This deluxe hardback collects Alec Robbins' webcomic, published online in 2020, with a video finale released on the first day of 2021. Typically referred to as a satire, it’s not "satirical" in the way one might think of a 21st century comic featuring Betty Boop.

Because it is taking a character who in the first instance was already a satirical take on the “flapper” girls of 1920s USA, a significant part of the book could actually be described as satire inverted. Satire is often about ridicule, but the main character that ends up being ridiculed in Mr. Boop is Mr. Boop himself - or, to be more precise, its author, Alec Robbins, and what seems to be his (and, more broadly, our) dependence on fantasy worlds as relief valves for desire. In both tone and style, there’s many similarities here with surrealist comedians such as Eric André, on whose Adult Swim show Robbins has worked.

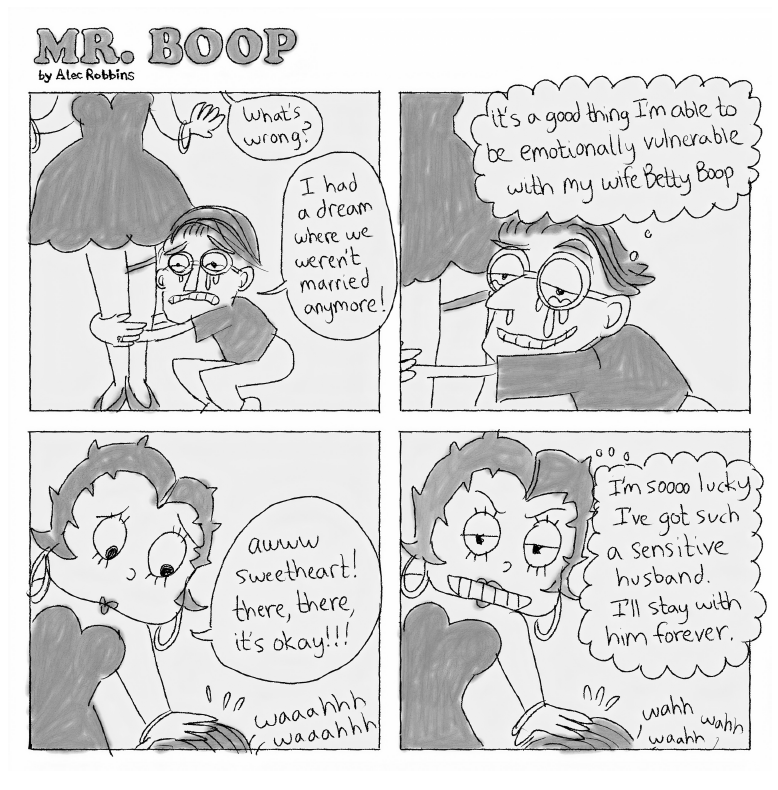

The opening pages depict Alec and Betty in domestic bliss, reminding each other how much they love each other. Alec loves Betty so much that he instructs a local attorney to shoot him if he ever files for divorce. Not that he’s really going to do this, mind. As Betty reminds him, “It would be soooo stupid to divorce me.”

A range of other recognizable characters such as Fred Flintstone and Jessica Rabbit appear, usually as the third (or more) party in Mr. and Mrs. Boop’s orgies. Peter Griffin, Bugs Bunny and Sonic the Hedgehog are three of the most common secondary players. Sonic’s maddening jealousy leads him to shoot Alec at the end of Volume I (of the four books collected here), an action that allows Robbins to branch out into dream sequences, alternative universes, and redemption arcs from Volume II onwards.

Copyright infringement and the exploitation of so-called intellectual property is a major theme, and has been much commented upon in reviews and articles about Mr. Boop. This side of things is brought into play in Volume III, when Betty's father (the “President of Cartoons,” later referred to less ambiguously as Mr. Fleischer) threatens Alec with a lawsuit unless he divorces Betty, so that Fleischer can take her back to the studio to resume her career as a perpetually single sex symbol. As Mickey Mouse tells one of the Dragon Ball Z characters, erection fully visible, “Oh, brother, that’s bad news. If her dad is anything like mine, they’re in serious trouble!!!”

Extremely light on scenery and background details, Robbins employs a scratchy, naïve visual style that prioritizes expressive character drawing and focuses attention on the story’s bizarre humor. The collection also includes guest strips that exist in the Mr. Boop universe but aren’t necessarily plot-related, and which feature other well-known intellectual properties in strange contexts. These interludes are provided by cartoonists such as Carta Monir, Sean Muscles, Emma Hunsigner, Ryan Pequin and Remy Boydell (who also provides the cover illustration), and they range from the meta self-reflective to the erotically charged.

Humor is only part of the picture, however, as a lot of the time there’s actually quite a wholesome quality to everything. It’s lewd and strange, but the general sentiment is that this couple is genuinely head over heels for each other - they talk things out, and they work on their problems together. It’s all quite sex-positive, which is maybe the biggest twist on the Betty Boop character that one could do.

This is the second book in a row I’ve reviewed for this site which collects what was originally a webcomic, and in both instances the artists have strictly adhered to repetitive page layouts - a tendency that has not escaped critical notice. Writing for Wired, Peter Rubin argues that the return of the four-panel strip (which Robbins utilizes for Mr. Boop) is due to the fact that we’ve become used to looking at squares thanks to the preferences of social media UX designers. I would propose an alternative thesis: that comics were part of a development of reading habits in the 20th century which infected digital design. The four-panel gag strip ‘works’ on the likes of Instagram because Peanuts and the like have taught us to read image/text combinations in a way that suits social media’s preference for short-form content.

Pastiche also goes way back. Underground and alternative comics have constantly borrowed, parodied and paid homage to their mainstream cartoon siblings. Sometimes this is merely for a throwaway gag, or to drop in a reference for a particular audience to pick up. But Betty Boop is a peculiar reference for a comic produced this side of the millennium. Betty hasn’t really been adopted or made cool in an ironic fashion in the same way Garfield or Mickey have. Betty still appears on plenty of merchandise, but there is always something a little kitsch about her; likely because in a lot of instances she remains a pin-up male fantasy figure - or, as her official social media pages attempt, she is written into a Girlboss narrative. ("The Original Sass Symbol.")

Betty Boop is a product of the Fleischer Studios, founded by brothers Dave and Max Fleischer. She arrived on cinema screens in the early 1930s, originally drawn as an anthropomorphic French poodle, though after a couple of episodes she became fully human. Her attributes freely taken from various cultural referents—some of the long history of Betty Boop’s copyright travails are detailed in the book’s introduction—the character was always intended as a satire on the flapper, a stereotypical Jazz Age girl, the sort of person you’d expect to come across at a party hosted by Jay Gatsby. In his 1947 book The Comics, artist Coulton Waugh described Betty as the reductio ad absurdum of the "French doll" character type. By the time Betty debuted, this type was already out of fashion, but her animated glamour proved nonetheless popular with audiences in the midst of the Great Depression. Almost as soon as the Jazz Age disappeared, those who probably hadn’t had much involvement in its more ostentatious moments became immediately nostalgic for it.

Betty was always depicted as something of a sex symbol, but she never really had any sexual agency. As Heather Hendershot described it in 1995: “from 1930 to 1934 Betty is a working woman constantly subjected to rape attempts by her employers, [and] from 1935 to 1939 Betty is placed in domestic settings and threatened only by pests such as vacuum cleaners and house flies.” One of the reasons that Betty was put into a domestic setting was because of the various religious and conservative groups placing pressure on the culture industry, most infamously via the Hays Code.

The character was something of an antecedent for the real life glamorous actresses of Hollywood’s late Golden Age such as Marilyn Monroe. (Recognizing this fact, Universal Studios has programmed shows where Monroe and Boop impersonators perform a duet.) In relation to Blonde, the much-criticized Monroe biopic from 2022, Angelica Jade Bastién asks: “Why are women so often called to represent things rather than be things in film?” This could easily apply to Betty Boop. As Monroe’s memoir My Story put it: “People had a habit of looking at me as if I were some kind of mirror instead of a person. They didn’t see me, they saw their own lewd thoughts. Then they white-masked themselves by calling me the lewd one.” The obvious difference between Betty Boop and Monroe is that the latter was an actual person, but their similarity lies in the fact that both-in different ways-were reduced onscreen to signify someone else's desires and attitudes, and then punished for it.

Monroe did many things in her life to retain and demonstrate agency. Betty can only gain agency if her author depicts her as having it. Mr. Boop is that rare occasion where Betty is depicted as having desires of her own and acting on them. Here, she is sexual but not sexualized. Mr. and Mrs. Boop’s erotic explorations are not for the benefit of the reader, but for the benefit of each other - at least, for the majority of Mr. Boop, before things get really strange. The titular Mr. Boop isn’t just anyone, he is the strip's author (or, a cartoon avatar of him). Citing legal issues, Alec tries to undo the mess he’s made trying to persuade us of the veracity of his dream world. At the start of Volume IV, he tells us that he is now depicting his real life (titled "Mr. Mr. Boop").

At the supermarket, he runs into a female fan called Elizabeth whom he ends up dating and sometimes accidentally calls “Betty.” At one point, Elizabeth asks Alec, “Why are you changing what I say in the comic?” This is the first hint that once again Alec the author/character might not be completely honest with us. Elizabeth's hair soon changes into more of a bob, then she starts wearing a red tube dress, and soon enough she’s called Betty Boop and married to Alec. He’s trying once again to get us to believe that his fantasy is real. Bugs Bunny guesses that something is up, takes Alec aside for a small beating, but eventually it is Elizabeth/Betty who gets Alec to see that he’s dug himself a hole he can’t get out of without just putting the pen down.

The book ends in an arch manner, with the guest characters returning to their original forms and contexts before Alec himself dissolves. In some ways, it’s a copout of an ending, allowing meta commentary to substitute for the final act of a narrative arc. On the other hand, it’s about the only way the book could have concluded without the plot circling around on itself. It seems that unless he can channel his desires in some way, Alec is unable to picture himself as existing.

We’re thus made aware that this comic is mostly about Alec’s obsessive depiction of his own desires, which means that the ‘Betty Boop as actually liberated’ theme thus doesn’t survive the text; this feels like a shame for Betty. Mr. Boop ends up reflecting on the fact that Betty Boop’s only hopes of autonomy lie within the hands of whomever is writing and drawing her, and that at the end of the day her and cartoons like her don’t have any genuine agency, and are always—to different extents—vehicles for the desires and dreams of their authors. Alec can disappear from the make-believe world he’s constructed, but the characters are stuck there, waiting for another pair of hands to come and bring them to partial life. What they do says more about the context in which they’re brought about than it does about them as characters.

This isn’t about the return of the authority of the author, it’s about us each being authors, expecting to find something in fiction which we can relate to ourselves. Inspired by real-life starlets, Betty Boop may ask: why are you looking at me as if I were some kind of mirror? One’s interior world can be a daunting place, and sometimes the best way to deal with it is to admit that you really love your wife, Betty Boop. But Betty isn’t real, so the question to ask is: what and whose fantasy is she serving?

Traditionally, Betty Boop has been the main character of her films, yet she has been subject to the wills of the male characters in her world. Here, she isn’t the main character exactly, and her fictitiousness is highlighted, but for the most part she has an equal amount of involvement and emotional investment in what happens as anyone else in the story. She makes decisions, rallies against her own objectification, and has feelings that motivate her. Betty always talked and sang, but in Mr. Boop she finally has a voice, albeit one that is filtered through the continuum of male desire that imagined her in the first place.

The post Mr. Boop appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment