There’s something in the air, and I’m not sure it’s coal dust. After last year’s Black Coal and Red Bandannas, Haymarket Books have published Trouble! at Coal Creek by Austin Sauerbrei. Sauerbrei is, aside from a comics writer and artist, director of the Tennessee-based Statewide Organizing for Community eMpowerment (SOCM). He wrote in Scalawag that got the idea for the comic after beginning work as an organizer for the Chattanooga Area Central Labor Council. While learning the labor history of Eastern Tennessee, a friend sent him a chapter from Dixie Be Damned on the 1891-1892 Coal Creek War that ended convict leasing in the state.

For those who didn’t pay attention in history class or have the misfortune to live in a state where this is all considered woke indoctrination, here’s a brief summary of convict leasing. After Reconstruction, states throughout the former Confederacy created overly-broad criminal codes targeting freed slaves. Once convicted, prisoners were sent to institutions that even the Tennessee legislature reported were “hell holes of rage, cruelty, despair and vice.” Prisons would “lease” out inmates to labor for private companies. Almost all the convicts leased were Black and the system is often described as “slavery by another name.”

Inmates were paid a pittance. The Birmingham Age-Herald, not a radical muckraker but a conservative newspaper, was obliged to report, “employers of convicts pay so little for their labor that it makes it next to impossible for those who give work to free labor to compete. ... As a result, the price paid for labor is based on the price paid convicts.” Colonel Arthur Colyar, both a powerful Democrat and coal company attorney, calculated “that free laborers would be loath to enter upon strikes” so long as his company “was amply provided with convict labor.”

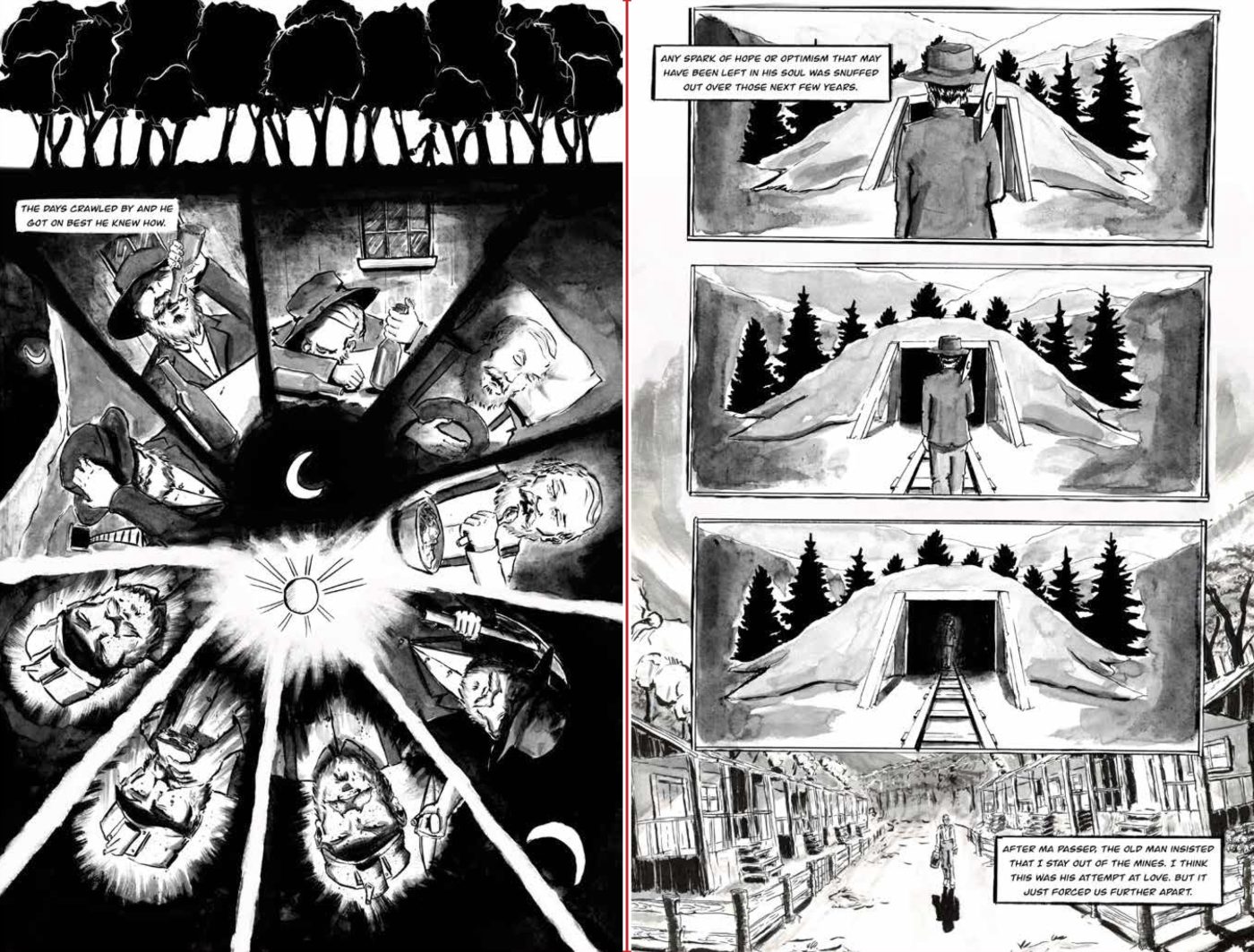

Unlike Black Coal and Red Bandannas, Trouble! is a fictionalization of real events over five chapters starring the son of Welsh immigrants. His mother dies in childbirth along with the baby. The father, a miner, surrenders to despair and drink. Sauerbei gives an impression of the father’s day with a circular splash page showing the cycle of working, drinking, and passing out. Miners in Coal Creek are treated the same as miners in other parts of the country. They’re paid in company scrip, work in unsafe mines, and the coal bosses often lie about how much coal has been hauled in order to make the already-pressed workers work even harder.

Unlike Black Coal and Red Bandannas, Trouble! is a fictionalization of real events over five chapters starring the son of Welsh immigrants. His mother dies in childbirth along with the baby. The father, a miner, surrenders to despair and drink. Sauerbei gives an impression of the father’s day with a circular splash page showing the cycle of working, drinking, and passing out. Miners in Coal Creek are treated the same as miners in other parts of the country. They’re paid in company scrip, work in unsafe mines, and the coal bosses often lie about how much coal has been hauled in order to make the already-pressed workers work even harder.

Shopkeeper Eugene Merell is a rabble-rouser within the community. He gets the townsfolk asking questions about why they are so oppressed and degraded and who is responsible. Merell is also a member of the Knights of Labor. The Knights were an early labor union that preceded the more conservative American Federation of Labor. The Knights accepted workers regardless of race, religion, gender, or skill level. (Well, almost all workers. The Knights vehemently opposed Chinese immigration and supported the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act). The Knights’ slogan was “An injury to one, is the concern of all” a forerunner to the modern labor slogan “An injury to one is an injury to all.”

As if the miners and their families don’t have enough problems, the state begins supplying the mines with convict labors who, as established, will undercut the pay of any free worker. Shortly thereafter, armed miners send the convicts back to Knoxville via train. The governor arrives, bringing with him convict laborers and three companies of the state militia. The invisible hand of the market has called in the mailed fist of the state.

Sauerbrei reproduces contemporary documents that give his story historical authenticity. He includes articles from the Knoxville Journal, fliers, children’s rhymes, and folk songs. The title of the comic is reminiscent of a Journal headline. These help convince any skeptical readers that yes, working people of Tennessee did take up arms in defense of their rights. The state was not always a domain of the American right, and will not necessarily be so in the future.

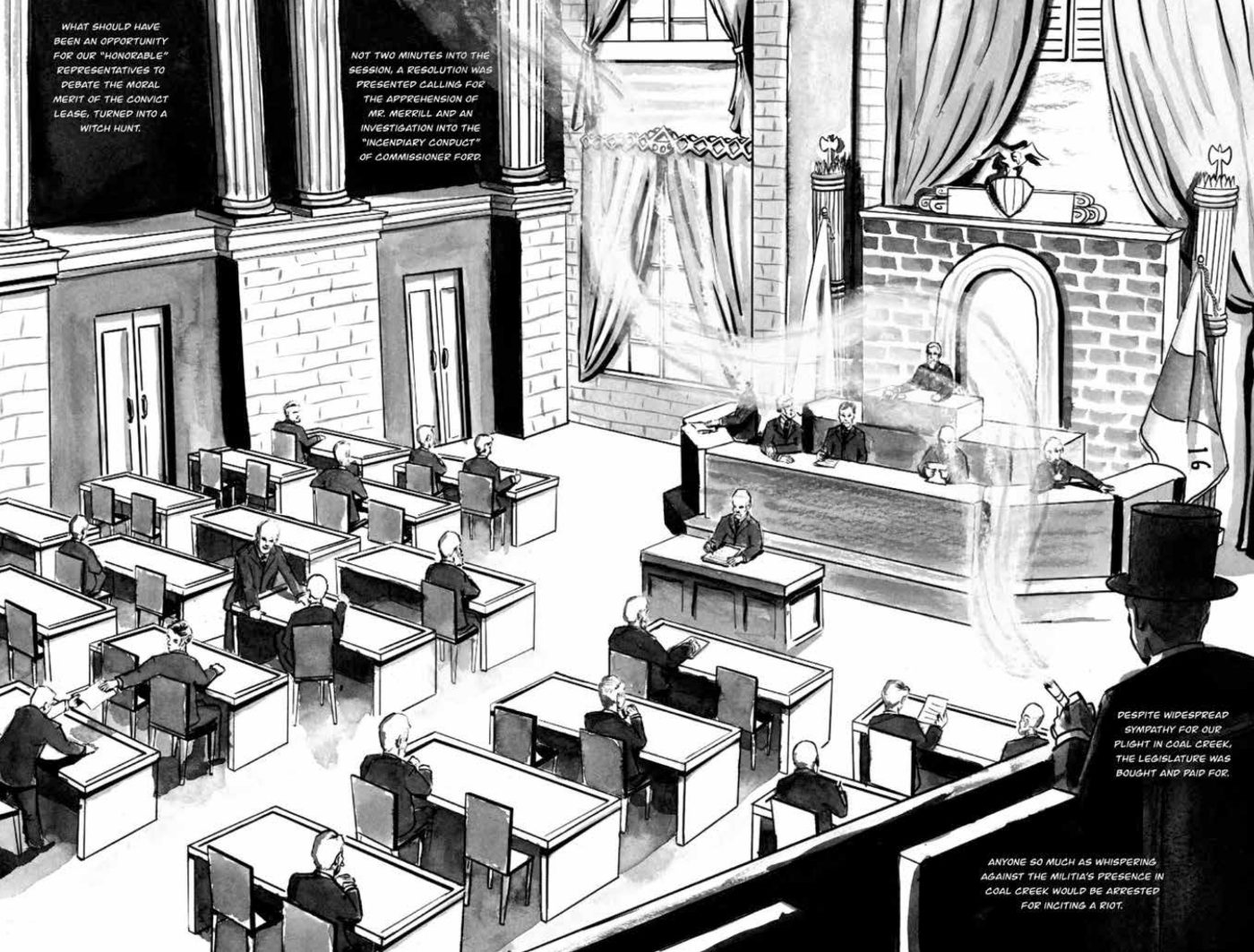

The miners are once again successful at driving off a demoralized militia. Tennessee’s state superintendent of prisons admitted during the war: “Nearly all the citizens of Anderson County around Ethel mines are in sympathy with the mob.” The governor and legislature promise to hear the citizens' complaints. It’s a lie. Sauerbrei draws the chamber overseen by a coal baron with a cigar and top hat. It’s clear who really in charge. Swap out the cigar for a vape and the top hat for a t-shirt and jeans, and he’d be a Silicon Valley tech oligarch of our day.

Chapter 3 introduces a Black character who is a convict lease. His treatment gives one pause. Sauerbrei tells his background in wordless sequences. It seems odd that the only major Black character doesn’t get to speak for much of the chapter showcasing him. On the other hand, his shouted defiance towards a guard stands out all the more because of the preceding quiet.

This is Sauerbrei’s first piece of sequential storytelling. He uses his layouts to create a sense of confinement and oppression felt by miners. More open compositions, such as the destruction of a stockade via dynamite, also have power. His watercolors evoke an eerie mood, particularly a chapter set on Halloweeen night, 1891, showing workers taking a candlelit oath to join the Knights of Labor. His crowd scenes suggest the strength working people can have when united by a common cause.

Trouble! ends somewhat abruptly, before the final battle over convict leasing was won in Tennessee. It’s up to a text afterward to inform readers what happened. Yet, the ending presents readers with an essential choice: to become part of a corrupt system or to work to change it. The protagonist chooses poorly at first, but he’s given another opportunity to put it right. Given the ICE recruitment spree, the choice couldn’t be more relevant for readers.

The post Trouble! At Coal Creek appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment