There’s nothing inherently Chinese about the anxious pushback against stultifying sameness. But you can certainly see from a distance how it might be a particular cultural hot button all the same.

What struck me throughout 20 km/h was the degree to which the proceedings resembled a talent far less underground than online: Nicholas Gurewitch of The Perry Bible Fellowship. It’s not just the shape and dimensions of Woshibai’s featureless everyman, a round-headed blank specimen who strongly resembles Gurewitch’s own round-headed blank specimens. There’s something in the sensibility here, influenced at many generations’ remove by Gary Larson: futile absurdity, the human condition hanging by a fraying thread between the Scylla and Charybdis of whimsy and irony. “News Break” shows us a man eating his lunch and watching a news story about an escaped tiger. He finishes his lunch and replaces his tray, but the moment he steps out of the restaurant he is assailed by said tiger, which chases him up a basketball hoop. The scene cuts to later that night, with the man enjoying a fireworks display from the safety of atop the basketball hoop, the tiger resting peacefully on the ground below.

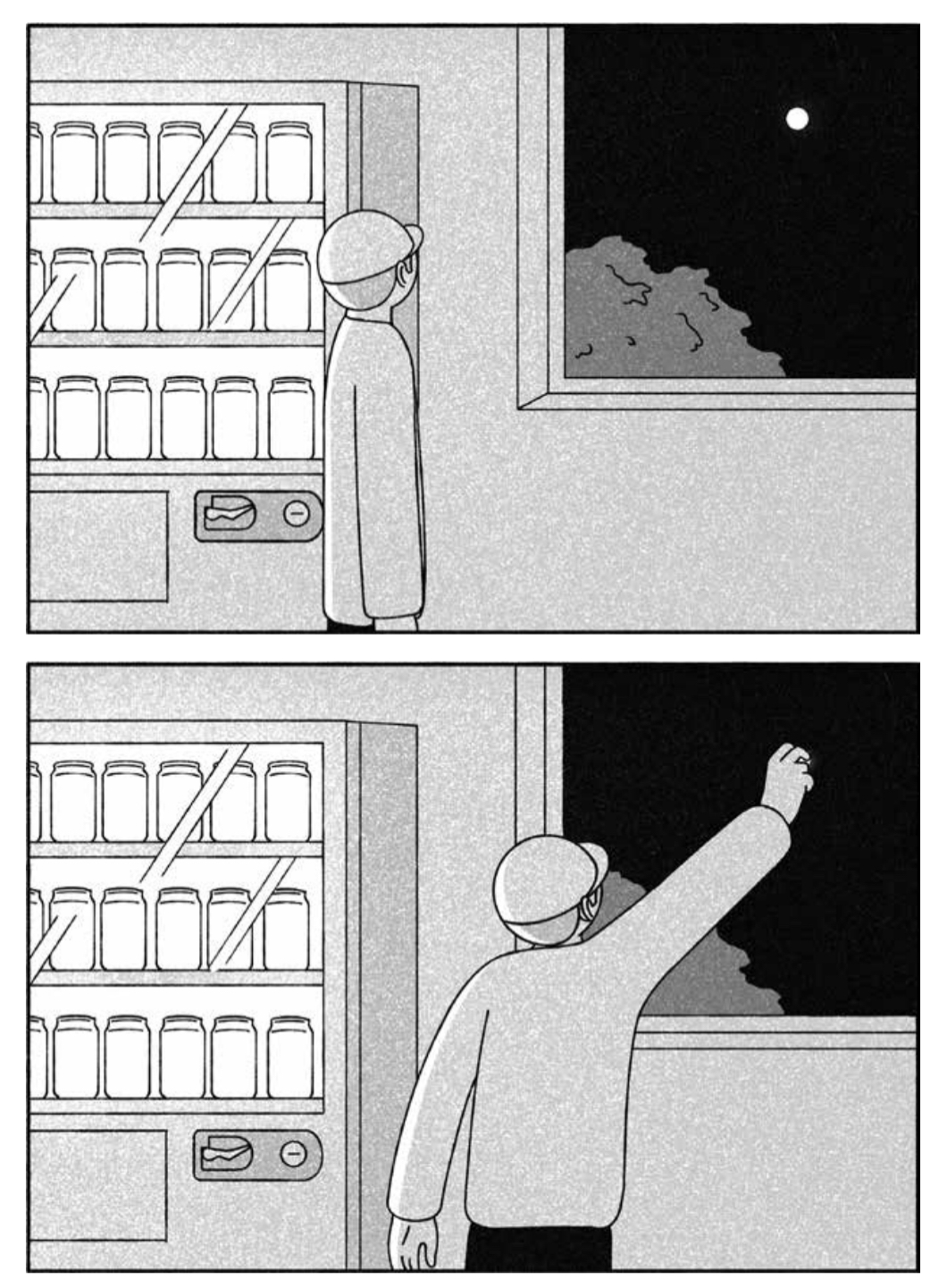

Woshibai is throughout preoccupied by questions of deceptive scale. “New Light” shows a man plucking the distant moon from the sky to use it as a coin in a vending machine, while the very next strip, “Clean Up,” introduces an interstellar janitor responsible for polishing the heavens, who pockets a moon in the course of his duties. Later, “The Collector” shows us a man in a tower plucking shooting stars from the sky and placing them in a glass jar. However, in “0°C” the expectation of an ironic reversal is itself stymied: a snowflake falls on the eyelash of a man steering a row boat across a dark body of water. The falling snowflakes across the water look like a star field.

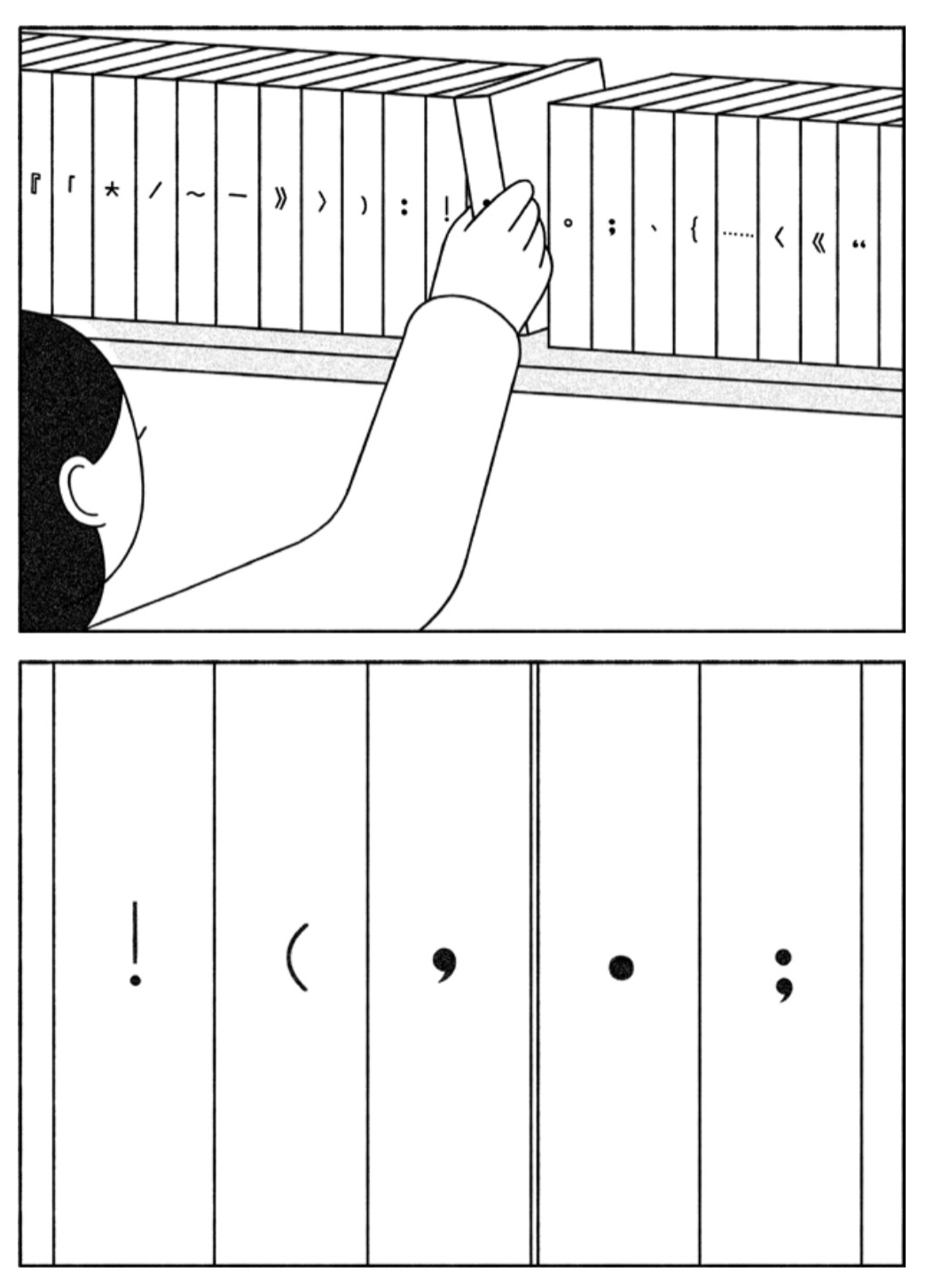

One step up from Woshibai’s blank everyman is a clothed figure, face partially obscured by the bill of their cap. This is a figure of puckish intransigence, as seen in strips like “Rules,” in which our protagonist is seen making deceptively inaccurate rulers by hand before mixing them in with a box of normal, accurate rulers. A few pages later this same figure is shown, in “Petty Theft,” breaking into a succession of houses wherein they rip one page out of the middle of a seemingly random book in each, before returning home, where they fill and bind a book composed of those random pages. Later in the volume, in “Sorting,” we meet a hatless protagonist filling even stranger volumes simply with a catalogue of stolen punctuation marks, cut and pasted from other books to fill journals of purloined commas and semicolons. Futile gestures of defiance, perhaps, but executed with skill and verve. The only available outlets for the conscientious rebel.

The volume’s title sketch, “20 km/h,” is a four-page sequence showing a horse-drawn wagon being pulled down the highway - not by horses, but leashed butterflies. The butterfly appears throughout, a symbol of stymied freedom - “Sweep” is a docent’s daydream at a lepidopterist’s museum, a dream of freedom for a pinned insect. That sense of engrossing futility permeates much of the book: “Void” shows a craftsman painstakingly chopping a tree, cutting and planing boards to assemble a ladder with which to climb up into the sky. But when the sky is reached, all we find is an empty void filled with broken ladders. “Key” gives us a person in a room making keys which keep breaking in the door, leaving no egress from a small cube surrounded on all sides by lush forest. “Jig Saw” shows us a quest across the world for all the scattered pieces of a jigsaw, only to reveal that the final missing piece has been left out by the cartoonist themselves.

As with Gurewitch, and Chris Onstad, and Larson before, there’s an eager utilitarianism to Woshibai’s style. The line longs for the crisp brevity of an IKEA furniture manual, pellucid communication in an era of florid commercialism. It’s a strong style, for all that - portable and legible across the chasm of cultural difference. There’s a great deal of the universal in these stories and sketches, an exquisitely muffled yawp of defiance against a world that offers no better personal outlet than the cudgel of petty irony.

The post 20 km/h appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment