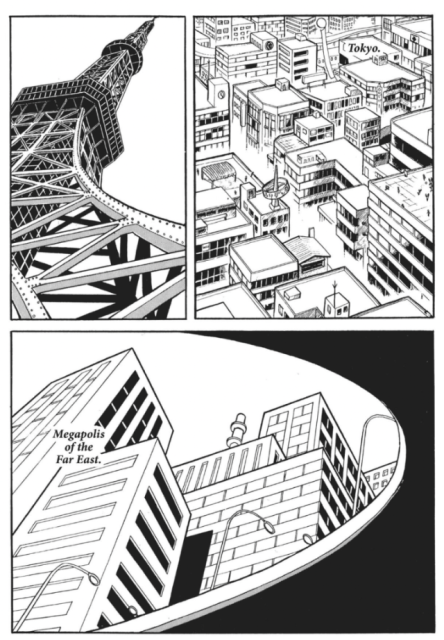

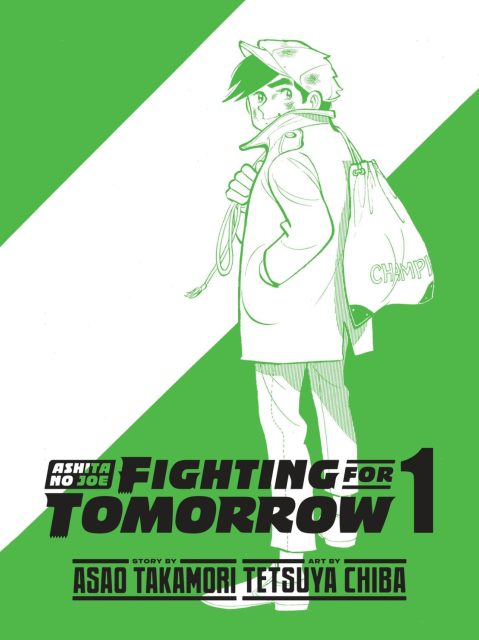

The city towers above us. Below us sit the slums. That is how Ashita no Joe (“Tomorrow's Joe,” gracefully localized for English in the new Kodansha translation as “Ashita no Joe: Fighting For Tomorrow”) begins. An areal view of the dense Tokyo cityscape, at once starkly smooth and gritty, peers up to the height of Tokyo tower, office buildings stretching serenely over the shadow of an underpass. Drifting down, we see derelict homes, following the wind pushing dust and trash along its ragged course. Against the wind, amid an unpaved road, a young man appears, small, unwashed, his baggy clothes looming over his strong, slouching frame. There is a spark in his eyes. He presses forward.

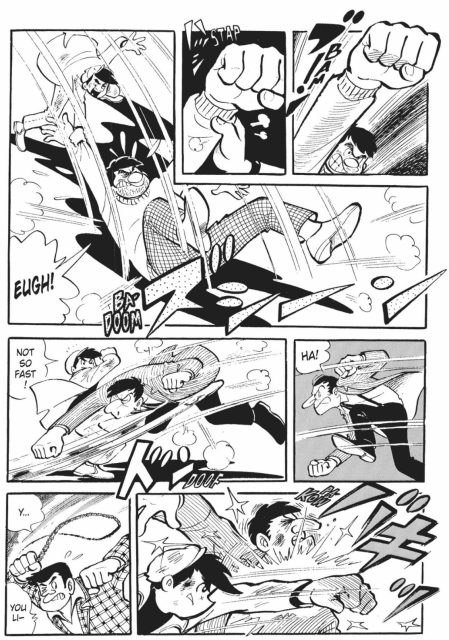

Already in this prologue, artist Tetsuya Chiba has delivered the thesis of the story written by Asao Takamori (the penname of the prolific sports manga author also known as Ikki Kajiwara) — Ashita no Joe is the story of an everyday man pressing against the current of urban oppression, the everyday folks crushed under the boot of commercial opulence. Seeing Chiba's thick and expressive linework has the same excitement as discovering an artist like Alex Toth or Steve Ditko and recognizing for the first time the connective stylistic tissue of many comics which followed. The impassioned, visceral cartooning of Go Nagai's Devilman cannot exist without the impact of Ashita no Joe, nor could the rollicking maturity of late period Osamu Tezuka. These are influential comics whose touch expands across the medium's history.

Alongside Sanpei Shirato's Legend of Kamui, Ashita no Joe is among the manga embraced by the political counterculture of Japan's New Left and student movements over the late 1960s and early 70s. As if summoned by the growing disparity of America's late capitalist slide into fascism, these graphic icons of communist resistence are both arriving in English translation as of this year, albeit in thick compilations at a price point which may make the proletariat shudder. It is tempting to call the commercial shonen series Ashita no Joe the mainstream counterpart to Kamui's Garo counterculture, but as Joe McCullouch rightly pointed out in his recent review of Kamui for the Journal, Kamui was itself too a popular work by an artist, joined by assistants, who had long found success capturing the imaginations of youth in prior works. Ashita no Joe indeed is not so much an alternative to Kamui but an artistic and intellectual bridge, taking the socialist contemplation of the period drama to the immediacy of the present day, all in the pages of a Boy's magazine.

Kamui embeds its hero within a microcosm of society, not even introducing the titular ninja for many chapters of complex political intrigue and class struggle that define his existence. However, Shirato goes even further out and weaves class struggle into the struggles of the natural order, presenting thickets of woodland where wolves struggle amongst eachother for command of fragile resources. There is no forest in Ashita no Joe to speak of, just dirt paths and shanty towns, a tensely interwoven “outskirts” within city life. There are no animals vying for territory here, but the games and schemes of improvrished children, vying for survival in a mini-society within the subjugation they are too young to yet totally grasp. A Greek chorus of mischevious minors is hardly a novelty in shonen manga of any era, but make no mistake, the younguns matter. Children are both free from oppression by dint of ignorance and by that same lack of understanding a most vulnerable class of the oppressed. Joe Yabuki is the gang leader of children.

Joe Yabuki is a thief and a scammer, blowing in with the wind and sinking to the dirt in street fights and fraud. Danpei, an old master boxer living in a shack by a bridge, the mockery and fascination of children, sees a spark of old glory in Joe, shining through the grit of his desperation. Joe has nothing, underhanded as he is he fights for survival. That fight swiftly lands him in juvinile detention, but even in this desperate situation Danpei continues to train him. Joe learns to love the form of boxing, and gradually his desparate fight becomes an art and a sport, but no less desperate, a literal inspiration to his fellow inmates.

Joe Yabuki is a thief and a scammer, blowing in with the wind and sinking to the dirt in street fights and fraud. Danpei, an old master boxer living in a shack by a bridge, the mockery and fascination of children, sees a spark of old glory in Joe, shining through the grit of his desperation. Joe has nothing, underhanded as he is he fights for survival. That fight swiftly lands him in juvinile detention, but even in this desperate situation Danpei continues to train him. Joe learns to love the form of boxing, and gradually his desparate fight becomes an art and a sport, but no less desperate, a literal inspiration to his fellow inmates.

Like Kamui's expansive debt to Shirato's past ninja stories for the rental manga market, Joe's tomorrow is carved out of a lineage of sports manga made for the same. The recent translation of Fukui Eiichi's early 50s martial arts serial Igaguri: Young Judo Master from Ryan Holmberg and Bubbles makes an informative point of reference. The foundational sports manga's artistic form weighs heavily into Joe's tomorrow - the cinematic pacing, the masculine rivalry, the discipline of practice balanced by the spontinaeity of play - and like Joe's boxing, Igaguri's Judo forms the backdrop of a discourse on the spirit of the nation. However, Judo is a traditional sport and Igaguri is a manga of traditional ethics, bound to honor and nationalism. Igaguri is an upright young man, stout and firmly bound to the moral code of the Japanese art of Judo. Joe is gaunt, angry, firy and desperate, battling not only his opponents but his inner fury and ignorance as he wrestles with the crushing weight of poverty. It's a vision of sports not unlike that Kinji Fukasaku's vision of the yakuza underworld in his Battles Without Honor And Humanity film cycle -- a world of proletariat for whom the patriotic vision of living by a code of conduct has already been denied. The traditions and virtues of sport are not gone, if anything their importance has become even more consequential, genuinely intertwined with Joe's lessons on form -- Joe does not simply learn defensive technique, he must learn to humble himself against his ambition and antagonism. But virtue is approached from the outside, a drunk and miserable coach training a juvenile delinquent in a way of life denied to them by place, circumstance, and tragedy, while the elite insiders of the sport hold that honor almost in mockery, a privilege which is theirs to hoard. A man like Igaguri cannot exist in Joe's Japan of the 1970s -- in this update and critique of sports manga past, sport itself is class struggle.

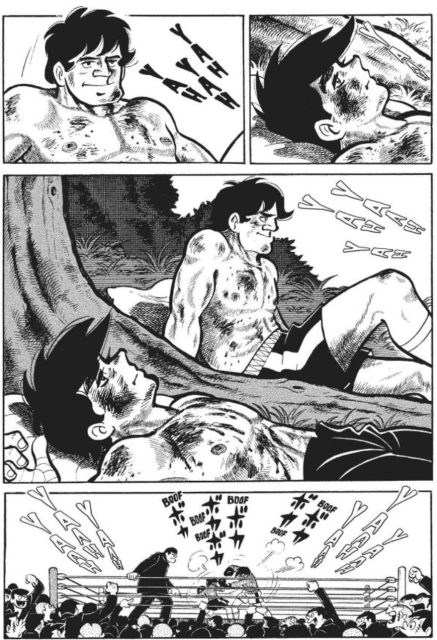

Joe is a man who lives by rules of his own making in a battle against the rules of the powerful. And yet, Joe is not an individualist hero. In prison, Joe's rivalry with Rikiishi, another young boxer already on the pro circuit, is not only a conflict with a young man slightly closer to the traditional route to success, but also a performance the grace of which inspires his community of fellow prisoners to elevate their own conflicts to the ring, more dignified structure of play. Whether among the young prisoners in juvenile detention or the children of the slums, Joe's greatest strength is that he builds community around himself, but all Joe sees is his own desperate fight, for survival, for excellence -- he does not yet see that he is an inspiration. Is Joe's tomorrow to live another day, or is it our tomorrow, our universal liberation?

Joe is a man who lives by rules of his own making in a battle against the rules of the powerful. And yet, Joe is not an individualist hero. In prison, Joe's rivalry with Rikiishi, another young boxer already on the pro circuit, is not only a conflict with a young man slightly closer to the traditional route to success, but also a performance the grace of which inspires his community of fellow prisoners to elevate their own conflicts to the ring, more dignified structure of play. Whether among the young prisoners in juvenile detention or the children of the slums, Joe's greatest strength is that he builds community around himself, but all Joe sees is his own desperate fight, for survival, for excellence -- he does not yet see that he is an inspiration. Is Joe's tomorrow to live another day, or is it our tomorrow, our universal liberation?

Two men walk away from a police station. One is kicking and screaming. That's our Joe. The other, Nishi, a large stout man with a firm countenance not unlike Igaguri's, offer's Joe his hand. Joe shoves it away. But the two men walk together, side by side, their backs melting into the night, inky darkness lit by the smeared white glow of streetlamps. The harsh haze of city lights illuminates the street behind them, the dirt road, the expanse of Tokyo seen at ground level. This is a brutal city, a dirty city, an immense city, but the city is alive by Tetsuya Chiba's pen and Asao Takamori's script. There's a fight on, staged between the city and her slums, it begins tomorrow.

The post Today’s Fight Starts Tomorrow: Ashita no Joe appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment