Brian “Box” Brown, a specialist in biographical comics in recent years, has a new book out from First Second about the capitalistic, predatory precedent set by the Masters of the Universe franchise: The He-Man Effect: How American Toymakers Sold You Your Childhood. The first thing that struck me about it as a longtime fan of Brown's work was cover quotes from famous nerd Patton Oswalt and Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff. Oswalt calls the book “universal and poignant” before quipping “I wish I didn’t have to take the book out of the wrapper. I like my collectibles to be pristine,” while Wolff writes, “[h]ere is an expert unafraid critically to face the social impacts of the industry he knows from the inside.” Together, these quotes do a lot to represent both Brown’s latest book and his current place in comics and politics.

Brian “Box” Brown, a specialist in biographical comics in recent years, has a new book out from First Second about the capitalistic, predatory precedent set by the Masters of the Universe franchise: The He-Man Effect: How American Toymakers Sold You Your Childhood. The first thing that struck me about it as a longtime fan of Brown's work was cover quotes from famous nerd Patton Oswalt and Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff. Oswalt calls the book “universal and poignant” before quipping “I wish I didn’t have to take the book out of the wrapper. I like my collectibles to be pristine,” while Wolff writes, “[h]ere is an expert unafraid critically to face the social impacts of the industry he knows from the inside.” Together, these quotes do a lot to represent both Brown’s latest book and his current place in comics and politics.

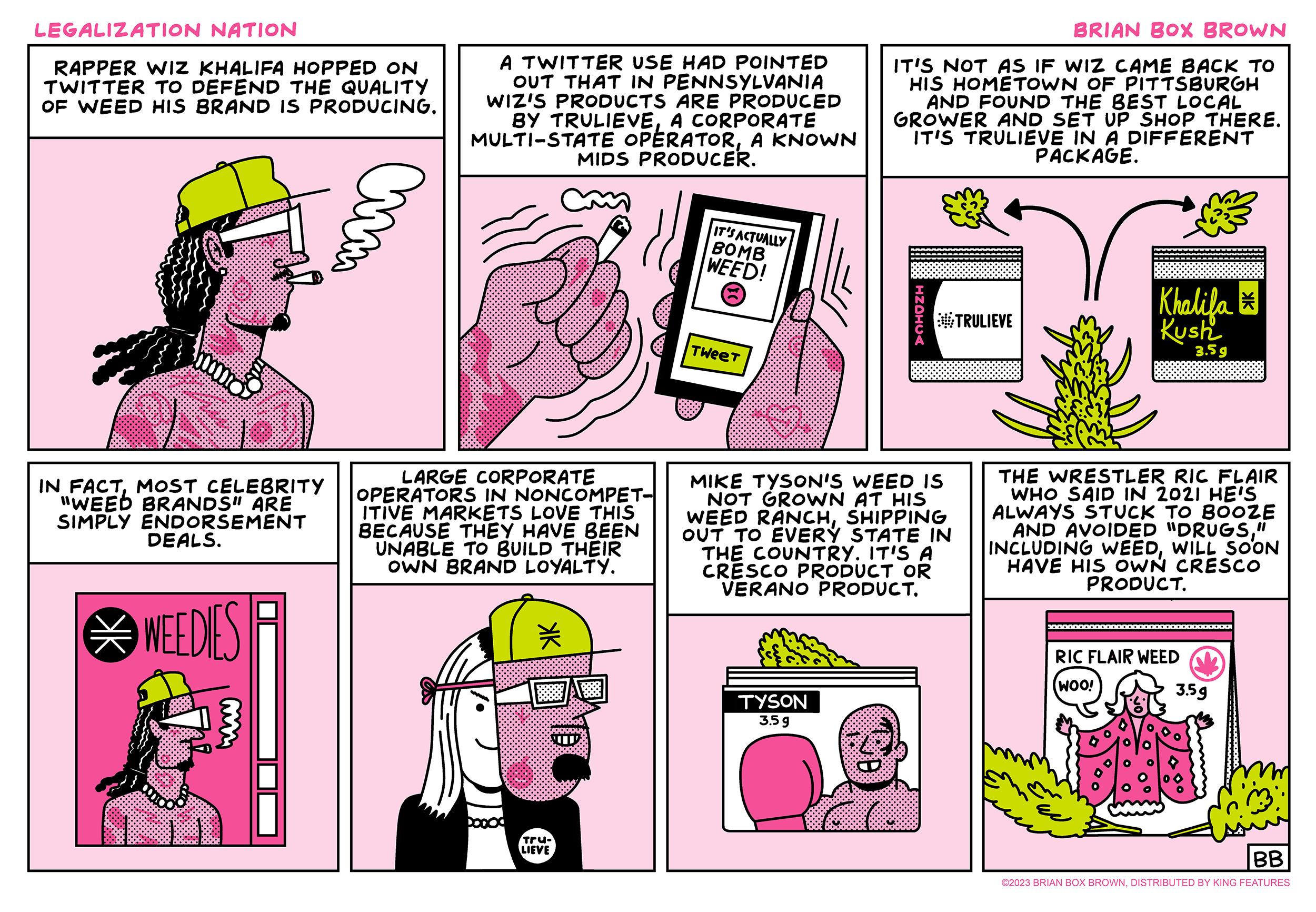

Brown, who also writes and draws the reportorial Legalization Nation weekly strip about marijuana law, has been a dedicated comics professional for over 15 years; more recently, he has become a type of journalist-polemicist who tells stories about social justice and pop culture, wedding a not-entirely-cynical enjoyment of the stuff to a more sophisticated urge to acknowledge the systemic rot that poisons 'geek' art and society at large.

This is something I happen to find profoundly relatable. Following Brown’s career has helped me figure myself out.

The Philadelphia-based print and web cartoonist became known to a wider audience after First Second's 2014 release of André the Giant: Life and Legend, a graphic novel about the famously large and charming professional wrestling star. First Second continued publishing books of his along similar nonfiction lines, including 2018’s Is This Guy For Real? The Unbelievable Andy Kaufman, which received an Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, and 2019’s Cannabis: The Illegalization of Weed in America, a notable recent step away from pop culture.

Years ago, at a toy convention in Philly, Brown found himself struck by all of the commerce surrounding him.

“It occurred to me that all of these people were still benefiting from advertising that was done in, like, 1982,” Brown told me. “And these people are still buying all this stuff.”

He embarked on an extensive research process that included numerous personal interviews. It took Brown until the end of 2019 to finish The He-Man Effect. Then the COVID-19 pandemic happened, and then First Second decided to push forward with a comic biography of Vladimir Putin that Brown collaborated on with writer Andrew S. Weiss; as a result, The He-Man Effect didn’t release until July of 2023, over three years after its completion.

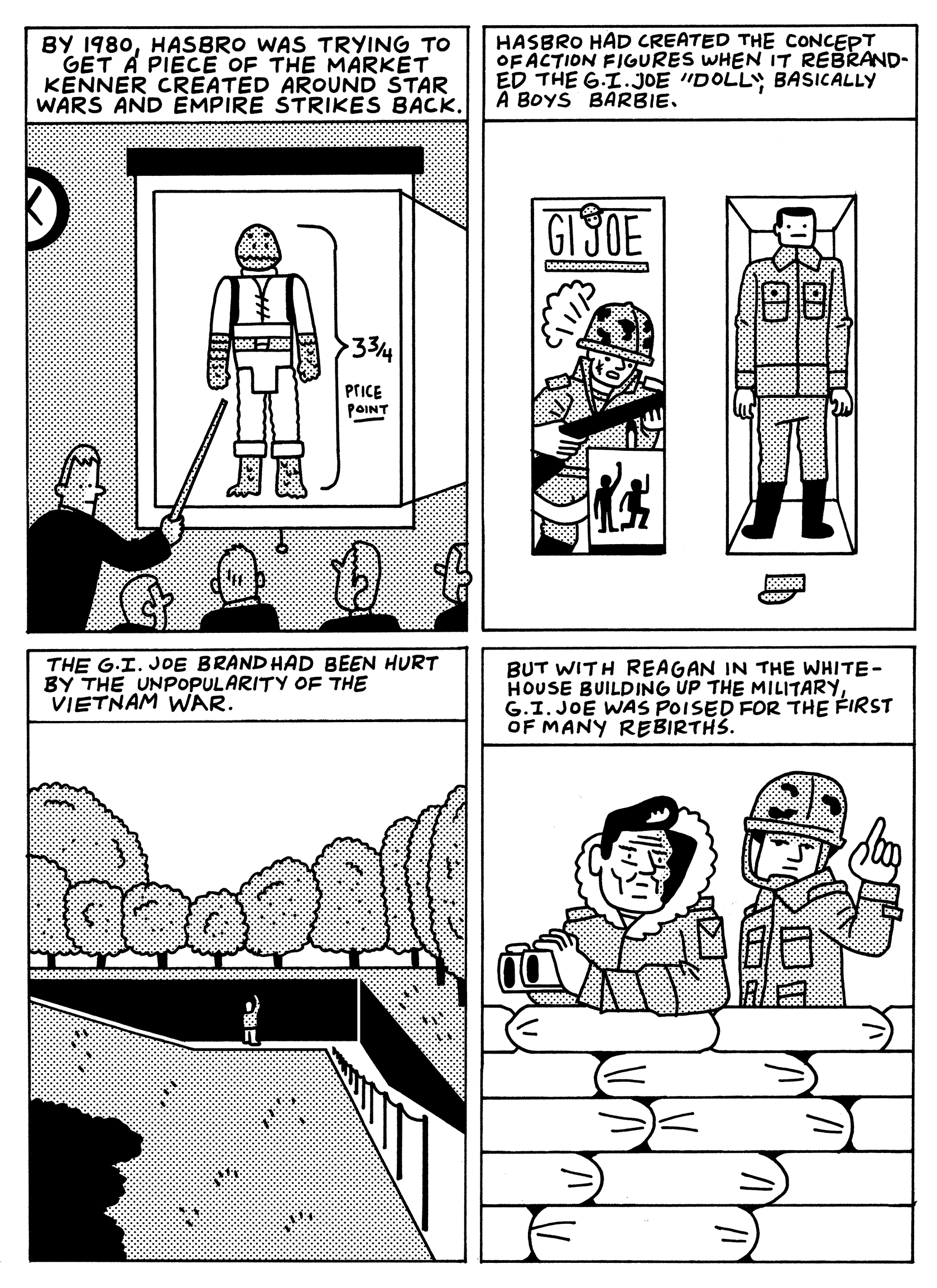

The He-Man Effect draws a basically straight line from World War I propaganda to the Star Wars sequel series that followed the property’s acquisition by Disney. Brown shows that the same use of media employed by the United States to imbed patriotic ideals into the citizenry was used by capitalists to sell toys to children. During the Ronald Reagan administration, media deregulation allowed toy companies to effectively merge advertising and children’s television, which massively benefited the commercial potential of properties like G.I. Joe and Transformers. Mattel developed Masters of the Universe with the square focus of selling as many toys as possible through the fusion of advertising and television programming.

“Writing it, I was making a lot of connections that I hadn’t previously even thought about,” Brown said.

For one of these, Brown extends the thematic backbone of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane to the abbreviated inclusion of Welles in the 1986 Transformers movie. In Citizen Kane, the protagonist has an inextricable, innocent connection to his childhood sled Rosebud. For most Americans who grew up in the '80s, their Rosebud is a Transformer, or a G.I. Joe figure, or some other product that’s part of an intricate moneymaking scheme for massive corporations.

“Nostalgia is this beautiful, wonderful feeling, but it is not the truth in any way,” Brown said.

Though the Bill Clinton administration made efforts to regulate advertising to children, it also accelerated media consolidation so that today it's six corporations that own pretty much everything. And, thanks to the boom in the '80s and '90s, today's adults are held captive to their own nostalgia. Cue the many inescapable products intended to tug on the heartstrings of adults: the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Funko POP! figures, endless sequels and reboots of the same shit, etc.

Of course, it’s a bit eerie that the release of The He-Man Effect has coincided with the blockbuster release of Barbie and an extensive New Yorker article outlining Mattel’s plans to create its own cinematic universe, including a Barney the Dinosaur movie produced by Daniel Kaluuya, billed as an "A24-type" project similar to the works of Charlie Kaufman and Spike Jonze. With these Mattel projects, it seems as though the corporate stranglehold of selling nostalgia to adults has hit a crescendo, a point almost indistinguishable from parody. But it may very well be successful.

“The Barbie movie - it is, at the end of the day, no matter what anybody says about it, an advertisement for a toy," Brown said. “But also, they know, once again, that the people they want to reach are a little bit older and more sophisticated, and they want to reach them.”

Brown, now in his 40s, shares this same nostalgic affinity for properties like Masters of the Universe and Battle Beasts, an '80s offshoot of Transformers. Over the course of his adult years, Brown has continued to collect some of these toys. But working on The He-Man Effect has contributed to a degree of a personal disillusionment with nostalgic pop culture that had already been growing for him. Brown, now a father of two children, 2 and 6 years old, wonders what this will look like for future generations.

“The bummer to me, really, is when I talk to somebody that is a parent and a friend—even other parents I meet in the neighborhood, whatever—and they’re talking about bringing their kids to Disney World multiple times per year and spending ungodly amounts of money,” he said. He doesn’t want to tell people what to do with their money, but finds this behavior a little sad, observing that parents are “not only spending so much money, but instilling in your children this intense love of Disney, where they’re going to do the same thing again to their kids in 15, 20 years, whatever.”

I told him I feel similarly when I hear about Disney trips in my social network.

“It’s almost like - if somebody was going to Vegas super-often and blowing thousands of dollars,” Brown said in reply, “you’d be like, ‘hey, maybe you have a gambling problem.’”

Yet Brown has sometimes worked inside the pop culture machinery. It’s clear from his work that he loves the WWE, and he wrote some stories for a comic book store Direct Market anthology series called WWE: Then Now Forever (2018-19). His only other Direct Market work, a pair of three-issue arcs for BOOM! Studios' Nickelodeon-licensed Rugrats series (2017-18), includes sequences in which baby protagonist Tommy Pickles imagines himself as a professional wrestler with a cheering crowd.

I remember picking up the first few of these Rugrats comics as a college student, when the Direct Market represented the vast majority of my view of comics. Some entertainment website recommended the series because of its interesting indie comics writer. I had already read and enjoyed André the Giant and found the Rugrats comics to be an interesting curiosity. The first arc featured the babies battling against technological advancements like baby monitors. The second arc, which I didn’t read at the time, sees Grandpa Lou falling down a conspiracy theory rabbit hole online, becoming convinced that lizard people rule the world.

I brought this up to Brown, and he laughed. “Did that actually come out?” he asked. I don’t think he was being incredulous.

“I didn’t love writing comics like that, really,” Brown added.

I asked if he feels pressure to create work in the Direct Market. Brown said the massive middle grade audience in the graphic novel market has created much more of a challenge in creating comics in book form for adults.

“If you look at the bestsellers list, it’s like six Dog Man titles, which is a comic for little kids that comes in book form. And it’s also Raina Telgemeier’s work and stuff like that. That’s what’s dominating book sales,” Brown said. “So if you want to be in that market, there’s a lot of pressure to do work that can be [sold] in schools.”

I’m a young millennial, and I can relate to Brown’s reluctant acceptance of the way it is, living in a society run by amoral capitalists who shape our interests and identity. I tell myself stories about how the Sam Raimi Spider-Man movies represented a time in which superhero movies were films, goddamnit, and definitely not vehicles to sell stuff like Burger King kids meals. I eBayed my POP! figures, but my Shy Guy plushie is still really cool. I still follow Amazing Spider-Man, but I listen to enough socialist podcasts that I’m not some loser, right?

It was through one of those socialist podcasts that I actually first learned about Brown’s weekly strip, Legalization Nation. Brown has appeared a few times on Left Reckoning, a spinoff of the popular progressive podcast The Majority Report with Sam Seder. The strip drops Brown less into the role of a biographer and more that of a journalist - and, once he’s on these sorts of shows, a bit of a pundit. Brown follows news related to marijuana law and sometimes conducts interviews for the strip, or looks inward for a more autobiographical spin. He monetizes the strip via Patreon, and it has a modest syndication through King Features Syndicate.

“Not to toot my own horn too much, but a lot of the stuff that I talk about in my comics isn’t necessarily part of the conversation yet, and to watch it become part of the conversation is exciting,” Brown told me. “I get a lot of funny interactions, let’s say, from regulators, legislators and stuff, [who] will read it and get mad or write to me. I get weird responses from people in the [cannabis] industry that are mad. People are mad-- not everybody, but people are mad that I’m talking about how there’s a lot of scams going on. People that are running those scams get pissed off.”

Other than the little Direct Market work he’s done, the aforementioned Putin book, Accidental Czar: The Life and Lies of Vladimir Putin, and another, Child Star (First Second, 2020), stick out.

I haven't read the Putin book and, because Brown didn’t write it, I don’t include it in my Box Brown canon. It reminds me of those few biographical books that Noah Van Sciver has drawn for other writers - works I’ve found enjoyable, but far from the real stuff. Its cover, in stark contrast to The He-Man Effect, includes laudatory quotes from Clinton era Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and George W. Bush lackey/“Never Trump” right-winger David Frum.

Child Star, rather than serving as a biographical treatment of the subject matter, is instead an original satire from Brown. I remember enjoying it when it came out, but nonetheless finding myself wishing it was nonfiction. Brown said he wanted to use fiction so that he’d have more storytelling control.

“I also was interested in doing this, like, fake documentary, fake nonfiction-style thing. I don’t know,” Brown said. “I looked back on that, and I was like, ‘why did I do that?’... I think I was getting a little bored, maybe, with the format, and wanted to just do something different.”

Brown sometimes cringes when he looks back, remarking that “it’s hard not to just look and see all the mistakes and stuff.” However, he prides himself on how much better he’s gotten at telling stories the ways he wants to tell them.

“I think the biggest change was that, I feel now when I write stuff, it’s more coming from a real place and reflecting more of my actual who-I-am,” Brown told me. “Whereas some of the older stuff I look back at, and I’m just like, ‘Oh, this is me trying to do something else or be something else or write like somebody else or whatever.’ And now, I feel like I’m better at really getting out exactly what I want to say, and it sounds more like who I am and not somebody else.”

The post Box Brown and <em>The He-Man Effect</em> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment