A word about density, perhaps? I’m always struck anew by questions of density when I dip into the British Bronze Age. It’s not perhaps the same kind of density you might expect from a particularly wordy American comic book. We Yanks quite loved our purple prose in the 1970s, but it wasn’t so big in other scenes.

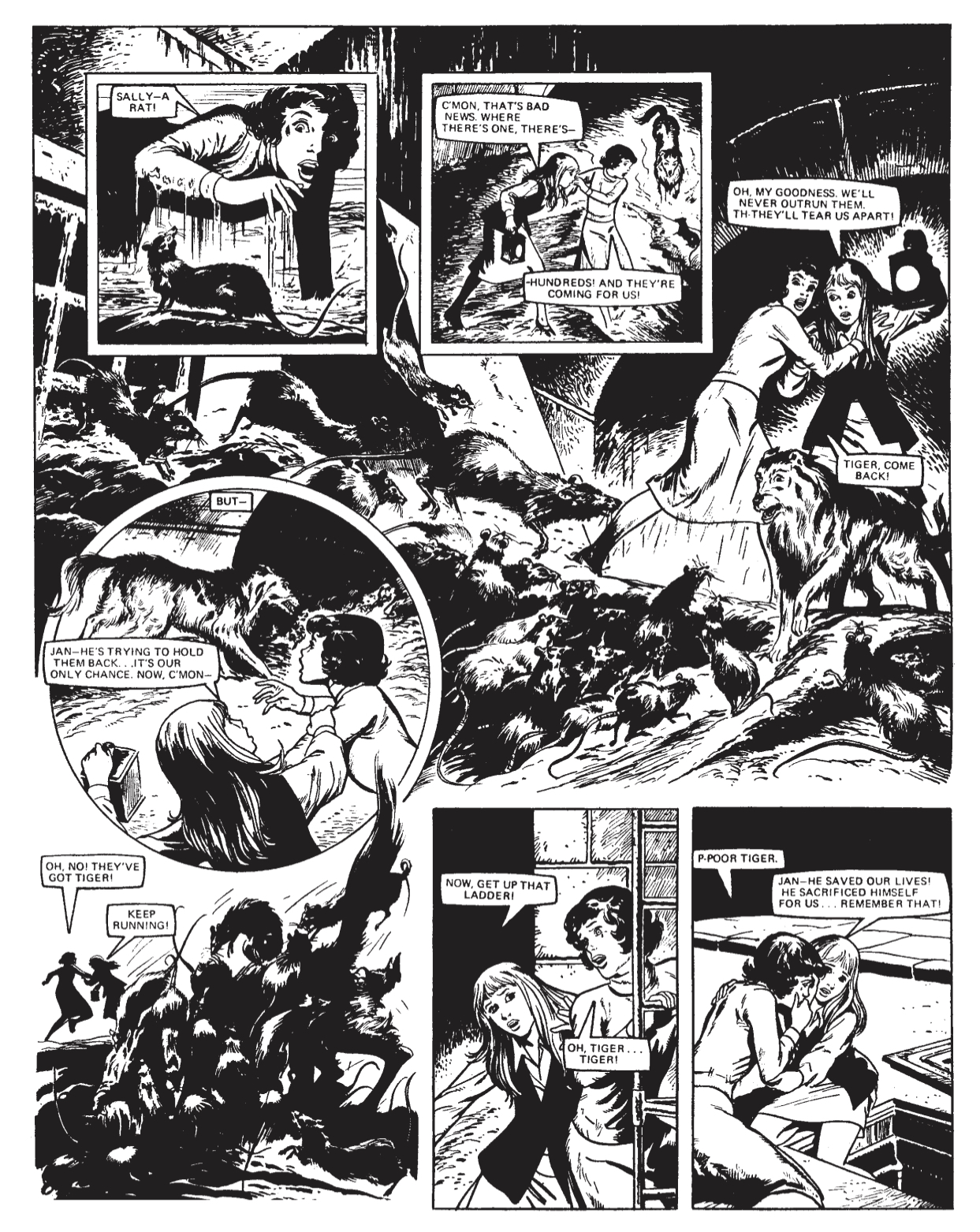

With British comics, the density seems the product of the frequency of events. More things happen per page. Pick up this forthcoming collection from Rebellion (due September 26), commemorating the venerable if short-lived girls’ comic Misty. Flip to any page - it really doesn’t matter, pick one. There’s a lot going on, isn’t there? No different from what I’d expect to find in a contemporaneous issue of 2000 AD. Misty originally ran from February 1978 to mid-January 1980; even at a weekly pace, barely the blink of an eye. Add a few subsequent Annuals and various recent revivals, and we’re still left with a magazine with an outsized influence far beyond its meagerly brief run. We’re talking about it in 2023, at least.

There’s a particularly British genre sensibility that seems to thrive at the intersection of dense and dry - do not doubt, there are dry stories in here. Dry and positively bleak in places. That sticks out of many of these tales like a sore thumb. That’s what happens when you hire Pat Mills to write a girls’ comic for you, one supposes. You get stories without much in the way of glossy euphemism. He’s the writer for the lead-off feature, the grisly “Moonchild” (1978). It’s a rather blatant lift of Carrie, adapted for local conditions. The protagonist is similarly perpetually abused, and similarly cursed with a strange and eerie power that is ultimately unleashed on her tormentors. Hapless Rosemary Black is beaten so badly by her disapproving mother that the neighbors call the cops. The sadistic girls at school smell blood in the water and set about to make sport of the most desperately unhappy person they can find.

There’s a frank and brutal honesty in these stories, all these stories, regarding the rancid disposition of human beings. Mills first pitched the idea of Misty to its publisher, IPC, and would you expect any less from a magazine drawn from his blueprint? A far cry from the American Misty. What’s that, you didn’t know there was an American Misty? In 1985, Marvel tapped Trina Robbins to make a comic book for girls to be published by their Star Comics line. The result was Meet Misty, about a teenage girl actress - a book that encouraged readers to send in fashion suggestions and regularly featured paper dolls. Aimed at a significantly younger audience, one imagines, but still one of only a handful of books on the stands in this country at the time aimed specifically at a distaff audience of girls. To find something closer to the UK Misty’s sentiment in the States, you might need to look at Warren’s black & white line. They skirted the Code the same way MAD did, by moving a few inches to the right and landing on the magazine rack instead of the comics shelf. But even then, it’s that dryness that strikes me about the British fare - a storytelling proclivity sprung from a soil in which EC Comics were a distant rumor, if that.

But my goodness, Fleetway really had a stick of dynamite in their hands here! A comic book for girls with a strong misanthropic bent - a far larger demographic than American media would credit. Flip to the cover gallery, take a look at those pieces: intense, garish, indelible. Comic book covers to start a riot. If I could have made one wish for the volume, it would have been to see more than a few throwaway references to the comics’ namesake “host,” the subject of Shirley Bellwood’s distinctive covers. Americans make cuddly mascots of our horror hosts. The Crypt-Keeper had a Saturday morning cartoon. I don’t even know if Misty speaks in puns, addresses the reader as “boils and ghouls.” Or whether she’s more in the vein, heh, of Vampirella, a host so popular they spent decades inventing the world’s goofiest vampire lore just to give her and the girls a place to hang out.

I get away from myself. Let’s look at “Moonchild” again. Art by a mainstay of the British comics world, John Armstrong. Wonderful brushwork, someone who knew how to look good in black & white on shitty paper. Never the same layout twice, which is a theme throughout the book. The nine-panel grid so beloved by American formalists doesn’t seem to carry the same weight over there. The layouts are jammed with events, stuff happening, panel after panel of framed like a tableau. Enough plot for a much longer story stuffed into a little weekly box only a handful of pages long. The skill of the artist lies in having it all make sense when the velocity of events seems to dictate a theatrical staginess. Armstrong avoids that with a canny sense of gesture. He fits in a few splash pages at surprising intervals, emphasizing points in an otherwise crowded story. What ho, early Pat Mills? Crowded? Pish and tosh.

The next serial in this collection, “Nightmare Academy” (1979) is a revelation, at least on the visual end. It's also the first story in the volume illustrated by a Spanish artist, Jaume Rumeu, one of many such artists who started working in the British market around this time, and he carries with him an illustrative tendency, small “r” romantic and highly influenced by commercial art. A very similar energy to the florid evocative carried over by the Filipino artists who impacted American comics across the 1970. “Nightmare Academy” is about an evil girls’ boarding school run by a sadistic headmistress. Is she a witch? A vampire? Something else? She’s got a whole school full of victims, at least. It’s high-key gothic: crumbling castles against a backdrop of velvet black night. Rumeu is very good at drawing sinister women menacing the tender and the innocent. It become increasingly less effective the more it becomes actually about the plot itself; like a lot of gothic stories, it goes hardest when it leans on mood to carry the day.

The third of the long serials reprinted is perhaps the strangest - “The Loving Cup” (1979), which like “Nightmare Academy” lacks a writer’s credit, lost to history. It’s about a young woman of British and Italian descent who slowly comes to realize that the Italian half of the equation is descended directly from the Borgias. These are very intense comics, even if—as here—there also seems to be a bit of intense wheel-spinning. A problem native to all extended serials on any side of the ocean, perhaps. But if the story seems repetitive in places, I suspect that might be the point - we’re watching a woman go slowly insane, haunted by a talking cup that keeps telling her to do bad things as she slowly loses her ability to resist. The artist, Brian Delaney, is new to me, but apparently a mainstay of the British scene for decades - sadly passed at the end of 2021. He draws such remarkably vivid faces: beautiful, anguished, distraught. Genuinely gifted with an eye for expression, as well as an eye for readability despite the aforementioned ubiquitous density. He’s good at utilizing sight lines as an organizing principle for page design. Toth’s pages could be remarkably dense too, but they worked.

The last of the long serials is probably the most successful, “The Sentinels” (1978) from writer Malcolm Shaw and artist Mario Capaldi. If the first three stories leaned towards the supernatural and the macabre, “The Sentinels” is a taut thriller wrapped in an alternate universe conceit. Two near-identical apartment towers stand next to each other - one of them filled with happy and prosperous families, the other an empty nightmare. Pure bad vibes. And, of course, as it turns out there’s a reason for this: the burnt out husk of a skyscraper holds a portal to another dimension, and would you believe it’s one where the Nazis turned England into a colony and its people into captive subjects? So far, so Philip K. Dick. The neglect of public housing as a vivid metaphor for the renewal of fascism, right at the dawn of the age of Thatcher. Finger on the pulse, innit.

This comic uses the density inherent in the format to pack its plot with twists and turns. More than once, while reading “The Sentinels” I was taken with the fact that this wonderfully-paced story could be adapted for the screen with little need for emendation. It just zips along. There’s certainly no shortage of stories where the Nazis take over, and they’re not all great. But this one works because it doesn’t for for any kind of elaborate cosmic pageant. The Nazis here are a direct threat to people living their lives because they’re an inherently arbitrary force who can appear at will to shoot whomever they want. It’s a world from which you’d be desperate to escape, and those are the stakes. It’s really that simple. A girl falls into that world from ours, and spends the rest of the story trying to get home before the Nazis can learn about the magic portal to a relative paradise.

The rest of the book is devoted to half a dozen short subjects, horror-tinged shockers. Half of these are drawn by Jordi Badía Romero, and at the risk of disrespecting some very talented artists, they’re probably the most impressive pieces in the book. My first instinct upon encountering his work was to remark to myself, this fellow could have been published in Creepy. Sure enough, a quick Google search reveals he was indeed. Unlikely integuments drawn across disparate traditions, meeting in the middle with lushly illustrated crosshatching and drawings of absolutely gorgeous women.

The collection ends with a pair of stories from modern revivals, both 2020. These aren’t bad, by any means. The first, “Home for Christmas,” by Lizzie Boyle and David Roach, is a ghost story for the age of smartphones and flat screen TV. Things are less grimy all around, and it reads more or less like you’d expect a horror story to read in 2020. They’ve got a regular panel grid and everything. Doesn’t seem to have a lot to do, stylistically, with what’s preceded it, nor does the follow up, “The Aegis,” by Kristyna Baczynski and Mary Safro, whose art reminds me of Colleen Coover's. Wide-open layouts, lots of room for the characters and their words to breathe. Makes sense, I suppose. But those '70s stories certainly have a verve, don’t they just?

The post Misty: 45 Years of Fear appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment