Ilan Manouach is a Greek-Belgian artist, researcher, and publisher known for his experimental and conceptual work in the field of comics. Born in Athens in 1980, he learned to make comics at the Saint-Luc art school in Brussels during the 1990s—an institution with an impressive alumni list that includes Benoît Sokal, François Schuiten, and Thierry Van Hasselt. Although active for less than two decades, Manouach has carved out a unique position within the European comics landscape. To some, he is a plagiarist and provocateur; to others, a vital voice who explores the interstices of the comics medium—its formal and expressive affordances, as well as its political, economic, and social dimensions. This is one reason why poet and critic Kenneth Goldsmith, in a recent scholarly anthology devoted entirely to Manouach’s work, labels him “our twenty-first century Marcel Duchamp.”

Yet summarizing Manouach’s work is no easy task—partly because he seems to take pride in resisting the notion of a consistent personal style or unified artistic voice, the kind of red thread typically expected to run through an artist’s oeuvre. Instead, the common denominator in his body of work is a playful impulse to disrupt established orders and put everything at stake. He does this by operating at the intersection of art, literature, theory, and technology, constantly challenging conventional ideas about what comics are and what they can become. For Manouach, nothing is sacred—everything is open to disruption.

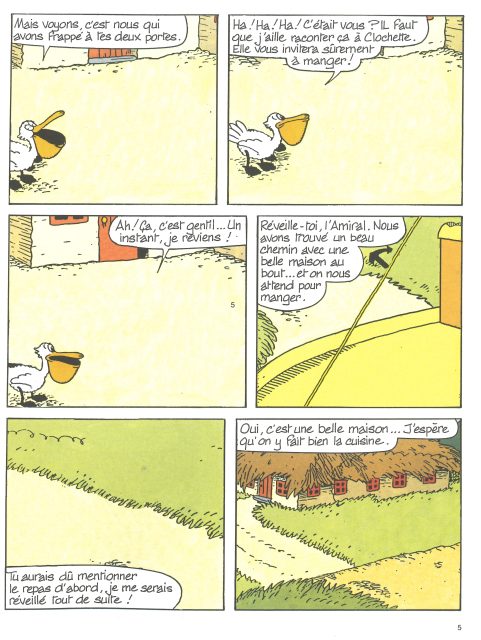

It is hard to find a better example of Manouach’s conceptual approach, and provocative nature, than Katz (2011), in which he redrew the heads of all the animal characters in Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991), replacing them all with cats. This “pirated” edition—visually identical to the original except for the animal switch—was exhibited at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in 2012, the same year Spiegelman served as its president. In the Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, Spiegelman famously depicts Poles as pigs, Jews as mice, and Germans as cats, narrating his father’s memories of the Holocaust and its surrounding events. According to Xavier Guilbert, Manouach’s intervention raised critical questions about the adequacy and implications of Spiegelman’s representational system—particularly the risk of essentialism inherent in using animal metaphors to denote religious, national, or ideological identities such as Nazis and Jews. However, Spiegelman’s French publisher, Flammarion, were not impressed and sued Manouach for copyright violation, and he was forced to destroy the remaining copies (including the digital files which led to yet another project: MetaKatz where the title is no unsubtle nod to Spiegelman’s book MetaMaus).

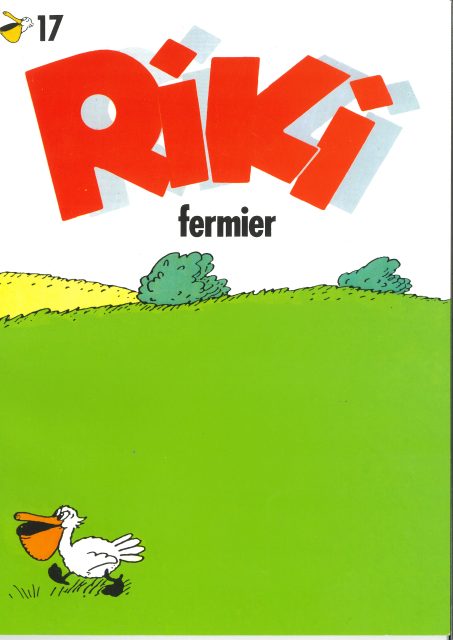

Katz can also be understood in light of Manouach’s engagement with the experimental practices of Oubapo—the comics counterpart to the French literary group Oulipo—which, in Thierry Groensteen’s definition, involve modifying existing comics. In addition to Katz, another example of Manouach’s Oubapo-inspired work is Riki Fermier (2015), based on the Danish children’s comics series Rasmus Klump (known as Petzi in French). The original series follows the adventures of Petzi the bear cub and his companions: Pingo the penguin, Riki the pelican, and L’Amiral the seal. Manouach’s intervention erases all supporting characters and redirects every line of dialogue to the pelican, transforming the narrative into a disjointed monologue. The result recalls the webcomic Garfield Minus Garfield, in which the smug, lasagna-loving cat is removed from every panel, leaving his owner Jon to speak endlessly into the void. In Riki Fermier, the outcome is a similarly estranged reading experience—one that reflects on themes of isolation, loneliness, and the underlying mechanics of narrative construction. All alongside strong elements of humor.

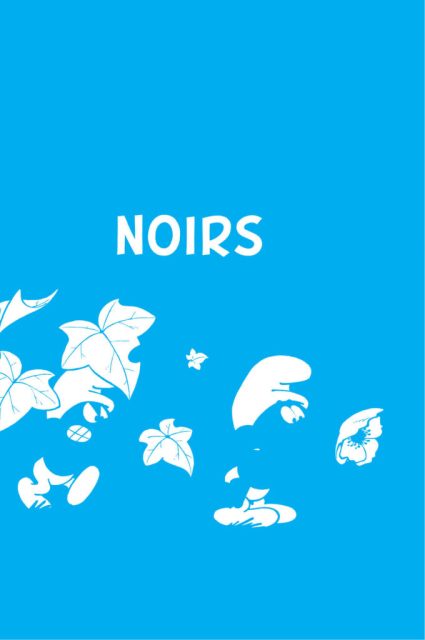

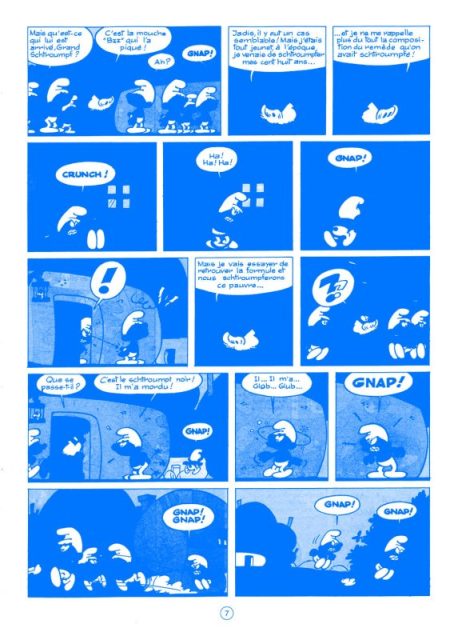

Manouach has also directed a critical gaze toward canonized characters and works within the Franco-Belgian comics tradition, most notably in Noirs (2014), his response to Les Schtroumpfs Noirs [The Black Smurfs] from 1963. In Peyo’s original comic, the appearance of a “black” Smurf in the village is laden with racist undertones—evident both in character design and narrative function. In Noirs, Manouach reprints the original album using only four shades of cyan, deliberately omitting the standard CMYK color separation (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) typically employed in offset printing. This minimalist intervention renders the visual field unstable as pages are covered in solid blue: readers can no longer distinguish “black” Smurfs from “regular” ones, nor clearly separate foreground from background. Onomatopoeias, captions, and panel boundaries blur together, producing a disorienting and unreadable visual experience—one that also serves to obscure the original’s racist message.

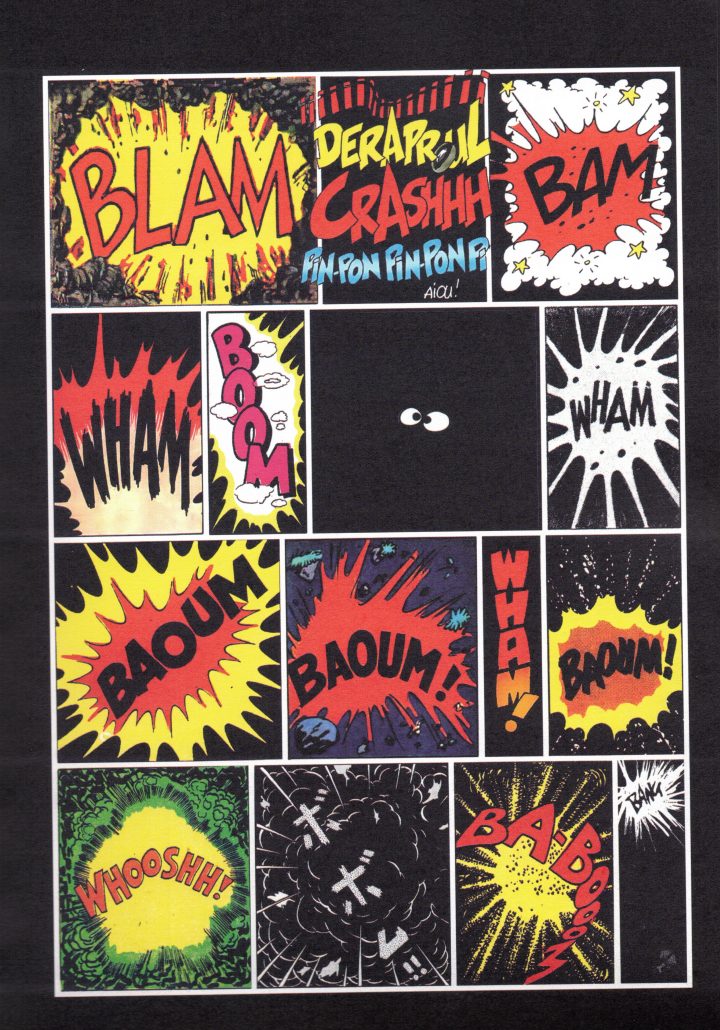

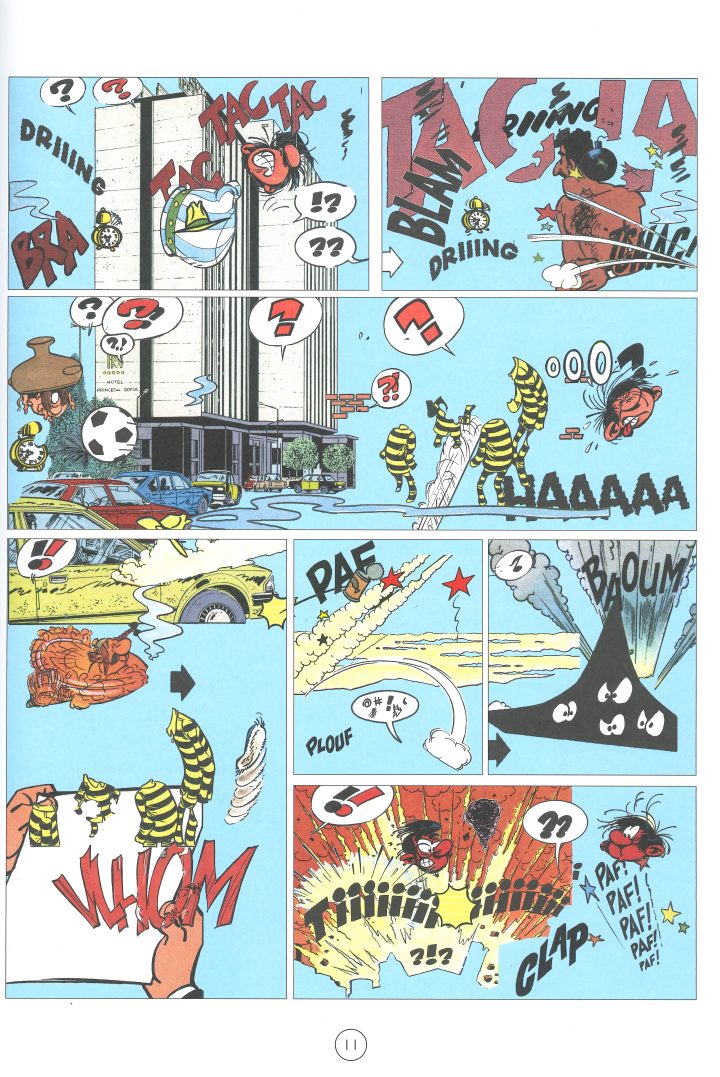

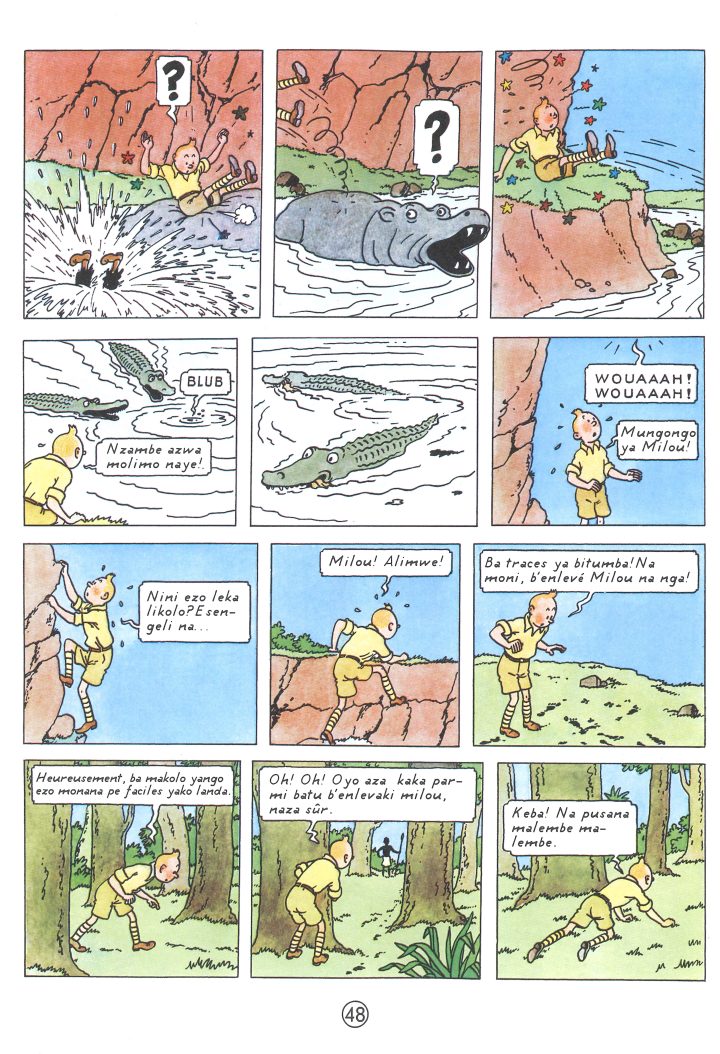

In a similar vein, Manouach has translated Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo—an album saturated with colonial propaganda—into the Congolese language of Lingala (Tintin Akei Congo). And in Abrégé de la bande dessinée franco-belge (2018), he draws on the iconic 48CC format (forty-eight color-printed, hardcover pages) that has long defined the industrial standard for mainstream comics in Belgium and France. In a single afternoon, Manouach acquired forty-eight 48CC albums from second-hand shops. After close reading, he compiled list of recurring elements in Franco-Belgian comics. This inventory of proto-memes, meta-narrative devices, and paratextual tropes—Gaston’s head, Obelix’s pants, the Daltons’ prison uniforms, alongside storm clouds, football badges, racial stereotypes, and more—forms a visual index of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition. And of course, everything is drawn in ligne claire.

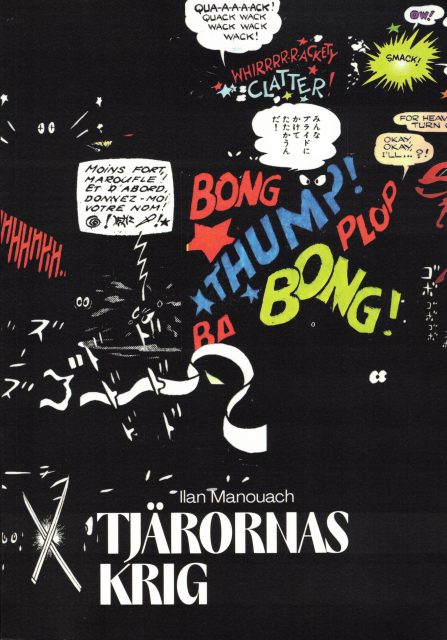

His most recent book, Tar Wars, operates in a similar fashion, constructing a fragmented narrative entirely from panels appropriated from an extraordinarily vast range of comics. All of these panels are heavily blackened, containing only speech balloons, captions, onomatopoeias, and visual effects such as explosions, lightning bolts, rain, scribbles, and sparks. Despite their fragmentary nature, the panels are arranged in a way that suggests a coherent-albeit hallucinatory-narrative progression: it begins with a series of “Big Bangs!”, followed by unseen characters exchanging glances, speaking (predominantly in English and French), screaming, fighting—and finally, briefly waking from the nightmare.

There are many more books worth mentioning—so many, in fact, that it can be difficult to keep track of them all. In 2024 alone, Manouach published no fewer than four titles. At the time of writing, his body of work comprises over twenty-five books, including his widely discussed project based on One Piece, billed as the longest book ever produced. In this work, Manouach assembled the entire run of Eiichirō Oda’s One Piece into a single, monumental volume weighing 17 kilograms and spanning 21,450 pages. By creating a book that is essentially unreadable, Manouach sought to underscore the dual nature of comics as both commodity and literature.

Another of his best-known works is Shapereader, an experimental tactile system designed for blind and visually impaired comics readers. In recent years, Manouach has also emerged as a vocal advocate of generative AI—or “synthetic comics” in his vocabulary–which he has used to produced several notable works, including The Neural Yorker, which plays with the format and visual language of The New Yorker cartoons; Lu 0, a compilation of panels from the comic Little Lulu without any human figures; and a contribution to BD Cul, Le Monte en l’Air’s series of erotic comics. It is highly likely that, by the time this text goes to print, he will have published at least one or two additional works. In addition to his artistic output, Manouach holds a PhD in New Media from Aalto University, Finland, and has published a number of scholarly articles on the comics medium. He also runs the non-profit organization Echo Chamber devoted to artistic research on comics.

The interview was conducted over the phone at three different occasions between March and June 2025. The transcript has been edited for clarity.

AMAN: Let’s start with a question driven entirely by personal curiosity. Given the conceptual nature of your own work, what kind of comics do you read yourself?

MANOUACH: I mostly read manga. Actually, about 95% of the comics I read are manga. I buy new releases, of course, but since I live in Brussels and spend a lot of time in secondhand bookstores, I also end up picking up a lot of old manga. I enjoy grabbing a random volume from a long-running series—without knowing what came before or what comes after.

What’s the appeal of jumping into, say, volume 22 of Berserk?

I find it fascinating to enter a narrative world without any context—no assumptions, no prior knowledge of what’s happened or who the key players are. It’s a bit like starting season two, episode four of a Netflix series. It creates a kind of productive alienation. You become a detective: trying to figure out who these people are, where they come from, what drives them, what their ambitions are. I’m really intrigued by narration in comics.

It sounds like you have your researcher hat on when you read your randomly selected mangas. But when was the last time you went to a comics shop because you knew a particular cartoonist had just released something you really wanted to read?

Honestly, I never do that.

Never?

Not in the past ten years, at least. That said, I live close to Multi BD, a big comics store in Brussels. One of my former roommates works there, and I often ask him to recommend new titles. That’s usually how I end up reading new comics. I don’t follow the specialized press or stay active on social media, so I’m pretty out of the loop when it comes to current releases. But I do go to bookstores almost every day—or at least four times a week. I don’t necessarily buy something each time, but I really enjoy browsing, especially in a country like Belgium where comics publishing is such a big part of the culture.

Can you name a recent comic you’ve enjoyed?

I really like Humunculus by Hideo Yamamoto. The series follows a homeless man who undergoes an experimental brain surgery called trepanation, which allows him to see people as distorted creatures that reflect their inner psychological states. It was out of print for a long time but has recently been reissued by an American publisher. It’s absolutely fascinating. I am currently reading another of Hideo Yamamoto’s works called Hikari-Man.

Do you have any favorite cartoonists?

I grew up reading a lot of American underground artists. Ben Katchor is one of my favorites. I’m a big fan of Robert Crumb. I also really admire Bill Griffith, and Kim Deitch—especially his really strange work. In general, I gravitate toward artists who push the boundaries of the medium. Ben Katchor, for instance, has always felt misunderstood to me—even though he received a MacArthur Genius grant. And Bill Griffith, honestly, feels like one of the great minds of American literature—not just comics.

When I was preparing for this interview, I noticed there’s very little publicly available information about your early life. But I did read that you decided to become a cartoonist at a very young age. Do you remember when that happened?

I don’t remember a specific moment, but I do recall that by the time most kids at school were fifteen, they had some idea—at least vaguely—about what they wanted to do in the future. That wasn’t the case for me. I was a mediocre student, bad at most things, and had no real passion for anything—except comics. Comics were my only option; I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. But even then, I was a terrible comics artist. I had a good friend in Greece who was really talented, and seeing his work made me doubt whether I had what it took. Still, comics were the only thing I could picture myself doing.

So you kept going anyway?

Yes. I applied to Saint-Luc, the prestigious comics school in Brussels, and somehow I passed the entrance test and got accepted. To be honest, I think they accepted me for the wrong reasons—the selection committee seemed really excited that I played the saxophone. At the time, I was equally passionate about music, and Saint-Luc liked students who had interests beyond comics. But getting accepted gave me some confidence. By the second year, I started to think maybe I actually had some ideas worth exploring.

Back then, did you have a dream publisher you wanted to work with?

Absolutely. This was the late 1990s, and there was a lot happening in the comics world. In France, you had the nouvelle bande dessinée movement—artists who had mostly worked with L’Association were starting to gain recognition and publish with major houses like Casterman, Dargaud, and Delcourt. It was a pivotal moment when alternative comics began earning respect from the mainstream. And by “respect,” I mean they were becoming marketable—publishers realized they could actually sell.

Personally, though, I was a huge fan of Fluide Glacial—which I can’t really read anymore, but I adored it back then. I loved Gotlib, Hugo Pratt, Enki Bilal, and especially Foerster, who did these amazing horror comics. Early on, I had a clear idea of the kind of comics I wanted to make—funny, provocative stuff. But over time, those ideas became fuzzier, and eventually, I completely changed direction.

Before we get into your work, I’d like to learn more about your background. You grew up in Greece.

Yes, I was born in Athens and grew up there before moving to Belgium to study.

Was your childhood immersed in comics?

Absolutely. I read a lot of comics—I loved them.

You were born in 1980. What kinds of comics were available in Greece during the late 1980s and early 1990s?

I mainly read two magazines that acted like ambassadors, publishing a wide range of European comics from all the usual names. I also used to buy random comics in secondhand bookstores—ones I didn’t know anything about. Greece didn’t have a strong comics tradition, so I was really curious to see what was being published elsewhere. I was also lucky—my father traveled a lot for work and would bring back comics from wherever he went. That made me realize, even as a kid, that comics are a global form of expression. Every country has its own tradition.

What did your parents do for a living?

My mother was a tour guide, and my father was on the board of a pharmaceutical company. He was a manager, which is why he traveled a lot—to negotiate deals and so on.

So, you grew up in a middle-class environment?

Yes, very much so. It was a solidly bourgeois upbringing.

I read somewhere that you spoke French at home rather than Greek—is that true?

Yes, French is actually my first language. Both my parents are multilingual—my father speaks seven languages—so it was only natural that my brother and I would grow up bilingual at the very least. My mother always spoke to me in French. I guess it was part of that bourgeois upbringing.

In other words, it was a conscious choice on your parents’ part—to raise their children speaking another language, even though they weren’t French themselves?

Exactly.

Did you do any fanzines as an aspiring cartoonist?

No. I had no clue what fanzines were. I only knew comics from books and magazines.

Did you start working on a book project while at Saint-Luc? You published your first book, Les Lieux et les Choses qui Entouraient les Gens Désormais [The Places and Things that Now Surrounded People], in 2003, which must have been around the time you graduated.

It all happened very quickly. When I graduated from Saint-Luc, I had already finished my first book. What I actually did was take my second book—my graduation project, titled La Morte du Cycliste [The Death of the Cyclist]—and put it in the window of a bookstore here in Brussels. It was a large accordion-style book, about five meters long when unfolded. It consisted of images without any clear narrative links. I liked the idea that it could be read both as a book and as a visual strip when completely opened up. It was my way of breaking away from traditional storytelling—I wanted to leave room for broader interpretation.

The book featured recurring elements and motifs that disappeared and reappeared, forming a kind of visual language without a coherent linear structure. I printed around 20 copies, and one of them caught the eye of Christophe Poot, one of the publishers at La Cinquième Couche. He contacted me and asked if I was working on anything else. So I showed him the pages I’d been developing for Les Lieux et les Choses qui Entouraient les Gens Désormais. That’s really how it all started—just a handmade booklet in a bookstore window. You could almost call that display an analog version of Instagram! [laughs]

You were incredibly lucky. Very few cartoonists get discovered that way. Had you submitted your work to other publishers before La Cinquième Couche contacted you?

Oh yes, I’d sent my work to countless publishers and got nothing but rejection letters. I submitted Les Lieux et les Choses qui Entouraient les Gens Désormais to at least 15 publishers—L’Association, Cornélius, Atrabile—you name it. Nobody was interested. And it only got worse from there. The newer material I sent out was even less well received, mostly because it didn’t follow a traditional narrative.

Did you try Frémok? Your poetic storytelling and visual style seem like a natural fit—very reminiscent of Frigobox.

I did, but with no luck. However, at that point, Freón and Amok hadn’t merged yet. I think I felt more kinship to Amok, not that it helped me to get published. And yes, you’re right—the style was definitely in that vein. Somewhere between [Lorenzo] Mattotti and Christophe Blain. Mattotti, in particular, was a huge influence back then. I was really drawn to his work, although I don’t find it as interesting today. Still, that’s very much the tradition I was coming out of.

In the end, none of that mattered—you got published by La Cinquième Couche. What was the reception like for Les Lieux et les Choses qui Entouraient les Gens Désormais?

Actually, one person who really loved it was Thierry Groensteen. But he never mentioned it again—almost as if praising it had been an act of treason. The book had a narrative people could relate to, something more accessible than what I did later.

The first thing I read by you—which I only realized later—must have been your contribution to L’Éprouvette, L’Association’s collection of critical essays on comics. You had a comic in the third issue that came out in 2007.

Oh yes, I loved L’Éprouvette. I contributed a small story to one issue. Were you in it too?

I wish, but unfortunately no. I still enjoy reading them though. Jean-Christophe Menu’s editorial eye in combination with his knowledge of comics and polemical writing is almost a guarantee that any project he is involved in will be interesting, regardless if you agree with him or not.

I completely agree on Menu. And the three L’Éprouvette-books are fantastic. Probably the best critical writing about comics still out there.

You started out as an alternative cartoonist but quite quickly began producing the kind of conceptual work you're best known for today. What sparked that shift in your approach to comics?

I started working conceptually because I realized it’s almost impossible not to in comics. I remember publishing Frag in 2008, which was the last narrative comic I made. My publisher, Xavier Löwenthal, called me from the Angoulême Festival and said he’d sold 30 copies. My reaction was, “Really? Only 30 copies?”—because I had spent over a year working on that book. Today, 30 copies might feel like a small success, but back then it was disheartening. I didn’t want to spend a whole year making something just to have it disappear into the void. So I began looking for other ways to make comics—ways that felt more creative, that let me organize content differently, and that didn’t rely so heavily on a traditional idea of craft. That’s when I started working with existing material—Riki Fermier, Maus, the Les Schtroumpfs ”Noirs” album, and so on.

So are you suggesting that economics played a role in that transformation? That doing conceptual work helped you pay the bills — something that wouldn’t have been possible as a struggling alternative cartoonist?

No, no, not at all. Selling books is, in my view, a very antiquated model. Who actually makes money from selling books? Only a handful of very successful writers. Hardly any comics artists earn a living that way. For most cartoonists, the royalties they receive at the end of the year—after spending months or even years on a book—are absurdly low. They barely cover basic utilities.

Even if your book sells 2,000 copies—which today would be considered a success—it’s still not enough to live off. That’s why I began approaching comics as a form of artistic research, where the book isn’t the final product but just a phase in an ongoing process.

When I was in art school—and when the book industry looked very different—I was more preoccupied with sales figures and how to make a living as a cartoonist. My taste back then was also more commercial. But eventually, I arrived at the opposite conclusion: since you can’t realistically make a living from comics, why not completely rethink what comics can be? For instance, by challenging the old notion of craftsmanship, which has traditionally been seen as the only legitimate way to practice comics.

Let’s go back to one of the works you mentioned—Riki Fermier. Can you walk us through how that concept developed, particularly as you began removing the other characters from the book?

I had been reading works by the Oulipo group, especially Georges Perec’s La Disparition [A Void], and found the idea of structural constraints really inspiring. It made me want to see what would happen if I removed a fundamental element from an existing work. What remains when something essential is taken away? That was the question I was trying to answer.

At the time, I was also obsessed with a theatre concept I’d come across—though I never actually saw the play—by Carmelo Bene, the Italian director. He had reworked Romeo and Juliet by removing Romeo entirely. His questions were: Who is Juliet without Romeo? Who will she fall in love with? Why should the families still be fighting? That idea of subtracting a key component fascinated me—how the rest of the narrative must shift and reconfigure itself to fill that void.

Riki Fermier was the first book where I explored this. I removed all the supporting characters and redirected all the speech balloons to the pelican. This strange reconfiguration created a new way of reading the book—one that suggested alienation, loneliness, even paranoia. But honestly, it was also a way to pass the time. I was painstakingly cleaning the pages with the clone stamp tool in Photoshop, which was incredibly slow, all while listening to Roland Barthes’ lectures from his “Vivre ensemble” [Living together] series at the Collège de France.

How did your publisher react when you proposed this idea—removing all the characters from Riki Fermier?

They actually liked it. Xavier and William were both familiar with those kinds of literary references. They knew Oubapo, they’d read Perec, so they really got what I was trying to do. It became more difficult later on, but at that moment, they were very supportive. Eventually, though, I started to feel bored with Oubapo. It wasn’t giving me much anymore, so I moved in a different direction.

How did the book sell?

I don’t remember.

You would probably have remembered if it had been a success.

I mean, none of my books sell very well. I honestly can’t remember how much Riki Fermier sold, but I do remember it was reprinted once, which means we somehow sold out the first edition. But let’s be honest: most people don’t like my work very much. Few are interested in what I put out. Those who buy my books are usually from the art world—some even love it. Comics people generally hate what I do. Even back then, I remember getting the kind of reaction that would only grow stronger over time: How dare you touch someone else’s work? How dare you put your name on it and claim it as your own? The same criticisms and reactions I received last year with One Piece are the ones I have always encountered. What I do doesn’t sit well with comics people. What can I do? I would have loved for things to be different, but honestly, I’ve stopped caring.

Let’s discuss some of your earlier works in chronological order. One that, for many reasons, has received a lot of coverage is Katz. Could you take us back to the Angoulême Festival in 2012?

Since more than a decade has passed since those events, it’s not all fresh in my mind. First, I want to say that Maus is an amazing book—a real revelation when I first read it. However, there’s a problem: the book shows a certain complacency toward the codes of comics, codes based on binary forms of representation. As important as Maus is, I don't think it truly helped to deepen our understanding of the Holocaust or the destruction of the Jews. Spiegelman’s use of mice and cats made the book easy to read, easy to understand, easy to relate to—but the perspective was not the right one. Behind the animal characters, there’s a form of human essentialism: Germans and Jews come across as two completely different species. Maus is otherwise nuanced, but this polarity remains a serious flaw.

I wanted to revisit Maus and address what I saw as a major shortcoming. So, I wrote a letter to Spiegelman asking for his permission, this was before the Angoulême Festival. He responded to me four weeks after the festival was finished, expressing how deeply offended he was by my work. I had hoped to open a dialogue with him, but he wasn’t even willing to discuss. I genuinely wanted a conversation, an exchange of ideas. But the arguments he gave excluded any form of dialogue.

Then we heard from Spiegelman’s French publisher, Flammarion, who sued us. We had to destroy all the copies. They even sent someone to my studio to monitor me as I deleted all the digital files from my computer [laughter].

Did you have any interaction with Spiegelman during the festival?

Not at all. I do remember that my publisher, La Cinquième Couche, had placed the book all over the festival tents. As usual, the festival organizers took the president around on a tour, and they consciously tried to make sure he wouldn’t see a copy because they knew he’d be furious [laughter]. But no, he and I never spoke.

We were at the same event once in New York a few years later, but I didn’t get a chance to approach him. My publisher did run into his wife and daughter the year after Angoulême—they were both furious with me.

You’re suggesting that you’ve become persona non grata because of your conflict with Spiegelman?

Yes. And honestly, it still saddens me that we couldn’t have a real conversation about what I tried to initiate with Katz: a critical reflection on Maus. I’m not a moron. I didn’t approach this work casually—I had something to say. I wish Spiegelman had acknowledged that and shown some openness. I believe that truly important works can withstand and even benefit from being discussed in new ways.

Are you saying that greater openness on Spiegelman’s part could have introduced Maus to new audiences?

Exactly. I think it’s a sign of strength when a work can be reexamined and still hold its ground. Instead, he treated Maus as a brand that needed protecting.

When you were redrawing the mice as cats, you must have anticipated that some would see it as a blasphemous act, especially considering the status of Maus and its subject matter.

Of course. The point was never to be disrespectful. I knew it would provoke a reaction—that’s what made the work interesting. Katz isn’t particularly interesting in itself; it was intended as a vehicle for a larger discussion.

In hindsight, how do you view the reactions you received for Katz?

Well, Katz is the work that really got people to open their eyes to my work, because the reaction from the French publisher of Maus was so aggressive, so venomous—we had to destroy all the copies, delete all the files, everything. We even made a new book out of the controversy. At the same time, all this made Katz very famous. People were looking for it at the Angoulême Festival the following year; others got in touch wanting to buy it. Looking back, I see the controversy around Katz as both a blessing and a curse. Because after Katz, I’ve never had any problems with copyright again—despite the fact that I’ve done other works that could be considered even more problematic, like my Tintin book. I’ve never heard any complaints from Casterman about that one. Although, perhaps we shouldn’t even mention it—we might provoke them?

Translating Tintin

It’s a risk we’ll have to take, as I’m eager to learn more about your work on Tintin. That said, I have to admit I’m a bit surprised to hear that you haven’t received any complaints—especially considering that Tintinimaginatio (formerly Moulinsart), the rights holders to Tintin, are notorious for aggressively pursuing anyone who uses Tintin-related material. A few years ago, there was a widely publicized court case in the Netherlands where they sued a fanzine dedicated to Tintin.

Yeah, exactly. Recently, they even destroyed a small hair salon here in Brussels by suing them because they had a small drawing of Tintin on the wall. They are famous for doing that.

Why do you think they turned a blind eye to your pirate edition of Tintin in the Congo?

I think it’s because I touched such a toxic work that they probably figured going after me would only make things worse. It would bring unwanted attention to an album they prefer people forget. From that perspective, it was easier for them to just let my book pass. It turned out to be a smart strategy on their part because my book is still only known in a very small circle. Even though it has recently been reprinted, it won’t attract the kind of publicity that Katz did.

What prompted you to translate Tintin in the Congo into Lingala?

Tintin is one of the biggest entertainment brands in the world, and the Tintin albums have been translated into over a hundred languages. The album Tintin in the Congo is very famous in the Congo but is read in French. I wondered why they hadn’t translated it into Lingala, Swahili, or any other local language spoken there. Publishing the album in any of those languages would almost certainly make the rights holders a decent amount of money.

The conclusion I reached was that for Casterman and the Hergé estate, protecting the brand sometimes takes precedence over financial gain. All of this shows that they are very aware of how toxic the content of that album is. That’s why I decided to do it myself—to fill a corporate gap. I arranged for a translation into Lingala. The published book, Tintin Akei Kongo, actually made it to the Congo; we managed to get some copies distributed through the diplomatic community in Kinshasa.

Has it sold well in the Congo?

We’ve never heard back from the vendors, but I believe all copies sold out. The print run wasn’t very big—probably around 500 copies. The pricing was also contextual. The book sells for around 40–50 euros in Belgium, but around 10 euros in the Congo. I also think it was much better understood there compared to Belgium and France.

In what way was it better understood in the Congo?

Perhaps better isn’t quite the right word, but the people I spoke to in the Congo understood what I was trying to achieve by translating the album into Lingala—they recognized it as a form of postcolonial critique.

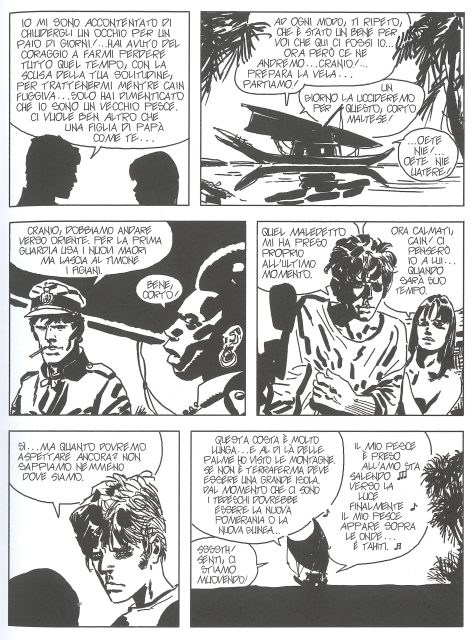

Another project of yours I’d like to discuss is your take on Hugo Pratt’s celebrated album La Ballade de la Mer Salée (Ballad of the Salt Sea) starring Corto Maltese. This is yet another classic European comic open to postcolonial critique as the white western protagonist dominates his surroundings wherever he goes in the world.

The background is that I had already completed a few projects through microworking—Harvester, Peanuts Minus Schulz, The Cubicle Island—where you contract people to perform specific, usually non-specialized tasks. You recruit them through labor platforms by describing the task and the skills needed. In those projects, one of the most active artists I worked with was from the Pacific Islands. That fascinated me, considering La Ballade de la Mer Salée plays out in the Pacific, with its romanticized colonial vision: Corto Maltese visiting exotic places, romancing local women, killing ”evil natives,” and so on. It made me reflect on the meaning of ”location” in comics. Comics have no intrinsic site; they are objects consumed wherever the reader happens to be. So I wondered: what would happen if I had the book redrawn in the place where the story occurs? Not in the safe confines of a European studio, but in the Pacific itself. I contracted a microworker to copy every page of Pratt’s book—including the cover, barcode, and price. The book was later published in collaboration with La Cinquième Couche and La Crypte Tonique, a small Brussels-based publisher. The downside is that I don’t think the barcode actually works, so it has very little circulation [laughter]. But hopefully, some readers here will get curious about it.

Similar to Katz, you see this book as a vehicle for a broader discussion. However, weren't you concerned that you might end up reproducing the very Eurocentrism you aim to critique?

Sure–but there are different ways of critiquing. Sometimes the most effective form is to repeat an action but from a new angle. It can be more powerful than simply waving a red flag and shouting ”toxic”, or ”problematic.” It’s the same logic behind Tintin Akei Congo. By translating the album into Lingala—a language of the people subjected to its racism—the suffering and the critique become much more visible.

Let me rephrase my question. In literature, we have examples like Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, a postcolonial prequel to Jane Eyre, Michel Tournier’s Friday a reworking of Robinson Crusoe, and Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation, which re-centers The Stranger around the murdered Arab.

I love those books—especially Michel Tournier’s work.

What these books have in common is that they reframe European narratives from the perspective of those rendered invisible. Wouldn’t it have been more effective to commission your Pacific Island microworker to retell Corto Maltese’s story from another point of view?

Maybe. I don’t know. My interest was more in exploring what happens to a story when it’s drawn in the place where it supposedly takes place, rather than safely at a distance. If Hugo Pratt had been forced to draw Corto Maltese from the Pacific, I think the story would have looked very different.

In what way?

For one thing, I think Corto Maltese would have shown more respect, and the depiction of the local people would have been far less exoticized. But I’m just speculating. I also recognize that some of the ideas behind the project are a bit half-baked. That’s the reality of being an artist—sometimes you succeed better at conveying your ideas than at other times.

That’s understandable, and I get that you want to open a debate or have a conversation with your work. However, you also render the artist invisible—which is part of a long-standing European tradition. Postcolonial scholars have pointed out how Europe has historically erased the labor of people from former colonies. Did you have any doubts about that?

Absolutely. I’ve never had a problem with the idea that, as a comics artist, you’re essentially a manager—you employ people to do the work. Many artists rely on anonymous contributors. For example, with my book Cubical Island, there were 1,500 people involved. Harvested was the same. The images were filtered and classified by anonymous workers. And I’m not the first to do this kind of thing. Given that I often work with other people’s materials, I honestly don’t believe that authorship is all that important. Even my own books are often unsigned. I frequently choose not to put my name on them.

Why not?

I created a website—comics.wtf—which showcases how comics artists typically portray themselves. If you go to the site, what do you see?

I see drawn images of predominantly white male cartoonists.

Exactly. And do you notice that the images don’t just show their faces, but also their tools? I find that fascinating. These drawings are almost always signed, because everything a comics artist does needs to be signed somehow. The pencil or the brush becomes part of their identity. Even in 2025, you still see artists depicted holding one. It’s part of the mythology.

And then there’s the signature at the bottom—I’ve never fully understood that. So, to return to your question, I think a signature is just a tool. You can use it or not, whether it’s your own work or someone else’s. I’ve put my name on projects I didn’t really do anything on, and I’ve left my name off work I spent months finishing.

And yes, you could ask—can you really make that decision on behalf of micro-workers too? And my answer is: I did. Yes.

Another work that has at least generated some attention, of course, is Noirs which is another famous example of racism in Belgian comics. In your book, you’ve rendered all the Smurfs in the same color which somewhat makes the racism less noticeable.

Yes, but the book doesn’t fully erase its racist dimension. What it does, rather, is make the discriminatory aspects harder to locate. The original work is obviously racist—there’s no question about that. And of course, we’re talking about Belgium in the 1950s. I mean, Belgians are racist even now—imagine what it was like back then. The book clearly mobilizes all the classic racist tropes: blackness is associated with evil, there’s a theme of contagion, one Smurf “buys” another, and eventually, they begin to replace the others. It’s one of the earliest expressions, I think, of the so-called “replacement theory”—a fascist idea that local populations are gradually displaced by outsiders, often imagined as Muslims.

So there’s a lot going on in that book. What I wanted to do was explore whether offset printing—usually just a neutral medium that transfers digital data to paper—could be used not just to convey information, but to shape it, even to change its political message entirely. By altering the color plates, we turned offset into something expressive, capable of interfering with how a book functions—how it communicates its message.

In this case, we made color no longer a key signifier for distinguishing good from evil. Of course, there are still other codes in play—like how the characters jump, or their teeth—but we wanted to see whether a single mechanical change, as simple as switching colors, could produce a different effect. And it worked. Even ten years later, I still find the result remarkably eloquent and minimal. The intervention is small, but it feels solid—it encapsulates a lot of what I try to say about books in general.

How did you come up with the idea?

I don’t know exactly. Honestly, all these different books stem from the fact that I never really felt at home as a comics artist. I found the whole practice tedious—too schoolish, too disciplinary. I didn’t want to spend years perfecting my drawing style, refining my storylines, or learning the whole canon of references. Comics culture is incredibly disciplinary, and when I say that, people get angry. They still like to imagine comics as a space of expression, of freedom, even anti-institutional. But that’s all bullshit. In reality, comics is a highly codified medium. And if you don’t follow the rules—if you don’t behave the way people expect—you get penalized.

Could you give an example of what you mean by “penalized”?

I remember when I did my version of Maus, I received hate mail from other comics artists—mostly from an older generation, maybe ten years older than me. They’re still around, by the way. And I’m kind of glad to see that what they chose to do—artistically speaking—is no longer viable. But their outrage was intense. It wasn’t about the reading my work offered, or the questions it raised. It was all about how I dared to “touch” Art Spiegelman. As if he were untouchable, sacred. That alone was enough to trigger them.

More recently, I was in Brazil giving a lecture, and afterward a student came up to me with 50 screenshots of comments on my Peanuts book. They were all incredibly aggressive—hate messages, demeaning remarks, full-on personal attacks. It’s hard to imagine this kind of hostility in other creative sectors, where people feel so strongly about how artists should behave.

It hasn’t escaped me either that you receive a lot of criticism—and even hate—on social media. It seems like something about your work provokes a particular kind of comics artist or critic, to the point where they start acting like schoolyard bullies.

Yeah, I’ve thought about doing a small booklet that compiles all those reactions. I find it fascinating how people often express themselves more clearly through hate than through appreciation. It’s like their feelings are sharper when they disapprove of something. You probably saw the comments on The Comics Journal in relation to my article?

I did.

The hostility was just so over the top—it didn’t even make sense. The Comics Journal ended up deleting some of the comments.

I’m sorry to hear about the abuse—you don’t deserve that. If we return to Noirs, what kind of reactions did the book get?

One unexpected person who praised the book was Peyo’s widow. I actually found it very interesting that she liked it so much.

Perhaps she saw the book’s racism as an unfortunate burden in Peyo’s career? At least he made a few attempts that could be interpreted as anti-racist, like Schtroumpf vert et vert Schtroumpf, where he satirizes the absurdity of ethnic conflicts by having the Smurfs split their village into a north and a south, separated by a heavily guarded border—just because they use different grammar.

I don’t buy that. Peyo was extremely racist and sexist. I remember reading an amazing book that includes a section on a meeting between Peyo and a couple of American businessmen who wanted to adapt the Smurfs into animated films. The book reproduces transcripts from the meeting, and it’s shocking how he talks about women. There’s simply no way around the fact that Peyo was a very problematic individual.

Did you hear back from Dupuis, the publishers of the original book?

Yes, I did—but only seven or eight years later. And it wasn’t much of a problem. It felt more like a letter they had to send for formality’s sake than anything else.

The role of racism in Franco-Belgian comics at large is one of the key aspects you managed to visualize in Abrégé de la bande dessinée franco-belge, published in 2018. What prompted your artistic shift from creating a single book to assembling a large corpus?

I was greatly inspired by Jean-Christophe Menu’s manifesto Plates-Bandes, in which he coins a specific term for Franco-Belgian comics that has become an important contribution to the field.

You mean ”48CC”?

Exactly. The term “48CC” helped make visible the specific material and formal conventions used in Franco-Belgian comics. Since “48CC” can signify different things to different people, I created my own list of elements associated with it—which ended up including around 200 items. Then I began visiting second-hand bookshops in Brussels and bought 48 classic Franco-Belgian albums—to stay loyal to the number. I started locating these listed elements in the books.

Could you give some examples of these elements?

Sure. We’ve already discussed racist and sexist iconography, which were two of them. Others included stylistic tropes such as exaggerated explosions, or recurring visual motifs like the four identical uniforms of the Daltons. I scanned all the books and grouped page one from each into one folder, page two into another, and so on. Then I removed everything not included in my list. When assembling Abrégé de la bande dessinée franco-belge, I used the panel structure from Blueberry as a base onto which I could paste these elements from across different books. It was a very time-consuming process. If I did it today, I would use machine learning tools to streamline the process.

The panels in the book are connected with a light blue color. Was that specific shade part of your list too?

Yes, it was! It became a sort of graphic score. Like any score, it needs to be performed in a specific space. The light blue was a way to provide context and cohesion for the various elements in the book. I experimented with different colors—white would have made the book more conceptual and less playful. The blue, though somewhat arbitrary, gives a sense of buoyancy. What do you think?

I actually like the sky blue. After reading your book, I now notice it every time I open a classic Franco-Belgian album. In fact, I’m currently working on a book about representations of the Other in Spirou magazine, and I keep spotting that exact shade—especially in Franquin's work.

Interesting. I need to revisit Franquin’s Spirou albums.

Back to Abrégé, your book arguably proves Scott McCloud right in saying that even if panels are randomly juxtaposed, readers will impose narrative meaning due to our pattern-recognition tendencies. Did you consciously try to create a readable narrative?

Not at all. I was simply playing with elements from my list. But I was curious to see what happens when you decontextualize them—whether they carry intrinsic meaning. Many of these images are so iconic that they speak for themselves.

Your latest book Tar Wars adopts a similar method, but this time focuses on black panels often used as backdrops for explosions.

Yes, there are definite parallels. But Tar Wars was more deliberate. Whereas Abrégé was about breadth, Tar Wars is about depth. Instead of 48 books, I drew from millions, using a big comics database compiled by my non-profit to allow targeted research. Tar Wars explores comics as a repository of human knowledge, focusing on black panels which appear in various moods—comedic, existential, dramatic. I removed them from their contexts to see what stories they could tell on their own. Like Abrégé, it’s built from emancipated blocks of comics where the images themselves carry the narrative.

When I read Tar Wars, I started thinking of Jochen Gerner’s conceptual work on Tintin in America, called TNT en Amérique. He also works with black panels, albeit in a deconstructive way—only a few recognizable signs of the original panels remain, but your brain still pieces them together as part of the narrative.

Yes, and that’s the difference. Jochen redraws everything. He still operates as an artist, as a craftsperson. But you have to approach comics not just as visual artworks, but as legal entities. Jochen even changed the title—it’s not Tintin but TNT—because he didn’t want any legal trouble with Moulinsart or Casterman.

And one thing we’ve learned by now is that you wouldn’t hesitate to throw their lawyers off balance.

Let’s just say I don’t share Jochen’s caution. His approach kind of misses the punch. By redrawing everything, he focuses solely on the visual dimension and neglects the legal one—which, in today’s comics world, is just as important.

Before we move on to the next book, I must ask: does your database include copyrighted material? I think I can guess the answer…

Absolutely.

Has anyone contacted you about using their panels?

Yes. At the most recent Angoulême Festival, I met Anna Haifisch. She told me that my book included two panels from her work.

Was she flattered or annoyed?

Neither. We’re on friendly terms. And I think this is actually one of the perks of my approach—it creates little surprises. Some people who are very familiar with comics look forward to my books as a kind of challenge: can they identify the origin of each panel? It sparks a real bibliophilic curiosity.

You hold a PhD from the School of Arts, Design and Architecture at Aalto University, Finland, and during your time there you developed Shapereader.

I had actually already started working on Shapereader before moving to Finland for my PhD studies. It was one of the projects I wanted to explore in my doctoral thesis. That made sense, since the project was initially funded by the Finnish Kone Foundation. For those who aren’t familiar with it, Shapereader is a comics object specifically designed for people with visual impairments. It consists of an expanding repertoire of tactile shapes that stand for characters, settings, objects, feelings, and so on. The reader is supposed to learn the “dictionary” of shapes in order to navigate the story. Besides the initial narrative called The Arctic Circle, I also created an ongoing workshop format that allows people to develop their own stories.

How has Shapereader been received and used?

For now, it’s mostly seen and used at exhibitions or events related to Shapereader, unfortunately. That said, there are plenty of YouTube videos made by people who have worked with the project, for anyone who’s interested.

Walk us through how you came up with the idea for Shapereader.

I’m a conceptual comics artist, and one thing we’ve touched on many times in our conversations is that comics, for me, are not only visual objects. For example, when I say there’s a major difference between TNT en Amérique and Tar Wars, I mean that in a purely conceptual way. They may be visually similar—both filled with black panels—but they are conceptually different. Appearance is secondary in that regard. So the challenge was to see if I could create a comic that isn’t visual, that addresses other senses. During a residency, I learned about a project on art and multilingualism, and things took off from there. I wrote a proposal for the Kone Foundation, and it was accepted.

You make it sound easy.

Most decisions that people take is because they are uninformed, they don’t know enough. At least, that’s the case for me: most decisions are usually taken because I know shit, it’s just some intuition that guides me. For example, when I started to work on Shapereader it was simply because I had this idea that I wanted to make comics for blind people. It was first when I properly started to work on the project that I discovered how incredibly difficult it can be, how challenging and controversial it can be. Also keep in mind that some people deeply dislike my work—there’s really no common standard for how it’s received. But there are also those who find it important, who feel it pushes boundaries. I never know what kind of reaction I’ll get, even in places with strong critical traditions. Some people find what I do offensive.

At the same time, an academic edited collection devoted to your work has been published. That’s a rare honor—usually reserved for much older or more well-known artists.

Yes, you’re right. These collections are usually about people like Art Spiegelman or Marjane Satrapi—in other words, people who sell books and are household names, which I’m not. I obviously welcome the collection—it shows that comics studies don’t have to be obsessed with celebrity. I think it’s important for the field to disengage from commercial success and really consider what artists have to say. The equivalent in film studies would be to only publish books on blockbuster directors—I couldn’t think of a more boring topic.

The book in question, Ilan Manouach in Review, will also be published in French, as requested by some readers in Belgium. Pedro Moura, the editor, is working on an expanded version right now.

Congratulations.

Well, it’s not really thanks to me—it’s all Pedro. I find it very courageous of him to take this on.

We also need to address your interest in AI as a tool for comic production. Your article in The Comics Journal, “In Defense of Synthetic Comics,” as previously mentioned, caused quite a stir. I assume you anticipated the emotional reactions it would provoke. For instance, in Sweden, the artists’ union Swedish Artists recently issued a call to action after reporting that one in three of their members had lost work due to AI. The situation is particularly dire for cartoonists and illustrators, who face a double blow: on the one hand, shrinking markets for commissioned freelance work; on the other, the unauthorized use of their artwork as training data for generative AI systems. How do you view this development?

Well, for me, the question is a bit different. I come from a place where there were no jobs for comics artists. This had already occurred. When comics artists say that they will lose their jobs because of AI, they say it because they feel deluded. There’s no place where a comics artist can earn a living making comics.

Sorry to interrupt you, but in this case the union is predominately referring to other paid gigs—for example, illustration work—which is the way many cartoonists pay the bills. Their work has gradually been replaced by AI images because it’s cheaper and faster.

Okay. I don’t know. This isn’t really my field, as illustration and comics are two separate things. However, I must say as an artist that if you can be replaced by a machine, your work probably wasn’t that great to begin with. Another element that needs to be acknowledged is that comics artists have never had work, so the problem isn’t AI. The real problem is capitalism. They could create their own AI that helps them with their work. Moreover—and now I’m being a bit mean—I’ve never seen anyone from the comics community who has a problem with posting and liking on Instagram three times a day. Given this, I would take for granted that comics artists are perfectly fine with capitalism. If they are so enthusiastic to use the tools that are proposed to them, having for years shared their lives online on social media platforms without any questions asked about who is losing their jobs to machines until it hits them, I think it’s problematic. We call this NIMI—Not In My Industry—which means that I don’t give a shit if I take an Uber, I don’t care if I buy books on Amazon or listen to music on Spotify. However, when something hits my industry, such as AI in comics, I will be very against it. I don’t buy this. I would only listen to arguments from people who either master these tools, have experience using them, or have consistently refused platforms based on data extraction—which has been the industry standard for over 20 years.

I see it less binary: I am certain that many comics artists are well aware of the problems associated with social media platforms, that they are the content, and that they would have preferred not to publish on platforms owned by Meta or any other major corporation. But they are forced to since it’s one of very few channels available to reach out with your work. Especially since even the larger comics publishers do little to promote the books they publish. In short, it’s a necessary evil.

No, there are no necessary evils. I don’t buy that. Nothing is necessary. People don’t need to go onto Instagram to promote their work. Now, in 2025, it’s more obvious than ever: I can’t think of a more uninspired move than to post about your work on Instagram. Only corporate people are doing it. The great artists are leaving Instagram behind; they don’t need to promote their work anywhere. If their publishers aren’t doing what they are supposed to, then the artists need to find other ways to promote their work, to have it circulate. If we consider this a necessary evil, we should also acknowledge that with necessary evils come necessary consequences. Instagram has been the industry standard for all comics artists and illustrators, but the moment a tool comes that uses my data then I’m protesting in the streets? I find this kind of logic to be juvenile.

What is it specifically with generative AI that appeals to you?

This is a topic that we could speak about for hours. But what I find fascinating with AI is that it does things in innovative ways. I recently read an amazing book by Rick Rubin called The Creative Act in which he mentioned AlphaGo, the computer program that plays the boardgame Go, which was trained on data—not on social etiquettes on how to play the game. The machine probably knew less than the human it won against but it played the game in unexpected ways due to not being limited by expectations about what you’re supposed to do and how you’re supposed to act. I find this really refreshing and it taps into what I appreciate with AI; it allows me to approach comics in a novel way, being slightly alienated by the medium. I also enjoy technical difficulties, how to solve things—for example, how to make a comic for blind people.

Let’s see if that answer wins your critics over.

Probably not. There are so many conspiracy theories floating around in the comics community about me, including me working for Elon Musk, which is absolutely crazy. Another thing that people are saying about me is that it’s a lack of talent that pulls me to AI—that I simply don’t know how to draw, that I am not a real cartoonist. However, I also get more nuanced critique. For example, that a part of comics is to respect the craft, that AI puts craft in danger—something that I don’t agree with since I consider craft to be an evolutionary thing. Another thing about this form of critique is that it often comes from countries with a rich comics history, such as Belgium, the US, Italy, and so on. Never from places like Colombia or Greece. I think that in countries where comics have been around for a long time, people dislike the idea that comics production is now available to anyone, not just for the few talented ones who have the luxury to go to good schools to learn the craft. This is something important to consider: where do people who make comics come from?

You’re arguing that AI offers a form of democratization of comics production?

Yes, for anyone who has the time. Because making comics is not only about generating images, it’s about creating systems between images and text that need to work together. An AI only creates images, which is just one element in the system that makes a comic; it doesn’t create systems.

Another common objection to the use of AI is that it doesn’t create anything novel. With AI, there won’t be a new Tove Jansson, Edward Gorey, or whoever you’d like to throw in the mix.

What is new? I don’t care about what’s new. Do you think that all comics artists are producing something new? I doubt that.

Of course everyone has their own influences, even when they, like Borges suggests, create their own precursors. But that’s still something else than what an AI creates. At least today.

I can’t easily answer this question, but it makes me think of a cartoon by Ad Reinhardt from the 1950s where there’s someone looking at a naturalist painting saying “What do you represent?” and the painting turns back to him and says “What do you represent?”. I don’t know what the measurement is in these discussions.

Final question: do you still occasionally draw with a pen?

Yes, absolutely! I do diagrams for upcoming books, I visualize ideas, I doodle, I copy other comics. Drawing is essential.

The post ‘Comics people generally hate what I do’: The Ilan Manouach Interview appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment