And then, like an obscure harbinger of some maddening unknown fate, Saga de Xam appeared on the translation scene. This might be the most famous of the early "graphic novels" not printed in the English language until now, though it had been widely read, or excerpted — looked at, at least — through digital scans of its 1967 first edition from Le Terrain vague, the longstanding project of adventurous publisher Éric Losfeld. It was by Losfeld's taste for provocation that comic albums for adults had become newly prominent in France: he published the first collection of Jean-Claude Forest's Barbarella in 1964, then Guy Peellaert & Pierre Bartier's The Adventures of Jodelle in 1966. Like those projects, Saga de Xam was named for its glamorous heroine and carried a strong erotic element. Unlike those projects, it was never pre-published in any magazine; it was a singular extravagance, priced at 60 francs with a tiny print run of 5,000 copies, never reissued in Losfeld's lifetime — in part because the expense was too much, but also because having a few desirable items that nobody can buy helps stoke interest in an outré publisher's wares.

This English edition is premised upon a 2022 French release from Éditions Revival, which was the book's first-ever color reprint. It is slightly smaller in proportion than the French edition, 10.25" x 13" vs. 10.75" x 14.5", and it omits most of a small gallery of bonus art, but it carries over an extensive introduction by the 2022 edition's editor, Christian Staebler, which presupposes that anybody purchasing Saga de Xam in the 2020s does not really need to be lectured on its good qualities. If anything, Staebler embraces ambivalence. The book's artist, Nicolas Devil, quoted from 2015, states candidly that his work "fell into a trap of which I'm now aware, that of aestheticism," his teeming ideas becoming "gratuitous." The book's scenarist, Jean Rollin, quoted from 2008, claims substantial involvement in only the first five of the book's seven chapters, by which point it was "losing some of its meaning, and it became hard to follow." Among the most critical voices is the most famous of the book's numerous guest artists, future Métal Hurlant co-founder Philippe Druillet, who expresses love and respect for Devil, while lamenting the book as a product of a "Parisian-intellectual-Losfeld ghetto... reserved for the hip intelligentsia." As a publication, an item, Saga de Xam is "directionless" and "high-society," abhorrent to comics' potential as inexpensive, accessible art for the masses - typified then by the rapidly liberalizing children's magazine Pilote and, one presumes, the later Hurlant.

Druillet then adds that he owns two copies of the book: one for his house and one for his studio. Despite it all, Saga de Xam cannot be denied. To insist upon itself is to speak for itself.

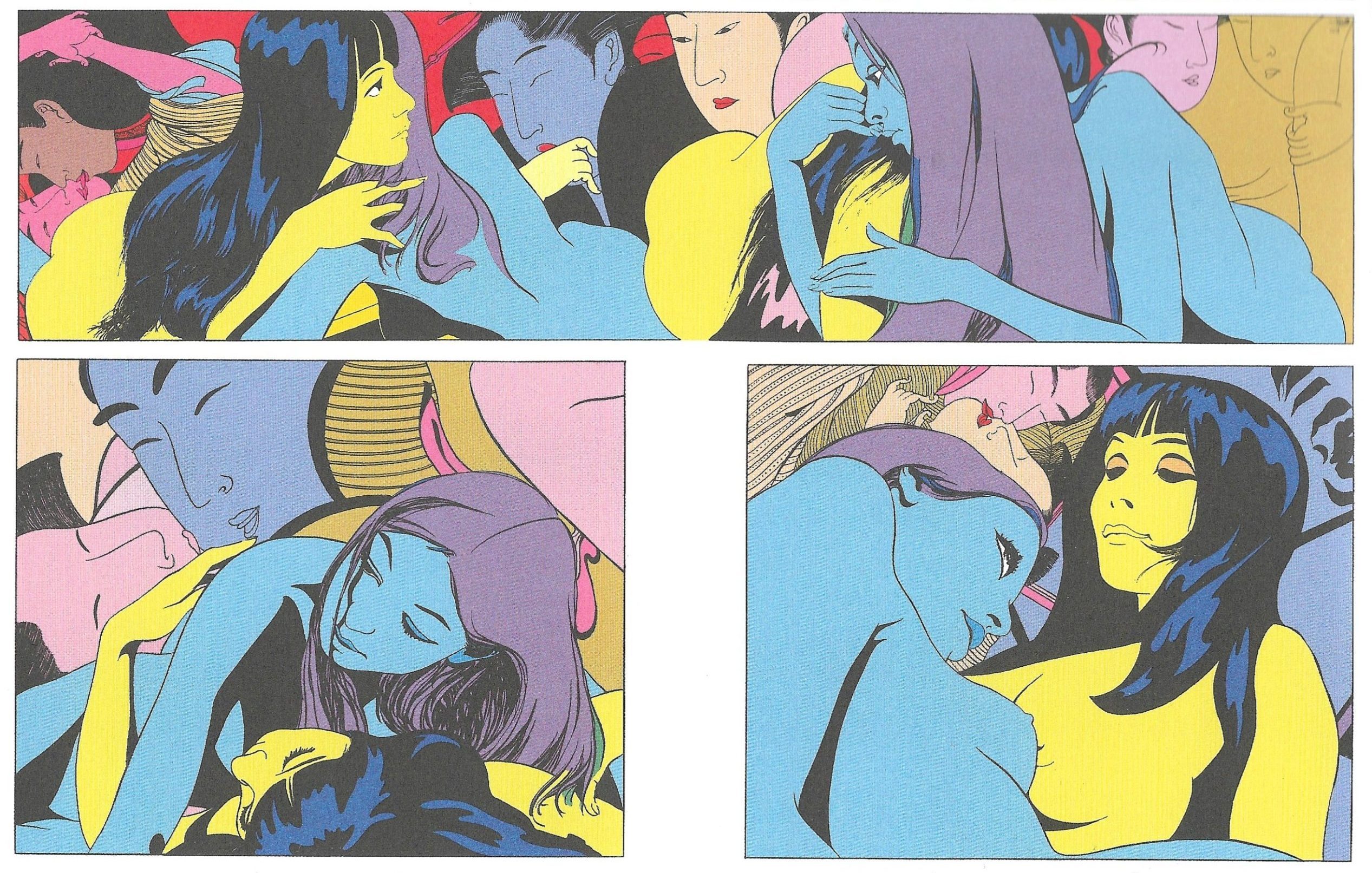

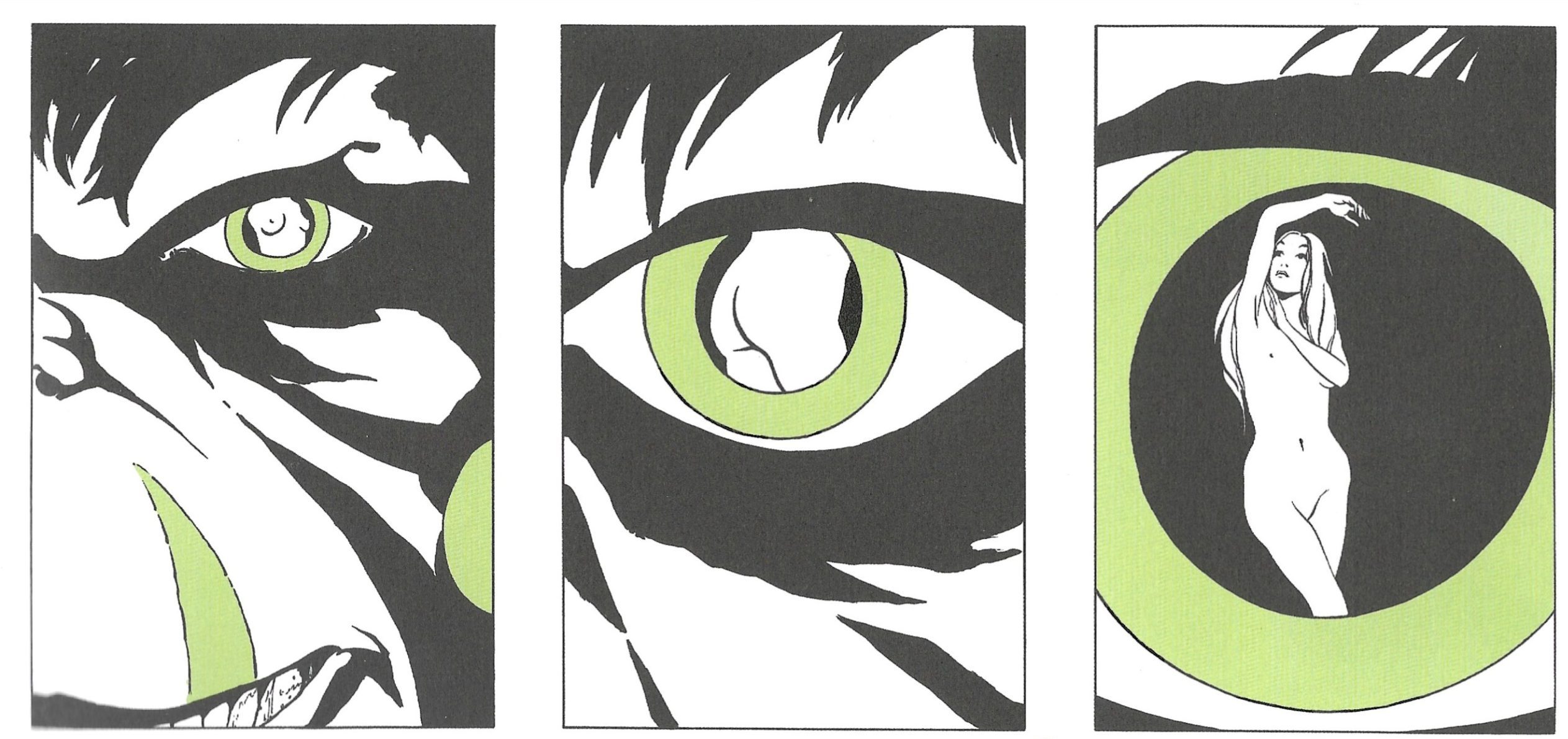

In case you are not familiar, Saga de Xam is the story of Saga, an emissary from Xam, which is an ancient civilization of women situated in a parallel dimension to ours. Observant of intelligence, beauty and love as their sacred virtues, the people of Xam are more or less immortal and reproduce only occasionally, through parthenogenesis. This has made for a socially rigid utopia: one ill-equipped to respond to unexpected disasters, such as all-out invasion by interstellar Troglodytes. The only option is to send a lone heroine, Saga, to "a strategic spatiotemporal point" (our world) to fire "a beam of catalyzed collective thought" that is supposed to cover Xam in an impregnable energy shield. Not everything goes according to plan. Flitting around the eras of human civilization, Saga falls in love with what she believes is an Earth woman, but is actually the folkloric Mélusine, a fairy associated with carnality, fertility and shape-shifting. Saga too changes shape, adopting irrational, passionate human characteristics through her adventures, leading to a climactic encounter with the Trogs on Xam, who both are and are not as destructive a force as they first seem.

Before images were easy to load online, this comic was most prominent in English-speaking terrains as a footnote in the oeuvre of its scenarist, Rollin, who became prominent as a director of hypnogogic fantasy films almost immediately after the book was first published. Though frequently ridiculed in France during his most active period, 1968-1984, the extreme specificity of Rollin's films — it would be glib but not wholly inaccurate to say they are typified by women in striking outfits walking around a lot — put them at the front of the line when international horror and "cult" movie enthusiasts sought to reevaluate European auteurs. You cannot mistake Rollin's films for anything else. They often employ the devices of horror movies, but remain noncommittal towards scaring the viewer or (for the most part) grossing them out with gore. They are overwhelmingly "sexual," in that they are filled with nude women, hypnotic suggestions, mysterious compulsions, and an intensely fetishistic atmosphere of repetition, yet "sex" seems to function as predominantly an aesthetic mode; the prosaic act of fucking feels banal, even perplexing in Rollin's films.1 It also didn't hurt that Rollin himself was thoroughly educated in art history, and could provide disquisition on his own work when needed. This was not a formal education. Rather, his mother was active in the greater Parisian cultural scene between the world wars, and as he grew, Rollin cultivated a familiarity around artists and intellectuals.

As a result, by the mid-1960s Rollin already knew both Éric Losfeld — having attended various get-togethers at Losfeld's bookstore, also called Le Terrain vague — and Nicolas Devil, who had supplied drawings for one of Rollin's early short films, 1965's Le pays loin, put together on off-days while Rollin toiled as a sound editor for a newsreel company. Devil's situation was different. He was born Nicolas Deville, into a well-to-do family of colonists in what was then French Indochina. By the '60s he was living in Paris in an enormous property belonging to his father, which became a popular spot for congregating bohemians. It was Rollin, an admirer of American adventure strips like Tim Tyler's Luck and Mandrake the Magician, alongside French comics of his youth, like Fantax, who suggested Devil propose an album to Losfeld along the lines of Barbarella. It took two years to make, after which Devil began to focus on illustration; he was the primary author of a collaborative book in 1974, a compendium of copyright-free texts, graphics and comics titled Orejona, which was followed by other, more traditional illustrated prose collaborations before his withdrawal from the visual arts to teach philosophy in Quebec.

This is another way Saga de Xam is a monolith. It was not only the first, but the only traditional longform comic by either of its principal creators.

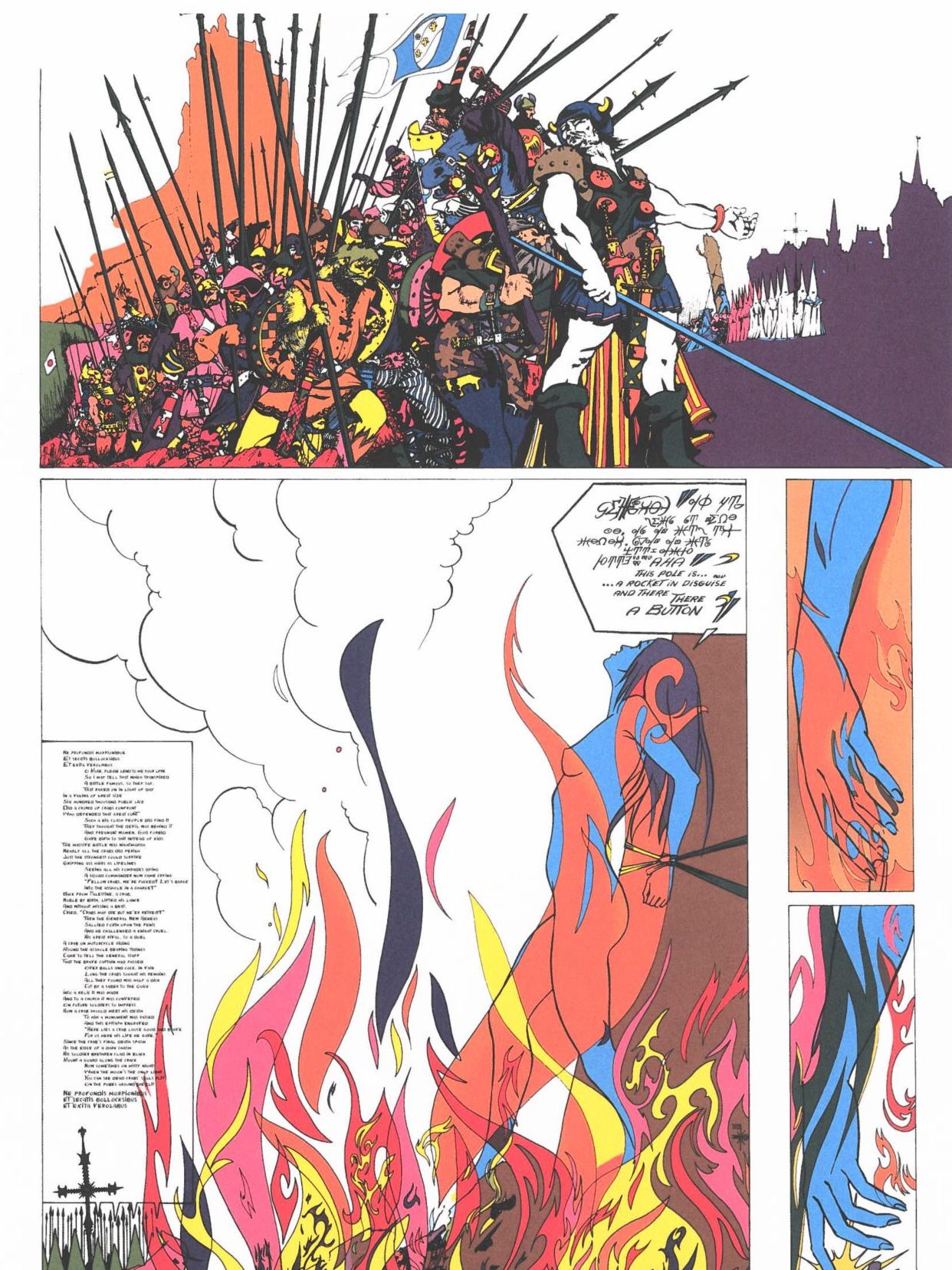

The risk of a project like this is a superficial and dilettantish reliance on novelty, but what transpires is more an acute sense of the artist thinking everything through. Devil organizes each page as a self-contained work of design; I don't think a single layout is repeated throughout the entire book. As a result, the narrative rhythm is often contained by the parameters of the page, reset at the top of the next. But there is no reiteration of the story, as would be expected of a serial. The plot instead plays out briskly across a multitude of restarts, so that the reader senses the artist perpetually reconsidering their approach. Adding to the self-awareness, early chapters riff on classic adventure comic settings: medieval swordplay a la Prince Valiant; captivity and mutiny on the high seas; a visit to prehistory, where amusing parallels are draw between a tribe of early men and the Smurfs. Saga saunters across these pages with bemused indifference, like a lapsed comics reader gazing upon juvenilia with adult eyes. But before long, she is drawn back in, affected against her better judgment by the enormity of the emotions coaxed from her. A pair of fellow emissaries from Xan appear, named after Barbarella and Jodelle. "Those two are driving me crazy," Saga laments, "all stuck up because they have one little stone to lay."

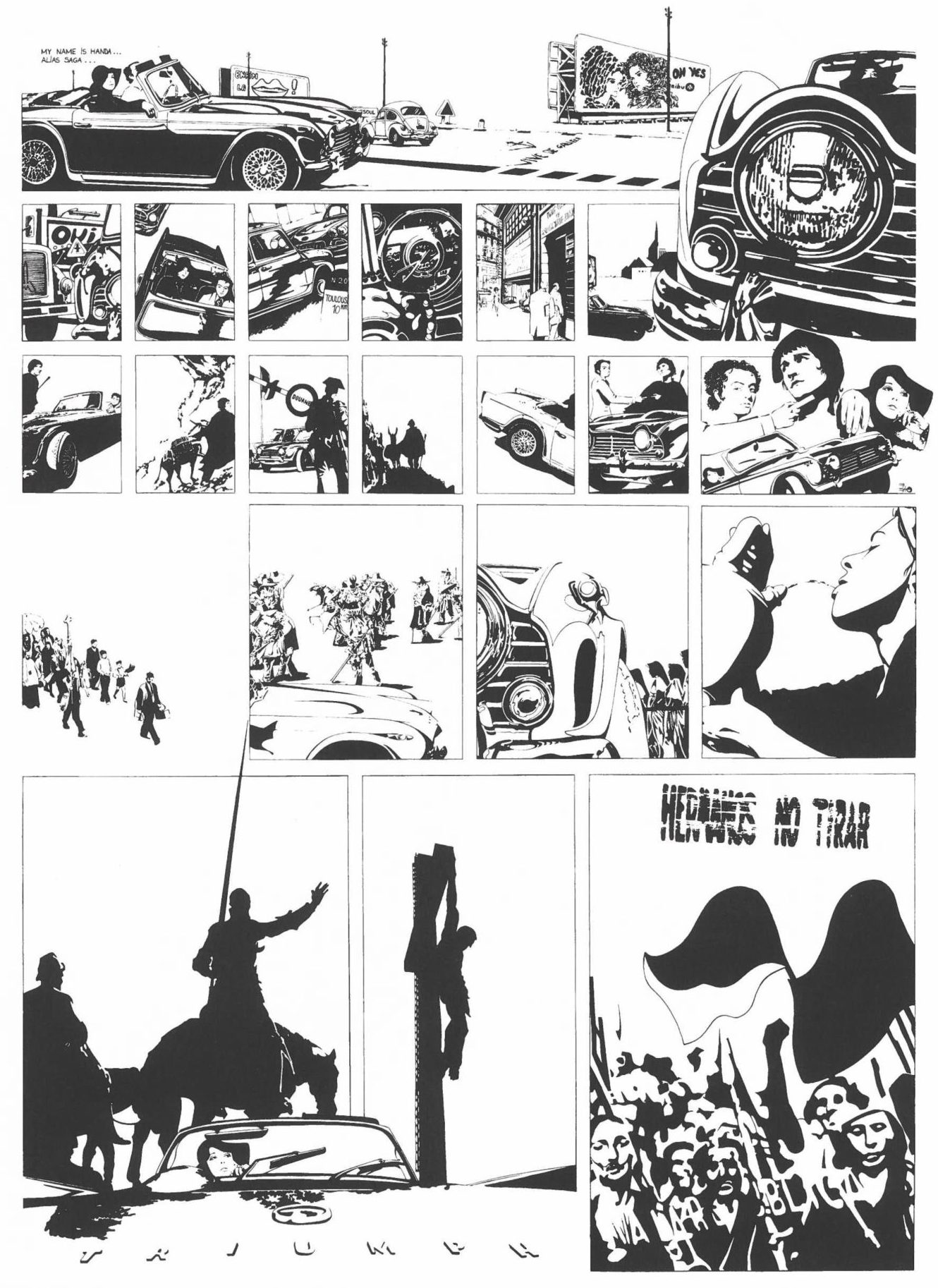

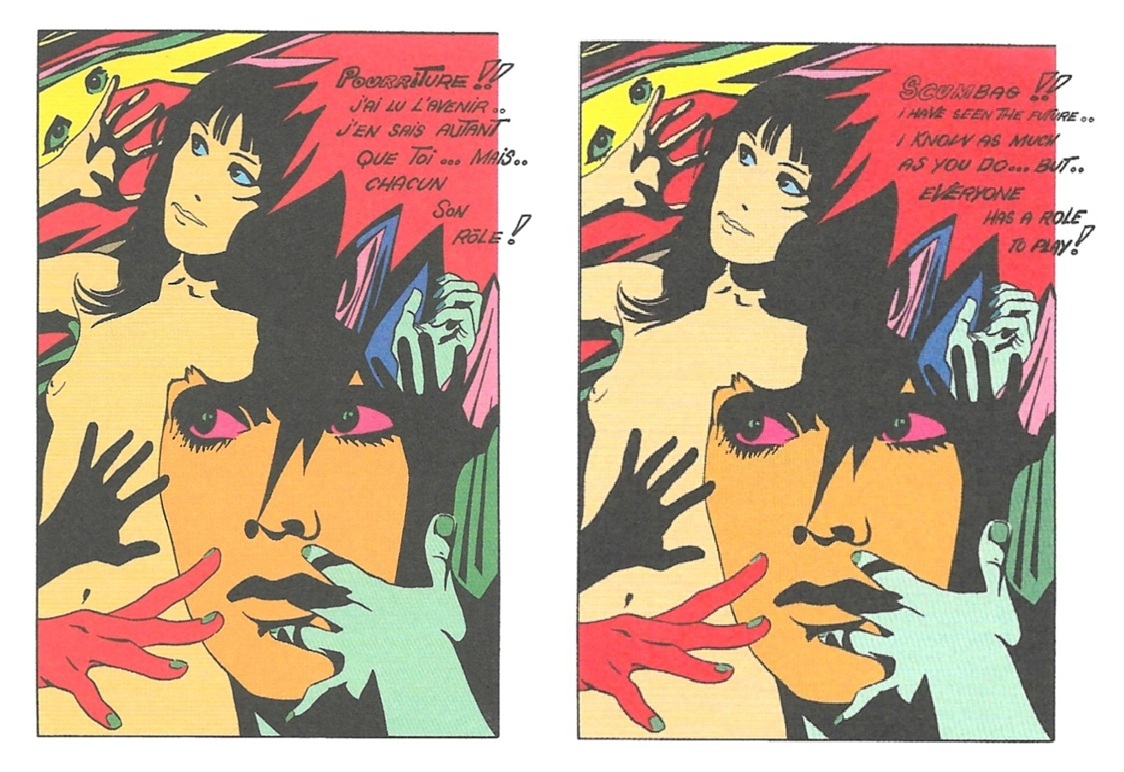

By this point, four chapters in, Devil has begun modifying his style to broadly approximate narrative art from Ancient Egypt and China, dictated by where Saga has landed. You might draw a line from him to an artist like J.H. Williams III, but Rollin is not an Alan Moore supplying thorough scripts; all of the art and dialogue, everything on the page, is credited to Devil, who should be understood as adapting Rollin's scenario to the comics form. At the same time, Devil was not alone in his big house — four guest artists are credited with chapter headings and "exquisite corpse" jam pages, along with three colorists and an extraordinary 98-person list of reference models: some of them fictional characters and celebrities presumably copied from books or magazines or LP covers, but others drawn from people just hanging around Devil's studio.2 Much of the collaborative action happens in the seventh and final chapter, in which the bubble universe seems to pop, pages erupting into b&w cut-ups and collages of late '60s cultural/consumer signifiers, and then a riot of color splashes meant to convey the effect of LSD.

There are comparisons that can be drawn with other subcultural comics of the time, even setting aside the earlier Losfeld books. The mind races to Italy and Guido Crepax, working in a similarly rarefied venue — the trailblazing adult-targeted comics magazine linus — cultivating his taste for unorthodox page layouts and saucy heroines. Guido Buzzelli first published The Revolt of the Wretched ("La rivolta dei racchi") the same year as Saga de Xam, in conjunction with the Salone Internazionale dei Comics, to a very limited readership; that story also evoked adventure comic visual dynamics to satirical ends. At times I found myself recalling Jack Jackson's Conan the Barbarian parody, "Testicles the Tautologist," from 1973's Skull Comics #3, in the grotesque zeal with which Devil draws action and violence, although the sexuality is not as neurotic as it tends to be in the American undergrounds; it is brazen, a little calculated. In the early chapters, Saga is often being captured, stripped nude and abused, but remains unflappable, to a dual purpose — a sexy, invincible goddess who is still periodically molested only sweetens the reader's daydream of conquest. Staebler suggests that the "human brutality" early on in the book may be Devil's means of accommodating Losfeld's editorial demands for licentious marketability. Regardless, any such exquisite balances have faded in a matter of pages, because Devil can't seem to abide paying that much attention to human men. He and Rollin are alike in that way.3

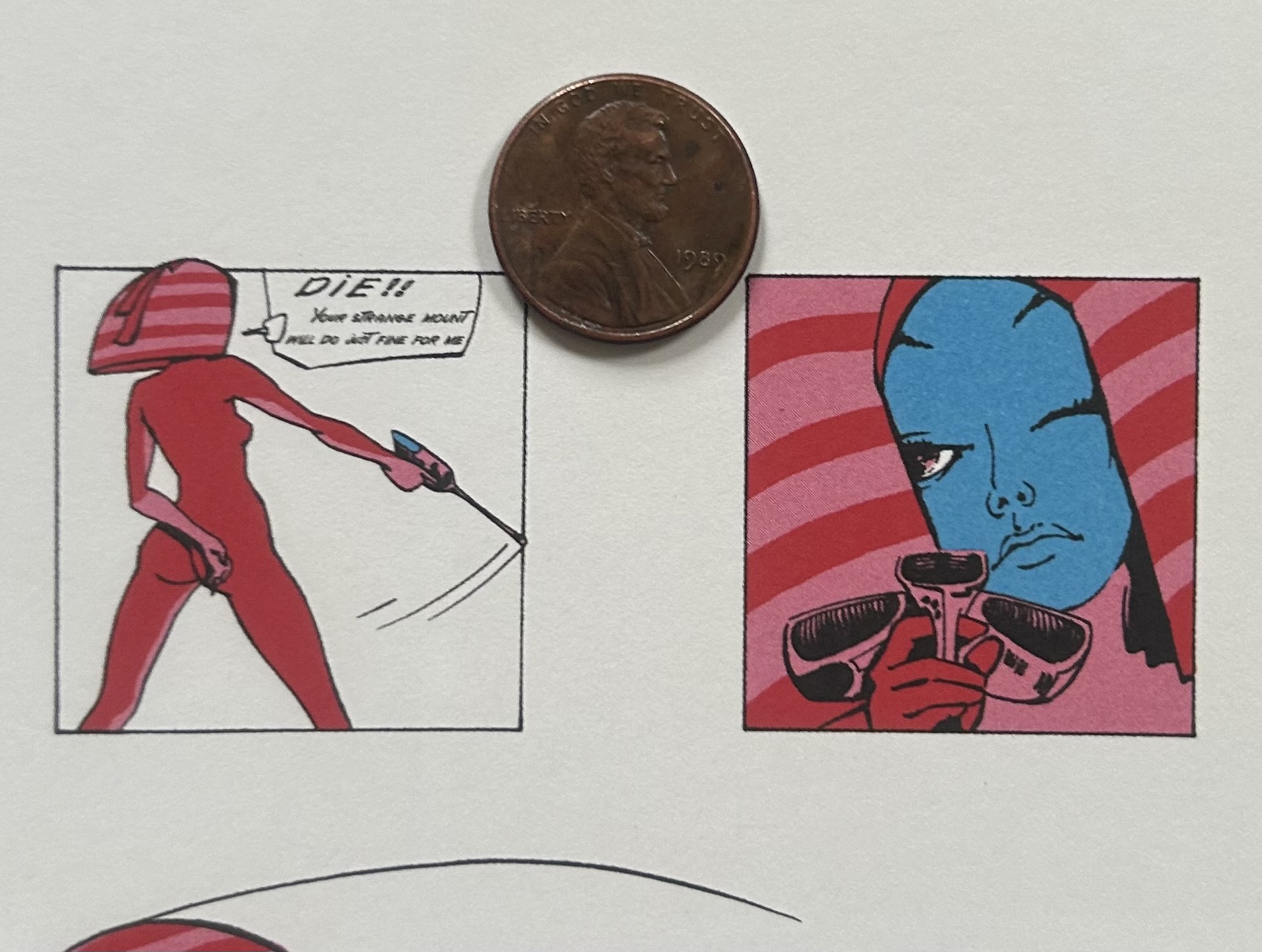

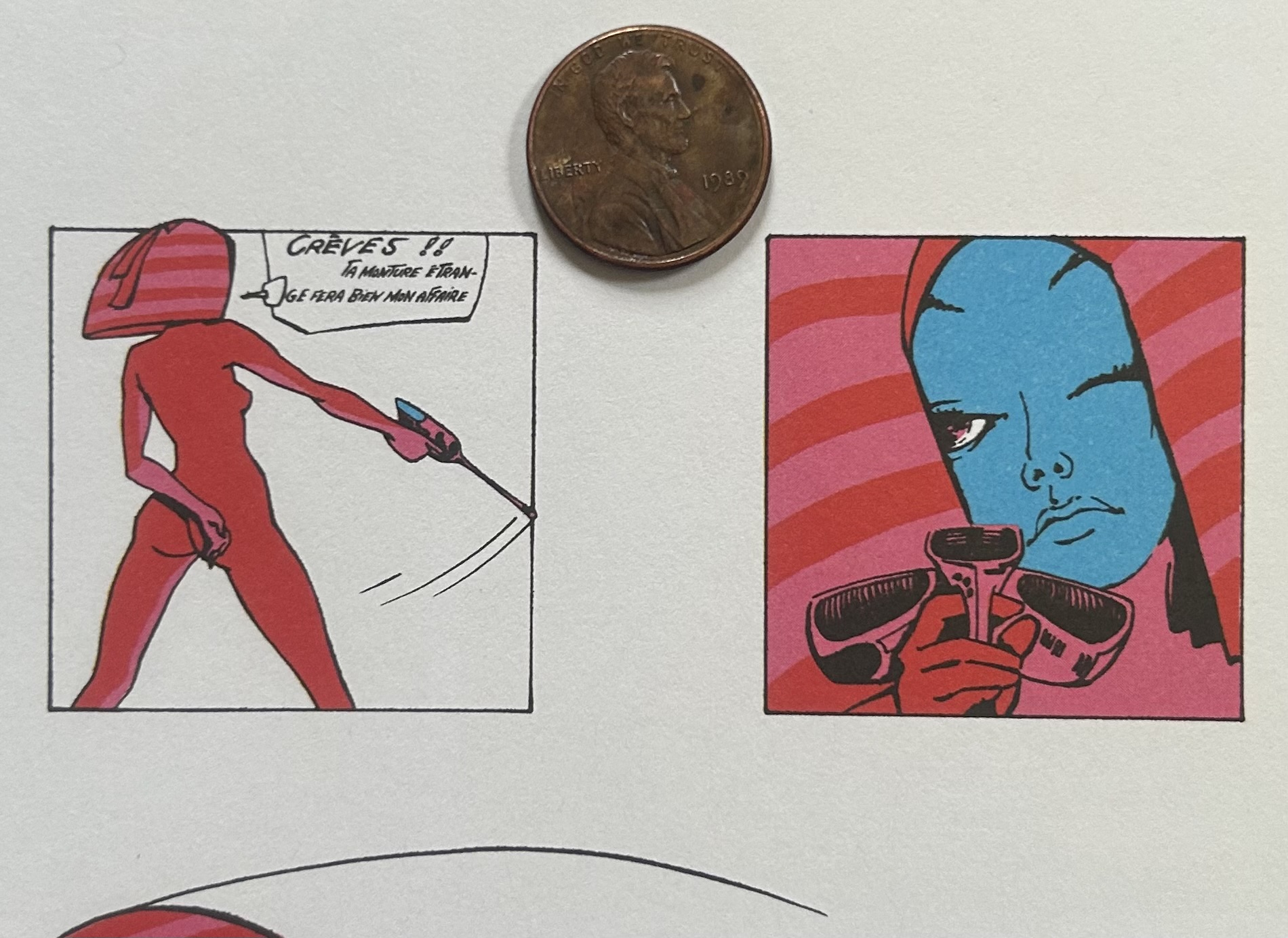

But if you have read Saga de Xam already, there may be another question on your mind: how, exactly, would an English translation even function? Devil's lettering is integral to the visual harmony of the page in a more self-evident manner than usual in comics — parts of the dialogue are written in French, while parts are drawn out in a series of graphic dialects of Devil's own design, hewn from the same contours as his character drawing. Furthermore, Saga de Xam is famously difficult to read on a physical level; Devil drew the book at 30" x 42" and either did not consider or deliberately ignored how the art would shrink down, leaving some of the word balloons so tiny that the reader must press their nose against the page to make out what is being said. Copies of the 1967 edition came with a small magnifying glass to alleviate this problem, but no such assistance is available now; ironically, this reinforces the idea of the lettering as integral to the art, because the tininess of the word balloons discourages the reader from thinking that every line is necessary to read, positioning them as purely graphic flourishes.

The solution hit upon by the English edition is to observe absolute obedience to Nicolas Devil. The credited letterer is Maura Murnane — working from a translation by Anna Bialostosky — who not only matches the style of Devil's French lettering very closely, but reorganizes his fantasy lettering so that its characters translate into English words rather than French. (A translation key is provided in the back of the book for this purpose.) When Devil's lettering is unreadably small, the font size of the English lettering is reduced to similarly onerous proportions. "But that isn't a substantive quality of the work!" the pragmatic reader cries. "It's a fucking mistake!" Yet the ideology of this translation is that any quality of the original is a substantive quality, and must be preserved. In one panel, where Devil appears to have accidentally let his letters drift outside the borders, the English edition obediently repeats the mistake. A small amount of the text in the original was presented in English — those portions are left as-is, without correction of grammatical errors. In a particularly inspired touch, the very last block of lettering in the book, which is drawn by Druillet (rather than Devil) in an extremely decorative and calligraphic style, is left completely untranslated on the page, and is then presented in English as a text afterword, a final statement on the translation.

It's funny, because like most contemporary reprints of older comics, this Saga de Xam is a fiction. It doesn't replicate any of the mechanical processes that created the 1967 book, because it can't; the materials are long gone. Staebler explains that the 2022 color reprint used a 1980 b&w reissue as its source, which was digitally repaired and re-colored by Staebler and Devil's son, Stanislas Deville, with the aim of replicating the original's qualities as closely as possible. I am not one of the lucky 5,000 to own a copy of the '67 edition, so I can't offer comment on how well they succeeded. I am one of the many that only knew this book as a digital upload, which is its own type of fiction. But in the midst of these uncertainties, the choice is made to serve the monolith, as if we must cry now that art is not only clay to be molded and remolded. If Saga de Xam does not exist, it must be invented.

Inevitably, we end on a testament to an uncertain future. For all its commune hippie flamboyance, the book is not especially optimistic. The society of Xam is eugenicist, its complacency prone to labeling refugees as invaders. In the ameboid figure of the Troglodyte we catch a hint of anxiety about the arrival of foreign contagion, an irresistible transformation of the majority, Les Schtroumpfs noirs. Or, sense angst about gender relations, with feminine Xam and the masculine Trogs as physical incompatibilities, solitudes incapable of meaningful production. And when the revolution comes with Saga, it is violent: in the distance we see the upheavals of May '68; the Years of Lead; Hell's Angels at Altamont. We are bracing for disaster and denied our pathos, because to build anything new, Devil suggests, is to destroy everything completely. His book didn't do that, but such are ideals at the dawn of the new thing.

* * *

The post Saga de Xam appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment