Activist, author, and advocate Joyce Brabner passed away after a long battle with cancer on Aug. 1, 2024. Unsurprisingly to those who knew her, she documented that final journey in a series of thoughtful, poignant, and darkly comic Facebook posts entitled “Joyce vs. Cancer,” her way of relaying painful news to friends, family and colleagues.

”She taught me much and we laughed a lot,” said her partner Lee Batdorff, who broke the news through social media shortly after she passed. He and Joyce’s guardian daughter, Danielle Batone, gathered with Brabner’s close friends – Cindy Barber, Stephane Finley, Torella Trent, Toni Trent, Jacari Trent and Jasmine Cork – on Aug. 8 to light a seven-day candle in her memory.

Joyce Brabner was an avid reader from an early age, devouring comic books provided by her cousin. She was particularly drawn to Mad Magazine and its irreverent attitude toward authority figures and willingness to question cultural institutions. Supportive parents encouraged her need to speak truth to power, and she considered herself a full-fledged activist by her sophomore year of high school.

“I’ve been [an activist] since I was 15 and something made me so angry that I developed a voice and stood up and did something,” Brabner said in a 2016 interview with the online magazine Hyperallergic. "While we made it look kind of funny in the movies, I was pretty effective in working on feminist issues and with people in prison.”

“I wanted to do something for social change. You know, something for good. To put forward rather than take away. I wanted — and this was just too early for the punks — a purple mustache tattoo like the hairy Ainu, which would guarantee I would never be able to be employed as a sales clerk selling things I didn’t want,” she continued. “It later occurred to me that I could just not take those jobs. I would never have debt, because when you come from a poverty background that really can scare the shit out of you. I would, if I ever got that door open — this was important — I would hold the door open for as long as I could for anybody to come in behind me.”

Activism on its own didn’t pay the bills, and by the early 1980s, she found herself managing a prison arts program and operating Xanadu Comics and Collectibles in Wilmington, Del., as well running the local community theater that she had established, The Rondo Hatton Center for The Deforming Arts, named in honor of the iconic B-movie horror actor. The comic shop job was a natural progression from her growing involvement in fandom in the 1970s, and provided some much needed escapism to counter her work with prisoners, helping inmates find worth and purpose through theater and art. "Nobody cared about these folks," she said in a 2013 profile in Cleveland Magazine. "I wanted them to see themselves in ways they'd never imagined. Imagination can make success possible."

One of Brabner’s favorite comics during this time in her life was American Splendor, Harvey Pekar’s annual autobiographical comic magazine illustrated by a host of artists, primarily based in and around Pekar’s hometown of Cleveland hometown – an ongoing series of vignettes depicting the everyday life of Pekar, a curmudgeonly Veterans Administration Hospital file clerk, music critic and writer. When her business partner sold the last shelf copy of the 1982 issue of American Splendor before she was able to read it, Brabner wrote a fan letter to Pekar, explaining the situation and requesting a replacement. Impressed by her initiative, Pekar wrote back and included a copy of that missing issue, and they would continue to exchange letters for several months.

"Harvey fell in love with me because of the letters we wrote each other," Brabner told Cleveland Magazine. In 1983, Pekar invited Brabner to meet him in Cleveland, and after a single weekend together, they were engaged. "We had both been married before and we didn't expect perfect stuff," Brabner said. “I knew we were never going to agree on what movie to watch. But the big-picture stuff, we were in complete agreement on. I had a feeling he would be interesting his whole life."

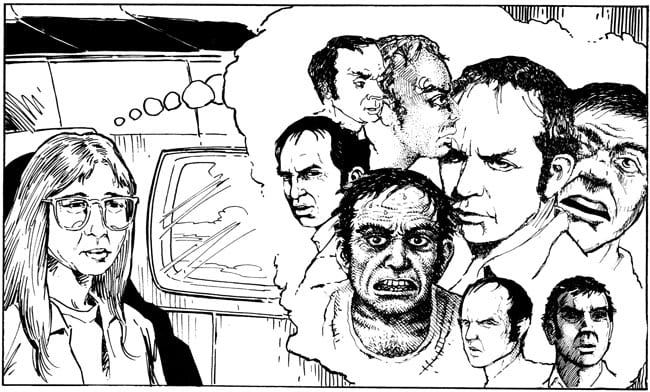

Like many of the people in Pekar’s life, Brabner became a character in American Splendor, and their marriage naturally became a part of the series’ ongoing narrative. “I drew Joyce quite frequently in American Splendor stories,” said artist Joe Zabel. “These depictions were more or less true to life and in line with the intent of Harvey’s scripts, but her character served the narrative function of providing an objective critique of Harvey's obsessive behavior. Hence, she was often depicted as being annoyed at Harvey and rolling her eyes.”

Brabner assumed the role of Pekar’s publicist, engaging in stunts like creating Harvey Pekar dolls – Cabbage Patch Kid-sized dolls featuring Harvey’s likeness and “just like the Shroud of Turin, they were made with clothing actually worn by the author, like some holy relic,” she recalled in a 1993 interview for Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with The Creators of the New Comics. “They were these odd collectibles, and I carried these ugly little dolls around at our first San Diego con together.”

The dolls garnered attention for Pekar’s self-published comic, gaining nine distributors for the book and making American Splendor profitable for the first time in its publication history. The increased visibility of the series helped Pekar to secure a deal with Doubleday to publish a collected edition of American Splendor. A series of guest spots on the popular NBC talk show Late Night with David Letterman followed in October 1986, culminating in one memorable, combative appearance in August 1988 in which Pekar argued with Letterman about antitrust laws and the ethical implications of General Electric’s purchase of the NBC broadcasting network. Pekar, who had been a regular guest during that two-year span, would not return to the Late Night stage until April 1993, during Letterman’s final months on NBC.

Brabner, meanwhile, realized that the marriage between art and activism could help her reach new audiences and embarked upon a career as a writer and editor of progressive nonfiction comics. In 1987, she assembled an all-star roster of comics talent to produce the 48-page one-shot Real War Stories, published by Eclipse on behalf of The Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (CCC0), a nonprofit military and draft counseling organization. The project was originated by Cleveland-based student activist Lou Ann Merkle, who sought Harvey Pekar’s advice on producing a conscientious objectors’ comic book, which led to Brabner’s involvement as editor.

As Merkle wrote in 1987, “We created this comic book to give you a chance to hear for yourselves how war and the military affect the people who’ve been there.” Contributors included prominent British creators Alan Moore and Brian Bolland, major American creators including Bill Sienkiewicz, Stephen Bissette and Steve Leialoha, and military veteran comic book writers Denny O’Neil and Mike Barr. Real War Stories sought to “produce a volume that would tell the stories of Vietnam veterans who'd been traumatized by their war experiences, enlisted personnel in the services who'd successfully sought CO status, and civilians victimized by US-funded Central American dictatorships,” according to the CCC0.

“I'd occasionally met Joyce and Harvey Pekar at comics conventions, but I really got to know Joyce through working with and for Joyce on the Real War Stories project,” said Stephen Bissette. “It was a loaded project, to say the least. I'm glad I got to work with Alan Moore, John Totleben, and Joyce on it, however brief our respective contributions. She was one of the most assertive, professional, and straightforward editors I'd ever worked with: in the first conversation, she laid out what the project was, what she needed, what she expected, when she expected it done, and provided everything that was necessary to completion of the work, except for the paper and art tools.”

Real War Stories drew negative attention from both the Department of Defense and the Department of Justice, who publicly questioned the veracity of the autobiographical accounts depicted in its pages. Brabner stood by her sources and had carefully documented all of her interviews for Real War Stories, and with military Naval court records supporting those accounts as well, the Department of Defense ultimately withdrew their official objection to the comic book.

“Joyce was 'no bullshit,' ever,” said Bissette. “Remember, she took on the fucking U.S. government and military in a courtroom, and won. Confrontational without being mean-spirited, strong without being abusive, by my experience, anyway. She spoke her mind, without flinching, and expected the same from you; that candor might seem unkind to some, but I always appreciated it."

“When I was coming out of a particularly difficult period in my personal life in the 1990s, and others closer to me personally were pussyfooting around the pain, Joyce referred to me as ‘damaged goods,’ which was absolutely accurate,” Bissette continued. “The assessment helped me work to better myself. It was a kindness, what I needed, and Joyce was the one willing to provide it.”

Brabner took on the entire United States government with her follow-up project Brought to Light, a documentary comic book produced at the behest of the Christic Institute, a public-interest legal firm, best known at that time for its work on the Karen Silkwood nuclear safety regulations case. Brought to Light was serialized by Eclipse Comics in 1988 and packaged in a collected edition the following year. The two-in-one “topsy-turvy” collection featured Brabner and artist Tom Yeates’s journalistic account of the CIA’s attempt to assassinate independent Nicaraguan contra leader Eden Pastora in a bombing at La Penca and a second story, Shadowplay, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Bill Sienkiewicz. Publishers Weekly described the long out-of-print Shadowplay as “a masterly satiric expose of ‘The Secret Team’ that came to direct the Reagan administration's covert war in Nicaragua; a scathing black comedy documenting the CIA's long history as a criminal shadow government.”

Brabner’s inspiration for Brought to Light came from a constitutional lawyer and activist, who was on the lecture circuit educating the public on the activities and methods of the Central Intelligence Agency. “I watched the way he was dealing with audiences, and I saw that there are two ways to appeal to people,” Brabner told Hyperallergic in 2016. “One was this whole conspiracy, all these evil people, which is the side that Alan took. The other was the down-to-earth story of these two journalists who were trying to find out how they got hurt. I took that.”

Brought to Light received positive coverage from mainstream outlets including Mother Jones, Interview, and Vanity Fair, and further established Brabner as one of the major voices in the nascent field of political comic book journalism. “Joyce was a great political activist who involved me in important projects such as Brought to Light and Real War Stories, for which I remain forever grateful,” said Alan Moore. “She was also a good friend, along with Harvey and Danielle, and I shall miss her enormously.”

Brabner edited a second installment of Real War Stories in 1991, but by the time that book saw print, Pekar had been diagnosed with lymphoma and had to undergo aggressive chemotherapy. Brabner encouraged Pekar to document his treatment in comic book form, as he had documented his life in the pages of American Splendor. As the scope of the project grew, Brabner made the decision to co-write the story with Pekar, and American Splendor artist Frank Stack, then on sabbatical from his professorship at the University of Missouri, signed on to illustrate. Unlike Pekar’s typical comics, this would be a single, longform narrative, published complete in the graphic novel format.

Their joint autobiographical story, Our Cancer Year, depicted Pekar’s diagnosis and treatment in great detail, and also followed his and Brabner’s everyday life during that year, as Pekar went on medical leave from his job at the V.A. Hospital, the couple bought a home, and then became legal guardians to a daughter, Danielle, who found a loving and caring home with the Cleveland couple. Our Cancer Year was published to great acclaim by Four Walls Eight Windows in 1994, and would win the Harvey Award for Best Original Graphic Novel the following year.

“When you read the book without knowing who Harvey or Joyce are, you can see that it really is by Joyce Brabner with Harvey,” Brabner told Hyperallergic in 2016. “But the joke we had was: it’s Harvey’s cancer. Harvey had to shake and bake, and I helped. The truth is he didn’t really remember a whole lot of stuff in order to write about it. He was terribly ill. We were trying to escape from a nightmare, but we’re there mining our misery for dramatic purpose.”

Misery enjoys company, however, and readers and creators connected with their memoir on a personal level. “Our Cancer Year was a seminal work of graphic medicine, a growing field of medical humanities combining comics and healthcare, before there really was such a thing,” says Brian Fies, whose autobiographical account of his mother’s illness, Mom’s Cancer, was serialized online in 2004 and published in a collected edition in 2006. “Along with a few other graphic novels such as Justin Green’s Binky Brown, it was a prototype for an outpouring of deeply personal, acutely revealing nonfiction comics centered on their authors’ experiences with illness and treatment. Graphic medicine is now taught in medical schools and discussed in academic conferences around the world, and Our Cancer Year was the soil in which it took root."

“I met Joyce at the 2012 Graphic Medicine Conference in Toronto, which I’d helped organize,” Fies continued. “Being recognized as the pioneer that she was made her happy and proud, but not particularly surprised, I thought. She knew Our Cancer Year was good, and she enjoyed seeing doctors, nurses, and university professors finally catching up. We connected over both of us writing comics about our loved ones surviving cancer, which is an especially tiny subset of graphic medicine, and kept in touch over the years.”

Pekar was in remission and his health had improved considerably by the time Our Cancer Year was published, and he and Brabner toured the country signing at bookstores and comic shops, introducing them to the larger comics community beyond Northeast Ohio. “When I first spoke to Harvey about illustrating American Splendor, it was right around the time they were promoting Our Cancer Year, and they had plans to come to Chicago, where I was living at the time,” said cartoonist Josh Neufeld. “So even though I had never met either of them in person, Harvey put Joyce on the phone to discuss the possibility of them staying with me and my then-girlfriend–now wife–at our grungy little Wicker Park apartment! An intimidating prospect for two kids in their early twenties! In the end I think they found more suitable accommodations, but by then I was part of the ‘Pekar-and-Brabner-verse.’"

“While it took awhile for Harvey to give me work, Joyce and I collaborated extensively in those first few years. First on a 12-page ‘follow-up’ to Our Cancer Year, ‘Be Careful Not to Pull too Hard on Loose Ends,’ published in American Splendor, and a four-page comic about Typhoid Mary that was originally part of the program for a play Joyce was involved with. I remember Joyce as being very easy to work with — she instilled in me the idea of thinking of each panel in a comic being a ‘theatrical beat’ —something she’d internalized from her previous experience in community theatre. This was a concept I found very useful in my own early comics writing. She was also very patient with my youthful foibles.”

The success of Our Cancer Year led to renewed interest in the prospect of adapting American Splendor as a major motion picture, something that Pekar and Brabner had pursued intermittently over the previous decade. Playwright and director Vince Waldron had successfully adapted American Splendor as a stage play, including a production starring Dan Castellaneta. But it was Our Cancer Year that ultimately set the stage for a big screen adaptation.

“Harvey and Joyce had been trying to get it made for years, in various ways, before we were involved,” said Shari Springer Berman, who wrote the screenplay and directed the movie American Splendor with her husband Robert Pulcini. “Ted Hope was a huge American Splendor fan, and he wanted to get this movie made. He had a production company called Good Machine, and they were one of the great New York-based independent film companies, really fearless with the kinds of movies they made. Ted had seen some of our work, and maybe because we worked as a couple, he thought of us.

“I was shopping for food with Bob and got a call on my cell phone, and there was a message from Ted saying, ‘I’ve got a project that’s very near and dear to my heart, and I want you to say that you’re willing to do it, even if we have to do it for a hundred thousand dollars.’ He said it was American Splendor and that he wanted us to do it. I’d heard of Harvey through Letterman, but wasn’t up on it. But he said he was going to send us some stuff, so he sent me a big box of American Splendor comics and a VHS of Harvey on the Letterman show. And I thought, where do I even begin with this? But I got more and more intrigued, then obsessed. And we said we’d do it.”

Before the couple could officially sign onto the production, they had to meet with Pekar and Brabner to get their stamp of approval. “We met at Harvey and Joyce’s favorite restaurant, in Cleveland Heights, and he and Joyce immediately got into an argument, right in front of us,” Springer Berman continued. “Bob and I couldn’t stop laughing, because we got this. We thought, ‘We get you guys.’ They approved of us, and we approved of them. Then we went on this wild adventure together.”

Over the course of the following year, Berman and Pulcini wrote and directed American Splendor, overseeing a production shot on location in Cleveland that starred Paul Giamatti as Pekar and Hope Davis as Brabner, with the real-life Pekar and Brabner appearing as themselves. The biopic utilized documentary footage, professional actors and animation to adapt American Splendor and Our Cancer Year, proving Pekar’s adage, "Ordinary life is pretty complex stuff."

"They were exactly in character on set,” said Springer Berman. “We had a fantastic set by our production designer, Thérèse DePrez, she recreated Harvey’s house, and it was totally accurate. Joyce gave us his old records to put on the set, and when they got there, he took one of these records, sat down on the couch, played it, and fell asleep. Joyce told us to please take more of his records, because she could never get him to throw anything out. Then he sat up and yelled, ‘Joyce! Why are you giving away my records?’ Completely in character. It helped Paul Giamatti and Hope Davis, who were playing Harvey and Joyce, whenever they were on the set. That was great, and it was always fun when they visited. Didn’t change at all. They were who they were, take it or leave it.”

Those down to earth qualities endeared them to everyone on the set, according to stars Hope Davis and Paul Giamatti. “I remember hanging around with Joyce at the Cannes Film Festival when American Splendor played there,” said Davis. “She was a woman who cut her own bangs. She was a total non-conformist. She said, ‘I keep looking around and thinking where the hell am I??’ She didn’t believe the hype. ‘Is it money in the bank?’ she’d say.”

Giamatti echoed that assessment. “I don’t have stories I’d want to share but I will say Joyce had the most surprising silvery, bubbly youthful laugh when she chose to let it loose. She was funny, weird, tough, sweet, wicked smart, she had limitless curiosity and limitless heart and soul and she was a great friend. I’m gonna miss her very much. It was an honor to know her. Her and her nutty husband.”

The movie was just one part of Springer Berman and Pulcini’s journey with Pekar and Brabner, as they spent the better part of a year traveling together and attending film festivals, screenings, and the occasional comic book convention. “Right before American Splendor went to Sundance, Harvey went through a serious bout of depression, and we didn’t think it was going to happen, and we thought that was too bad,” said Springer Berman. “But Joyce said, ‘Don’t worry, he’ll be there. I’ll make him well,’ And she did. Harvey got a standing ovation at Sundance, he stood up, he shook hands, and she just turned him around from being so deeply depressed to being amazing and having the time of his life. She was a great caretaker to Danielle, and just adored her, and loved her. And she took care of a lot of people.”

The film earned many accolades, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay, earning Movie of the Year honors from the American Film Institute Awards, the FIPRESCI Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and The Grand Jury Prize Dramatic at the Sundance Film Festival, and dozens of other awards and nominations. But apart from an increased sense of financial stability, Pekar never felt like a celebrity – and Brabner was there every step of the way to keep him sane and grounded.

“I loved Joyce, and we were friends,” Springer Berman said. “We kept in touch all these years, even after Harvey died. She’s one of those people who was honest to a fault. She was so funny, so sharp-witted, and really quite brilliant. She was an acquired taste, but I totally adored her. She was a wonderful caretaker. I don’t know how she put up with Harvey’s insanity, but she did, and she loved him, and he loved her.”

Renewed interest in American Splendor brought Our Cancer Year and several of Pekar’s older collections back into print, along with a new, movie-branded American Splendor collection featuring movie poster artwork depicting Paul Giamatti as Pekar on the front cover. Dark Horse Comics had published American Splendor and several spinoff miniseries from 1993-2002, but Pekar brought the title to DC Comics imprint Vertigo in 2005 beginning with an “origin story” graphic novel called The Quitter, illustrated by Dean Haspiel.

“I helped get DC Comics to publish the last eight issues of American Splendor,” Haspiel said. “I have many memories of Joyce Brabner but the one I wanna share now is the time I was talking to Harvey on the phone during his time at Vertigo. Sometimes he would dictate scripts for me to draw. Other times it was to catch up and run ideas by me. This one time, I was talking to Harvey and he would giggle or yipe intermittently. I couldn't make heads or tails of it. When I finally asked him, ‘What’s so funny?’, he admitted to me that Joyce was clipping his toenails and it was making him laugh. Talk about high romance!

“I couldn't erase that image from my mind if you paid me a million bucks. I loved the idea of Harvey conducting business on the phone while Joyce was grooming him so much that I paid homage to it in one of my collaborations with Harvey. He's on the phone clipping his toenail but I knew it was really Joyce doing the clipping.”

Pekar’s cancer returned a second time, then a third. Prior to undergoing treatment, he passed away in July 2010 following an accidental overdose of the antidepressants fluoxetine and bupropion as he adjusted to his new regiment of prescriptions. Brabner, who had taken advantage of her higher profile to further her activism, now had an additional cause to champion, the preservation and protection of Harvey Pekar’s legacy. She spearheaded the effort to build a desktop statue dedicated to Pekar at the Cleveland Heights-University Heights Library, where he spent many hours reading and where he wrote many of his American Splendor comics. At the dedication ceremony in 2012, Brabner noted in an emotional speech that Pekar always felt safe and inspired there, and believed that a library card was much more important than a credit card.

In July 2015, the northwest corner of Coventry Road and Euclid Heights Boulevard was renamed Harvey Pekar Park in his honor. His gravesite at Lake View Cemetery is frequently covered in ballpoint pens left in tribute by friends and admirers. All of which comes back to Joyce Brabner. “She was a fierce defender of Harvey’s legacy, to make sure that he would not be forgotten. She was a force,” said Springer Berman. “All of those memorials to Harvey came because she pushed for them.”

Apart from her efforts on behalf of Harvey Pekar, Brabner chose to focus her creative and editorial talents over the past decade to projects on a global scale rather than the local comics scene, according to Cleveland cartoonist Derf Backderf.

“Joyce wasn’t much involved in the Cleveland comics community, or the Ohio one for that matter. Harvey was, in that he hired local artists and was out and about promoting his books. She kept a lower profile,” he said. “We lived in the same neighborhood in the 1980s and ‘90s, the peak Splendor period. I ran into them regularly, at the grocery store or post office, or in the newsroom of the altweekly paper. Harvey wrote jazz reviews, and the occasional cover story. I was the cartoonist. But I never worked with either of them. I never got the impression Harvey liked my work, but Joyce later told me he did. I never got more than a grunt out of him. He wasn’t much for small talk. Joyce, on the other hand, would talk to me for an hour!”

Keith Knight, another veteran of the alt-weekly papers, agreed. “What I loved about Joyce was that no matter how long it was that I hadn't talked with her, the moment I got on the phone with her, it felt like we'd been chatting every day for the past several months,” Knight said. “She–and Harvey!–made me feel like I was a true part of the indie comics community.”

Brabner continued to write, too, and in 2014 she and artist Mark Zingarelli collaborated on the graphic novel Second Avenue Caper: When Goodfellas, Divas, and Dealers Plotted Against the Plague, the story of how a group of artists and activists in New York City attempted to fight AIDS in the early years of the epidemic. Their book won the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Best LGBT Graphic Novel, as its depiction of the AIDS crisis and the New York community that banded together to bring pharmaceuticals across the border from Mexico for distribution among those afflicted with AIDS.

The comics community came right to Brabner’s doorstep in 2016, as the Republican National Convention with the Presidential ticket of Donald Trump and Michael Pence was held from July 18-21 at the Quicken Loans Arena. She seized upon the opportunity to mobilize an international group of cartoonists to document the event in real time, on a YouTube “Comixcast,” a comics journalism event with artists including Gerta Oparaku, Junco Canche, Katie Fricas, Tim Fielder, Ted Rall, Paul Mavrides, Tony Puryear, Vishavjit Singh, Seth Tobacman and Mark Zingarelli. "Joyce called me in the first half of 2016 to be part of a 'Cartoonists Against Trump' trip to the RNC in Cleveland which was her home city,” said Vishavhit Singh. “I was honored to be invited as part of a group of 14 very eclectic and diverse illustrators and cartoonists.

“Joyce took care of our housing and transportation needs. She was like a grandmotherly sage guiding us to be ourselves and capture what we observed and felt at the carnival that political conventions are. I decided to channel my Captain America persona during the convention and had one of the most strange and unexpected outings as Captain America. Joyce's brave and creative spirit will be with me forever as a parting gift from her."

William Byron, an artist and activist based in Brabner’s native Delaware, also found her to be incredibly generous when it came to guiding the next generation of political activists. “I can tell you that Joyce was hugely helpful with giving me advice and direction towards a lot of my activist work, as I imagine she was with anyone,” he said. “She was essentially a great traffic director in times of chaos and I think her ultra competence and tunnel vision made lazier people misunderstand her. Really, Joyce was a person who simply got things DONE. I've never had any other individual as astute and forward thinking as she was, and she gleaned everything I was going through just from an email.

“I'm a big fan of Harvey's too and they made such a perfect couple together but I did feel her own output sometimes got ignored by people who viewed her simply as 'Joyce from American Splendor' but I never heard or saw her make any serious comment about that and that's just my own conjecture. Again, just her patience and articulation with guidance and direction–never stern and distant but commanding in a really benign, inspirational way–a rare balance from a person of rare qualities.”

And those qualities are what drove Brabner to activism, and to offer help to whomever she could, however she could. “Yeah, I value comics. Maybe it’s a family tradition,” she said to Hyperallergic in 2016. “You can do anything with words and pictures. That’s the motto in our house — that and what I put on Harvey’s tombstone: ‘Life is about women, work, and being creative.’ Life is about love, work, and making art.”

Memories of Joyce by Danielle Batone

Joyce had a knack for making everything fun. When we came into each other’s lives, there was an instant spark of understanding. Behold! An adult who truly understood me, a weirdo kid who always had to have her hands in some type of art supplies. Joyce was the first adult in my life who didn’t pound that whole “look, don’t touch” attitude on me.

This woman had a living room full of art supplies, glittery sequin treasures in fancy jars that I knew were once bottles of Orangina and the fancy blue glass-bottled Clearly Canadian, but she was the first adult I’d ever seen who recycled these items as stash bottles for tiny odds and ends.

Joyce always encouraged me to exercise my imagination and to never, ever lose that. She made boring things fun, always setting tiny goals and little scavenger hunt-type things to break up the mundanity. There was a whimsical air about her, most particularly her voice. It was so youthful back when I met her, of course, but even to the last time I spoke to her on the phone.

We talked a lot – because Joyce talked. Anyone who knew her knew that a ten-minute conversation would turn into an hour and a half before you knew it.

There are a lot of things I could go into detail about, but there’s one thing that’s always been with me, and it was a phrase that we began saying to each other back when I was still a shrimp with stringy, long golden hair.

It was on a trip to Texas and Joyce had found out that some random guy got a DUI/OVI for driving his car erratically with his pet iguana at the wheel, like some tiny Dragon Captain. This guy gets pulled over and is clearly drunk. Joyce told me that when the police asked him why an iguana was on the steering wheel, the guy explained that the iguana was driving. The police were processing this information when the guy followed up with, “well, he’s a very smart iguana.” From there on out, Joyce and I used this as an inside joke.

Though as a kid, I’d imagined said iguana would be this godly creature with a feather headdress and tiny little scepter encrusted with flat black rhinestones kind of like the one from Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain.

My point, though, is that Joyce and I bonded at first sight. We recognized parts of ourselves in each other and I could not be more grateful that she was such a huge part of my life. She made an effort to find things for us to do together and is hugely responsible for encouraging me to try all different forms of art, from theater to sculpture. I miss her very much and I believe she touched the lives of everyone she met by taking a genuine interest and care for the people she recognized as ‘tribe.’

I know she’s directing A Very Smart Iguana: The Musical in the afterlife. I will always honor her and her memory.

The post Joyce Brabner, 1952-2024 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment