* * *

"We're all art nuts. We're involved with Texas and Japanese esthetics and primitive art. There's also Cubism, Surrealism, Dada and Pop Art. What we do is take all these cultures and smash them all together. We're from a generation of people who are used to switching television channels. What we've done is synthesize all these styles."

-Gary Panter, from a 1987 New York Times report on the success of the first season of Pee-wee's Playhouse

In 1986, CBS' decision to insert the anarchy of Paul Reubens and Pee-wee's Playhouse into the era's relatively bland landscape of Saturday morning cartoons was a pretty big risk.

“I have to confess," Playhouse animation director Phil Trumbo told author Caseen Gaines in the 2011 book Inside Pee-wee’s Playhouse: The Untold, Unauthorized, and Unpredictable Story of a Pop Phenomenon (ECW Press), "[w]hen edits were being put together of the show, I'd see some of them and think, 'Wow, this is just too weird. It's just too funky, it's just too loose.' I didn't know if anyone was going to get it."

While the Playhouse was unlike anything else in the key time slot of 11:00 on Saturday morning, the world of television was already beginning to change. MTV was launched in 1981, and Late Night with David Letterman debuted the following year. The growing presence of offbeat viewing options, many available on cable television, were redefining America's acceptance of non-traditional entertainment and humor. Networks were also facing increasing competition from those new cable outlets for the Saturday morning demographic.

Judy Price was the CBS children's programming executive responsible for bringing Pee-wee's Playhouse to the small screen in those years. "It was getting tougher," she said. "When Nickelodeon came on the scene, networks were only [devoted to children's programming] on Saturday mornings, and [Nickelodeon was] on seven days a week. Plus, they were edgier. The networks were so strait-laced, primarily due to the oversight of the broadcast Standards [and Practices] department, not to mention the pressure groups such as Action for Children's Television (ACT). A real love-hate relationship, to say the least. Couple that with the networks [airing] mostly adult programming, [and] it was hard to even promote our shows. For season premieres, we even resorted to taking ads on Nickelodeon. And let's face it, the networks' priority was not children's programming. Daytime soaps made the money and prime time the prestige. In other words, we got no respect. Pee-wee's Playhouse did get their attention, though, even if the big-wigs didn't get it."

As it turned out, CBS' gamble paid off. It launched a program that was hugely popular across multiple demographic targets; Nielsen ratings for that first season showed that the "half-hour program is watched by 9.3 million people - 6.4 million from 2 to 17 years old and 2.9 million 18 and over," according to a 1987 New York Times report. And it wasn’t just the network that benefited.

"Our strategy was to appeal to the 2 to 11-year olds," said Price. "That's the demographic that our advertisers were after, with the most emphasis on 6 to 11-year olds. The college crowd's latching on to the show was frosting on the cake, but did not add to our coffers - only our hipness. The slightly naughty innuendo and attitude were appealing to them. They got the jokes! Teens, on the other hand, were not fans. My theory is that they were confused by this man-child."

Pee-wee ephemera had existed via its Fan Club ever since the character's first wave of prominence in the early 1980s, but unlike many of the other Saturday morning programs of 1986, there was no Playhouse-related merchandise created for its first season.

"Since toys must be in the pipeline almost a year out from Christmas and to be at Toy Fair in February, there were no products that first year," said Price. "Pee-wee's Playhouse wasn't picked up until the beginning of 1986 and [was] on the air that September. What's astounding was Paul's ability to pull it off in such a timeframe."

But by season two in 1987, by which time production of the show itself had moved from New York City to Los Angeles, any number of Pee-wee related products—toys, dolls, bed sheets, sweaters, pajamas, t-shirts, stickers, trading cards—were available for purchase. And like the Playhouse show itself, these products were chiefly designed by a group of young NYC artists under the direction of Gary Panter and Reubens himself. Cartoonists and illustrators working on Playhouse merchandise included Ric Heitzman, Mark Newgarden, Kaz, Charles Burns, J.D. King, Richard McGuire, Stephen Kroninger, Tomas Bunk, Norman Hathaway and others. When Reubens died of acute hypoxic respiratory failure on July 30th of this year, I reached out to a number of people involved in shaping the Pee-wee empire. In Part One of this series, I spoke with a number of artists who designed the visual aesthetic of the successful television program; in this second and final part, the focus will be on the many functional and ridiculous products created in its wake, including some that never made it to stores.

***

Merchandise based on a children's TV dates back to the earliest days of commercial television; the Howdy Doody show debuted in December of 1947, and it wasn't long before toy companies and department stores were vying to carry replica dolls, toys, licensed clothing and any number of other items. A 1955 Howdy Doody merchandise catalog had 24 pages of products licensed by the show. Reubens was a lifelong fan of Howdy Doody, and had appeared in the show's studio audience—the Peanut Gallery—as a child.

By the mid 1980s, when Pee-wee's Playhouse debuted on CBS, the alliance between licensed products and children's programming was raging. Pee-wee's Playhouse took an unconventional approach to... well, pretty much everything. This included the merchandising of the show.

"Like with everything, Paul was a perfectionist regarding the merchandising," Price said.

One of the most iconic items was an 17" Pee-wee talking doll created by Matchbox, a company best known for its Hot Wheels line of die-cast miniature toy cars. The Pee-wee doll, along with a line of difficult-to-design plush toys modeled after Playhouse characters (and furniture), began selling in 1987. The doll was extremely popular, and designing it was extremely complicated.

"I can't tell you how many heads we went through," Reubens told Collecting Toys magazine in 1995. "It just didn't look like me. It was always supposed to be a cartoon - it wasn't supposed to be me. That was a decision we made pretty early on. But the doll just didn't look right."

It also tended to break pretty easily.

"[Paul] insisted that his doll be a pull string and not require a battery, much to the chagrin of the toy company," Price said. "He did not want kids to have to have a battery to operate."

"They begged me not to use that string," Reubens told W magazine's Simon Dumenco in a 2010 profile. "They begged me.... Even though it wasn't done anymore, I wanted a pull string because it was from out of my past."

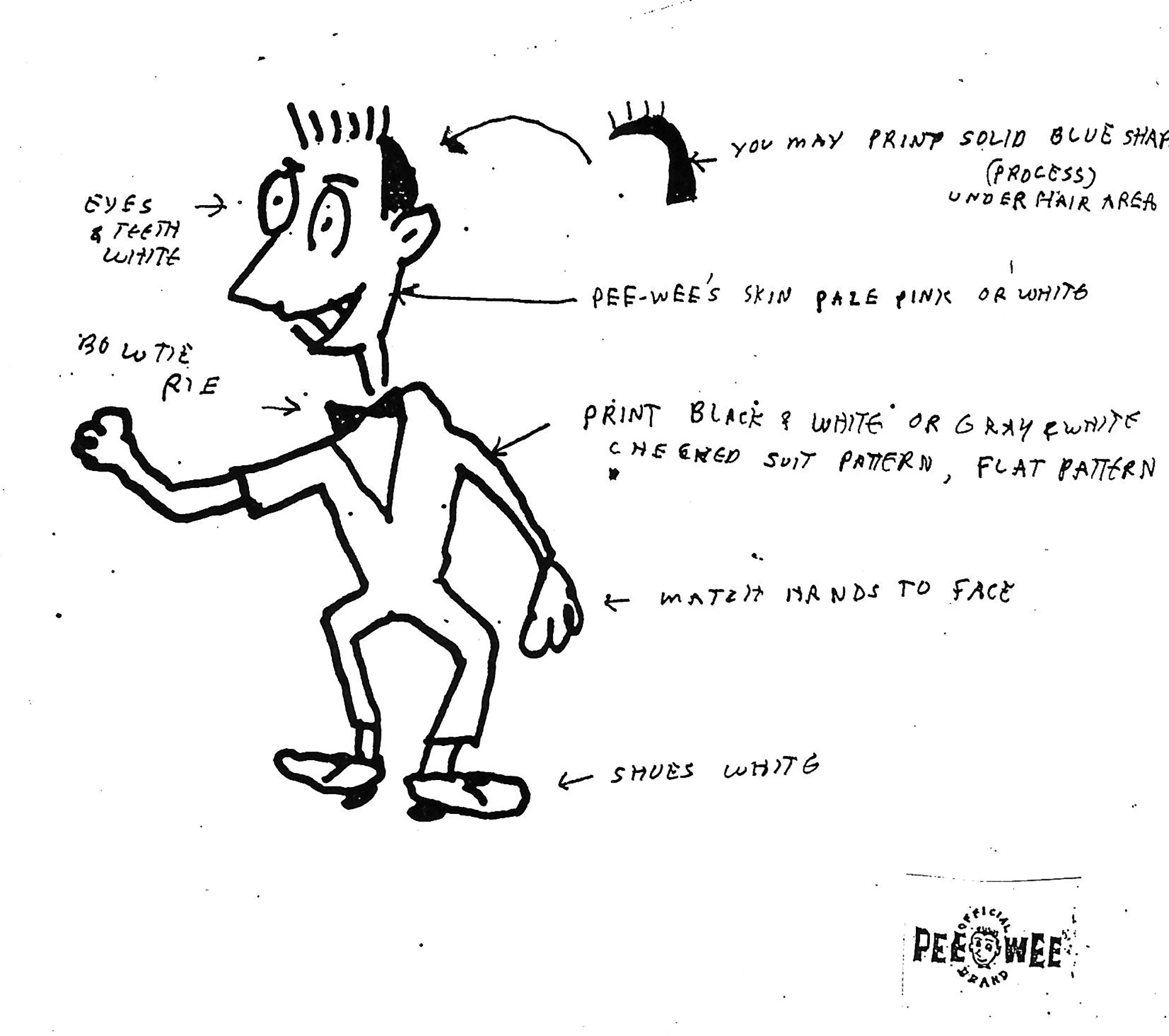

Designing an acceptable-looking doll wasn't the only early challenge for the merchandising companies, so Reubens once again turned to Panter, who had been responsible for the look of the Pee-wee universe since it launched as a stage show in Los Angeles at the start of the '80s, for help in vetting the merchandise approval process.

"After the initial success of the Playhouse [show], companies began approaching Paul to produce 'merch' for the Pee-wee brand," said artist/cartoonist Ric Heitzman, who, along with artist Wayne White and Panter, comprised the core Playhouse design team. "There was a man who was a liaison between the franchisers and Paul who would present him with ideas submitted by merchandising companies. There were designs for cereals, t-shirts, stickers, towels and toys, etc., based on the Playhouse. Paul rejected most of them because the designs were garish misrepresentations of the style that Gary had originated. At that point Gary assumed responsibility as the design director of the Playhouse merchandising."

"All the the packaging was designed by Gary Panter and a group of people he put together," Reubens told Collecting Toys. "It was discussed up front with every licensee that there would be numerous approvals and I would be involved in everything. Even though licensees would agree to those terms, they didn't picture it really happening, so instead of saying, 'We're going to contact Gary Panter first,' they would have their in-house art directors come up with it, and we would have to nip it in the bud. There was a lot of policing involved. I don't think my reputation was so great. But it was about the stuff looking great and the cohesive look."

Mark Newgarden, fresh from co-creating the immensely popular "Garbage Pail Kids" trading card series for the Topps Company—then known as Topps Chewing Gum, Inc.—was among the cartoonists Panter enlisted to help with the design load. Newgarden and Panter both regularly had work appear in the avant-garde comics/art anthology RAW.

"The show was now a certified Saturday morning hit, and the inevitable licensing machine was gearing up," Newgarden said. "There had been a Pee-wee Herman mail order fan club for years (of which I was a card-carrying member), but this was the big time. All the deals went through an entity called 'Premiere Promotions.' Gary Panter was out in L.A. working on the second season and needed help dealing with the onslaught. He initially asked Kaz and I to come up with concepts for Pee-wee-ized versions of some preexisting pachinko-style marble games. Which we did at a small table in my Brooklyn apartment, armed with toy engineer's blueprints and a large stack of Pee-wee production drawings by Gary, Ric, Wayne and others. Finished artwork was created and prototypes eventually emerged, but no such toys were ever produced. This was the first of many such exercises in futility. Pee-wee handbags. Pee-wee talking toothbrushes. Pee-wee bubble wands. Pee-wee soap dispensers. Pee-wee Decorate-It® kits. Companies with names like Coleco Toys, Helm Toys, Aetna (…Aenta?), Paradise Creations and God knows what else. Ideas / sketches / revisions / sometimes even finishes / and then… nada! Or at least I never saw them."

The cartoonist Kaz, another frequent RAW contributor, was brought in early on.

"I can't remember what came first for me, but I'd been visiting Gary Panter in his various studios around Brooklyn for quite a while," Kaz said. "Seeing his paintings, sculptures and sketchbooks was always inspiring, and he was one of the sweetest guys and very generous with his time and ideas. I love the guy! So, at some point he asked me to help out with art on some of the Pee-wee licensing that was coming in hot and hard. I just aped his Pee-wee art style (which was not as easy as it looked). I did all the flat art on the inside of the Playhouse Playset. I did some art when they expanded the Pee-wee Colorforms set by adding two wings, thereby making it 'Deluxe.' A keen eye will see my cartoon character, Little Bastard, sitting on Pee-wee's bed on that art."

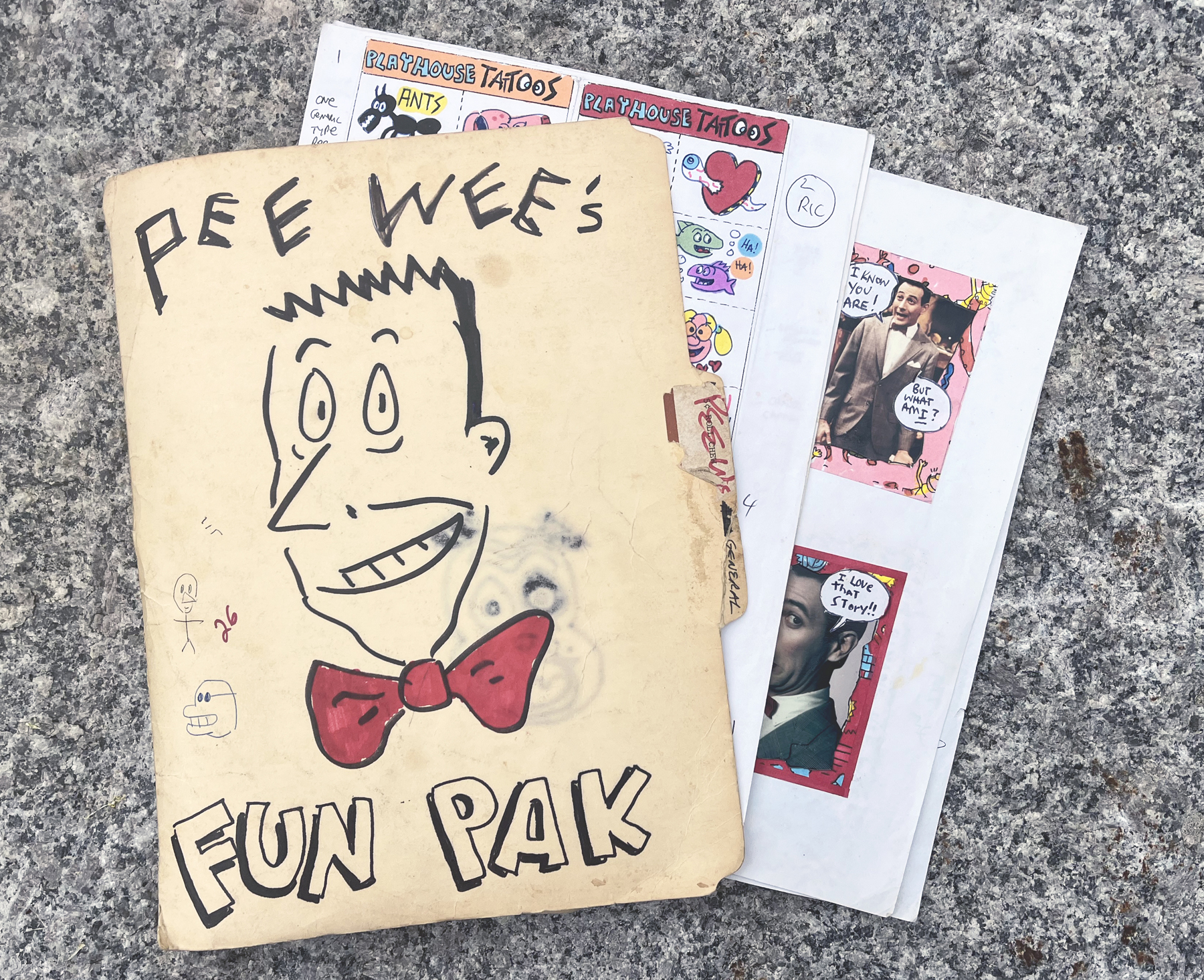

"In 1987, through Gary Panter and Mark Newgarden, I worked with Mark on the Topps Chewing Gum's 'Pee-wee's Playhouse Fun Pak'," Kaz continued. "I remember going into Topps' offices every day for a few weeks. At the time, Topps was in a grimy industrial waterfront neighborhood in Brooklyn that was not a good place to be after dark. Mark did the bulk of the writing and editing on the "Fun Pak" as well as drawing. I wrote and did a bunch of drawings (in the Panter style). There was a lot to do, so some of the art was freelanced out to other cartoonists. Trivia: I got my full Lithuanian first name [Kazimieras] on the back of one card!"

One of the most ambitious of the licensed products was the "Pee-wee's Playhouse Fun Pak" series of trading cards, activities and stickers for the Topps Company, purveyor of candy store staples such as "Wacky Packages" and the aforementioned "Garbage Pail Kids." The project was overseen by Newgarden, a veteran of the bubble gum trade. In the space below, he shares his memories of the project in his own words.

(editor/writer/creative director, "Pee-wee's Playhouse Fun Pak")

Pee-wee came full circle for me in 1987 when Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. of Brooklyn, NY decided that the world was finally ready for the official Pee-wee's Playhouse trading card set. I had been working in the New Product Development department at Topps on odd (or even) weekdays since 1983, and had established enough cachet to take this project and run. Over the decades Topps had produced sundry "grab-bag" products containing a variety of paper novelties, and Pee-wee seemed like a good fit for that approach. Both Gary and Paul were anxious to recycle some favorite Topps memories of their 1950s & '60s childhoods.

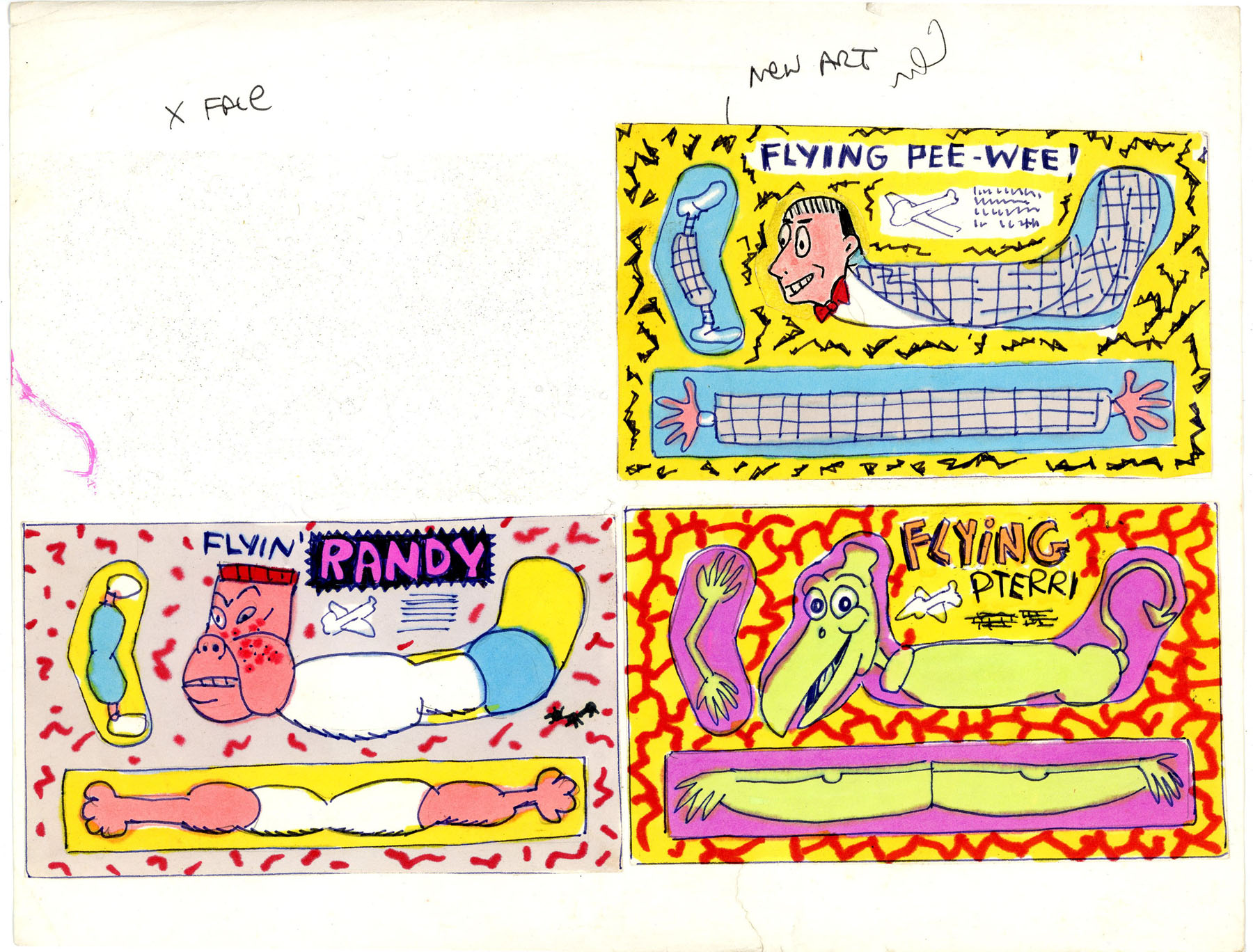

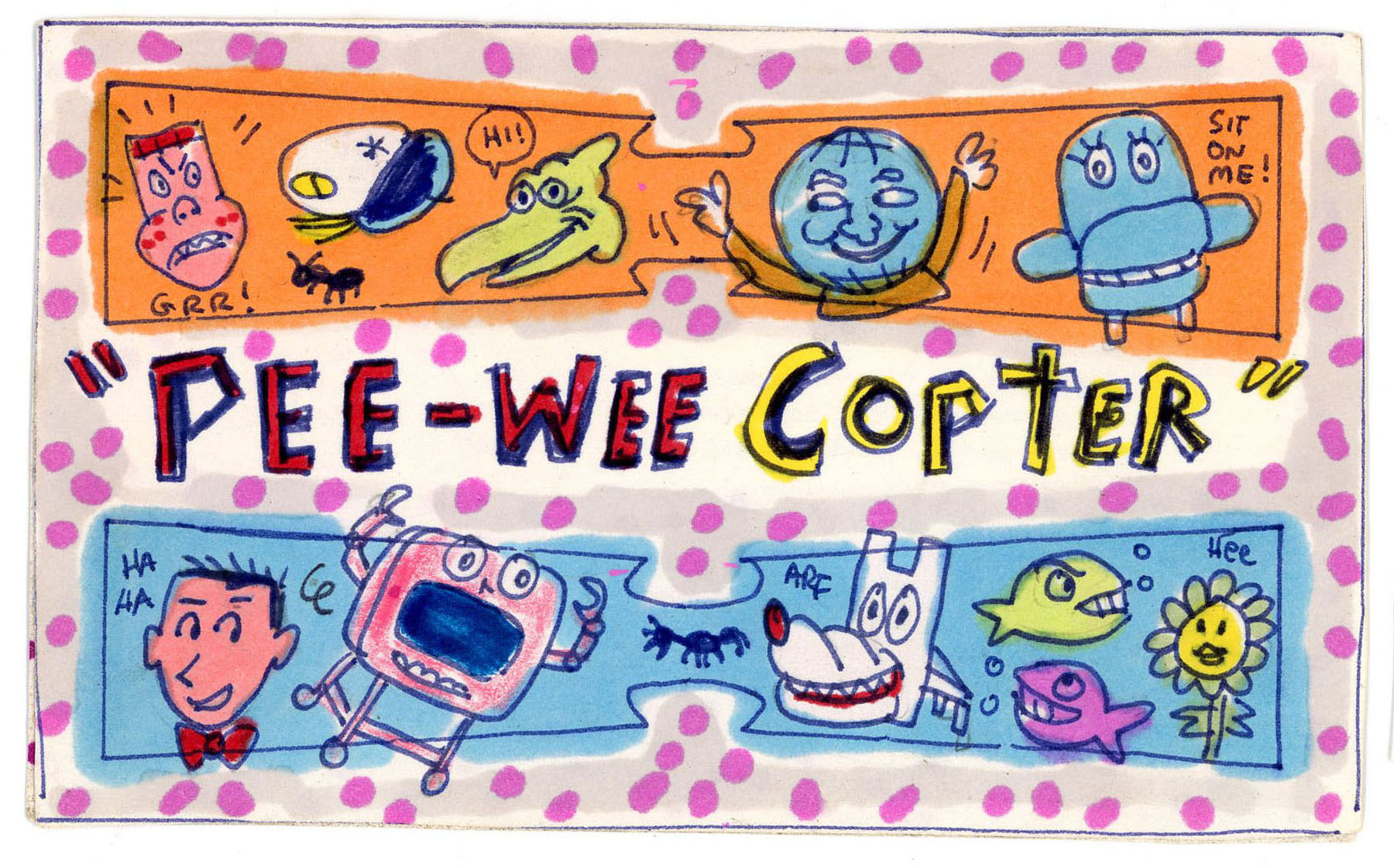

Paul wanted tattoos "very badly," and that we could do. However, we couldn't include some of the old Topps Universal Monsters images that Gary would have liked. In the end we were able to resurrect a slew of formats from Topps' past, including trading cards, stickers, tattoos, lenticular "wiggle pictures," flip books, die-cut activity cards, gliders, copters, disguises and "foldies," among other gimmicks. Kaz and I wrote and roughed out color sketches of the whole shebang onsite at Bush Terminal. Alison (Chairry) Mork captioned production stills with authentic script dialogue. It was an insanely complex product with dozens of moving parts, multiple suppliers, and a formidable amount of deliberately gnarly artwork that needed to conform to exacting technical specs.

In the words of Topps historian David Hornish: "In 1988 Topps came up with one of the most innovative sets they ever produced, right up there with 'Pak O'Fun' and 'Laugh-In.' Pee-wee's Playhouse must have been a risk as the show was mid-run in 1988 but that did not stop the creative team from going bonkers."

It was decided early on that, like the show itself, the product should feature a broad array of clashing graphic cartoon styles, rather than just the faux-Gary ratty linework that Kaz and I channeled for some of the previous merch. Artists who contributed to the "Pee-wee's Playhouse Fun Pak" comprise a rogues' gallery of 1980s NYC alt cartoonists and illustrators including: Charles Burns, J.D. King, Ric Heitzman, Richard McGuire, Tomas Bunk, Stephen Kroninger, plus Kaz and myself. Vintage artwork by Topps icons Basil Wolverton and Norman Saunders was also woven into the set.

Comps and copy for every last element was assembled, and that November I was dispatched to L.A. to obtain Paul's blessings. We sat alone in his office for an entire afternoon and then part of the next as he pored over every single component in detail. His notes were decisive, yet reasonable: "Make face closer to puppet. Include a caption in Spanish on every tattoo sheet. Spell Chairry with 2 Rs. No jewelry. No chocolate. No smoking monkeys. No Hoboken. Do NOT include Indians or safety pins!" Later I was taken for a very L.A. showbiz limo ride (to nowhere) by Paul's business manager, who spun tales of fabulous things in the marvelous Pee-wee future; not a one of which ever transpired.

In the late '80s, the department store JCPenney began selling a line of official Pee-wee Herman clothing products—pajamas, slippers, t-shirts, jeans, sweaters, socks, etc.—and even opened a small department called the Pee-wee Store. This expanded the brand's merchandising further, so Panter called in others to help with the workload, including Newgarden and art director / design historian Norman Hathaway.

"Paul signed a deal with the JCPenney company late in the run of the show," said Newgarden. "They were primed to produce a shit-ton of Pee-wee apparel and merch."

"Paul implicitly trusted Gary's judgement for anything visual and was like, '[Gary] is the guy and I trust him,'" said Hathaway, who designed a number of the JCPenney projects. "And so, he just kind of turned all the merchandising choices completely over to Gary. And what was difficult for Gary is that the people that he was having to deal with were... pretty much the lowest life forms on the planet. They were just like, hey, I need! I need! I need sleeping bag artwork or whatever. And there'd be lots and lots and lots of projects... so Gary asked me to help him. And so I came to New York for probably about five days or something and stayed with Gary and then just went to work. I kept on asking him for a little bit more guidance, or 'What about this? What about that?' And Gary was just like, 'I trust you, just go ahead and do it.' It was very, very open."

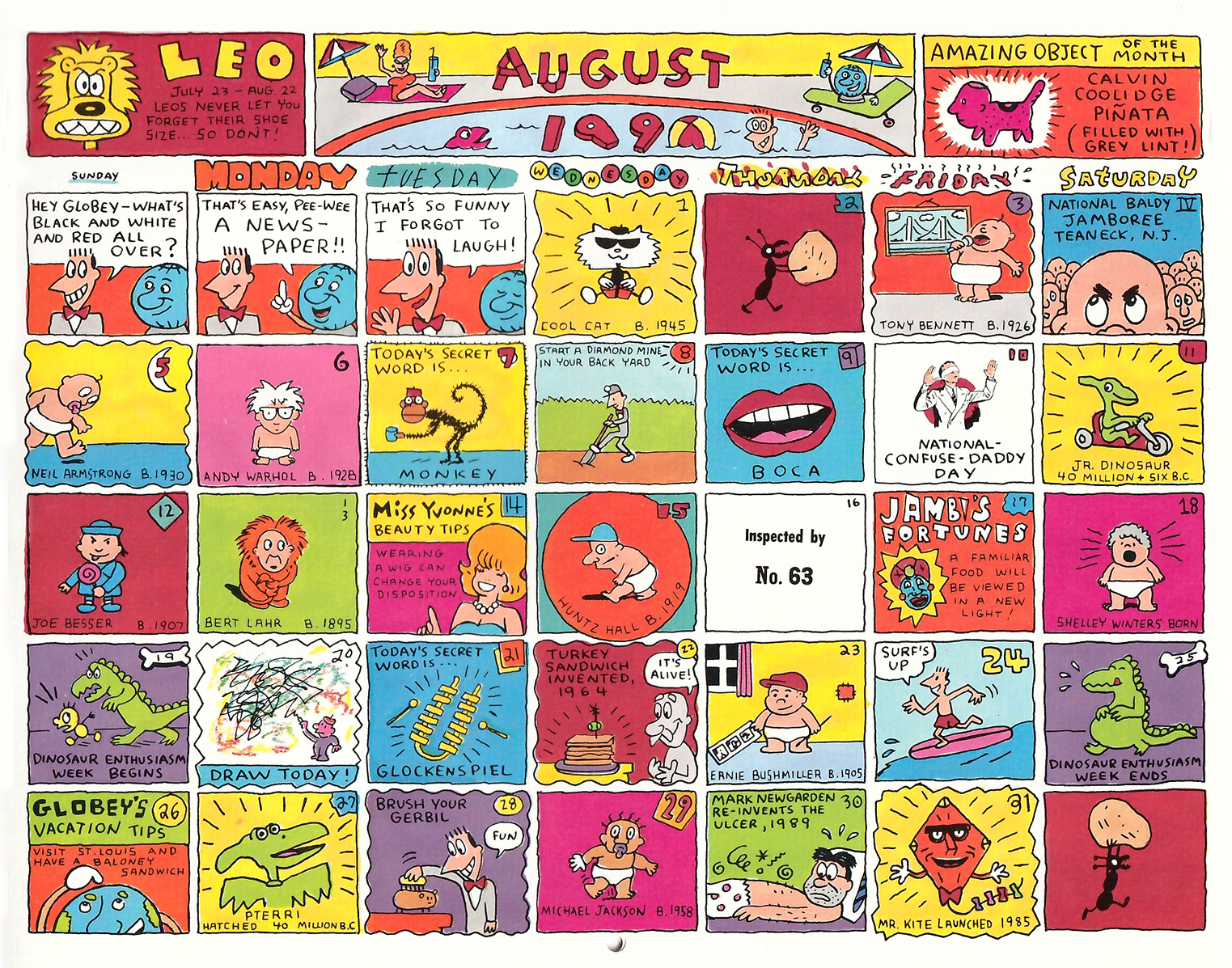

Among the projects that Newgarden produced for JCPenney was a 1990 Pee-wee comic strip calendar.

"The 1990 Pee-wee's Playhouse calendar project fell into my lap, probably on the basis of the [Topps] 'Fun-Pak'," Newgarden said. "My concept was a cartoon a day for each day of the year, sometimes using the calendar grid as comic strip panels. This premise was based on a very psychedelic calendar that I was given (and loved) as a kid. The budget was very reasonable, but the timing wasn't; they needed it completed and out the door, yesterday. [Fellow RAW cartoonist] Richard McGuire gamely joined in, and we nearly worked around the clock on that damn thing. My sister Anne assisted with the coloring. And we did get it out the door, via time travel. Paul was happy and gave an unexpected call. 'I’m happy.' He sounded like Droopy. JCPenney actually provided an art credit on the back of their printed calendar, which was rare in those unenlightened days of anonymous merch content elves. I later revived that format for Nickelodeon Magazine, where the same sort of comics calendar appeared every issue for the first year or so of that publication's lengthy run."

In addition to the Topps work, Kaz also designed some of the products, including a very popular Playhouse-themed set for Colorforms, sold at JCPenney and other outlets. He also designed some household products.

"Probably the weirdest thing I did was design the Pee-wee Herman kids' bedsheets," Kaz said. "I remember going to the bedsheet offices in the garment district. I must have looked pretty grungy because the two guys running the company really talked down to me, 'Do you even know how to do repeating patterns?' I shrugged. 'How hard can it be?' When I asked for more money than they wanted to pay they got freaked out. But the point man on all the Pee-wee projects was Gary Panter. They called him right in front of me to complain and he said, 'Pay Kaz whatever he asks for.' Man, they were pissed! But I got paid!"

For Newgarden, the strangest experience involved socks.

"I once got a random call from an irate sock magnate who had flown to NYC and who needed to immediately meet with somebody, anybody, about the pressing matter of Pee-wee Herman socks," he said. "I had no idea what it was all about, and still don't to this day. But he was insistent. I don't know why, but I was eventually cajoled into a meeting with the out-of-town sock man who apparently believed my role was to congratulate him and greenlight his proposal of printing a photograph of Paul on his socks. He was not happy when I told him that he would likely have to shell out for custom Pee-wee designs, whether by me or anybody else. And our meeting was abruptly terminated when I let him in on the ground floor of my million-dollar Pee-wee 3-D sock idea of mismatched red and blue sets. Were there ever actually Pee-wee socks? And if so, did they match? I have no idea."

There were many more items that were designed, but never reached production. As Panter remarked in Part 1 of this series, "We were involved in many attempts at projects that failed to materialize. There could have been many more amazing products from Paul if merchandisers had listened to him closer."

"The good thing about Paul is that there were a lot of opportunities for him to exploit [Pee-wee] financially that were turned down," Hathaway told me. "Like [Pee-wee] breakfast cereal... if he disagreed with the manufacturer about whether they were were doing things the right way, whether it was right for kids, then he wouldn't do it. That's pretty rare these days.... He wanted to do a cereal, but he didn't want sugar in it. And they just wanted to do like a shitty cereal, so... but the idea for the commercial was one of the funniest things I've ever heard."

"So my cereal was going to be called Pee-wee Chow," Reubens said in a 2011 episode of NPR's Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! radio program. "I actually talked the Purina Company into doing my cereal. And it was going to be the first time that they ever allowed the checkerboard to be put on something other than pet food.... And the commercial for it was going to be a mom, a 1950s mom pouring a bowl and putting it on the floor and kids, like, crawling up [like dogs] and eating it.... But it turned out, kids didn't like it. They wanted a sweeter cereal."

Sales for all Pee-wee merchandise abruptly halted following Reubens' arrest in a Florida adult movie theater in July of 1991, after which he was charged with indecent exposure. Reubens pleaded no contest and was ordered to perform 75 hours of community service. At the time, many rallied to Reubens' support, and while today the resulting outrage can seem pretty ridiculous, in 1991 the incident was major, career-damaging news.

"Although Paul's incident involved only him in an adult movie theatre, children's television stars have to be squeaky clean. (I wish our politicians were held to the same standard!)" said Judy Price. "His mugshot alone was enough to scare any parent. When the news and his mugshot flashed on my television screen that Saturday night, I shuddered. I did not get a good night's sleep, as I knew what was to come. I felt great dismay with what was always incorrectly reported. We did not cancel the show after the incident. It was not coming back in 1991 because Paul did not want to do it anymore. We simply pulled the remaining reruns in August. Period. Even so, Paul's legacy speaks for itself. Pee-wee's Playhouse attracted some of the greatest creative talents of its time. I am still amazed at Paul's vision and his devotion to the art of entertainment."

"Regarding his scandal," Gary Panter said, "I will repeat that the scandal was and remains the scandal of the hypocrisy of America's puritanical confusion and purposive control mechanisms advanced by craven and frightened people. Humans are sexual or we would cease to be. Paul forced a queer spirit into the light out of forbidden territory and was punished by the mechanisms of sensationalism. That was a great and pitiful shame.

"He cared deeply about children and their fates and was very responsible in what he would allow to be marketed to children. He could have made a lot more money if he had not cared so much. It is overlooked that he spent years meeting dying children whose last wish was to meet Pee-wee and it took a psychic toll on him, I believe."

As Reubens told Vanity Fair's Bruce Handy in 1999: "Jeffrey Dahmer's story broke the same time as my story, and for a week I was leading the news, followed by Dahmer eating people, boring holes into their heads and turning them into zombies. It was... just so bizarre."

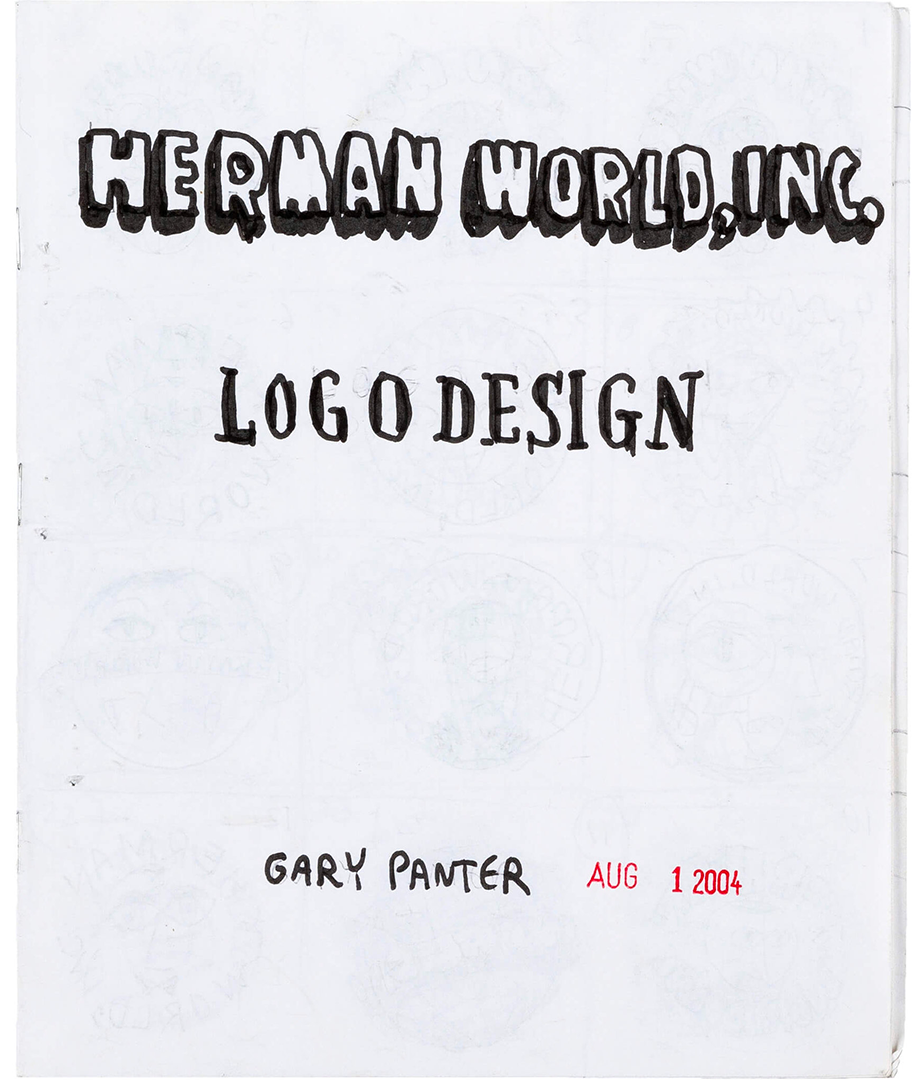

In 2002, Reubens was arrested again when police seized a collection of objects including vintage erotica from his Hollywood home; included in the haul of tens of thousands of items were several that were alleged to contain "material depicting children under 18 engaging in sexual conduct." The charges were dropped in 2004 when Reubens pleaded guilty to a lesser obscenity charge. Later that year, Reubens told Entertainment Weekly that the images were "Really camp, kitschy, funny stuff from the '40s, '50s, or '60s. Ninety percent of anybody off the street who looked at the stuff would burst out laughing and say, 'You're kidding me.'"

"You can say that I'm different, that I'm freaky, that I'm weird - you can say lots of stuff about me," Reubens said. "But you can't say I'm a pedophile. That's just not a part of who I am. I am not a child pornographer."

"It's like getting a job in a sandbox, but they won't let you out. And they beat you..."

-Gary Panter, from the 2012 film Beauty is Embarrassing, a documentary about artist Wayne White, who, along with Panter and Ric Heitzman, served as the core designers for Pee-wee's Playhouse.

By the time of Reubens' arrest in 1991, not only had production on the Pee-wee's Playhouse show ended, but merchandise sales had also dropped steadily.

"I'm not sure the scandal was responsible for the merch ending," Judy Price recalled. "It had pretty much waned the last year of the show. Paul never pushed the merchandising that much and slow-walked approvals, much to the chagrin of his management and the toy companies.... After the third season, Paul did not want to continue [making new episodes of the show]. He wanted to move on. I made him an offer he couldn't refuse by ordering two seasons' worth so he could produce them back to back without the usual year in between. By doing this, he'd also have enough episodes for a package for syndication. He agreed to that. The fifth and final season then started in September 1990. Therefore, in the spring of 1991, when the new fall schedules were announced, Pee-wee's Playhouse was not on the schedule for 1991, by his choice. When the incident happened in [July] 1991, the Playhouse was in reruns with only a few more weeks to go until the fall premiere of the new schedule. Because of the incident, we had no real choice but to remove the Playhouse for the remaining weeks. If we hadn't, our affiliates and advertisers would have dropped the show anyway."

"After five seasons of the CBS show, I was so exhausted," Reubens told the actor Paul Rudd in a 2009 profile for Interview magazine. "I needed a nice big break from the character, and I took it."

Panter was also burned out by the experience.

"Designing stuff is fun," he said. "Getting paid for doing it is not much fun, as justice is not done. For example: I got my friend Rick Potts to design the helmet that Pee-wee wears as he exits the show each week. There was no way Rick was going to get a cent from toy versions. The same goes for all the other design work - Wayne [White's] puppet designs, Ric [Heitzman's] food in the fridge designs, Phil Trumbo's dinosaur design, etc. I stayed on directing toy design for 50 companies for a year with an expectation that it was a way to participate in merchandising, but it was not really to be. The accounting was a big shock and I resigned. The story is too exhausting to tell. Paul thought I got paid enough. To me that was a bad joke considering the ways and means and amount I received. Had I known the outcome I would have bailed. The Hollywood experience burned me out. I ran out of psychic space for the PW show. Paul never understood that. Designing the show was a privilege and dream come true and the fellowship priceless. Dealing with Hollywood was not much fun but an education with a very high cost."

The look of the show really had a lot to do with an artist named Gary Panter, who designed the original stage version of it and designed much of the-- was really the overall production designer and created the look of the show, the television version of it. He was somebody who, when I was really creating that character in the early days of Pee-wee Herman, was kind of like the punk scene in Los Angeles, and he was kind of one of the premier, like, punk artists, and I had seen a lot of his work. He was in a publication called the LA Weekly.... And I'd seen a lot of his work, and I loved his work. And I contacted him and asked him if he would do a poster for a show that I hadn't created yet. And he said, well, why don't I do the poster and-- well, actually, he said, let me come down and see what it is. So he came down and saw me in the Groundlings show where I had my little 10-minute Pee-wee thing, and came backstage and said, I'd love to do it, but why don't I do the whole thing? Why don't I design the sets and the puppets and everything? And I said, yeah, great.

So he designed that. And then when we got the deal with CBS a few years later to do it as a real television series, he came on board. He was the first person I hired and said, you know, you've got to do this set. So it was-- I mean, the rest is history, I guess. But, you know, I think it's probably the most amazing aspect of the show, in my opinion, is the design of it. It was just so startlingly incredible in my opinion.

-Paul Reubens, interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR in 2004.

"[I]t’s a complicated story," Panter told William Van Meter in a recent Artnet interview. "But it really has to do with just showbiz, you know? I don’t really want on my gravestone 'Designed Pee-wee's Playhouse.' It was a dream come true. And that's one thing that drove me and Paul apart was he kept wanting to work on projects. At a certain point, I just said, let's just be friends, you know? And he had a hard time accepting that."

"Anybody who doesn't know Paul, it's hard for them to think of him as a real person," Playhouse designer and puppeteer Wayne White added, in that same interview. "Pee-wee Herman is such a complete reality. It's strange for people to think of Paul as a human being, as a real person. But working around him was just like, this sounds cliché, but man, it was a blast. I mean, I got so spoiled. It was a dream fucking job. I didn't have any responsibilities other than to be creative. I was a child. I wasn't an adult at all. That was handled by the producers and the directors and the assistant directors and the cameramen and all that. We would just play like idiots. It's almost embarrassing how irresponsible I felt at the time, you know, and everybody indulged us. We would just sit around, and smoke weed all day, laugh, and it was just fucking incredible. Just the best job you can imagine."

"I loved Paul," Judy Price said to me. "He was a creative genius. Extremely easy to work with, although demanding on a creative level. He knew what he wanted. We never had any disagreements and he never made any unrealistic or star-type demands. I still received his annual Pee-wee Christmas card and an email birthday greeting every year. After all this time! I wouldn't be surprised if a card still comes this Christmas. That would be so like him. I was shocked and grieved his passing."

"There were numerous other projects, mostly for JCPenney, as the series wound down," recalled Mark Newgarden. "Sometimes I'd be working on things without ever knowing what they were, and other times mentally erasing them on contact. I'd occasionally visit Gary in his studio, which was on a dodgy warehouse bock with cobblestone streets near the foot of the Manhattan Bridge (now gentrified DUMBO). We'd ostensibly 'work,' which mostly meant listening to some very eclectic musical selections and talking comics and movies for hours on end as we traded drawings back and forth. I didn't often partake in Gary's weed, but I recall a night that I did. Yet another set of drawings of the Playhouse cast emerged with especially thick and funky brushwork. Gary never told me why we were doing this and it never occurred to me to ask him... a decade later I did a double take while passing by the late, great 'Love Saves the Day' vintage shop on 2nd Ave in the East Village. Those giant life-sized Pee-wee P.O.P. cut-outs in the display window looked I like I must have drawn them… or re-drawn them? Kinda? Sorta? But wait… did I? I guess… maybe? (And since then, over the years, I've seen those drawings pop up on all sorts of merch, right up until today!)"

"I honestly don't think Gary needed my help at all," Newgarden continued, "but I also don't think he wanted to face those characters alone again, for the 6,000th time. After the show ended I fell out of touch with Paul, except for his annual Christmas cards which showed up like clockwork for decades. He was always depicted in costume at the height of his fame, forever young. I labored on his tchotchkes for years, but like the Wizard of Oz, Paul largely remained the man behind the curtain, briefly poking his head out to weigh in on some pressing Solomonic decision, and then vanishing off into a Pantone #528c cloud. I wish I had made an effort to get to know him better, but that’s not something you easily do with movie stars. Paul Reubens was a charismatic performer, a creative and eccentric guy, and an absolute original. He will be missed."

"Paul Reubens' creation continues to be an inspiration," said Kaz, who went to on become a key contributor to the world of SpongeBob SquarePants. "[SpongeBob creator] Steve Hillenburg has expressed how Pee-wee was one of the inspirations.... And as one of the developers, writers, and story editor on The Patrick Star Show, you can see how inspired the crew and me are by Pee-wee’s Playhouse in Patrick Star's silliness and the weird house he lives in. Paul Reubens is dead but Pee-wee Herman lives forever!"

The post The Artists and Cartoonists Who Designed Pee-wee Herman’s World – Part Two appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment