Not gay as in happy, but queer as in fuck you.

- Ancient proverb

There are many kinds of power, used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise. The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling.

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”

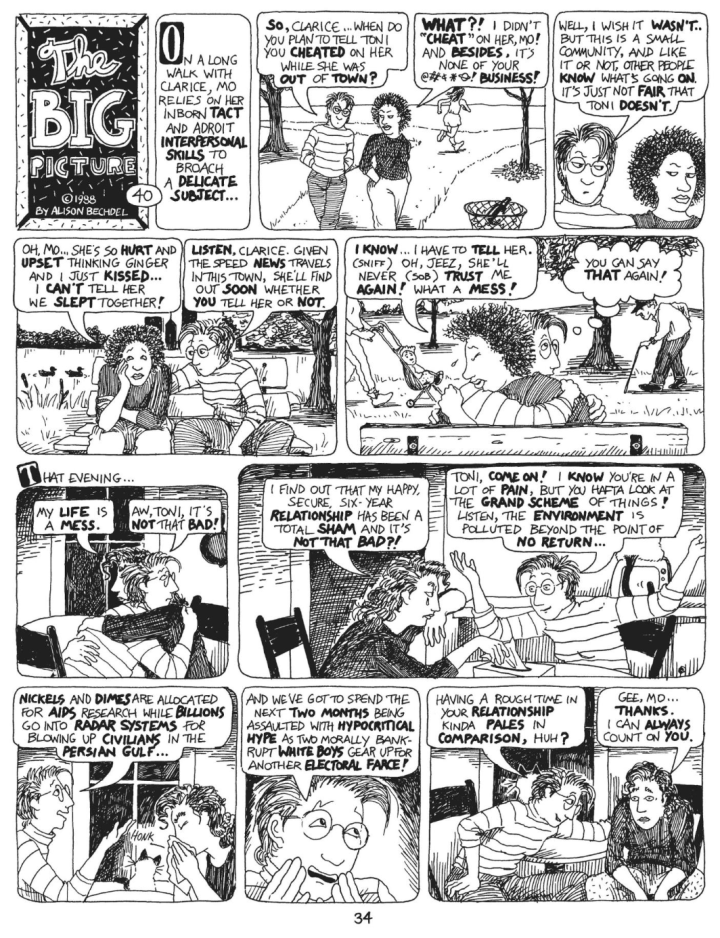

It’s four in the morning during my vacation. I’m in a comfortable bed and should be at my most relaxed, but instead I’m lying in an anxious fugue state speaking to a highly animated lesbian in a striped shirt. She is gesticulating wildly and shouting at me about political catastrophe. This goes on for a while until I finally stumble out of bed at five a.m. in search of coffee. With a warm mug in hand I sit down and open my current reading material, Alison Bechdel’s The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For (DTWOF), a massive tome collecting decades worth of her hilarious alternative newspaper strip on lesbian culture from 1983 to 2008.

If you’ve read DTWOF, you likely recognized my early morning visitor as Mo, the series’s neurotic, protagonist. While a dream intrusion may not sound like the most glowing endorsement of Bechdel’s strip, I would recommend DTWOF to just about anyone. Its storylines are hilarious, and the long, serialized narratives develop its characters into emotionally complex, subjective individuals. While I read DTWOF in three long sessions, I would strongly recommend reading it in smaller chunks, as the strip was initially paced in it's weekly run. If you’re anything like me, the constant political anxiety of the comic is sure to get to you, and while the strip’s Clinton and Bush era concerns can feel a bit quaint now, the anxiety remains all too real.

So it was with trepidatious excitement that I began reading Bechdel’s newest book Spent: A Comic Novel. Spent is a memoir, or a novel, or a work of fanfiction, by way of self-insertion from the source material’s author. In it, we catch up with the central characters of DTWOF a couple decades later, living in the on-the-nose lesbian setting of small-town Vermont. Instead of Mo (who bears a striking resemblance to Bechdel) and her partner Sydney, Spent’s central characters are Bechdel and her real life partner, Spent’s colorist Holly Rae Taylor.

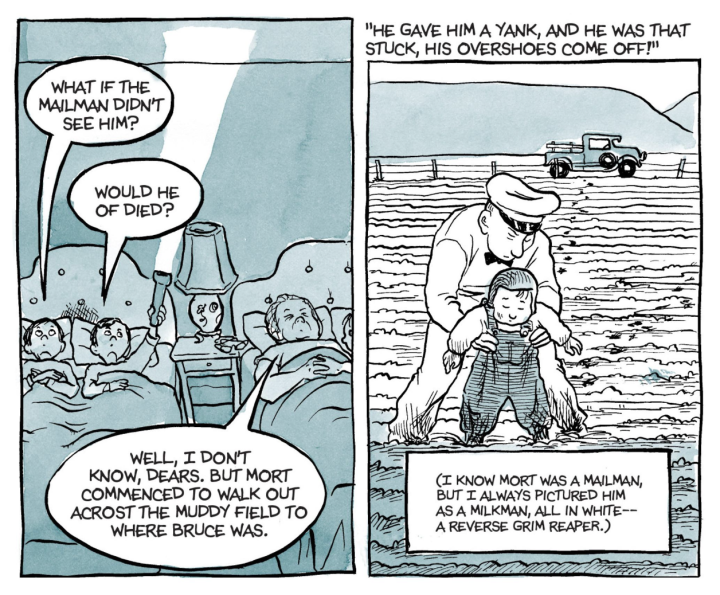

The mix of memoir and novel, fact and fiction, has long been a part of some of comics history’s greatest entries, from Justin Green’s Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, to Robert and Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s Drawn Together, and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Something about the unique convergence of image and text in comics allows for a magical blending of the two seemingly opposed worlds. Bechdel’s, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, toys with this idea in a famous scene in which a character is drawn as a milkman even while the caption above the drawing notes “(I know Mort was a mailman, but I always pictured him as a milkman, all in white—a reverse grim reaper.).”

Bechdel’s work is intensely intertextual, often allowing other works to interpret her story as much as she interprets them. Fun Home uses constant literary references to classics like Rememberance of Things Past, The Great Gatsby, and Ulysses, among others, to structurally make sense of the unanswerable questions surrounding her father’s death and sexuality.

Comic book expert, Hillary Chute notes of Bechdel’s obsessive fealty to archival accuracy, “Fun Home recuperates an archive of family documents…in order to seek out the specificities of a man who felt abstract to his daughter, and also to propose the embodiment of the cartoonist’s link to the past (and hence to her father)."1 Bechdel painstakingly copied family photos, handwritten documents, and wallpaper in Fun Home, and DTWOF constantly references real world political events on TV and newspapers. For Fun Home, the archive is an object not only to prove the veracity of its narrative to the reader, but also to make Bechdel’s connection to the past tangible for the author herself. Although remaining referential, Spent shares neither Fun Home’s reverence for its intertextual interlocutors, nor DTWOF’s anxiously realistic obsession with them. Instead, Spent engages with Bechdel’s own bibliography, presenting an ironic view into the artist’s self-image. In the alternate universe of Spent, Bechdel hasn’t written Fun Home: instead, her magnum opus is a memoir called Death & Taxidermy, in which we see her father's punishment for taboo and unprincipled behavior in the form of an arrest for making a display from endangered species, rather than his a re-interpretation of Bechdel’s real father’s arrest for an inappropriate gay relationship with one of his high school students and later death, likely by suicide.

If Fun Home and DTWOF are the product of drowning in the archives that surround her, Spent is about the space that grows between the artist and her creations. This may sound strange given that Spent literally places Bechdel in her own fictional world, effectively obliterating all distance, but the characters of DTWOF treat Bechdel with a kind of parental disappointment.

They see her as a sellout, wasting her platform as a writer. She has allowed the villainous company "Schmamazon" to adapt her memoir into a TV show, butchering her story into tacky fantasy schlock. In Spent’s first chapter, Sparrow ribs Alison, declaring Alison can fly them to visit an Oberlin women's and trans collective "in your private jet" before the narrator reveals “Alison had withstood her friends’ ribbing about her windfall from the show with good humor. But lately, her patience is starting to wear thin.”

Alison’s anxieties in Spent underscore the essentially difficult question of how much a queer writer’s narrative is ‘worth’ in the constant struggle for queer rights and survival. Surrounded by the constantly, interminably activist characters of DTWOF and their constant, passive aggressive judgment, Alison’s work as an artist begins to appear useless and absurd. Spent constantly pokes fun at Bechdel’s real-world work(along with Death and Taxidermy, DTWOF is renamed Lesbian PETA Members to Watch Out For). In interviews Bechdel has discussed her unwillingness to label herself an ‘activist,’ given that she doesn’t see her comics as activism, and hasn’t dedicated her life to civil disobedience as thoroughly as the DTWOF characters have.

Despite this, art is rarely, if ever, politically inactive. Bechdel noted in an interview on Fun Home “That interplay between the personal and the political is an enduring fixation of mine[.]”Talking with Alison Bechdel.” Houghton Mifflin press release, June 2006, pp. 7–9. This war-cry of second wave feminism almost perfectly captures Bechdel’s work. In making DTWOF, Bechdel illustrated, in striking realism, the daily lives of the lesbian community; the strip is funny, smart, emotionally raw, and strikingly human. It combats, in a very tangible way, the damage done by archival silencing of queer women.

By resurrecting the same characters for Spent, but replacing Mo with herself, Bechdel does what so few writers find themselves able to do, and interrogates herself and her work. Bechdel is no longer narrativizing her life, as she does in Fun Home, a practice which she is already questioning in Fun Home’s very pages. Instead, Bechdel’s life plays out as a narrative present. Without the captionic hindsight of a narrator reflecting on the past, we are made to live out Alison’s anxieties in real time.

Much like DTWOF, Spent finds the salve for these anxieties in community. Bechdel’s original concept for the book was far more formalist, a memoir constructed from each and every financial interaction of a year in Bechdel’s life, again making the personal political and blurring the lines between private and public. Bechdel doesn’t strictly adhere to this focal point, opting instead to make it one facet of a story spanning multiple points of view.

By broadening the book’s scope, Spent is able to offer a subalternative to the overbearing shadow of money on all of our lives: queer love. As with DTWOF, there is an ostensible main character, in this case Alison, but equal focus is given to her many friends. As Alison worries she’s sold her soul, falling deeper and deeper into financial anxiety, we’re constantly shown what a life centered on care, rather than capital, looks like.

The relationships of the DTWOF cast have matured greatly since the conclusion of the series, with each of them more motivated by love for their partners and friends than they were in the original strips. By paring down the cast to the cooperative housing members and juxtaposing them with the anxious, self-involved Alison, the strength of the bonds between characters shines. Unlike DTWOF, there’s no sense of existential threat to any of the characters’ romantic relationships. Spent becomes about how we allow our relationships to sweeten rather than sour over time.

Holly Rae Taylor’s bright color scheme aesthetically cements this thematic change. Bechdel’s work is typically understated when it comes to color; Fun Home is colored only in shades of blue-green watercolor washes over black line work, and Are You My Mother? Features fairly sparse reds on mostly black and white art. Taylor’s coloring is far less somber and more playful. It’s reminiscent of Raina Telgemeier’s work, a balance of thoughtful narrative set in a playfully colorful world.

Spent sees Bechdel poking fun at herself on the page, laughing about the absurdity of being a ‘famous cartoonist.’ The book is a warm reflection on a long career of cartooning and queer thought. There’s a lighthearted teasing of younger queer folks, but also a sense that Bechdel is passing the torch to those same gen-z queerdos. Two twenty year-old polyamorous asexual activists are recurring characters in the story, and their concerns and anxieties are not-so-subtle tonal echoes of those of DTWOF. Bechdel breaks this anxious gay cycle by presenting her pink-haired vicenarian with a thriving community of queer elders to rebel against, emulate, and be cared for.

If Bechdel’s prior work was about creating a queer archive through diligent research and constant insistence on queer narratives, Spent asks how we learn to live in a world where our archive exists and how we fight to keep it. It suggests a radical futurity of care and love apart from but not ignorant of the concerns of capital and phobia.

The post Spent: A Comic Novel appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment