I first met Andrew Alexander and Alex Laird at Big Milk Expo, a comic fair (And precursor to Alex’s Frog Farm) that took place at the City Reliquary in Williamsburg on September 25, 2021. I had just moved to NYC from Pittsburgh, and was starting to acquaint myself with the local comics community— something I never took advantage of while living in the Steel City; home of french fries on salads and a rich cartooning scene. At Big Milk, I was immediately impressed by Andrew and Alex’s Riso comics, and it’s been incredible for me to witness the rapid growth of their presses (CRAM Books and Frog Farm, respectively) since then. All together, they’ve published about 30 titles by a diverse range of talent in the past 3 years, garnering critical attention and awards, all the while continuing to write and draw their own comics. Not only are they prolific, they show up: they are pillars of NYC’s indie comics community, and I consider myself lucky to rub elbows with them.

In April 2025, I sat down with Andrew and Alex to discuss how the sausage is made, gripe about living as a cartoonist in NYC, and preview what’s next for their small presses.

-Christina Lee

CHRISTINA LEE: Describe your press and how it came to be.

ANDREW ALEXANDER: I was running a comics collective called Weakly (with an A) with Max Huffman and Jack Reese, and then we were doing that while I was at the RisoLab, making books. And kind of right before COVID, we had been like, I don't know, like, not really focused on making comics and kind of going, everyone's going their separate ways. And I really wanted to continue to make books, and I didn't really want to be beholden to two other people who were slowing down. So I talked about it, and I was going to start in 2020, COVID hit, and then in the middle of grad school, I was just like, if I don't do it now, I won't ever do it. So I just got started.

ALEX LAIRD: Were you excited about working with buddies? I had a similar situation where I always wanted to have little “collab buddies”… Like we're gonna be the Odd Future of comics, or something like that.

AA: It was cool and fun, but I’m not very good at collaborating.

Is that what you learned from Weakly?

AA: I think I've always known it and I wish I was a better collaborator. I'm just like, you know, I'm messy. I'm stubborn. I know what I want. Sometimes you don't have the confidence to do things on your own; right away at least.

AL: I like the idea of collaboration, but I'm not, like, optimistic about it, and I know that sometimes I have to do a thing myself. But I think it has worked out for me more than you. I mean, I've made animations and even comics where, like, it's worked out only because of collaboration.

I was at the RisoLab before you technically… I had been making comics more seriously for maybe a year or two before that, before I moved to New York from Toronto. I was printing stuff off my laser printer in my first apartment in Bushwick. I found out about a Minicomics class at the RisoLab that was taught by Patrick Crotty… I’ve just been Riso printing there ever since.

When did you start making comics? Because you went to film school…

AL: I went to film school in Toronto, but I’ve been drawing and making comics since before high school. Film school bummed me out though because I wasn't good at collaborating with all types of people, even though I liked the idea of it, it was just people telling me something wouldn't work when they didn't know either. The fun in it for me was finding out. I found with comics I could get my ideas out better, and I could improve as an artist much faster.

AA: You were an Artist in Residence at the RisoLab, and you had an idea to do a book that was also going to incorporate a show, which in turn became Big Milk. And was Big Milk the first iteration of Frog Farm?

AL: Yeah. Big Milk was a live show series I did with Siah Files for about three years: It included comic readings, animation, and live comedy. We did about 20 shows, but due to a combination of having different visions and different time commitments, we stopped doing it. A few months after that concluded, I started up Frog Farm.

The big difference between Big Milk and Frog Farm was that Big Milk was just a live show with a few zine fairs too. With Frog Farm, I wanted it to be more involved, so I started publishing other people's work that I was excited about; whose work I thought needed more attention. I want to support people that I like, and that can come in a bunch of different ways. I thought it meant putting on shows, but also publishing physical comics is really important.

If Big Milk started off as live events, what compelled you to start publishing under Frog Farm?

AL: I always thought that publishing was harder than it was. I mean, it is hard, and it's draining and burns you out if you’re not careful, but I had all the skill sets that I needed for it from already putting my own stuff out.

I also thought I can't make my own work fast enough to keep up with the amount I wanted to print stuff. And I know most cartoonists hate printing their books. They hate assembling them. And I don't mind it. It's fun, busy work for me. So I realized I could probably do it…and I think this is probably the calculation that everybody who starts a comics small press makes… Or the other way of saying that, in a bit of a mean way, is that you're more of an adult than your other artist friends, and you're willing to put in that work to make something happen.

AA: Sure, I always think of it as like, there's one organized friend in the friend group. You can have a good party, and there's always one friend who has a shitty time so everyone else can have fun, right?

Why Riso?

AL: I think it's the same for both of us: It’s a cheap and easy way to make beautiful work. Also, all of my favorite cartoonists have used it with great impact.

AA: While I was in undergrad doing Weakly, SVA just got a Risograph printer like a year after we started, and so we were trying to sneak onto it. It was 2015, and you could print color on a Xerox machine, and it would be fine… It just wouldn't look good. People were also making two color Riso prints, and it was much more exciting for me because I had been doing silkscreen and lithography in community college. I got drawn in that way, but 10 years later, it's just because it’s cheap and I have a Risograph printer.

AL: Yeah, the trendiness wore off a while ago. Some people want to dismiss it wholesale because of how “cool” it is (or was?) but it's still cheap and relatively easy to make work with, so I’m sticking with it.

AA: I think the cheap part is a big factor, because, like, there's alternative ways to make things beautiful, but they're a bit more cost prohibitive… Or it’s print-on-demand, which has never been appealing for my DIY sensibilities.

Who are your guys' greatest influences? Who do you guys look to for inspiration?

AL: Michael DeForge, Patrick Kyle-

AA: You're a good ole’ Toronto boy. I mean, those were your artists; Scott Pilgrim too.

AL: Well more than– but yeah when I found that work, it lit a fire under my ass to make my own comics in a brand new way. Less so Scott Pilgrim, even though I do like it. It was cool seeing how all interconnected it was.

AA: I was a superhero kid, and I started reading comics again but more seriously in high school. My entry point was Top Cow. Then, I was suspended from high school… And when you're suspended from high school, you don't have anything to do. So, I made my mom take me to the library. And, you know, you read all of Watchmen, you read all of Sandman, you read all the library books. But then there was Kim Deitch’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams, and there were a few Fantagraphics books… And Blankets was out at that time.

In my senior year of high school, I had to do a project where you find an advisor and my project was “Comics”. So I was emailing people and going to meet Stan Sakai, who does, like Usagi Yojimbo. I emailed Kim Thompson a ton of times, and he gave me, like, Jaime Hernandez and Jim Woodring’s emails. I ended up working with this artist, Levon Jihanian, and he did backgrounds for Over the Garden Wall much later. He was up for an Ignatz the year I was working with him for a comic called Danger Country. He showed me how to color and I helped him flat pages and taught me a bunch of zine making things that you take for granted. He was in the same small town that I was from, Glendora. He showed me Picturebox stuff and Spark Plug books. He showed me Renee French comics and C.F. comics. So he kind of gave me the easy pass to you know, like all the good stuff.

AL: My version of that was just going to the Beguiling and asking the staff what I should read next.

What is the curatorial intent behind your small press?

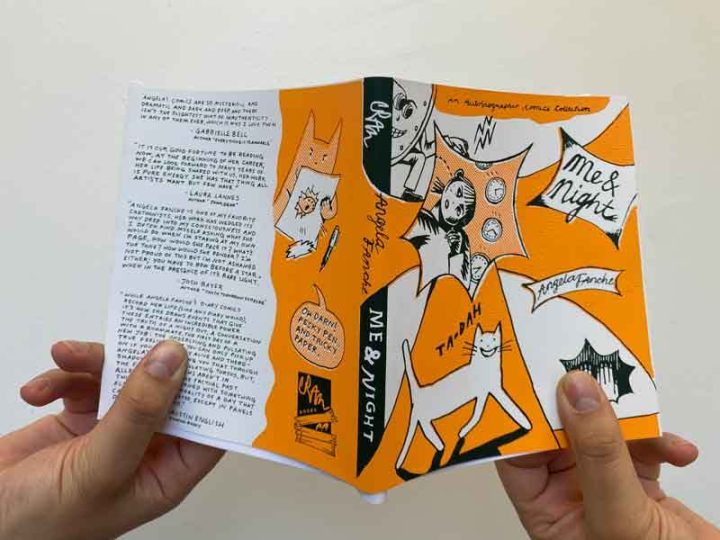

AA: The first book I published was Angela Fanche’s Me and Night. And that book started the genesis of the press, because I wanted to make a book that felt delicate and something that no one could make. I wanted to do justice to the work. That book ended up being 112 pages.

It wasn't until I made Cram #1 where I realized I didn't know why I was doing things the hardest way possible. The original idea was to create difficult books like really difficult books to produce.

AL: Well, you wanted to bridge the art book world with the comic world.

AA: I wanted to make beautiful comic books. Beautiful, yet accessible. My vision was weird comics but still focused on readable comics… Comics that are meant to be read. Not excluding avant garde comics or genre comics, but comics that can touch both and have some level of abstraction but still remains readable and accessible as its first and foremost thing.

AL: Yeah, I mean, comics get me really excited in a way that I can't describe. Frog Farm is basically just my taste. I want to see more interesting sci-fi, and I like cheeky humor. It needs to have something that excites me… I like it when all that stuff overlaps.

AA: Do you have a North Star? like someone else who did it that you're like, I want that. I knew the press I wanted to make was something like Picturebox, except I wasn’t so focused on making big editions. CRAM Books is closer to Oily or Spark Plug or Pigeon Press in that I’m making smaller books: comic books that are affordable.

Buenaventura Press is a really big influence to me. Harvey Kurtzman is one of my favorite cartoonists. I forget that he’s an editor; but editing is a huge part of his practice, right? I've always been influenced by editing and curation. It’s something really big to me.

AL: What gets me really excited is the interconnected worlds of artists, so I would definitely include Heavy Metal. The magazine had an interconnected world of sci-fi and other genre work, and it was cartoonists working together to publish something.

Fort Thunder is another big inspiration. I feel like it was a big artistic community that wasn't just comics: it was music and big crazy high concept art shows… A bunch of different mediums intermingling. I read Mat Brinkman for the first time, maybe like 3-4 years ago and it blew me away how intuitive and straightforward the cartooning was. Made perfect sense why so many people list him as a core influence.

Fort Thunder also makes me think about the timeline of a grand creative project like a collective or small press, and how those eventually burn out.

AA: 100%. It’s like 3-4 years, then it's nothing.

AL: And that was a bunch of people. But I'm curious if the burnout was because wrangling all those different people was too difficult or...

AA: I mean, Fort Thunder was a place too.

AL: Yeah, it was a place. And then everyone just moves out.

AA: Then there are people adjacent to it, like CF and Ben Jones…

AL: So it’s this big wide community; a world. That period in comics is very mythical in the way world building in a sci-fi or fantasy story would be, so I find that connection exciting.

AA: You did that video interview with Comics People, and it was about world building. I think Frog Farm is world building… even the live shows are a world building thing.

AL: There is world building in the literal sense of interconnected stories, but world building also goes hand-in-hand with community building. It’s thinking about how all these creators are related in taste and interest, but also about how they're different; how weird connections can be made through that.

Have you figured out how to connect the world building with publishing?

AL: I mean, this is kind of what the vision of the next stage of Frog Farm that I like to think I’ve been slowly working towards. I want it to all gel together in future projects, feel more interconnected without feeling forced. I created this new animatronic character for the live show in August called “Critter”, and I’m working on a little fanzine thing all about him going Hollywood and big timing everyone on the show. I also have plans for a deeper lore book all about Frog Farm’s ancient history…

AA: I feel like we both have a genre that is like our North Star. But like, you're very sci-fi, and I'm still very autobio, because I write autobio comics.

AL: Yeah, sci-fi, but I wouldn't call Frog Farm a sci-fi press though…

AA: I wouldn't call CRAM an autobio press…

AL: You do have a sci-fi book…

AA: The new Max Burlingame comic.

AL: Right. I’d consider Szarlotka by Jas Hice pretty close to autobio (although Jas has said it is not.)

What has CRAM Books and Frog Farm published this year?

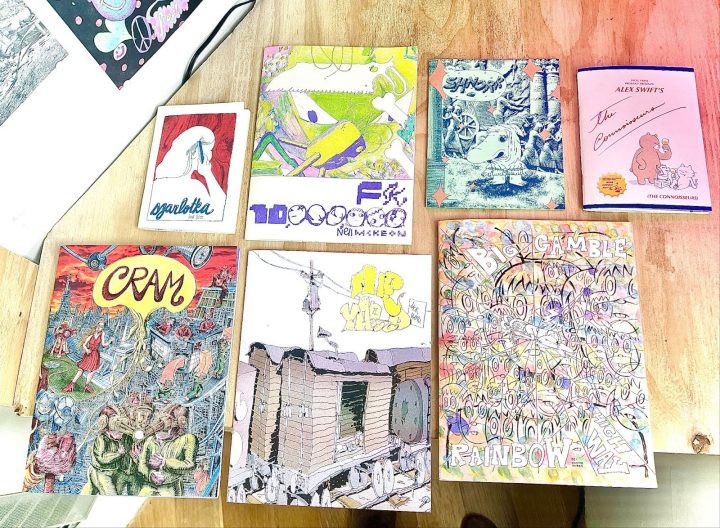

AA: I put out Big Gamble Rainbow Highway by Connie Myers, Traveling to DC by Stipan Tadić, Leon and Other Stories by Max Burlingame, and The Yard, the Jack Lloyd preview…

AL: I put out three so far? FK 10,000,000, by Nell McKeon, Shnork by me. And then, technically, it's not out yet, but The Connoisseurs by Alex Swift, who did Smoku Deluxe last May, it’s really really funny.

What is the most lucrative part of the business for you guys… Is it the tabling? Is it the distribution?

AA: For CRAM, it’s wholesale. There’s tons of really amazing shops around the United States. We each have, like, a list of 40 shops who order from us pretty regularly 2-4 times a year.

I go and shake hands with a bunch of comic shop owners and we talk shop, we talk comics. And that's a big chunk of sales for me. I don't sell that much online.

AL: I think I sell a bit better online.

AA: You definitely sell better online. We both do a good amount of wholesale. I probably do even more table sales. I did 16 shows 2 years ago.

AL: Last year, I did 10 or 12 shows.

Describe a typical work day.

AA: I wake up, I check my email, I come into the studio. I have to map out my day each time. Like, what do I have to do? Is it an admin day, or is it a print day? What books need to get made? Is someone coming in? I have volunteers for work-trade: Ashton Carless and George Olson, who run their own presses, Bootleg Books and No Good Books. They fold, staple, and cut books for me, and then in turn, they print their own work on the risograph and use the studio to make their own work.

AL: I am pretty similar to you; I go into my studio very often. I work most weekdays from 10AM to 5PM. Maybe I’ll stay at home and work one day and do laundry.

AA: Yeah, I go in six days a week.

AL: It ebbs and flows… It’s way busier at certain times, and then it’s dead, and I forget that it gets dead. Then I ask myself, “Oh, okay what do I do?” Luckily, I was good about that this winter, and I made a new comic.

AA: You’re better at making comics than me while doing all this stuff.

AL: I hadn’t made a comic since I started Frog Farm.

AA: You just did.

AL: Before this winter when I drew Shnork, I hadn't finished anything.

What would you guys say are the biggest challenges with running a small press?

AA: Money, yeah… Money. Next question!

AL: [Laughter] Yeah, pretty much. But also for me, it’s deciding what to concentrate on, so maybe it's not that for you?

AA: Yeah, I feel like I know what I want to do in publishing, but I'm trying to figure out what form it will take. Do I go bigger? Do I go smaller? I’ve now decided to offset print books soon, and we're both running Kickstarters to get to the next step.

AL: That's the direction that we're both going in. But it's also a model that we've seen cartoonist friends and other small presses do.

AA: Lucky Pocket Press, sure.

AL: Perfectly Acceptable and Peow2 way before them too…

I was listening to a podcast about Nancy Myers, the movie writer, and how all of her stories are about women who are trying to have it all. And I kind of feel like I'm trying to have it all. And what I've learned is that I got to choose a few things at a time.

AA: She's the GOAT.

Do you feel like you're trying to have it all by making comics and also publishing other people’s work?

AA: I feel I do the thing where I compare myself, and I'm like, what if I went through with this other timeline? Where I made a graphic novel that I focused on for 3 years. So yes, I do do that thing, but in so many different ways. You know, I think you're more successful at having it all.

AL: I think I realized that, like, you can stop doing something for a while and then do another thing and then go back to the other thing.

AA: No, that doesn't sound right (laughs). I asked Denis Kitchen this because he’s also a cartoonist. He's a really good cartoonist. He kind of sacrificed his career to run Kitchen Sink, and I asked him about how he makes his comics and runs a press, maybe, like, two years ago at CXC at a bar, and he was like, “Yeah, man, you can't do it. There's no secret way to do it.” I was like, “Sick, all right.” If Denis Kitchen can't find the time, then that's fine because Kitchen Sink is so important. His comics are so good; you're gonna just be happy to try your best.

What are the advantages of being a cartoonist running a small press versus doing it as a fan or a curator?

AL: I feel when we were both starting to make comics, it seemed like publishers were publishers, and they weren't cartoonists, and I'm sure some of them were, but it kind of had this feeling that, like they were pretty separate, and that you don't cross that line. And I found it interesting when we both started publishing, that we both still wanted to make comics.

AA: Is it a bad thing? I don't know. Do you think it's good?

AL: I think it's good. I think it gives me a perspective and makes me empathetic towards the cartoonist. And a lot of the cartoonists that are making the work that I wish I could do as a cartoonist, which gets me excited. So, yeah, what do you think?

AA: I think it's made me a better publisher. I think it's made the art direction, creative direction, whatever you want to call it an easier, better, stronger process, because it's like I have an image for it, and I can either make the image, or I have an idea of someone else who can do it better. Or if someone has an idea, I have better vision in my mind of what it could be. And as someone who makes art, there's a lot of trust in the process, and I put a lot of trust in my artists, because I know that even if it's not right the first time, it can be fixed and it could be changed, and it's like an ongoing process. I think a lot of people who aren't making art, you know, they either get hung up on their own ideas, or they get really scared of the process of art making, the uncertainty of it. We're both working in publishing and as artists, and both are working with uncertainty and we've kind of, you know, mastered the ability to sit in that uncertainty.

AL: I think there are more people like you, me, Nick (Reptile House) doing it this way who are artists and publishers. It comes from a lot more people learning to self-publish extremely competently in the last few years. Feels like an obvious evolution of that.

I think that’s also why there's more artists who are self-publishing or publishing like us is because there are less business-minded people who are choosing to publish because it's a bad business decision right now. Like, I think it maybe seemed like it was a better idea, let's say in like, 2014 when, like, “Adventure Time” was booming. Like, oh, maybe I can get a TV show deal out of finding the next hot IP in comics. So there was a business decision on that, and now, like, that's all gone. And so it's just the artist’s love of the game.

AA: Ball is life.

How would you describe each other’s work, and how it connects to your publishing practice?

AA: Yeah. I've only seen your work as its Riso form and I think a lot of the ways you use Riso is really smart and really simple and really effective in a way that a lot of people don't do and I see how your use of Riso has influenced how all your artists is working with it for one. But then also the stories that you want to tell: they’re worldbuilding, they’re sci-fi, and I think it's not necessarily in the avant garde space, but in, like a playful outsider-y way. Not necessarily referencing pop culture, but in that mode of referencing…

AL: I like when people are being cheeky about the way we consume media; it's something I'm really interested in. Exploring how a project can be consumed, like having a fake magazine article, or like a video game guide, and using that as a mode to do a comic within that, is cool. Like having the realization that a Nintendo Power article from 1998 that’s mostly just screenshots of the work in progress gameplay of Ocarina of Time, it almost reads more like an abstract comic than an actual games journalism piece.

AA: If I called your work related to some kind of nostalgia, is that offensive?

AL: I don't think so. I think nostalgia is like a dirty word nowadays, but I think it's also interesting to explore if you do it in a responsible way. I think there's an irresponsible way to do it, and I think seeing all this AI stuff and how people are just like making nostalgia content with it shows how unoriginal a lot of that stuff is. But I think that stuff is slop and it feels like slop, and I think there are still interesting uses of nostalgia that don’t go into that territory.

AA: Nostalgia as modes. Like exploring the limits of a medium of a past form as a way to develop something new.

AL: Yeah, you said it well. For you, I think you respect people who are kind of brutally honest about what their life is like in their comics. I feel like I could definitely see that similarity with your comics and the first CRAM comic you did with Angela. Obviously there’s differences, but they're like, some major similarities. What gets you excited about making comics I see in what you're publishing, and it's less so even from reading your work, but you literally telling me, like, what type of work excites you and then seeing that kind of reflect in the work you put out.

AA: I value honesty. When I had to do my Eagle Scout board, they had– there's like fucking 13 values where, like, a scout is loyal, honest, whatever, whatever. And they're always like, what's the one that you value the most? And I said, honestly, and they were like, “More than loyalty?” But honesty simplifies everything. It makes joy easier. It makes sadness easier… It clarifies stuff. It makes things move easier.

AL: I mean, that's why I like your autobio comics, and also the stuff that you publish. I think I heard you or Angela talk about how sometimes it can get disgusting, how honest people are in their comics, but there is kind of a deep satisfaction to that too.

AA: There's good honesty and there's bad honesty. There is, obviously, like a line where there is your own personal life but to relieve yourself of, like tiny lies and like little hold ups, it's kind of a beautiful thing. And I don't know, I think comics, it's an intimate medium, and so it's in my mind, that honesty should happen in comics, right? Like in a film, there's a lot of artifice in production itself. And in prose or writing, there's a lot of disconnect between how you describe something, how much language something deserves and time. But in comics, it's like you articulate bodies and places and objects, like, everything is articulated in drawing. And there's a lot of room for expression and openness for simple stories and really, really elaborate stories, fiction or nonfiction. And both of them excite me. But I guess, yeah, at the core, there needs to be that thing that I look for in my own work, which is an honesty.

AL: I feel the satisfying thing about good fiction is what's good about autobio, but you can get there really quickly and easily with autobio.

AA: You get to get to the emotion in stories. In fiction it's a lot of like, what's the story? Why is it important? But in “auto-bio”, it's like, yeah, this happened, and the realness of it makes it important immediately. But good fiction does that too. Good fiction has that immediacy and that honesty, that truth-saying, where you insert yourself in it.

AL: It can be lazy and gross, but when it works, it feels good, yeah

AA: When it works, it feels perfect.

You guys stated earlier that funding is the biggest challenge when running a small press: Have you found a solution?

AA: Usually, I'll sell a book, and the money from selling the book goes into the production of the next book. I'll front the cost with a credit card or cash, or however it's paid for. We’re looking into Kickstarter to allow me to have less risk.

Right now, as a Riso publisher, 500 books cost me $1000+, which mostly goes into paper, ink, and masters. Now that I’m transitioning into offset printing, the goal with a Kickstarter is to front the offset printing production costs.

AL: The big, big unsaid cost with Riso is your labor, so the Kickstarter is to front the cost of offset printing the books, it’s literally also offsetting labor costs and risk. We both talk about how our backs are hurting from assembling so many books: we’re not spry 21 year olds anymore. It takes a lot of work to continuously assemble books. We're both going to continue doing it, but it now makes sense to start doing larger print runs, where it's more about putting work into distributing than assembling.

AA: I'm running a Kickstarter because I'm trying to change the direction that Cram has been going in. I need money to offset print books. Right now, I have a Risograph printer and all the resources I need to make risograph books, but I want to make higher-production comics.

AL: I think printing a central project like what you have with the Cram anthology is what I think can help grow Frog Farm as a whole. We don't have a Risograph printer like you do, so that’s something I would like to fundraise for as well.

Those are my goals for Frog Farm’s Kickstarter. Making Frog Farm sustainable and to make it go to the next step. We both, I would say, as far as small presses go, feel accomplished, but there’s also a plateau we’re both on and ensuring potential growth is what gets us over that.

AA: Nowadays there's Fantagraphics and D&Q, and then small presses at our size… But where are all the medium presses that I looked up to? Like, where's Spaceface Books, where is like, Sparkplug, Pigeon Press, Picturebox…

AL: Yeah there are no more, or at least not too many, medium-sized presses anymore. I think when Koyama closed during the pandemic, it felt like a major tone shift.

A big problem in indie comics is that there are not a lot of platforms where you can gain confidence in your work and get people to engage with your work. And that was the most frustrating thing for me, which is why I started the comic readings. It gave me a platform to read my comics in front of people. I would make comics for the shows I would put on, and it was awesome. And then I was also able to do that for other people that I liked, and that was great, too. Artists want places for their stuff to be seen. If you're making work, you need it to be read, and you need it to be acknowledged so you don't feel like you're going insane.

I think the nicest compliments I've gotten about the Frog Farm live shows is another cartoonist who has made a genuinely incredible comic, being like, I wouldn't have made this unless I was going to be on the show. That's great. Forming a new avenue for cartoonists to be able to make work for.

Why do you think comic readings are so important?

AL: It’s good to get people in the room.

AA: It's good to show work early. Comic readings are another great deadline that's not a comic show.

AL: Right, it’s an excuse to finish a comic and then be able to try it out. You know? And I think that's like my biggest point of pride for putting those together, like people made a new thing which is the best I could ask for. Worse case, they’re reading an old thing that is also probably great.

AA: People have been getting better at comic readings too.

AL: Zine Not Dead was what got me wanting to organize a better comic reading show. I had never been to a Zine Not Dead show before - I had never been to Chicago until last year, but just from social media and from the few videos on YouTube I found, I could tell they were new and interesting. They were doing it a bit differently - more refined. Seemed like they had it figured out. They had fun characters. Brad (Bred Press) kept doing a devil character where he dressed up in a red cape and he called it Red Man. Sarah Squirm did a weird performance on it, before she got on SNL. I think Zine Not Dead was even on an episode of that Netflix TV show, “Love”? One of the characters who’s married but is poly takes a hot date to a show. Anyway…it seemed like they had figured out a new formula to organize a comic reading I hadn’t seen before and I really wanted to do my version of that.

AA: I mean, Panels to the People (in Brooklyn) was always a good show, too. It was much smaller. I think we did the same one, didn't we? I did another comic reading that was at… what's that video game space on 14th Street, between 7th and 8th? (Editor’s note: Baby Castles)

Anyways, I did a reading there. I had maybe four of my friends come, an ex-girlfriend and her brother, and then there were maybe, like, four other people. So it was like, really small. It was, like, four or five o'clock, and I read sad autobio; like really, really depressing autobio to a room that went like, “Oh, what?” Then eight people went on, and then my ex’s brother said, “I'm really glad I came.” and I was like, “No, you're not shut the fuck up.”

AL: I think New York is special for having events because of its size. I think other people in other cities do these events, and they're at a much smaller scale. I think what's special about New York is that there's so many people, and they're all interested in some type of weird thing.

AA: So you can get a lot of weird people into a room. It's not hard to fill a room in New York…

AL: Which is nice. I feel very positive about New York because I have access to the printing at the RisoLab, and that I can get people in a decently sized room together.

AA: Yeah, I agree. I also think… I'm gonna fluff you a little bit. I feel like you've inspired smaller communities, other cities in America, to do comics readings. Like, yeah, there's one in Columbus. There's one in Portland. Meatmolls (Molly Lecko Herro) is organizing one.

AL: Yeah, and Secret Room has one.

AA: There's readings happening in LA, Mikey Heller. Comics O Clock. Also Permanent Damage.

It seems like one of the biggest reasons why you guys keep on self-publishing is because of the community…

AL: I think it's really, really important. I think community building is ground zero of having people engage with your work. Community needs to be there, then it turns to people starting to talk about the work and then writing about this work, like with Bubbles Fanzine, which I think is a really important part of it. Community is getting people into the same room who like the same stuff. It’s a big deal for a lot of people, and for me.

AA: I moved to New York and was on the outside of the scene looking in. There was a different Vanguard when I came to the city; older cartoonists who felt like I couldn’t interact with them for whatever reason.

There are a lot of young cartoonists that I know now, and I guess the general relationship is similar to the ones that I had with the old vanguard, except they're more confident. They were pushing through anyway. I started working at the RisoLab, and there I kind of like, rethought the idea of community, because I got to spend so much time and work with so many artists.

AL: It’s just good to be around people because then you become a presence. You get recognized. And just being around is important, even if you don’t talk.

I think it’s a universal need for a lot of people. I don’t think hanging out online all the time is cutting it. Even beyond comics, in another small community like indie animation there are similar events being organized - Hellavision and Malt Adult share a lot of the same ideas of community that I see with these comic readings.

AA: Yeah. I mean, for me, communities are really important. That’s what makes life fun, right? Because friends are people who are interested in the same things that you are. I love comics, but most of the time I'm just alone in my studio, and I forget that I have a community.

AL: I think community also means having beef with people and disagreeing, and that’s healthy.

AA: That's not even beef, that’s just discourse. And I think that’s what brings it all together.

How would you describe the indie comics community in New York?

AA: The indie comics community in New York is made up of small friend groups. Every community is just a bunch of friend groups, and there's this friend group and that friend group, and then we do a comic show, and everyone comes together, and then we all share ideas, and we kind of break apart.

I talk to maybe, like, six, or seven cartoonists on the regular. There's a good amount that I work with, but it's not like I'm texting them memes every day or something… but I'll come over here and I'll talk to you guys, because our studios are nearby. Community is huge because in New York City; there's hundreds of artists; there's painters, and there's other communities that intersect.

AL: People have different definitions of what they think comics are, which is totally interesting and maybe a bit frustrating. It’s not really as true for other mediums.

AA: Yeah, there's a genre divide…

AL: There is a genre divide, and then like, what you're saying of artists working in other modes or mediums that goes to informing their comics. There’s fine art comics, fandom for anime…

AA: Original manga that's not fandom related at all…

AL: Yeah, which are two different things that aren’t connected at all. And then there's people who have one foot in indie animation as well as comics. All of these people we just mentioned don’t have anything to do with each other, and some don’t even know the others exist.

Comics are my favorite thing, but I also really like animation. I show animations at Frog Farm shows because they're in the same vein of the comics that I would like to see more of, and that informs the comics I make, and the comics inform the animations I make.

How can we make the industry more sustainable?

AA: It’s really hard because of the audience. I'm friends with a lot of people who buy books from me. You meet people going to so many shows, and some of them are maybe die-hard comic fans. There's probably like 10,000 US comic fans. Maybe there are more and I'm wrong… Maybe it’s more like 50,000 to 100,000.

AL: I'm of the mindset that we can grow it. It felt bigger before we got into it. I think there is a way of growing the audience. There seems to be a reignited excitement for printed stuff again, right?

AA: There definitely is. We’re in New York, and in New York, there's a much bigger art book scene than there is a comic scene. The two scenes have small overlap. It is small, but there is overlap. Riso also unites the two. I mean, the RisoLab unites those scenes, right?

AL: It's a really, really good resource, not just for cartoonists.

AA: The RisoLab is good. But there’s an art book scene that doesn't fuck with comics.

AL: No, they put their nose up because no matter how artsy and weird the comic work is. I really get the sense sometimes they think it's juvenile.

AA: The only way readership grows is something like Blankets to organically, in a pure comics way, to grow it. Someone has to make a graphic novel that blows up.

I think part of why we're making comics at this smaller scale is because nobody has time to make a graphic novel like Blankets. The economy is just not as good. It's really hard to sit at your parent’s house for two years and make a graphic novel… Well, and your parents can't afford to have you sit at your parents’s house!

AL: I think it's more basic. The animation boom’s over, the graphic novel boom is over. I think the truth of the matter is it’s because the pandemic happened and then the election, so the economy's not good right now.

AA: Rich people got really rich, and the middle class sort of disappeared.

AL: I will say this, what you said about how you know all the people you sell comics to…

AA: I don't, but I know a good chunk of them.

AL: People come to the Frog Farm comic reading shows and I don't know who a lot of them are. And that's like, probably my coolest, humble brag. So that's why I feel more optimistic. There are people who are interested in this stuff that I don’t know directly. I’ve tried to figure it out also and it’s not clear. Where are they coming from?

AA: I'll also say this is a huge distinction between us. Like, for me, I'm making comics. I make the books. Sometimes I spill into art books, but people who like comics, they come find me.

You’re running the show that is trying to answer that question of who's buying comics and how to get more people to it organically. It’s a big question I have all the time because you're throwing a show, and it’s bringing people in New York coming to a show who may never know comics, and honestly, might not even know the comedians there either. I don't even know how they get to the show. And then they're like, “Oh, I just stumbled in, and I love this, and I'm buying the comic now.”

AL: I mean, that's the best compliment. And that's what makes me feel optimistic about it: to grow beyond this mythical, 10,000 people core audience. I think there is room for growth. And I think some people are really Doomer about it. They think that's all we have, but I don't think so.

AA: I am being a bit Doomer about it. I truly think even if comics doesn’t grow, it's not a bad thing. There are always people looking for alternatives. There are always people looking for more, and comics will always have endlessly more…

AL: Yeah that’s right. It's the most cutting edge: new aesthetics and new ideas for telling stories constantly. It’s like an incubator that blows up past its natural state every 10-20 years.

What do you hope for the future for the indie comics community?

AA: There’s a part of me that hopes we move away from a graphic novel-centric mindset…

AL: I think we already have in the last five years…

AA: Floppies are so much better than a graphic novel you spent two years on making no money. It's brutal: you wait for an advance, and then you don't sell enough copies.

AL: I think we both agree on our platonic ideal of what a comic is: like, a 30 page floppy - that's the right amount of story. You can tell a really concise, but robust and smart story at that length. And some people don't work in that form; some people work shorter. But I feel like that's the nice juicy spot for me. I think of someone like Grayson (Bear) who has cranked out a few of these very well crafted 30 pagers.

AA: That length is also a chapter in a good graphic novel…

AL: …And you can think about it like that. I think some people would argue for something even smaller, like a 5-page thing or something like that. I think 30 pages is the ideal.

AA: Floppies are the future, but there's not a lot of places where you can sell floppies. But I’m always looking. I'm always thinking about asking the newspaper guys to sell comics at the newspaper stands. Part of me wonders, is it worth it for them? Is it worth it for me?

Is the future of comics more brick and mortar comic stores?

AA: I don't know because I like a physical comic. I have this belief that the internet isn't as permanent as people think it is. People are like, “Oh, there’s this kind of archival element to Instagram,” but all of it could all go away in seconds. It's not good record keeping. It's a terrible archive.

AL: That's why I like comics, why I like books. Like, on top of everything else, we've said, it feels good to have a pile of artwork.

AA: I love this 70 year old comic that I just bought. It exists and it's good. I can still read it. It has all the elements, like ads… It's record keeping, and that's exciting for me. Ties into the autobio shit that I'm obsessed with. Like, I don't know, I like print. Print is great. We haven't really said that, but we both love print.

AL: Love an object.

Frog Farm has Ignatz Award nominations for “Outstanding Minicomic” for the titles, Connoisseurs by Alex Swift and Szarlotka by Jas Hice. They will be debuting Valley Valley/Idella Dell by Audra Stang at SPX this year.

Cram Books has Ignatz Award nominations for“Outstanding Collection” for Them Shaped Clouds by Max Huffman and “Outstanding Comic” and “Promising New Talent” for Big Gamble Rainbow Highway by Connie Meyers. They will be debuting Momix presents Dadix by Sam Szabo this year.

The post ‘It can be lazy and gross, but when it works, it feels good’: NYC Small Press with Alexander Laird and Andrew Alexander appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment