In the same month that famed cartoonist Milton Caniff signed the deal to draw Terry and the Pirates, he received the following note from an editor about his work:

“I think you’re losing something in your drawing — a quality you had when you first went to New York. Your sketches are getting to be cut and dried — and too cartoony. I wonder if you remember a negative-souled little artist who used to work in Kline-Roberts office in Columbus. I haven’t thought of him in years, but somehow your sketches remind me of his art which fairly breathed ‘small-town-commercial-artist.’”1

The criticism was levied by Lonore Kent, who’d given Caniff a freelance assignment and wasn’t pleased with his latest work.

“I suppose by now you’re saying ‘Ouch!’ But I mean that you should. Maybe your stuff is what the newspapers favor, but I still don’t think it is a good idea to play down to your audience.”

Kent warned Caniff to stay away from the “comic-strip style” and wondered when he was going pursue magazine illustration.

Kent’s method of criticizing Caniff was not the cold bullying of a strict boss, but the firm goading of someone who knew that the person she was speaking to could do better. Their style of communication had developed over good times and bad for both artist and editor.

When Kent first contacted Caniff about freelance work in 1931, she had just moved to Washington, D.C. to become editor of Save the Surface Magazine for the National Paint, Oil and Varnish Association, Inc.2

Kent started writing professionally at the age of 13 and later relocated from her hometown of Pittsburgh to California, with the dream of writing for the movies.

“I went through the looking glass the wrong way,” Kent told the Northern Virginia Sun in 1962. “Instead of training to go to Hollywood, I got my training there.”3

While Kent was happy to leave Hollywood behind, she did value the practical experience it gave her.

“There I learned to write simply, how to sense audience reaction and the best way to present an idea,” she said, in 1962. “I also learned to have no hesitancy about tackling a problem.”

The problem Kent faced in May 1931 was she needed an illustrator.

Save the Surface was not just a magazine, it was a whole marketing campaign designed by the National Paint, Oil and Varnish Association — soon to rebrand as the National Paint, Varnish and Lacquer Association, Inc. — to promote various surface coverings for industrial, commercial, and residential use.

Consumers of the 1920s and 1930s were familiar with the slogan of the paint and varnish industry, “Save the surface and you save all.”

America was two years into the Great Depression and few people had money to redecorate their homes. Kent’s job was to write, edit, and publish stories that inspired her audience to see paint — and color, in particular — as a way to transform their lives.

Plus, as the slogan said — “Save the surface and you save all” – paint was a good way to protect your investment. Maybe you couldn’t afford new furniture, but how much does a can of paint cost? You could make a big impact at a relatively small expense.

In May 1931, Milton Caniff was working full-time as a staff artist at the Columbus Dispatch in Ohio. Like Kent, he was 24 and ambitious.

He’d started drawing when he was very young. After working on his high school newspaper and yearbook, he attended Ohio State University in Columbus.

College proved to be a blossoming period for the young artist from Dayton. Not only did he provide illustrations for Makio and the Sundial, Ohio State’s yearbook and humor magazine, respectively, he also joined the Sigma Chi fraternity and performed in campus theatrical productions as a member of the Scarlet Mask musical comedy troupe. He even combined his two interests by providing artwork for Scarlet Mask’s programs and flyers.

To supplement his income, Caniff worked part-time at the Dispatch under the tutelage of Billy Ireland. It was the iconic Ohio cartoonist who encouraged a young Caniff to abandon his theatrical aspirations and focus instead on making cartooning his life’s work.

“Stick to your inkpots, kid! Actors don’t eat regularly!” Ireland said, in a moment Caniff immortalized in a 1978 drawing.

The young artist took that advice to heart. After graduating from OSU in June 1930, Caniff joined the Dispatch full-time. Two months later, he married his high school sweetheart, Esther “Bunny” Parsons.

At a salary of $40 a week, Caniff first worked in the promotions department, drawing advertisements encouraging readers to purchase a subscription, as well as other illustrations for the Dispatch as needed. But, as the local economy began to feel the pinch of the Great Depression, the paper closed its promotions department and moved him to the art desk full-time, with a $5 bump in pay.4

While work at the Dispatch kept Caniff’s pen and brush busy, he dreamed of making it big beyond Columbus, either as the creator of a comic strip or as an illustrator. With Bunny’s help, Caniff wrote letters to editors, cartoonists, and admen in Cleveland, Chicago, and New York, asking for advice and pitching ideas for comic strips and illustration work. But the economic downturn had hit the big city papers and advertising agencies hard. There were no jobs to be had.

All through 1930 and the first half of 1931, Caniff was making connections and finding freelance work to supplement his income. One of those connections was Lonore Kent.

“I must hasten to say that your letter interested me greatly, not only for its immediate possibilities but for the future it might hold,” Caniff wrote, in May 1931.

In the letter, he compliments Kent on the copies of the magazines she’d sent him, praising their “makeup and paper stock,” which made for a good presentation.5

“Naturally I should be happy to take on as many of the drawings as you could toss my way,” he said. “The financial angle is not to be laughed off and besides I like to have my stuff spread around the country as much as possible.”

The 24-year old artist ended the letter in a somewhat familiar and even “flirty” tone.

“I hope we can promote something to our mutual advantage out of this – I like to do this sort of thing because it must not be long before I hit New York with the million other starving, but ambitious artists and the contact will do no harm. Then too I enjoy working with you – and that is some little something in itself isn’t it?”

The letter said a lot about who Caniff was in the middle of 1931. While it was confident and professional, it also hinted at the frustration and underlying desperation he felt wanting to make it to the big leagues.

Below his signature, Caniff added a postscript that was surprisingly revealing:

While I am on the subject of my not so secret ambitions I might add that what I like to do is to make a connection with either an advertising agency or magazine using the art training that I have in conjunction with the knowledge, advertising layout, copy and so on that I have been gathering over a period of time. These combined with whatever sales ability I have seem to me to be a greater background than most advertising men bring to their profession. Somehow it seems hard for agency people to recognize the fact that a newspaper artist should even think of these things since a great part of his work deals with doing pseudo comic cartoons and illustrations.

The whole point in my spilling all this to you is that if such a situation should reveal itself to you I would appreciate knowing about it.

In just a few years, Milton Caniff would revolutionize the comic strip art form and become a household name to millions of loyal readers due to his groundbreaking work on Terry and the Pirates. Then, in 1947, he had enough confidence in his abilities to walk away from all of that and start a brand new comic strip, Steve Canyon, in exchange for a bigger paycheck, ownership, and full creative control.

And yet, here was the same artist 16 years earlier, a young man near the beginning of his career, trying hard to land a job helping to sell paint to the masses.

Kent had plenty of work to give Caniff. Not only were there stories for Save the Surface Magazine that needed illustrating, she also was producing content for newspapers and magazines across the country.

Caniff used skills he’d picked up at the Dispatch to lay out a full page of Save the Surface stories and artwork that newspaper editors could use free of charge. Editors were encouraged to use the features if they ran short of copy. Each page or “mat” included a disclaimer at the top:

To the Editor:

These illustrated stories are offered [to] you without charge for exclusive publication in your city. The information submitted is technically correct and no specific product, dealer or manufacturer is alluded to. These articles are particularly suitable for your woman’s page or your home building section. If you have any suggestions regarding future stories, won’t you please let us hear from you?

Cordially,

Publicity Department6

These days, what Kent and her team of freelance writers and artists were producing would be called “sponsored content.” It wasn’t quite advertising, but it wasn’t really journalism either.

The information in the stories might be 100% accurate, but it was being presented in a way to motivate the readers to think about redesigning their homes. Hopefully, they would do so by either purchasing paint from one of the retailers or hiring one of the professional decorators advertised elsewhere in the same newspaper.

The stories featured headlines like “A Frame for a Picture," “Are You Proud of Your House When You Come Up the Street?,” “Are You the Envious or the Envied One?,” “Artistic Radiators,” and “Colorful Cures for the Blues.”

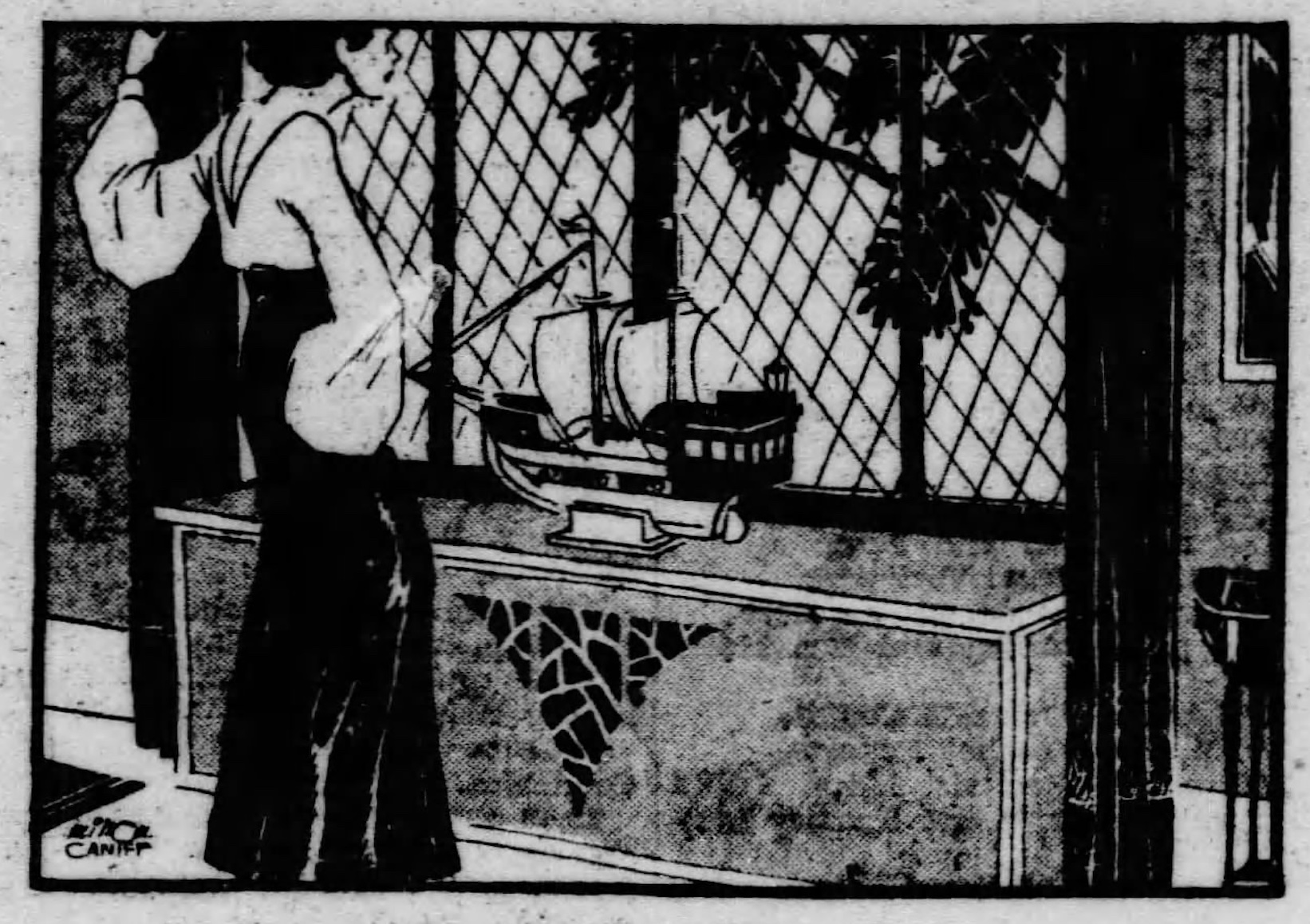

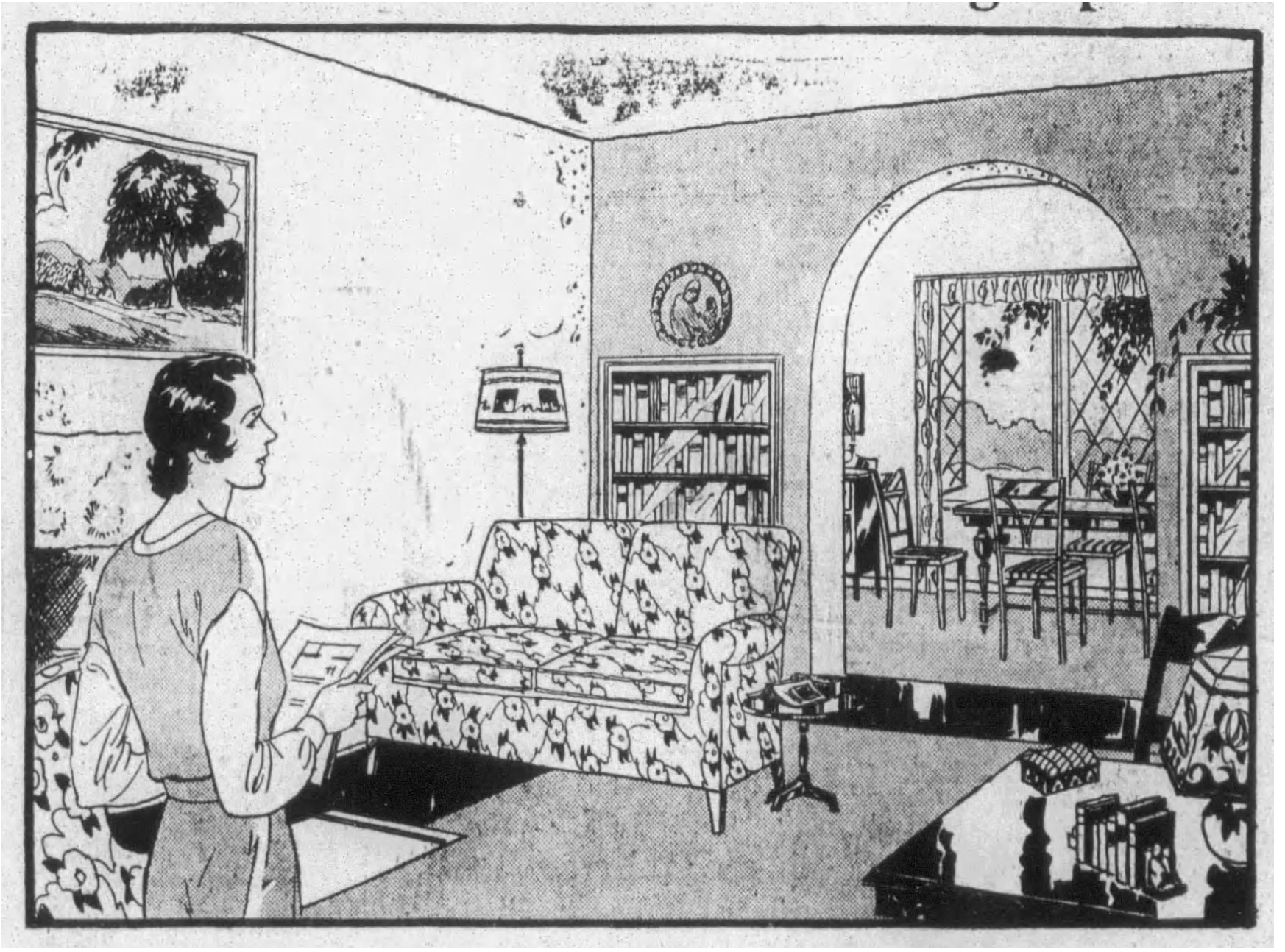

To illustrate them, Caniff drew beautifully attired people showing off a newly redesigned living room or staring forlornly and wondering, “Maybe a good coat of paint would fix that old desk.”

In one story, entitled “A Century of Color Progress,” a housewife, dressed in an apron with a paintbrush at her hip, envisions the futuristic color schemes of the Chicago World’s Fair and imagines how they could enliven her drab kitchen.

It was a testament to Kent’s creativity that she was able to keep finding new, entertaining ways to sell paint. Caniff illustrated a story by Helen B. Ames entitled “Paint Attracts Patronage: Tints That Soothe and Please the Eye are Excellent Business Getters” for Master Barber Magazine and Beauty Culturist.7

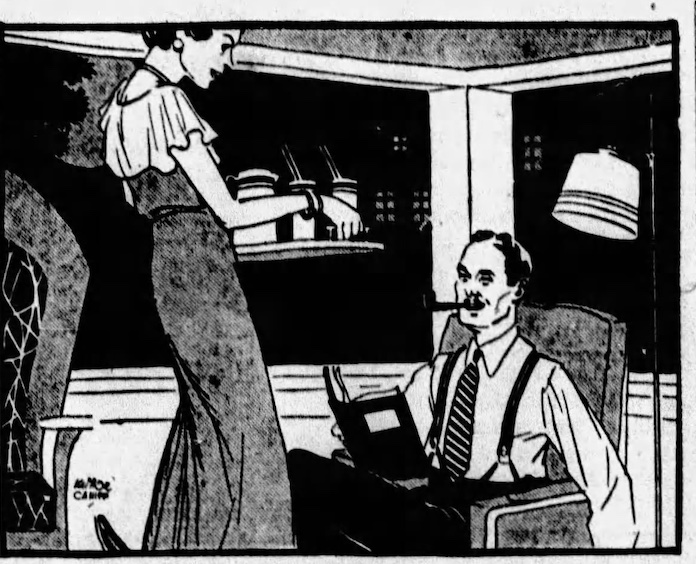

The workflow was fairly straightforward. Kent would send Caniff copies of stories or the glimmer of an idea she had for a feature she planned to write. He would send her pencil roughs and layouts to review.

“These sketches will give you an idea about the stuff – just shoot me a wire or a special and I’ll finish up the drawings tonight,” Caniff wrote, in one letter. “Advise me too if the lettering is the style you want.”8

Kent would either approve Caniff’s concept or send notes with a request for changes, communicating by letter or even telegram if necessary. The artist then did the final drawing in ink and mailed it to Kent.

The letters between the editor and artist were businesslike and chatty, although sometimes Caniff would become overly dramatic if he made a mistake or was late on an assignment.

“I shouldn’t blame you if you were angry with me for seven years straight,” he wrote in one letter. “In fact there are so many things to be apologetic for that I shan’t even start. Suffice to say that I am most grateful to you for being patient with me.”9

In another, Caniff apologized profusely for sending a package of artwork to a Dayton address instead of Kent’s office in Washington, D.C. He only discovered the error when the package was returned to him unopened.

The mention of hard times at the Dispatch was just an omen of what was to come. While maintaining his job at the newspaper, Caniff began working part-time in November with Noel Sickles on a commercial art enterprise.

Sickles was a gifted artist from Chillicothe, Ohio. He and Caniff had first met in 1928 when Sickles, who was still in high school at the time, wandered into the Dispatch office and asked if Caniff would look at his artwork. When Sickles enrolled in Ohio State that fall, Caniff convinced him to pledge Sigma Chi. The pair formed a lifelong friendship.11

It’s difficult to underestimate the impact that “Bud” Sickles had on Caniff’s work. In later years, the two would share a studio in New York City. As Caniff developed Terry and the Pirates, Sickles filled in for artist John Terry on the Scorchy Smith comic strip for the Associated Press. When Terry died, Sickles took over the strip and began to apply a chiaroscuro style to his artwork that Caniff incorporated into Terry and the Pirates with great success.

But that is a story for another day. Suffice it to say, the partnership with Sickles at the end of 1931 came at a fortuitous moment for Caniff, because the Dispatch laid him off in mid January 1932.

Scrambling for work, Caniff at first took a job as an advance man for the touring company of a local theater group with which he’d been involved. They were traveling around Ohio by car and performing shows in small towns. Eventually, when the troupe ran out of money, Caniff returned to Columbus and joined Sickles full-time.12

The pair started an overnight advertising service. Caniff would drive to Cincinnati, Dayton, and Akron during the day to meet with advertising executives and sell them pamphlets, booklets, ads, and covers, which he’d promise to deliver within 24 hours. He’d then drive back to Columbus, where he and Sickles would produce the desired products for Caniff to deliver the next morning. It was back-breaking work, but they were soon splitting up to $200 a week.13

“Lonore, you angel — Just on one of the bluest Mondays you can imagine I get your swell message,” he wrote. “The check was most welcome – as you can imagine.”14

Then everything changed. Wilson Hicks, an associate editor with the Associated Press, sent Caniff a telegram asking if he was available to take a job in the Feature Art Department of AP’s New York City office.15

On May 31, Caniff penned a letter to Kent sharing the good news. “I have landed the A.P. job in New York. I am leaving Columbus today — arrive there tomorrow morning. That means that I will be delayed just a bit in getting the sketches back to you — but it will only take me a day or so to get straightened around. … I have to hit the trail now. It’s the chance I have been waiting for.”16

In the next letter Kent received, Caniff itemized the sketches he was sending her and shared his new Tudor City address in lower Manhattan. He also congratulated her on the publication of the first issue of Tint & Tone, a magazine published by the Save the Surface Campaign featuring sketches from “the facile pen of Milton Caniff.”17

“I shall have the sketches back from you in a day or so I presume,” he joked. “The moment they arrive I shall send them back finished. … And no monkey business this time. I assure you.”

But the artist also expressed frustration with his new job.

“I have had one sweet time getting into the swing of the AP’s way of doing things here,” he wrote. “Not that the sort of thing they do is foreign, but syndicate methods are much different than those of a daily paper. For one thing they have you do the stuff over several times … not because they don’t like it as much as that. They just like to try different methods to find which they like best.”18

However, the honeymoon period between the artist and editor over Caniff landing his dream job was short-lived.

“Where in the Sam Hill are the other mat sketches?” Kent wrote, in early May. “I will have the finished ones of the other four in my hands tomorrow. I must get the mat on the press immediately. You have only had since early in March to do this anyhow. If you haven’t already mailed the rough so that I’ll receive them tomorrow morning (Saturday) at the office, mail them to me at my home … so that I’ll receive them Sunday, and can have them back to you Monday morning. If I don’t hear from you by Sunday I am going to start sending you ‘collect’ wires again, whether you are broke or not — It’s good for you.”19

Kent’s letter also contained a $120 invoice for the artwork Caniff drew for six newspaper mats. So, while the $60 a week he was bringing home from the AP20 was more than what he’d earned at the Dispatch, the equivalent of two-weeks’ pay from his Save the Surface work likely made it easier for him to endure his editor’s occasional wrath.

Caniff’s connection with Kent proved valuable in other ways too. Before he took the AP gig, she’d given him a contact at the Ladies' Home Journal, which was looking for an illustrator at the time.

Kent reached out on Caniff’s behalf to P.S. Redford, director of merchandising at the Thomsen-Ellis Company, a Baltimore-based printing house that specialized in creating direct mail marketing campaigns.

“Miss Kent has told us something about the work you have been doing and has shown us some of the drawings that you executed for her,” Redford wrote Caniff in January 1932. “We appreciate the opportunity of considering the possibility of passing along some of our art work to you on a free lance basis, or perhaps later making a permanent association with you.21

Although a full-time job at Thomsen-Ellis failed to materialize, Redford did solicit sketches from the artist for a cocktail book the company was putting together.

“I have been mulling over the cocktail book for so long because I want to catch the exact flavor of the thing if I can,” Caniff wrote. “Over the weekend I’ll put the stuff on the dummy and see what happens. It will be ready when Redford calls on Monday.”22

As tantalizing as a cocktail book illustrated by Caniff might have been, there was nothing in Caniff’s letters to Kent that suggested he’d gotten the assignment, just that he was waiting to hear back.

In one of his letters from this period, Caniff mentioned that the New Yorker had rejected some of the “bits” he submitted for their consideration.

“They seem tough as hell to crash but after what they said about this initial effort, it does not seem entirely impossible,” he wrote. “Maybe the stuff will really click one of these days.”23

The New Yorker rejection included an encouraging note from a fellow cartoonist from Ohio.

Dear Caniff:

I’m sorry the art conference didn’t take any of these ideas – personally I was for several of them, but I have no voice in the selection. It’s hard to break in up here but I’d like to see you keep trying. I hope you’re selling elsewhere and that everything is okay with you.

Jim Thurber24

Caniff ended his letter to Kent acknowledging that he’d sold a couple of gags under another name to the New York American newspaper.

At the same time Caniff was bemoaning his bad luck, work had begun to pick up for Kent. She had started providing copy and promotional materials for Save the Surface’s foray into a new medium, a 15-minute radio show called Color Magic. That meant she was able to hire Caniff to illustrate promotional materials for the show.

One of the more oddball assignments was designing cardboard cutouts of some of the characters Caniff had drawn for Save the Surface Magazine. Standing about 28 inches in height, the figures were used as part of a convention display for the National Paint, Varnish and Lacquer Association. The idea was to illustrate how the Save the Surface Campaign was reaching a nationwide audience through its magazines, radio show, and newspaper inserts.

Kent liked them so much that for the next year’s convention she planned to frame them individually and hang them as if in an art gallery.

“I have always been of the opinion that your radio listener was much too dizzy, but due to the fact that you were so swell and did them in such a rush for me I didn’t cast any aspersions on her,” Kent wrote. “Will you do me a rough sketch of another composite radio listener. You might make her a bit older this time. I’m toying with the idea of having the radio listener beside a radio twirling the dials on account of its sorta hard to represent a radio listener without a radio.”25

In mid September 1932, Caniff had some good news of a sort to share with Kent.

“On Monday of this week one of the comic strip artists at the office failed to show up,” he wrote. “Inquiry found him ill with a cold or something. He was away [sic] behind with his stuff so I was given the job of ghosting it and bringing it in under the wire.”

The “ill artist” was Alfred G. Caplin, later known as Al Capp, the creator of the Li’l Abner comic strip. Since March, he’d been drawing a daily, single-panel comic for the AP called Mister Gilfeather, which cartoonist Dick Dorgan had launched in 1930 as Colonel Gilfeather.

Capp struggled with the strip, which he hated. But even after he had shifted the focus away from the original lead character, it was a doomed enterprise. Caniff chose to tell Kent that Capp had fallen ill rather than report the truth. Fed up, Capp quit AP and returned to his hometown of Boston to lick his wounds.26

“There were twelve drawings due yesterday and with the writing of the continuity and making the actual sketches I was damn near swamped,” Caniff wrote Kent. “Made it all right tho [sic] and it may (or may not) pave the way to a future contract to do one daily cartoon, which will be a welcome relief after years of daily illustration.”27

As if to not to jinx the deal, Caniff weighed the likely outcome of his 12 drawings in his letter to Kent, even hiding his secret desire within parentheses.

“My ambitions hardly run to the comic stuff but they do make fair money and it would give me more time for this sort of thing. (A single daily cartoon seems like a pipe dream to me. I can’t imagine having only that to do.)”

Whatever his misgivings, Caniff became the full-time artist on Mister Gilfeather on Sept. 12, 1932. Like Capp, he would later shift the strip’s focus. Under the name The Gay Thirties, Caniff continued to draw it until he quit the AP two years later.

Kent had little sympathy for Caniff’s ordeal in turning around the 12 Mister Gilfeather pages in the nick of time. Her next letter chastised him for taking too long with his latest assignment.

“Sorry, but the sketch for the story ‘A Frame for a Picture’ was not right as it did not emphasize strongly enough the doorway framing the room beyond,” Kent wrote. “The figures in the sketch were too prominent and the point of the story was lost entirely. Consequently, I had to have a rush job done locally. Too bad, but I must remind you that you have had [it] since August 20.”28

While Kent found the other sketches Caniff sent acceptable, she called him out for repeating a mistake he’d apparently made before.

“The lady rubbing down the chair was to have the names of colors printed on the cans beside her instead of ‘lacquer’ and ‘varnish,’ and I have told you before that varnish does not come in that shaped can.”

Criticizing an artist who one day would be lauded for the accuracy of his renderings and his attention to detail for forgetting what a can of varnish looked like is, in retrospect, amusing.

Despite the need to exert some pressure to keep Caniff on task, Kent did remember to sprinkle in some praise occasionally.

“The lady in her kitchen dreaming of Chicago turned out to be an elegant drawing and did wonders for the Fair story,” she wrote. “It’s fairly obvious by now, I should think, that editors print our stuff while still under the influence of the pretty pictures.”29

About this time, Caniff’s need for anonymity with his freelance assignments had started to become a real concern. The AP did not like to see its employees’ names in the newspapers of a competing syndicate. This proved a problem for Caniff, since the mats Save the Surface was producing were distributed free of charge to newsrooms across the country.

Caniff began leaving his signature off his freelance work for Kent or used a pseudonym. In the case of the booklet More Color Magic, he was credited as “Don Summer.” He also began signing some of his mat drawings with a pair of stylized “S”s.

More Color Magic sprang from the success of the stories told in the Color Magic radio show. The booklet contained one long story written by Kent and illustrated by Caniff.

For the cover artwork, Caniff drew two cartoony painters lifting the windows of Mrs. Rutherford’s house as if they were eyes having flabby skin stretched back. He also provided portraits of the landlady and her tenants.

When the Save the Surface Campaign decided to republish More Color Magic two years later, Kent sent a telegram to Caniff, who was drawing Terry and the Pirates by then, and asked if they could include his real name in the reprint since he was no longer working for the Associated Press. The artist gladly gave his consent.31

Through 1933, Caniff continued to take freelance assignments from Kent, even as his AP workload grew heavier. In addition to Mister Gilfeather, he began illustrating the children’s feature Puffy Pig in March.

“I have always had a yen to write and now I am doing a daily feature in xxxx rhyme (My God! I don’t even know how to spell the word.) It is kid stuff but has to be kept smart enough to catch the adult as well,” Caniff wrote. “I’ll send you tear sheets tomorrow.”32

The big event for the year was the debut of Caniff’s first, multi-panel daily comic strip, Dickie Dare, on July 1. The strip told the tale of a young boy who was inspired to go on imaginary adventures based on the books he was reading.

“Dickie has gotten off to a most pleasing start,” Caniff said, in a letter to Kent. “Quite a mess of papers came into line right off the bat and the procession is still moving. One big sock in the jaw was that the NY Sun failed to fall for it. I was counting on the Sun for a Metropolitan showing and they let me down. But so it goes. They may still fall for it. Who knows. It has hit pretty generally all over the country tho [sic] and that is most gratifying.”

By year’s end, the weight of drawing three daily features appeared to be having an effect on Caniff. In a hastily handwritten note in December, he apologized for turning in an assignment late. He needed to get ahead on Dickie Dare.33

Caniff poured all of his effort into Dickie Dare, shifting its focus. In the spring of 1934, he introduced the character of “Dynamite Dan” Flynn, a world-traveling adventurer. In a plot twist that would be tough to sell today, Flynn convinced Dickie’s family to let him take the boy with him the next time he shipped out. They agreed and Dickie Dare stopped being a strip about a boy’s daydreams and became one that chronicled Dickie and Flynn’s action-packed, globetrotting adventures.

In September, Caniff notified Kent of an address change. He had rented an office at the Daily News Building with Noel Sickles.34 The Associated Press needed someone to take on the general assignment artwork that Caniff had left behind when he agreed to do Puffy Pig. On Caniff’s recommendation, they hired Sickles.

With the new office and the shift in focus on Dickie Dare attracting the attention of the Chicago Tribune-Daily News syndicate, Caniff had set himself up for the next stage of his career, the one that would bring him his most fame.

It was about this point that Kent accused his work of being too “cartoony” and lacking “the old ‘Caniff Sparkle.’”

Three days later, feeling “conscience stricken” after her previous “scathing remarks,” Kent dictated a new letter, complimenting the artist on some drawings he’d sent her.

“Don’t mind my harsh words too much, but be artfully careful not to lose that ‘Caniff Sparkle’ in your work,” she repeated. “That’s going to pay you big dividends some of these days.”

But in the postscript, Kent couldn’t resist one final playful dig.

“P.S. — Regarding the Caniff Sparkle — Miss McElroy, my Good Man Friday, has always felt your pictured gals were closely akin to McClelland Barclay’s lovely, lithe, and long-legged dames. However, even her list face fell when she beheld the last consignment of Caniff Brain Children. Put that in your bustle and shake it!”35

Caniff replied to his editor’s stinging critique.

“My word, lady. You can make me feel better and worse in a single letter than anyone I know,” he said. “But I can take it and I hope [to] make use of it. All in all, I think your criticism was well taken. I have been doing this comic stuff for so long that it is no wonder I have become stale around the edges.”36

Earlier in the month, Caniff had mentioned in a letter that he was “dickering with the Chicago Tribune-Daily News syndicate” about a new feature for them. In addition, his contract with the Associated Press would be up on Oct. 15. If he signed with the syndicate, he’d leave the AP.37

The artist responded to his editor the day before his contract with AP expired. It contained a rough pencil sketch he’d drawn for the “Hardesty story,” his current assignment for Kent. It showed a woman sitting at a desk surrounded by items that could be painted. Along with the drawing, he delivered the news that the deal for the syndicate feature had gone through.

“I will tell you all about it when it is signed and sealed,” he wrote. “I don’t have the name on the dotted line yet. … And until that happens I take nothing for granted.”38

After thanking Kent for the check she’d sent him, Caniff added that it had come at a “most opportune time as is usually the case.”

On Oct. 22, the first installment of the daily Terry and the Pirates comic strip debuted, changing Caniff’s fortunes forever.

Unfortunately, the artist found himself in dire financial straits again. The Associated Press had paid him in advance for Dickie Dare, the strip he was leaving, and his first royalties for Terry were weeks away. He desperately needed any money he could get.

Perhaps this is why the artist found time on Oct. 31 to dash off an itemized invoice for his editor. The letter from Kent’s files includes pencilled notes by Kent or her assistant pricing each of the items and subtracting a $50 advance she’d already sent him:

Mast head and ears ($20)

House, painter, proud owner and wife and dog ($15)

Indian 1 col. ($7.50)

Home decoration 1 col. ($7.50)

1/2 cols of Trigg and Dewar ($10 + $5)

Radio head ($10)

Radio listener cutout ($15)

Portrait of Trigg ($15)

This wasn’t the first time a check from Kent had saved him from the wolves at the door.

Caniff also took the opportunity to provide details on the new direction his life had taken moving from the AP to drawing a new comic strip for the Chicago Tribune-Daily News syndicate.

“The strip has been running in the News here since Monday the 22nd,” he wrote. “The color page starts December 9. I like these people and I feel I shall be happier here. They are so much more human about their business, treating the artists more like the specialists that they are rather than as hired hands.”

After promising to send Kent proofs of Terry and the Pirates, Caniff asked the editor when she and her new husband would be in Manhattan again so they could throw a delayed wedding celebration for them.39

Producing and promoting Terry and the Pirates consumed Caniff’s attention and he had to cut back his freelance work, although he would gladly draw occasional sketches for fans and groups like the Boy Scouts or the American Red Cross in years to come.

While their professional relationship was over, Kent and Caniff continued to correspond privately over the years. They would recommend to each other history books they were reading or talk about their work.

When the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City hosted an exhibit of Terry and the Pirates artwork in December 1940, Caniff sent Kent an invitation to the private viewing. Although Kent and her husband couldn’t make it, she sent a message by telegram: “All good wishes. Would give a pretty penny to be present.”40

Kent became an avid reader of Terry and the Pirates, and over the years would send Caniff newspaper or magazine clippings of stories about him or the strip.

“Can’t tell you how tickled I am over the success of your strip and how pleased I am every time I hear praise voiced for it,” she wrote in 1940. “You are doing a simply elegant job. Your strip has so much human interest, swell character delineation and dialogue — not to mention the fine composition with which you endow your ‘pitchers.’”41

Kent continued to write articles about home decorating for magazines like House Beautiful and Better Homes and Gardens. She retired from the National Paint, Varnish and Lacquer Association in 1960 and became a community activist in Alexandria, Virginia. It was there that Kent became a charter member of the local chapter of the National League of American Pen Women and helped launch the Capital Speakers Club and the Welcome to Washington organization.42

In much the same way Kent had helped him out, Caniff reached out to his old editor in 1938 to recommend a young artist who was looking for freelance work.

Alfred Andriola had been working part-time at Caniff and Sickles’ studio, acting as their secretary and picking up cartooning tips more through osmosis than actual instruction. Andriola would go on to draw the Charlie Chan and Kerry Drake comic strips.

“I shall never forget how much it meant to me in those dreadful days after the Dispatch blowup to have your continued confidence and encouragement,” Caniff wrote. “That work from you paid the sheriff when the entire Caniff world was tottering badly.”

* * *

The post The Cartoonist and the Paint Lady appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment