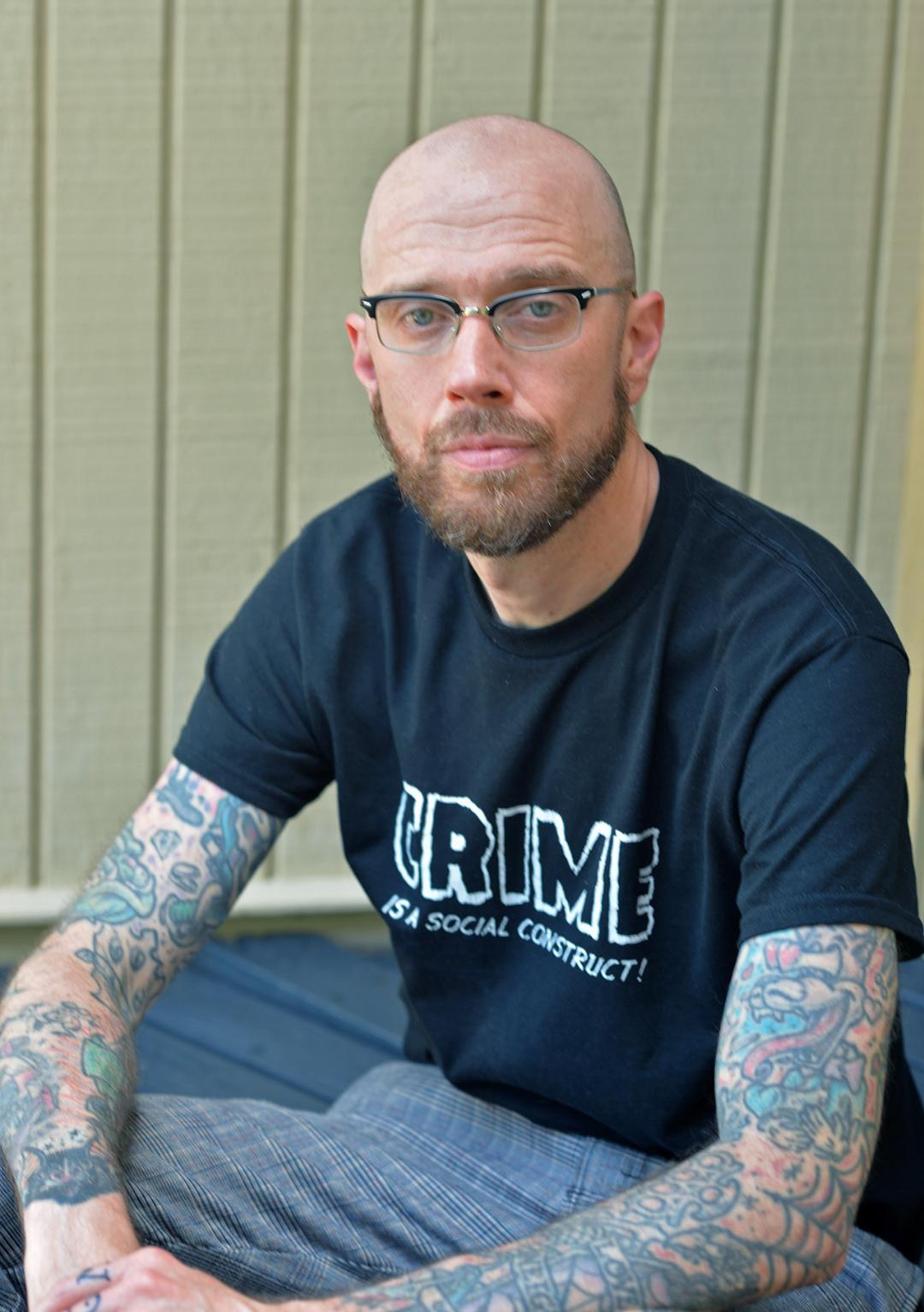

To survive under capitalism is to live amid dizzying disparities, both material and psychic. It is to know that a social need, however crucial, will go unmet if it can’t produce a profit for someone in a position to meet it and that notions of worthiness are inextricable from the reach of authority. Few artists capture this howling dissonance as well as Johnny Damm. Eschewing traditional storytelling conventions, Damm employs a collage technique that finds the imagery of genre comics placed against direct quotes from stakeholders on the subject at hand, often those who seek to wield their outsized influence to an advantageous result. In early works like The Science of Things Familiar (The Operating System, 2017) and Failure Biographies (The Operating System, 2021), Damm applied this process to poetry and criticism to create thought-provoking meditations upon art and history, which, in their juxtaposition, became greater than the sum of their parts. But in narrowing his focus to specific social issues and truncating these visual essays to comic book length, his work ascended to a new level of potency and vitality. In "I’m a Cop": Real-Life Horror Comics (2022), he places statements from the leaders of police unions in the United States against images from pre-code horror comics. RIOT COMICS: Tompkins Square Park, NYC, 1988 (2023) tackles the famed uprising in which unhoused people and advocates of squatters rights protested their eviction from the park. In Monster Crime (2024) he tackles the fear-mongering by retail executives who falsely attributed a post-pandemic crimewave to layoffs of retail workers and shuttering of stores, pairing their statements with images of leering monsters. The result of these juxtapositions yields a narrative of shocking clarity and a squeamish affect.

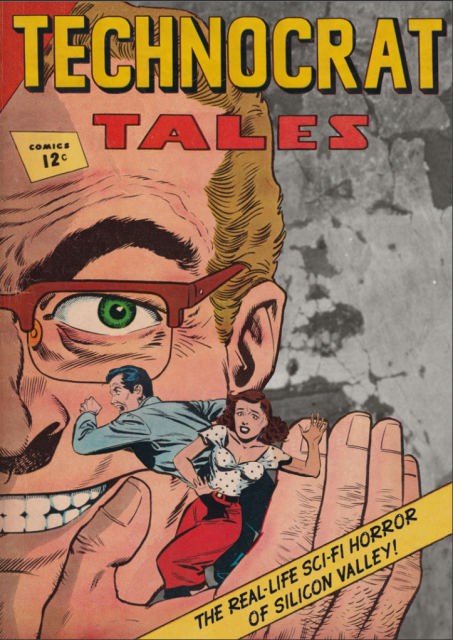

In his latest, Technocrat Tales, Damm trains his crosshairs further up the food chain, taking aim at the crushing force of Big Tech and the weird ideas that animate its leadership. Like a sobering slap in the face, Damm’s process of re-contextualizing embitters the words of our society’s most influential (and celebrated) leaders; words that are echoed uncritically in other arenas. Damm’s work is a potent reminder of how much we are conditioned to take as given and how much is taken from us as a result. He holds his ground with confidence in a tradition of comics that runs the gamut from Jess to Jack Kirby. I interviewed Damm by email in July of 2025. Descriptions in the images come from Damm’s citations in the work. — Ian Thomas

IAN THOMAS: What do you think readers should know about you to put your work into its intended context?

JOHNNY DAMM: For the last few years, I’ve been referring to my work as “real-life horror comics.” I make comics about subjects that I think people should be paying more attention to. Since 2020, I’ve been focusing on the horrors of U.S. policing, myths about crime and protest, and, most recently, the horrors of the big tech companies.

Can you offer an overview of your perspective and process and maybe point to the thinkers that informed it?

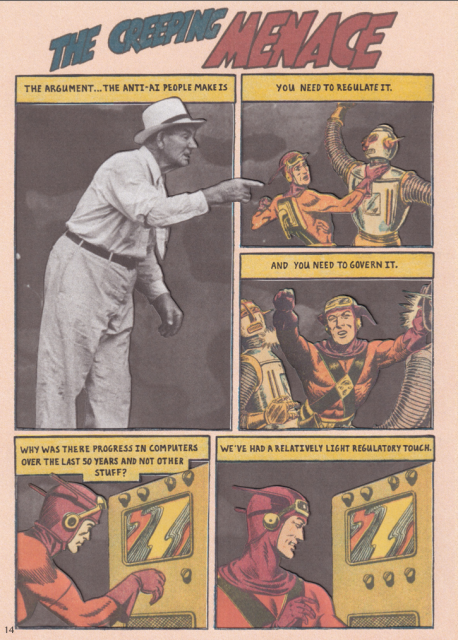

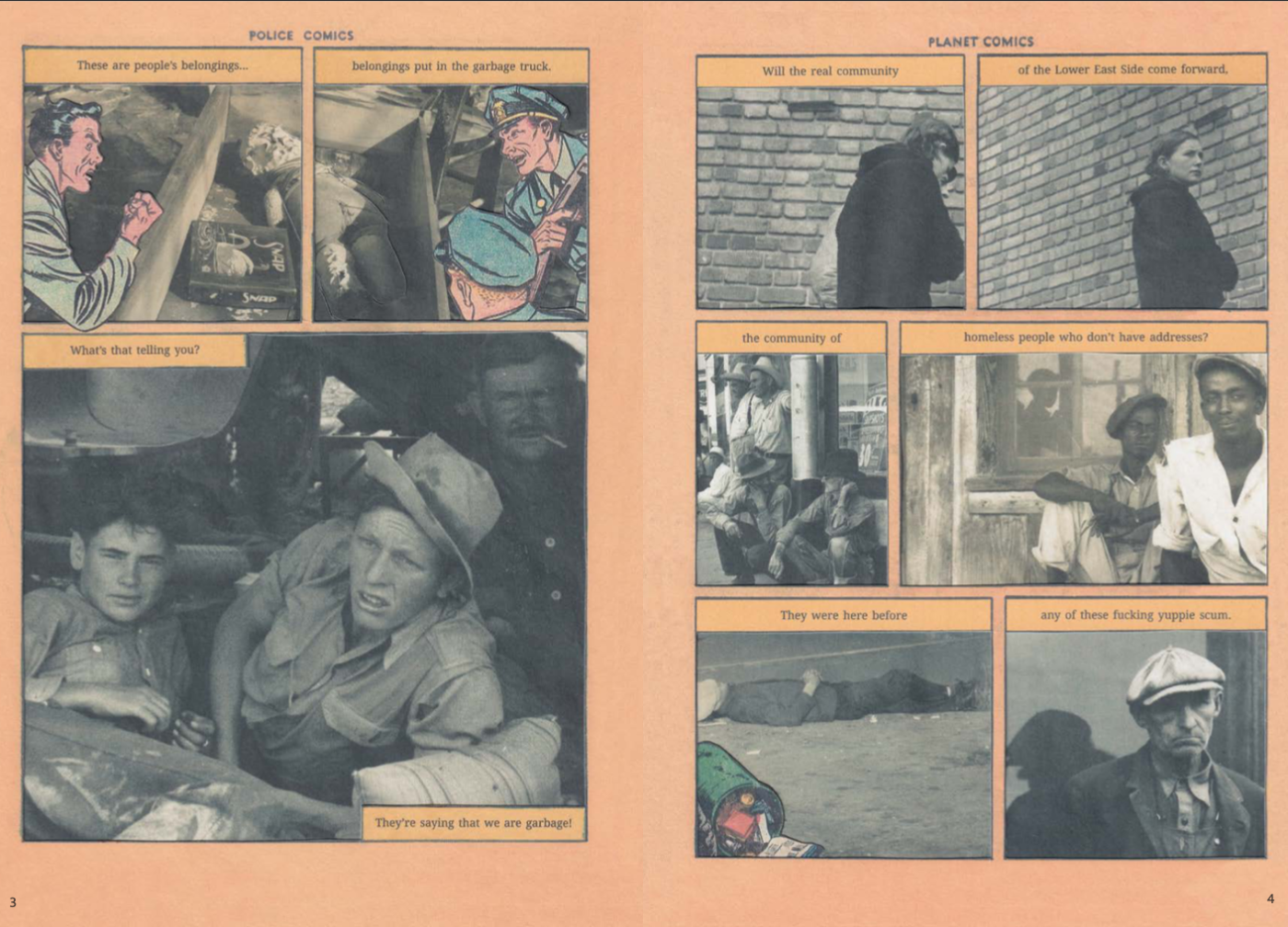

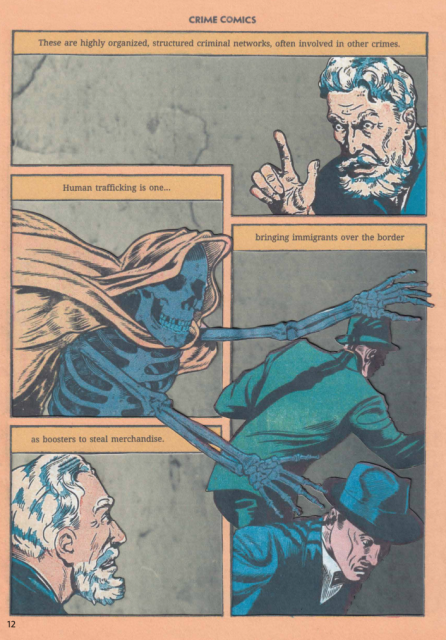

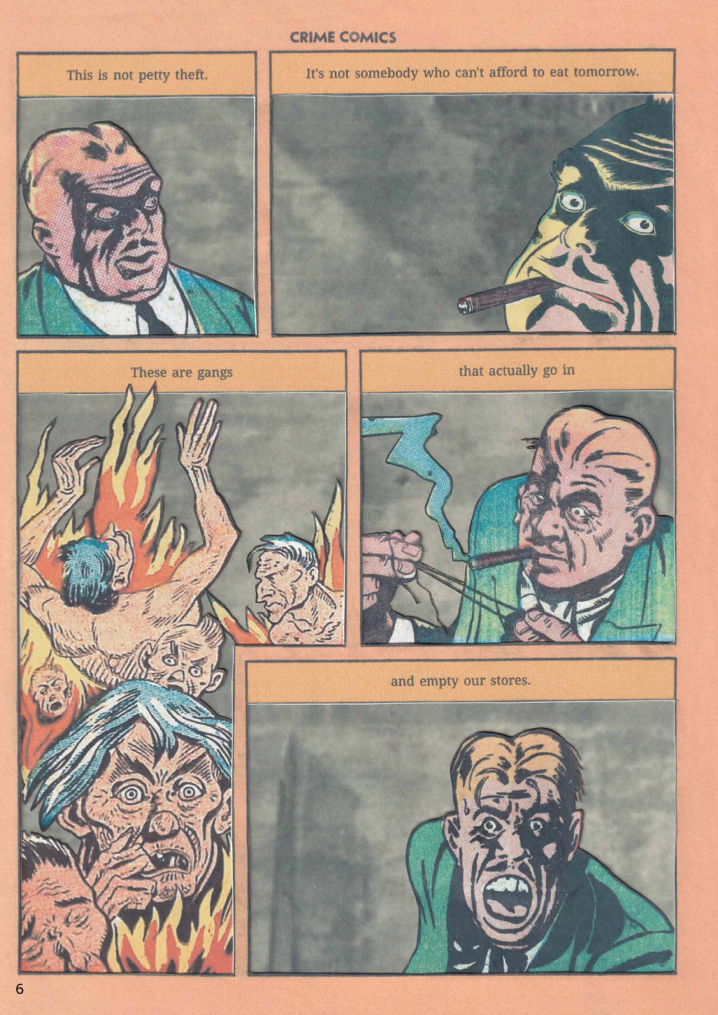

I’ll start with process. My work is research based, with all the text being direct quotation. So, for Technocrat Tales, the text comes from public statements of tech billionaires. For "I’m a Cop," I use statements from U.S. police union leaders. Others of my comics—Monster Crime, Riot Comics, Failure Biographies—function a bit more as oral histories, so have a wider range of sources and voices.

Using collage, I combine these quotes with elements taken from old horror and sci-fi comic books, as well as photographs from the Great Depression. I physically make the pages using scissors, an X-Acto knife, and glue — touching up each page with a pencil and lastly, with Technocrat Tales, lettering in the text.

As for perspective … okay, nobody seems to like this term, but I’m going to use it anyway. I think I make educational comics. Despite having a fairly minimal word count, my comics go in-depth on a subject that I think is worth learning about. Technocrat Tales specifically explores the worldview and future visions of the tech billionaires who run Google, OpenAI, Meta, Tesla, Palantir, etc. Big Tech is currently burrowing its way into every aspect of our national infrastructure (education, healthcare, policing, military, etc.) and our lives. So, it feels crucial that we understand their plans for us.

Educational comics might sound boring, but I also make weird comics. Combining old pulp sci-fi comics with something Mark Zuckerberg said on a Joe Rogan podcast is pretty weird and maybe even kind of funny. So, this weirdness relates to my perspective as well. Let’s go with "Weird Real-Life Educational Horror Comics." I think I’ve created a new sub-sub-subgenre!

What do you think is the stigma around comics as an educational medium?

I grew up as a punk rock kid, so I certainly wasn’t interested in associating comic books with school or authority. There’s also historical baggage, probably dating back to the deeply uncool comic books put out by Parents Magazine in the forties and fifties and stuff like Spider-Man being used for anti-drug messaging. This created a lingering stigma. But, you know, zines have long been used for grassroots educational purposes, and today, I’d say there are actually some pretty good explicitly educational comics for kids. But it can still feel odd to allude to “education” in an indie comics space.

I think it’s the use of direct quotes that makes your work so uniquely insightful. Do you find those to be an abstracting or an orienting asset to the final product?

Orienting, I hope. I think it can be really hard to listen to what people are saying. We’re in a time of overload, with a constant flood of voices coming from our devices. It can feel difficult to stop long enough to truly listen to any one voice, particularly if that voice is saying something we don’t agree with. If nothing else, my comics are designed to help with this. Something about combining direct quotes with images that almost — but not quite — match up has a slightly destabilizing effect. Hopefully, this causes people to stop and listen. And to think about what kind of person could say such a thing.

Can you talk a little bit about the origins of your latest work and maybe offer a brief summation of how you define technocrats and technocracy?

I live on the outskirts of Silicon Valley and teach classes at a public university in the heart of Silicon Valley. It’s a hard place to live — crazy expensive and with massive wealth inequality — and tech “innovations” such as self-driving taxis and food delivery robots are often launched here first. I started seriously studying tech criticism a couple years ago. The activist-journalist Kelly Hayes had begun to talk about how organizers needed to start paying attention to what was going on with Big Tech, and around the same time, I was beginning to see generative-AI force its way into the classroom. Simply put, I felt like I needed to understand what was going on, and that was the first seed of what eventually became Technocrat Tales.

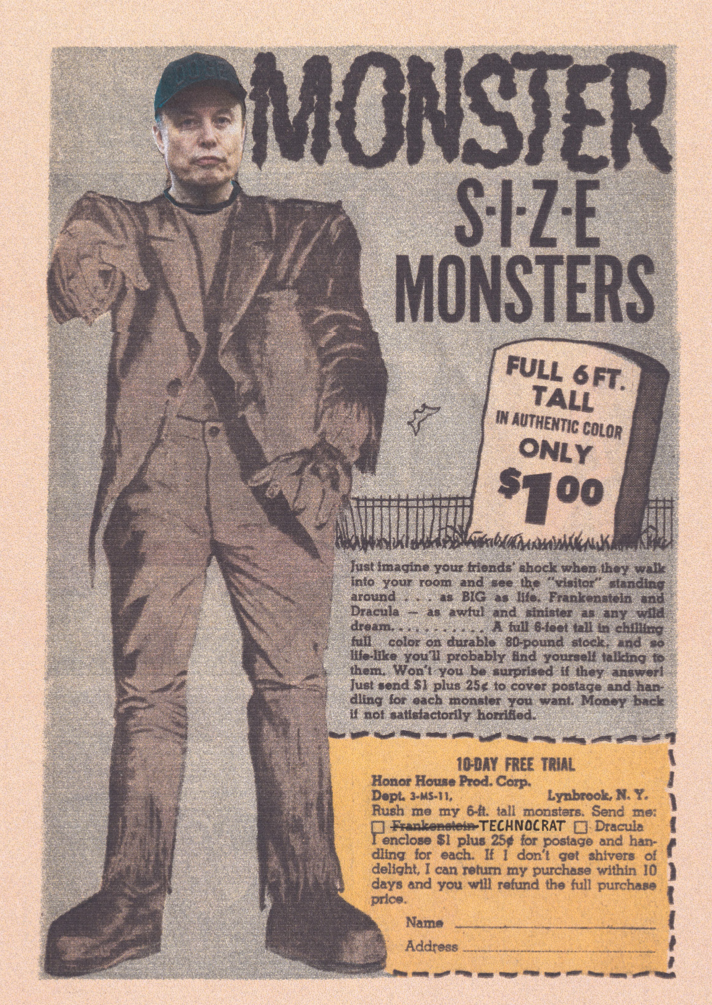

At our moment, there are so many horrors to fight against, but it strikes me that Big Tech is a central link connecting them. Consider, for example, Israel’s use of AI in their genocidal assaults on Gaza or the surveillance systems being used in ICE kidnappings. Consider how any hope to fight climate change is being threatened by the massive data centers being constructed to power AI. This is not even to mention Elon Musk’s months-long takeover of the federal government (which happened as I was trying to finish the comic book) or the fact that all the major tech companies have aligned themselves with the Trump administration and are gobbling up military and other governmental contracts as we speak. There are so many different battles that we need to fight right now, and the technocrats appear to be involved in all them.

Have you lived in Silicon Valley long enough to speak to what this evolution has looked like and how it has changed the physical, psychic, and economic landscape?

I’ve been here eight years. Silicon Valley had already transformed the area before I arrived. For the last three years, the town where I live has been named the most expensive rental market in the country. So, it only gets worse economically. While there are so many amazing, historic communities here and in the Bay Area, I’d say that massive wealth inequality has become etched into every aspect of the landscape.

Do you consider this work a pivot from your previous works, such as "I’m A Cop", or an extension of your previous work?

Definitely an extension. In "I’m a Cop", I used the statements of police unions to show the toxic worldview of policing, and in my new comic, I’m doing the same thing with tech leaders. Adding Monster Crime into this, all these comics are dealing with lies: the lies we’re being told about “safety” and the lies we’re being told about technology and the future.

Do you think delving into this territory was inevitable? What connections do you see between the valorization of police and the valorization of technocrats? Both, I think, are attributed to conservative thought, but, in your view, are these uniquely conservative phenomena?

In both cases, this valorization is explicitly based in fiction — in who controls the narrative. The U.S. and, really, global pop culture has gone all in for copaganda for as long as I’ve been alive. So, the worldview of policing that I consider toxic is reflected everywhere. This is a worldview that defines who we should be afraid of and who we should view as “criminal.” I regularly ask students to close their eyes, picture a “criminal,” and then to describe the person they see. They pretty much never describe an old white guy wearing a suit.

The people I refer to as technocrats are the tech billionaires who push their own narrative, and right now that narrative is overwhelmingly centered on the lie that we’re on the cusp of sentient AI, or super-intelligence, which will magically fix all the problems which they themselves are causing. The biggest lie of all is that we should trust them.

Is this uniquely conservative? Well, it’s not the small government conservatism that many of us were taught about in school. Both policing and Big Tech want a government that will give them endless funding. Using the government as an endless spigot of money isn’t “conservative” by definition. But unquestionably, both the police unions and the technocrats have aligned themselves with the extreme right. Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor have written convincingly that Big Tech and the far right have united into a singular force of “end times fascism.” My research for Technocrat Tales supports that conclusion.

From a zeitgeist perspective, do you think the needle has moved on criticisms of the police (or the influence of police) across the years in which you examined them in your work?

I think the 2020 uprisings definitely shifted the conversation around policing. Most surprisingly, the concept of abolition broke through into mainstream discourse. The first issue of “I’m a Cop” came out in 2022, and the effects of that shift were still very much being felt at that time. I’ve never had so much interest in my work as I had for that first issue.

Unfortunately, at the same time, there has been enormous pushback, with Republicans and Democrats both embracing increased funding for policing and embracing verifiable lies about rising crime rates. The good news, I think, is that more people than ever remain willing to question the value of policing. Most folks who were radicalized five years ago remain radicalized today, even if they might justifiably feel helpless at the moment.

What, if any, changes in the criticism or consideration of technocrats have you observed in putting this book together?

Well, Elon Musk certainly helped change things. I use a handful of Musk quotes in the comic but cut some others, because while I was trying to finish the comic, he was suddenly everywhere. DOGE and his work to destroy the federal government helped remove the veil. There has long been a mistaken assumption that Silicon Valley is fundamentally liberal, and I think Musk — the richest person in the world and the most iconic figure of Silicon Valley — has finally put that assumption to rest. More people than ever have become openly hostile to the technocrats, which certainly appears positive from my perspective.

Just this week an organizer contacted me to order copies of Technocrat Tales to be used in a teach-in as part of an event called “Stop Billionaires Summer.” People are definitely mobilized. The Tesla Takedown movement remains active, and I’m particularly heartened by the growing actions against Palantir, which is an openly evil company, even by Silicon Valley standards.

What do you make of technocrats increasing interest in cultural issues? I think a generation ago their concerns were focused solely on business and technology and now they are bankrolling content creators and buying social media sites. I think it’s obvious they see culture as the next frontier, but is it to manufacture consent? To impart a vision?

There are so many possible answers here. Most broadly, I think this is another example of particularly voracious capitalism, with tech companies pushing into all areas of potential profitmaking. So, for example, they “disrupt” (in other words, destroy) the music industry and so on. Culture is yet another area in which they can create wealth-hoarding monopolies.

But another factor is that technocrats appear increasingly comfortable with manipulating societal structures. Musk buying Twitter to force it right, Bezos and other technocrats buying newspapers: this is about social control. They have also worked their way into our infrastructure, literally into our governments. This about the richest people on the planet further amassing power. I think the current attempts to force AI into all aspects of our lives might represent the final frontier for them. Musk has repeatedly been caught programming white supremacist ideology into his Grok chatbot (or “MechaHitler,” as it dubbed itself). Sam Altman has said that we need a new “social contract” because AI puts “the whole structure of society itself … up for debate and reconfiguration.” I find that statement, and the ideology behind it, terrifying.

When did you see the potential in collage? Was it difficult to hone in on the source materials that make it work?

Along with being a comics obsessive, I studied art history in school. Seeing the collage comics/paste-ups of the artist Jess probably gave me the idea to try collage for comics in the first place. He took old Dick Tracy and western comic strips and made something radically different out of them. Also early on, I became really interested in how Jack Kirby used collage, placing the Fantastic Four or other superheroes over these elaborate photo-collages. Will Eisner did a bit of this too, particularly in PS, his magazine for military mechanics. Their combination of drawn figures and photography is really striking.

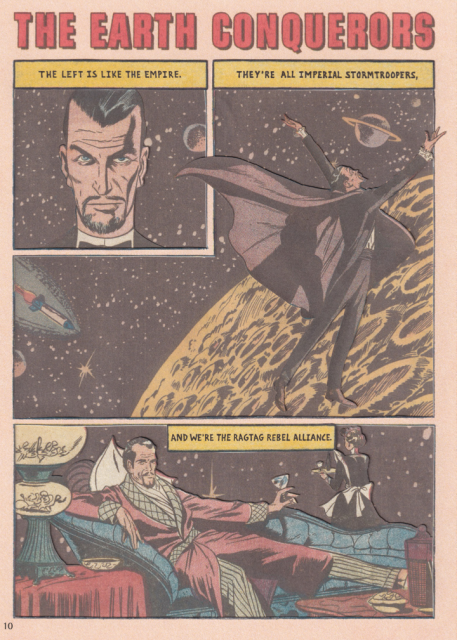

For me, yes, the source materials are crucial. I started using horror comics because they echoed the rhetoric of police unions, who consistently describe U.S. cities using horror tropes. For Technocrat Tales, I decided to use sci-fi comics because technocrats describe the world using the tropes of science fiction and video games. Tech billionaire Peter Thiel, who’s been deeply influential in fusing Silicon Valley with the far right, bizarrely describes Trump and technocrats as “the ragtag Rebel Alliance” from Star Wars. Elon Musk has been claiming for years that we are all living in a video game simulation. So, outlandish sci-fi definitely felt like the right source material.

What appeals to you about applying that technique to the comic book format?

There are a number of us combining collage and comics right now, but I’m the only cartoonist I’m aware of who consistently uses outside text as part of the collage process. Collage comics tend to be abstract in my observation, and there’s some great artists/cartoonists doing that work. In any case, making new comics out of old comics brings comic book history into it. Collage comics have a distinct way of interrogating and playing with our associations with that history and with the medium itself. As I’ve said, I’m obsessed with comics (and incidentally teach a class on comics history), so this is all appealing!

What do you think is gained or lost in this format?

More broadly, I’d say that comics are the perfect medium for challenging material — for disturbing histories, for unsettling ideas. The simple reason for this is that we’ve been conditioned to find reading comics as easy. With the possible exception of a comic that has an abnormally large amount of words, you almost never hear someone refer to reading a comic as “hard,” as people do with books, articles, and most other forms of reading. And weirdly, this is despite the fact that comics are enormously complex formally. Time doesn’t make sense on the comic page, the transitions vary wildly, etc. Readers have to do a lot of work to fuse all the elements of a comics page into a coherent whole. They have to do a lot of work to simply read the thing, but inevitably, they still feel that this work is easy.

I think that’s a real power of the medium. Because if readers automatically breeze past the formal challenges of comics, why shouldn’t this also apply to subject matter? Why would we assume that comics readers don’t want to be challenged in this area as well? I guarantee you that people will find Technocrat Tales an easy, fast read, but that doesn’t mean that the material isn’t also difficult to think about and grapple with. To me, that’s comics.

From a process perspective, have you developed a shorthand for putting your books together? Do you catalog or bank images and backgrounds?

Everything is files, both physical and digital. I begin every project with the quotes. For police union leaders, I keep an ever-growing file of press conference transcripts, social media postings, basically anything they say that appears notable to me. For the tech billionaires, I mainly read and listen to interviews (which is tedious: these guys ramble!), again adding anything notable they say to a growing file.

I also have large files of scans of old comics — scans that I’ve done myself and, when high resolution enough, scans from the massive repositories at the Digital Comics Museum and Comic Book+. Those sites and the community that scans and uploads the comics there have done so much to help my understanding of comics history, and I’m now fairly dependent on their generosity. The backgrounds come exclusively from photographs of the Farm Security Administration, the New Deal agency that sent photographers around during the depression, mainly the photographs of Dorothea Lange. I’ve got another huge digital file of these photos, sourced from the New York Public Library. So, when it comes to making comics pages, it all starts with hours and hours of simply looking — flipping through physical comics and clicking through scans, looking for something that echoes in some way with the quotes.

Perhaps it is too nebulous a question, but what makes for a satisfying contrast or juxtaposition?

This can shift from project to project, but I tend to try for grim humor. That’s definitely the case for Technocrat Tales. When Mark Zuckerberg talks about the importance of “masculine energy,” I depict him as a man on fire. For Elon Musk’s complaints that “empathy” is “a fundamental weakness of western civilization,” I depict him as a weird alien giving a lecture to human children. And then at the end, the alien figure takes off its mask, revealing a sad-looking middle-aged man. That’s funny to me, but also deeply, deeply disturbing.

Many of the most beloved narratives in pop culture turn on characters that have become synonymous with their professions in law enforcement, many of whom have become very recognizable. Do you think the type of collage in your books works better with generic figures? How do you find yourself modulating specificity in service of the message or the reach of the message?

Good point. We most often connect with narratives through character, and we certainly love “law enforcement” characters, whether literal cops (Green Lantern, Hawkman/Hawkgirl, etc.) or self-appointed vigilantes who police (basically every other superhero).

Every comic book I make uses figures (as well as other elements) taken from dozens of old comic books. A single page might use figures from as many as three or four different comics. So, there’s no singular figure for the reader to hook onto. Add to that the fact that my comics switch between multiple voices from page to page, and there’s certainly little sense of “character” to be found. I’ve actually never thought about this…

I guess I would say that each of my comics is essentially an essay, perhaps more like documentary films built around archival material rather than what you typically see in comics journalism or other nonfiction comics. So, the specificity comes mainly from the construction choices. In other words, the specificity is in the sense that there is a single hand that has made this thing, and the person who controls this hand is talking to the reader through these choices. Even though I don’t use my own words or even my own drawings, my hand is unmissable on the page. Through my construction choices, I’m conveying a point of view, and in the comic as a whole, these choices also make an argument.

Do you build images around page layouts or vice versa?

This has changed over time. For several years, I started each page with a scanned page of a comic I own. Most commonly, I used two issues of a great pre-code comic called Planet Comics for this. I’d print out the original comic’s page on my shitty printer, slice out everything from inside the page’s panels, and then I’d refill those panels. In other words, I made myself stick to preexisting page layouts as part of my process.

I don’t do that anymore. It got a little too restrictive. I still start with scanned pages, but I use Photoshop to adjust, size, and shape the panels around the images I plan to use. I also use Photoshop to experiment with construction ideas before I print things out and begin cutting.

How do you keep this process interesting to yourself?

The research process still excites me. I choose a subject, first of all, because I’m trying to teach myself about it. As for making the pages, I always find ways to challenge myself and try out different techniques. The first issue of “I’m a Cop” is quite spare and visually quiet, which probably adds to its unsettling quality. Since then, I’ve been increasingly interested in using a more conventional comics rhythm. Specifically, I became really interested in playing with comic strip beats in my pages. This might have something to do with chronologically reading every Peanuts strip a few years back.

With some comics, I challenged myself to use the photographs more — to mix in photographic figures with comic figures. I did that in Riot Comics and brought it back again in Technocrat Tales. I also used hand lettering in Technocrat Tales and expect I’ll use it from here on out. I’d initially wanted my text to look like it was typed onto/into the page, but for Technocrat Tales, it felt important to further emphasize the presence of a living, breathing artist. Using my handwriting felt like a way to do that.

With regard to beats, are you trying to emulate or obfuscate the rhythms you have observed? What insights did you note upon reading Peanuts?

There’s a short lecture that I sometimes give to creative writing or comics students, where I demonstrate how a Peanuts strip can be read as a sonnet. In the four-panel structure, Schultz tends to use the third panel for the “turn” (or “volta” as it is often referred to in poetry). This is the panel where something shifts or changes. If there is a surprise, it takes place here. So, this panel is the crux of the strip, but then there’s the fourth panel. And while this panel is supposedly the punchline, gag, conclusion, or whatever, Schultz often puts nothing funny in the fourth panel. Often the fourth panel is quite grim: Charlie Brown once again realizing that he is fundamentally alone or some other reminder that the world can be cruel and indifferent.

I don’t mean to suggest that Schultz is unique in this. Apparently, the use of a third panel twist or turn has been standard in Japanese comics, and this can also be considered a classic joke structure. But for the first ten to fifteen years of Peanuts, in particular, you can feel Schultz actively experimenting with the confines of this structure and often using the structure to either thwart the easy laugh or to avoid laughs all together. Thinking about this has been incredibly constructive for me.

Is self-publishing a way to circumvent any pushback on your appropriation of source material or is it to facilitate immediacy?

Immediacy. I almost entirely use comics from the public domain for source material, but even if I didn’t, my comics are transformative enough (and pull from so many different sources) that I’m confident that they qualify as fair use. That being said, I’d love people to check out the original comics, which are mostly available to read online, and have a massive citation list with links which I’m working on for my website and plan to include in any future collection.

I began publishing my own comics for a variety of reasons: most of my favorite cartoonists self-published, the publisher that put out my first two books stopped publishing, and most of all, I needed to publish the work fast. Since the first issue of “I’m a Cop,” I’ve been trying to make comics that apply to our current moment — to today — so self-publishing the comics very quickly has been crucial. That being said, I do miss working with publishers and editors. Having other eyes on your work and having other people make decisions: that’s incredibly helpful. And I find self-promotion exhausting. So, while I plan to continue to put out comic books myself for the immediacy you mentioned, I think I’m also ready to look for a new publisher.

Are you satisfied with the tools and platforms that you have used in self-publishing?

I was fortunate that the publisher of Failure Biographies asked me if I wanted to try to design that book myself. They taught me how to use InDesign and guided me through every step of the process. That was really generous and part of what gave me the confidence that I could design my own comics as interesting physical objects. The hardest part, really, is promotion, simply getting your work out there. I’ve been fairly fortunate in finding readers, but the state of social media is… challenging. Big Tech is, of course, a central player in these “tools and platforms,” so that doesn’t bode well for the future. For the last couple years, I’ve been trying to table at zine and comics festivals more often. Community feels more important than ever.

Has engaging with the collage process yielded any surprising revelations in your view of the subject matter or in your creative process?

When constructing my comics, I almost always discover something about the subject that I hadn’t suspected when I began. Monster Crime, which I published last year, traces the myth of a retail crimewave. Stitching together the voices and images, I learned a lot about how lies work and about how lies can grow into a dominant cultural force. I felt like I finally understood the process by which a lie morphs into a widely accepted truth.

With Technocrat Tales, I don’t think I’d realized just how fully apocalyptic and anti-human Silicon Valley has become until I actually read through the finished comic.

With collage, the other aspect is that I’m working so intimately with old comics. Along with cutting, I typically retouch linework with a pencil, and as I do, I’m constantly thinking about how this penciler, inker, and colorist worked together seventy, eighty years ago and how, at times, they appear to have been working against each other. I also think about the printing process, about decay, about the physicality of it all. This yields revelations as well.

The other side of your career includes work in an academic setting. Can art access levels of commentary that academic work can’t?

I think art lives in different spaces than academic work, and we “read” it far differently. Despite all the problems with the university system and my sometimes fraught relationship with it, academia remains a crucial source for revolutionary thinking. Angela Davis has spent almost all of her career working at universities. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote all his most seminal works in an academic setting. The vital counter-histories of Howard Zinn and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz came out of academia.

But with comics, specifically, there’s a deeper level of connection between the work and the reader. I talked earlier about the association between comics and easiness, but there’s also an association with comfort. Maybe this goes back to how literacy begins with babies studying picture books, how natural it feels to read between text and image. Or perhaps it’s purely cultural. But in any case, comics unlock a different part of the reader’s brain than academic writing does. So, comics are a perfect medium for commentary and argument. Comics are a perfect medium for politics. Comics are a perfect medium for hard, challenging ideas.

So, please, let’s use comics that way.

The post ‘Comics are the perfect medium for challenging material’: An interview with Johnny Damm appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment