Comics biographies, by which I mean both ‘biographies of comics people’ and ‘biographies made in the medium of comics, are a rather mixed bag. Sadly, the bag is usually an even mix of ‘boring’ and ‘bad.’ In the comics field the stand-out is probably Billie Holliday by Carlos Sampayo and José Muñoz1. In the realm of the written-word we can probably nominate True Beliver by Josephine Riesman. Otherwise, it’s a pretty barren landscape. Take, for example, A Spirited Life a biography of one, Will Eisner, which is rather successful at stringing facts along (at, least Will Eisner’s version of the facts) but has absolutely zero poetry at its soul. Reading that book, you learn a good deal about Will Eisner’s financial success and his historical ‘significance,’ but very little about the nature of his work, and the odd road a former pulp kingpin took to become “The Father of the Graphic Novel.”

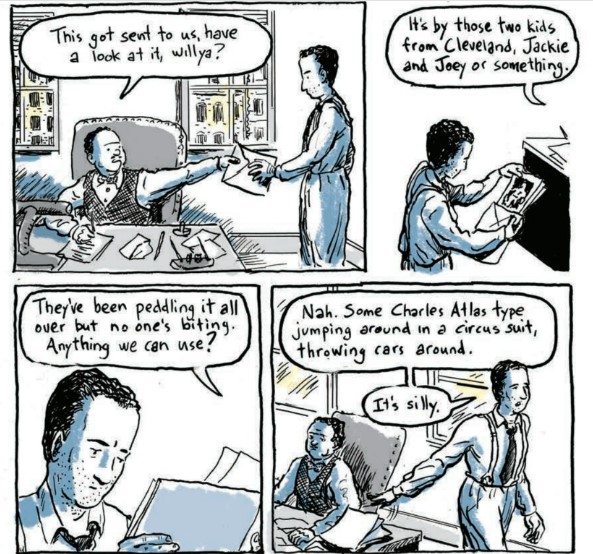

Eisner’s own version of events, the fictionalized biographical comics The Dreamer 2offers even less help. Painting its author in a saintly light, its version of the Wonder Man lawsuit appears divorced from the actual course of events, as a man fighting against the establishment in the name of art; The Dreamer’s main virtue is its brevity. All of which means, the field is wide-open for a good biography of Will Eisner. Whatever you think of the man’s actual talent, as his reputation took several critical dings in the 21st century with new generations no longer accepting his greatness as a given, his presence in so turning points of comics history establishes him as a vital figure. Existing at the crossroads of the comics strip, the comic-book, the rising alternative scene and the dawn of the graphic novel3

Thus, this new work by writer Stephen Weiner and artist Dan Mazur, released through NBM (they have a lot of comics biographies out, I assume it’s a good niche for the library market at least). I would characterize this as a book of two parts – the first of which mostly works, while the other is as dull and listless as A Spirited Life. The search for a great Will Eisner biography, alas, must continue. First, the good bits: after an introduction to Eisner family tree, done via that old chestnut of the immigrant boat arriving at the Statue of Liberty, the story kicks off with a presentation of young Eisner and his family moving to a new home in the middle of the night, because they can’t afford to pay the rent.

The first two-thirds of Will Eisner: A Comics Biography exist in the shadow of this early scene. Weiner and Mazur don’t let you forget that Eisner grew up poor and marginalized, even before the great depression hit. The rest of his career, the constant search for financial success that made A Spirited Life into little more than a catalogue of deals, is recontextualized as a boy forever escaping the possibility of failure. Because failure isn’t a critical beating or a book being cancelled early, failure is your family on the street. Much of the rest of Will Eisner isn’t about its protagonist becoming an artistic genius, it’s about him clawing at success however and whenever he can. Eisner’s story is now seen as obvious victory, high-sales, higher critical appraisal (for a while), a legacy assured in the form of a prestigious4 award named after him, but that boy in 1920’s New York couldn’t see this end. Couldn’t dream of it. He could only see the current day, the mountains of work needed just to make it through.

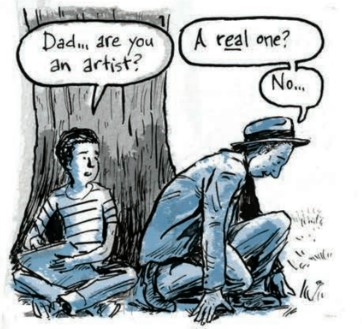

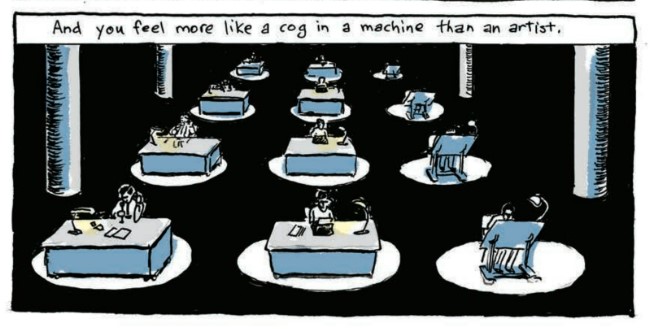

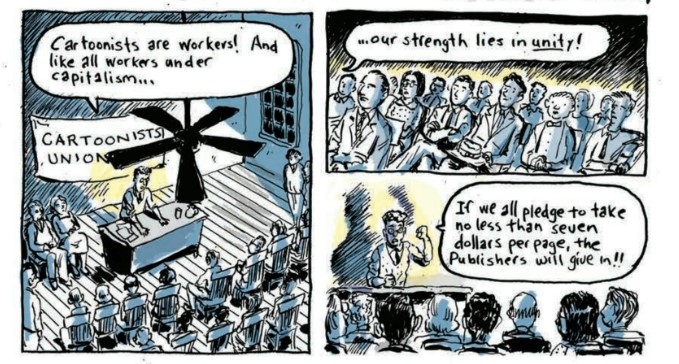

Two pivotal scenes, possibly the best bits, from The Dreamer are reproduced here: In the first Eisner joins a meeting of cartoonists discussing the possibility of a union, but walks out because he cannot conceive of waiting for a better world – he needs to make money now!5; in another Eisner gets his first gig with Jerry Iger not via his artistic talent but through his ability to fix a broken printing-press. He is, nearly literally, a cog in the comics machine. Just as valuable as a reproductive tool – nothing more and nothing less. Walter Benjamin would be proud.

The fact of the matter is that Eisner’s eventual success is not the kind that you build stories around. He didn’t succeed because he was ‘good’ in terms of art. He succeeded because he needed to do so to keep his family in the black. Because he was willing to grind day and night. Because, despite his protestations, he accepted Iger’s logic that comics-making is just a sausage factory. While comics-work is presented throughout this first part of the story, and much is made of Eisner’s ability to work across varied genres, the authors don’t pretend Sheena or Hawks of the Seas are lost masterpieces. For as long as it remains a story of man inside the industry wheel, Will Eisner: a comics Biography is surprisingly focused and good. Once it sheds these elements, once it adopts the more glorifying attitude of The Dreamer, the book quickly looses its charms.

The last third of the book crams a lot in. And I mean a lot. The creation of The Spirit, the World War II period, the marriage, the retreat from active comics making, the first introduction to the alternative scene and (finally) the creation of A Contract With God. That last bit remind of a visit in The Louvre: from the moment you step inside, sign after sign guides you in the direction of the Mona Lisa. Surrounded by hundreds of thousands of masterworks, the audience is guided through as if nothing else matters. My family rushed by works that could be appreciated for hours until finally reaching a rather small painting. What we saw was (mostly) the rest of the audience crowding around it. Here is A Contract with God within Will Eisner: A Comics Biography. Hugely significant, as if the whole work was building-up to its appearance, and the same time so small and disappointing.

It's there because it ‘needs’ to be there. Because it's one of the few works everyone knows. It's there for the same reason several scenes in Eisner-Iger company highlight the presence of the future Jack Kirby and Bob Kane. As if the book is poking you in the ribs and asking ‘did ya get it? did ya?’ Likewise the scene featuring a young Art Spiegelman in the background, with a Maus mask – just to make sure we understand. It’s the laziest sort of biography, the one that highlights that which was already highlighted. Will Eisner: A Comics Biography gives the audience what it wants instead of what it needs. A good biography isn’t just the sum facts of a person’s life. It is a look upon their place in the world, their influences and impact. Their place in a society.

The fact of the matter is that in 2025 I no longer accept as a given that Contract With God is a masterpiece, and suspect I am not the only one. A recent read-through of Eisner’s more significant works as a graphic novelist (the stuff published in the three large hardcovers by W. W. Norton & Company) shows a men as inadequate with typewriter as he able with a pen and pencil. Will Eisner, the writer, does not rise to the level of Will Eisner, the artist. Presented for years as comics’ own Philip Roth or Saul Bellow, what I saw was mostly second-rate Yiddishkeit, filled to the brim with one cliché after another. None of these figures had inner selves – their melodramatic outbursts perfectly equal their empty selves; like actors on the stage hamming it up for the back rows because they know the script sucks. The sort of stuff Matan Hermoni was satirizing in his novel Hebrew Publishing Company.

While I am willing to accept that someone else would look at that work and call it ‘genius,’ certainly many people have, but I am not willing to accept the laziness of just assuming that it is. Instead, after 200 balanced pages Will Eisner: A graphic Biography falls into the same faults as the work of his subject – mistaking largeness of expression for largeness of quality. Maybe it is, then, a fitting tribute to the work of Will Eisner. Trying to capture the man at his best it shows him not as the auteur he always believed he was, but forever a boy struggling for validation – by his parents, his peers, his audience. A dreamer, for sure, but one whose dreams are far less noble than he wishes to believe.

Other parts of Eisner later history, more sordid parts, are glossed-over. The response to the racial caricature that was Ebony in The Spirit is limited to two pages (the second page being a postscript). The coverage of the Wonder Man case does present Eisner lying on the stand, as opposed to previous biographies, but makes sure to focus on the guilt that eats him inside. In the end, Will Eisner: A Comics Biography, loves its subject a too much to be truly honest with him. A true genius could afford to take a harsher beating. After all, it didn’t stop The Spirit.

The post Will Eisner: A Comics Biography appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment