By the lights of industry myth-making, it is Tom Scioli’s deep affinity for the work of Jack Kirby that makes him a fit to produce I Am Stan: A Graphic Biography of the Legendary Stan Lee. After all, who better than Scioli—an artist who has spent his career in vocal emulation of Kirby—to expound on the life of the writer with whom his hero worked so closely, to such popular and lasting results? Decades of Marvel marketing pegged Lee & Kirby as inseparable and affable colleagues who ushered the era of superheroes into the zeitgeist. The Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, the Avengers - and the list goes on. As the mouthpiece and public face of the company, Stan Lee was not just the author of Marvel’s stories, but also the author of the Marvel Story, who positioned himself as the visionary in his various partnerships, leaving artists precious little room to refute those claims, at least within official channels.

But the workings of Lee’s collaborations received scrutiny from the outset. Initially, it emanated from an obsessive fanbase eager to parse the creative process of a novel medium. It would grow to become an ongoing case study in creators’ rights to benefit from their increasingly lucrative creations. Of course, how that shook out within the context of a collaboration was moot, given the strict corporate control exerted over the fruits of their labor. Although Lee the Marvel mascot is still viewed affectionately in the annals of pop culture, that affection is not dissimilar from the affection reserved for the likes of Mickey Mouse or Ronald McDonald: a fond association with a much-loved brand. The intervening years have seen Stan the Man’s jocular reputation tarnished. In the pages of Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story and Abraham Josephine Riesman’s True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, to cite two examples, investigation into Lee’s claim to the many characters for which he was initially credited has revealed, unsurprisingly, a more complex picture, more in keeping with the collaborative nature of making comics. These reports confirmed for a mainstream audience what was long known to readers in the niche circles of fandom.

Scioli’s relationship with Kirby situates him somewhere between super-fan and scholar. He previously wrote and drew Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics, a 2020 graphic biography similar in format to the one discussed here. As such, Scioli brings an obvious set of biases to the subject of Lee’s career. The controversies that marked Lee’s and Kirby’s relationship color I Am Stan, but don’t dominate the narrative. Scioli largely eschews the opportunity for score-settling to paint a more complex picture of Lee’s life and legacy in and out of comics. If Scioli’s fondness for Kirby and his work complicates his perspective in producing a biography about Lee, the man who arguably diluted his hero’s legacy to bolster his own, it positions him well amidst the complicated state of discourse on the subject of Lee’s life.

In Scioli’s telling, Stan Lee was not driven toward a destination as much as a desire to keep up with traffic until he could find an off-ramp to something better. The connections he forged in collaboration with colleagues like Kirby, Steve Ditko, and John Buscema were soured by Lee’s personal ambition, his inability to share credit, and his lack of loyalty to peers.

But I Am Stan is not purely a litany of sins, nor is it solely an apologia. What Scioli delivers is a character study rife with Freudian pathos and professional frustration, more in keeping with something the Coen brothers might put on the screen than the surface-level storytelling associated with graphic biography, a genre that too often resorts to Wikipedia regurgitation. It begins with Lee’s—née Stanley Martin Lieber’s—birth to working class Romanian-Jewish immigrants, struggling to make ends meet in New York City in the years leading up to the Great Depression. Scioli depicts Lee as a bright, socially awkward youth beset by his mother’s expectations.

Early in his career, Lee's connection to his cousin, Timely Comics owner Martin Goodman, nets him a job as an assistant gofer, his entrée into an unfamiliar industry that is already running at full bore upon his arrival. Lee fetches coffee and sharpens pencils for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, but is soon angling for opportunities to try his hand at storytelling. It is not long before Lee is writing alongside a number of artists, while taking on managerial and editorial responsibilities. His ambitions are on full display here, but he is still just a middle manager eating shit from above and below.

The artists want more work, more money, and less editorial oversight. The bosses want ideas that sell, but are reluctant to risk trying anything that hasn’t been proven out. Lee tries to manifest the prodigious bustling qualities that he believes served him so well in his youth, but are seen with ambivalence by just about everyone. In a particularly humiliating flourish that underscores the class dynamics at play, Scioli depicts Lee making the trek down a long hallway to conduct meetings with Goodman, who is lying on the fainting couch in his spacious office, groggy from his daily afternoon nap. Lee brings Goodman ideas, but his naïveté to business concerns do little to ingratiate him. Here Scioli is doing his best Mad Men routine, reveling in mid-century angles, palettes and fashion.

As a manager, though, Lee is more Pete Campbell than Don Draper: charmless, tactless, and most interested in the concerns (and perks) of middle management. The best he can muster is to deliver on his boss’s schemes to keep the publications in step with market trends and occasionally offer up colleagues and subordinates when they run afoul of his employer’s best interests. At turns, we see Lee colluding with DC’s Carmine Infantino to “keep each other in the loop about what we pay our freelancers,” wiring the office with closed circuit television to monitor artist productivity, and turning his back on Neal Adams’ efforts to organize artists and writers for better working conditions. “Well, if you want to start a union, you’re going to have to do it without me,” Stan says. We also get Lee “playfully” lashing the artists under his supervision with a bullwhip, crossing out an artist’s work before returning it, and the strong implication that it was him who ratted out Simon & Kirby for moonlighting, leading to their termination.

Scioli doesn’t expressly editorialize, though his selection of anecdotes is often pretty damning. He doesn’t shy away from depicting Lee in a humane light, either, but mostly tags these bits as Lee’s pragmatism - efforts made in consideration of business needs, such as when he is admonished by Goodman for maintaining an unpublished surplus of art that he solicited solely to keep the artists in work... so they wouldn’t jump ship to the competition. Scioli also delivers on the more lighthearted moments that might be expected from a Stan Lee biography. We see Lee puzzling out the mechanics of the famous Marvel Method, coining catchphrases, posing nude for a Marvel promotion, and finding his footing in front of the camera as a perennial cameo actor. In a very amusing bit, Lee is depicted farming out some of the creative work to his brother Larry Lieber and getting really annoyed when Larry doesn’t use alliteration to name the characters: “‘Tony Stark?’ Not ‘Stephen Stark’?”

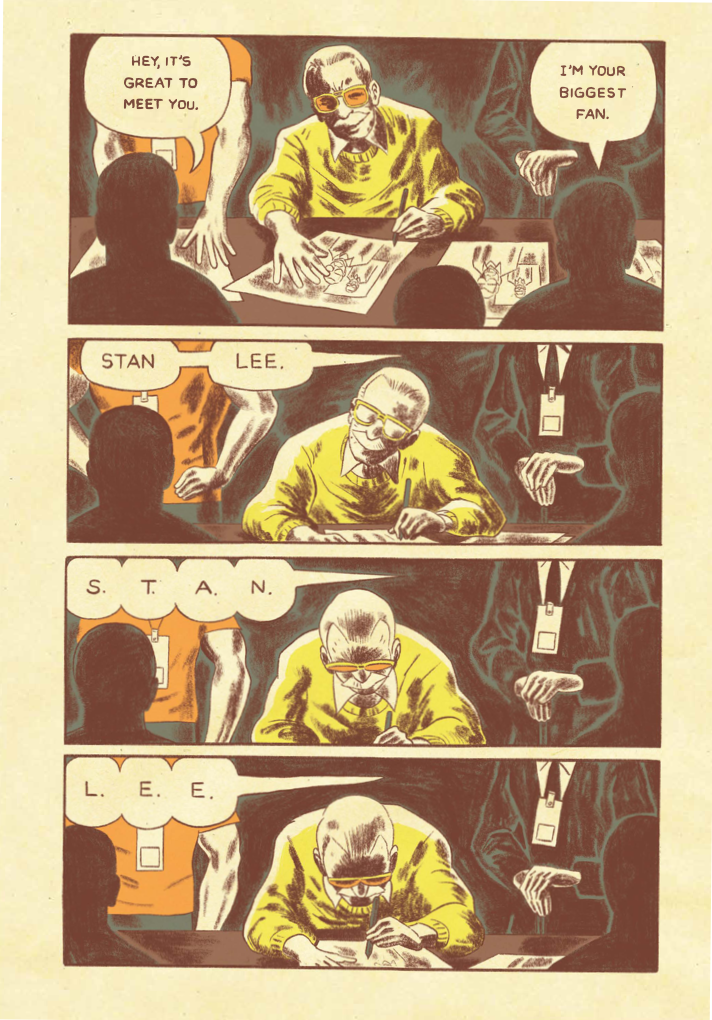

The depictions of Lee's collaborations are almost magical in their succinctness. In a repeated motif, we see Lee and Kirby in partial silhouette, struck by mutual inspiration. The balloons that describe the foundational qualities that will define their creations for decades to come appear without attribution tails, mingled among Kirby’s cigar smoke. Try to do that as pithily in prose. But Scioli shows his work in the endnotes. He draws from the works of Riesman and Howe, as well as ostensibly friendlier works, such as A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee, Danny Fingeroth’s 2019 offering. Bibliographies aside, it’s the extensive index that gives a fuller picture of the book’s construction and how Scioli manages to tell his story so concisely - there are few anecdotes that exceed one page of storytelling.

Scioli is no stranger to sprawling narratives, but constraints are not unfamiliar to him. Consider the scope of Transformers vs. G.I. Joe (2014-16), his strongest work to date. It’s an epic packed with asides and tangents, many of which don’t even properly conclude so much as they drift out of focus. It’s fifteen issues of only interesting and cool parts that feel like they add up to what would be 30 or 40 issues of any other title. Then, consider the "Super Powers" stories that ran as a back-up in Cave Carson Has a Cybernetic Eye. In just a few pages he produced the most interesting thing published under DC’s short-lived Young Animal label. In comics, stories succeed or fail on the strength of pacing and compression. There are few artists as attuned to the economics of the page as Scioli. Through impeccable timing, Scioli can express in just one or two panels what other artists do in ten. It results in stories that feel like an accrual of defining moments. Pynchon and Bolaño are who I think of when I read something that finds Scioli is in his groove.

Lee’s signature look does not appear until midway through the book, but each step towards it feels like a revelation. He dons a toupee, and we soon see him sparring with a Wertham acolyte in defense of the medium and receiving no less than a fawning Federico Fellini at the Marvel offices. In short order, Scioli shows Lee hitting his stride in a slew of speaking engagements that seem to mark his ascendancy. He addresses raucous college students, appears on a talk show to weigh in on racism, and presides over “A Marvel-ous Evening with Stan Lee” at Carnegie Hall. In depicting these speeches, Scioli allows the word balloons that comprise Lee’s monologues to dominate the page, emphasizing that his congenial showmanship was rooted in language. In Scioli’s estimation, Lee was only fully himself within the trappings of his public persona, and that made him unknowable. That’s why I Am Stan works best when taken as a character study.

Scioli's figure work is sparse, and he offers readers precious little in the way of backgrounds. In this way, Scioli seems to vacillate between the literal and the metaphorical. He tries his best to hold Lee in focus through a consistent visual shorthand and a broad base of research, but Lee remains elusive. Characters stand against minimal backdrops or nothing at all. When Lee is talking, the people gathered around him are often depicted as nothing more than human forms in silhouette.

All of this evokes a paucity of purpose and a thinness of character, especially when taken in conjunction with the richly rendered backgrounds of Scioli's Kirby biography, an element that anchored Kirby’s story in a time and place.

I Am Stan opens with Stan Lee’s 1971 appearance on the game show To Tell the Truth. Contestants quizzed three guests, Lee and two imposters, in an effort to suss out the genuine article. In response to one contestant’s then-outdated understanding of comics as a medium, in which art and story are the work of one person, Lee withers. “Um… they got too busy to write their own stories,” he says. Lee seemingly spent his life trying to justify his place in the world. It remains unclear whether he was trying to make a case to the people around him or to himself.

The post I Am Stan: A Graphic Biography of the Legendary Stan Lee appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment