I was in a conversation with a professional artist once, and found myself in a rare position. That position being: defending the artistic value of American superhero comics (they can take away your Comics Journal license for that). I wasn’t defending it overall, not as a phenomenon, simply pointing out that there is enough stuff there (Kirby’s Fourth World, Ennis’ Punisher Max) that I would classify as art with a capital A. My opposite number in the conversation, a person who had worked on several corporate I.P. gigs, was pretty blunt on calling the whole thing fluff, at best a passable bit of entertainment. Just as I was ready for another round of examples (does X-Statix count?) the creator interjected: "The one exception is Daredevil by Ann Nocenti and John Romita Jr."1. My ears perked at this. The obvious choice when talking about runs of Daredevil comics regarded as a critical high point is the Frank Miller version. But no, Mr. Comics Maker was adamant — Nocenti and Romita Jr. were the high point. Not just of Daredevil2 but of all superhero comics.

I never read that run before. But I kept this statement in mind. And now, with Marvel releasing the first half in one of these big expensive omnibus hardcovers, I recalled the words uttered in that large and loud room. Against my better judgment, against my experience, I decided to give it try. Why against my experience? Because I wasn’t so hot on the creators.

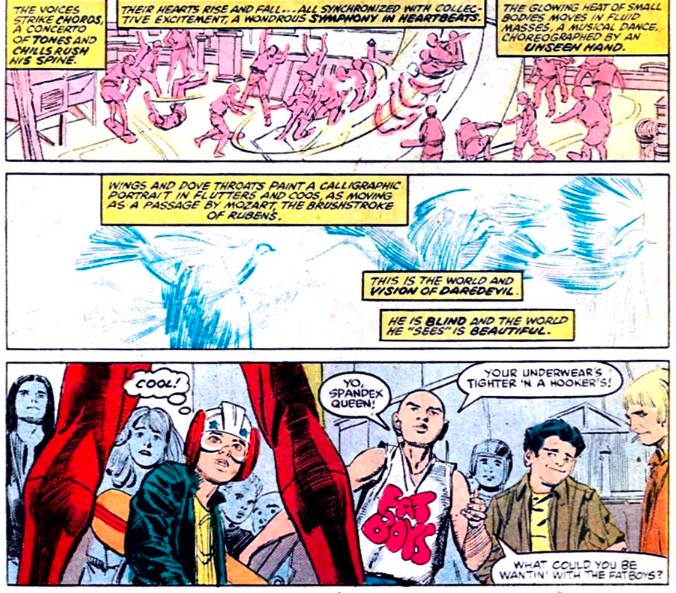

I loved Romita Jr’s art, as all right-thinking (right-seeing?) people do. His reputation has somewhat diminished over the last decade, but to me even diminished Romita Jr. is preferable to 87% of superhero artists. It is true that he doesn’t quite hit the home runs of his heyday. It is also true that even at his best there was often something uneven about him (the same issue could contain scenes of absolute dynamic power and some slapdash shortcuts). It is especially true that the Overton window of superhero art had long since moved away from his grimy faces and acrobatics to a more "clean" direction. Everyone wants to be Dan Mora these days (one is enough, thank you).

Yes, he’s not the powerhouse he used to be; very few people are. He probably can’t amaze us as he did on Man Without Fear. So what? Can you draw something on the level of Man without Fear? Is there, amongst the readers of this article someone else who has done the best rain-splashes-on-a-filthy-street since Will Eisner? Probably not. There is a story about Joseph Heller being interviewed by some young critic who asked him something to the affect of "Why aren’t your other books as good as Catch 22?" to which the older writer replied, "Did anyone else recently write a book as good as Catch 22?" Romita Jr. set himself an insanely high bar.

If I like his work so, why the hesitation? The reason being: there are fewer talented people in comics who are less picky than Romita Jr. The man would draw anything at a pretty fast rate, and as a result his few gems are surrounded by crap mountains barely elevated to decency by his pencils. If John Romita Jr. grew up in Europe he would do 60 pages a year and would have the reputation of a modern Michelangelo; but he grew up in the United States and drew 300 pages a year and as a result has a reputation of someone who can draw a mean Michelangelo (of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles fame). Comics is filled with talented artists wasting their time on mediocre-to-bad scripts, but few have such terrible ratio of good-to-bad as Romita Jr. The man is an artist who seemingly doesn’t believe in art.

Ann Nocenti is a different matter. I knew her by reputation long before I read a single book by her. In fact, I believe my first full exposure for her work was during the DC New 52 Era (she wrote Green Arrow and Klarion for a bit). These were terrible comics. I don’t blame her, no one was on their A-game in that period, with editorial seemingly confused at what exactly they were trying to produce3. Going further back I gave a shot to her Typhoid Mary miniseries (more on that later) and her Longshot with Art Adams. Better, but still far from good.

I had categorized her work, in my mind, as part of the "Gerber Zone." The cadre of superhero writers whose influences were wider than their contemporaries, who wrote in a slightly outre fashion, who obviously wanted to say "something" about the real world, who had ambitions … who nevertheless produced bad comics. I know there is a whole generation of Steve Gerber fanatics, but to me he illustrates the difference between "interesting to write about" and "good." If you only read Stan Lee-wannbe slop it hits you like the prose of J. G. Ballard, when what it’s closer in level to one these stories from the flabby middle of Dangerous Visions.

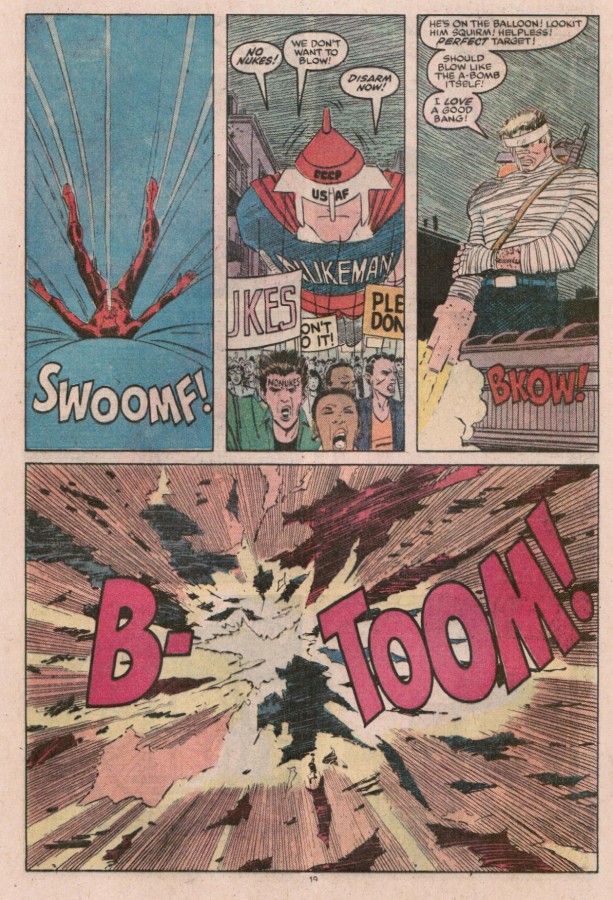

Still … open mind, open mind. I trusted that comics professional (in matters of taste at least). I like that general period of superhero comics (still a lot of slop, but most of the big hits come from there). I love the art of John Romita Jr. I decided to give it a shot. First thing I should probably mention: John Romita Jr. doesn’t draw a single sequential scene before page 350. Granted, an omnibus is a big book. Also granted, he does most of the second half of the run. But I consider that false advertising. Not that all the pinch hitters are bad. Barry Windsor-Smith does his usual best, Sal Buscema does his usual dependable and Keith Giffen does his usual Munoz copycat act (not that it’s a bad thing to succeed at copying Munoz). Still, for all the talent before him there’s a reason the first Romita Jr. 4 issue opens with a nuclear explosion — the creators seemingly realized what they got in their hands. Everything before is not bad by its own right, but becomes an afterthought when Romita Jr. enters the scene like a freight train.

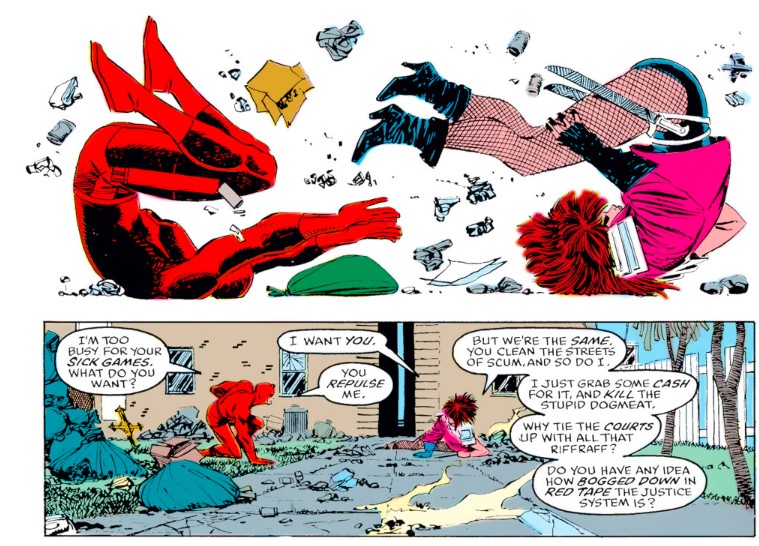

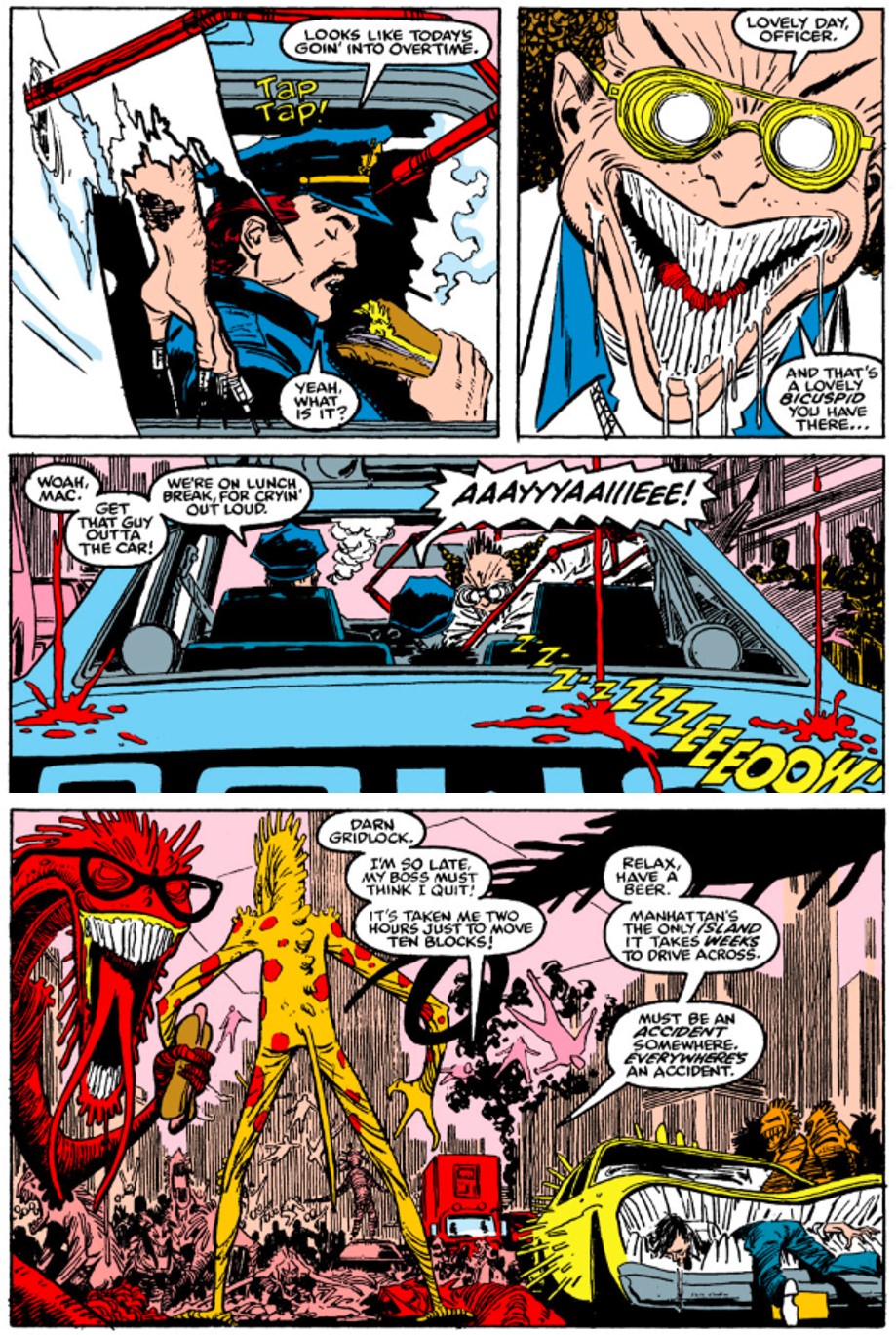

He’s like his father in that regard. Not a clone of the old man, but evoking the same sense of modernism Romita Sr. infused when he took over Spider-Man. The two had to follow the toughest of tough acts and each made it work by going from gritty to pretty. It’s true that the streets are dirty, that the crooks have bruised faces straight out of Chester Gould (and that’s before Daredevil starts punching them), that the monsters in the Inferno tie-in issues have the twisted charm of a Ted McKeever design … but what I take from that run is sheer style. It’s hard to think of Romita Jr. in these terms, now that he’s an old man himself, but in the 1980s he drew the way Michael Mann movies looked. Matt Murdock, Karen Page, Typhoid Mary … they are doomed and beautiful.

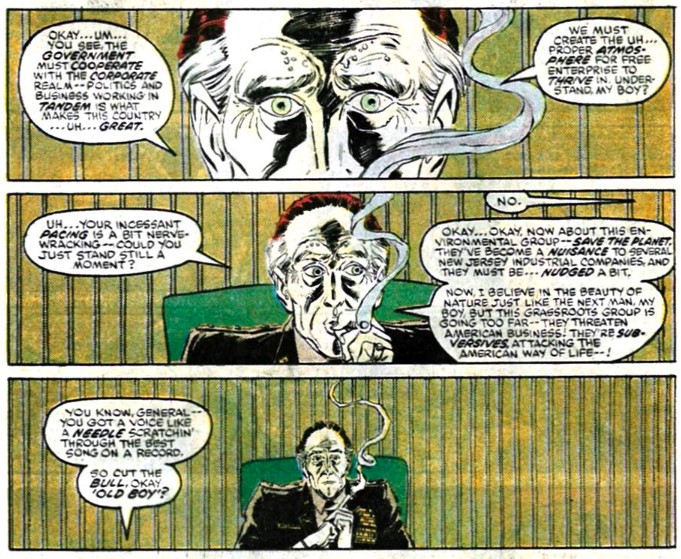

I don’t know if it’s me growing older, or if there is something truly different about Daredevil, but all Nocenti’s writing ticks that bugged me before clicked on this book. The characters still have a tendency to soliloquy, to state their mental state in a manner that is both straightforwardly earnest and faux-poetic The socio-political tones of the book are oft confused, but not because Nocenti isn’t sure what she’s trying to say, but because the characters themselves are confused. Like another beloved slice of 1980s superheroics (The Question by O’Neil and Cowan) Daredevil is a story of man unsure of himself, a lost soul in search of direction.

Miller might have set that particular course, which everyone else followed, but Nocenti took to its conclusion — a man split is a man lost. Matt Murdock uses Daredevil as an excuse to avoid confronting the contradictions in his inner-self, and the longer he goes the more this contradiction tears him apart. That sort of thing is an old hat these days, but thankfully Nocenti doesn’t fall to the inward-looking pit that has consumed much of superhero comics. This isn’t a work about Daredevil, this is a work using Daredevil to explore the inner turmoil we all go through. Daredevil is a series of big ideas; it might not develop all of them fully, but it is trying. It is trying so very hard.

One early issue seems eerie prophetic of the Luigi Mangione murder case (still in the courtroom at the time of writing). Unlike the actual occurrence, the killer here is a poor schlub that murders his boss in a fit of anger, but with the description of media landscape that turns him into an unwilling superstar. Years before social media Nocenti was writing a story about how people are forced into becoming caricatures of themselves, a flat representation by people unwilling to perceive a three-dimensional reality. As the issue goes on we see Daredevil caught exactly in the exact same trap — seen by other as a simple thug, trying to solve everything with his fists. As he tries to find another way he starts to wonder if the media is right, maybe he really has nothing else to offer.

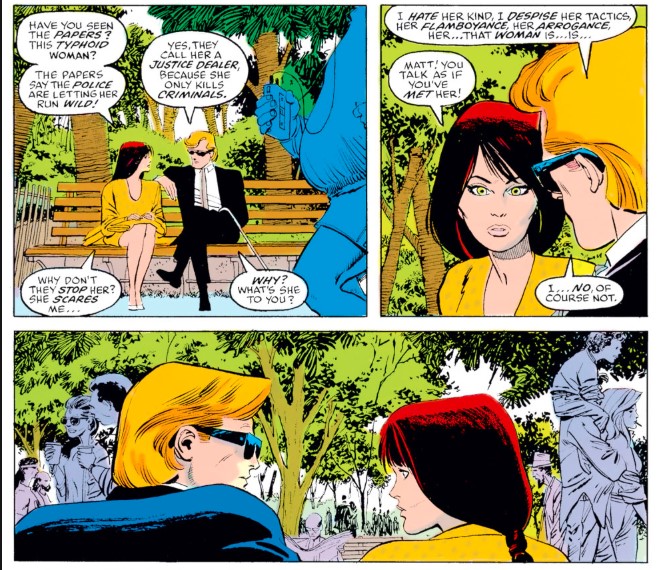

That theme becomes more apparent with the introduction of Typhoid Mary, probably the most memorable part of the run. At first she appears to be another one of these mirror-villain figures that is meant to illustrate something about the hero. She’s an extreme version of superhero identity split — with non-powered Mary seemingly unaware of what her other half does — the only way to hold two people in your head is to literally be two different people. So far, so generic. But there’s more to it in her appearances here. Typhoid Mary also plays along the Madonna-Whore complex, with the woman being the entirely submissive and nice Mary or the dominant and sadistic Typhoid. In short, she is defined in her relations to the men in her life, who always end up using her as an emotional crutch. Daredevil spends large chunks of the story angry that people can’t see him for what he his (or what he thinks it is), and at the same time he can’t see beyond the façade of Mary.

The final act of this trade, a long horror-tinged storyline set-up as a tie-in to the X-Men Inferno crossover, brings all these themes to new heights (alongside Romita Jr’s art), as New York becomes hell on Earth and people view it just a continuation of what has gone before. Hell is other people after all, and there are so many other people to hate in New York City. It’s a long and rumbling story that somehow manages to feel like a proper extension to the small-scale storytelling that has gone before. It’s not an entirely satisfactory story. The journey is more impressive than the end (Mary herself is shoved more and more to the side as the story becomes more supernatural), but it’s good enough that you can forgive its faults.

Daredevil by Nocenti and Romita Jr. is far from perfect comics. It has all that faults one would expect a Marvel product of that period. The stop-start nature of superhero comics at the time means we get a completely unrelated fill-in issue right before the big climax, (drawn by Steve Ditko, doing retro-work for a maximum stylistic whiplash). The series must also spend time explaining what has already been explained and satisfy the creative demands of the editors (not to mention the tie-in demands of other titles). It shouldn’t work. It certainly shouldn’t be Art. But it is. It’s ramshackle art, stumbling when it should be walking tall, but it’s art nonetheless. That comics pro was right, or at least half right, it not might be the highest achievement is superhero comics, but it is certainly in the running.

***

The post Daredevil by Nocenti and Romita Jr Omnibus volume 1 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment