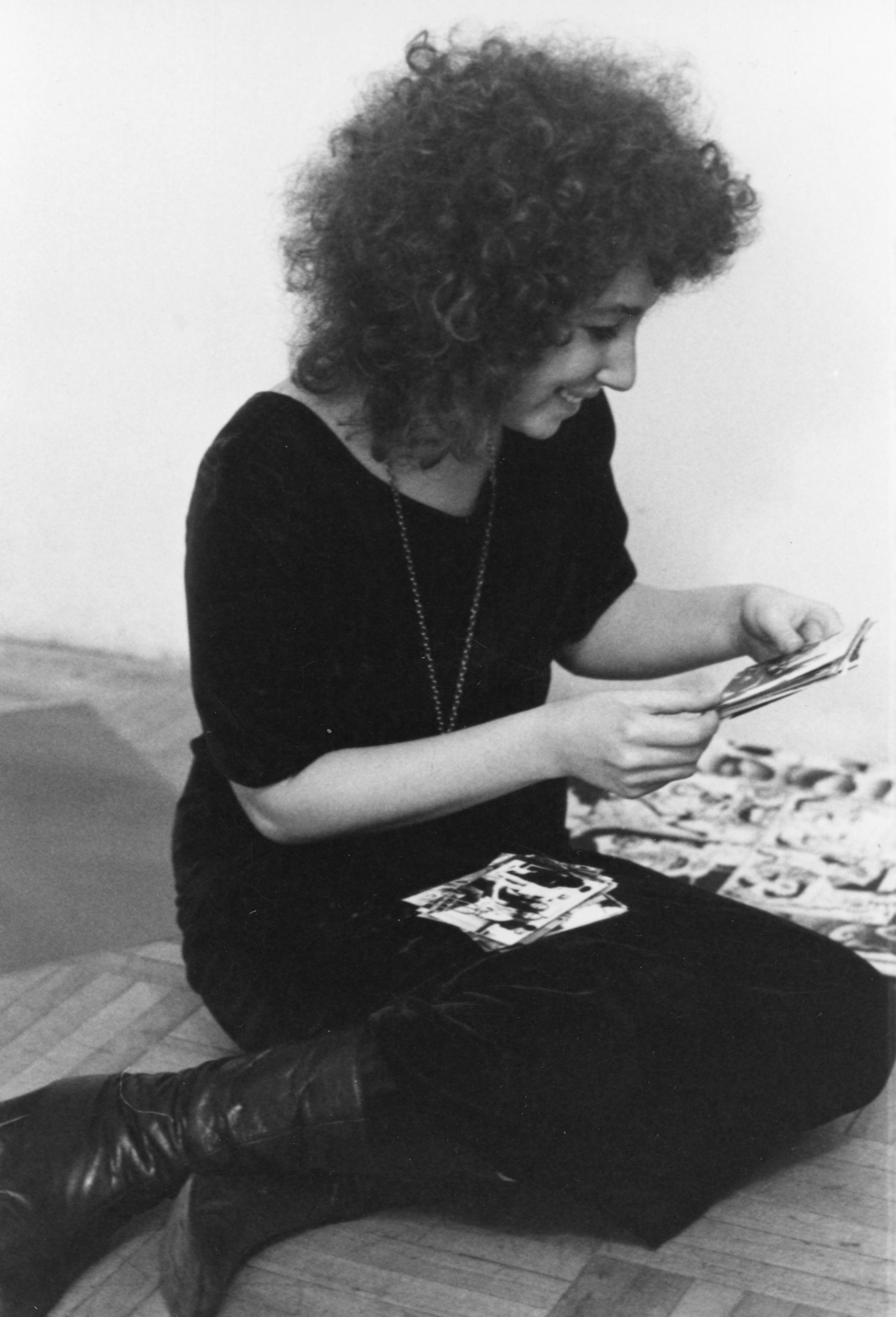

Nancy Burton, née Nancy Kalish, aka Panzica, aka Hurricane Nancy, died Sunday, July 20, 2025. She was 84. Predeceased by her husband Victor Burton, Nancy is survived by her two sons, and many grandchildren.

One of the early American underground cartoonists, Nancy was known by many names and lived what sometimes seemed like many lives.

Born in New York City and raised in Far Rockaway, Queens, Nancy was interested in art from a young age. Like many of her generation, she grew up visiting the city’s museums, and while her parents let her read comic books, her fascination with newspaper comics began at her friend’s apartment. “I used to go to my friend Angela’s house. In my house we only read the New York Times, which didn’t have comics,” Burton said.

After high school she attended Buffalo State Teachers College, where she became enamored of the Western New York Art Movement. Unlike many other cartoonists of her generation who rejected — and often hated — abstract expressionism, Nancy was inspired by how many of the artists, in particular Clyfford Still, used space, in ways that would influence her work for the rest of her life.

“The guy was a master of color, space, and size. He had his own universe. There are people who don’t like abstract expressionists, but to go into a room filled with that was walking into a different universe. I was very influenced that somebody could do that and get away with it,” she said of Still. “If you look at my work, it has nothing to do with his, but it was influenced by it. The freedom to do something like that. The freedom to say, 'I can do that. I can make the biggest painting with the craziest colors and weirdest shapes' and it’s wonderful.”

After traveling through Europe with her first husband, they moved to New York City where she discovered the East Village Other when it launched in 1965 and began contributing to the paper. The EVO, as it was known, was once described by The New York Times as "so countercultural that it made The Village Voice look like a church circular” and was one of the cradles of underground comics.

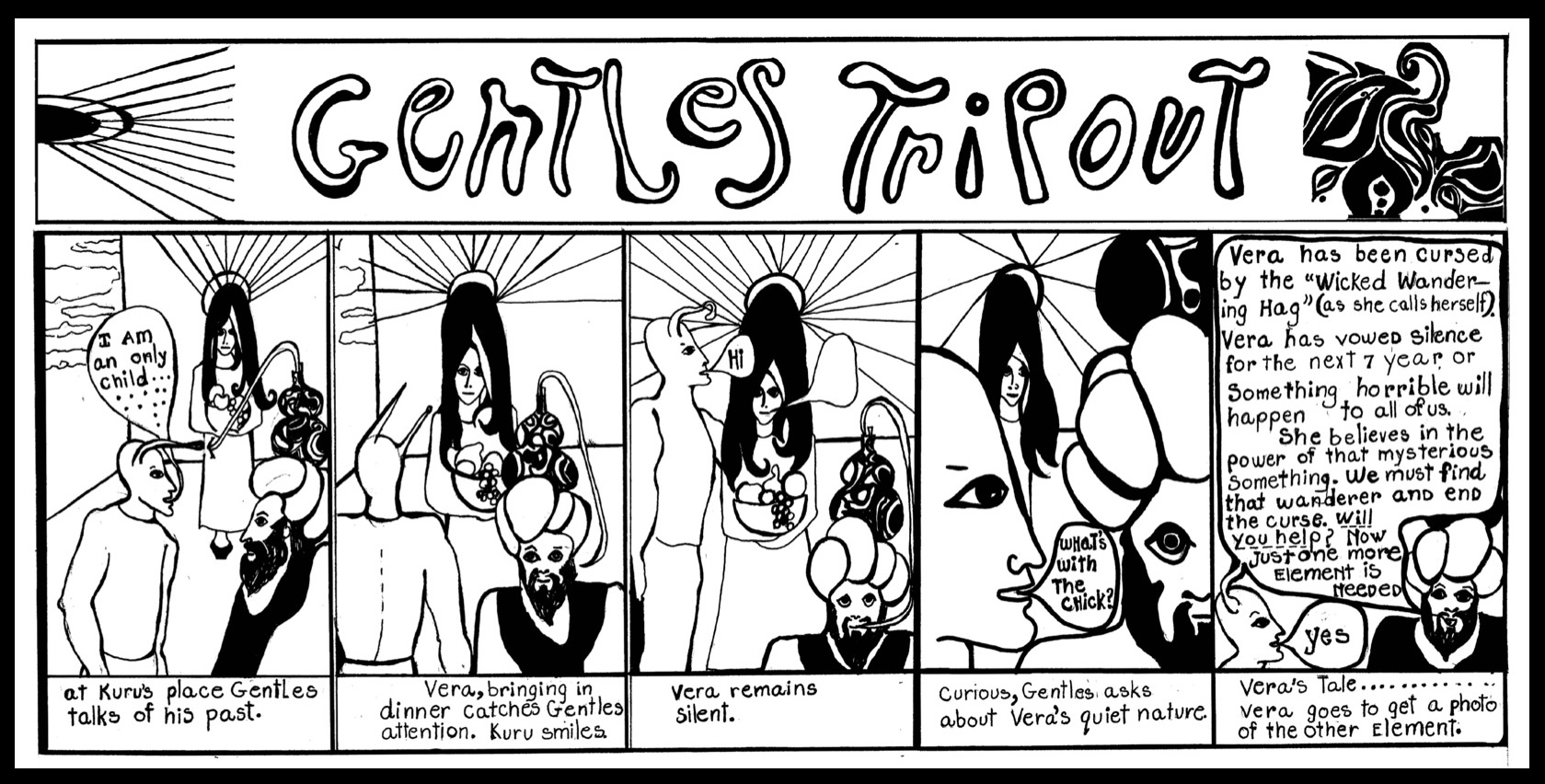

Her comic strip Gentle’s Tripout, was one of the paper’s early comics standouts. Patrick Rosenkranz and Trina Robbins both admired the strip and compared the style she utilized to Aubrey Beardsley. In her books about the history of comics Robbins named Burton as the first female underground cartoonist for the work, which was not obvious at the time because she signed the strip “Panzica,” her married surname.

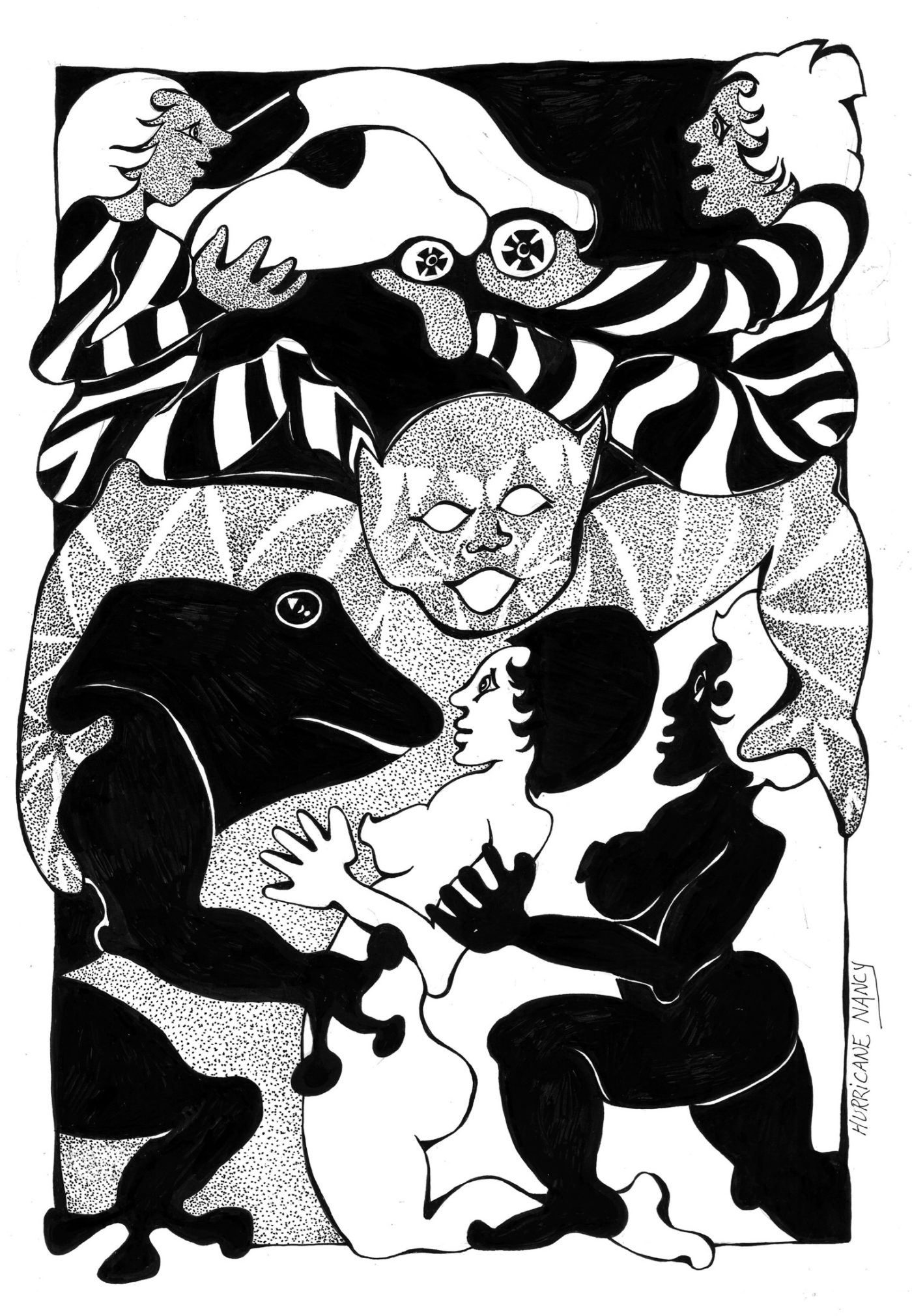

Nancy used “Panzica” for a time before using her maiden name “Nancy Kalish” and then finally settling on the moniker “Hurricane Nancy.”

“There was a prize fighter called 'Hurricane' Jackson training in Far Rockaway. It stuck. I thought the name hurricane for a fighter was cool. It was an allusion to strength and power. You know how certain things stick and impress you as a kid? I didn’t come from a family that watched fights or were into that. They were more intellectual. I was just so impressed by the spirit of that name,” she said.

During this period Nancy contributed to many publications, including multiple zines made by her second husband, the late John Dowd, including Peter Rabbit’s Birthday.

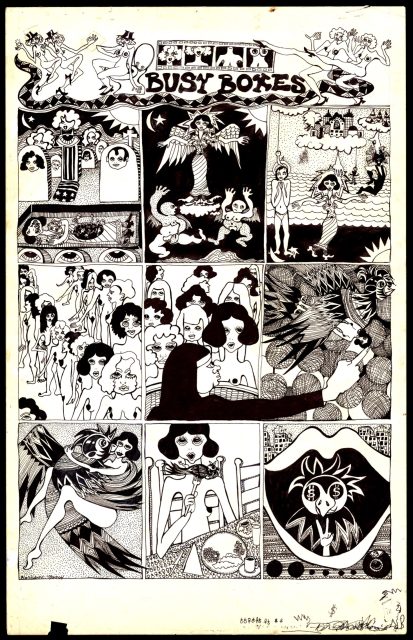

In 1969 Burton contributed to Gothic Blimp Works, the East Village Other’s spinoff publication. Her full page comic strip Busy Boxes ran in four of the series’ eight issues and show the influence of old Sunday comics pages and the psychedelic poster movement that was underway and which she had seen during her time in California. It also represented a rare attempt by her at crafting a longer narrative.

Her last comic credit in this period was 1970’s It Ain’t Me, Babe, the all-women’s comic edited by Trina Robbins, who sought Nancy out to contribute to the project.

During this period Burton’s life had a Zelig-like quality, as she told stories about the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock, Timothy Leary and the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix and Melanie, and many others. Nancy was part of a generation that, as many people have described it, went a little crazy as they rewrote the rules of so many aspects of society and culture that we now take for granted. But there was a cost to all of that.

Her life was volatile, something that she attributes in large part to her drug use. “I was irresponsible. And become more and more irresponsible with drugs. Other than that, I had a very good time. But the irresponsibility then created things that one does to others that are pretty unforgivable,” Burton said. “I wasn’t Saint Nancy.”

Over the course of my many conversations with Nancy, she could be incredibly sharp, but more than once I asked a question and it took her a few seconds to realize that she had no idea. “I’m sorry,” she told me more than once, “that was many trips to rehab ago.” There were things she didn’t want to talk about, of course, but she could be honest about why she didn’t remember many things.

Over the course of my many conversations with Nancy, she could be incredibly sharp, but more than once I asked a question and it took her a few seconds to realize that she had no idea. “I’m sorry,” she told me more than once, “that was many trips to rehab ago.” There were things she didn’t want to talk about, of course, but she could be honest about why she didn’t remember many things.

Her first marriage to the poet Krystian Panzica ended in divorce, though technically they were not divorced for many years afterwards, as Panzica did not file the paperwork. Her second marriage was to the artist John Dowd, with whom Nancy had two sons.

For years Nancy was quiet about what happened and why she disappeared from comics. I never explicitly said that we would need to talk about it, but I think she understood that she needed to open up about why she left comics and the end of her second marriage. It was a story that, as she was speaking, was clear she had rehearsed, but she became emotional as she recounted leaving her family.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever committed acts for which there was no justification and no forgiveness. As well as fear of doing irrational actions in future intimate contacts,” Nancy said. “I could only see doing art in association with my doing destructive things."

In the 1970s, Nancy went to rehab. Afterwards she became a counselor and for decades was a respected member of her church and community. She fielded calls from people to the very end of her life.

She married Victor Burton in 1994 and the two lived together in Clearwater, Florida, until his death in 2021.

In 2009, Nancy was diagnosed with breast cancer and during chemotherapy treatment, she began drawing again. “It was like a wakeup call. Why do I want to live? Why do I want to overcome this?” Nancy said.

“A woman who was also doing chemo told me about how she gardened each day. I thought, how boring and white middle class. Wake up! What the fuck are you doing? What reason do you actually have to live? I needed a goal and my personal goal was always to be an artist. I dropped a major part of my personal inner life and this is what I really wanted to do. Then the pictures started to appear. My sense of weird humor returned. My attention un-fixated from my body and I began drawing kartoons. I was completely relieved and didn’t care what anyone thought about the work. I just started doing it and dreaming again.”

Her husband Victor set up a website, and she posted cartoons there and on YouTube for years.

When she returned to making art, Nancy worked steadily in a serious way, making one picture at a time, and when she finished, starting a new one the next day. It was a disciplined way of working, taking advantage of the time and clarity that she hadn’t previously had, but one can see traces of that approach in her early work. When she dropped off a Gentle’s Tripout strip to the East Village Other and was told that they weren’t interested in the strip anymore, she put the half finished strip she had started aside, and went to work on something else.

I first met Nancy when I assembled the Oral History of Wimmen’s Comics, which was published in the The Comics Journal in two parts in 2016 to accompany the release of the collection from Fantagraphics. Nancy didn’t speak much about why she left comics but credited Trina Robbins, who reached out to her about It Ain’t Me Babe and who Nancy said always seemed to keep track of her. I conducted a solo interview with her for the Journal the following year and a few years later we began to put together the book Hurricane Nancy, which Fantagraphics published in 2024.

When I spoke with her after the oral history was published I told her that so many of the Wimmen’s Comics cartoonists asked me some variation of “You talked to Hurricane Nancy? What was she like?” She was puzzled by this and I’m sorry that the book didn’t come out earlier so that she might have had the chance to meet more cartoonists.

Nancy may have stopped making art, stopped thinking of herself as an artist and tried to forget her life, but she kept a lot of her artwork. Most of the work in the Hurricane Nancy book are pages that she kept and brought with her when she moved. In 2021 she donated all her artwork from the 1960s and '70s, along with a selection of her more recent work, to the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University, where she also left her remaining artwork in her will.

“I was over the moon to be connected with one of the pioneers of women’s underground comix — it is such an honor to us to be chosen as the home for preserving this important work,” curator Caitlin McGurk said at the time. “Anyone interested in exploring the feminist history of comics will find this collection to be a treasure. It is imperative that we continue to document and preserve the history of women working in this and all eras of cartooning, and this collection is an invaluable part of those efforts.”

The donation happened prior to the book’s publication, but I think that it meant more to her than the book. Nancy called me after an online meeting with a group of women from the museum and she was emotional recounting how this group talked about her and her work.

At this time Nancy began sending art to Henry Chamberlain, the cartoonist and TCJ contributor who runs the website Comics Grinder. Chamberlain published Nancy’s comics, both the single images she drew along with comic strips she experimented with, and occasionally Henry colored some of them in ways that showed both an interesting approach to color and an understanding of what Nancy was doing.

In our conversations Nancy would talk about the work of Chelo Amezcua, and Mark Rothko with a mixture of academic learning and awe. We spoke about poetry, Grace Slick, Laurie Stone’s substack newsletter. I can’t say when she ceased to be the person I was writing about and became my friend, but I have no doubt that she understood it before I did.

Nancy and I talked occasionally, and as her health declined, we spoke on the phone for what turned out to be the last time. She gave me the contact information for her executor, and asked me to pass along messages to people. She asked after my mother, who was being treated for breast cancer, just as Nancy had been. She said that she had left all her art to the Billy Ireland, and that Caitlin would know what to do with it.

Her faith was something that we didn’t talk about, but in our last conversation I asked what it was that she believed. She said that she had done work and had learned about what she done in her past lives. That she and I had known each other before. That we would know each other again.

The thing about a Hurricane Nancy cartoon is to give yourself to the logic of how a story operates. There is a way that knowing Nancy could be like that. She could be very open, but also kept her life very compartmentalized. Being an artist was important to her. It was who she was, and who she wanted to be. For a long time she associated it with her destructive behavior, and even though she counseled artists over the years, I’m not sure that she ever quite let go of that association.

At the bottom of her Comics Journal interview there are comments from people who say that they’ve known her for decades and had no idea she had made art and had these experiences. When the book was published, she said more than once that it had made people fans of my work, but not hers. Many people around her were uncomfortable with the art, or just weren’t sure what to make of her artwork. She sometimes smiled when she said that, but I knew that some of those comments had hurt.

We shared a sense of humor, but while I struggle to accept compliments, Nancy knew how rare it is to be understood and appreciated and she took those moments to heart. From working with Gary Groth, and the book’s positive reviews, to working with Henry and his enthusiasm for her work, from her interactions with Caitlin and the others at the Billy Ireland, to Bill Kartolopoulos’ generous and enthusiastic introduction at the New York Comics and Picture-story Symposium after the book’s publication. I’ve sought to be aware and keep such gratitude and appreciation in mind in my life.

She said that we would do this again, and I could hear the joy in her voice at such possibilities. In a Hurricane Nancy comic, you follow the uninhibited line where it leads. It is entirely sincere, and even when it leads to an unexpected place, it feels inevitable, even if it’s not the choice you would have made.

“I look forward to it,” I said, before we said our goodbyes.

Henry Chamberlain

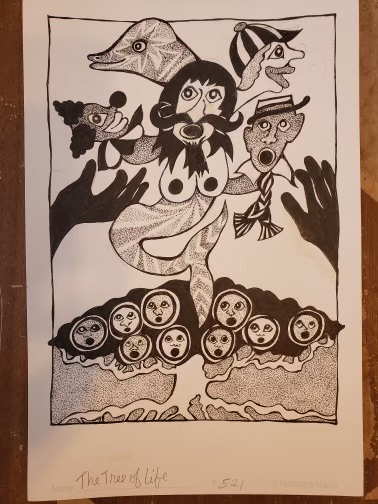

I got to know Nancy through our correspondence and it became clear to me this was a special and unusual connection. She contacted me about submitting her artwork to be posted on my blog, Comics Grinder. I immediately said yes. And that led to back and forth emails with observations and goodwill. I got to study her work closely and was struck by how uninhibited it is: the lines run smoothly and seem to go on forever. Her characters, whether human or anthropomorphic, are so uncanny: lustful, soulful, and joyful. I have a deep respect for Nancy as an artist and someone who kept to her core belief, to be true to herself.

Bill Kartolopoulos

I first heard of Nancy Burton in It Ain’t Me, Babe, the first underground comic — and first comic book, really — written and drawn entirely by women. A photo of the issue’s contributors shows several of them together in a group shot. Two other artists, not present at the scene, sent in their own individual photos. One of them was credited simply as “Meredith;” that was Meredith Kurtzman, daughter of Harvey. The other was Nancy Burton, credited here only as “Hurricane Nancy.” With an unruly mane and a knowing smirk above her folded arms, she was a mysterious figure with a name like a tall tale from the Wild West. I was intrigued, of course. Who was this person? What is the legend of Hurricane Nancy?

Later, while researching comics in the East Village Other, I found a very early underground comic strip that I had never seen before called Gentle’s Tripout by someone who signed their work “Panzica.” Gentle's Tripout was not the first comic strip in the EVO — that was Captain High by Bill Beckman. Captain High humorously alluded to the stoner lifestyle in the manner of a university comic strip. Gentle’s Tripout was different. The stunning first installment showed what underground comix could be: psychedelicized, illuminated manuscripts stamped out on cheap newsprint. The strip manifested a countercultural ethos in aesthetic terms, including organic, curvilinear forms and polyptych structures that linked individual panels into overall compositions. Although Gentle’s Tripout only ran for several installments in 1966, I wondered why this interesting and obviously historically important comic wasn’t more well known and remarked upon. And who in the world was Panzica?

Eventually I learned that Hurricane Nancy and Panzica were both Nancy Burton, a founding mother of underground comix who has gone by many names. Her body of work in the field was not large but was foundational, visionary, and personal. Throughout her work her inky lines explore the protean boundaries between the self, the other, and the cosmos. I am grateful that recent archival editions of feminist underground comix and Alex Dueben’s own dedicated recovery work have brought Nancy Burton’s full contribution back to light so that no one will ever wonder who Hurricane Nancy — and Panzica — were ever again.

The post Nancy Burton, aka ‘Hurricane Nancy’, 1941-2025 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment