From cold-calling his artistic heroes to running one of Europe’s most eclectic art-book publishers, Jean-Christophe Caurette has built Éditions Caurette on trust, persistence, and a refusal to pulp anything — even a flop. I visited him the middle of nowhere to find out how a collector with a knack for “stalking” turned fandom into a thriving business.

It’s hard to get more rural than this, a small village in northern Alsace surrounded by a patchwork of wheat fields and silent lanes. There’s a bus stop, a few houses with well-tended gardens, and — tucked between them — a modest single-story building that could be mistaken for an agricultural supplier. This is the headquarters of Éditions Caurette, a high-end art book and illustration publisher whose catalogue and client list seem to have been teleported in from some metropolitan creative hub.

Step inside and you’re met by the quiet rustle of paper, the whir of a packing tape dispenser, and the smell of cardboard. Fifteen people work here, a mix of specialists and generalists — one accountant, two in order fulfillment, two in wholesale/logistics, three in communications and marketing, one in sales, one in legal, a project manager, a production designer, a producer, an illustrator — and the CEO, who also happens to be the man whose name is on the door. Today, 70% of the floor space is used for storage, making the place look like an office caught in a slow-moving avalanche of its own products. Books, merchandise, and packing materials jostle for elbow room.

Jean-Christophe Caurette, the man responsible for all this, greets me and leads me out of the back door to show off his latest project: a brand-new loading bay and warehouse. The warehouse is still empty, but only for a week, because soon it will store the Caurette back catalog, plus a generous chunk of his own personal library. “About twenty-five thousand books,” he shrugs, as if we all stash a similar number in our homes.

It’s thirty-three degrees Celsius outside — that’s ninety-one Fahrenheit for the metrically impaired — so we decamp to a converted farmyard restaurant in a nearby village of Hatten for lunch. Caurette orders, barely glancing at the menu; he’s been here before.

I first met Jean-Christophe Caurette in 2009, when I joined Alsace Bande Dessinée — the local fan club that organized Strasbulles, Strasbourg’s now defunct comics festival. I was still new in town, and "J.C." spoke only to me in French, despite being fluent in English, knowing that was the only way I was going to learn French like a native. At the time, he was but a commercial photographer and comics collector.

Caurette speaks French, English, German, and Spanish, crediting early role-playing and computer games for his English. “I remember translating pages of the Dungeon Master’s Guide with a big Harrap’s dictionary,” he says.

In 2007, the east of France was a BD desert in terms of festivals, but that year the members of Alsace Bande Dessinée decided to do something about it, launching the first "edition" of Strasbulles in 2008. The name is of course a neologism borne of the fusion of Strasbourg and bulles. Bulles is French for bubbles, or speech balloons — and also happens to be the very same phonetic name of the village that is home to Editions Caurette – Buhl. Little did I know at the time, but when Strasbulles was born, it was J.C.’s first foray into the professional side of comics.

Well, that is if you don’t include his stalker-like phone calls. It seems J.C. had a habit of calling authors simply to tell them that he was a fan of their work. Considering social media was still in its infancy, I could see how this might have been vaguely acceptable to the people he targeted, but only at a stretch; what was wrong with fan-mail exactly? “I decided that if I really liked someone’s work, I should tell them,” he says. “So I would find a phone number, pick up the phone, and tell the artist I really liked their stuff. Just out of the blue. There was no other intention behind it.”

Long before Strasbulles came into existence, one of those calls went to Éric Hérenguel, creator of the fantasy epic Edward John Trelawney that J.C. had just finished reading. Remarkably, far from being creeped-out, Hérenguel was flattered to hear from a satisfied reader and the two soon hit it off. In due course, Hérenguel became a festival guest, friend, and gateway to other contacts. In fact, J.C. reckons that more than half of the artists that he invited to the first Strasbulles in 2008 came, directly or indirectly, because he had already built a relationship with them through, er, phone-stalking. The secret to getting them to say yes? “They told me, if you feed us well and give us somewhere nice to stay, we’re happy,” he says. “So that’s what we did. And it worked.”

The results were remarkable. The festival floor buzzed with the chatter of fans and the scratch of pens signing books in a round table format, while in the back rooms authors swapped stories over a glass of Meteor and a tarte-flambée or two. Strasbulles delivered for the authors and fans from day one, and word spread.

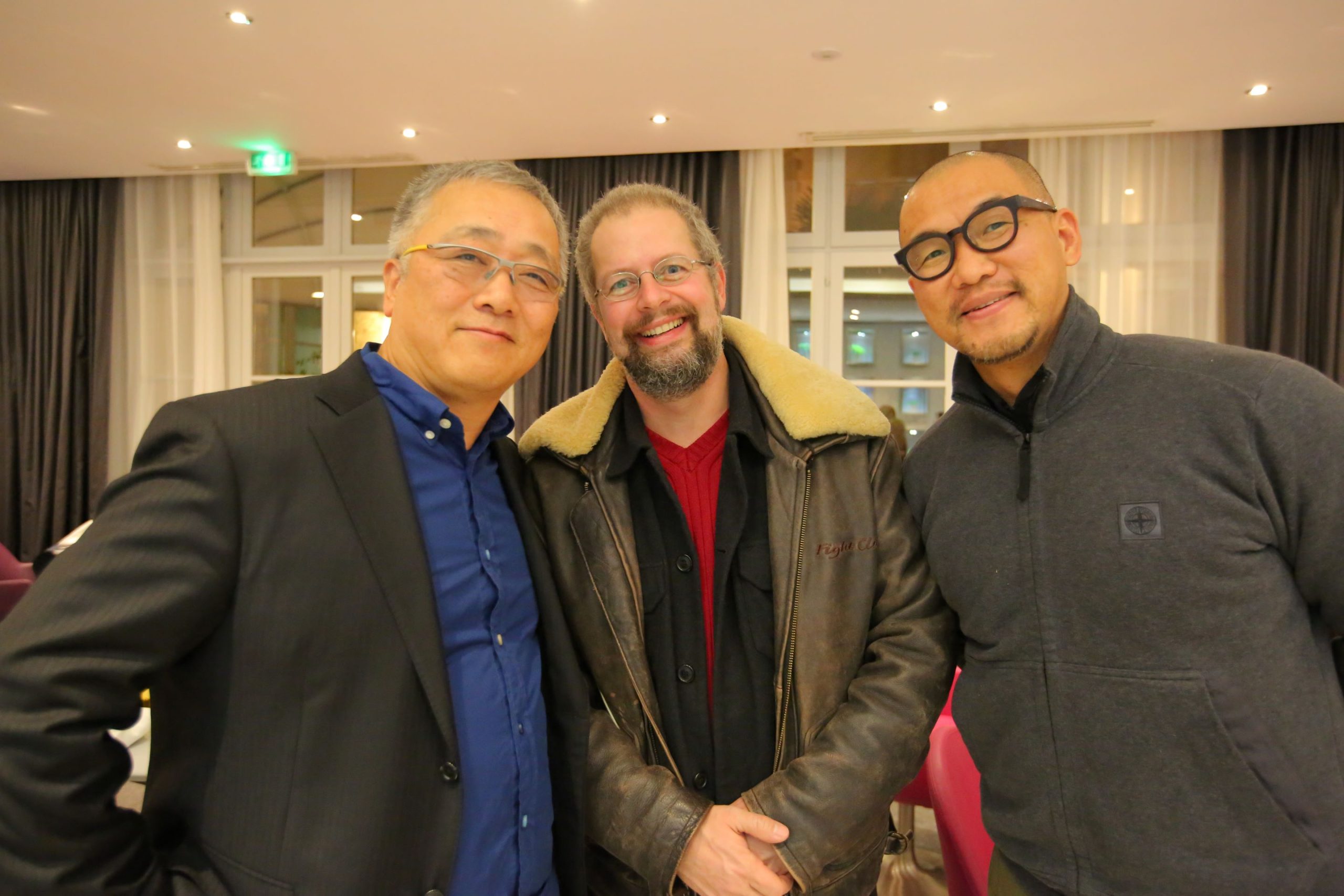

In 2011, Hérenguel introduced Caurette to Jean-David Morvan. Already an accomplished author of countless albums, Morvan had spent years plying his trade in Japan before the Fukushima nuclear disaster forced him back to his native France; JC immediately took this opportunity to invite him to Strasbulles. Soon after meeting, Morvan and Caurette found themselves in Paris with an afternoon to kill. They wandered into the Daniel Maghen gallery near the Louvre and were confronted by a roomful of impossibly large, impossibly detailed ink drawings by a Korean illustrator neither of them had ever heard of. The drawings were vast, intricate, and — astonishingly — done straight to canvas. No pencil, no sketching, not a line out of place. The artist was the singularly talented Kim Jung Gi. His work was alive with humor and detail: street scenes teeming with bizarre figures and surreal beasts woven into impossible perspectives. “I thought, we have to get this guy to Strasbulles,” he recalls; and they did.

Kim attended Strasbulles as the 2012 guest of honor, wowing local audiences with his straight-to-canvas outlines of the surreal and bizarre. Of course, he arrived with suitcases full of his 2007 and 2011 sketchbooks to sell — but with a price tag of around 100€ each – was forced to leave most of them behind, unsold, once the festival was over. “He only sold about ten,” Caurette says. “So, I had another hundred and ninety just sitting there.”

For most people, this would have been a storage nightmare, for Caurette, it was the seed of a business. He built an online store and began selling the books by mail order. The steady sales competed with his photogr

aphy income which proved there was a market for high-end illustration books — if you could find the right audience. The subsequent arrival of Kim’s 2013 and 2015 sketchbooks saw cash flow from book sales dwarf the photography business, and made JC realize publishing might be a viable career.

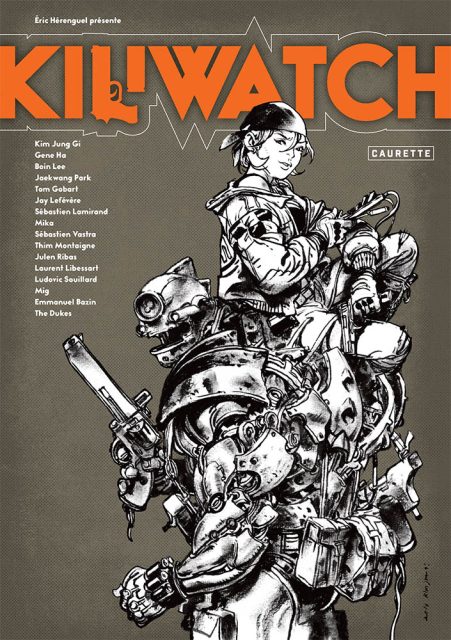

In 2015, he took the plunge, releasing his first comic-book title: Kiliwatch, a Hérenguel-led post-apocalyptic romp involving a gun-toting girl and her incontinent robot sidekick. The book was a blast, but a commercial flop, and Caurette is the first to admit why: “I had no distributor, no idea how distribution worked, and I called bookshops about it the week it came out. Most said, ‘We would have ordered it if we’d known.’”

The book also featured contributions from 14 artists, including Kim Jung Gi and Gene Ha, making the rights situation so complex that J.C. later refused to translate it into English, despite my pleas. “When you have that many contributors, the paperwork is … not fun,” he says. Most of the 3,000 copies that he printed back then will be shifted into the new warehouse. “I can’t throw books away,” he sighs.

We stop by the local “book box” on the way back to the office — a painted wooden closet on a street corner where local people leave unwanted books for neighbors and strangers to take. JC rummages like a man who can smell a rarity through hardwood, emerging triumphantly with three finds. “After I’m dead, my kids might get three euros each for these,” he grins.

Back in Buhl, the new warehouse smells of fresh optimism. The shelving is still bare, a temporary luxury before thousands of kilos of paper arrive to fill it. J.C. sits in the middle of the space like it’s his throne room, this is where the new Kim Jung Gi stock will go, where the Caurette back catalog will live, and — with equal seriousness — where he’ll stash most of his own 25,000-strong personal collection. “I’ve been told I should get rid of things,” he admits, “But I can’t destroy books. I never pulp them. Even Kiliwatch. Especially Kiliwatch.”

By late 2016, the photography business was fading into the background. The accidental success of selling Kim Jung Gi’s sketchbooks online had proven there was both an audience and a business model, if he could scale it. When Morvan pitched him on a 9/11 memorial artbook, Steve McCurry, NYC, 9/11, Caurette agreed and managed to convince Kim Jung Gi illustrate it. This time, he had a distributor — Glénat — and the book sold respectably, which was enough to convince him to go all-in.

Éditions Caurette opened its Buhl offices in 2017. The location made little sense to anyone outside of Alsace — cheap rent and no nearby book trade — but Caurette already had a network that spanned continents, thanks to Kim Jung Gi. Kim’s sketchbooks didn’t just keep the lights on, they became the foundation of the business. “Kim was important for two reasons,” Caurette says. “First, financial. His books were our main source of income for many years. Without them, we couldn’t have started so many other projects. Second, his reputation drew other great artists to us — Karl Kopinski, Jesper Ejsing, Ashley Wood. If you can publish Kim Jung Gi and actually sell the books, people believe you can sell theirs too.”

You have to earn respect, he insists. “Illustration is based on relationships and trust. If you’re Karl Kopinski, you can work with anyone. The trick is convincing him that you’re the best choice.” It’s easy to forget that printing a book is the easy part, “What’s difficult is selling,” he explains. “With tens of thousands of books published every year, you have to find the people who will actually buy them. Kim made that possible.”

When Kim died suddenly in 2022, the impact was personal as well as professional. “We’d been working together for ten years. We’d spent weeks and months on the road together. I really owed Caurette’s existence to him,” he says quietly. In the days after, the warehouse emptied of Kim’s books — including a fresh print run of the 2022 sketchbook — but the success felt hollow. “It was a massive amount of money. And it was very, very depressing.”

Since 2016, Éditions Caurette’s output has been as eclectic as it is ambitious. “Ninety percent of what we do is publishing the books we want to see exist,” he says. “It’s fun and satisfying.” The focus is always on high-quality illustration: art books, children’s books, artist’s editions.

He doesn’t talk about market analysis or bestseller lists, but that doesn’t mean ignoring the bottom line. Very few books make money — “statistically, less than twenty percent,” he says — so the profitable ones carry the rest. The trick, of course, is you never know which is which until after the fact. “We have some books because they make financial sense, others because someone here really likes them. Ideally both. But you can’t only publish safe bets or you’d never make anything interesting.”

For Caurette, a book is never just a stack of printed paper. “A book carries a world inside. It’s part of an artist’s brain made tangible. You’re not buying a kilo of paper — you’re buying a window into someone else’s universe.” This attachment extends to everyone involved. “The artist says, ‘This is my book.’ The graphic designer says, ‘This is my book.’ The printer says, ‘This is our book.’ And of course, the publisher says, ‘This is my book.’ It’s not like a washing machine manual.”

It’s also one of the few industries, he notes, where everyone’s interests align. “In photography, clients want you to work as much as possible for as little as possible. You want the opposite. In books, the author, the publisher, the bookseller — everyone wants to sell as many as possible. In France, book prices are fixed, so we’re not arguing about discounts, we’re talking about the product. You want to sell books? Make books people want to sell.”

And if they don’t sell? There’s always space in the warehouse.

The backbone of Caurette’s catalog is a formidable art book line with luxurious titles by talent from the world of illustration and concept art: Sylvain Despretz, Jesper Ejsing, Bjorn Hurri, Axel Konstad, Karl Kopinski, Raphaël Lacoste, Abigail Larson, Stan Manoukian, and many more besides.

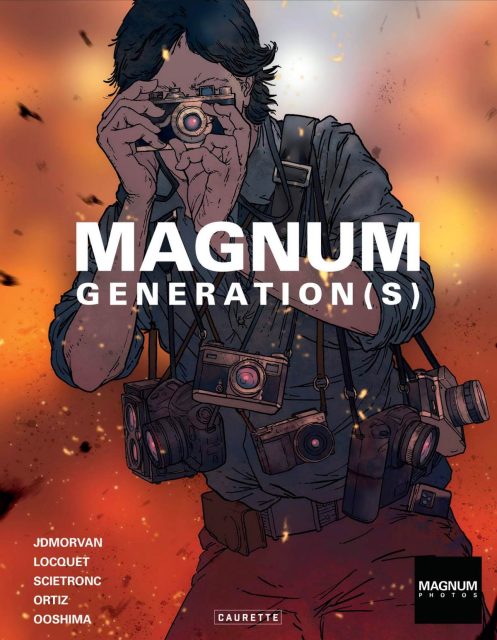

In addition to a line of deluxe French titles, there are a growing number of comic books and artist’s editions available in English: The Kong Crew by Hérenguel, set in a Manhattan where dinosaurs roam free; Magnum Generations, written by Morvan, which tells the story behind the founding of a famous photography agency; children’s classics get a revival in Petzi (a.k.a. Rasmus Klump), newly illustrated by Thierry Capezzone; and the recent two-volume companion to Alex Alice’s Castle in the Stars – The Universe in 1875.

Formats, Caurette insists, adapt to the artist: “Every book should reflect the style and intention of its creator.”

These days, he attends events like Trojan Horse was a Unicorn, Playgrounds in Eindhoven, and Promised Land in Poland, not to scout new projects (“We have too many, some majorly behind schedule.”) but to stay connected. “It’s one thing being stuck in your office all day. Meeting people reminds you why you do it.”

Caurette’s relationship with comics began, like many in France, with Tintin, Asterix, Lucky Luke, and Gaston LaGaffe. However, the title that affected him most as a child was the one meant for older readers that he’d snuck out of his father’s collection: Les Oiseaux du Maître (Birds of the Master) by Pierre Christin and Jean-Claude Mézières, part of the Valerian series. “I must have been seven or eight,” he recalls. “It was very strange, very frightening. Not like Tintin or Asterix, where there are no real bad guys. It left a mark on me.”

When he launched Éditions Caurette, one of his first ideas was to publish an Artist’s Edition of that exact book. So, at the earliest opportunity, he called Mézières for his initial thoughts. “That’s the most stupid idea I’ve heard in a long time,” he told Caurette. “It’s the worst-selling Valerian book.” But Caurette did it anyway. Over time, he befriended both Mézières and Christin. “If I could have told my ten-year-old self that one day I’d be friends with these incredible artists, I’d have been super happy,” he says. “Making books is a way to work with your heroes. Sometimes you’re disappointed, but sometimes it’s wonderful.”

So, what’s next after ticking off the childhood dream list? “To create new dreams for children reading our books today,” he says. It’s a fitting mission for a man who turned cold calls to his favorite artists into a thriving publishing house, who refuses to throw away a book, and who can spot a collectible in a dusty street-corner book box.

In a business where trends burn fast and stockrooms groan, Caurette plays the long game. If a title doesn’t find its audience today, there’s always tomorrow — and now plenty of shelf space.

The post From ‘stalking’ artists to publishing them: An interview with Jean-Christophe Caurette appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment