Twice in her 47 years, Victoria Lomasko lost a country. The first time came in 1991, when the Soviet Union - the nation in which Lomasko had been born and grown into adolescence - collapsed suddenly and irrevocably, along with the Communist world at which it had always stood at the head. Lomasko was born in Serpukhov, Russia (near, but not in, the metropole of Moscow) during the waning years of the Brezhnev era. The daughter of a government propaganda artist, Lomasko came early to an open love of art (studying book design and graphic art at the Moscow State University of Printing Art) and a more surreptitious passion for journalism and political activism.

As the Soviet era gave way to a new and fractured post-Soviet world, Lomasko found a way to draw the two passions together, taking on the role of a graphic journalist whose drawings of a rapidly changing world became a visual chronicle of cultures and memories that were, even then, becoming lost to time. Influenced by the work of the popular 1930’s Russian travel writers Ilf and Petrov, Lomasko began to assemble a series of portraits and accompanying textual pieces, documenting the widespread and formerly hidden cultures of the Soviet periphery, traveling throughout Russia and other former Soviet Republics to document the people she met along the way.

After some two decades of work in her home country – increasingly restricted but never entirely suppressed during the mounting years of Vladimir Putin’s dictatorship – Lomasko’s book Other Russias became her first published in the United States in 2017. A travelogue in pencil sketches throughout Eastern Europe, her book provided a snapshot of a world on the brink of some kind of epochal change; though whether the result would be transnational revolution, or a fall into renewed repression, neither Lomasko nor her subjects quite knew.

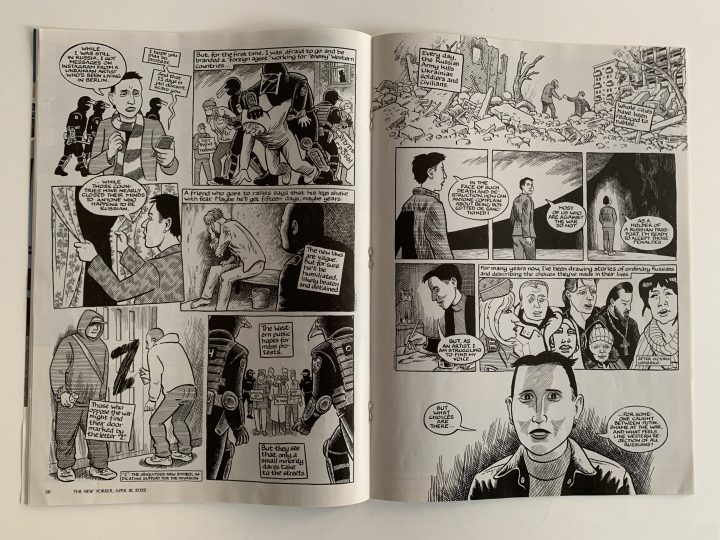

Lomasko’s follow-up, The Last Soviet Artist, began as a series of bulletins about the then-unfolding protests in Russia and Belarus, and the consequent wave of repression and censorship that followed in both countries. It took an unexpected turn in 2022, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine inaugurated the full flowering of Putin’s authoritarian regime: a crackdown on political writers and artists of any kind, which forced Lomasko into her second exile to date as she managed to find a new home in Germany, where she lives today.

The latter portion of her book is a very different beast: the story of an artist trying to find her way in a new and uncertain world that has yet to accept its ties to the one she fled. Along the way, she has become more overtly influenced by the graphic journalists and comics artists of the West: The Last Soviet Artist includes a notable collaboration with Joe Sacco, with whom Lomasko has often been compared. As America itself adjusts to a new life under dictatorship, and as the reality of displaced peoples and lost nations becomes increasingly and urgently universal, Lomasko’s art and journalism are something of a guiding light for the community of artists and graphic journalists across the globe.

This fall, a new documentary film about Lomasko entitled Tree of Violence is under distribution as part of the Draw for Change series of documentaries about international cartoonists. This interview took place in two parts. The firstly in conversation during April, 2025, when Lomasko was briefly in the United States. Because that interview left certain gaps due to differences in language (Lomasko speaks English, but not to her own satisfaction; I, to my frequent chagrin, speak no Russian at all), further additions and amendments took place via email in September.

Zach Rabiroff: You were born near Moscow during the late 1970s. Tell me about what life was like for you when you were growing up.

Vika Lomasko: I was born in the small town of Serpukhov. Life was very modest, I would now say poor, but in my Soviet childhood, I didn't understand that because everyone around me lived the same way. Somewhere in Moscow, there were members of the government, professors, editors of huge magazines, and famous actors, but even with them, the social gap was not huge.

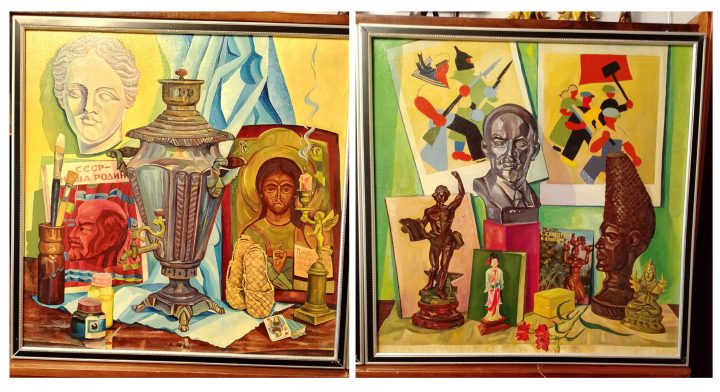

My parents lived in a Khrushchyovka, a standard Soviet building with five floors and small apartments. When I visited my classmates, I saw more or less the same thing: Soviet carpets on the floor and walls, a sideboard with crystal service, a small black-and-white TV, and, of course, a bookcase. My parents' apartment differed because instead of carpets, dad's paintings hung on the walls, there were also paintings under the beds, and books filled all the cabinets and even suitcases.

Sometimes there were crises with certain products, for example, sugar. I remember standing in line with my parents in winter to get sugar with a coupon. It was dark and -22°F, but even kids had to be there in person to get sugar. At the same time, the general mood was one of leisurely calm, because people felt completely secure in basic issues. Everyone received free education and free medical care, it was possible to get free apartments from the state, there was enough work for everyone, and it was possible to live on a pension. Compared to the American middle class, our life resembled poverty, but compared to the American working class, we lived very well. To some extent, a utopian state had been built.

So there was never a sense of insecurity. You never felt like you might be out on the street.

Absolutely. Growing up in the Soviet Union, I knew that people could live on the streets only from books and films about capitalist countries. When my book Other Russia was published in New York in 2017, I spent about two months in America and wrote a short graphic essay called Isn’t America a Dream?, which included the following passage: “You’re supposed to put your credit card in and out, and when, after a fifteenth attempt, I still couldn’t buy the ticket to get on the train, I suddenly felt very lonely. New Yorkers rushed past, each one of them with only themselves to rely on. ‘In Russia, you’re never alone. You’re always controlled. They’ll say something rude to you, scold you, but in the end, they will push you through,’ I thought, standing before the metal door that refused to turn for me. ‘What if control is also a form of care?’

While you were growing up, your father was a propaganda artist for the government, is that right? Tell me about that. What sort of art was he doing for them?

He worked in a large secret factory as an artist decorator in a team of other artists. These artists collectively created monumental propaganda on the facades of buildings, painted the interiors of factories, and decorated Soviet celebrations, such as November 7th, the day of the Great October Revolution, or Labor Day. My dad also constantly drew posters. He was not a communist and hated drawing propaganda, but he didn’t find other work in our small town. For himself, he drew Serpukhov landscapes and even some things with a hint of criticism of the power.

I couldn't visit the secret factory where my father worked, but I often visited the printing house where my mother worked. The printing house, like all other enterprises, also had its own artist-decorator, and he painted rooms with landscapes of birch groves. I think that's nice. As you know, I don't only do graphic books, but also monumental murals and panels; moreover, this is my main passion. I just finished a monumental panel for a cultural centre in the Netherlands, and I dream of painting libraries, canteens, schools, enterprises, and so on. I believe that such monumental murals are an invitation to the audience for dialogue.

Almost like a religious calendar except for the Communist political calendar.

There were years when Labour Day and Orthodox Easter fell on the same day. I remember a demonstration on Labour Day—cars decorated for the celebration, crowds with red flags. My parents were bored, but I was happy that something was happening and waved my little flag and red balloon. After the demonstration, we immediately went to my grandmother's private house, where she had prepared Easter cakes and painted eggs. I rolled Easter eggs with the same pleasure as I had just waved my flag.

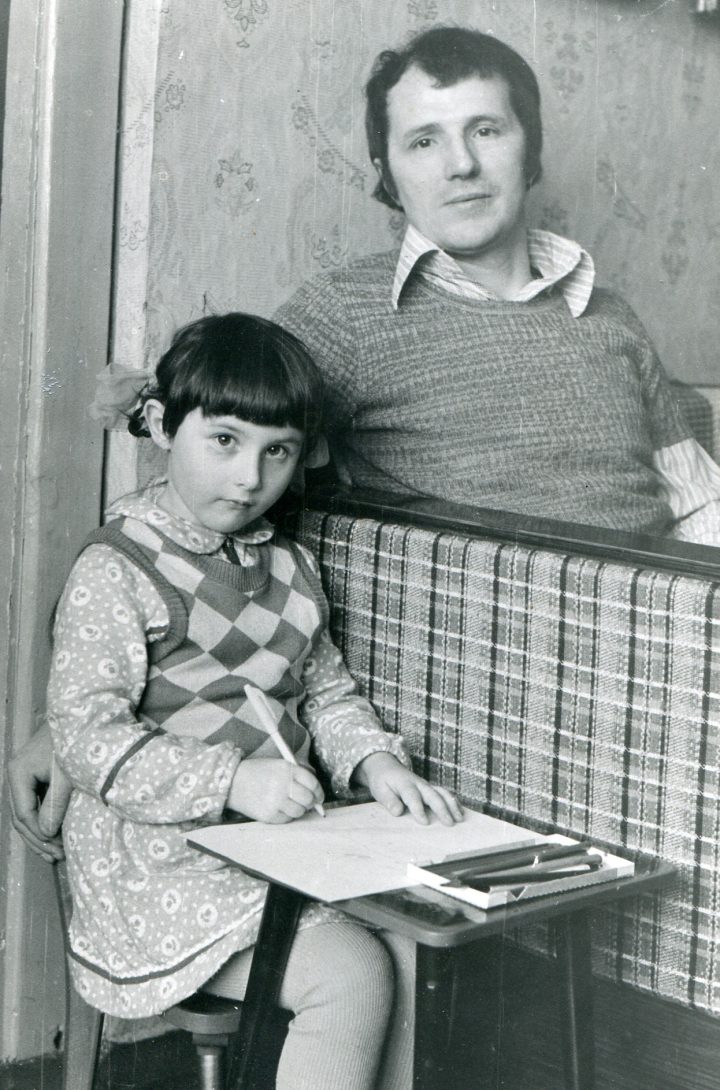

So did your father's art have any influence on you, do you think, as you were becoming an artist?

Even before I was born, without knowing the child's gender, he bought art books to raise an artist. He didn't care whether it was a boy or a girl; he believed it would be a great artist. When I was three years old, my dad primed some canvases for me with lilac paint. They were bigger than me, and he suggested I try painting with oils. I have never really loved painting with oil paints, but I enjoyed creating stories and illustrating them.

My father isn't an easy person, and his idea of making his child an artist from birth could sound like abuse. But for me, the main thing is his devotion to art, his belief that life without art is not even worth living. It's something very Soviet, from our utopian state with its ideas of art for the proletariat. I perceive my path not as dependence on my father, but as a joint service to art—I am developing what he was unable to realize.

Who else do you think influenced you as you were starting to develop your own early style?

As I said, some of our books were kept in suitcases. I had my own suitcase filled with children's picture books. I didn't just look at them, I researched different styles and memorised the names of my favourite illustrators. I preferred the illustrations by Oleg Vasilyev and Erik Bulatov, who worked as a pair, as well as Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov. When I entered the Moscow State University of Printing Arts and moved to the capital, I discovered that my favourite illustrators were actually the most famous Russian conceptual artists—during the Soviet era, they earned a living from illustration, but created art for themselves, which they only showed to friends. After the collapse of the USSR, they became famous conceptual artists. In my childhood, I was influenced by their style of illustration, because they are all unsurpassed masters of complex multi-figure compositions, and as an adult, I was influenced by their books about art. I still remember a quote by Oleg Vasilyev: “For me, the objects I create—paintings, drawings, and so on—are not an aim in themselves and are not the essence of my working process...The point is that my work forms me. I live this life and create myself.”

This is the stage I am going through—from an illustrator and artist-decorator to a visionary artist.

So at what point did you start to develop an interest in politics? Did that come from an early age or was it later on?

As a child, I believed that what my father drew at the secret factory was political art.

As an adult, I realised that art illustrating the current political agenda and events must be clearly separated from art that independently explores reality to suggest new perspectives and forms on this basis.

So it was really something you had to discover on your own.

I started with drawing vulnerable social groups, and in 2012, I transitioned to drawing reportages about the Moscow protests, which seemed to me like a great historical event. Now I realise that I was working as an activist artist who was illustrating the political agenda. Actually, there is not much difference between an “activist artist” and a “Soviet artist-decorator.” Both follow the current political situation rather than shape it.

You were young when the Soviet Union came to an end. What was your reaction to it at the time, as you were coming out of school or still in school and thinking of becoming an artist? How did you think things were going to change?

People were informed on television that the USSR had collapsed. Perhaps there were some public discussions in Moscow, but in the provinces, people just watched the news and had no idea what to expect. I was a teenager and was as happy as my peers—now we had jeans, Fanta, Snickers, and other previously unavailable items from the Western world. We happily left our Soviet past, not realising that we left not only ideological control but also our leisurely pace, stability, equality, and economic security.

So, it sounds like even then there wasn't really a sense of optimism or a sense that things were going to be much better. It was mostly uncertainty and instability.

Factories were closing one after another, and people were losing their jobs. There were shootouts in the streets. Once, bandits broke into our apartment, and my father waited for them with an axe in his hand. Many of my peers tried drugs for the first time, and some died from them. I can compare Soviet people to plants that lived in their own environment, but suddenly global changes happened, like a field turning into a dense forest. Not everyone was able to adapt and survive.

At that point you were becoming an active artist for the first time, and much of your work then and later on was about exploring Russian cultures outside of Moscow. Where did that originally come from? What made you want to explore that?

Because I'm from a provincial town. Were you born in New York?

Not born here, no.

I have been to America many times and found similarities between our countries. The main similarity is that both New York City and Moscow are like separate states within states, and we believe that all the most interesting things happen only there. I can't imagine someone, for example, coming from Ohio to New York to talk on stage about the lives of ordinary people in their state. After the collapse of the USSR, stories about life in the provinces, which were usual before, disappeared. Artists began to follow the conceptual and abstract trends in Western art, attempting to create something similar.

In the edition I have of your first book, Other Russias, the book is divided into two sections. The first section is called "Invisible". It sounds to me like you’re echoing that here, when you say that these cultures were truly becoming invisible to the mainstream of Russian society.

I think there are plenty of “invisible” stories everywhere. For example, I now live in Germany, where there is still a gap between the western and eastern parts, the former GDR. I see that it is much easier to get a grant to study African countries than to study the lives of people in provincial towns and villages in East Germany. My friend, a sociologist, worked in the UK and was unable to find a grant there for her research on the life of the British proletariat. Travelling around cities to draw workers, peasants, and teachers was a practice of Soviet artists in the 1920s, which was unfortunately later spoiled by censorship and propaganda.

So did you find in exploring these other regions and these other cultures that it was giving you more of an honest perspective on the culture that you were coming from as well?

Before I started doing graphic reportages in 2008, I didn't clearly understand what kind of country I lived in, who surrounded me, what people thought about and my own role.

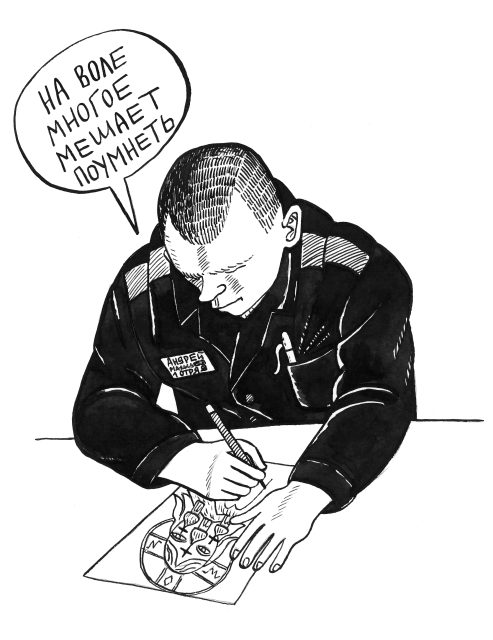

Around this same time, you also started doing work with incarcerated prisoners. How did that begin?

One day, the independent human rights organisation The Centre for Prison Reform asked me to give a free lesson at a juvenile prison. They invited interesting people from different professional fields who could “bring a piece of freedom” for these teenagers. I hoped to use the lesson as an opportunity to draw a graphic reportage from a restricted place. However, my first lesson evoked such enthusiasm among the inmates that I returned, and then, again and again, gradually getting drawn into the role of a teacher. My first education was as an art teacher. So, I remembered how to prepare seminars and created an experimental program for people with any level of drawing ability. Funny that some of the tasks were so good that I still use them in my workshops at the best universities in Europe.

What did you find was happening as you taught these students?

For five years, I regularly visited juvenile prisons for boys in Mozhaisk and for girls in Novy Oskol. We worked on composition, portrait, comic, drawing plein air, and even abstraction. The Center for Prison Reform published three calendars with our drawings and a set of postcards. We participated in several major festivals, an exhibition of contemporary drawing at the Russian Museum, and a collective exhibition at the Reina Sofia Museum, to whose collection I later donated our archive.

Are you still in touch with any of the students that you taught now?

No. If one of them truly decided to become an artist and was interested in keeping in touch, I wouldn't refuse. But in all other cases, it's an extra burden for me. I'm not an activist artist.

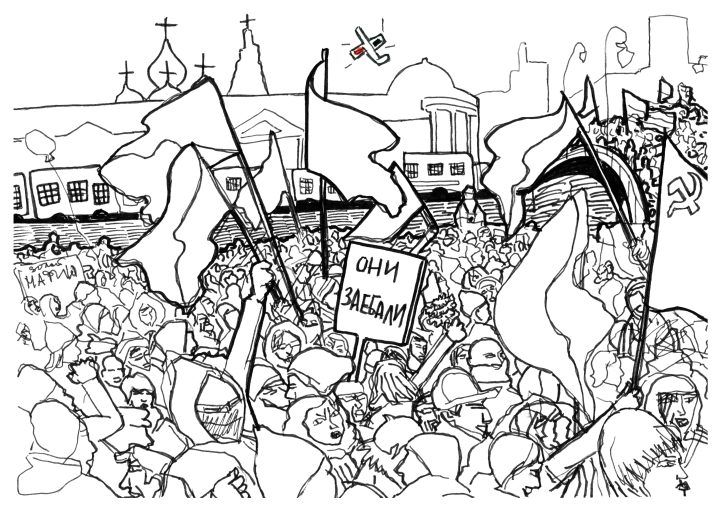

The second section of Other Russias has the title, "Anger,” and it has a very different tone as it starts to document the growth and the results of protests in Russia starting around 2012. For readers here who may not know the context of that, can you talk a little bit about what was happening in Russia during that time?

It started with protests against the government elections, and then turned into protests against Putin. Part of society, liberals and leftists, didn't want him to run for president again.

What happened as the protest started to expand?

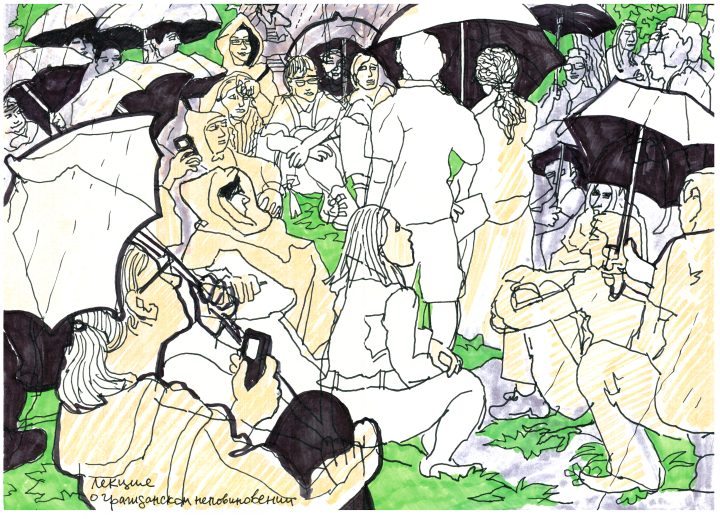

It was very interesting to see different parts of society, such as the queer and nationalist columns, participating in the same rally simultaneously. I mostly remember Occupy Abay Camp, which existed in the centre of Moscow for about ten days—there were public lectures, theatre performances, and my first and, so far, last solo exhibition in Russia. My sketches of camp life were displayed on easels right on the street, and many viewers recognised themselves in the drawings.

At those protests, did it feel like there was a sense of optimism like things might change for the better?

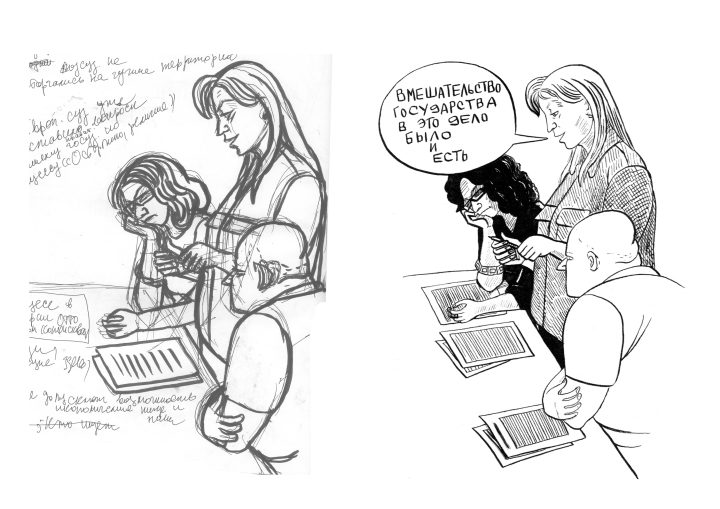

Different groups in society were engaged in dialogue, we were getting to know each other, talking about the future, and feeling inspired. However, it was impossible to open any dialogue between us and the government. Repression soon began. People lost their jobs, some were arrested, and some were expelled from universities. Many of the magazines with which I collaborated were either shut down or had their chief editors changed. Then I found that due to censorship, I could not exhibit or publish my works in Russia.

I also see during that era that your style of art seemed to be changing. The earlier sections of the book have quite simple but realistic-looking portraiture. And then as you get into documenting the protest, it becomes much more stylized or even expressionistic. Was that a conscious decision?

At first, I focused on the style of satirical graphics, for example, works by Herluf Bidstrup, who was very popular in the USSR. I drew with a pen and a marker at the spot of events, and then redrew it at home with ink. Then I grew tired of redrawing and started doing completed drawings on site, using an isograph. I began researching documentary drawings, which were made in 1917, during the Great October Revolution. In 2012, when the Moscow protests started, my new speed of drawing was really useful. I like to capture the energy of events, and I love the rhythm of lines. I also like that my drawings are not just images, but artifacts.

The Last Soviet Artist undergoes a major shift about halfway through the English edition,with the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. What did you originally imagine that book was going to be?

Initially, I wanted to visit all the former Soviet republics and describe The Post-Soviet Space. To understand if the term “Post-Soviet” is still relevant, and if so, why. To document the disappearing cultural ties between our countries and the fading Soviet heritage. What is replacing it and why? I visited Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Georgia, as well as Dagestan and Ingushetia, which are republics that are part of Russia. These trips are included in the first part of the book, titled Traces of Empire. Even during my first trips, it became clear that a visible generational conflict exists in the post-Soviet space.

Describe that to me. What are the differences between those generations?

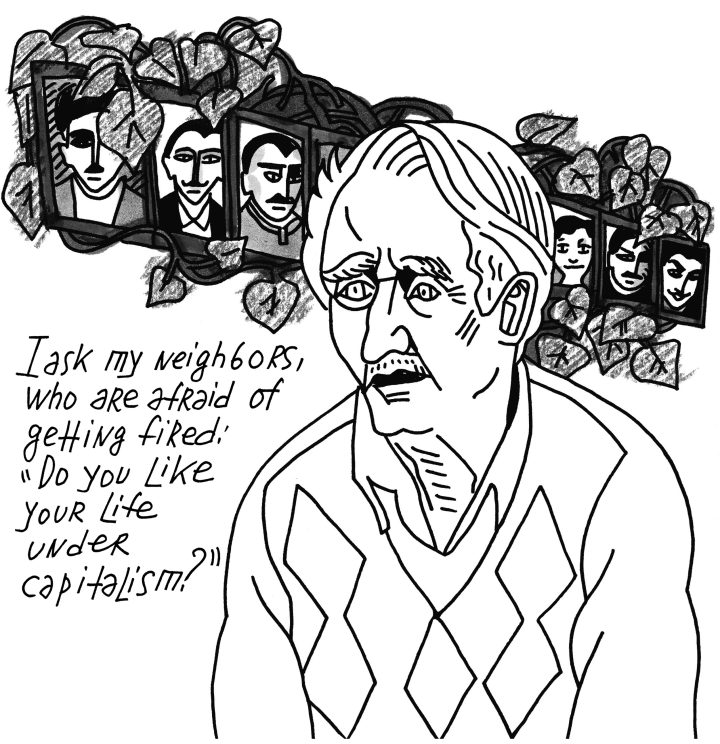

I have already used the metaphor of plants and sudden changes in their environment. Most people who grew up in the USSR remained Soviet to the core. For example, my father couldn’t adapt to the new reality—after losing his job as an artist-decorator, he was unable to find another one. I often met elderly taxi drivers and security guards who were former engineers. These people recalled their past—huge factories, collective farms, city construction—and behind all, a grand image of collective construction of the future appeared.

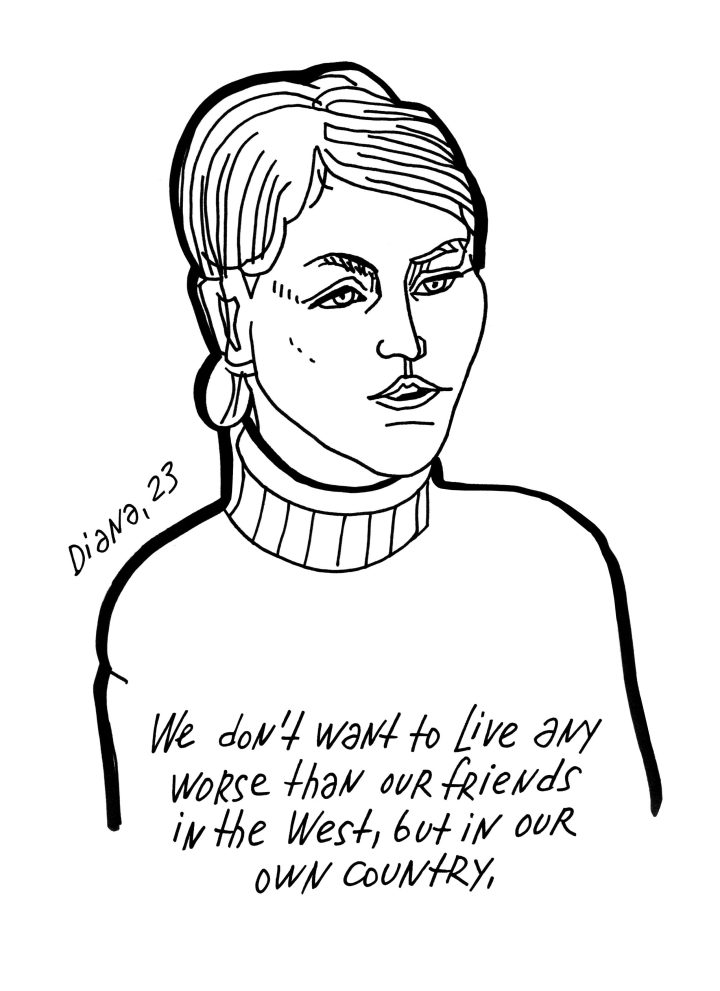

Young people looked to the West. Often, it was accompanied by a lack of respect for the experiences of previous generations.

And what about you? What did you think?

As a person born in the USSR but who was formed after its collapse, I understand both sides. I also used to worship the West like these young people, and at times, I felt a strong nostalgia for the USSR like the old generations. I remember ideological control and pressure even at school. I remember the security and simplicity that I have never found anywhere else. I saw the memorials of repression. I saw the beautiful Palaces of Culture, encircled by sparkling mosaics. Now, I see no other way but to accept both the good and the bad.

Was that true in places like Belarus as well, or was there a different perspective in the former Soviet countries?

In Belarus, I mostly talked with young people who participated in the Belarusian revolution. When I asked how Belarus should seem in the future, they replied, “Like Europe.” Their peers in Russia and Georgia gave the same answer about the future of their countries. Honestly, before living in Europe, I answered the same. Now, after three years of living in Germany, I understand that it’s not so easy to adopt the European system in the Post-Soviet space.

When the invasion of Ukraine started, what changed?

Everything changed for me because mass arrests began on that same day, and it became clear that the totalitarian regime had turned into a dictatorship. I left Russia after 10 days of the war and have never returned.

Was it the war that led to a real dictatorship, or was it a dictatorship that led to the war?

I suppose that both were part of Putin's plans as a complex. The war made the dictatorship visible and unshakeable. Before the war, only opposition politicians, journalists, activists, and political artists became political prisoners. Each such trial was a special event, with rallies organised and media coverage. Now there are many criminal cases against ordinary people who said something extra on their social networks or in their daily lives.

So what did that mean for your ability to survive? What did it mean for your life as an artist?

These historical changes forced me to leave with just one suitcase and my cat and start my life from zero in a new place. For the first year, I moved between countries and cities, not knowing where I could get a long-term visa and settle down. \I was quickly improving my English to start working in this language. However, the most important thing was the search for new subjects and a new visual language. All these movie-like trials transformed me from a graphic journalist into a symbolic artist.

In a way, it feels a part of the global hostility toward immigrants and refugees that we see happening across the globe. Since you are in many ways a victim of it, do you have any sense of why this is happening on such a worldwide scale?

I think it’s global politics to divide people into nationalities which are closed in their countries and hate their neighbours. Much easier to control us.

What can we as individuals, or as a community of artists across borders, do for each other?

Some people in the West are frozen at my public talks – it is so unthinkable for them that I calmly talk about my post-Soviet identity and views that differ from the Western media agenda. The choices are limited: endless struggle with others or acceptance. Accepting others, we awaken in them a sense of dignity and spirit of dialogue.

When I heard you speak in New York earlier this year, somebody asked you what lesson you might have for Americans as we started to live under our own dictatorship. And what you said was very interesting to me. You said, “Get rid of the idea of collective guilt.” And I wonder if you can talk a little bit more about what you meant by that.

Any psychologist will tell you that you cannot help a person if you don’t first free them from guilt, one of the most destructive and debilitating feelings. You know, there is a table of emotions ranging from positive to negative, and in this table, “guilt” ranks below “grief.” After ‘guilt’ comes “shame,” and then the destruction of mental and physical health begins. I witnessed how hundreds of artists and writers who believed in the manipulative idea of “collective guilt” proposed by the Western media were unable to create anything for a couple of years. There were also suicides, especially among young activists.

Dictatorship and/or war are enormous challenges; the time to cultivate a sense of dignity to stand firmly, creating a new vision for the future. Why did Putin win? Why did Trump win? Because we just used the ideas and tools of previous generations without offering any new inspiring ideas. What is democracy in the 21st century? What is its central symbol?

As an exile now in Germany, how have you found it affecting your work?

I think I have already found a new language in my monumental works. It's more difficult with the new book because I have to collect material in English. Since I am in a new society and don't know German, it is impossible to pretend to any objective journalistic research. Finally, I decided that it was okay—I will be the main character of the new book and tell the story from my perspective.

Are you working on any new projects now?

I have been working on the style of the new book, making sketches for new murals, and developing my teaching program. My ideal of an artist is a monumentalist, author of many books, teacher, visionary, and public figure.

My last question for you is, what is the role of an artist in times of authoritarianism, times of repression, times of restriction. What is our role as artists now?

It depends on which artists we are talking about. Commercial artists can continue to work as before and, if they are talented, create interesting abstract paintings or wonderful children's illustrations. It is boring for me to talk about activist artists because they are only familiar with the old idea of “resistance.” I think your question is about artists who are visionaries. To influence the world is possible only with new ideas, and those ideas must be so inspiring that they captivate even our opponents.

The post Vika Lomasko, at home in exile: the last Soviet artist speaks to a post-American world appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment