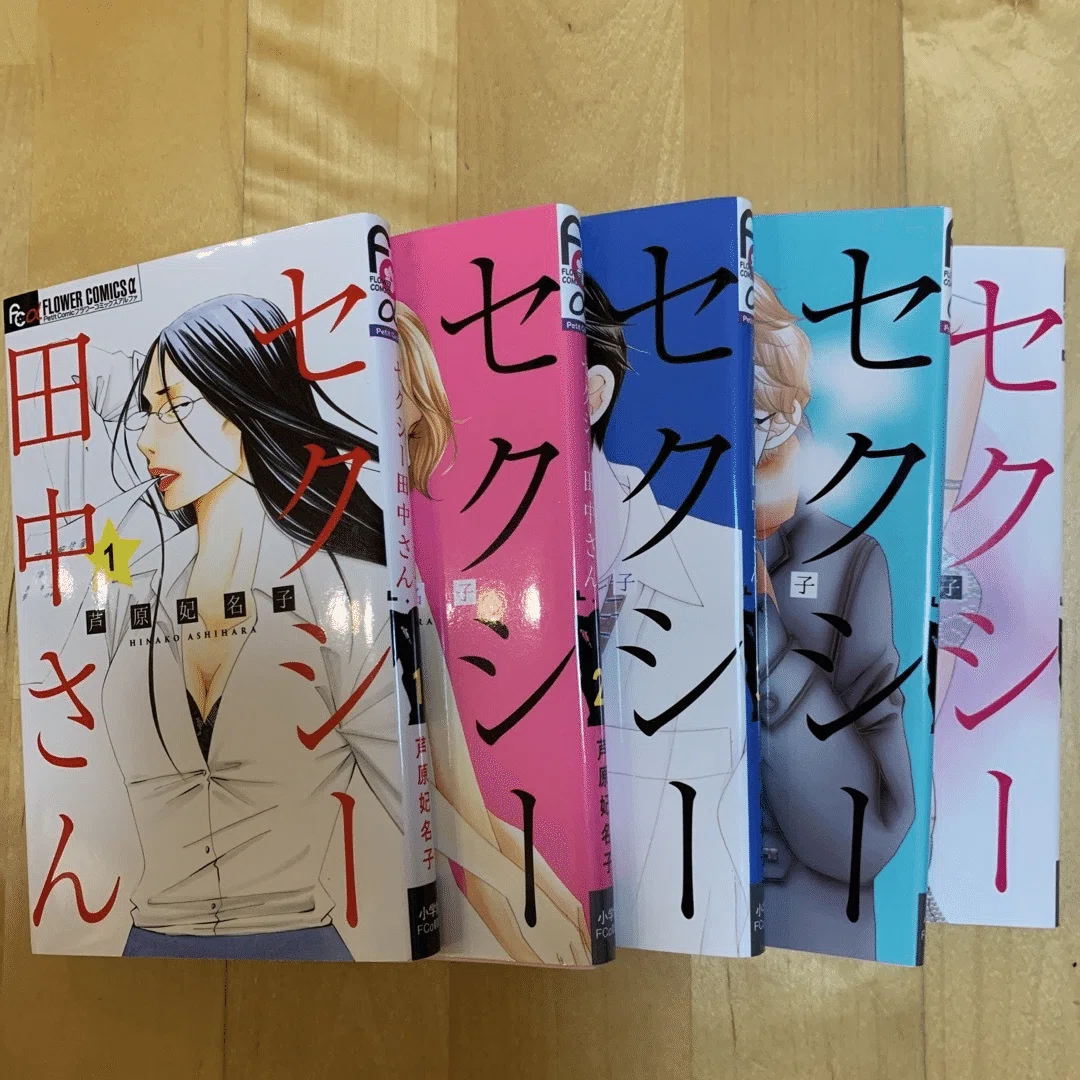

In January 2024, a controversy erupted in Japan surrounding the final two episodes of the TV adaptation of the manga Sexy Tanaka-san. What began as a disagreement between the screenwriter and the original manga creator — both women, incidentally — over creative direction on social media eventually escalated into a national scandal, culminating in the tragic suicide of Hinako Ashihara, the manga’s creator.

In the aftermath of the incident, I soon found myself considering how to present the tragedy to an English-speaking audience, as a manga researcher living in Japan. My first instinct was to frame it as a Japanese counterpart to the Alan Moore's conflicts with Hollywood — an auteur standing against the commercial adaptation of their work. However, the more I researched, the clearer it became that such a comparison, while superficially appealing, ultimately obscures more than it clarifies.

I discarded my initial draft and began again. After all, even now — some more than a year after her suicide — Japan has yet to produce a satisfying or convincing public account of what happened. I hope this piece will serve as a modest first step toward a broader study that will examine Sexy Tanaka-san’s tragedy, not merely as the result of a single conflict, but as the outcome of multiple, overlapping tensions — structural, personal, ethical, and gender-related.

Ms. Tanaka, the Clark Kent of Japanese working women

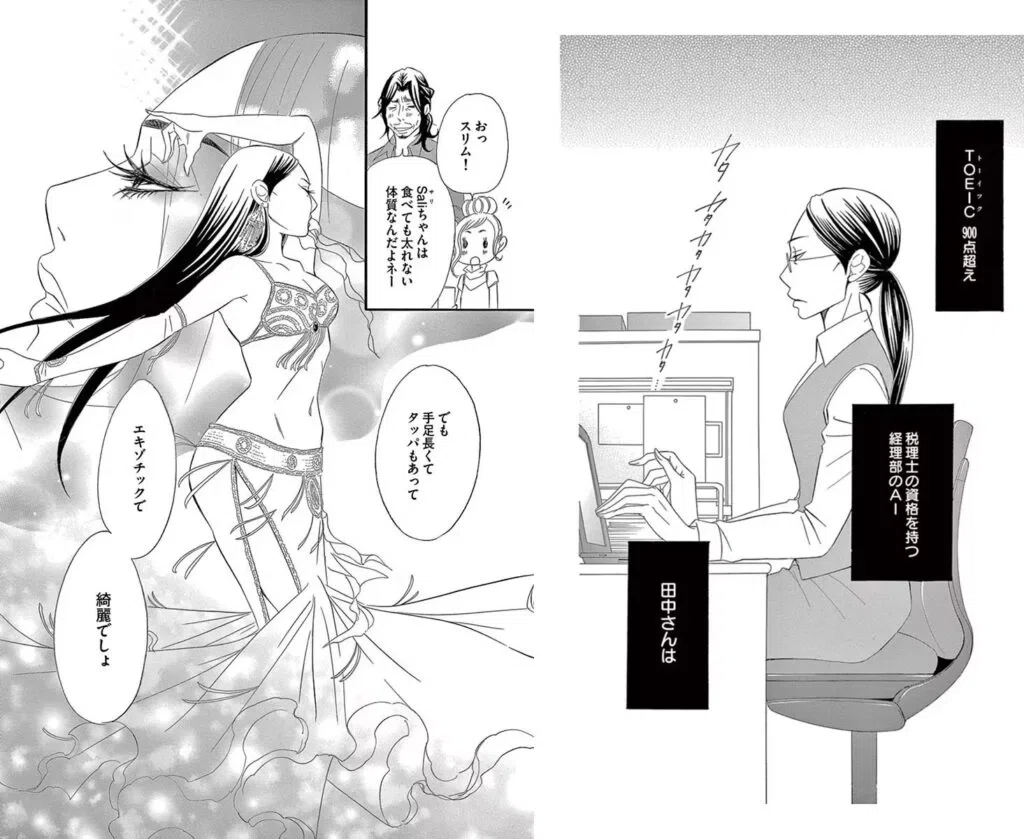

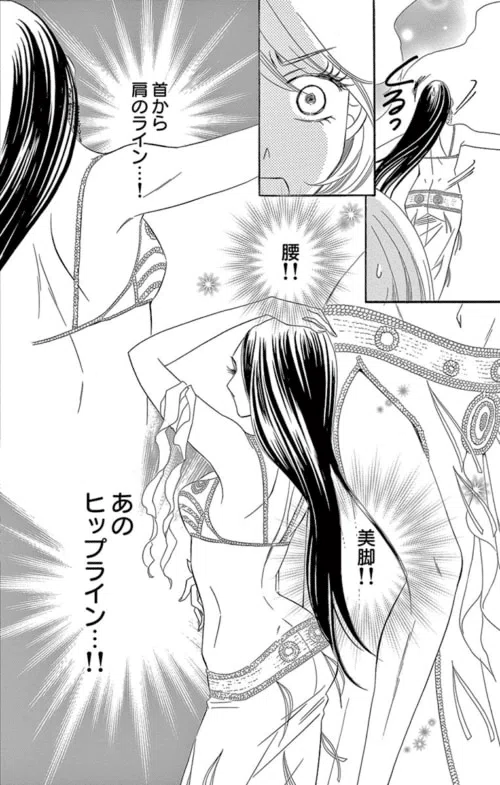

Sexy Tanaka-san is a story based on a real-life 40-year-old woman named Tanaka, an unremarkable office worker on an irregular contract who, by evening, transforms into a glamorous belly dancer. Comically told from the perspective of a much younger female colleague in the same office, the story follows Tanaka’s striking double life across these two contrasting worlds.

The narrative bears a resemblance to the American superhero Superman’s double identity. Just as Superman balances his ordinary persona, Clark Kent, with his heroic role, Tanaka navigates between her conventional daytime self and her vibrant nighttime alter ego. Seen through the eyes of her junior colleague, her story becomes a subtly comic yet poignant portrait of the inner conflicts many modern Japanese women face, torn between societal expectations and personal desires.

What happened and why it mattered

In mid-2023, Nippon Television Network announced that it had secured the rights to adapt Sexy Tanaka-san — the ongoing manga serialized in a women’s monthly magazine — into a television drama. Though the original story was bright and amusing, the adaptation gradually strayed from that playful tone. On the day the final episode aired in December 2023, the screenwriter made a surprising statement on Instagram: she revealed that she had written episodes 1 through 8, but that the final two episodes — 9 and 10 — had been scripted by the manga's author, Hinako Ashihara. According to the screenwriter, this had not been part of the initial plan and constituted “an unprecedented situation” that left her confused and, evidently, frustrated.

About a month after the screenwriter's statement, Ashihara posted a detailed response on her blog. In it, she apologized to viewers for the confusion and explained her decision to write the final episodes. She stated that, from the beginning of the adaptation process, she had made it a non-negotiable condition that the series remain faithful to the manga. If deviations were necessary, she expected to be the one to rewrite or approve them. These terms had been clearly communicated to Nippon TV, the network producing the show.

However, Ashihara wrote, the scripts submitted for each episode repeatedly ignored those conditions. She was forced to revise or rewrite them to align with the original narrative and tone. Even in the final stages, the scripts for episodes 9 and 10 significantly diverged from what had been agreed upon. With production deadlines looming and her requests for a screenwriter change denied, she took it upon herself to write the last two episodes under extreme time pressure and while still managing her ongoing manga serialization.

The backlash came swiftly. While Ashihara had taken care to describe the process as factually and respectfully as possible, her public statement resulted in a torrent of online criticism — this time directed at the screenwriter, the producers, and other members of the TV staff. Within two days, Ashihara deleted her blog and most of her social media posts, leaving only a short message: “I didn’t mean to attack anyone.”

Then, on Jan. 28, 2024, Ashihara was reported missing. She had left Tokyo, and a search was initiated in cooperation with Tochigi Prefecture police. The following day, her body was found at the Kawaji Dam in Nikko. A note resembling a suicide letter was found at her home. Media outlets reported the cause of death was suicide. The conflict had become a national topic, covered widely in mainstream media.

Above is the Nippon TV news report from Jan. 29, 2024, on Ashihara being found dead.

Alan Moore’s choice: Protest by refusing to participate

Alan Moore is perhaps the most famous example of a comic book creator in the U.S. who has publicly rejected adaptations of his work. In multiple cases — most notably Watchmen and V for Vendetta — he demanded that his name be removed from film credits, refused royalties, and declined any involvement with the production process. His stance was not passive withdrawal, but an active form of protest: a refusal to legitimize what he saw as the distortion of his original intent.

For Moore, maintaining ethical authorship meant stepping away. He chose to protect his vision by severing ties with the adaptation entirely. In doing so, he framed his refusal not as abandonment, but as a way of defending both the integrity of the work and the autonomy of the creator. This position, while rare, has become legible within Anglo-American media cultures, where creator-producer tensions are recognized and even expected in the adaptation of intellectual property.

In the Anglo-American comics industry, rights to characters and stories are typically signed away early in a creator’s career. What remains, often, is the symbolic authority of the author’s name — a name that can be withdrawn as a form of protest.

(Note: I know that Moore’s stance is rooted in a far more complex web of ideological commitments than I can address here. This essay focuses instead on the specific contours of Japanese authorship and the ethical weight borne by manga creators within Japan’s media ecology.)

Hinako Ashihara’s choice: Engaging to protect the work

In contrast to Alan Moore’s refusal to engage, Hinako Ashihara chose — indeed, felt compelled — to step into the adaptation process. In Japan, the original manga author typically retains the final authority over whether an adaptation can proceed. Depending on negotiations between the publisher and the adaptation producers, the author may also take an active role in the adaptation process. However, due to the demanding nature of serialization, they rarely have the time or capacity to do so in practice, with the editor in charge often handling supervision on the author’s behalf. When her manga Sexy Tanaka-san was adapted for television, Ashihara initially expressed a willingness to leave the screenplay in the hands of a professional while supervising it. However, as the script began to diverge from the emotional and narrative core of her original, she became increasingly concerned.

Ashihara was not a passive bystander to the adaptation of her work. She entered the process out of a desire to protect her characters — not simply as intellectual property, but as extensions of herself. Eventually, she took the unusual step of writing the scripts for the final two episodes herself. What began as a TV adaptation became a crisis of authorship. When creative tensions spilled onto social media in January 2024, several months after the TV drama ended, the conflict quickly escalated into a public controversy, culminating in Ashihara’s disappearance and, days later, the discovery of her body.

Where Moore chose the path of publicly walking away to preserve his dignity, Ashihara felt she should not. In Japan, to refuse involvement in order to preserve one’s creative dignity is not always seen as an ethically neutral act. It can feel like a betrayal, to both the fans and the original author. Her death shocked the Japanese public, not only because of its tragedy, but because it exposed a deep vulnerability in the structure of Japanese media production, particularly the ethical burden placed on manga creators when their work is adapted into other forms.

Character distance, cultural divergence

At the heart of this divergence lies a cultural and commercial difference in how creators relate to their characters. In the American mainstream comics tradition, characters often exist independently of any single author. They are meant to be inherited, reimagined, and reshaped by successive generations of writers and artists. The creative relationship tends to be one of stewardship — temporary, professional, and bound by contract.

In Japan, by contrast, characters are more often seen as inseparable from the authors who create them. Manga artists frequently speak of their protagonists as extensions of their own emotions, identities, and life experiences. It’s not unusual to hear a creator say, “He or she is part of my personality.” That bond is not merely metaphorical; it is visceral, rooted in a creative process where the author writes, draws, and lives with the character over many years, often in solitude.

This difference is not simply a matter of sentiment. It reflects a distinct production model in which manga creators — especially those serialized in major magazines — retain both legal and moral authority over their work. Unlike in the U.S., where corporate IP logic prevails, the Japanese manga industry operates on the principled premise that character and creator form a continuous, indivisible authorship.

While long considered a peripheral stream within the manga industry, especially in comparison to mega-franchises like "Dragon Ball," manga aimed at female readers began to gain greater cultural standing from the late 1980s onward. This shift was catalyzed in part by television. As networks increasingly turned to josei and shōjo manga as source material for contemporary, urban dramas, these works came to be seen not only as entertainment but as meaningful reflections of modern life. With this rising visibility came a reevaluation of their creators — most of them women — as artists whose characters carried emotional nuance and social insight that television dramas sought to harness. (Some even went so far as to receive an Eisner Award in the United States!)

This helps explain why Ashihara felt compelled to intervene. She wasn’t overstepping her bounds, she was honoring them. To her, the characters in Sexy Tanaka-san were not merely assets to be protected, but persons to be defended.

Another author at work

Ashihara, especially disappointed with the completed scripts for the final two episodes of Sexy Tanaka-san, chose to discard them and write new ones herself — an act that met the terms of adaptation but was still a transgression. She unintentionally challenged a professional boundary that has grown increasingly sensitive in Japan’s media culture. To understand the full weight of that act, we must look more closely at how the figure of the screenwriter, especially female ones, has evolved within Japanese television drama.

For decades, Japanese scriptwriters stood as the invisible narrators behind the golden age of serialized TV drama — indispensable, yet rarely acknowledged by name. The era did produce quite a few writers, both men and women, who gained real prominence and admiration for shaping the tone and texture of contemporary storytelling, though most continued to work outside the spotlight.

That began to change in the 2000s and 2010s, when social media enabled screenwriters to develop visible profiles and loyal fanbases. As audiences grew more attentive to who was writing their favorite dramas, scriptwriters — especially women — began to carry increasing marketing weight. In series centered on female protagonists, a well-known female writer became a strategic asset: her name signaled emotional credibility and helped draw in female viewers seeking stories that reflected their own experiences.

Behind the female-versus-female narrative

There’s a well-worn Japanese saying — sometimes invoked jokingly — that “a woman’s worst enemy is another woman.” When the dispute between the female screenwriter and the female manga creator of Sexy Tanaka-san became a trending topic on Japanese social media, some might have recalled this phrase with a knowing smirk. But to reduce the conflict to gendered rivalry is to miss the deeper, systemic fault lines that animated the tragedy.

At its core, this was not merely a clash between two creative egos. It was a collision between two distinct professional cultures: that of the screenwriter and that of the manga artist. Screenwriters, not only in Japan but worldwide, usually focus primarily on crafting the narrative structure and emotional flow of television dramas. When skilled or prominent actors are cast, the characters begin to take on autonomous life through their performances, allowing the screenwriter to concentrate even more on the narrative itself. In contrast, manga artists are character-centric. Because manga characters lack a physical presence, their creators invest tremendous effort into shaping their personalities and identities. This painstaking character development is essential to bringing emotional depth to the story.

In this sense, the manga creator’s dissatisfaction with the way her characters were portrayed in the drama was not unusual. Many creators harbor frustration when adaptations fail to align with the clearly defined personalities and character traits they have established for their protagonists. What was unusual in Ashihara’s case was her decision to act. Manga creators might be given the right to request changes to adaptation screenplays, but what was unusual in Ashihara’s case was her exercising the right to claim full control over a completed script by discarding it and personally rewriting it. Backed by her publisher (which, unlike in the U.S., also serves as a de facto agent), she penned the final two episodes herself.

That act, while legally permissible, was perceived as a professional breach. It unintentionally wounded the pride of the screenwriter, who later voiced her dissatisfaction online—joined by another industry colleague as well as her fans. The backlash that followed drew attention, leading Ashihara to respond on her own blog. What followed was a spiraling flame war, fueled by social media algorithms and public voyeurism. What began as a creative dispute became an ethical battlefield—and both Ashihara and the screenwriter were left to absorb its full weight.

The Aftermath and the Limits of Introspection

In the wake of Hinako Ashihara’s tragic death, Japan saw an outpouring of commentary across various media platforms. Voices from active manga artists, cultural critics, and industry insiders filled newspapers, television panels, and online forums. Several months later, the television network responsible for Sexy Tanaka-san’s adaptation and the manga’s publisher each released independent investigation reports, detailing the circumstances that led to the public dispute and its devastating outcome. Yet, for all their detail, these responses, whether heartfelt or procedural, felt curiously unsatisfying, like scratching an itch through a thick layer of cloth. Above all, the manga artists themselves, for all their commentary, seemed visibly at odds with their own ambivalence — an unease that seeped through every pause and between every line.

What was missing, it became increasingly clear, was a perspective from outside Japan’s media ecosystem. The Japanese system, with its deep respect for the manga creator’s authority and its intricate web of professional obligations, is so tightly woven that it can be difficult to see its fault lines from within. The investigations, while thorough, were conducted by stakeholders embedded in the same cultural and industrial framework that shaped the tragedy. They could identify missteps — communication breakdowns, lapses in professional courtesy — but they struggled to question the deeper assumptions underpinning the system itself.

This absence of an external lens mirrors, in a curious way, the reception of Alan Moore’s protests in the Anglo-American context. Within the U.S. and U.K., Moore’s decision to disavow adaptations of his work is often celebrated as a bold defense of artistic integrity, a middle finger to the commodification of creativity. Yet, to those unfamiliar with the American comics industry, where creators routinely surrender control to corporate publishers, a situation dating back to the “Superman's Original Sin” of 1938, his stance might seem perplexing, even indulgent. “If you don’t like it, why not just refuse the adaptation?” they might ask.

The answer lies in the specifics of the system Moore was resisting, just as Ashihara’s tragedy can only be fully understood by stepping outside the norms of Japanese media production. Aware of my own difficulty in articulating this, I have written the above in English to retain some distance — as an outsider — while speaking of that painful event. I present this to what I consider the most trusted comics criticism journal in the English-speaking world, rather than to any domestic Japanese outlet. If given the opportunity, I would like to revisit the subject in a more considered essay someday.

The post Who Killed Tanaka-san? The Tragedy Behind a Superwoman’s Smile appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment