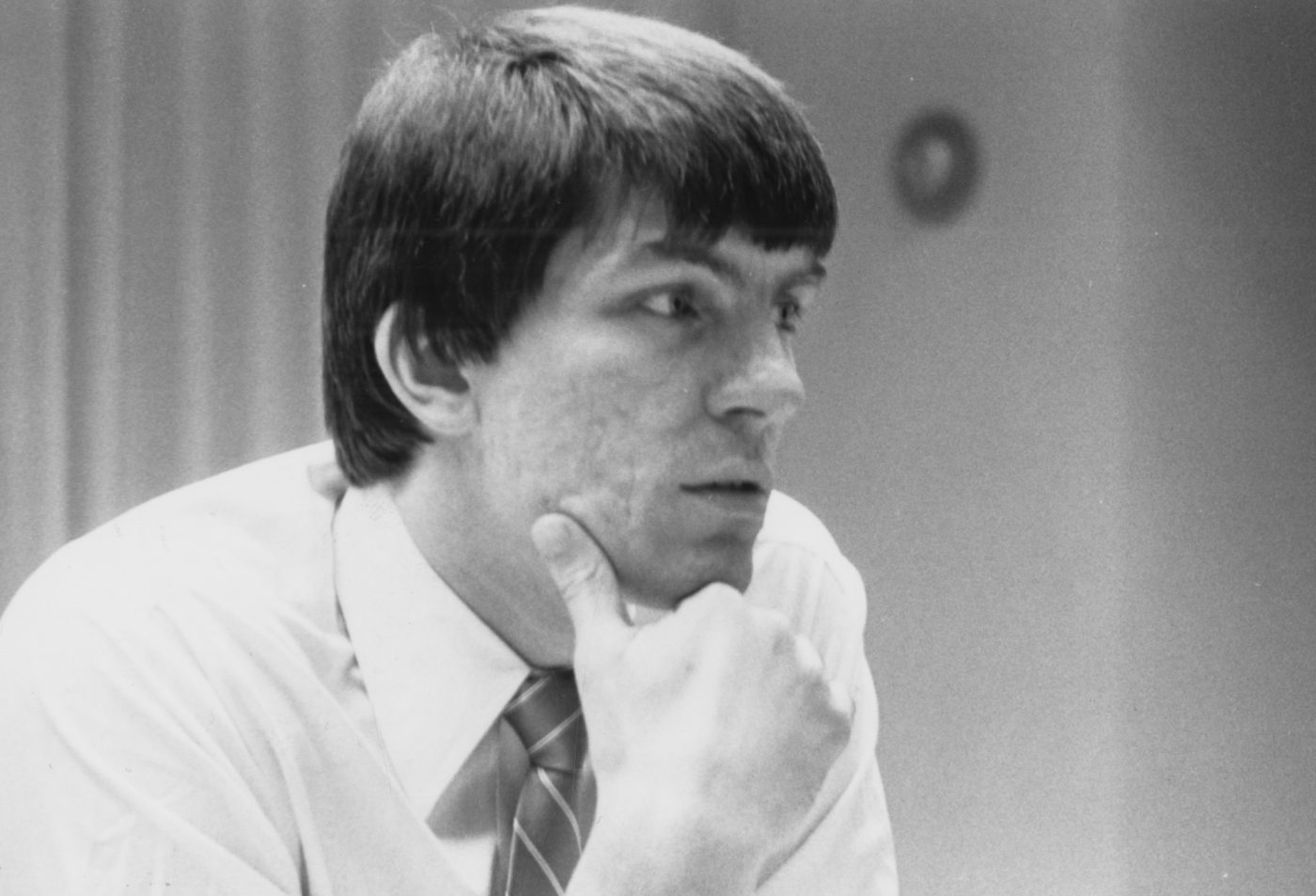

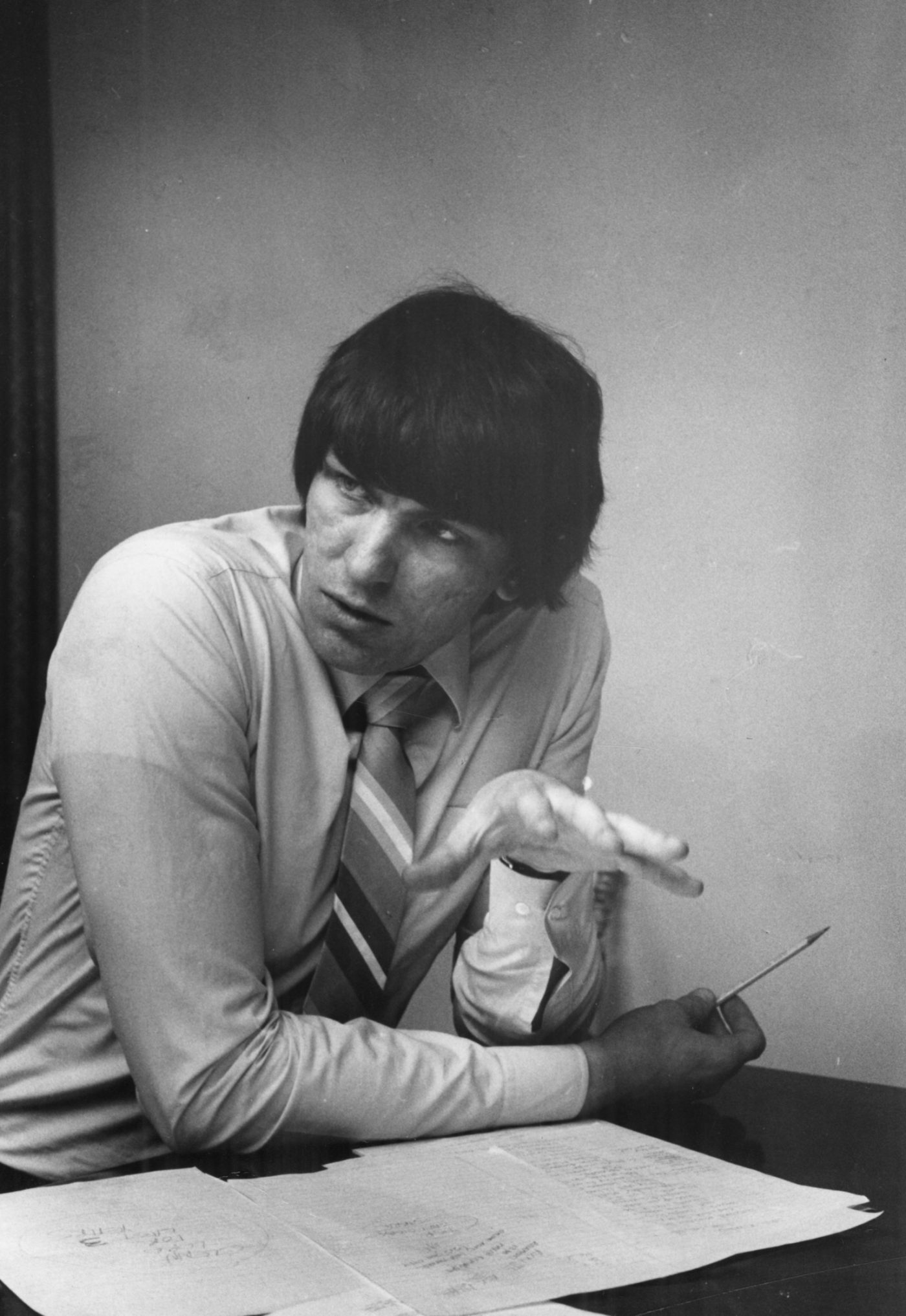

James Charles “Jim” Shooter, who died after battling esophageal cancer on June 30th, 2025 at his home in Nyack, New York, is one of the most controversial and divisive figures in comics history. His long career in the industry boasted both amazing accomplishments and demoralizing failures. But, to Shooter’s credit, he never allowed career setbacks to keep him down.

Ask anyone who worked with him about Shooter’s personality and editorial abilities and you’ll receive a wide variety of responses. He was simultaneously one of the most reviled figures in comics, and yet one of the most well respected, it really depends upon whom you talk to. Comics Journal publisher Gary Groth was certainly no fan. He wrote multiple editorials excoriating Shooter’s editorial tendencies and his personality as well, sometimes likening him to among others, disgraced ex-president Richard Nixon, (TCJ #174), a plantation slaveowner (TCJ #115), or even a Nazi collaborator (TCJ Library: Jack Kirby). Others in the industry, including some of the creators he nurtured and encouraged during his tenure at Marvel as its Editor-In-Chief, including Chris Claremont, Bill Sienkiewicz, Jim Starlin, and Frank Miller, regarded him more favorably.

Starlin was quoted by R.S. Martin as saying: “As editor-in-chief Jim rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. Because of this he has been unfairly uncredited with all the benefits he had a hand in gaining for artists while he was at the helm. He did a lot more good than ill while he was the boss.” After Shooter’s firing in 1987, X-Men scribe Chris Claremont commented in The Comics Journal (TCJ #116), “Things that were better [at Marvel] were better [because of him].” Bill Sienkiewicz, who gained fame in comics drawing Moon Knight and The New Mutants, told Forbes that Shooter "really polarized people, but it was because he had a passion for what he was doing …He went to bat for freelancers in a way you don’t see many people in editorial roles do today.”

Jim Shooter was a complicated man, undeniably talented but sometimes tactless and domineering, perhaps because of his hard-scrabble childhood and youth in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was not a smooth-talking glad-hander like Stan Lee, and because of his height and brusque manner, he certainly intimidated people, his freelancers and editors among them.

Shooter was born into a blue-collar family. His father was a steelworker, and money was always tight. As a child, he read comics the way any kid reads comics, just for fun, and around age eight, he stopped, at least temporarily. Then, at age 13, while being hospitalized for an operation, he discovered Marvel Comics and was immediately taken with Stan Lee’s hip, energetic writing, which was a far cry from the staid house style of the DC Comics he had been reading years before. At some point after this, Shooter decided that he wanted to give writing comics a try, so he spent about a year reading both Marvel and DC Comics so he could understand storytelling and the different styles each company represented. He naturally gravitated to Marvel’s style, which involved creating more complex, layered characters.

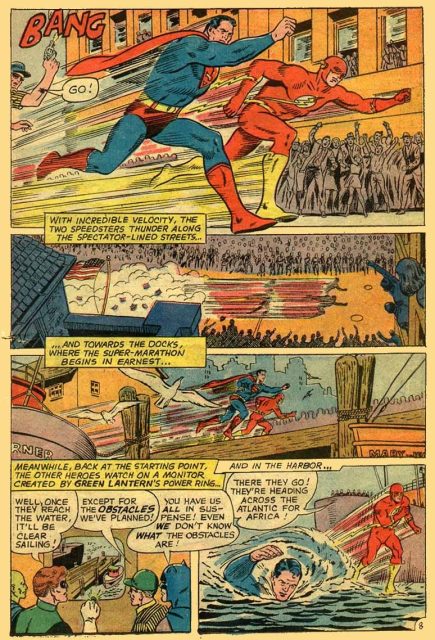

In 1966, at the age of 14, Shooter was submitting scripts to DC, and began working for long-time editor Mort Weisinger on titles like Action Comics, Adventure Comics, The Legion of Super-Heroes and the toy-inspired Captain Action, (for which he only wrote the first two issues since penciller Gil Kane wanted to take over the writing). Although it was tough for the teenager to work for Weisinger, who was notorious for his cruelty, Shooter stuck with it, and his work struck a chord with DC’s readers. During this time, he created the Karate Kid, Princess Projectra, Ferro Lad and the classic villain team The Fatal Five. He also added to the Superman mythos by creating the villain known as The Parasite. Working with veteran Superman penciler Curt Swan, Shooter came up with the idea of having Superman and the Flash race each other to decide who was faster (Superman #199). Although his writing checks were a welcome addition to his family’s income, after a couple of years, Shooter left comics to complete his education, despite becoming something of a local celebrity in Pittsburgh because of his precocious writing talent. Shooter, however, did not attend New York University for very long. He tried working for Marvel as a plotter and editor, but after three weeks, Shooter quit and went back to Pittsburgh. Back in his home town, he worked in advertising and other ordinary, non-comics-related jobs.

By the early '70s, Shooter had returned to writing for DC Comics, penning more Legion of Superheroes, Superboy, and Superman scripts. However, he did not enjoy working with editors Julius Schwartz and Murray Boltinoff. Shooter’s drive and talent did not go unnoticed over at Marvel, and in late 1975, then-Editor-in-Chief Marv Wolfman hired Shooter as an assistant editor, replacing Chris Claremont, who had quit to focus on freelance writing. The mid-to-late '70s was a tumultuous period for Marvel, after Stan Lee’s departure as editor-in-chief, and for the next few years, several different creators filled that role, including Roy Thomas, Gerry Conway, Len Wein, Archie Goodwin, and Wolfman. By 1976, Shooter was an assistant editor and scripter.

The rapid churn of editors created opportunities for the ambitious and hard-working Shooter, and only two years after joining the Marvel staff, he succeeded Archie Goodwin in the editor-in-chief job. Because of all the staff turmoil, Shooter was actually the ninth editor-in-chief, assuming that role on Jan. 2, 1978. By this time, Stan Lee was fully immersed in his new job of promoting Marvel properties in Hollywood, and Shooter became responsible for all the creative decisions at Marvel Comics.

Shooter quickly realized that Marvel Comics was a mess, with constantly missed deadlines that resulted in late charges for some books, and a comics company that lacked a coherent editorial philosophy. Shooter cracked down on his creatives to make them more deadline conscious, and instituted strong editorial control over the books’ content, which caused some grumbling in the ranks and led to Shooter’s negative reputation among many Marvel freelancers who’d become accustomed to a more laissez-faire attitude.

At the same time that Shooter was making Marvel’s operations more streamlined and businesslike, he was also encouraging his top creators. That included: Frank Miller, who was doing groundbreaking work on Daredevil; Roger Stern, who had successful periods writing both The Amazing Spider-Man and The Avengers; Chris Claremont, who, along with penciler John Byrne, took the X-Men from a second-rate superhero title to the heights of popularity; and Walt Simonson, whose refreshing take on The Mighty Thor made the comic a bestseller again. Shooter also raised creators’ rates, instituted a royalty system and created the first direct-sales-only title, The Dazzler, which was based on an abortive film starring Bo Derek. Shooter was highly successful at making Marvel the most profitable comic book company in America. At its high point under Shooter’s editorship, Marvel accounted for as much as 80% of comic book sales in America.

Still, despite his amazing success at turning around Marvel’s fortunes from the late '70s through the mid-80s, his strict editorial style and brusque personality led to many top creators jumping ship and going to work for DC, including long-time Marvel stalwart Gene Colan, Master of Kung Fu scribe Doug Moench, Howard the Duck creator Steve Gerber, and eventually John Byrne, who by the end of his Marvel tenure had become a superstar because of his work on such titles as Alpha Flight and Fantastic Four. Even Frank Miller left the wildly popular Daredevil in 1983 to do his original Ronin miniseries for DC.

Marvel’s behavior towards Jack Kirby is yet another reason that many pros and fans continue to paint Shooter as a villain. As editor-in-chief, he was the face of a corporation that treated Kirby, the co-founder of the “Marvel Age of Comics” very poorly, to put it mildly. When Marvel began returning art to the creators in the mid-1980s after warehousing it for years, it was estimated that Kirby had created some 8,000 or more pages of art. However, Marvel only offered Kirby a paltry 88 or so pages. The rest of it was unaccounted for, possibly damaged in a warehouse flood and then discarded, or given away to fans visiting the Marvel offices in the '60s and '70s, or outright stolen by greedy or disgruntled staffers. There’s also a rumor floating around of a Marvel editor (who shall remain nameless due to a lack of documentation) who was fired by Shooter, and, upon being terminated, went to the art storage area and loaded up a considerable number of choice pages in the freight elevator and took them downstairs when he departed. On his way out, said editor supposedly told some of his colleagues that he had arranged his own “severance package." Whether or not this story is true is still open to debate, but there was a certain amount of pilfering of original art over the years.

Needless to say, when it came to light how little of Kirby’s art was being returned to him, there was a universal outcry in the industry and fan press about the shabby treatment of one of Marvel’s founding fathers, and a beloved figure in the comics community. Compounding this situation was the fact that Marvel pressured Kirby to sign a unique-to-him release form surrendering his rights to the many characters he had created before they would release the original art. What's more, he would only have the rights to store that artwork; he wouldn't be allowed to sell, make copies or even exhibit it.

These decisions were certainly not solely made by Jim Shooter, but by then-President of Marvel Entertainment James Galton, his boss, and other high-level executives. Still, since Shooter was the public face of Marvel Comics, he took a large share of the blame, further blackening his reputation. After some legal maneuvering, Kirby signed some amended documents and in 1987 was given 1,900 pages of art, though it was a somewhat Pyrrhic victory for the veteran artist. To this day, many in the fan community blame Shooter for Marvel’s poor treatment of the man mostly responsible for the creation of the original Marvel universe.

One of Shooter’s editorial policies that caused the most controversy was his ban on gay characters in the Marvel Universe, which alienated more broad-minded creators and fans. Shooter even wrote an anti-gay story in The Rampaging Hulk black and white magazine (issue #23) in which two men tried to rape the Hulk’s alter-ego Bruce Banner in a shower. That kind of small-mindedness did no favors towards altering Shooter’s prickly reputation.

Although Shooter’s hard-driving editorship made Marvel wildly profitable with a rainbow of projects such as the miniseries Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars (1984-1985, Shooter also scripted the series), a number of toy tie-in titles like The Micronauts, Rom, Hasbro’s GI Joe, among others, he was not wholly unerring. His attempt to vastly expand the Marvel Universe with a whole slate of new characters in his New Universe titles was a bust. Within a year, four of those eight new titles were cancelled, and although some of them ran for 32 issues, they were eventually cancelled too, due to pressure from Marvel’s owners, who wanted the focus to remain on their established characters. None of Shooter’s new creations were especially memorable, and although some of them were used in later mainstream Marvel titles, they failed to achieve lasting success and are barely remembered today. However, Shooter was successful in creating the first company-wide crossover event, something which was copied by DC with their Crisis on Infinite Earths miniseries. Hoping to have another hit crossover series, Shooter created and wrote Secret Wars II (1985-1986), which was Marvel’s best-selling series in 1985, but was almost universally excoriated by the comics press, who found it derivative and poorly-written.

Despite his many successes at turning Marvel into a publishing powerhouse, Shooter did not get along with Marvel’s new owners — New World Entertainment acquired Marvel Entertainment and Marvel Productions in 1986 — and had already ruffled too many feathers with Marvel’s talent and editorial staff with his insistence on iron-fisted control of the editorial content, and a habit of micromanaging everything. His success with the first Secret Wars miniseries also might have given him the pretension that he had infallible instincts for what made a good story. Within that vein, Shooter’s relationship with John Byrne, one of Marvel’s star talents, was particularly contentious, with many creative battles. Things came to a head after Byrne turned in an issue of The Incredible Hulk (#320), where each page was a splash page, something that freaked out editor Denny O’Neil. O’Neil assumed that Shooter would nix such a radical departure from the Marvel standard, and summarily rejected it. Outraged, Byrne quit on the spot and even called Marvel’s president, insisting that Shooter be fired. This incident, on top of many other clashes with Shooter, resulted in Byrne leaving Marvel to reimagine Superman for DC. This is only one of several extreme examples of Shooter’s conflicts with his editors and creatives, and it would not be an understatement to say that there were few tears shed when Shooter was shown the door by upper management. On April 15, 1987, Shooter was fired, sending shockwaves through the comics industry.

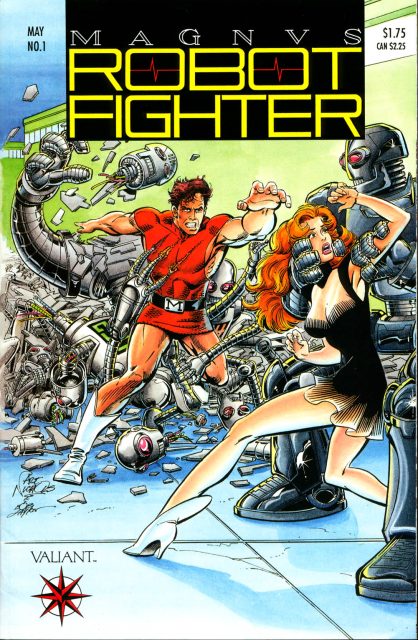

Shooter was down, but not out, and in 1989, backed by some deep-pocketed investors, he launched Valiant Comics, which featured characters and stories based on WWF wrestlers and Nintendo games for around two years. His next big move, two years later, was to revive several old-time Gold Key characters like Magnus, Robot Fighter and Solar, Man of the Atom, and got notable talent like artist Barry Windsor-Smith to work on the books. Interestingly, during his tenure at Valiant, as a cost-saving measure and sometimes to fill in for a penciler who was late, Shooter sometimes filled in using the pseudonym Paul Creddick. He expended his considerable talent to make Valiant a successful company, but was fired again in 1992.

Shooter refused to be consigned to the ashcan of comics history again, and bounced back in 1989 with a new company called Defiant Comics. Although Defiant’s first title, Plasm, was a hit, none of the company’s other comics — War Dancer, Dark Dominion, The Good Guys, etc. — made much of an impression on the comics-buying public and, some 13 months after its inception, Defiant was out of business.

Ever persistent, Shooter then joined forces with Broadway Video, the company that puts out Saturday Night Live, to publish Broadway Comics in 1995. However, when Golden Books purchased Broadway Comics, its handful of titles were cancelled in 1996.

Jim Shooter later went to Acclaim Comics to write Unity 2000, a series that endeavored to revive both new and old characters. Acclaim planned six issues, but went under after only three issues were published.

After this, Shooter drifted through the comics industry writing for a variety of independent comics, even returning to write The Legion of Superheroes again in 2007, some three-plus decades after he’d first written the title. He followed this up with scripts for Dark Horse Comics in 2007, reviving some Gold Key Comics characters like Magnus, Robot Fighter, The Mighty Samson, and Solar, but it seemed that the former clout he’d enjoyed at Marvel continued to elude him. In a recent Hollywood Reporter obituary, former DC President Paul Levitz said of his long-time friend and poker buddy, “He was far weaker as an enterprise leader, and unfortunately that was what he most wanted to be. His sense of history was not, in my view, as good as his sense of fiction. But what he did well, he did gloriously.”

Shooter stayed as active as he could after a string of failures, working both inside and outside of the comics business. He had his own blog, and continued appearing at comic book conventions, where he’d discuss the towering highs and debilitating lows he encountered in his quest to do comics his way.

One thing that’s not widely known about Shooter is that he frequently went to bat for creative talent, ensuring that they got higher page rates, were paid royalties, and got health insurance, even though the comics business has always been notoriously stingy about offering perks like that to creators. He did much good for many people, and often did it without getting any credit for his kindness and generosity. Shooter may have a complicated legacy, but there’s no doubt that he was a towering figure who never stopped trying to innovate and treat his freelancers decently. He deserves to be remembered with respect for his many positive accomplishments, no matter what his detractors said.

The post Jim Shooter, Sept. 27, 1951-June 30, 2025 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment