The comics direct market as we know it today had many fathers and mothers, and many moments of birth. Here is one that never happened, but almost did: At the end of 1973, longtime convention organizer, comics and art dealer, and budding entrepreneur Phil Seuling made a long-distance call from his home in Brooklyn to that of his friend Bud Plant in San Jose, California.

Seuling was coming fresh off a deal he had struck with three of the largest mainstream comics publishers — DC, Marvel, and Archie — to distribute their books at a steep discount and on a nonreturnable basis directly to specialty bookstores and comic shops. Seuling, whose connections tended to be limited to dealerships in the Eastern half of the country, wanted to entrust Plant with the role of sub-distributor on the other side of Rockies: in effect, Seuling and Plant would carve the comics kingdom in two at the moment of its birth.

But Plant said no: his sights were set elsewhere, as they always had been. Born in San Jose in 1952, Bud Plant grew up alongside the Bay Area comics scene. Weaned on Carl Barks, graduating to Jack Kirby, his first passion had always been for the simple thrill of collecting things and showing them off. Like his contemporaries Chuck Rozanski and Buddy Saunders, Plant gravitated toward the early fanzines like G.B. Love’s Rocket’s Blast Comicollector, through which he placed the first ads that evolved into a proper mail order dealership: the eponymous Bud Plant, Inc.

One thing led to another. Bud Plant, Inc. acquired a hefty enough backlog to make viable a series of physical storefronts, among the very first dedicated comic shops in the United States: Seven Sons Comic Shop came first, in his hometown of San Jose, then Comic World on the other side of town. And then — in Berkeley, and in partnership with co-founders John Barrett and Bob Beerbohm — the shop that would become most associated with Plant’s name over the years: Comics and Comix, its name nodding to Plant’s newfound discovery of the underground comix scene that was coming to a head right across the Bay in San Francisco. By the mid-70's, Comics and Comix had become an honest-to-God local chain, operating four locations in San Francisco, Berkeley, San Jose, and Sacramento.

At the end of the ‘60s, Plant and his partners took advantage of the evolving distribution system for underground books (through which sales were made directly to specialty shops without going through the notoriously difficult and unreliable network of newsstand distributors) to become one of the seminal early figures in independent comics publishing. Following closely in the footsteps of Wally Wood’s Witzend and Mike Friedrich’s Star*Reach, Comics and Comix became both publisher and distributor for titles like Tom Bird’s Barbarian Killer Funnies and Jack Katz’s The First Kingdom — never financial hits, but notable in their day as pioneers in what would soon enough lead to Cerebus, Elfquest, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and the bewildering future they spawned.

Meanwhile, Plant himself was increasingly becoming a fixture on the national circuit of comics conventions that was just then taking shape, and which were providing both a convenient means to acquire and deal in new collections, and making him something of a niche celebrity among comics aficionados. In 1974, he organized one of his own: the semi-legendary Berkeley Con, which in cultural memory came to be seen as a kind of high noon for the Bay Area underground scene just before it faded away into boomer oblivion.

Given Plant’s reticence to partner with Seuling in the more prosaic business of comics distribution, it’s ironic that by the early 1980’s, Plant found himself deeply ensconced in the business despite himself. By then, Seuling’s one-man monopoly on the direct market had been broken through legal action, and replaced by a growing number of competing distributors and sub-distributors jockeying for contracts in comic shop markets. Out of necessity and convenience, Plant began sub-distributing for various regional distributors with whom he did business for his comic shops, and when those partners fell on financial hard times, Plant’s best option was simply to absorb their companies whole. The result, to make a long story extremely short, was that by the end of the 1980s, Plant had belatedly become the uncrowned king of West Coast comics distribution without really trying. Like the British used to imagine about their dominions, it was an accidental empire.

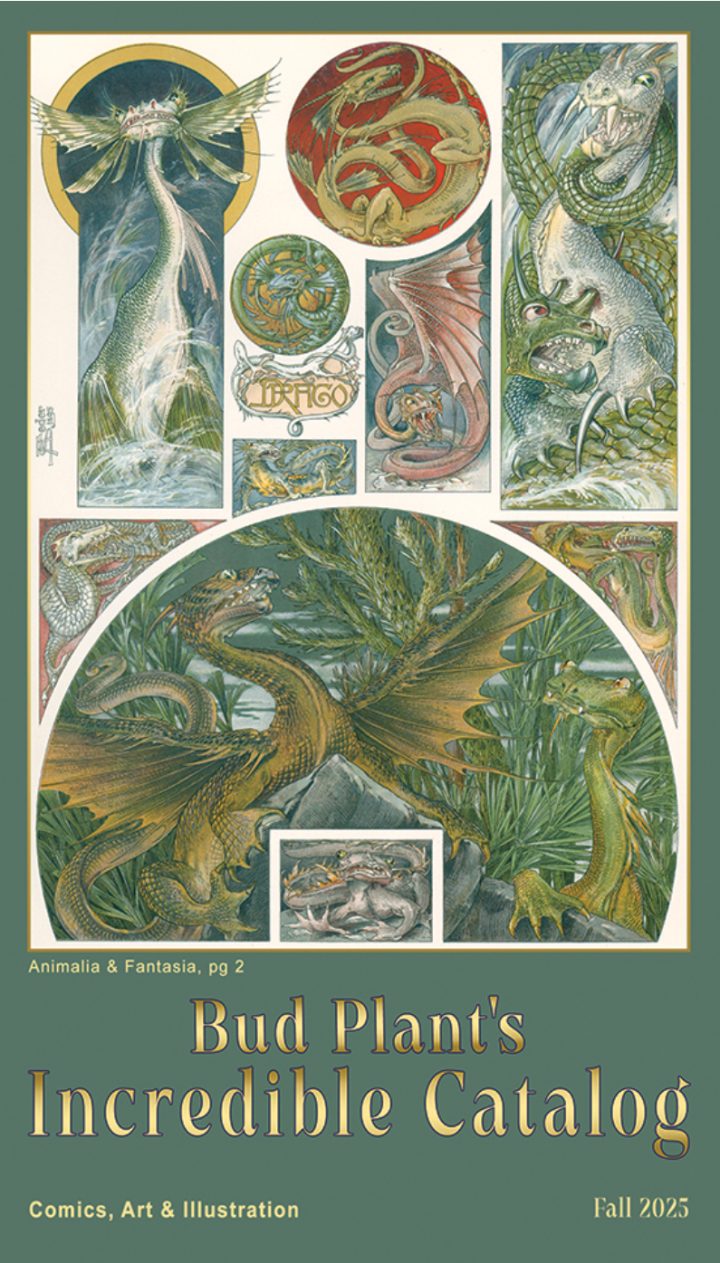

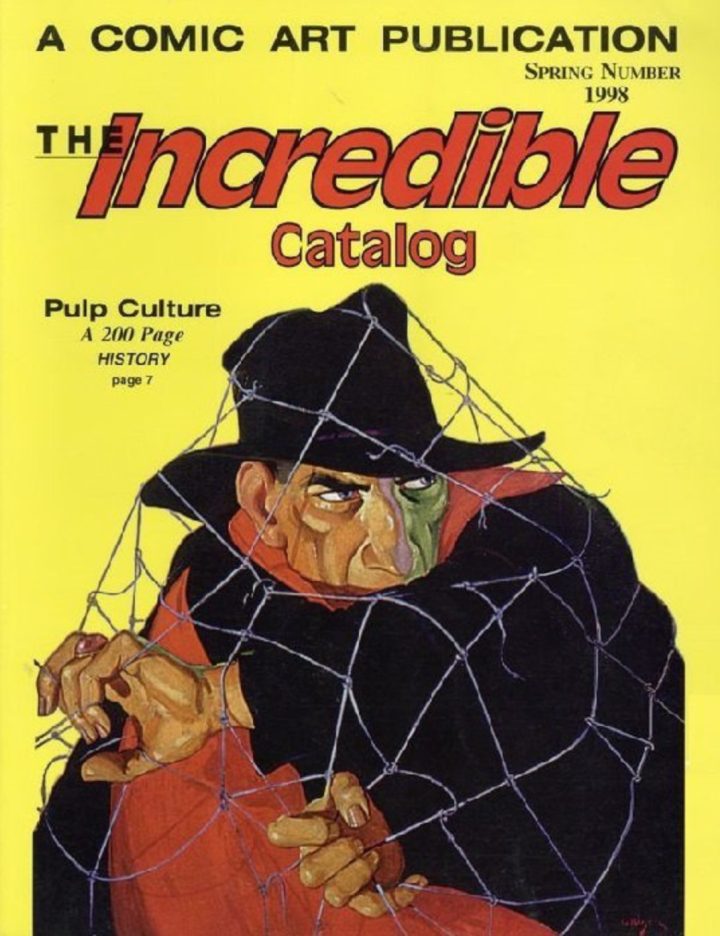

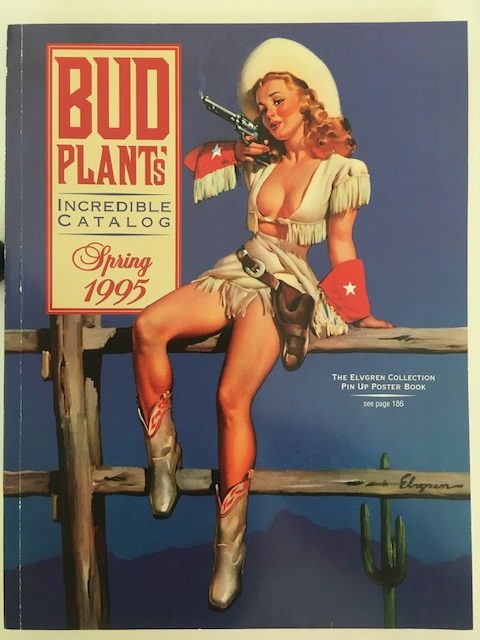

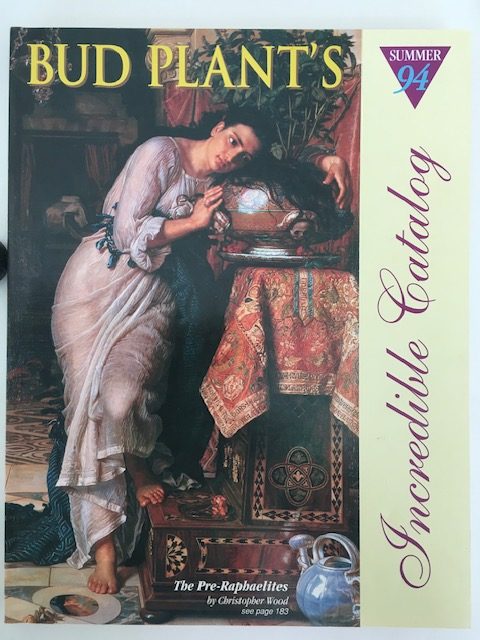

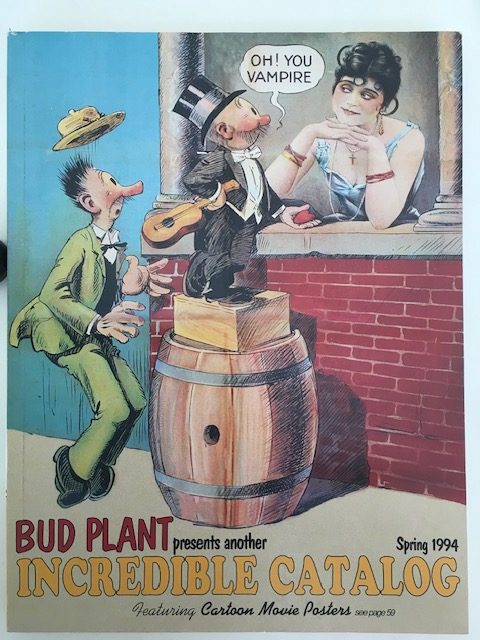

And almost as soon as it started, it was over: in 1988, facing mounting debts of his own, Plant cashed out of the distribution business, selling everything off to Steve Geppi and Diamond Distributors, then in the process of assembling a very deliberate national empire of their own (of Geppi and Diamond’s own fate, we need only say sic transit gloria). Plant decided to return to his roots, putting out the curated and artfully designed mail order catalog that has continued to bear his name for the past four decades.

So when Plant casually announced, in the pages of that same catalog this past June that he was “retiring — sort of — in 2026,” it came … not as a surprise, exactly, since there are more surprising things on this earth than a 73-year-old man managing to successfully retire. But certainly as a melancholy, if inevitable, bit of news. So long to the early days of comics fandom and fanzine trading. So long to Seuling Con, and Galaxy Con, and Berkeley Con, and the glory years of San Diego. So long to Jack Katz and Tom Bird. So long to direct markets and belly-up distributors. Bud Plant is calling it a day.

On a sultry holiday weekend in July, Plant spoke with me from his home in San Jose about the long story of his time in comics. The following interview was trimmed substantially for length, so as not to try the patience of even the connoisseur readers of The Comics Journal, but not for content.

ZACH RABIROFF: So, how are you doing, Bud?

BUD PLANT: Not too bad. It's a holiday weekend. How bad can it be?

Well, that question is like a dare in America right now, isn't it?

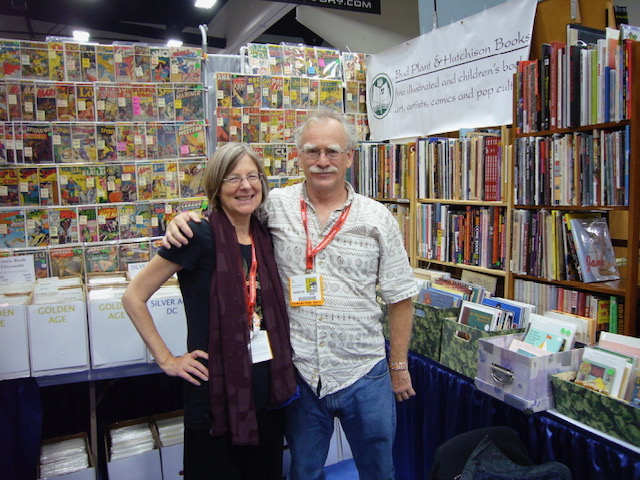

Oh, well, that is true. Don't get us started on politics. I'm reading the news a little less than I used to. But we're doing good. I got no complaints. At 73, my partner Ann and I have been together for 23 years now, and we're both going to the gym. We're staying in shape, and I can afford to keep supporting myself in the style that I've become accustomed to, which is mostly continuing to buy old comics and interesting books. So that's a good thing. My business could be doing better, but oh well. At the moment it's still feeding a few people, and maybe I'll make something happen and keep going. That's my big thing right now.

Maybe we could go back and talk about how you got here, because it's been a long and interesting course of events. You were born in 1952. Are you from San Jose originally?

Yeah, east San Jose. My parents settled there right after the war. They both served in the U.S. Army. They were both First Lieutenants, and they actually wouldn't have met if not for the war. They met on a troop ship going to North Africa, and they came home and built a house in San Jose in ‘46. I've got two sisters that are older than me.

What was it like growing up?

It was pretty classic fifties stuff, man. What you read about. Buying Cokes for 10 cents and comics for 10 cents, and picking up pop bottles and cashing them in for 3 cents and mowing lawns. I mean, we were on the edge of San Jose, so it was pretty close to being the idyllic sort of environment with lots of families, and a couple kids, and get togethers on the street and sidewalks, and that sort of thing. It was a pretty good childhood back in the day when you could get on your bike and disappear from home for 12 hours and your parents wouldn't freak out about it.

And, I would assume in your case, buy comics with your allowance money.

Exactly. I mowed lawns for a couple of little old ladies, and for my grandfather. I made very little allowance from my own parents, but I did a lot of yard work and got hooked. Boy, did I find the right comics in ‘61. I read Fantastic Four #1, and one of the Brave and the Bold tryout issues with Joe Kubert doing Hawkman. I mean, just great stuff in ‘61.

So you were gravitating toward the acknowledged classics even then?

Yeah. I don't know what made me jump in at that point. My parents had a subscription to Walt Disney's Comics and Stories, and my dad always appreciated comics. We all read the daily newspaper strips and the Sunday paper, but he wasn't a comic book buyer per se, and in the war he wasn't buying comic books in North Africa.

In ‘64, when I would've been just 11 or 12, I suddenly discovered Marvel, and I became a Marvel Zombie for a little while. I graduated into DC and all the rest of the stuff. But that's when I really got totally addicted to comics. In early ‘64.

You were in the Merry Marvel Marching Society according to the published lists in those comics.

Yep. My name was the very last one in Fantastic Four #40, but I think I had changed my name by then. I was Buddy Plant when I was younger, and about that time I had changed my name to Bud Plant, so I think it's “Bud Plant, San Jose, California.”

I got into the mail order business starting around ‘70, and I just used my name. People didn't make up names for businesses back then. I was just some guy selling underground comics, so I just used my name. By the time I thought about it, I thought, I could have been Mile High Comics or Million Year Picnic or something real sexy and groovy. But a lot of people knew me by then. I'd been going to shows and sending out comics for a while, so I decided to just stick with the name.

You’ve had all of these other shops and company names that existed under you, but it's always been sort of the Bud Plant brand that's hovered above it.

That is true. Comics & Comix was the first major set of stores I was involved with. That was a partnership. In fact, Comics & Comix started out with some silly names. We were imitating what Phil Seuling had done. He called [his convention] the New York Comic Art Convention, and we said, “‘Comic art’, that's really cool.” So we [opened] the Berkeley Comic Art Shop and the San Francisco Comic Art Shop and the Palo Alto Comic Art Shop. Really stupid — you want to brand a number of stores with the same exact name. But fortunately, we got smart fairly early. Bobby London had done a logo for us that read, “Comics & Comix” with the X and the C on our Berkeley shop, and we said, “Duh, let's just call ourselves Comics & Comix.”

And that was a reference to the two halves of the industry by that point: the underground ‘comix’ with an X, and the overground “comics” with a C.

Absolutely. The shop in Berkeley was four blocks down from the entrance to the University of California, Berkeley. It had at the time 30,000 kids or something going there. And so that was the place to sell Zap Comix and the whole nine yards. We were the hip shop at the right time and the right place.

Tell me about what the comics culture and the comics scene was like in the Bay Area in those days.

Well, man, back when we first opened our first store, it was Seven Sons Comic Shop. It was six of us, technically.

Can you explain that name? It's Seven Sons, but there were six partners.

Well, the joke was that we had an honorary member, and he was working at some outfit, and he used to steal office supplies for us. That's the story. I don't know how much truth there is in that, but that was a guy named, I think, Al Castle who was part of our little group. But we had six guys.

We’ll print the legend because that's a good story.

There you go. Yeah, we had six guys, but somehow Seven Sons sounds one hell of a lot better than Six Sons. That almost sounds like Saxons. We don't want that.

Whereas Seven Sons, it's somehow biblical.

Yeah, there you go. We had six guys, and we all contributed, I think, 35 bucks apiece, and the rent was, like, 75 bucks a month. And Jesus, these guys rented us a store! Although we did have a couple guys that were over 21, I was, like, 14 or something. We had a guy whose mom was really interested in him getting a job. He was kind of a loafer, and he was about 24; he's the guy that took over the shop eventually. Even Michelle Nolan was part of it. She would've been 18 or 19, she was in college, so she was an adult. I think she signed some of the documents. Most of us were too young to sign anything.

Fourteen years old and opening up a shop.

Well, yeah, but we were a group, and the age didn't matter that much. I mean, if you were into comics, you could be 14 or you could be 20, and it wasn't a huge gap. It's not like dating girls or something. My closest buddies who were partners in the shop were all on the other side of San Jose, so my mom had to take me over to visit them before I got a driver's license. And even after that, one of the guys that would have a car would come over and pick me up and take me over for our little weekly meetings at one of the guys' houses. You could count all the collectors in San Jose on … well, maybe there were 15 guys that you could actually name that were all part of early comics back then. Some of them were actually publishing fanzines, but others of us were just high school kids.

Had you connected through fanzines? Is that how you all met in the first place?

Yes. I'd say overall, that's probably true. My story, which I've told a bunch of times, is that a guy accosted me outside of a used bookstore that sold comics. He saw I was interested in comics and he says, “Hey, I got some buddies and we're into comics. Are you into comics?” And boom, that was my opening to latch onto these guys. Before that, it was just me and a couple of guys in my high school that happened to be interested in comics. We were, at that time, avid Marvel fans, but we didn't know anything about fandom at that point in time. That was actually a little bit after all the promotion of [Jerry Bails and Roy Thomas’ seminal fanzine] Alter Ego, and the fanzines in the very early days, in the back pages of DC comics, for instance. I hadn't seen that, but once I met this guy and went over to John Barrett's house and they said, “Here's the Rocket’s Blast [another early fanzine, founded by Buddy Saunders]; you can buy old comics.” These guys had advertised stuff and boom, oh my God, a world suddenly blossomed.

Back before that, there just wasn't much. There was Michelle Nolan: I think the story on her is that she actually advertised in one of those ‘wanted’ things in the newspaper and said, “I want to buy comics.” I think I actually met her through that.

Just an old fashioned classified ad.

Exactly, yeah. And also there was the San Jose flea market. I met a couple other people because I was hanging in the San Jose flea market looking for comics. At that point — this is ‘64, ‘65 — comics were a nickel. If you buy a comic at the theme market, it's used and it's a nickel. That's it, period. So it was a cheap way to get a lot of good entertainment.

At what point did it transform for you from a cool way to connect with other fans and into something you could actually do to make money?

Well, I think, honestly, I really compare it to being hooked on drugs. Which I never was, but I've always been hooked on comics and I really still am. I think we opened the store mostly just to get more comics. We weren't really trying to make a living or anything out of it. We were all just students. Michelle was in college, and John and Jim and I were all in high school, and there was another guy, Tom Tallman, who probably was just starting college. We were all really interested in comics, and we said, “Let's open the store and we will sell some comics and see what happens.”

Obviously a lot of stuff would come in through the door. And at that point, all the articles on comics being valuable — which were plentiful a little later on — hadn't come out. People were coming in with a box of pulps and a box of comics and stories, happy to have us pay them a nickel or a dime, 15 cents a piece.

So it was really just about the excitement of getting to be around all those comics.

Yeah, yeah. We basically would take the money and turn it back into comics. What happened, unfortunately, is that if good stuff came in, we'd all sit there and play cards to get first pick, and we'd take all the good stuff home. We all collected Carl Barks. Somebody comes in with a whole bunch of Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck, and we shuffle a bunch of cards, literally, and see who gets the first pick. The very best stuff was getting creamed right out of the store instantly.

Were you familiar with other shops when you first opened up Seven Sons?

The only other shop we would be aware of at that point was Cherokee Book Shop, which was a traditional used bookstore [that also became a well-known retailer of vintage comics]. This is in Los Angeles, or actually Hollywood. That's the only shop that we would have known about at all. Collectors [Bookstore, another Los Angeles shop], I think at that point was still really small. I went to Collectors in ‘67, it was off on a side street, and it was a fairly small store. They were selling ECs for a buck apiece or something. Other than that, it would've only been conventions. And nobody went to a convention in our group until ‘67.

How were you getting the comics that you were stocking in the shop? Because this is obviously well before what we would come to think of as the direct market.

That's the shortsightedness of us, because we didn't carry new comics. All we carried were used comics and used paperbacks, and we'd have a box or two of used LPs, because at the time we were talking about the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and all the psychedelic music.

We were picking those up, but that's it. We were a funky, used thrift store that just happened to be specialized in the comics area. I don't think we even considered going to the distributor to try and talk our way into getting new comics. There were two distributors in the area. One was in south San Jose and then the Gilroy area. They would put the comics out a little earlier, so we'd drive down halfway to Gilroy, which is 10 miles or so, and pick up a bunch of the comics – I think they were 15 cent cover price at that point, and we'd bring them back and sell them for 20 cents. That was as sophisticated as we were.

Were you managing to get it from the wholesale distributors as well?

No, we were buying those off the newsstand. We never had a relationship with a wholesale distributor until 1972 when we opened up Comix & Comics in Berkeley. Before that, the two stores we had were strictly used merchandise. Bob Sidebottom, who became a competitor in San Jose and opened the Comic Collector Shop, was older than we were. He was in his thirties. Smart guy — he has a mixed history, but he was a fairly smart guy, and he saw that we were doing well, and there was a market for this stuff. He was interested in doing it, too. He'd been working for a record shop at the time, and he's probably the first guy in the San Jose area that actually started bringing in new comics, actually making a deal with a distributor and buying them at whatever the discount was back then. I think they were all 30% off and returnable if you were buying from the distributor. And it wasn't until Phil Seuling came along that everybody could start getting exactly what they wanted.

But by then there had already been the beginnings of a different model of distribution because of the undergrounds. When did you first encounter the underground stuff?

I first encountered it probably with Zap #1. One of my buddies, a slightly older guy, had somehow gotten to know [Zap cartoonists Robert] Crumb and Spain [Rodriguez] and some of the guys in San Francisco. He was just a hardcore comics guy. This was Al Davoran, and he became one of my co-editors on Promethean Enterprises, our fanzine that we did. But Al said, “Go down to recycle books and pick up a copy of this Zap comic. It's pretty cool.” And I picked it up — this is either ‘68 or ‘69 — and it was all Crumb stuff, and I really didn't get it. I mean, Crumb was coming from a completely different point of view than I was coming from, and I hadn't smoked any dope at that point, so I didn't get the hip references and stuff.

It's funny, though, because his early influence was Carl Barks. So in a sense, you were coming from the same original place, but just diverged on totally different paths by that point.

Yeah, but Crumb was a little bit older and a little more mature, and he was just doing a different thing from me. So much of it was still about artwork, and it wasn't until Zap #2 and #3 came out and they've got Rick Griffin doing stuff, and all of a sudden I get it. I really liked this guy, Rick Griffin. And in fact, the first two issues of Promethean Enterprises that we did in ‘69 and ‘70, both have Rick Griffin covers. So for me, early on, it was more about the art than about the stories. I mean, I loved comics, Marvel comics for the stories, but for underground comics, I was really looking more for art.

How had you gotten into your own fanzine publishing with Promethean and Anomaly?

Well, somehow the three of us, Al Davoren, and Jim Vadeboncoeur, and myself came together and said, let's do a fanzine. Jim and I had more interest and roots in the more conventional comic scene as far as Al Williamson, and Frank Frazetta, and all that. And then Al was more into the underground scene, which we were all very aware of. But Al was the guy who would get Crumb to do us a cover. Crumb is going to barely going to talk to me; I'm just some punk little kid.

But the three of us got together, and I don't know why we suddenly said we wanted to do a fanzine, because everybody and their brother was doing fanzines then. That was just a way of getting a creative bent going and sharing with your friends. That was in the sixties, it was all about doing fanzines and selling them to people for 50 cents or 75 cents or a dollar.

But you actually had what I think is the first published interview with Robert Crumb, right?

That is correct. That is the story, which is hard to believe. I mean, even fucking Rolling Stone should have come along and done an interview with him by 1974, but they hadn't. So yeah, Al did the first interview we had that was in Promethean #5.

Did that seem significant to you at the time, or is it only in retrospect that you realized that's actually a part of cultural history?

Only in retrospect. At that point, we were just in the middle of living it, so we didn't know where things were going. I had no idea the undergrounds were going to peter out by the late seventies, but it was obvious that they were a creative place to do stuff, and they were a really good entry level for new artists to do material. All you needed was enough money to print 10,000 or 20,000 copies, and there was this funky little distribution system set up between Last Gasp and Rip Off Press to distribute this stuff. And guys like me, I was taking undergrounds to conventions starting in 1969, 1970, and people were asking, “Whoa, what the hell are these things?” Undergrounds were not penetrating deeply into Houston and Dallas, or even into New York City.

At what point did you decide to start doing the convention rounds all across the country?

I really wanted to go to Houston in ‘68, but my parents wouldn't let me. I guess I had just turned 16, and they told me that they were not going to let me drive to Texas with a couple other teenagers. In ‘68, there was the Berkeley World Science Fiction Convention, and we all went up to the Claremont Hotel, and we shared a table, and all of a sudden we had our dealership. We always had this little dealer mentality. We were just a bunch of little hustlers. We were not going to just go to the show and run around. We were going to have a table with some comics on it and try to make some money and go buy some more stuff. So that was actually the first [convention we sold at]. That was four of us that were part of Seven Sons.

Wait, were we in Seven Sons by then? I'm not sure. But anyway, the Berkeley World Science Fiction Convention was the first, and then a year later, I got to go to Houston. The four of us again drove down to Houston and did our first show, and met people that I still see every year. And then in 1970, we went to New York. Michelle Nolan was a little bit older, and she had driven to New York, I think in ‘67, ‘68, ‘69. She had gotten to know Phil Sueling because how many people were driving 3,000 miles across the country to go to a comic book show?

Michelle was staying in Phil's apartment, and eating his breakfast cereal, and driving around, because Phil didn't have a car. He was a hardcore Brooklyn kid, and he didn't need a car in a city like New York. Phil finally did get a license, and he was a really terrible driver, but back in those days, he didn't have a vehicle. Michelle would be providing the vehicle. And then once we started going back, all of a sudden we were roped into staying with Phil at his house — at his apartment, I should say — with his two kids and his wife, and we were roped into driving stuff from Brooklyn into Manhattan for the show.

How much were you making, profit-wise, at those conventions versus what you were selling through your shops?

The early shops didn't make squat. I mean, we were able to pay the rent, but we weren't making hardly anything. I remember something like making $27 on a Saturday. I mean, it was peanuts. I'm sure things were up and down from that, but in those very early days,we hardly made anything. But the rent's seventy-five bucks, so how much do you really need to make?

Once we opened the Berkeley store, we had to get more serious about it. I don't know what we were paying in Berkeley, but it might've been a substantial amount. It might've been $600 or $800 a month rent. It was a big store. It was bigger than we could even fill initially, so we had to get more serious about it.

You were selling a pretty diverse set of items: you had comics, you had fanzines, you had art portfolios. Were you dealing in any original art at that point?

Just a tiny bit, but that didn't really start until we met Phil Seuling in 1970. I remember we came back to California with a bunch of Our Army at War and GI Combat DC war pages that Phil had sold to us for five bucks a page — this would be Joe Kubert and Russ Heath's stuff — and we brought them back and sold them for, like, $10 a page. We were barely on the edge of that stuff. I mean, I distinctly was not interested in original art in the very early days. I said I'd rather spend money on comics.

That market really must have been just developing right under your nose as you were getting into it.

Absolutely. And money was really tight. When we went to Oklahoma City, when John and I were working together, we grossed $450, that's it. And we went to New York with basically the stuff we didn't sell in Oklahoma. In New York we made, I believe it was $750, and we were freaking elated. And you're talking about driving all the way to the East coast to make $1,300.00

You're spending all your money just to get there and back.

Oh, yeah. And gas was 30 cents a gallon. We came back, we owed Phil Sueuling 500 bucks. That's one of the stories I always like to tell, because Seuling doesn't know us from Jack, but he puts us up in his apartment. He uses us to help security at a show, and he sends us off, owing him 500 bucks. It's like, what kind of a person is this?

And what was the answer to that question?

He's a fellow comic book enthusiast. He knows we're huge fans. The only guys that are driving in from California because we couldn't afford to fly. I was still only, what, 17 or 18? I was still in high school. I'm not flying to the East Coast. But Phil was a high school teacher, so maybe to put it in good light, he was a good judge of character. Maybe he thought, yeah, these guys are all right. I can trust them.

We were partners. We partnered up buying a lot of fanzines and stuff together, and every time we'd get together, which might be once or twice a year, we would do a whole bunch of accounting and figure out who owed what to who, because we'd be buying stuff and sending things to him, and he'd be buying stuff and sending things to me. This was really early. This was even before the direct market when we were just talking about splitting print runs on fanzines.

So that was really the beginning of your business relationship with Phil which would evolve into those first steps in the direct market.

Right, right. But the direct market was definitely all his idea. I mean, I wasn't in New York. I wasn't old enough to be going and talking to Marvel and DC.

That was 1973, when Phil made his approach to Marvel, DC and Archie, and then came to you. How was this all presented to you?

Most of it is memories of memories now, which is not really clear, but basically my understanding is the same one you see in print all the time. He just went to the companies and said, “I'll buy your comics for 60% off, no returns.” Which was unheard of, because they were used to selling to distributors and getting affidavit returns, which meant they print 100,000 and they only sell 50,000. The rest of them either go out the back door or get pulped. And here Phil was giving them real money for stuff. Comics companies were not doing that well in the first place at that point. That was not a great time. Phil had a good idea, and he was mature enough and a good enough salesman to pull it off. He was still teaching in high school, but he had opened a shop. He was an entrepreneur and a smart guy. I mean, New Yorkers in general, they're aggressive.

We were naive little California boys going back east, and even the girls were more aggressive and grew up a lot faster in New York than they did in California. I started buying the comics from Phil. We were also buying comics from the local distributor. We would supplement them both. If we ran out of something from Phil, we'd run over to the distributor and try to get some copies. But that was strictly for the stores. I was not messing with regular comic books, newsstand comic books, in my mail order business. It was all strictly the other stuff, everything but comic books, basically.

My mail order was strictly new material, but underground comics, fanzines, and any books that I could find about comics and comic strips — which were very, very few at that point, only a couple publishers. Nostalgia Press was one, and Chelsea House was another. They had done the Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon reprints, the early ones. I was carrying that stuff. I'd come back to New York and go to their offices and pick up a box of this and a box of that and haul them back to California. But that was it.

The Underground comics were a big thing for me. I sold lots and lots of 50 and 75 cent underground comics through the mail. The fanzines were a little slim, and I couldn't carry really junk fanzines. They had to be decent ones. I was carrying Voice of Comicdom, and Squadron, and Graphic Story Magazine, and the better of the comics fan ines that were coming out from 1970s on.

Speaking of Graphic Story Magazine, you had gotten in touch with that group down in LA that [publishers and fanzine editors] Bill Spicer and Richard Kyle belonged to, right?

Graphic Story Magazine was at the very top. That was the top tier fans. I got to know those guys through dealing their fanzines, although I wasn't really part of the LA group, per se.

Were they influencing your own thinking about comics? Because they had their whole theory of comics and aesthetics, and it really informed the stuff that they were putting in Graphic Story Magazine.

They were hugely influential in sort of legitimizing comics, just like Gary [Groth] and the Comics Journal were approaching comics from a critical standpoint and dismissing some of the lesser bullshit stuff and saying, “Now this here is good storytelling.” Alex Toth is good storytelling, and Basil Wolverton and Al Williamson, and of course Frank Frazetta and stuff. They [Spicer and Kyle] were drawing everybody's attention to the better material. That's why those issues were so good — somebody was actually collecting some of that stuff, maybe interviewing the artists and putting that out there.

What was the impetus for you putting out things like The First Kingdom?

That was really the beginning of the independent comics. When we first picked up The First Kingdom, we didn’t think that we were breaking any real incredible new ground. Jack wanted to tell this long-term story, and it sounded like a cool idea, but there were a lot of underground comics coming out and morphing into independent comics, like [Mike Friedrich’s] Star*Reach and that sort of thing. So the First Kingdom was just another comic in that genre. I guess I would say the difficulty with the First Kingdom is that it only came out every six months, and that was a huge limitation, I think, to its success. The first one went through four printings, which is hard to believe.

By the time we got up to issues #15, 16, 17, I was not selling 10,000 copies anymore, or 20,000 copies. I'm not sure if I was still printing 20,000 at that point. The standard print run on undergrounds at that point in the early days was usually about 20,000 copies. Just as an aside, we would gang print stuff with Last Gasp. So basically I'd go to Last Gasp and say, “Okay, you guys are going to be printing four comic book covers at the same time. I want to be one of those covers, so I'm going to put The First Kingdom in there.” Same thing with Anomaly. We're going to do Anomaly, but we weren't doing it as a separate printing job. I'd go to Last Gasp, and Last Gasp would contract with their web printer and do the guts and do the covers, chop the covers up, and I'd have 20,000 copies of First Kingdom,.

Which must have made it difficult in the mid-70s when the bottom fell out from under the underground comics.

Eventually, the First Kingdom was the only thing I was doing. I've never been that successful as a publisher other than publishing catalogs. I'm really good at catalogs. But by the time I got to the end of The First Kingdom, did I really make any money? Maybe not. I had to pull a shitload of copies that just weren't selling. When Barbarian Killer Funnies [another comic published by Plant in 1974] was done, the guy took so long to get it done that the market had started to go bad. I think I paid him more than I should have as far as royalties, which shows what a bad publisher I was. And then of course, Phil Seuling and I did the Spirit Coloring Book, which was another disaster. I mean, it was a wonderful book. And we worked with Will Eisner, and that was really great. But a coloring book? Nobody wanted a coloring book. That was 1974, right?

You were before your time.

Yeah, we took us a long time to sell those. And same thing on even Promethean. I was selling that thing for the next literally 20 years.

Before the market really started to feel the pinch in the seventies, right before the dropoff of the underground movement, you have Berkeley Con in 1974. Tell me about how that came about.

That was started by two guys, Nick Marcus and Mike Manyak. And they eventually opened a store, but at the time, they were just a couple of comic book fans. I'm not sure if they really had the underground orientation. I think they just wanted to put on a show show in Berkeley. They came to us at Comics and Comix. We were the leading store at that point and they said, “We want to do this show, but we're not exactly sure how to do it. Do you guys want to work with us?” And we said, “Shit, yeah, of course. Have a show in our hometown instead of going to Texas or New York to do them.”

I think that we may have oriented the show. I don't know. I could be wrong. So this is speculation, but I think we may have ended up orienting the show more towards the underground area because we were selling so many undergrounds already, and all those guys were there.

It's just the local scene.

They could all come to the show. You're an underground artist? Come to the show, you get in free. You can be part of the art show, you can sign your comics, whatever you want to do. It was all really loosey goosey stuff. That's where, famously, the San Francisco Pedigree Collection walked in the door, and Nick and Mike were the first to get their hands on that and got a bunch of the Timely [books], and we ended up getting the rest of it. That helped us. We used to claim that we financed a couple new stores opening because of that San Francisco Collection that walked in the door. But that whole show is, for me, a total blur, because I was one of the guys trying to run the show and trying to man the door, and we had to build the art show because we couldn't put anything on the walls. We put it on at the Pauley Ballroom off the [UC Berkeley] campus because they weren't going to let us nail art to the wall. We had to go buy plywood and two-by-fours, and build four walls that were going to sit within an area, and put the art show up there. And man, I remember building the art show but I don't remember what the hell was in the art show at all. I mean, gone. It was just a blur of activity for whatever it was, two or three days.

Was there a sense at that point that it was sort of the last moments of the golden age for the Berkeley scene?

No. No, not at all. I don't think we ever sat back and got a real perspective on things. There were certainly people that would do that, guys like Kyle and Bill Spicer. But I'll tell you, we were just doing the next designated thing. I was still in college at that point, going to San Jose State until ‘75, and it was just a blur of activity. We were doing what seemed to make the most sense at the time. I was still majoring in business and marketing, but I was thinking I was going to get a real job at some point. I didn't know that things were going to turn into a career. But it did make some sense to go and get some business education anyway, since I was kind of in business.

So by then, it was starting to dawn on you that this just might be what you do for a living.

That is true. It seemed to be working that way.

Meanwhile, by the mid seventies, you were in the nadir of the comics industry in general, both for the undergrounds and for the Marvel and DC stuff. You must've been feeling the pinch, right?

No, I actually don't think so. There was a pinch in ‘78. That was my big memory — the gas crisis in ‘78. I was wholesaling by then with the fanzines and stuff, and I was getting people that weren't paying me their bills and money was getting tight. So things must have slowed down. I'm not aware of the numbers per se, but I remember in ‘78, I was getting divorced from my first wife. We had been together for three years.

But yeah, I was questioning what I was going to keep doing in ‘78. I was running out of money. It was getting really tight business-wise, so obviously things were not doing real well. I probably was making no money at all out of Comics and Comix; I never really made very much out of it anyway. I was not really working the counter and putting in time there. I was just basically providing material to them, and they were paying me for it at my cost, generally.

But things got really tight. I was trying to get a loan from the bank and getting nowhere on that because I was still too young. I didn't have any real credit experience. I finally had to borrow some money from my parents to get me through at that time. I was really questioning what I was going to be doing. I had my first major vacation after I had gotten divorced. I went off with a backpack and went to Europe for about five weeks, wondering if it was time for a career change or something. But actually, I came back with renewed energy, and the Seuling Con was coming up very shortly after that. I came back and borrowed the money from my parents, got the business back on track and things started looking up again. Basically the rest is history.

By then, as you get into the late seventies, early eighties, Phil Seuling’s monopoly on the direct market gets broken, and you have this preponderance of different regional distributors. You have Pacific down in San Diego, you have smaller regional guys like Destiny to whom you were sub-distributing. Did that make things easier or harder for the business you were running?

Oh, I think it made everything easier, basically. At that point, the business was expanding exponentially. I loved Phil, and he did a great thing with starting the direct market, but he was holding it down. He was a clamp on the direct market, a bottleneck, and breaking that open and getting other people distributing comics was the best thing that could happen. The market really exploded at that point. Everything was doing really well. Stores were doing well. I was doing well with my mail-order business, and that's what got me into carrying new comics. That was in, what, 1982. And you probably read that story where Charles Abar’s wife told him, “You can't have these two, three jobs that you're doing. You got to do something else.” Charles was an early comics distributor, and he is still a distributor of supplies. He's a guy with real incredible integrity. It didn't really matter what he got out of the business; he just wanted to take care of his customers.

He said, “I think Bud will take care of my customers.” John Barrett, my partner in Comics and Comix, had been after me for years to become a distributor. Of course, it meant better discounts for Comics and Comix. John was always looking at the bottom line. That's what got me into comics distribution from ‘82 to ‘88.

Scrimping and saving aside, somehow you were the one in the right place at the right time with enough capital to start scooping up these guys when the glut in distribution and publishing made a number of them drop out of business by the mid-eighties.

I really wasn't scooping them up. That's more Diamond. I inadvertently … Pacific went bankrupt on me, so I had no choice. I always say that that's the best thing that could have happened to me. Pacific owed me $25,000, and Bill Schanes tells me that they can’t pay me, but they will give me the business. And they tell me who the guy is who I should have running the warehouse in L.A. All of a sudden, I'm the distributor for LA and Southern California — which nobody knew what that was worth, including me, but it was certainly a cheap acquisition and a huge growth in my business. It gave me more buying power and more ins with Marvel and DC. Because even at that point, DC didn't want to deal with all the distributors. They were limiting their distributors to whatever the number was, maybe six or something. That's why there was all this sub-distributor thing going on. Pacific owed me all that money because I was carrying DC for Pacific. I was sub-distributing DC. Evidently DC liked me. They thought the Schanes were just kids and they didn't want to set up an account. They were happy to have a limited number of accounts and not just set up anybody that came along. I was selling DC to [Pacific] and to Destiny.

I guess that was the business model of [sales manager] Mike Flynn at DC versus Carol Kalish over at Marvel.

Yeah. Marvel was more open, though. Marvel was pretty much willing to deal with just about anybody. DC was still the old school guys that wanted to be in bed with a limited number of people and figured, “That's enough. We don't want to open this thing up to everybody.” It was a growing market and you got all these distributors out there hustling comic book stores. There were shitloads of warehouses, and any comic book store in a major city could buy stuff right off the racks in a warehouse. The system was growth oriented, and the comics were popular enough, getting enough publicity by then, that people kept walking into comic book shops and buying stuff. Newsstand distribution was probably going to hell at that point, too, so the only place you could get your comics was comic book shops.

Why did you cash out? In 1988, you sold your distribution to Steve Geppi, and you sold the shop. Why then?

I was in deep financial shit. I was really in trouble. But I was insisting on a model that wasn't the healthiest in the world. I was trying to give credit to comic book shops. I had gotten educated by the real book world and real bookstores, and so I was promoting carrying back stock and keeping graphic novels and books in stock in the store. At the time, a lot of stores were still acting just like Diamond was acting. They had the periodicals flow through the store and move on to the next thing next month. And I was advocating being more like a real bookstore. A family could walk in and they could find an Elfquest book or Calvin and Hobbes or whatever was out there at the time. I wanted to have a more full-fledged, diversified store.

So I went with the model in the book industry of giving people net 30 days [i.e. 30 days to pay for goods after receiving an invoice] and letting things grow. That's where Phil Seuling and I differed, because Phil was smart enough to know that there were a lot of amateur operators out there. And giving them credit is probably a recipe for disaster. I got myself into trouble. I mean, I was growing, but at the same time, my accounts receivable was growing exponentially. Comics and Comix was making the same mistake as a lot of other stores. They were overstocking too much stuff and they didn't have tight enough inventory control. They were tying too much money up and they started stretching out what they owed me from net 30 days to net 60 days to net 90 days. They were chewing up my operating capital, and then Chuck Rozanski [of Mile High Comics] went bankrupt at that point. Alternate Realities, his distribution company, was just like Pacific had been in 1984. At this time, Chuck and Alternate Realities owes me $180,000. That's big, big money. And Comics and Comix owed me over $200,000.

God, I was getting into deep, deep shit and looking at the possibility of going out of business, and I had these guys pushing me out because they owed me so much money. When the opportunity came along to sell to Diamond, I have said that I was hanging on by my fingernails. It made all the sense in the world for me to get the hell out of trying to distribute new comics and go back to what I was, I think, better at, which was selling books and fanzines and stuff related to comics. So that's how the deal came about.

The kind of grim irony here is that what you were trying to do was basically the future of comics, this focus on a consistently stocked backlist of titles rather than new books over the direct market. Were you just too far ahead of it?

I didn't have enough financial control over it. I actually had a financial controller, but he wasn't as good as he could have been. We needed to have clamped down tighter on people than we did. I wrote off about $150,000 worth of bad debt when I sold out to Diamond because Diamond didn't take my accounts payables. I had guys like Gary Arlington of San Francisco Comic Book Company. He is a fucking icon of the business and he owes me $10,000 bucks. And I can't get it out of him. I can't. Bob Sidebottom at the Comic Collector Shop, he owed me $7,000 bucks. And finally I said, “Bob, I got to put you on COD. I can't keep giving you credit. You're running up too much credit.” He says to me, “Why didn't you do that earlier?” Well, because he was my friend. I've known him since I was in high school. I didn't want to insult him. I'm used to handshake deals because that's the way everything was back then. So yeah, I'd gotten myself into trouble and I paid the price for it.

So then it was full circle back to the mail-order business.

It was back to the mail-order business, which had become literally 3% of my business at that point. When I sold out to Geppi, I was grossing, I think about $12 million-$12.5 million a year. What’s4% of that, about $350,000? So that's about what I was doing in the retail business. I had neglected it. I was busy dealing with multiple warehouses and all my managers and distribution and stuff. We just spun back off the little tiny retail business. When I made the deal with Geppi, he literally took over my warehouse location, which is the same damn location I'm in now.

And they ran the warehouse. I worked for him for about four or five months just trying to make things work. They eventually moved out of the place and I moved back into it and with my six employees, and then rebuilt the whole thing. Actually, my most lucrative years were probably after that, in the 1990s and the early 2000s. That's when my business was really, really doing well. Everything I didn't have to discount was selling for full price, and I was the one-stop shop for a lot of different material. We kept growing and growing during that time.

Did it come as a relief to you? Did you like doing it compared to the many different businesses that you had been in up to that point?

Yeah. I liked being a hands-on bookseller, getting stuff that I really enjoyed, and having it available for customers. That was what I started it out doing in 1970. I went back to my roots, basically, which is what I still enjoy the most, making a deal. Discovering some guy that's done a good book and bringing it in and then telling people why they should buy it. It's a pretty simple model. Putting out a nice catalog so people can see what things look like. I'm kind of small potatoes in that way. I didn't have grandiose visions of taking over the world like Geppi did, and I wasn't having a good time having seven warehouses and having Comics and Comix owe me all kinds of money. My fate was in other people's hands. So taking that back, and having it all under one roof, and having me in control of what I'm handling, and nobody owes me money anymore — I like that. Now I'm a retailer and they give me money. I don't have any accounts receivable. That's the danger zone for businesses.

What was the transition to the internet like for you?

We were an early innovator, but we didn't know how successful it was really going to be. The first transition would've been to basic computer stuff. We were getting into computers when I sold out to Diamond. I wanted to computerize all the warehouses. I had the right idea, but at that point, computers were still very expensive and had removable discs. We paid $1200 for a removable disc, and now you've got a desktop computer that you pay a thousand bucks for, and it has more memory than our removable disc. I had a devoted IT person just running the thing.

But to answer your question about the Internet in the early days, we adopted it as fast as we could and got a website going, but we didn't realize how important it was going to be. I had a marketing director at that point that just didn't really see as much value in it. We were sending out emails to people. This is really early, but we weren't really exploiting it then. We’d do this massive mailing of new items and other stuff every week, and we've been doing it for years. We have a catalog that's completely uploadable that people can run through and link to stuff on our website. We’ve got it all down now, but back in those days, we were still depending really heavily on the print catalog. The early Internet was still sort of an adjunct that it was doing okay, we’d get some orders, but it took a while to just get off the ground.

Do you remember when that threshold was crossed where most of the sales were coming in online versus in print?

Off the top of my head, no. The strange thing is that I am kind of old school, because here I am still doing a print catalog, and there's a question of whether it’s really still paying off anymore. Is the cost of doing a catalog going to keep going up? It's hard to say. Things started going downhill in general in 2008, when the huge economic crunch hit. I saw my sales start to drop. And basically I had a period from 2008 to 2011 where the business wasn't making any money at all. It was basically losing money every year.

That's when I had a marketing manager who probably wasn't exploiting the internet nearly as well as he could have. We were more dependent upon catalogs, and we were trying to compete against Amazon and online sellers. We'd been trying to grow and do more general art books. That's when we changed the name to Bud's Art Books. We were trying to break out of the comic book market, which was really a huge mistake, because of my marketing guy. I'm going to throw him under the bus: he lost sight of what the niche market was that I'd been serving for all those years and that I knew so well. And all of a sudden we're trying to sell more general art books and stuff because we were able to reach those guys. We were renting huge mailing lists and doing very well, sending them catalogs. But basically, we couldn't compete with something like Amazon, and we lost our way there. And that's why at that point in 2011, I was going to just close the business down and sell out, and we downsized because we really had lost touch with what made the business work. But I couldn't let go. I rebuilt the business by doing the same thing I'd always been doing, which was selling the kind of stuff that I like to fellow fans and collectors.

What made you change your mind and stay in business?

That's a good question. I think part of it might've been ego. The business has always been me. That's where my identity is. I've always been the guy selling this stuff for 50 years, and it was a hard thing to let go of. It was hard to give up and say, I can't do this. I was looking at what had been happening with my bigger staff in 2011. We had a staff of 11 people, had a manager and a marketing guy and all that. And I hadn't liked the direction they were going, and they hadn't liked the direction I was going. They were unhappy with me and what I was trying to do. And so, we parted ways and as we were trying to wind down the business, I was also thinking that I’ve still got business out there. I’ve still got customers that want to get stuff from us. For a while, we were trying to sell the stuff we had in the warehouse, and then we decided to start again. Get some more of this new stuff in here and let's make it work again. We brought back LaDonna Padgett, who had been an employee of mine for 40 years. She is really invaluable.

So that takes us up to the present day. Tell me about what's going on now.

It's really not so much financial difficulties. I mean, the business has been doing okay. Covid was actually kind of good for us because a lot of people, as you know, were sitting at home and our business went up and things did really well. But since Covid, I've seen our total sales drop off at the same time that our expenses just keep going up and up. The business has been making a little bit of money, but not a whole lot. But that's really not my motivation for retiring, although it’s one key to it.

The fact is that I've been basically running the business for about the last two years and not making any salary at all. I get a few perks, but it's not throwing off a salary for me. I'm living on Social Security, and I've also got all these other side gigs going. Anne [Hutchison] and I have an antiquarian book business going, and I've been selling people's collections of comics and prints. I've got plenty going on. Money's not really an important thing in that respect, except for allowing me to buy more old comics. I've been running the business almost for my employees, and also because of just inertia after 55 years. It's easier to just keep going. I'm only working three days a week now, although the business never goes away. Sunday afternoons, I'm answering my emails. Anne and I have been thinking for a long time about basically slowing down just a little bit. And it definitely seems like the time; I've got a couple of employees that have said they're going to retire when I do, and everybody knows what's going on. I want to basically just slow down a little bit, and not have to be going into a warehouse, and not have to deal with employee issues, and rent, and ever-growing bills for software stuff and upgrades, and stuff like that. So this is the time. I don't really want to be doing this when I'm 80 years old. I'm happy to be selling old books and old comics, but I don't really need to be making a payroll every two weeks.

Do you ever worry in the back of your head that you're going to regret getting out of this?

Yeah, a little bit. When special stuff comes along. I guess an example would be stuff like the EC Fan-Addict that was being published by Roger Hill, who passed away not too long ago. I love handling stuff like that, and that's what I'm going to miss, because I don't know how to incorporate that into what I want to do now. But there's a lot of stuff that I bring in and that people just don't respond to — a lot of graphic novels that sound good to me, but my customers are kind of old school and they're not as excited.

It's getting harder to predict what's really going to be successful. I really like French graphic novels. There's a lot of really wonderful stuff coming out in France that's being translated right now into English, and they're really fun, and they sell okay. Some of them bomb, some of them do okay, but it's hard to know what's really going to sell and what isn't. And to really be successful, I need to be growing again. I need to be out listing my stuff out there on eBay or on Amazon. Right now I just have a website and a print catalog. And so my customer base is actually shrinking, and that's not healthy, but I don't have the staff to do that expansion.

That's why that dovetails right into why I'm trying to sell the business. Somebody could come along and do that — that's what you need to do. If I have a book that's not successful with my base customers, it could be successful out there on the net because I've got it in stock and I'm going to pack it really carefully, and you can call up and talk to us about it. We provide this service that you don't get from Amazon or on eBay, but I'm at the point now where I don't want to take the time and energy to do that, and neither do my employees. Nobody wants to deal on eBay, but that's a good place to get rid of stuff. I'm holding the business down. I'm bottlenecking it because of my age and my old-school attitude. I think that's the difficulty. That's why business is going down rather than going up.

When you look back on everything you've done, what's the fondest memory, the best memory you have of your whole time in the business?

Well, I'd say a couple things. One would be the prime years of San Diego ComicCon, when we used to have 10 booths down there. Up until 2008, we had grown to the point of having 10 booths. It was an incredible expansion on what I was doing in 1969 and 1970, but instead of having a table of undergrounds and fanzines, I'm going to San Diego with a semi and with 10 employees. We've got the grooviest friggin’ books in existence that a lot of people haven't seen, and we build a whole trade show setup to display that stuff and to sell it in quantity. People could come in and they'd find stuff they wouldn't find anywhere else, and they'd get excited about it. All the artists would come by. And we used to do signings with people. We did signings with Jack Kirby and Burne Hogarth, and just fun stuff. It was a hell of a lot of work. But that was a high point of actually being out there with the public.

I like to write a description and do a catalog and get it out to people. I don't really want to be on the counter of a store and having to get into long conversations with people. But in San Diego, it was really fun. We were the big man on campus in San Diego up until that point. And then Marvel and DC and the other companies started eclipsing us. And then the people coming to San Diego, they didn't come to buy heavy art books that they'd have to lug around. They came to buy specials that are only available at the show and stuff.

So we sort of lost that market. The one other thing I'd probably say is putting together the catalogs. I'm the guy that chooses the cover of every catalog, and we go out to the artist and talk to them and make sure everything's copacetic. And sometimes a couple of times the artists have done things for us, and generally people are real pretty happy to get us on the cover of the catalog. Maybe less so now, but it used to be kind of a prestigious thing to get on the cover of my catalog. I really like being able to pick out what I think is the best item that we're carrying for that period of time and put it on the cover of the catalog. It's sort of a creative aspect. It's kind of like doing a fanzine, right?

I know it's going to be a little tough. It's going to be tough for me to pull away and tough on some customers, but hopefully, they'll carry on. There'll be other ways. It's just like Diamond going under. There's going to be other ways of getting your comics and a distribution system. I'm going out with my head high, and I'm not going to stiff anybody.

You know, maybe that was a bad analogy.

The post Bud Plant is calling it a day: A conversation with the comics retail pioneer appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment