Much like the overnight success they experienced upon launching their podcast nearly a decade ago, Chapo Trap House’s entry into the Comics space comes by way of opportunity, rather than ambition. Debuting amid the harrowing 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, early iterations of the podcast were anathema to disillusioned Obama supporters whose vision of the hope and change he promised was much further to the left than the middling policies and status quo positions he actually delivered, especially as they saw more of the same on the horizon with the next crop of Democratic candidates.

Among a slew of targets, Chapo Trap House took aim at the the mediocre strivers of the professional-managerial class with a bilious wit that split the difference between the spit-flecked, Gonzo dangerousness of Hunter S. Thompson and the unsettlingly wonkish timeliness of the Capitol Steps; not cool, of course, but very, very funny. Much of their ire was reserved for the terminally online culture warriors of the right, working fanatically to launder their crankish ideas into mainstream discourse with assists from the cognoscenti at journalistic institutions like the New York Times and paychecks from a coterie of Right Wing think tanks. But it was the Democratic party for whom they reserved their most potent venom, sizing them up as hopelessly out of touch on a good day and given to ratfucking when the centrist ecosystem they sought to cultivate was threatened. In presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders, Chapo Trap House found the best representation of the democratic socialist values they hoped to enact and championed his campaign while providing a platform for similarly motivated journalists, activists, and provocateurs. They aren’t leaders. They didn’t spur a movement or anything like that, but they did play a role in encapsulating a moment. It wasn’t enough, of course, and you know the rest.

In the intervening years, the world has gotten worse and the politicians stranger, but the progressive politics of Chapo Trap House’s mostly static line-up have remained the same. No longer such an outlier, they now reside among a constellation of like-minded media projects across a multitude of platforms. For good or ill, to the frustration of fans and critics alike, they have evaded the para-social pitfalls that plague other content creators by revealing the bare minimum when it comes to behind-the-scenes machinations and controversies, asking neither permission nor forgiveness.

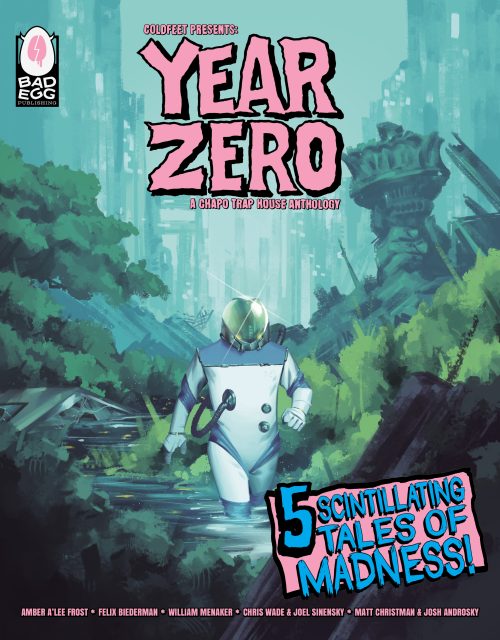

Like every success story in American media, all roads lead to the formation of a production company and Chapo Trap House is no exception. Their new comics anthology, Year Zero, arrives in partnership with Bad Egg Publishing—a relatively new venture from YouTuber and streaming personality Charlie “Moistcritikal” White—and aims to highlight their chops in the realm of scripted entertainment. As a first outing, Year Zero is better than it has a right to be, owing to the trust its creators have placed in the hands of the industry professionals who are executing their conceits. Even at its premium price point, Chapo Trap House listeners will be pleased to find stories that embody the podcasters’ senses of humor, aesthetic, and historicity. For everyone else, Year Zero bears all the hallmarks of the political comics anthologies that preceded it, though its allegorical genre register cuts closer to Slow Death or Ex.Mag than the polemics of World War 3 Illustrated. Whether Comics is a waypoint for Chapo Trap House or a more permanent venue for further endeavors remains to be seen, but it’s clear that they recognize the potential of the medium. I spoke to podcast co-host Will Menaker about the project in Mid-July.

- Ian Thomas

Photo Credit: Laura June Kirsch

IAN THOMAS: Am I correct that you're the biggest comics fan in the group?

WILL MENAKER: Yeah, I would say that is probably the correct assessment. I think working on this comic book, writing my first comic book, is sort of a coming home for me in a number of respects because I was a huge comic book fan when I was a kid. I would go to the comic store Big Apple Comics on the Upper West Side every week. I was a big fan of the Jim Lee era of the X-men, and stuff like Spawn. I've always really liked comic books. I remember finding a huge cache of my dad's old comic books and Mad magazines and stuff and just leafing through those. As a kid, I wanted to draw comics, that was like my first career dream.

And later, I had a career before podcasting. I was an editor at a New York publishing house and I worked on a number of graphic novels for Liveright|W.W. Norton. I got to work with some of the very big names in graphic novels like Robert Crumb, Jules Feiffer, and, eventually, Alan Moore. I acquired the American rights to his novel Jerusalem.

Are you familiar enough with industry history to have any favorite reactionary cranks of the type you often discuss on the show?

Oh, well sure. I mean Frank Miller at various points in his career would certainly fit that mold and I’ve got to say I'm a big Frank Miller fan. I don't know if I would label him as, holistically, a reactionary crank, but the DNA of that is in his work. I think he had more of a post-9/11 Right-Wing turn. I think he's maybe turned the corner on that, but I've always been a Frank Miller fan.

Maybe I’m over-intellectualizing it, but I see podcasting and comics as generally populist forms of media. Do you think in those kinds of terms as you approach new projects?

Maybe not only explicitly in those terms. I don't think you're wrong, though. I think it's a populist medium in so much as it's a narrative form in which the combination of writing and art really makes it so, if you're writing it, your imagination is unbound. You're constrained only by what the artist is capable of rendering, which is anything. So, as opposed to television or film production, which requires a ton of money to create something fantastic or even to show something like a period setting is just so prohibitively expensive that only so much will get made. There's only so much you can do with that. I think comics is a populist medium in that it is more accessible. The imagination and the creativity of the artist and the writer is less constrained by money.

Do you see comics’ incursion on Pop Culture—as in the success of superhero cinema stuff, for example—as having an effect on the kind of comics people are making? Do you think when creators see that kind of success they are tempted to see comics as an intermediary step or a proof-of-concept step for something more lucrative or further reaching?

When something becomes culturally hegemonic, in terms of the money behind it, as we're seeing now with superhero stuff, I think it creates a knock-on effect where people are just sort of copying or chasing the last thing that was successful. So, it creates this Xerox effect where I think it crowds out —even in the comic book genre, even in the superhero format—the opportunity for an original take, or something that is different than what you've seen before. It becomes a little homogeneous because I think, once again, it goes back to the amount of money that you have to invest to create a comic book movie and then how much money it has to make to be profitable. I think that leads to creative decisions that are more constrained.

Can you talk about the genesis of Year Zero?

Well, Chapo Trap House started our production company and a guy who was helping us with that, Dan Dominguez, put us in touch with Bad Egg, the publisher. They approached us with this idea for a Chapo Trap House comics anthology and we all thought it was a great idea from the start. We've been writing stuff for TV and movies and trying to get that off the ground and this is an opportunity, like I said, to be unbound and let our imaginations dictate the pace, dictate the terms of things, and have something real in people's hands they can see and read and enjoy, on a much shorter timeline, in a format where we could really do whatever we wanted.

Anthologies, especially as introductions go, have a lot going for them, but they can be hit or miss. Can you point to any anthology concepts from which you drew inspiration for Year Zero?

Well, when they first said anthology, the thing that came to my mind was Tales from the Crypt and the whole EC Comics era.

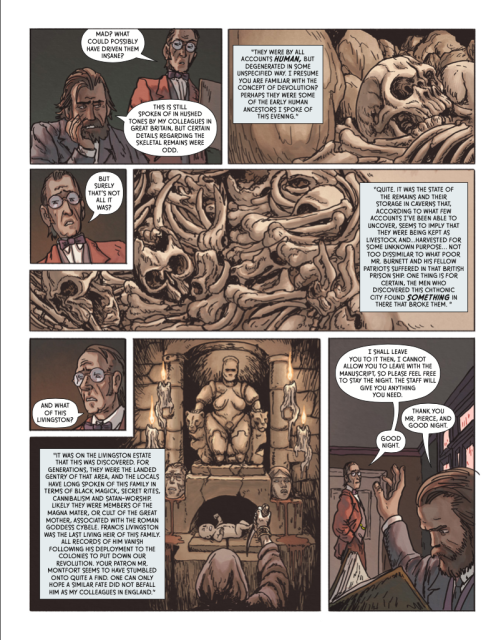

I love the comic book Tales from the Crypt and I also love the TV show Tales from the Crypt. Similarly, I have always been a huge fan of anthology television series like The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits. I think all these stories—at least mine—I was heavily borrowing from that sort of tradition of weird fiction. Again, [it’s] the freedom of creativity that you have in telling a one-off, discrete story. It doesn't have to go on and continue and can just be self-contained. You can just do one thing, tell one story, and then next week it's another story.

What makes genre storytelling so suited to the subject matter associated with Chapo Trap House?

The humor and universe of the show draws from the news, but the way we understand it, the way we talk about it, builds to a constellation of references. But also the absurd and grotesque hyperbole and satire and exaggeration that we do as a form of political humor, I think, lends itself very handily to genres like horror or science fiction or fantasy.

By the same token, when genre stories fall short, it’s often because they may be addressing their themes too directly and ring false. As you’ve entered into this mode of storytelling, what challenges have you seen? What is your sounding board and how do you avoid those pitfalls?

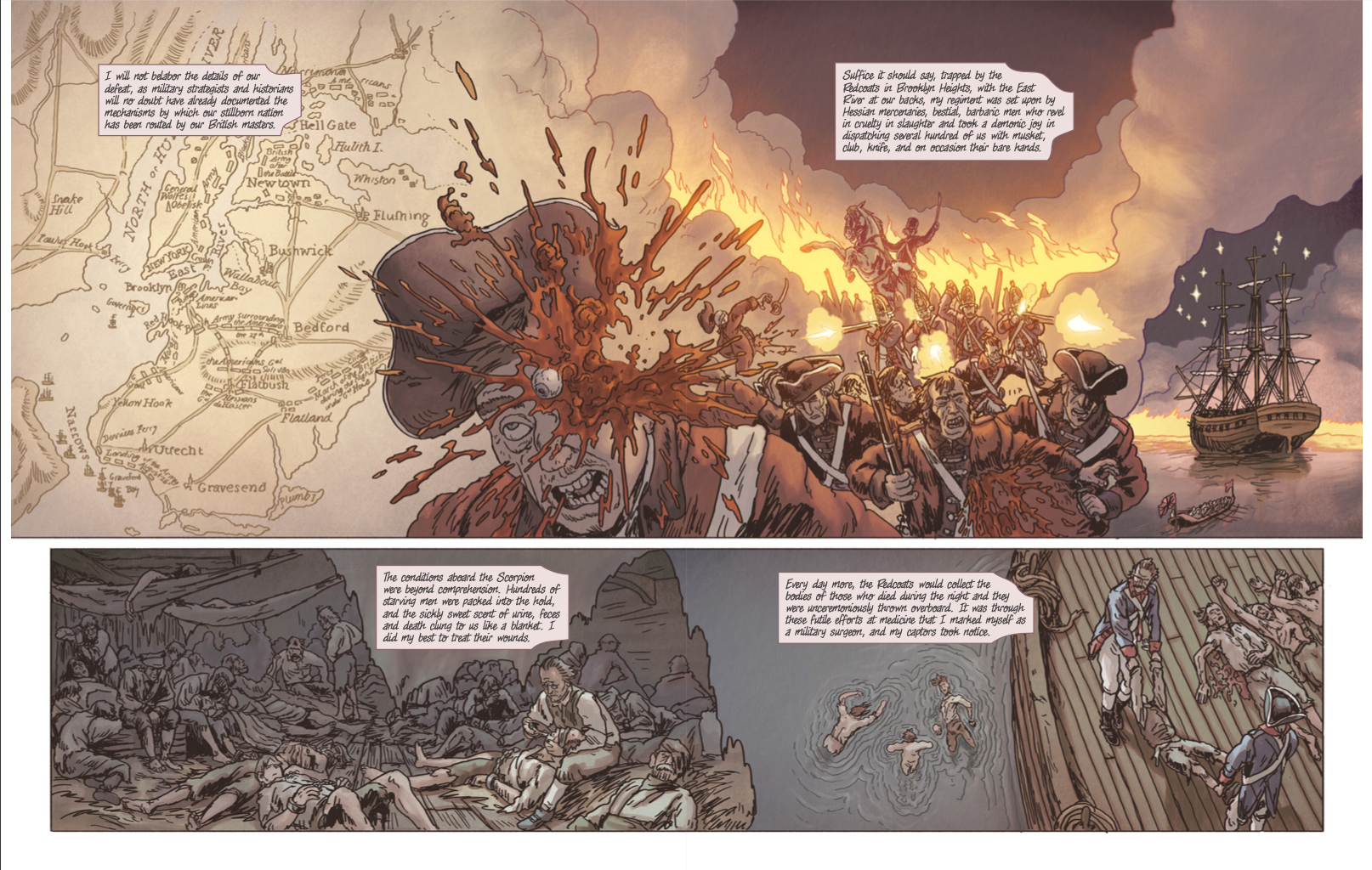

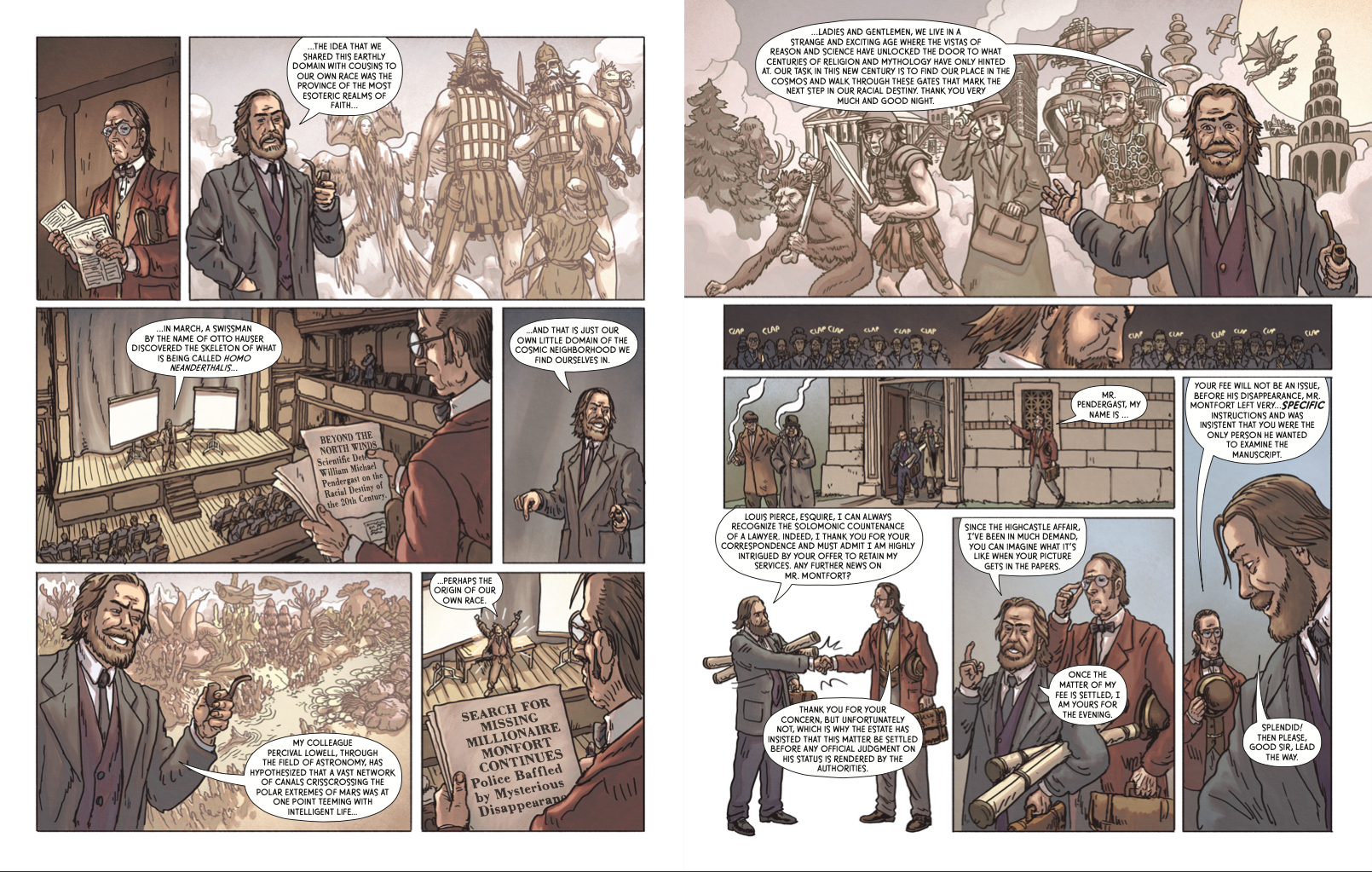

I definitely agree with you. Our North Star for all of these was to create, like, five great individual comic books over like a six-issue arc that were genre-focussed, which would inevitably be in some way touched by our personalities. Our political points of view are certainly a part, but there's nothing didactic or like Schoolhouse Rock. Felix [Biederman]’s story obviously features real political figures throughout American history in a bizarre action movie science-fiction convention. I believe the opening scene is a clone of George H.W. Bush shooting George H.W. Bush. Obviously, fans of Chapo Trap House are going to see our DNA in these stories. Speaking for myself, I just wanted to do my version of an H.P. Lovecraft story. That’s, for me, what came first.

And these stories are meant to stand on their own? If so, does that preclude using them as proofs of concept for other things down the line?

No, not at all. This is obviously to give something to our fan base, but my real goal is that I would love for fans of comics to discover this on their own and, not knowing anything about the show, or our politics, or any reference to who we are, or what our show is about, to just enjoy what are five beautifully, beautifully drawn and really original, weird, cool stories.

If I understand correctly, your relationship with folks like Simon Roy, for example, preceded this project. Beyond the art, did those relationships give you some insights into navigating the industry standards and the production processes associated with comics?

As far as Simon, he did a couple of posters for us. Simon is a guy who I had been a huge fan of his work, before I even started doing Chapo. The first time I became aware of him was when Image rebooted the Prophet series.

I saw samples of it online and I knew I just had to buy that comic. I bought every issue of that comic because the art was incredible, but also the science fiction universe they created was so unique and so original that I was just a die-hard fan. When I started writing this story in my head, what I was seeing was Simon’s art. He was really my moonshot ask, the guy who would be my number one choice to draw this. I could not be more thrilled that he was available and the work he's done on it is spectacular.

I don't know if my awareness of comics, or having previously commissioned Simon to do work for us had quite prepared me because this is the first actual comic book I've written. Like I said, we've written stuff for TV and movies, like screenplays and pilots and stuff like that. For me, the learning curve to doing this was having to figure out that you can’t write a script to a comic book like you do a [TV or film] script. You can’t rely on a director to fill in how they're going to place each piece of dialogue in a panel. You can't leave it up to the artist because they need more direction. And what I appreciated about the process was sort of learning how to write as a director. You need to be a writer and a director at the same time and you have to be very specific about what takes place in each panel and how you move from one panel to the other and how much, not just dialogue, but visual information, needs to be included in each individual panel. That was the learning curve that I had to acclimate myself to when writing this project,

You're running this as a pre-order and the price point is about forty-five dollars for just over a hundred pages. It’s a little high for the space, but I expect that is to ensure that all your collaborators are paid fairly. It seems to be priced as a boutique or specialty item. You have passionate fans who, I'm sure, will be happy to have this. But what are your thoughts on expanding your work into more mainstream channels? I guess I'm asking, as you push past the boundaries of podcasting and online content creation, how you make the decisions around factors like cost and reach and stuff along those lines. In this case, are you putting those decisions in the hands of Bad Egg, the publisher?

My consideration is that I want the actual, physical book, itself, to be as top quality as possible. This is going to be in a magazine format, so oversized. There are going to be three volumes and then they will be collected into one Omnibus Edition at the end. For me, it's just a matter of the art and then the physical package to be as quality as possible. So, yeah, forty-five dollars for a comic, but it's not just a single issue of a comic, each issue has five stories. I can understand someone perhaps thinking that's a little steep, but it's the printing and manufacturing, as well as paying everyone. I think the package we’re putting out is pretty sweet.

Was Matt Christman’s Spanish Civil War book, ¡No Pasaran!, Chapo Trap House’s first foray into this pre-order model of publishing?

We'd already done a book through traditional publishing [The Chapo Guide to Revolution, Simon and Schuster, 2018], but the pre-order model for Matt’s book was really fantastically successful for us. We have an audience that we can directly communicate with and who are interested in whatever content that we have, so I think the pre-order model is a good way. You don't have to gamble.

I would imagine it takes a lot of the anxiety out of the process.

Yeah.

With Chapo Trap House, you’ve built something that functions in parallel to traditional marketing channels. What are the pros and cons of that as you see it? On a bad day when you are not happy with how things are, what do you see as the greener grass on the other side of the fence? Does that question make sense?

It would make sense, except I'm happy every day and I’ve never experienced a moment’s anxiety or dissatisfaction ever. [Laughs] I don't quite know how to answer. To me, I love doing the show. The show is our bread and butter and it is still very fun for me to do the show. I'm very glad that people still like it. I guess my grass-is-greener is for another variety of grass. We've always been interested in movies, comics, other narrative and creative fields in which we can take a shot at it. I'm not saying I always had the ambition to do a comic or write a screenplay, but the thought was always in there. The mental hurdle was that I'd never done it before. How could I really do that? How does one even begin? The good thing about the show is that it has opened up opportunities for us to just say “Hey, why don't we just do it?” and have a reason to do it.

I suspect it's probably different for each of you, but when you initially conceived of Chapo Trap House, did you conceive of it as a political project with political goals? Did you initially conceive of it as simply a show, as in a piece of entertainment? What do you want from it and what constitutes success?

What constitutes success is that we can support ourselves doing a creative endeavor that we are 100% in control of. We don't have a boss. Our boss is our subscribers. That is success for me. We still do the show that we want to do and we have a fan base that connects to that. Because of that, we have opportunities to do really cool stuff like work with Bad Egg or like me working with Simon Roy on this comic. As far as political success, I don't judge the show’s success. We have political opinions. I have, certainly, many things that I would regard as political successes in this country that are a long long way off from coming to fruition.

We have supported candidates before on the show. We've had Zohran on the show. I was very happy to see him win the mayoral primary here in New York City. But, I can't get into the trap of thinking of the show's success or failure in terms of building a political movement or building actual power.

It is still entertainment, we do a talk show about the news that is influenced by our political opinions. But those opinions and the medium in which we do it doesn’t really have agency. It has a power to speak to things that like-minded people, maybe, are not feeling like are being spoken to, in terms of the media they consume. That's not political agency. I think it's beneficial in some regards, if, for nothing else, just the morale of the individual, but I don't think the show can be understood as a political project. I mean, I think that there are political effects. I think we have wedged the door open a little bit in terms of the left of Liberal, or Socialist, or however you want to call it political consciousness, we didn't create, we were just sort of speaking to. I think a lot of people our age in this country feel not represented by anything that they see in politics or in the news media. This may be a beginning, but that's not political agency. There needs to be a party. There needs to be a container to hold and build upon that political point of view to direct it in some way.

Do you think that people look to Chapo Trap House to be movement makers and you have to push back against that?

No. I think a lot of times the people who believe that we're movement makers are the critics of the show because they think that we are just these rude podcasters—“their obstinance and obnoxiousness are what's turning people off from mainstream politics.” I think that's putting the cart before the horse. I think we're just speaking of the things that we feel and believe and it just so happens a lot of other people feel that way, as well. It's mostly critics of the show that are obsessed with the idea that we are movement makers or a political machine of some kind.

Chapo Trap House came about at the height of Twitter’s reach and popularity, nearly a decade ago. Those early shows were really honing in on a lot of the freaks and creeps of that ecosystem. Do you think the freaks and creeps of today are much different between then and now?

Like war, freaks always remain the same. The face of the American crank and freak largely remains unchanged and the only thing that's different now is that, as far as Twitter or X, the everything app, is concerned, they now have a Habitrail that's personally coded and conditioned to gratify their delusions. If anything, I think the freaks have gotten more mainstream and become organs and social media and communication and [have] become even more of an effective delusion simulator and amplifier.

On the relationship Chapo Trap House has with elected officials that are typically counted as part of the political spectrum you occupy, you’ve expressed dissatisfaction with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders, with whom you have agreed on many things in the past, for not speaking forcefully enough against the actions of Israel in the genocide in Gaza. By the same token, you’ve praised the recent victory of Zohran Mamdani, who has spoken honestly about the genocide in Gaza and who has become a source of hope on the show and among electorally-minded folks on the Left. What would you say is reasonable to expect from the politicians we support and when should that support be withdrawn or denied?

I would say the lowest possible bar to clear would be a clear and forthright condemnation of U.S. support for genocide. I know that both of them have made comments along those lines, but I would say that a real red line metric for me is ‘Are you going to call for a total blanket, cutting off of our client State', as it regards diplomatic support at the UN and shipments of arms in violation of International and U.S. law.

My harshest criticism of AOC, the one that people always reference, is her comment at the DNC about how Biden [and] Harris were working tirelessly for a ceasefire. I have high expectations of her because I supported her and it's along those lines that I think when the politicians who you support or who claim to represent you lie to your face about something as important as U.S. support for an ongoing genocide. I believe it's time to get out of the car or at least register your discontent with that particular stance. Going further than that, I would say that you can't expect too much of U.S. politicians—even ones you like for a variety of reasons, both good and bad. A bare minimum would be supporting some sort of Universal Health Care system, and if you can't at the very least support something like Medicare For All, which is the softest version of that, I don't really see what else you could be trusted on or how much there is to buy into.

While I have you, the Epstein story is currently dominating the news. Have you been surprised how much backlash President Trump is getting from commentators who would normally support him?

Yeah, it has been surprising to me because the one thing Trump has is a really direct relationship with the Republican Party voters. It’s his party. We’ve seen, time and time again, any Republican, any Right Wing news organization or media outlet or politician that attempts to buck him gets disciplined and reined in very quickly. Those that were once critical of him are now absolutely obsequious toadies to him because they know that's where voters are at. So, it has been a little surprising to me to see a schism develop over the Epstein Files. But it shouldn't be when you consider how brazen what he’s doing has been in this regard. I think to a lot of MAGA voters, whether it's QAnon, Comet Ping-Pong Pizza, and then Epstein, all of this is part of a master meta-narrative that almost has a spiritual component to which Donald Trump is cast as the Redeemer of America.

A big feature to a lot of what I think of as otherwise less political people who voted for him, was the promise that he would turn over the tables and crack open the door on all this nefarious shit that's going on out there, this huge thing that seems to be at the center of American politics that touches sitting presidents. Bill Clinton and Donald Trump have had dealings with this guy or personal relationships with this guy who ended up dead in federal custody. They understand the outlines of what something like this suggests. There's never any accountability. There's never any resolution. It just remains out there as this giant thing. I think given how all-in Trump went on stoking and playing to people's desire for there to be some kind of accountability, or the idea that he was going to lock up Hillary Clinton, he was going to send the Clinton crime family to jail. He was going to expose all of the elite criminals running our government and society. It shouldn't surprise anyone. It’s only been known for about thirty years. He’s thick as thieves with all these same people and the brazenness with which he's just saying now, “Oh, it's a hoax. Everybody look the other way. It's all made up.” After a good part of his political campaign was saying “Yeah, we're going to get to the bottom of this.”

Does it present an opportunity for Democrats, would you say?

It certainly presents an opportunity because this is the first time there's been a legitimate schism among his supporters. I think this would be Politics 101, trying to heighten and deepen those divisions or at least attack him on something where there is daylight between him and his supporters. It’s hard for them to continue to kiss his ass on TV over this issue. The opportunity’s there. I see some people running with it, but I just saw Nancy Pelosi on TV today, saying that the Epstein issue is a distraction from kitchen table issues. I don't know if it's a kitchen table issue or not, but you gotta love political instincts like that.

I wonder if you suspected that Chapo Trap House would have such lasting power when you started and I wonder what it's been like watching people come into their own, in part by listening to Chapo Trap House, and carry those values into the world.

To the first question, no. I never could have anticipated that I could make money doing it, let alone that it would last this long and I've always said I don't think the show would have been successful had we had any idea or ambition or plan to get where we are now. As Vince Lombardi said “Luck is the residue of skill,” but I still feel very lucky and one of the reasons I feel most gratified by the ability to continue doing the show, and our now ten years of doing it, is seeing all of the people that—I’m not saying wouldn't have existed without us—But I love seeing all the people that have taken a model that we started and showed could be successful and done their own thing with it and the DNA of our show and the lineage and the people who have been on the show going on to do great, great things in Independent Media, and podcast realm I find very gratifying. I think it would be probably the legacy of the show that I'm most proud of.

The post ‘I just wanted to do my version of an H.P. Lovecraft story’: a talk with Will Menaker of Chapo Trap House appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment