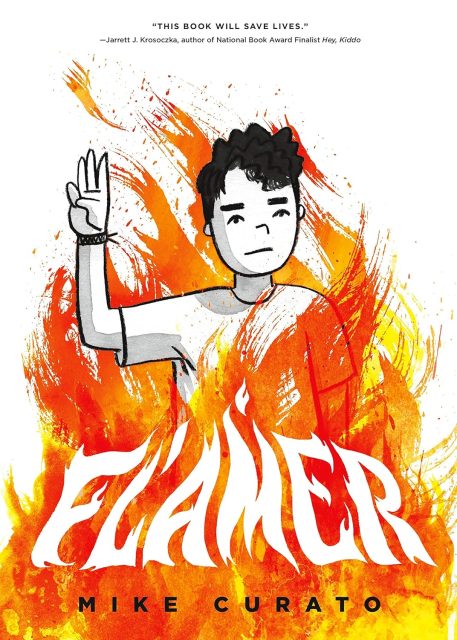

Flamer was Mike Curato’s first graphic novel, but by the time it was released in 2020 he’d written and drawn multiple picture books and Flamer was clearly the work of someone conversant in the language of comics and visual art. The book was a moving story of life as a closeted gay teen, winning near unanimous praise and multiple awards including the Lambda Award for Young Adult Literature. Later it would become one of the most challenged and banned books in the United States. By hateful people who did not read the deeply empathetic book, and did not want a moving, anti-suicide book to be on the shelves.

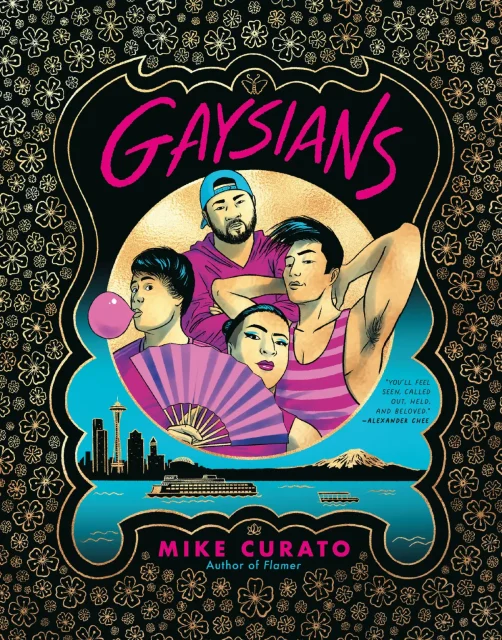

His new book Gaysians is a leap forward for Curato as a writer and artist. Balancing a large cast, the book is bigger, longer, and more complex in every way. Some of this the result of crafting a book for adults versus teenagers, but it was also a much more involved process for Curato as he detailed in our conversation. In some ways there is nothing new for those who know Curato's work. In his picture books and Flamer one can see an artist who is adept at many styles and approaches, and running through all his work is a deep empathy and understanding of all his characters. That said, Gaysians is a moving and important book where his talents come together in a way that was a joy to read and one of the best books of the year. I had the pleasure of talking with Curato recently about the book. Twice actually, as the recorder broke the first time. But he was kind enough to do it a second time.

-Alex Deuben

ALEX DEUBEN: Mike, I liked Flamer but Gaysians really felt like this leap ahead for you as a writer and as an artist. Does this feel like something different? Were you conscious of setting out to make something different and to push yourself as an artist?

MIKE CURATO: First, thank you. Because Gaysians is an adult book, I didn't feel as limited when I was writing it. I could really talk about anything that I was thinking about or feeling. That's not to say that Flamer isn't entirely based in truth, but Gaysians felt like I did not have to filter myself. It was very liberating. And I really pushed myself with the writing.

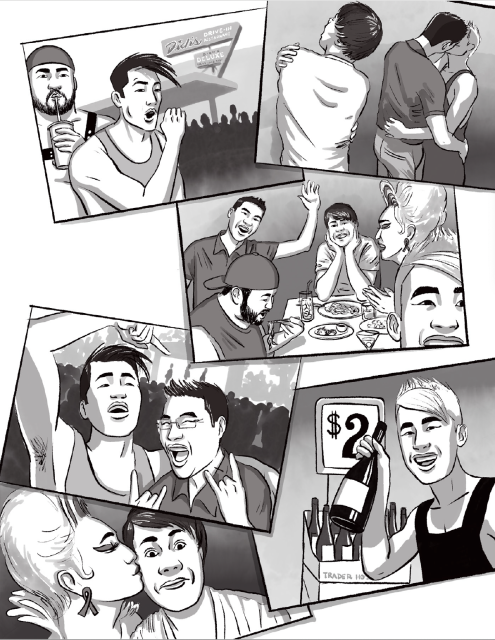

It's also a much longer book. It's a much more complicated plot. We've got four main characters instead of one. It was also interesting to play with these four main characters, make sure that their plot lines are all equally important and balanced, and weave them together. So yeah, it was so challenging as both an author and an artist. It took me a very long time to write. In the original draft, there were six main characters. The first draft was so long. My agent was like, this is going to be a thousand page graphic novel when all is said and done. She recommended I cut the main characters to three. I was like, no. I had to advocate for John. I was like, let me write a new draft, and you tell me. Then she said, I'm glad you kept him. So the writing went through several iterations before and after I sold the manuscript. And then the illustration work was just a beast. I've never worked so hard on a book before. I mean, I was pulling double, triple shifts towards the end there. It was ugly. It has to get ugly in order for it to be beautiful sometimes. And yeah, it was just a real labor of love. It's obviously way more detailed and more realistically rendered than Flamer was by design. I really wanted these characters to look realistic. I really wanted them to look like real Asian people. Because we're not always portrayed realistically in comics.

You utilized a much simpler style for Flamer.

It was very much by design. It's a book for teens, about teens. I wanted something that was kind of blurring the lines between a cartoonish style and a raw sensibility that I think represents that age well. That crossover between childhood and adulthood, I feel like it's an angry cartoon. That's what I was going for.

It definitely does that. Flamer was about one of those hinge moments in adolescence of things changing. Or maybe becoming aware of things changing? But you captured that very well.

Thanks.

It was also a book very much rooted in pain in a lot of ways. It's very much an anti-suicide book. And Gaysians is a book that's very rooted in joy.

That was the goal. I'm not the first person to say this, but obviously a lot of queer stories of old are always rooted in fear and sadness and despair. That's not to say that those things aren't present in this book. But I think you're right in that there is a celebratory element that runs through the book in spite of those things. It's the joy that these friends give to each other and experience together that gets them through all of those hard times.

It's a book about joy and it's a book about community.

Yes, community and chosen family.

It's the kind of book that doesn't feel the need to explain. We've seen more of this in recent years, and it’s an open question whether we'll see it more in the next few. There's that famous Toni Morrison quotation about the very serious function of racism is distraction. Forcing you to explain and justify. This felt like a book where you don't explain what it means to be gay, what drag is. You're not explaining Asian culture. You're not pandering to an audience. You're just telling a story and people can catch up.

People can catch up. There's moments of explaining for AJ, who is the newbie, right? But that's a little more specific to people like AJ, who are newly out queer Asian people. As I was once. But this is a book that I made for queer Asian people. Everyone else is welcome to read it. And encouraged to read it! If people have questions, there is a plethora of resources online and in your libraries. Maybe I shouldn't say plethora. There are resources that people can use to educate themselves. I wanted someone like me to be able to read this book and feel at home. Not feel like there's always someone else in the room that's like, let's pause so that Johnny can catch up.

As one writer told me once, Wikipedia exists. I don't need to replicate it in the book.

Right. Use Wikipedia. Make a donation. [laughs]

As you said, AJ is a character who's new to Seattle, who's just come out recently. You did what people have done for forever– and will continue to–you introduce a new person to a setting or a group, which allows you to explore and explain it.

Yeah. It's an old trusted device. Which lets you explain, but not over explain.

I’ll say it so you don’t have to: You weren't pandering to a white or straight or cis audience.

Yes. It’s hard to escape that gaze. G-A-Z-E. There's plenty of gays in this book. But hopefully, hopefully the white gaze is not among them. I mean, there are white characters in the book and the characters talk about their experience.

You said the writing kind of took a while. Talk a little about that process and how you work.

I started playing around with the idea in 2020 during COVID times. Since, you know, we all needed something to do. It was a little off and on at first. Come 2021, I was really working on it a lot. It was 2022 is when we sold the book. I was working on it a lot, but also illustrating other books at the same time. So there was a lot of stop and go, but it was just a huge undertaking. I'd never done something like this before. Flamer feels like a short story compared to this. The page count is not much longer than Flamer. But it's a larger trim size and very condensed. Whereas Flamer, you get like maybe three panels of page, this one, you got like eight panels on a page and a lot more dialogue. A lot more dialogue. A lot more detail.

It's much denser.

In my hallway I had a thousand post-it notes. That was me trying to arrange all these moving parts. Trying to organize my thoughts visually. I had sensitivity readers work on this. I interviewed about thirty different people during that process who shared their experiences. Their ethnic experience. Their queer experience. Including gay people, queer people, trans people. I needed different perspectives. Because part of the point of the book is that Asians are not a monolith. And I'm definitely writing outside of my experience for many of these characters. That was a process as well, like making sure I do my homework and get it right.

This was a book about community. And you kind of wanted to be respectful of that community and what it meant, what it was.

Yes, it's for the community. I want them to feel like this is for them. And it's not just my own fantasies of who people are. Which is something that we experience so much, right? People don't do their homework. And we see these sort of two-dimensional queer Asian people over and over. When we do make it into a mainstream story? I always wonder about those characters, what are they really like? What else is going on with them?

During the writing process, I'm sure even if you're not drawing, you're thinking sort of in terms of the image. But are you kind of writing a detailed full script with dialogue?

I write in script format. There are a lot of art notes as I write for my own reference, but also for the editor to be able to understand what's going on visually, in case it's not clear from just the dialogue. There are a lot of wordless scenes in the book as well. That's all articulated in the manuscript. It's important for me to document that as I'm writing, so I remember when I start illustrating, oh, right, that was the idea. My process with graphic novels, I’ve found to be different than working on a children's book. Children's books, I usually draw and write and draw and write. I go back and forth and the story forms that way. But with graphic novels, I really focus on the writing first. Then when it's done, I start illustrating. And while I'm illustrating, then I'm also editing again. Because sometimes I can show and not tell, right? So I can pare down the dialogue a little. Or something will happen in the illustration that makes me rethink the scene and rewrite parts of it. So it's very involved.

As you're scripting, are you breaking it down page by page? Or are you just breaking it down by scene with art notes?

I've seen how some people are able to wrap their head around writing per page. I am not one of those people. I definitely write by scene and I figure out the visual pacing after I write the script. That's part of the drawing stage. I mean, bless those people who are able to do that kind of mental gymnastics. I'm more low to the ground. I need the thumbnail stage. I figure out my pacing in the thumbnail stage. And then the comping, which is tighter than my thumbnails, but not really a finished sketch. It's more legible to the average person. My thumbnails are probably more like hieroglyphics that only I have the key to understanding. The comps are what my editor finally sees visually. In the comp phase I am also setting up my InDesign file and starting to place my type. Because another thing that evades me is being able to figure out how much space to leave for the speech bubbles. It's really hard. And it frustrates me because I was a graphic designer for a very long time. I feel like I should have a sense. But I'm always surprised in really frustrating ways. I actually ended up adding thirty pages to Flamer so that all the type could fit. But it's interesting how that works, because I couldn't envision it being shorter than it is now. I think making room for the type does help visually in so many ways.

The art needs a certain pacing separate from the dialogue. And sometimes you just need another panel here. And you need a beat here. And there's a way in which it's not a straightforward process.

Personally, I need a scene to end at the bottom corner of a page. It's a pet peeve of mine. I can't stand it when a scene ends mid-page. I'm like, no, please don't do this to me. Just finish the page. In Gaysians and Flamer, I always finish the scene on a right-hand page also. In the new one I'm working on, I did not have that luxury. I don't have that kind of real estate. But it's always going to end at the bottom right of the page. A trick that I learned in making picture books for so long is the power of that page turn. The anticipation that's waiting at the bottom corner that makes you want to turn that page. I need that. It's exciting to have that at your fingertips, literally. Whether it's the end of the scene, it's like, oh, and then what? Or if you're in the middle of the scene, and you're like, oh, my god, what happens? So thank you, picture books.

You mentioned that you interviewed people. Where in the stage that was. Did you have this general idea of AJ moving to Seattle and meeting a bunch of people and just having the characters?

I started writing with my own experiences. I was just mind dumping for a long time. The beginning of the story was AJ moving to Seattle, much as I did in 2003 when I graduated college. AJ and I have different backgrounds, but very parallel experiences. I'm also the model for AJ. I gave myself the 2003 Bieber haircut. So I started there. I was interviewing people throughout the writing process. And as I would speak to someone new, I would get new ideas, or I would revise and edit things that I've already written. People shared really rich and important experiences that I wanted to include. And I had to think about how to get those stories in the book. Is it a part of a main character story? Is it a supporting character story?

The book is dedicated to three Asian friends of mine who I met in Seattle. The story is very inspired by them and in honor of them, but they only exist in the characters in trace amounts. I'd say each character is an amalgamation of many different people. They just became their own characters. It's not like I look at one of the characters and immediately think of one specific person. They become their own people. They're like my new friends. I feel like I've really gotten to know them.

How did you decide on the color scheme for the book? Because you mostly used two colors and it was very deliberate.

I try to be really intentional with color. I originally had a grand plan of a two-color printing process. A pink and a blue. Then when I started playing around with final illustrations, we figured out that it really wasn't possible what I wanted to do with two colors. So it's actually a mostly faux two-color process. But it's all four color. I chose the blue as a more foundational color. I felt like it represented Seattle well. You know, we have some gray days in Seattle and I didn't I didn't want gray. I wanted a little life in it. Something about the vibe of Seattle is very blue to me for most of the year. The pink adds some excitement and queerness to the color palette. I also use black and white for flashback scenes, memories, dreams. Not all dreams. There's a dream in color.

The blue is for the most part the foundational color, and the pink I used to highlight different things. It's a fun color to play around with for some emotional highlights. Pink and blue is a sort of bisexual color palette. Sometimes when you combine them, you get these purples that are really nice. Then the Pride scene. I just feel like you need a rainbow in a Pride scene. There's not really a way to convey that with two colors. I tried and it just didn't look right. So I went full rainbow for pride. Then towards the end, there's a very celebratory scene at the Lunar New Year party where I introduced gold. Because you just can't really do like Lunar New Year without gold. I had pink instead of red, but it is the Lunar New Queer Party. So it fits.

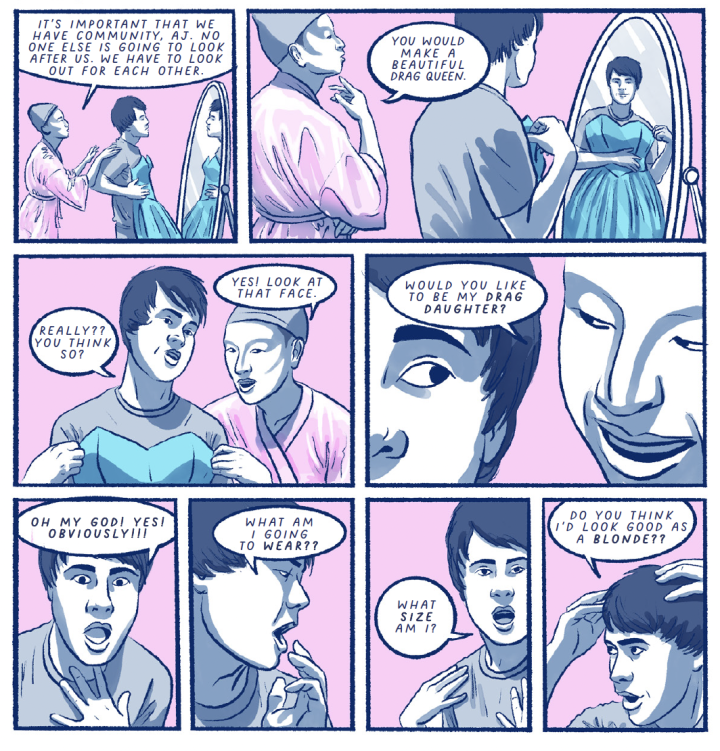

It definitely fits. But talk a little about drag. Was this kind of part of the book and a part of AJ's journey and experience from the beginning?

I always knew that drag would be a part of the book. It had such an impact on me personally. And also, not just the queer community, but the queer Asian community has such a rich drag tradition that I felt was important to include. AJ is really able to use drag to find himself in a lot of ways. K is this experienced mother for AJ, who teaches him the tricks of the trade and guides him. There are these scenes where they’re getting ready, practicing makeup, and drag becomes a sort of metaphor of AJ trying different things. Pulling himself out of himself, and trying to wear himself on the outside. He’s kept it all in for so long. He's very repressed in so many ways. Drag really gives him this confidence towards the end of the book that he wasn't really owning before.

That scene where K is saying, do you want to do drag, I would be your mother. I think that’s one of the most emotional scenes in the book. I thought of it as this moment of becoming. When K suggests it and AJ is immediately like, what am I going to wear? How am I going to, do this?

It's in there. He just needs a little push.

Yeah, exactly.

And when they first start talking about drag earlier in the book, he's a little hesitant. Oh, I don't know if I could do that. There's some fear, there's some shame. But that's also how he feels about his life in general, right? He doesn’t know what he’s doing. He knows he wants something else for his life than what he’s been doing. But everything's very scary. There's a lot of trial and error for poor AJ. And he falls a lot. But he has K and his other new friends to pick him up and get him on his way.

In the same way, Flamer captured a lot of that feeling of adolescence, Gaysians very much captures being twenty-something.

Gaysians is definitely new adult, whereas Flamer is more young adult. AJ is very much based on me. And Aiden from Flamer is obviously based on me. Part of how I got to thinking about Gaysians was going, what happens to someone like Aiden when he gets older? That made me think about my own twenty something experience. and what I learned from that. Again, I didn't have something like this book in my early twenties to kind of look to. I think it would have been helpful. I think it would have put me at ease a little bit. It was a hard, hard time. I think I had some expectation of, okay, I'm finally coming out, and now everything's gonna be easier. It was more like I was trading in some hardships for new hardships that I didn't foresee or understand in the moment. I was like, I'm just going to come out and make gay friends and every gay will like me, because we've all been through this. It's gonna be wonderful!

Coming out, moving to a new city, it’s like, everything’s going to change, it'll be great. And it's like, well, there’s a few more steps.

Right? Especially because I hadn't fully found myself. I had found enough footing and enough voice to get me out there and move in the right direction. But there were still parts of myself that I needed to find.

The post ‘It has to get ugly in order for it to be beautiful sometimes’: Mike Curato on his latest, <i>Gaysians</i> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment