“It is never easy to demand the most from ourselves, from our lives, from our work…. But giving in to the fear of feeling and working to capacity is a luxury only the unintentional can afford, and the unintentional are those who do not wish to guide their own destinies.” -Audre Lorde, The Uses of the Erotic

‘Experimental’ is a term that is often maligned. When you describe a book to someone as ‘experimental’ you should be prepared for them to never read it. The term, rather unjustly, connotes a work that is confusing, boring, opaque, or, worst of all, pretentious. Tara Booth’s newest memoir Processing: 100 Comics That Got Me Through It (Drawn and Quarterly, 2024) is experimental, but it is also hilarious, unflinching, and accessible. Processing is Booth's latest contribution in a bibliography of several books and countless zines, including the Ignatz Award winning How to Be Alive (Retrofit Comics, 2017), and Nocturne (2dcloud, 2018).

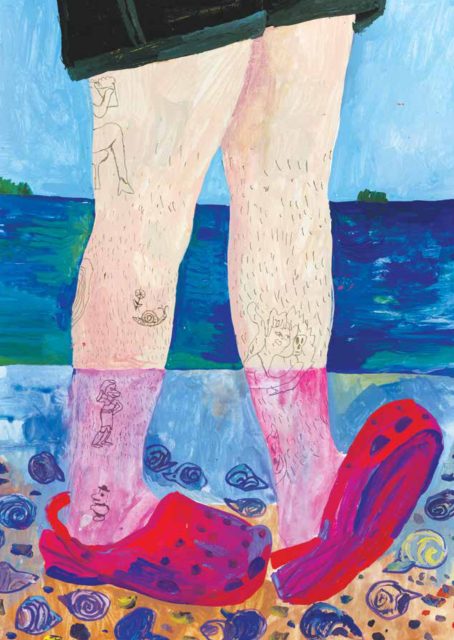

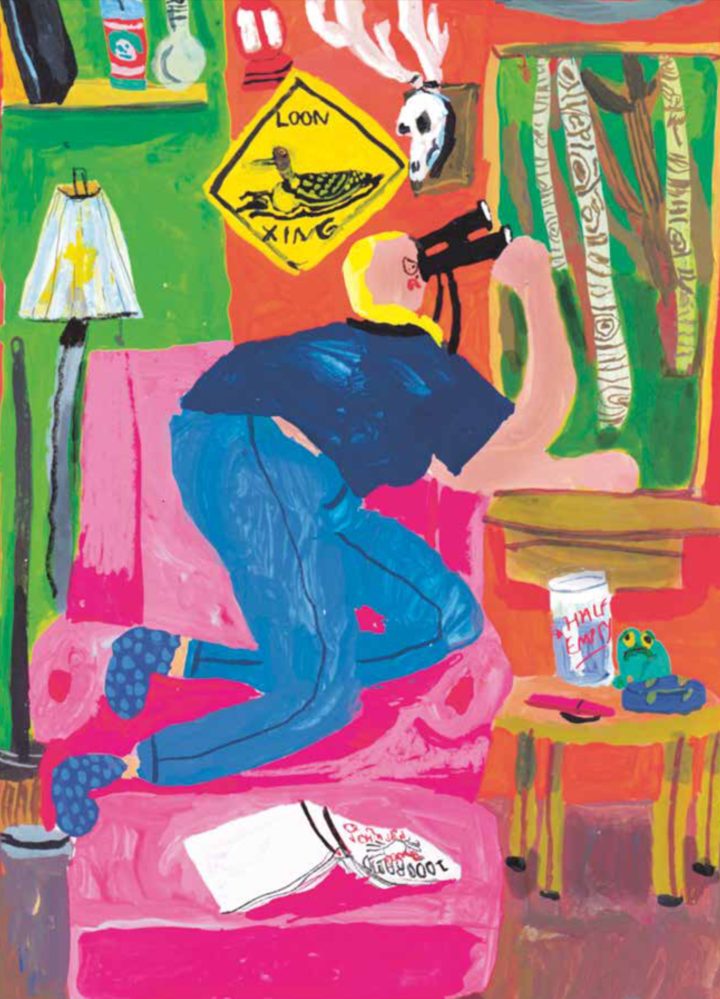

I’ve been following Booth for a while, struggling to find a vocabulary to fully encompass her unique art. Booth’s work exists across so many genre boundaries that when the right formal comparison struck me, it was fitting that it was something equally eclectic: Booth’s work is a story quilt. Her layouts mostly consist of large scenes taking up a whole page. They’re emotionally revealing tableaus rather than filmic snapshots of action. Much like a good story quilt, Processing uses simple figures and colorful, patterned backgrounds to make its complex emotional storytelling and experimental layouts approachable and enticing. Her work’s childlike sense of play suggests an up front honesty reminiscent of sequential story quilts by Faith Ringold, whose pieces, like Booth’s comics, make immensely serious topics immediately accessible.

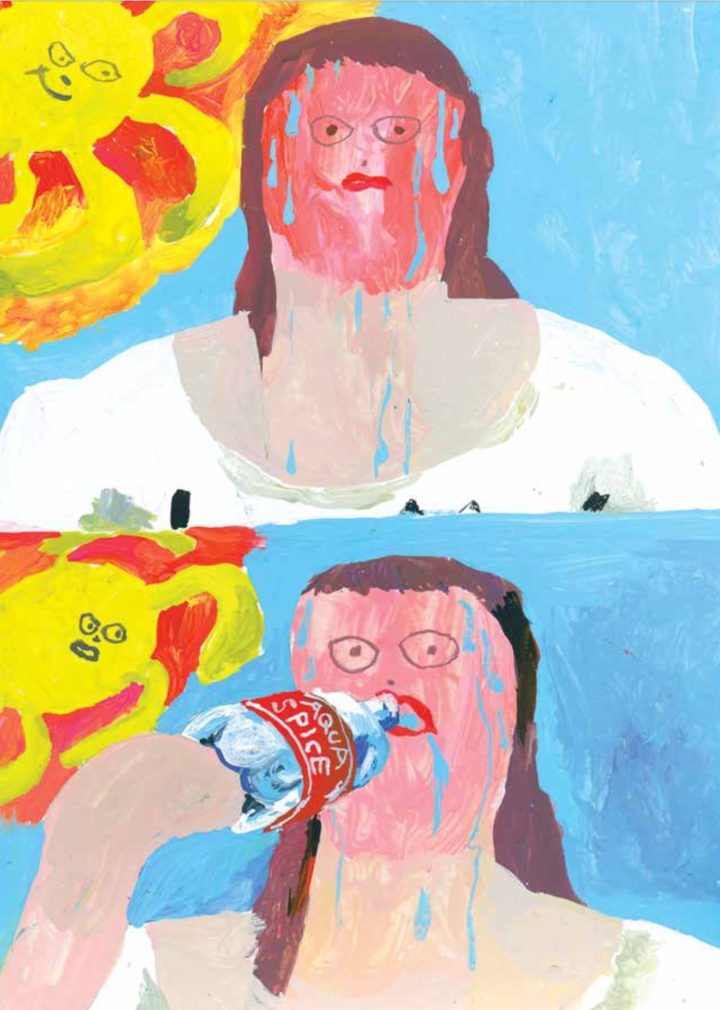

This creates a comic unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Booth’s paintings are mostly gouache and intensely colorful without being overwhelming. Her depictions of herself are liable to change from panel to panel with a freedom akin to Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s dynamic, loose style of self-portraiture. These elements come together to create a work which is both incredibly entertaining, yet also formally challenging and wholly original.

This creates a comic unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Booth’s paintings are mostly gouache and intensely colorful without being overwhelming. Her depictions of herself are liable to change from panel to panel with a freedom akin to Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s dynamic, loose style of self-portraiture. These elements come together to create a work which is both incredibly entertaining, yet also formally challenging and wholly original.

While Processing’s title states that it consists of one hundred comics, it’s hard not to read the book as one continuous work, more like a novel than a story collection. Individual comics are rarely titled, and, because of Booth’s willingness to take up a whole page with one huge beautiful panel, the convention of the gutter, which we so often take for granted, is almost entirely foregone. One series of comics begins with Booth reading a Ram Dass quote about people who appreciate every tree in the forest, but then can’t do the same with people. Booth examines trees outside her window with binoculars until she finds a tree with an evil face and the words “Disgusting tree that makes everything smell like cum,” written beneath it. Booth looks the reader in the eye and says “Some trees definitely just suck,” before we move on to a comic about not being an asshole and invariably ending up an asshole, until we end on jumping to Booth’s sense of unfulfillment and depression surrounding dating. Each comic is fluidly thematically connected to the next because they’re all such direct depictions of Booth’s interiority. Booth creates such a complete sense of self for the reader that the connections between one comic and the next become as intuitive to the reader as they are to Booth.

One of the great strengths of comics memoirs lies in their ability to depict serious, often horrifying experiences, in a way that communicates their subjectivity while preserving the memoirist’s mandate to write “the truth.” This relationship between the emotional truth of an experience and the intellectualization of the writer’s telling of it is often found between a comics’ drawings(the subjective) and its captions(the intellectual, if not objective). Booth plays with this relationship masterfully. Processing works through a lot of Booth’s deepest struggles from alcohol abuse to binge eating to depression, but she’s able to convey the absurd, even comical aspects of these experiences in tandem with their sadness and trauma.

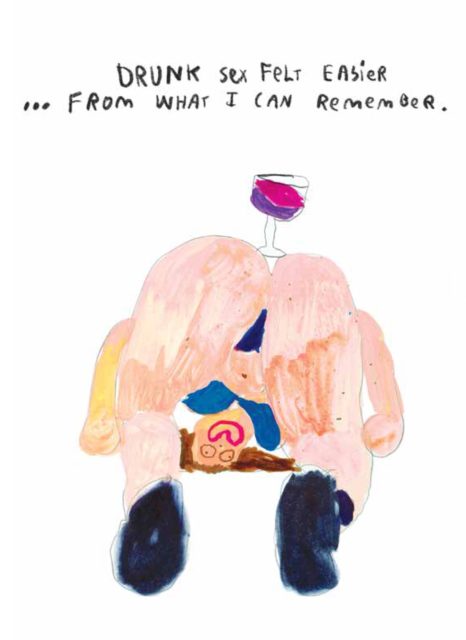

In one comic about how alcohol became destructively tied to her sex life, she says “Sex is weird. Sobriety & sex can be difficult for a lot of reasons—Especially from a trauma perspective. Drunk sex felt easier…From what I can remember.” The text is quietly heavy and thoughtful, its ellipsis laden with the terrified lacunae of someone who’s had far too many black outs. But the painting beneath the caption is playful. In it, Booth stares at the reader through her spread legs in a naked downward dog position, a glass of wine precariously perched between her butt cheeks. In a comic about binge eating, an anthropomorphic piece of cereal in cowboy books and a hat whispers at Booth to “Finish me,” before she pours bowl after bowl of cereal into her mouth. They’re cartoony and weird with an underlying unease and sadness. Memoir relies on creating a compelling relationship between the feeling of an experience in the moment with all of the insight and anxiety of writing about it. Knowing this, Booth takes advantage of comics’ unique ability to present both states at the same time resulting in a vital, dynamic memoir.

In one comic about how alcohol became destructively tied to her sex life, she says “Sex is weird. Sobriety & sex can be difficult for a lot of reasons—Especially from a trauma perspective. Drunk sex felt easier…From what I can remember.” The text is quietly heavy and thoughtful, its ellipsis laden with the terrified lacunae of someone who’s had far too many black outs. But the painting beneath the caption is playful. In it, Booth stares at the reader through her spread legs in a naked downward dog position, a glass of wine precariously perched between her butt cheeks. In a comic about binge eating, an anthropomorphic piece of cereal in cowboy books and a hat whispers at Booth to “Finish me,” before she pours bowl after bowl of cereal into her mouth. They’re cartoony and weird with an underlying unease and sadness. Memoir relies on creating a compelling relationship between the feeling of an experience in the moment with all of the insight and anxiety of writing about it. Knowing this, Booth takes advantage of comics’ unique ability to present both states at the same time resulting in a vital, dynamic memoir.

It’s easy for memoirists to slip into a retrospective tone, ignoring that, by virtue of being alive, there’s still a life ahead of them. Booth’s reminiscences on her life stand out because they’re coming from a living present. Booth is still an active participant in her own health, and her own difficulties. As the tense of the title suggests, Processing is a composition of the past in direct, unavoidable conversation with the present. One of the last observations in Processing is: “Healing is a slow thing. It doesn’t speed up just because you’ve got things you want to do or joy you want to feel. It keeps plodding on in its own time. Relative, maybe to how long you spent feeling small or bad, or wrong. Healing doesn’t happen any quicker just because I’ve learned enough to recognize why I feel the way I do.” Booth finishes on an optimistic, but realistic note, acknowledging her increasing ability to heal, but also her continuing capacity to be hurt and hurt in turn.

The post Processing: 100 Comics That Got Me Through It appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment