Alfredo Castelli, a larger than life figure on the Italian comics scene, died on February 7, 2024. Born in Milan on June 26th, 1947, his career spanned nearly 60 years. Aside from being one of the most prolific Italian comic book writers, with numerous popular characters and thousands upon thousands of pages to his credit, Castelli was also a comics historian and founder of several comics magazines. His influence has been felt on generations of readers, artists and writers.

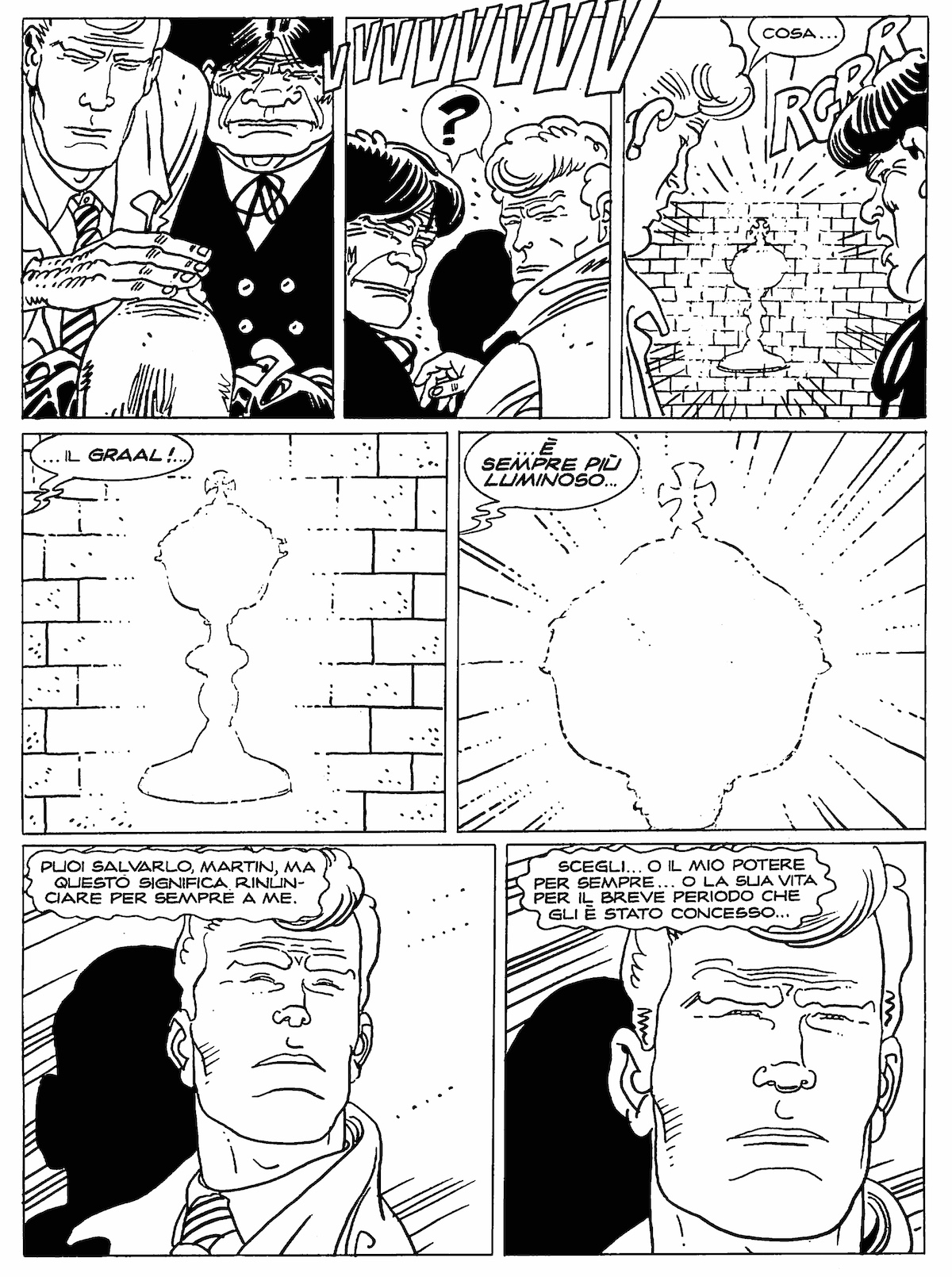

To the wide public, Castelli is best known as the creator of the popular and long-running monthly series Martin Mystère for Sergio Bonelli Editore, the same publisher as bestsellers like Tex and Dylan Dog. Known by the moniker “The Detective of the Impossible,” or to his fans as "BVZM"—Buon Vecchio Zio Martin ( “Good Old Uncle Martin”)—the character debuted on Italian newsstands in April 1982. Martin Mystère is an archaeologist and anthropologist who deals with bizarre and inexplicable cases that might involve the lost city of Atlantis, Arthurian mythos, Nazi secrets, space aliens, or other esoteric mysteries. Published very briefly in English by Dark Horse as "Martin Mystery" in 1999, the series might be described as The Twilight Zone meets The X-Files meets Indiana Jones.

Martin Mystère made its debut only three months after the release of Raiders of the Lost Ark, though it actually took no inspiration at all from the Steven Spielberg film, since the concept was reworked from a short-lived Allan Quatermain magazine feature Castelli created with the artist Fabrizio Busticchi in 1978. This premise had such great potential, and touched on so many themes and topics dear to the writer, that Castelli felt it would be a shame to let it go to waste, so he pitched a new version of it to Sergio Bonelli. The name was changed, as was the character design - devised by Giancarlo Alessandrini, who became the regular artist for the new series and is still responsible for its cover art today.

Initially, Martin Mystère was pitched to Sergio Bonelli as an action-packed series, in the signature style that had made the publisher a newsstand leader with its 100-page pocket monthlies. However, after a handful of issues, the true spirit of Alfredo Castelli took over the project, and Martin Mystère became quite different: one of the sharpest, most cultured, most verbose series ever seen in Italian comics.

“Sergio was certainly expecting something more adventurous,” Castelli said of his publisher in an episode of the RAI public television documentary series Fumettology, “and it was a shock for him to see the character using a computer in one of the first issues, and becoming really verbose, resembling me, and being a homebody compared to all the other heroes to which the publisher was accustomed.” Later, over the years, Sergio Bonelli would joke about being 'cheated' by Castelli, who promised a hero and wrote a lazy, loquacious character instead.

Martin Mystère found strength in this diversity, and proved a fundamental player in the growth of Sergio Bonelli Editore - which is to say, in the history of Italian comics, as SBE is such a major actor. Mystère was the first Sergio Bonelli character to live in a contemporary, real setting (New York City), followed a few years later by the London-set pop phenomenon Dylan Dog, created by Tiziano Sclavi in 1986. Unlike his predecessors, Mystère was basically a regular person with a regular job, a writer and academic. Really, he was an idealized alter ego of Alfredo Castelli: taller and more handsome, though no less smart and cultured. Only two of the first 50 issues were not written solely by Castelli, and he retained editorial control over who was writing and drawing the stories until the day he died. It is no coincidence that to many admirers of the series—including those writing this obituary—the best Martin Mystère stories are those written by Castelli.

For these and many other reasons, Martin Mystère is considered by many as a junction point between mainstream popular comics and 'auteur' comics in Italy - two categories that during the '70s and '80s were clearly distinguishable, both in storytelling and editorial terms.

But Martin Mystère was also a natural evolution in Castelli’s career, one devoted to curiosity, study, divulgation, and to the creation of unconventional adventure stories - and comedy as well. “If there is some mockery, I’m having fun,” Castelli said in a 2016 interview. “The other stories, the serious ones, they’re a pain in the…”

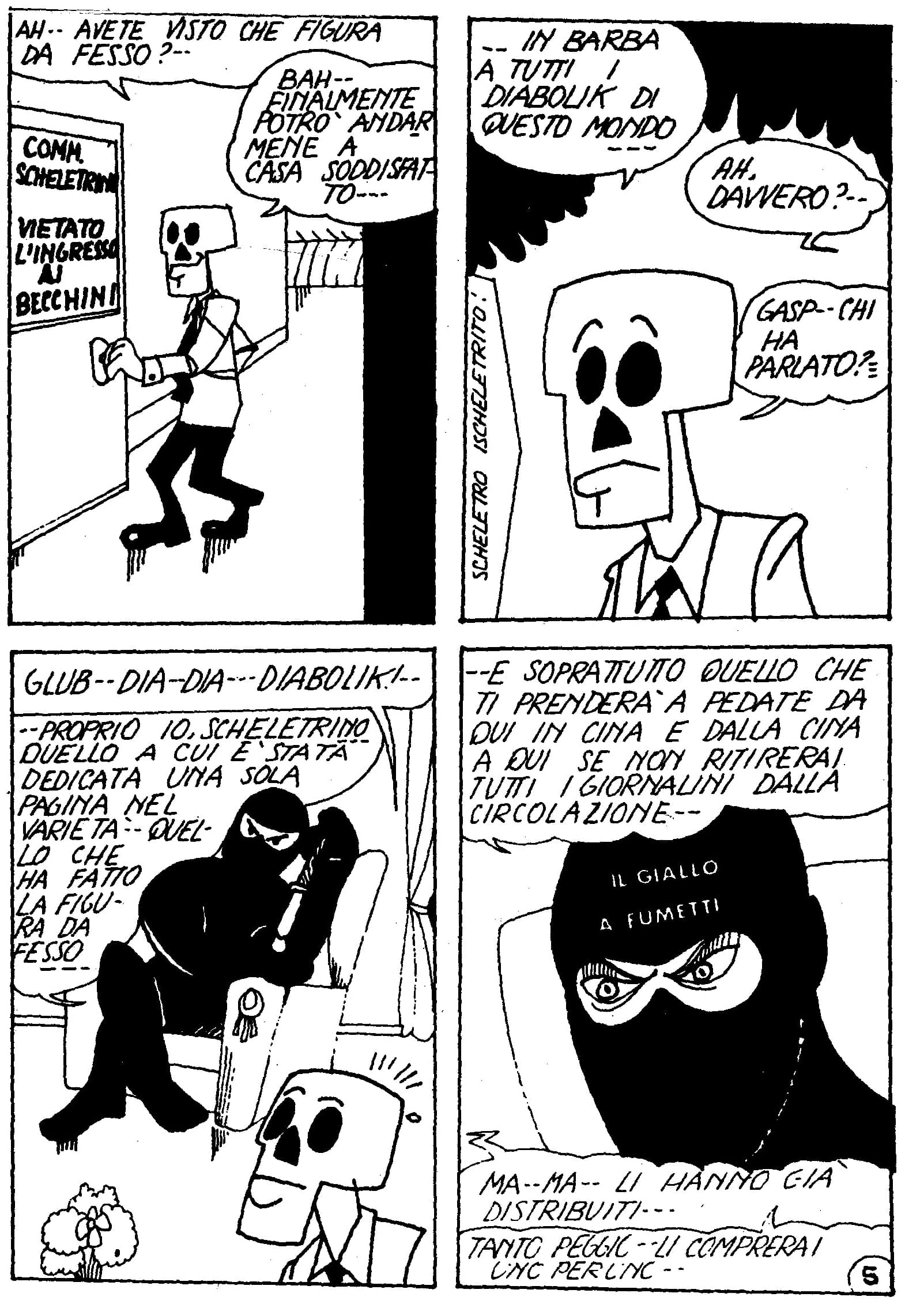

Alfredo Castelli made his debut as a comic artist in 1965, when he was only 18 years old, in the pages of one the most famous Italian comic book series, Diabolik. In the beginning, he didn’t work on the title character (he would get to that later). What Castelli pitched to Angela & Luciana Giussani, the sisters who created the series in 1962, was a backup strip that he would write and draw himself, titled Scheletrino (“Little Skeleton”).

In 1966, the teenaged Castelli launched Comics Club 104, often considered the first Italian comics fanzine. Though his resources were meager, Castelli sought to investigate the chronologies of many American comic strips. This was not without misadventure; unable to fill a gap in the chronology of the Mickey Mouse daily strip, Castelli invented a fictitious artist, Al Levin, and attributed the unknown strips to him.

In 1968, intending to bring the style of MAD magazine to Italy, Castelli and three friends founded a new comics magazine called Tilt, which unfortunately lasted only two issues. In 1969, he shifted his attention to the horror genre, and launched a magazine at Gino Sansoni Editore aptly titled Horror. He took this job seriously; alongside co-founder Pier Carpi, the next three years were spent building the credibility of a genre that was neither popular nor taken seriously in Italian comics at the time. Castelli found himself working in absolute freedom, which led to unusual experiments; a one-of-a-kind story from 1971 had its art made up of xeroxed 1,000 Lire bills, the lower-value banknotes of the old Italian currency.

In 1972, the Corriere dei Piccoli, a historic comics magazine established in 1908, changed its name to Corriere dei Ragazzi; Castelli became an editor at that magazine, and one of its most prolific writers. Before long, Castelli and artist Ferdinando Tacconi—an unsung hero of adventure comics, known abroad for his work on war stories for UK publishers like Fleetway—had created a series about a group of gentleman thieves, Gli Aristocratici (“The Aristocrats”). This feature was also translated into French and German, where it found notable success; it continued in Germany even after the conclusion of its first run in Italy. Castelli also wrote dozens of so-called “reality comics” for Corriere dei Ragazzi - short stories based on true events that might be considered a type of prototypical graphic journalism. He also revived Tilt, this time as a satire column drawn by the artists Bonvi (creator of the anti-war strip Sturmtruppen) and Daniele Fagarazzi. The three authors often appeared in the strip; an unusual and bold choice for the time.

It was also in 1972 that one of Castelli’s greatest and most beloved characters was created purely by chance. To fill a blank spot on one page in Corriere dei Ragazzi, Castelli came up with L’Omino Bufo (“The Funy Little Man,” with the typo). Written and drawn by Castelli, it was a gag strip whose humor relied upon dad jokes, bad puns and dubious wordplay. At the end of each strip there was always a little man who would laugh, saying “That’s Funy.” It is basically the first example of an Italian comic drawn 'badly' on purpose, which is a style that now enjoys great popularity, though at the time it was something readers had never seen before. As the writer Francesco Artibani once remarked, L’Omino Bufo’s humor was “based on jokes that everyone—even without admitting it—tells or has told, and to find them on paper is so liberating that it makes you feel less alone, and part of a community of anonymous idiots that reunite to laugh and shake their heads at the nonsense they have just read. L’Omino Bufo makes his readers feel better than the author, and this, if you think about it, is something that never happens.” The character soon became a mascot for the magazine.

In the second half of the 1970s, Castelli found himself busy working with Italian and foreign publishers, finding a home at Sergio Bonelli Editore writing stories for characters like Zagor and Mister No, as well as standalone works with his future Martin Mystère co-creator Giancarlo Alessandrini, and a young Milo Manara (The Snowman).

Between 1983 and 1984, while tending to Martin Mystère’s first stirrings, Castelli became editor-in-chief of the comics magazine Eureka, in tandem with his friend Guido "Silver" Silvestri (creator of the popular series Lupo Alberto). With help from a small circle of contributors, and on a really tight budget, the two were able to bring new life to the aging magazine, which featured the team’s own creations along with classic strips, as well as translated episodes of The Spirit by Will Eisner and The Shadow by Dennis O’Neil & Michael Kaluta. Issues #11-12 of the relaunched Eureka featured a story from Osamu Tezuka’s Black Jack - one of the first translations of a Japanese comic in Europe. Castelli introduced the story with a lengthy column in which mangaka such as Akira Toriyama, Leiji Matsumoto and Rumiko Takahashi were discussed for the first time in an Italian comics magazine, although anime was already huge in the country.

Another issue that is well-remembered today is #7, which included a pamphlet co-written by Castelli titled How to Become a Comic Artist, the first Italian-language professional guide to the trade. The small book lays out techniques and methods for writing a script and drawing a comic page, and gives advice on how to approach a publisher or pitch a story. In the days after Castelli’s death, several artists acknowledged on social media that this seminal guide was the spark that ignited their career in comics.

Along with his career as a comics creator, Castelli cultivated a profound knowledge of American syndicated comic strips, starting from when colleague and friend Carlo Chendi gave him a stack of old Sunday pages. In the decades that followed, Castelli would put together a significant collection of vintage material, weaving a web of contacts and trades with experts and scholars from all over the world. In 1996, he began to organize all of this material into an encyclopedic publication; the effort took him 10 years, compiling 1,800 data sheets for as many comic strips. Eccoci ancora qui! (“Here We Are Again!”) was published in 11 installments by If Edizioni between 2006 and 2008, and still represents the most accurate single study of American comic strips published between 1896 and 1916. Art Spiegelman once described it as “[a]n indispensable folly of loving scholarship,” but an English translation did not materialize.

By then, the creator of Martin Mystère had established himself as one of Italy’s most important comic historians. Over the years, he would edit several new editions of classic comic strips, and he wrote a huge number of essays. One later book that deserves special mention is 2010's Fumettisti d’invenzione (“Comics of Invention”), in which he describes how the role of the cartoonist has been portrayed in media throughout history.

With his widely entertaining and intelligent never-ending meta-narrative use of comics, almost every single one of Castelli’s creations, in particular the Detective of the Impossible, is a vehicle devoted to disseminating knowledge of comics' history and culture. Martin Mystère has always been peppered with graphic or textual quotes and hints, allusions to Carl Barks' "Lost in the Andes!", the Yellow Kid or the Italian strips of the fascist era, or to more exotic and varied comics of the past and the present. In one special issue, Martin Mystère was drawn on each page in different styles, from manga to funny animals to ligne claire to superheroes.

At a time when you couldn't make your discoveries via hyperlink or algorithm—we are not being nostalgic here, but rather stating the obvious and offering personal testimony—what Castelli did in comics that were distributed at every newsstand on the corner of every street, and in many other works beyond that, was something incredible; something that introduced countless readers, many of them very young, to a great body of knowledge. And most importantly for us, to a great knowledge of comics.

“Neither my first 17 years of life, nor the following 50 years, have any peculiarities that would make them worth being handed down to posterity,” wrote Alfredo Castelli in his 2015 memoir Castelli 50 - Il prequel! A humble statement, coming from a man who wrote the history of Italian comics.

The post Alfredo Castelli, 1947-2024 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment