The Belgian cartoonist Olivier Schrauwen’s latest graphic novel, Sunday, recently completed as a four-issue Risograph serial published by Berlin’s Colorama Books, shows an already great artist reaching even greater heights. The book’s high concept is one so obvious that most comic book lovers have probably daydreamed about something similar: Sunday follows a fictionalized version of Olivier’s cousin Thibault through a typical day in the life, during which he wakes up, putters around the house, gets drunk, puts off doing any work, fails to make it through a single sentence of the book he’s reading, gets stoned, and interacts with absolutely no one. Simultaneously, Thibault’s friends and relations are planning a surprise birthday party for him, descending on his lonely apartment and colliding with one another.

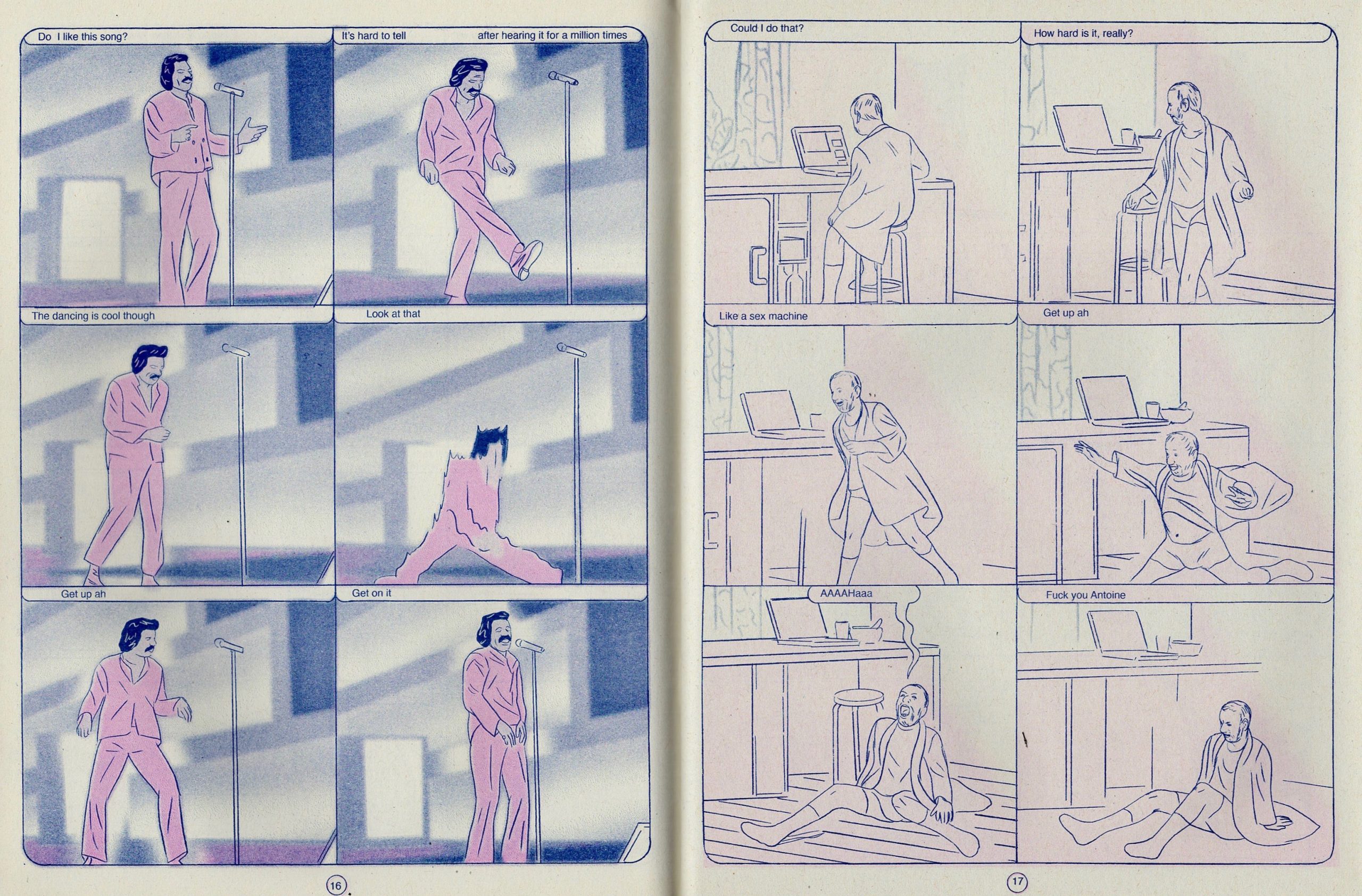

This is hardly wild or complex stuff, but what Schrauwen does in the telling of it is what makes Sunday brilliant. The book endeavors to depict one full day, not just in the life of its protagonist, but in the stream of his consciousness. As Thibault shambles through his many ways of doing nothing, we see him get songs stuck in his head, unearth and repress embarrassing memories, speculate wildly on grisly fates his girlfriend Migali may have encountered on the trip to The Gambia she’s returning from, mull at length over which hilariously titled porn clip would be most suitable to masturbate to, and, in a sequence that I think perfectly captures the complexity of what Schrauwen is taking on, struggles to compose a text message to Migali that asks what time she’s returning home without making it obvious that he’s forgotten. (The neon pink panels represent Thibault’s fading memory of a recent drunken escapade with his cousin Rik, rhythmically reasserting itself and being pushed away.)

Through Thibault’s meanderings, Schrauwen layers not just the journeys of his friends, but the equally banal doings of neighbors, passersby, and even the local fauna, following a mouse’s white-knuckle speedrun through a neighborhood filled with cats. Sunday not only takes a most convincing whack at the portrayal of nothing less than human consciousness in comics form, it weaves strand after strand of narrative and anecdote into a book that ends up encompassing the life of an entire city district and social circle over one unremarkable yet epic day - and winds up feeling a bit like a plainspoken, unostentatious comic book version of James Joyce’s Ulysses by the end.

Every thinking cartoonist has tried to get at what Schrauwen does here, the rendering of thought itself as lines on paper, but few have made as much progress as this blunt, direct, at times almost bloody-mindedly literal book does. I’ve been obsessed with this comic since I read its first issue a few years ago, and when I got the chance to ask its maker how he did the making, I couldn’t resist. Olivier spoke with me via videochat from his Berlin studio in late September, shortly after the final Colorama issue of Sunday was released; the transcript below has been edited for clarity and concision.

-Matt Seneca

* * *

MATT SENECA: So when you were first thinking about doing this comic, did you mainly want to do the one day in the life, second by second thing? Or did you have scenes or ideas that you wanted to get out there and then realized this would be the best way to do it?

OLIVIER SCHRAUWEN: It was definitely the first thing. I thought I'll make something as bland as possible, so if nothing happens in it, even better. I remember having the idea-- it's not even an idea, it's just let's make something that goes from second to second, or from minute to minute, all day, and make it very uneventful. Take a very middle of the road kind of person that has no special qualities, just a normal guy. And for some reason, I found this exciting. I think early on, I also thought I can have this pattern, like the way you have these consistently reoccurring ideas, I can make it into this kind of a pattern and work with this pattern, and then maybe add something else and work in a more musical way or something, a more abstract way. It's not about the content of the story, it was more about the form first.

Mm-hmm. How did you build the characters within that? You have the main guy, Thibault, but this is maybe the biggest cast you've had in a comic. There's the guy at the bar, there's the little girl, there's the cat, there's the mouse…

Cats and mice. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[Laughs] So what made you decide on the cast you had? How did you decide “I need another character, what if I put this in?”

Well first of all, this main character, I immediately deviated from my initial idea to make him very bland or somewhat robotic. I made him a little bit closer to what I am, instead of just making like an everyman. And then, because he's a bit uptight, I needed someone who was like the opposite of that. I know some people like the other characters, but not exactly one per, they're like Frankensteined out of several people I know. First I had his cousin, and then I thought maybe he met some old girlfriend of the main character. And he has [his current] girlfriend. So those are the main ones. That was all quite quickly there, but it was not so defined yet what their characters would be from the get go. The first issue, we only see Migali [Thibault's girlfriend] in the end, but even then I didn't know for sure how she would act in certain scenes. That grew a bit, but it felt kind of natural because it's familiar characters from my own life in a way.

How much writing do you do beforehand, before you start making the comic, and how much do you improvise when you're doing it?

It depends. In this case there was no writing at all for the first issue, I just had the basic ideas, and the story is so simple that I didn't have to plan it out. There was nothing that had to line up or had to be exactly in a certain way, so I could be kind of loose. And then from the second one onwards, I put a big paper on my wall and just-- I have timelines for one character and the other, and I had these intersections where things had to line up.

And I often re-edit; if I go wrong somewhere, I re-edit it. I spend a lot of time on re-editing things, just because I want to be loose and kind of improvise when I work because it gives a better result. And then if I go off the rails or go somewhere that doesn't work, then I just go back and fix it. It’s just a matter of putting it in the right order.

Does the book get bigger as you go? Or when you're editing, do you cut stuff down and say, I gotta lose this, I gotta lose that?

It's always cutting down. Like in the middle of the book, I had this section where I thought, here I will have as many elements going as possible. And it was very baroque, much more than it is now. But then when I read it, it was just-- it turned into mush. It was impossible. I was juggling too many things and it didn't work. So I had to go back and cut a whole part out and then take it to another issue.

Were you worried-- first of all, did you get bored making this? And then were you worried other people would get bored, following the characters second by second?

I don't really-- when I get bored, I just put it aside and work on something else. But of course I was worried that people would find it boring. And some do, [laughs] but yeah, you try to find ways to make sure that it stays engaging - you try to, but everybody has different tastes. I was maybe more worried that people would find it too annoying, but then I thought it has to be annoying sometimes, and people have a different tolerance for this kinda thing, so it depends. Some people find it funny, and some are a bit irritated with the main character, and at a certain point they have to put it aside.

Talking about that, do you have any sense in your own mind of how this is gonna read as one book? Like for me, I could see getting irritated with Thibault, but because I was only reading an issue once maybe every year or even longer in between, it was perfect. That amount is the perfect amount of him. And then you wait a year, you forget about things, and maybe a month or two before the next one comes out, I was ready to go back and start getting annoyed by the guy again.

Yeah. It's definitely made in a way that-- like now I'm compiling the book and it still has the format of the different magazines. In one of my previous books [Arsène Schrauwen] I put a text, like, “you should put it aside now”. Didn't do that [here], but I work in short chapters that kind of suggest how far it can go; I try to suggest the places to pause in the layout, so I didn't try to really make a book that forces you to read the whole thing [in one sitting]. It can't read like that, I think.

No, I mean, this is really dense comics. It would take a long time to read it that way. When you talk about wanting to improvise, and going back to edit things later - when you've got the blank page in front of you, what comes first? Are there drawings you wanna make or is there a page structure or a grid you want to do? Or do you put the words on the page first and let that lead you?

Well, I always put the words down first, and then I think of the particular layout of the page. But I always know where I am in a sequence. So I always think of the continuity, and it has to fit, so there's not that much freedom. But I never know exactly what [the final] text is I'm gonna put down and which association it has, so you can do a lot, even if you are within a story that's already somewhat fixed.

So you edit the text too, once you've got all the drawings down? Put new words in?

Yeah, I'm constantly doing that. If I haven't worked on it for a while, I read it and I get very annoyed, and I make a lot of notes. I don't know. I sometimes hear about comic artists who will make one page in the beginning, and then they skip a few scenes because they don't know exactly what to do, and then they go further in the story. I can't do it - I have to be, like, linear. It's kinda like a performance, I'm acting it out as I'm drawing it. I get confused if I skip around.

That's interesting you say that, because one thing that I think most comics do a really bad job with when they try to do it is showing music.

Yeah.

And there’s a lot of music in this comic, like way more than your usual. And I think it's actually done pretty good. That's a performance too - and I think that's why comics are so bad at it, because comics are so rigid and composed and you can see the structure, and music is just-- you can't see it at all. It's just there flowing in time around you. Was music something you were excited to use comics to show?

I spent a lot of time, especially when I was younger, trying to make music. I was almost as much occupied with that as with making comics. So it's just very natural to think in a musical structure - we have a little crescendo here, and then you have some tones match up, and then it goes down, and then there's a little improvisation or whatever. That's why I always look at the continuity and treat it very fluidly - except when it has to break up for some reason.

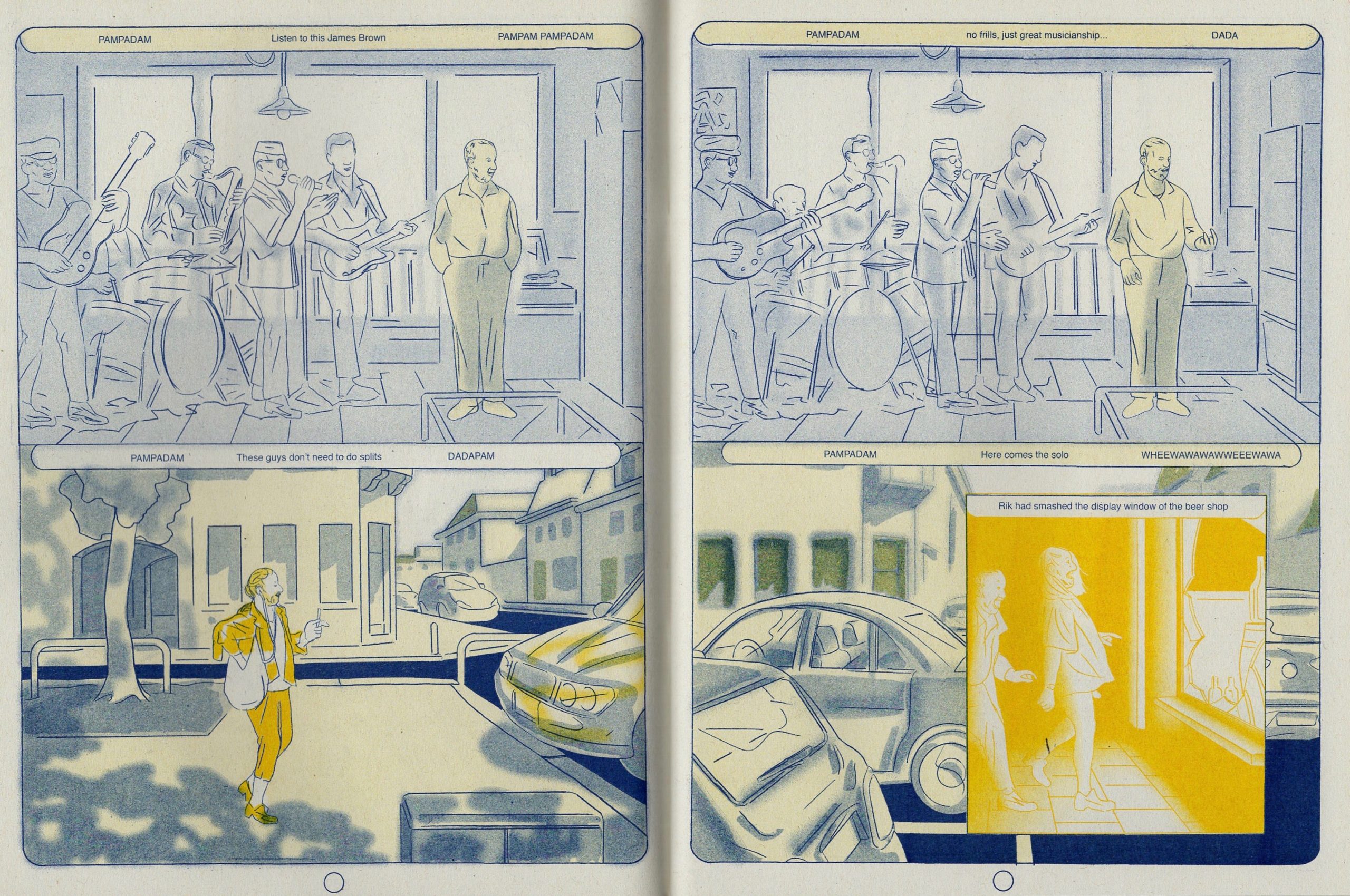

In this book there's a lot of references to more minimal kinds of music, because I was thinking of certain composers that start from a concept and then make, with very simple components, something that's engaging - but in a minimal way, somehow. Even James Brown is kind of a minimalist, so I was thinking about these kinds of things. But I work very spontaneously. I don't really set out my plan, I have-- you know, I just have a hunch that it will be interesting, so I go a certain way.

Do you have parts that are more concrete? Like where you know exactly how it's gonna look or what they're gonna say, and you sort of string along until you get to one of those? Or is it all just page by page figuring it out?

I always have a few scenes that are really elemental to it, like the ending scene in this last book, and I work towards them. I have to have these scenes that I am almost certain about, that they will be good or work dramatically or whatever. So I really anticipate-- I'm looking forward to draw them and to get there, in a good way. And then, to be able to draw them doesn't always work. Sometimes I'm working towards something and then when I'm finally there it's like, hmm, doesn't have the right impact, then I have to rework it. But generally I have quite a good hunch where I want to go, which key scene I want to work.

Besides the ending, what were some of the scenes that you were excited about drawing in this one before you started?

Well, the bar for instance. [Pauses] It's a bit difficult… there’s one that, when [Thibault] finally decides to go out of his house, his neighbor is there. [Laughter] That was definitely one that I was working towards. And then Migali getting to her plane was also one that I was really fussing about a lot, to push it as late as possible.

How do you compose these images when you're actually drawing?

I always make a small thumbnail. At the end of the book, I just took the thumbnail and blew it up and then drew on top of it. I'm kind of sorry I didn't come up with that earlier, because that seemed to work very well. The thumbnail is so small, the images you make-- and I make them very quick, but often the pose is much more accurate in this drawing. So I imitate with my more realistic, clean drawing, but that takes a while. I try different things, what will work best, but I often go back to the first idea. Maybe doing it so long, comics, I kind of have an intuition of what will be best. And then when I overthink it, it's too labored or too thought out.

How about drawing for Risograph? I feel like almost all of your comics, you've done a Riso version [as the first published form of the work] for like 10 years now. What is it about that tool that you like?

It limits me. Like, the fact that I can only do two colors - I could do more, but that would be too inconvenient. That's the practical side of it, that it has to be simple. The fact that the machine itself gives this texture on the pages. Before I used a Riso I was always fussing about the colors, and the texture of the paint, or the digital. Now it's just up to the machine. So there's one thing less to worry about, and then I see it and sometimes it looks cool and some it's like, what the...? [Laughs] In general, I like the fact that it has this mind of its own a bit. So yeah, just less things to fuss about.

Do you have other people who use the Riso that you really like, or wanna make comics that look like them or something? A ton of people are using this tool now.

Yeah. Now I’ve seen so many. I was just reading this. [Holds up a copy of Lagon Revue’s Plaine anthology] This is not really Riso, but the previous [anthologies published by Lagon Revue are]. The stuff that color does, I feel like I've seen all the possibilities of this machine now. There's many people working, making work that I really find beautiful. Like I saw this book by Melek Zertal [Together, also published by Colorama], it’s gorgeous how it's printed. But I have kind of my own area - when I was younger, I was more inclined to, when I saw something amazing, emulate it somehow. Now I'm more-- I have to work on my own.

Do you feel like you're part of a scene with other cartoonists? You talk about the Lagon anthologies - do you feel like part of a scene with those guys? People doing, for lack of a better word, experimental comics in Europe?

Well, those are the only people I'm in contact with. But that just happens organically. Maybe if I go to Angoulême I'll see, like, a famous comic artist, but I’m kind of out of touch with them. And then maybe it's a little bit easier when I go to [Comic Arts Brooklyn, currently on hiatus] - then it's easier to talk to Daniel Clowes or to Chris Ware or something. They're more accessible than-- in France, for instance, I don't know any of these big shot comic artists. It seems a little-- like a little bit more segregated somehow.

But do you feel a connection to the work that appears in those anthologies that you're in?

Yeah. But that's the only thing I read in the end. Except when I’m feeling nostalgic, I'll take some old comic from Belgium or something - but I'm kind of out of touch with everything that's out, outside of people I know. But I feel also when I meet people who work for similar editors, who are in the same niche, that there's immediately some kind of connection - you have a shortcut to kind of a friend, or a friendship. Yeah, it's very easy to get along with them, 'cause there's often similar tastes and so on. There’s an immediate familiarity, even if they’re from Taiwan, Finland or wherever.

What are some of those old comics that you keep coming back to for inspiration?

I'm always going back to Moebius for some reason--

Well, he's the best!

[Laughs] Yeah. Yeah, I don't know, I've been reading him since I was kid, so those books are like, very charged. I recently bought some new ones too, where I don't have this memory of being in my parents' house… and instead of doing my artwork, I was reading these comics. Yeah, I love it. I’m also reading Chaland, Yves Chaland, that kinda stuff. Mostly French or Franco-Belgian. I don't really know the, like-- I'm not familiar with Marvel Comics, it's really a blank spot. One day I should get into it, but I dunno where to begin. It's too much.

I'll send you a list of stuff. Maybe I can mail you some, I got a million Marvel comics at the house. [Laughs]

Even the classic-- like Kirby, or I don't know--

That's the good stuff. The stuff they put out these days is not worth your time, it's pretty bad. But that's interesting that you say you're always coming back to Moebius, because, you know - on a surface level, his and yours are not particularly similar.

Yeah.

What is it about his comics that that keeps you coming back?

It's so immersive, and I remember it was the first real adult comic I read. My dad had this Blueberry [album], and then I suddenly realized that the Blueberry guy was making all these other comics. And that was the first time I read something really unconventional, in the sense that stories were so immersive. Also, how he draws, it's like Fellini said - it's like “Super Cinema.” It's so-- it's better than cinema. It's more studied, the way he draws, he has certain tricks that he always does, like a lot of [overhead] shots. There’s a set of those, but even if you would imitate that, you wouldn't have this really immersive effect. And then I was reading this book I’ve had from him since I was a kid, it's like interviews [Moebius, entretiens avec Numa Sadoul]. It's a very thick book, and it goes into his spiritual life. And he was always living in in, like, sects. Well, not really sects, but in-- how do you call it?

Communes…?

Yeah. And then I realized that, even when I was a kid-- it's in French, this book, and my French is very poor. I was trying to read it, and I remembered things I read like 30 years ago that I was thinking about, but didn't understand.

That's interesting that the first thing you mentioned about Moebius is the immersive quality, because I assume that's something you're striving for in your work too. This comic specifically, Sunday, is so immersive. Is that something that you're going for? Do you want-- well, I don't know… yours have a funny quality of both being immersive and also kind of calling attention to the artifice of reading a comic.

Mm-hmm.

Are you trying to, like, move between those two poles? Would you prefer to do one or the other? Or is it not something you think about?

No, but I'm always thinking about the form of the thing - and when I was younger, especially when I was in my 20s, I tried anything, and almost nothing worked. But my intention was never to draw attention to the formal, it was just trying to find a way to make it more-- more whatever I was feeling about the scene. If it could be more tactile and you felt it - you feel it more, and then therefore you can stick with it. Especially if there's a lot of-- certainly in this one, who wants to spend his whole day with this guy?

So I have to-- yeah. I always test my comics, I show them to my girlfriend and I watch her reading it, and I have to sit next to her because I'm [pantomimes studying her face]. It's annoying, some friends find it annoying that I have to look at their face while they're reading, but I'm just trying to find out where their attention wavers or whatnot. The things where the faults are, and just the reading experience.

Do you think that if you get to, like, the ultimate level of skill you're aiming for, you'd be able to put anything in a comic and have it be entertaining and something people would wanna read?

[Laughs] I dunno. That’s not really what I think about. There's things I want to make stories about, but I don't know how to do it. I just-- I can't see it. I'm waiting until I have some idea of-- maybe I take this strategy and it'll be possible. But it always differs a bit, how you approach things, so it's not like one thing that I am perfecting, necessarily. It's more like, you want to go somewhere but don't know how, because it's too weird or banal or difficult or painful or whatever. And then you just wait for inspiration. That really sounds a bit stupid, but it's really-- sometimes you have to wait for inspiration. You have to keep on working, but the truly interesting ideas can’t be forced.

Are you conscious of themes that pop up again and again in your work?

Mm, yeah. [Laughs] There's always the same kind of elements coming back. I don't know if I really like it, but I'm also not avoiding it. I see that there's parallels between this book and Arsène, the characters are almost in the same predicament. And then I think, okay, that's a parallel that's kind of going back through the ages to his grandfather. But if I feel that thematically I pop up in the same places I've been before, then I'm not on the right track.

But I-- I do think about it, because you see a lot of it in novels also. Like you have writers that are very exciting in the beginning, and the work is varied, and then suddenly at a certain point you can almost make an AI program-- an AI program would be able to make a more or less convincing Murakami or something. [Laughter]

Yeah. I don't think you're there yet, I don't think you have to worry about that.

I have to be wary. But I always break up my work. I always spend time doing other things - maybe jobs, or now I try to do some animation to clear my mind.

One of the themes that I keep noticing, probably because it's funny and appealing to me, is-- in English we call it "boorishness."

Hmm.

Like, you know, drunkenness or being a fuckup. Especially if you're a guy, like this male behavior of lazy, drunken, not really caring about other people - you know what I'm talking about?

Yeah, of course.

So like: this one [Sunday], your “Cartoonify” comic [originally published in Lagon Revue’s Volcan anthology, collected in Fantagraphics' Parallel Lives], which is one of my favorites, Arsène, and-- Portrait of a Drunk [a collaboration with Jérôme Mulot & Florent Ruppert] is the name for it in the States. What appeals to you about these characters, and showing this kind of behavior in comics form?

That I really don't know. I also ask myself why always this kind of character. Am I trying to redeem him some way by putting him in a funny comic? Or do I feel guilty about some of my own behavior or something, and I try to somehow salvage it? I can't-- I really don't know. Besides, of course, that it's funny.

This kind of boorish character used to be much more commonplace in comics and other media. Now it’s totally outmoded, a lot of people are fed up with it, and understandably so. But apparently in my mind the wrongness of this character opens possibilities. To place this kind of dude in a contemporary context.

One thing I don’t expect from the reader at all is for them to sympathize or even empathize with the main character. The comic should work independently from that.

As a reader it can be hard to get into a book if the main character is unlikeable. So it seems to be one of these things, like having a very bland storyline, that seem work against me, but that I try to work for me.

Yeah.

And it's kind of what I grew up with in Belgium. I must say, most people's behavior was kinda-- especially if I compare it to how people behave nowadays? I remember when I started going to, like, workshops, comic workshops, and I would visit art schools with younger people, millennials, and I was so amazed. Everybody's so nice! [Laughs] They're so polite! And I was really happy about that, because we used to be so kind of nasty, and… and un-polite was the norm, especially in Belgium. The lack of decorum and excessive drinking and all this stuff - it’s just the most banal and commonplace thing.

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, I don't know, but that's not a good answer. I don't really know.

That’s interesting though, 'cause I think you're right. I work at a college in my day job, and all the kids are so thoughtful and nice! And then I think about myself in college, I was a drunken fool 100% of the time. And, I don't know, in a way I look at your books and I recognize myself, or maybe a younger version of myself, or a way I let myself get a couple times a year. But I wonder if that even makes it funnier to people who don't engage in this behavior at all? Like, nice young kids who are just walking around being nice all the time - maybe they think it's totally hilarious that anyone would ever act this way!

Yeah. Yeah, well, that's what I was thinking about, I don't know many people who are in their 20s, for instance, or teenagers even. I have no clue how they would react to it. Maybe it's really, like, exotic almost that you can be like that. [Laughs]

You also mentioned maybe trying to redeem that behavior a little bit by putting it in comics.

I-- I find this a bad idea. That's why I hope it's not the case - it's not something you should try, I think, right?

Yeah. Comics as therapy, that's not gonna lead you anywhere good. But it's interesting because in all your other ones–Arsène, some of the short ones you've done for Lagon, and definitely in Portrait of a Drunk, where he suffers the actual torments of hell–there’s some kinda redemption through punishment. At least, they're punished for their actions. And in this one, there's nothing even close to that, unless the punishment is Thibault being his boring, annoying self. That's not a question, sorry.

Well, I dunno. I mean, [his friends] know he's a jerk, probably.

Yeah.

And also, he's isolated throughout the book. So you see the worst of him, and it's like a day that-- if you would see him in a normal situation, he would be more polite and he wouldn't be such a dick in a normal conversation among his friends.

Another thing that comes into your comics pretty frequently, and this goes along with the drunkenness, is trying to show altered states of consciousness. Like in this one, when he smokes pot, the layouts get all swirly and strange. What's the appeal of that? It's another thing that comics tend to do a pretty bad job of, like music. But again, I think you do it pretty well. Is that a challenge that you want to take on? Or is it just where the story leads you?

Maybe what most appeals to me about it is that what makes sense about the story kind of starts to disintegrate, and how rationality-- it always seems to be on a sort of a curve. Rationality, it's just an illusion. So I love it when it very gradually glides into complete nonsense. I dunno why, but I have this-- maybe not fear, but this suspicion that my rationality is very… very loose. [Laughs] Really, I shouldn't think about it too much, but last week two times I got the Wordle in one try. I thought if it's three times. I have to kill myself because this is, [laughter] this is not normal. I'm living in a simulation or something.

I think my favorite scene in the book is the one where Thibault's sitting in the bathtub trying to type a text message to his girlfriend, and it goes into this tiny little grid, like 64 panels on a page. And it's just him trying to find the words to not make himself sound like a fool and not make her mad or let her know that he's just been farting around the whole time she's been gone. When you're writing a scene like that, what's your approach? I mean, for me it's a perfect scene because I've done the same thing so many times. My girlfriend goes outta town for work all the time, and I've lived that scene 30 times this year. How does that go from an idea to what we see on the page?

Well, that was one of these scenes that early on I wanted to have, so I'm working towards it from the beginning. I dunno how long the sequence is, maybe 10, even more than 10 pages. So this is really what’s exciting for me - it builds up, and then I try to pace it in a good way so it gets [denser], and then I get to the page with the most images… and I realize that I can't stretch it out anymore. I have nothing anymore, and then I feel kinda disappointed, [laughs] that I can't push it-- I don't want to be annoying. It's not what I set out to do, to troll the reader or something, [laughs] but it has to be a little bit annoying, has to be. I'm not gonna exaggerate.

That's the one scene I've shown to the biggest number of my friends, and they've thought it’s just the funniest thing they've ever seen in their life. One of the first things you mentioned, though, was wanting to make something as dull as possible, or at least superficially as dull as possible. And I feel like this scene is kind of the perfect illustration of that. You stretch it out as long as you possibly can before it starts to break down. If you had to say - why is that something that you're attracted to, as opposed to something more exciting and action-packed?

I want to make it exciting in the end, but I want to have very little zeal in the story. Very, even-- no drama, nothing. So whatever tiny thing you do is very noticeable, and you can really see the art of it or something. I don't know how to say this, even… it's not confused by plot entanglement. It's just playing; seeing the tiniest of behaviors, or the most banal. And to be able to work with that you need, like, a clean table. I can't explain it very well, but probably Thibault’s Monday [immediately following the events Schrauwen depicts in Sunday] would be: first he'll have a party with his friends, then he has a hangover, then he has to get [his troublemaking cousin] Rik out of the house, then he will sit with his girlfriend, she'll talk about her trip, and then he will go to bed quite early, whatever. That's not a good template for this kind of comic where you really want to work with the rhythms and the patterning, and these little musical or abstract ideas wouldn't fit. So yeah.

Yeah, you still have rising action and everything. I guess the way I would put it is, there's, you know-- a kind of story that's super-manipulative. If you see a drawing of a crying guy holding a beautiful woman covered in blood, you're gonna feel a certain way. Everybody's gonna have the same reaction. Or, like, a zombie with its guts hanging out, reaching its hands out towards you, everybody's gonna have the same reaction. But with something like this, all the manipulation of the audience that's happening is being done through the formal elements of the comic, with just text and pictures, not the content. So I don't know, that's not a question either. I can see the appeal of doing something like that.

Yeah, it's manipulative. But I also always hope that the reader will read it in a way that says, "Ah, he's manipulating us, but he knows that we know that he's manipulating us." Or something that’s kind of collaborative or something. That it's manipulative, but in a kind of a friendly way. [Laughs]

Well, comics is sort of like a car, right? You need the reader to climb in and push the gas pedal for it to actually go. It's always a collaboration with the reader, 'cause they need to bring the images together. By themselves they don't make any sense.

Mm-Hmm.

I have this as a question just 'cause people must ask you all the time, but are your characters any relation to these people in real life? I know you use the names of your real cousins, real relatives and stuff. Is this actually what your real cousin is like?

Well, funny thing was, my cousin also lives in Berlin. When he came here, he stayed at my house when I was not here. And he found this comic, [laughter] and he read it, but he liked it. But he's not really-- he’d say "I'm more like Rik [than Thibault]," even though he is like a very sporty, fit guy. But certain elements, everything in the book comes from somewhere that's familiar. That was maybe the thing I struggled with a little bit in this book - that I'm not used to making the characters this realistic. And it's easy to be a little bit cruel with a character that's very cartoonish, but if they become more lifelike, then certainly there's different rules that apply. I had to think a little bit more about their psychology and their behavior. I had to be a bit more prudent sometimes, you know?

Were there moments where you had to get rid of something you really wanted to do, or that you assumed would always be in the comic, just 'cause the characters weren't leading you there?

In this one maybe not, but in Arsène it happened a few times. I tried the scenes a couple of times, but it was not right - emotionally it wouldn't click. It just was an abstract idea. But no, like I said, when you draw it, you feel like you're performing it a bit. So you're feeling a little emotionality of the moment, the way you’re feeling yourself - the story is absurd, but it still has to have a certain fit in the reality of this work. Maybe it happened also in [Sunday], but I can't think of that [passage] right now.

Did you have a favorite character by the end?

Anyone but Thibault.

[Laughs] So you hate your cousin now?

No, no. Not at all. I mean, I don't hate [Thibault the character], but he's not very pleasant. I had to translate the book to Dutch recently, so I had to go very slowly through it, and he really started to annoy me, and translating, very slowly reading it, I’d go, oh no, it's too much. [Laughs] At a certain point, he is particularly annoying. But then he trips and he falls with his nose against the wall, and it felt like a relief… [Laughs]

So you're still a little bit cruel.

A little bit of punishment here and there, that's necessary, I think. [Laughs]

Talking about translating, you mentioned that French is not your best language. But you’re rendering all your comics either into French first, or English first. Why do you do that? Why do you start in a language that's not your native language [Dutch]? What's the appeal of doing that?

I don't know if I really like it, I must say. You could say it's a limit, it's one of those limiting things. I would fuss over it a little bit more if I wrote in Dutch - the fact that it's in English, and I don't quite know what's right, is just practical. One of the things I was the most enthusiastic about, getting this Riso machine, is now I can make my own book and it has to be in English because I will be selling it to anyone [around the world]. So it's just practical. It doesn't make sense to make it in Dutch, then translate it to English, and then... yeah, it's just a practical thing to do.

Yeah. How much editing or fussing over it do you do when you know the book version's gonna come out? Do you bring somebody else in to help you with that, or just go with what you got?

There’s no one willing to do that! I show it to people and then they read it and say what they like. In this case, at Colorama, Johanna [Maierski, the Berlin-based Risograph printer/publisher who runs Colorama], she will go through it and then correct some things.

She has quite a big influence I would say. Because we’ll talk about certain aspects of the story, and she’ll help me make certain design choices. We’re friends and live in the same city; I haven’t had that kind of relationship with a publisher before.

But I don't have an editor that's really combing through the piece and is going through the minutia. It happens over time. Like now I [am translating the book into] Dutch. I will make some changes to the content because I now notice there's some mistakes. When I do it at Fantagraphics, then Eric Reynolds will help me. He’ll say, this is word salad, this is blah, blah, blah. So after a while, it gets a more definite form. But there's no real thorough editing. It's-- especially this, [holding up Sunday 5-6-7-X] I can't open it without seeing some mistake. [Laughs]

I worked on this literary magazine once that I had to make illustrations for, and I saw short stories by several authors, and the notes were still on there from the editors - and they combed through it sentence by sentence. Really thoroughly? This is so intensive!

That's one thing that's great about comics, though, is once you do a drawing - there it is, you know? That's what you got, and you can fuss over that one drawing forever or you can just go and make the next one.

Yeah. But fussing over drawings is-- I fuss over the structure and the sequences, how it reads, more than one guy who has a different nose in every panel and looks awkward. Yeah. Whatever. [Laughs]

So are you gonna redraw any of this for the book version?

Only in the first issue. I did all [the redrawing] in one day. I made some changes to things that are not quite correct. Like, I didn't know that Migali would have this amount of luggage, so I had to add some, and this kind of thing. Yeah. If I would work twice as long on the pages, I would get 'em pretty tight, I think. But I don't want to work so long on a page. It's just-- you lose all momentum if you take too long. I don't have the temperament to-- I wish I could draw a little bit faster, even.

There's more energy anyway, in a quicker drawing that's not so tight.

Yeah, I think so too. Yeah.

I mean, maybe somebody like Moebius can make an amazing energetic drawing with a million tiny little lines. But most of the time--

He was pretty quick himself.

Yeah, well, I guess he didn't pencil anything? He would just sit down and that was what came out.

Yeah, he would draw on the toilet seat in a metro station. [Laughter]

The last question I have for you is: you're pretty deep into your career now. I took my ruler and measured how much space on my bookshelf all your books take up, and you've got six inches of work sitting on my shelf. If you had to, how would you characterize yourself as a cartoonist overall? What kind of comics would you say you're making if somebody asked what you make?

Something peculiar and funny, or something. Yeah. I don't hate it, but it's, like - I never have a good answer. And then my girlfriend often tries to explain it to people, and then she also gets lost and then they forget about it. [Laughs] No, I can't really define it, but they're a bit peculiar, I think. I wouldn't say I'm really for-- some people will like it, some won't. It's limited, the appeal that they can have. It's… yeah, I don't know. It's difficult to say.

Even though I know I have a certain style and somewhat limited area I’m always working in, I don’t try to define it too much for myself. I’m always hoping to find ways to venture out to some other place.

The post “Something As Bland As Possible”: The Making of <em>Sunday</em>, with Olivier Schrauwen appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment