March 29th saw the end of an era as Phoebe and Her Unicorn ceased daily publication in newspapers- although the light fantasy daily comic will live on in middle grade graphic novels. The close of this ten year publication is but one arc in the career of Dana Simpson, though. Dana Simpson got her start in 1998 with the first generation webcomic Ozy and Millie, which distinguished itself from peers through its relative normalcy, with a tone far closer to Calvin and Hobbes than Penny Arcade, depicting the day-by-day adventures of furry elementary school students. As Dana Simpson embarks on a new phase of her career, she was gracious enough to agree to another interview with The Comics Journal. Previously, she had been interviewed by Alex Dueben in these pages in 2018.

-William Schwartz

WILLIAM SCHWARTZ: Thank you for agreeing to this interview, Dana.

DANA SIMPSON: You’re welcome, and thank you very much for giving me a chance to talk, something I enjoy! Has it really been seven years, since that last interview? No wonder I feel like I have so much to say. So let’s go!

I'd like for you to discuss a bit how you made Ozy and Millie. As in, physically, what was involved with setting up your own web domain and posting it on the Internet? Did anyone help you, or offer encouragement for the endeavor?

Man, early webcomics were The Wild West compared to now. I mean, it was a different era for the internet. You really had to know what you were doing, in a way no one does now.

And I didn’t, particularly, but I had learned basic html in a college class, and that was enough. In the very beginning I had to write all my own html, and change it manually every time I updated the strip. No part of it was automated, because I had no idea how to do that.

Back then, too, everybody had slow internet connections. Dial-up was still really common. And everybody had big heavy CRT monitors, with screen resolutions of 640 by 480. So the standard size people would upload webcomics was 600 pixels wide.

You really can’t read much of anything at that size, or see much of anything, unless the letters are really big, and the artwork is really simple. I think it affected the style of early webcomics, in kind of a similar way to how the limitations of newsprint affected the style of newspaper comics.

I hated being limited by that size, so being a dangerous, freethinking rebel, I uploaded mine at 700 pixels wide. People actually complained to me about the tiny amount of side scrolling that forced them to do. It’s funny how no one ever seemed to mind scrolling vertically, but make people scroll horizontally even a little and you get email.

Those strips look tiny on my Retina 5k monitor now. I have to zoom in just to see them. They’re like long narrow postage stamps. I’m happy I also saved all that stuff at high resolution (known today as normal resolution).

Also? Because everyone’s connections were so unbelievably slow, even the tiniest image files took time to load. So a friend advised me to save them as progressive gifs, rather than…whatever the other kind was. So they’d unblur all together, rather than loading from the top down. Because at that speed, all the dialogue would load before any of the art did. And that’s no good.

I was a communication/journalism major. So this was all stuff I had to learn on the go. It was totally different from how any of it works now.

I also didn’t have my own domain name at first. A lot of people didn’t! The original URL for Ozy and Millie was just a username URL on the web space my college assigned me. When a friend who was more technical than I was showed me how to set up a dedicated URL and point it at my comic, I felt suddenly much more professional.

I didn’t have scripts to do things like update the site automatically until I got on Keenspot, in 2001. That felt pretty cool. Suddenly I could upload my strips to a server and the site would update accordingly! I loved that. It’s half of why I was even on Keenspot—they had scripts! They were run by people who actually knew what they were doing! Kind of! Way more than I did.

Shoutout to Bill Holbrook, creator of the legendary online strip Kevin and Kell—started in 1995 and is somehow still going—and the syndicated strips On the Fastrack and Safe Havens. Bill noticed me early, encouraged me, and helped me grow my audience.

He was one of the only webcomics artists who was doing kind of the same thing as me—newspaper style strip, on the Internet. Kevin and Kell was maybe the first online strip I read, so he was part of why I knew it was something you could do. And having him out there encouraging people to read me was part of how I first acquired an audience of any size. I owe Bill a lot. I still see him at comics stuff sometimes, and he’s just a super nice person. He says now “I always knew you were going places.” He helped that be true.

What sort of reception were you expecting, and what sort of reception did you receive in regard to Ozy and Millie? Did the webcomic model ever seem sustainable to you, or did you come to see your art purely in terms of your own expression, rather than how it was received?

My goal with Ozy and Millie was syndication, a goal I obviously did not achieve with that strip. I didn’t really want to be a web cartoonist. Not because I thought there was anything bad about it—being indie has its perks—but because I wanted to make a living off my work, and nobody really knew how to do that with webcomics in those days. We didn’t have Kickstarter, or Patreon, or anything like that, so we were all poor, and I wanted to be less poor. Also, I dunno, I was more interested in traditional comics than in what webcomics were like at the time—a lot of them were about gaming, or tech stuff, or anime, and those weren’t really my interests.

But I couldn’t seem to get syndicates’ attention, and people online seemed to like what I was doing, so I became a web cartoonist and stayed one for more than a decade. And other than rarely having money, I did love that experience.

I dunno what reaction I expected from people online. I mean, in the beginning, I was 19 years old, and delusional enough to think syndication might happen any day, so what I initially wanted from the webcomics experience was feedback, so I could get better, and increase my chances of syndication. And I did actually get that, I suppose, in the long run.

In the shorter run, I found myself with a dedicated audience, some of whom really liked what I was doing. Turned out there was an audience for what I was doing. Cute, furry, childhood-focused, sardonic, hopefully sometimes insightful, like if you mixed up Calvin and Hobbes, Peanuts, Pogo, and Bloom County (four strips that had made me want to make comic strips in the first place) in a large pot. At least that’s what I was going for. And even in the beginning, there were always at least a few people who read it and told me it was their favorite thing now.

It was a comic about kids who were different, unsatisfied with the world and their place in it, struggling against the stifling conformity of kid society and the adult authority figures who enforce it, and a lot of people seemed to connect with that.

And that was a good enough reason to keep at it, so even when I had to admit syndication might not be just around the corner, I had other reasons to keep going. I had an audience that was connecting with what I was doing. That felt amazing. It still does.

The way my spouse put it at the time was “Ozy and Millie is a success every way but financially.” (And having a boyfriend-and-then-spouse who has a normal person job, and doesn’t mind supporting you while you try and figure out your comics career, is pretty huge at that stage.)

And, to get to your specific question, it was about both uncompromising self-expression AND how the audience was receiving it. I was young, I was a boiling mess of confusion and frustration, and the strip was how I expressed that, so I was never just writing what I thought my audience wanted, but also, connecting with that audience was always part of the point, and why I kept going.

I think I found an audience that wanted the thing I wanted to make. That’s advice I give younger cartoonists now. Don’t try to guess what people want. Make what YOU would want to read. There are eight billion humans. Nothing you can think or feel is unique. If you’re honest, and do what you’re passionate about, it will be what someone other than you wants, too.

This brings me to a bit of a taboo topic, although one you might feel better discussing now that it's a somewhat distant subject. Between Ozy and Millie and Phoebe and Her Unicorn, you made a comic called Raine Dog, which developed a somewhat infamous reputation for merging your generally cute art style with a rather mixed metaphor- funny animals in a human world with serious political stakes, perhaps best known for the "I'm the first girl you spent the night with" page. I'd like you to explain, in your own words, what you were going for with Raine Dog.

If we’re going to talk about Raine Dog, I think we also have to talk about the fact that I came out as transgender in 2005.

And we have to talk about how that went. 2005 was another world, in terms of trans acceptance. The vast, vast majority of people had never knowingly met a trans person. There were no trans influencers, no trans celebrities. You couldn’t watch a sitcom or a comedy film without running into a bunch of “hur hur men who want to be women are so gross and funny” humor.

I think today, people who view themselves as tolerant are aware that trans people are one of the groups they’re required to be nice to. That was very, very not true in 2005.

So I came out, and asked people to please call me Dana and consider me a woman, and…some people were cool about it, but many, many people were not. I became a punchline on forums like Portal of Evil, 4chan, and Encyclopaedia Dramatica, including numerous people who thought it was the height of comedy to try to troll me into killing myself. I became the topic of debate and ridicule on my own forum—I had to publicly disown the Ozy and Millie forum that existed at the time, because its membership decided it was perfectly acceptable for them to make crude anatomical jokes about me, and refuse to gender me correctly. And any time I objected to any of this, it just fanned the flames. “Hur hur, tr*nny butt drama.” I had to learn to just pretend to be unbothered, and scream into a pillow if I needed an outlet.

Even people who weren’t trying to destroy me were often very unkind. People who had expressed admiration for my work in the past would say things like “yeah, Ozy and Millie is great, too bad the creator has gone crazy.” People acted like maybe I had made the whole thing up to get attention. (“Hey, so I have a dedicated and respectful audience, but what I really want is for a bunch of idiots to make penis jokes at me.”) People acted like the abuse I was getting was my fault for doing something abnormal.

It was really rough. I think people forget how recent modern trans acceptance is, and how viciously cruel the internet was in the aughts, even compared to today.

So I took years of mockery and abuse just for being trans and asking for basic respect. But by 2009, I felt like that was mostly over. The trolls seemed to have decided I wasn’t giving them the public meltdown they obviously wanted, and had slowed to a trickle. Maybe once every few months, someone would come at me, I’d do my best to ignore them until they went away, and that was kind of just the background noise of my life, but that was a big improvement from a couple years earlier.

I think that’s necessary context for understanding Raine Dog, both as a comic and in terms of the reaction it provoked.

The genesis of it was Thomas K. Dye’s comic Newshounds. Sorry to Thomas for bringing him into it, but he’s a longtime close friend of mine, and his comic was set in a world where dogs and cats are sentient and anthropomorphic but still live in a world run by humans. They have owners and are obviously second-class. But it’s set in a big liberal city, where most of the time they’re allowed their dignity and independence as people.

Something about that spoke to me. I was still processing having gone from being seen as a white dude, one of the most privileged groups of human beings on the planet, to being an out trans woman in the era before trans acceptance had really even started, and there is absolutely a kind of shock to finding yourself suddenly a second class citizen. Thomas’s universe provided a metaphor for that experience that resonated with me.

I thought about that universe, and what it would be like to exist in it. Particularly, what it would be like to be a sentient animal, a person in any philosophical sense, but to live in the more regressive parts of Thomas’s world, where there was still a firm social order, and where asking for respect would be treated as either ridiculous or threatening.

And one day, when I was sick with the flu and pretty high on medication, I came up with this story.

About a dog in a world like that one, who was a rural pet. As a puppy she doesn’t know she’s second class, just that she’s loved and has room to run around, but as she grows and finds herself, she asks, why am I not allowed in the store, the library, the human bathroom? Why can’t I go to school? Why am I second class? And getting back the answer, “because of what you are.”

I wanted to tell her story. The story of this dog who’s the equal of any of the humans around her and just wants to exist and be herself, but has to fight for that. The story was, when she finds that she’ll never get that where she is, she runs away and goes on a journey that takes her to the big city. Along the way she has various adventures.

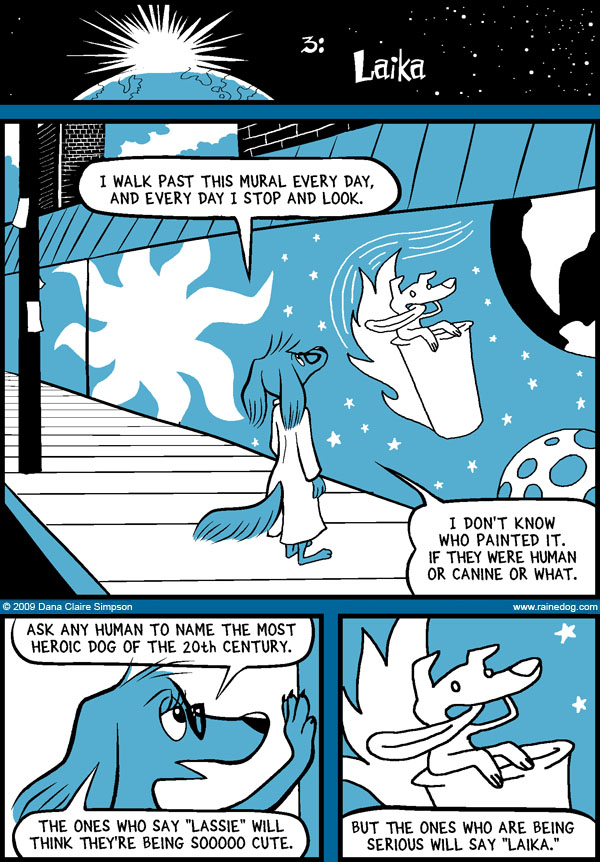

There’s a chapter I’m still proud of, where she learns about Laika the space dog, and is proud that a dog like her could be such a pioneer, but then is horrified to learn that Laika was sent up against her will, to die, because unlike a human, she was disposable. In another chapter, she meets a herd of cows in a slaughterhouse pen and tries to free them, only to find that none of them will believe her that they’re in any danger. She also tries to hunt, to live like a wild animal, only to find she doesn’t have it in her and needs to live in civilization.

Finally, she’s picked up by animal control, and nearly euthanized, but adopted at the last minute by a friendly city-dwelling young woman looking for company, and finally reaches the big city—only to find her rights are limited there, too. She runs for mayor on a whim, and finds she’s accidentally started a movement for equal rights for animals. This is both exciting and terrifying, and not what she signed up for, but she attempts to rise to it, survives an assassination attempt on Election Day, loses, and winds up being able to live a relatively quiet life in a city that now treats folks like herself a little better.

Raine Dog, accidental animal civil rights hero, who really just wanted to be treated like anyone else.

I still think that’s not a bad story. And at a time in my life when I was asking the world simply to accept me and let me live a normal life, and meeting what seemed like an unreasonable amount of resistance, it was a very personal one.

How did the reaction to Raine Dog at the time make you feel? And how does it look in retrospect? Did it, or does it, seem more malicious or more just, lol, look at this silly thing on the Internet?

The reaction to it in some quarters caught me completely off guard.

Now. First of all, for the record, I don’t think what I wrote of it is that good. That’s one problem with it. I had never written a long-form graphic story before, only comic strips, and I made the mistake of thinking I could just write it as I went along, so the pacing isn’t very good. The framing device of Raine in the modern world, kind of telling the story of how she got here, seemed good in my head but really slows the action down. I learned a lot from that about how not to write a graphic novel (things that helped make my subsequent graphic novels much better I think). But learning as I went had never been a problem for me before.

The bigger story is that I, once again, made the mistake of thinking people would approach it with an open mind, and they really did not. “Simpson has gone crazy, ha ha” was still a common take on me in many circles, so Raine Dog was interpreted as uncharitably as was humanly possible.

In particular, the scene in which the title character, as a puppy, and her young human owner, spend a stormy night together in bed.

They are just sleeping! That’s it! They’re kids! It did not cross my mind that anyone would see it any other way.

In the morning, they share a chaste peck on the lips. Exactly the kind that I remember having with another kid in kindergarten. The humans in the story freak out about this, which was meant to read as an obviously prejudiced response to something that, between two human kids, would be completely innocent and uncontroversial. That was the point of that scene.

And boy did people misinterpret it. Maliciously, I firmly believe.

You really have to remember that in many people’s minds, I had gone from being a nice person who drew cute, PG-at-most comics, to a mentally ill sex weirdo, simply because I had come out as transgender. I was the same person I had always been, nothing had changed but my gender, but in a lot of people’s minds I had relocated myself to the corner of Sodom and Gomorrah. And they went into it with that bias.

And I was completely unprepared for that. I naively thought that if fans of Ozy and Millie didn’t like it, they just wouldn’t read it. I still think that would have been the normal reaction, and probably is what would have happened if I had written it five years earlier. Or five years later, for that matter. It hit at a moment when people were actively looking for evidence that I was now a deranged pervert.

So people took that one page, out of context, and spectacularly misrepresented it. A page with a totally chaste kiss was described frequently as “that dogf*cker comic.” One person emailed me just to say “rot in hell, furf*g.” Another person spammed “FURF*G DOGF*CKER” hundreds of times all over every page of my DeviantArt account.

Someone emailed me to say that he used to be a fan but had seen that page on 4chan and now found me “creepy.” I convinced him to read the whole story, not just one page out of context with LOOK AT THIS FREAK or whatever as the caption. After doing so, he actually apologized to me.

At one point, frustrated, I posted “go ahead, call me a freak, just remember freaks do all the interesting and important things,” and got an email smugly lecturing me that I was not the GOOD kind of freak, who makes important art, but rather the BAD kind of freak.

So, yeah. I came in for another round of abuse, as vicious as the first and very similar in character. And I believe with absolute certainty that transphobia was at the heart of it. I was trans, and therefore a sick weirdo perv, and I think that prejudice is inseparable from the reaction people had to it.

And yes, that hurt a lot. I felt like, what did I ever do to any of you? I've been entertaining you, basically for free, for ten years now. So I made one thing you personally don't care for. Why do I deserve this abuse? Leave me alone.

I’m still angry, when I think about it. So many people owe me apologies I’ll never get. But I won in the end, I think. The last laugh was mine.

What I would say to people now is: if you liked Ozy and Millie, and you like Phoebe and Her Unicorn, if you appreciate everything ELSE I’ve made, maybe you just didn’t understand that one. Maybe you were blinded by prejudice, or let the internet hive mind do your thinking for you. Maybe you were wrong.

Did you find it was pretty easy to move on once Phoebe and Her Unicorn got going?

So the timeline of events is: I ended Ozy and Millie in December 2008. I started posting Raine Dog at a rate of like 2-3 pages a week in January 2009.

By June of 2009, I was getting a ton of vicious abuse, plus I wasn’t really happy with the pacing of my story. I had written about a third of the story--up to the point where Raine is captured by animal control--and I chose to put it on hold to retool it. And I do think that if I had restarted the story, as I planned to, it would’ve been stronger.

But fate intervened, because in August I entered the Comic Strip Superstar contest, (spoiler alert) I won. For those who don’t know, it was a talent search contest Andrews McMeel held online, in which the prizes were a book contract, online syndication, and a newspaper syndication development contract. It’s how I finally, after so many years of trying and failing, got my foot in the syndication door.

During the contest, when I was one of the ten finalists, someone posted in the comments, "anyone concerned that one of the finalists endorses bestiality?" That was what the chaste kiss on one page of a much longer story had become online. Me "endorsing bestiality."

And my heart sank, like, is this just who I am now? Did 4chan successfully redefine me in this way?

But all of the responses were along the lines of "stop it. We don't treat people that way here." That lifted my spirits. And it was a sign of things to come.

Because once I won, abusive references to Raine Dog dwindled to almost nothing. It was striking how suddenly that happened. I still don't know exactly why it happened so quickly.

There was a period in between my winning that contest and the launch of the new strip (which I originally called Heavenly Nostrils, but we'll get to that). I didn't even sign the contract until six months later, in like March 2010, and then I was submitting roughs in an attempt to develop a strip they'd want to launch for about a year and a half (I had a 2-year development contract), and so the internet didn't hear from me much during that time.

Which was fine with me. I was sick of the abuse, sicker than I think I can describe in text. Dropping offline to develop something new for a bit was just fine by me.

But that did prompt some rumors. Where did D.C. Simpson (the name I mostly used back then--my middle name is Claire) go? I heard various rumors about myself. My favorite was that I'd lost my development contract for "plagiarizing myself," which I don't think is a real thing, and subsequently gone into seclusion.

Then, finally, in 2012, I announced and then launched Heavenly Nostrils, on gocomics.com. It was popular pretty fast, enough so that I saw a few "Simpson is back, and this strip is good, so let's all stop mocking Raine Dog" kinds of takes.

It was basically never a problem again. Every few years, someone on social media will be like "aren't you the crazy person who made that dogf*cker comic?" And I block them and never think about them again.

I suppose the best theory I have, for why that went away so fast, is one a friend of mine proposed: online hate is often a way of saying "you squandered an opportunity I should have had." People who liked Ozy and Millie and hated Raine Dog were contemptuous because they thought I'd squandered my talent and popularity on some perverted weirdness (again, I believe this to be unexamined transphobia). But once I won the contest, and especially once I had a new strip that was a hit, I no longer seemed like I'd squandered anything.

It's as good an answer as I've ever found.

Something else that has to be said about Raine Dog, though: not everyone hated it. In fact, it had its big fans, and still does. It's some people's favorite Dana Simpson comic. Literally yesterday, a fan on Bluesky told me it helped her find herself, as a transgender woman. It's not the first time someone has told me Raine Dog was there for them when they needed it.

I may lament how it was received by some people. But I can't regret making it. If it was important to someone, loved by someone, helpful to someone, then by at least one very important measure, it's a successful work of art.

A rain dog is a dog that's lost because its scent trail has been washed away by the rain, so it can't find its way home. Raine Dog is almost that. But not quite, because she lives on in at least a few hearts.

Why Heavenly Nostrils? And whose idea was it to change the title?

The syndicate never liked the title Heavenly Nostrils. (For anyone who doesn't know, the title is from the name of the strip's star unicorn, Marigold Heavenly Nostrils, a name I got by typing my name into an online unicorn name generator.)

When the strip launched online in 2012, they reluctantly agreed to let me use it, but described it to me as "gross" and hard to market. They said that once it came time for books and newspaper syndication, we'd have to pick a new title. I suppose I kind of imagined people would get used to it--did the name The Flaming Lips seem great the first time you heard it? But no, when it came time for the first book and the newspaper launch, they made me change it to "something that better reflects the content of the strip." Barnes & Noble apparently said they'd buy more copies of the book if we did that.

I didn't argue that hard. I was just excited to have books and newspaper syndication. So I went along, and the strip became "Phoebe and Her Unicorn."

It's hard to argue with how well the strip has done under that name, but I still like "Heavenly Nostrils." My mother hated it, though, so I think it was polarizing. Still, I get people, to this day, insisting they much preferred the old name. And I honestly still do too.

For a while there seemed to be big marketing potential behind Phoebe and Her Unicorn. I think there was something about a possible Nickelodeon adaptation? Why did that fall through?

I suppose all I can say about that is "that's Hollywood for you."

Phoebe and Her Unicorn has been optioned for TV/movies twice: in 2017 by Amazon Studios, and then in 2020 by Nickelodeon. Both times it fell through. In both cases it seems like it was an old Hollywood story: one executive was championing the project, and then that person left and the project got orphaned.

Then they never cut you loose immediately, they just start talking to you less, and making weird demands that suggest they've never actually read the source material, and then eventually they officially cancel your project.

Also, someone at Nickelodeon said something about not wanting to market a strip with two female leads, but I probably shouldn't tell you that because the last time I said it, it leaked out, it got into the comics press, and I ended up having to apologize to people at Nickelodeon. Ah, well. It's the truth, I'm not under an NDA, and what are they going to do, not make my show some more?

At the time, my show got canceled but "Big Nate" moved forward, and I'll admit I was sort of bitter about that, but then after two seasons Nickelodeon abruptly canceled that show and deleted it off stream, casting it into the void, and I think I'd actually have been more upset if that had happened than I was about not having a show at all.

The idea of making a show is still on the table, but it's such a strange time in that industry that I have no idea what's going to happen. I'm just glad I make a good living off drawing comics, so I don't NEED a show. It would just be really cool.

Something I rather liked about Phoebe and Her Unicorn was the excellent use of the traditional newspaper comic format for punchlines. The structure is always very tight. Were you concerned about being able to maintain that rhythm in a television show over which you wouldn't have complete creative control?

It was, and is, certainly something I think about. I got into comics partly because it was a medium where I'd get to make all the decisions, and with a show I'd be surrendering that. And I've said before that my greatest fear wasn't failing to get a show, it was making a show that was bad. Either because I don't know how to write in that format, or because the other writers we'd obviously hire might just not get my sensibility. That it might only work if it's me and if it's comics.

But, you know, creativity involves taking risks, and that's one I'm still willing to take, if anyone wants to let me.

The final arc of Phoebe and Her Unicorn, for those not familiar with it, involves Phoebe moving to a new house. This isn't as dramatic as it sounds, as the house is in the same general area (closer to her friend's house actually), and is also larger and generally just better than the existing house. Most of the comics are about Phoebe trying, and failing, to come up with a profound reaction to leaving her old house. I'm sure this all sounds very obvious now in retrospect, but was this intended as a metaphor for your decision to end the daily strip, which was only publicly announced on March 20th ahead of the March 29th end date?

Yeah, that metaphor was always intentional. I came up with it back in December, when I actually started writing that storyline. It's my way of saying "this is a transition, but it's not nearly as big of one as it might seem, and we aren't REALLY going anywhere, just changing up the creative house we live in." It was also, conveniently, happening as me and my spouse were also buying, and moving into, a new house, so it reflected real events both metaphorically AND literally.

I've known we were going to end the daily strip for months, and I found it kind of comical how long they made me wait to formally announce it. Basically, we had to contact all the papers that ran the strip, before I could say anything, and that took a long time. It was strange being weeks into what was always intended to be the last daily storyline, and not being able to talk about it.

In a sense you do still have that old house. You're still planning to do the Sunday strips going forward, I understand? Do you find them significantly different from the dailies, or is it just a matter of giving yourself more space to work on the graphic novels?

Sunday comics are sort of a different beast than daily comics, although now that I'm only writing Sundays I'm finding myself giving them some continuity with each other, which they've never had before.

But when I started seriously talking about ending the strip, they offered to let me keep the Sundays, something other creators who have retired from the dailies have also done, and it seemed like a good way to go. It lets me keep being a syndicated cartoonist--and I cannot stop, they haven't given me a Reuben yet despite nominating me twice--but frees up a lot of time to work on the graphic novels. Sort of the best of both worlds.

And Sundays are fun. They're a chance to flex a little more as an artist. I like doing them.

Just very frankly speaking, why graphic novels? Are your motivations creative, financial, a mix of both?

A mix of both, really.

I've known for years that this was where I was going to end up. The fact is, as much as it pains me to say this, newspaper comics are in decline, because newspapers are, whereas graphic novels for younger readers have exploded and are showing no signs of slowing down.

And, relatedly, I'm a moderately successful syndicated cartoonist, but a very successful graphic novelist, with (mostly) the same material. My audience is mostly pretty young, so they don't really read newspapers, they read graphic novels. Way more people read me in book form than in newspaper form.

The vast majority of my income is book royalties. The marketplace is telling me, and has been for quite a while, that what people want from me is books. So, why not just give them what they want?

But the other thing is that, yeah, after working on Phoebe for 13 years and O&M for a decade before that, I have drawn thousands and thousands of comic strips and I've grown kind of tired of the format. I don't want to say I've "outgrown" it because it's a great format and I do still love it, but I think it's fair to say I've become a bit bored with it. I feel like I've done most of what I can do in that space. Meanwhile, I have a head full of longer stories just waiting for me to tell them.

It's not the first time I've done it. Two of the Phoebe books are graphic novels, written independently of the strip--The Magic Storm and Unicorn Theater--and I really enjoyed making those. But it's murder doing that AND a daily strip. I look forward to being able to commit all my energies to telling longer stories in a more open format. I'm excited for that new challenge.

We have enough strips for three more books, but I can already tell you the first new one I write after this will be a unicorn ghost story. I've been kicking that around in my head for years.

I've also been working on a graphic memoir about my childhood, for years, that I want to finish and put out, and there's a non-Phoebe project I'm working on with my sister, who is a brilliant artist herself.

I feel excited in a way I haven't in a while. I think that means this is a good time for a new adventure.

Well, those are all the questions I have for you. Are there any other questions you'd like to answer that I didn't ask?

Hmmmmm. Well, yeah, here's one. You didn't ask me about the future of Ozy and Millie. Because that's reasonable not to ask; it ended more than 16 years ago.

But a year or two ago, I had a dream that I wrote a story in which Millie transitioned, and now wished to be known as Milo and referred to as he/him. And I found that intriguing enough that I posted some sketches on Bluesky. And the response was...very very positive. More than one trans guy told me it moved them to tears, because trans guys get so little representation.

My work has never been heavy on trans themes, but this seems like a book that should exist. My agent has encouraged it, too. So, one of the new projects you can look forward to is the Ozy and Milo book.

Again, none of this is to say Phoebe will take a back seat. Phoebe and Marigold will be around forever. There will be at least one new book a year for as long as I have a working frontal lobe and a working drawing hand.

They've more than earned that.

Thank you again for agreeing to this interview. It was great speaking to you.

Thank you! It's been a pleasure. I look forward to learning which of the things I just said is going to rub somebody the wrong way. And also which of the things I just said made someone's day. Because usually I get both when I talk this much.

The post Unicorns do exist: Dana Simpson on being a dangerous, freethinking rebel at 700px appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment