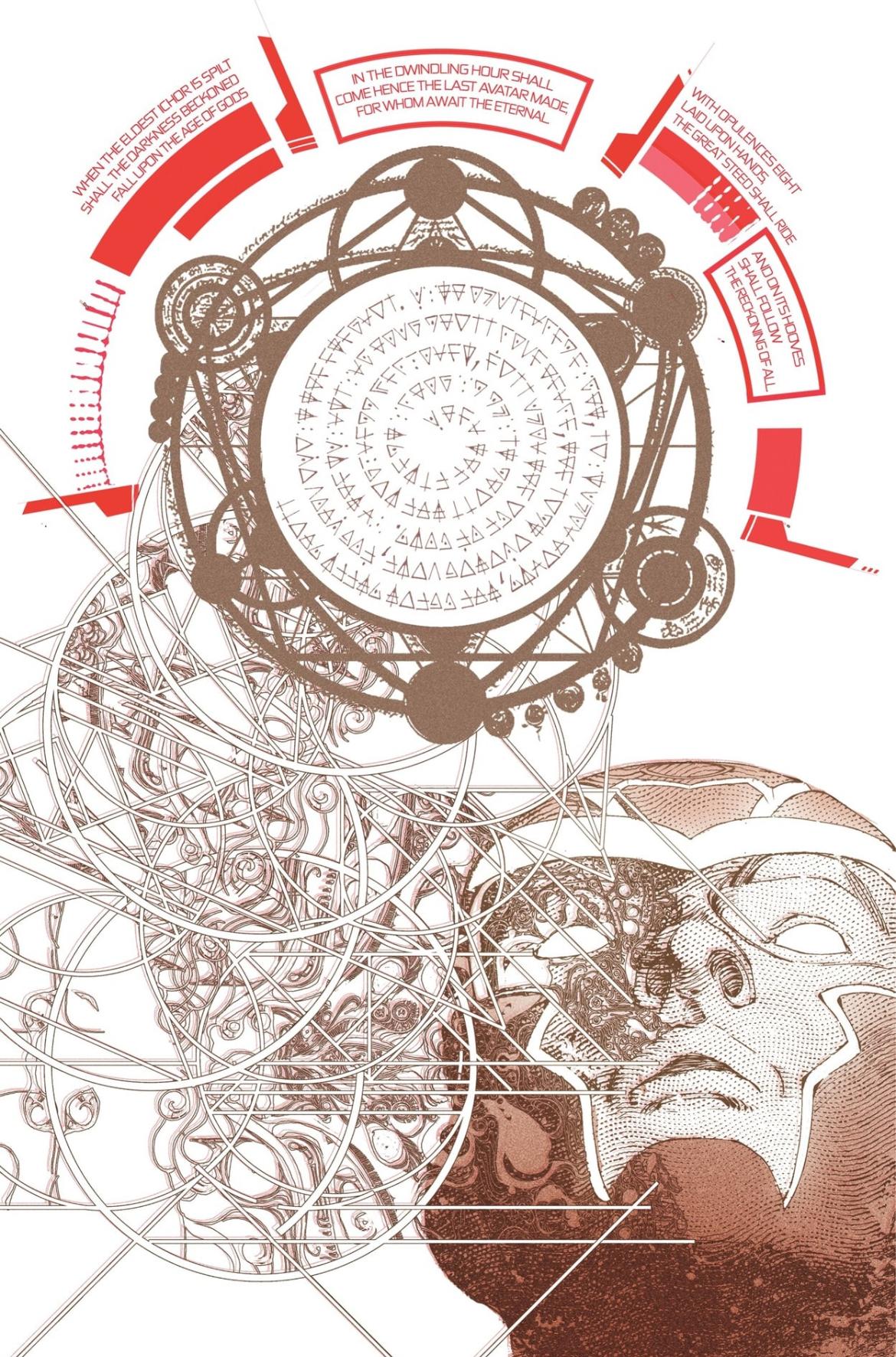

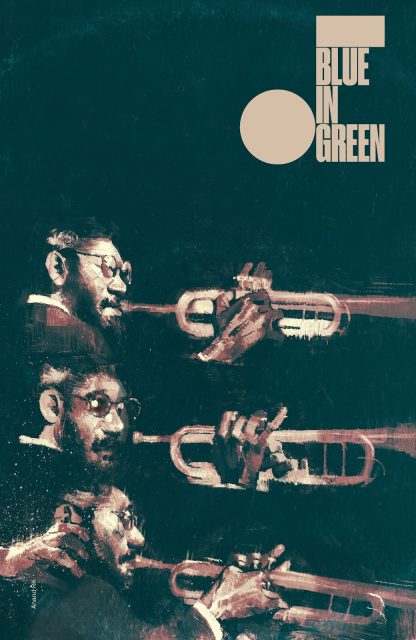

Ram V is an Indian comics writer who has rapidly built a rich body of work over the past decade. Starting with the self-published mumbai noir Black Mumba, he has added to his Mumbai Trilogy with the life-dramaGrafity’s Wall, and the death-drama The Many Deaths Of Laila Starr. He’s done musical noirs (Blue In Green), gothic fables (These Savage Shores), sci-fi epics (Dawnrunner), and even food comics (Rare Flavours). His recent noir thriller The One Hand/The Six Fingers even won this year’s Best Graphic Album —Reprint award at the Eisners.

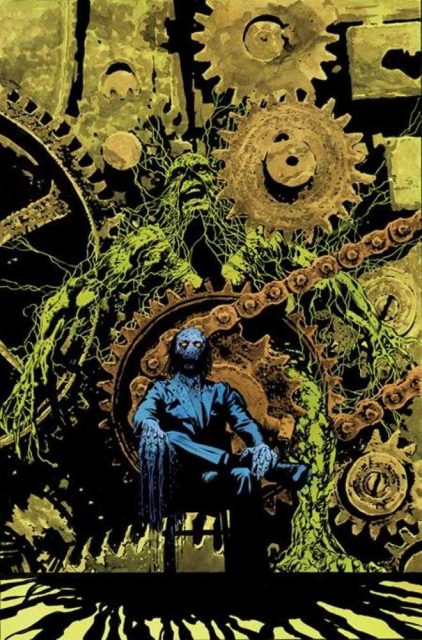

And even outside of a thrilling oeuvre of original material, he’s made a name for himself with his work-for-hire projects likeSwamp Thing, Detective Comics, The New Gods, and Resurrection Man.

Consistently sharp, in the lineage of the British Invasion, and always taken with matters of psychogeography, Ram lives in London and makes very distinct comics. He sat down to reflect upon his long years making comics, and how they’ve shaped him and how he’s feeling about having made a major decision about his future, as he wants to pursue a new and different path. — Ritesh Babu

RITESH BABU: So I think this is a momentous occasion in that it’s been 10 years since you’ve gotten into this thing, comics. And y’know, people talk a lot about breaking into comics, like it’s a prison. And you’ve been in this for over 10 years now, and if you’re in that long, surely it’s a life sentence? So what’s it been like 10 years into this thing?

RAM V: To go back to the prison sentence analogy, it really only feels that way if you’re doing work that you’re not necessarily into.

Yeah.

It doesn’t feel like a sentence if you’re actually enjoying what you do. And I think part of the whole point behind quitting Chemical Engineering and telling stories, working as a writer, was I hated anything feeling like work. And so it’s been 10 years of willful labor. [Laughs]

Honestly, I think in one of our early conversations, I mentioned it, and I know I’ve certainly talked about it with other creators. I said "Every 10 years, you either reinvent yourself or you become obsolete." And of course, there are writers whose careers have spanned decades but if you really look at the work, if the work is any good, past the entire decades of writing, then you can see the writer kind of evolving and changing with the times.

And not just writers. You look at any great artist period. You look at Bowie and the way he kept evolving and changing, right up until Blackstar. All these eras of the artist and every era tells you something. And on the whole, as a culmination, as a sum of all those parts, the oeuvre, the work as a whole, that becomes something transcendent.

Yeah. And it stays relevant and in conversation with where you are right now. Even if it’s not something as expansive and all-encompassing as culture. But certainly, your life has changed over 10 years, why shouldn’t your work change over 10 years?

Exactly. Which brings us to how this kicked off. You reached out to me and said, "Hey, so I’m kinda stepping away from superheroes, and I wanna talk about what’s next." I wanna get a sense of where your head’s at in terms of —why now? Where are you kind of at? You’ve done all this superhero work for a significant amount of time, what are you feeling with that? What’s your relationship to it at this stage? And then, what are you looking forward to next?

I mean look, on one level, there is a part of me that very much came to comics having read a bunch of superhero stuff. Even if that was slightly off-kilter Vertigo takes on superhero stuff, it was still superhero stuff. And so, I wanted to come in and play my part, have my share of that tapestry if you will. And it’s not to say I’ve done that or anything of the sort, but I don’t think it has that novelty for me anymore.

Yeah, you’ve done it for a whole bunch of years now. And you’ve done significant runs as well.

Yeah. I’ve not only done significant runs, I’ve done runs that span the gamut of characters from highly visible, popular properties to my take on something that people haven’t seen for 30-40 years and reinventing it. And taking on stuff that has had prior great runs that perhaps has suffered from having that sort of imperious presence in its history. So I’ve done all of those.

And I found myself in a place where I just went “Okay, what next?”

Because I don’t wanna just go, "Here’s another plot that I haven’t written." I could just do that anywhere. Either there has to be something meaningful in it for me or there has to be something meaningful for the readers outside of the "Oh, it’s entertaining and it’s cool." The entertaining and cool part is given, otherwise I wouldn’t have a job. But you really don’t have any time to just … think about that if you are in the monthly cycle.

I’m in a very lucky place wherein editors are saying ‘Cool! What is that next pitch? What are you doing next?’. Which I recognize is a nice place to be. But you keep doing it, you keep taking advantage of that, if your pitches aren’t truly interesting or genuine, you’re gonna run that line of credit out. And I would much rather go "I’m gonna stop there." I’m gonna go away, read, have interesting experiences, do interesting things, and if I have another story to tell — that I personally feel is interesting and fresh, then I’d perhaps come back.

The industry’s got a long history of fan culture, going back at least to Roy Thomas launching the fanzines and one fan-generation passing the baton onto the next. So there’s a lot of folks who’re like, "Well I wanna write 100 issues of Superman." There’s that temperament of "100 issues of Spider-Man or Batman" as being an accomplishment. But I don’t think I’ve ever associated you with that sort of thinking.

One of the funniest things is in a moment of self-sabotage, one of the first things I said to the editors at DC was, "I am not the guy who’s gonna be writing #236 of something. That is not me." But it’s true. I’m not interested in that. My brain isn’t wired that way. My feet get itchy.

I’ve actually been leaning towards longer runs as my work has gone on. I still do the five-issue mini. But New Gods is intended to be 36+ issues long, if we get that runway. Detective was always intended to be a 30 issue run and we got that runway. So even though a part of me has been leaning towards that, it’s really less the length of the story and more…

Purpose?

Yes, purpose, but also, just the need to have more every month. Why? And I understand the industry works that way. I understand some fandoms work that way but creators don’t have to.

And I’d say it’s not necessarily the way every serialized comics realm works. You look at the French BD market and it’s the kind of thing much more conducive to Frank Quitely putting out work a bit more regularly.

Exactly. And it’s because it’s not on a monthly level. It’s not the serialized nature of it, it’s just the monthly nature of it. To where it falls into this weird in-between space of "I’ve not had enough time to think about what I really wanna do next." The monthly cadence requires pace.

And the artist is also made less important, just because of that brutal grind. The artist just has less time or room to put their stamp on what is a very visual piece of work, when it is a visual art form. They’re much more interchangeable in the landscape, whilst the writer is elevated. Whereas in the BD model, say, Frank Quitely can only draw 60 pages a year. Which means he can’t do a monthly. But he may be able to do a Graphic Album/BD every year. That could work out. That’s just much more artist friendly and he has time and leeway to reflect and put out his best work. You look at guys like Igor Kordej, and his best work is in BDs, not American comics.

Sure. And I think even that comes down to the question of "What are you willing to do?" I mean forget the artists who’re more house-style and generic, let’s talk about the great artists that we look at today. Even Tradd Moore, I have seen pages at his home where he has taken seven days to work on a page versus where he has to deliver a page in two days. And you can see the difference. I’ve seen Evan [Cagle]’s work, it looks different when he takes time. And there’s a part of you that is compromising on what you would like a page to look like every time you go, "Oh there’s my deadline, and I have to send it in." And honestly, it’s not always a bad thing, because I think as an artist you learn a lot in terms of decision-making once you’re forced to make those choices. But once you’ve learnt that, the value of it fades. Because now you’re going, "Okay, but I’ve learnt that. Now I want time to make good pages."

Yeah. The process is instructive, but once the instruction’s complete …

Its value is overstated.

I think it’s interesting that sometimes artists come up and say, "Oh I used to be the kind of artist who took six days for a page. Now things are great, because I only take one day to do a page!" And I wonder sometimes, if we truly grasp what we have lost in that process, too.

I look at a number of artists, when they first come in and break out, "Oh you have a really cool and standout style." Sometimes they’ll even be coloring themselves and inking themselves, doing it all, making all the key decisions and choices. And you go, "Wow, this is striking." Cut to a few years later and they’re doing a Marvel/DC book or two books in that IP realm, and suddenly the layouts are much more flat, much less interesting, because they have to grind out a page faster and faster. And even the coloring, somebody else is doing it, it’s all much more "standardized," much less "them." Far less idiosyncratic or attuned to their distinct sensibilities. It’s like, "Yeah, I suppose it’s functional. It does its job, it comes out on time too," but it lacks the flavor that actually made them special to begin with.

Right. And look, I think a lot of that is because there is a necessity to be part of that industry that creates those monthly comics. I wouldn’t hold it against anyone. There are plenty of artists whose work you can look at and you can tell, wherein they clearly have two lines of work. One is, "Oh I’m doing a monthly comic? This is what my pages are gonna look like," and then another is "Oh I’ve got time to do these? This is what it’ll look like then."

It’s great that some people can compartmentalize like that. But there should also be a space for people who don’t want to work in that sort of framework. And I think certainly, pulling the conversation back to writing for a bit, certainly I have no need, outside of my own excitement, to constantly be working within that framework. And as time has gone on, I have other opportunities that take up my time and interest. And if it ever came down to the choice of "Okay, are you gonna let go of your creator-owned project or let go of the superhero stuff?" Then nine times out of ten, it’s gonna fall on "I’m gonna step away from the superhero stuff."

Yeah, and besides, while you’ve mentioned that you’ve done a lot of the notable ones, more than anything, when I look at your work in that arena, it feels to me that you are one of the very, very few people who really understood the purpose, the vision, and the lessons of the British Invasion and everything that their work accomplished in terms of tackling these American Power Fantasies and interrogating these ideas and assumptions of power. You go back to something as foundational as Miracleman, which takes that adolescent fantasy of idealized power, and then zeroes in on the limitations, the vulnerabilities, the powerlessness of people as much as anything else. All the things we can’t do, unlike this terrifying super-being. And so much of humanity is in our limitations, the things we can’t do, and how that shapes us.

Well on a fundamental basic level, with those British Invasion writers (and some of their American contemporaries), the question they were asking is, ‘How does this mean anything to us? To the human condition? To other people?’. Because on some fundamental level, that’s what stories are about. When they stop being about that, you might as well be watching a guy slipping on a banana peel for 20 minutes and laughing at that. Because it means nothing beyond "This character punched this character." And that kind of meaninglessness is very soul-sucking and soul-sapping to me.

And so even as someone who always made the effort to make sure the stories I did were fundamentally speaking to something on a human level, even on that level, there are things that I would like to do, but are just impossible in a monthly comic cadence and constant sales-watching.

It is very funny isn’t it? People obsess over the sales, oh where is this thing ranking in these sales, who’s on top and who’s below whom, it’s this very strange thing.

It really is. And also, thankfully everything I’ve done has done well in terms of sales. But then obviously in a monthly cadence, because you’re at X or Y number of issues companies are built to look at that and deal with that and be concerned by it.

But it shouldn’t matter to the creator. There’s always been this existential struggle at the heart of the creative endeavor. Don’t get me wrong, you’re not gonna get an opportunity to continue being a successful creator if your books aren’t being picked up and read by people. But there’s a line between "enough people pick up my books and read them for them to be successful" versus "I want the most number of people to pick up my books/I want to write for the broadest possible sales-base." If you cross that line, you risk paying more attention to selling stuff and less attention to making stuff.

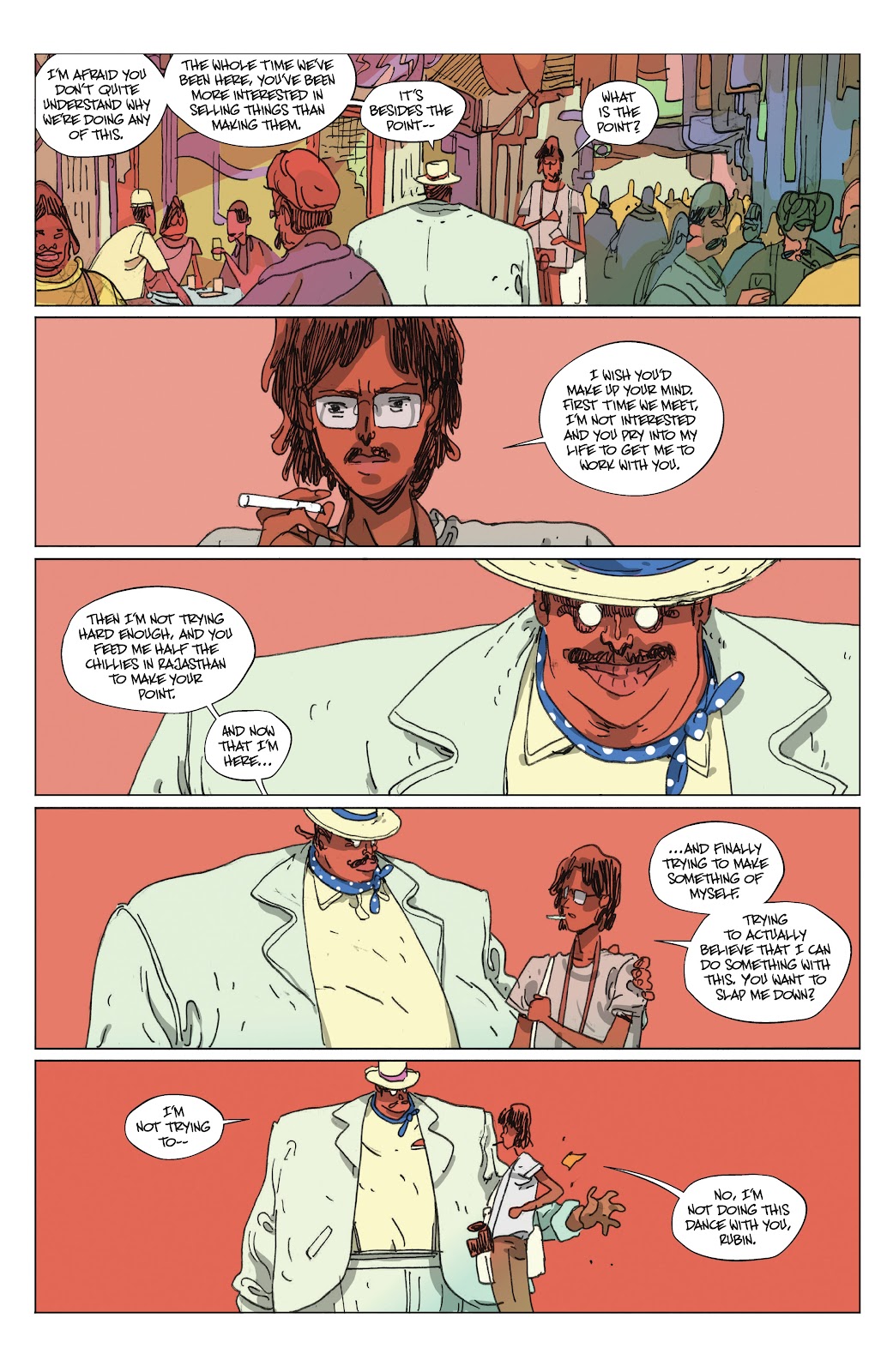

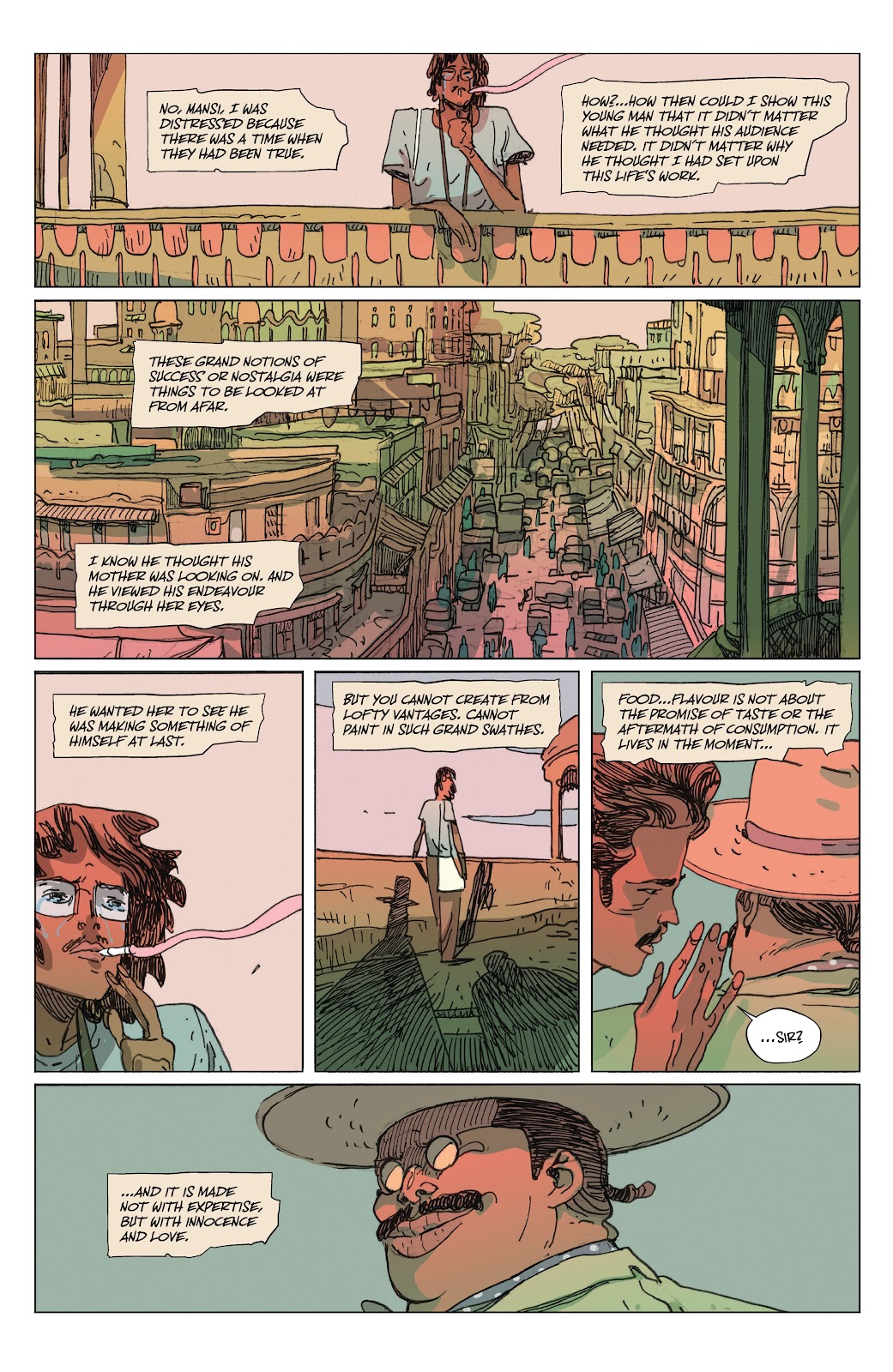

It’s funny you say that because one of the things I really loved about Rare Flavours as a comic is that, while it is about a great many things, one of the things I found really resonant was Rubin Baksh trying to teach this young artist, this young creative person, what it actually means to create. And create not in the commercial sense, because there’s this great scene in #3, wherein Rubin takes Mohan to this spice-market in Delhi, near Jama Masjid. And he’s showing him all these great sights, like a paternal figure, telling him, "Look at this, there’s all this history here." And meanwhile all Mohan can think is "Hey if we can get this shot right here, we can really sell this. The people are gonna love this! They eat this sorta thing up!"

And Rubin’s just kind of baffled and looking at him and is just like "How do I teach this kid?" Then he finally sits him down and tells him "The whole time we’ve been here, all you’ve done is talk about selling things and how to sell things. This is not about selling, this is about making. Making things is not done like this, it’s done from a totally different place." He’s trying to illustrate to him the difference between making art and making content. Making art from the soul as opposed to engineering a hit. Like a salesman.

Completely. And that conversation, if you read that whole book, it’s honestly just two parts of one creator having a conversation with each other. Both Rubin and Mo are parts of me as a creator. And there is that constant struggle, as someone who works in a commercial art medium, between "I need this book to do well and get picked up by readers" vs. "I need to express myself and I need to tell this story because of the way I see things, in my heart and mind." Those two things are always going to be at odds with each other, but I think that’s a good friction to have. The problem is when one becomes king. And it’s less of an issue if Rubin takes over. But it’s far more of a problem if Mo takes over because that way lies mediocrity and banality, just ironing the joy out of everything.

Yeah. It’s interesting, contemporary American comics publishing is so built around Hollywood money. And because of that reality, there’s thus the prevalence of the "X meets Y" comics.

Look, there’s always been money from other industries interested in niche mediums. Michelangelo was getting money to paint the ceiling of a church. So it’s always been the case. I don’t think that in particular is to blame. I think the X meets Y pitches are popular because that is the easiest and lowest hanging fruit. And so I would be pointing at creators and going "Don’t do the X meets Y, do the interesting thing." Honestly, I don’t think anyone in Hollywood says "I want the X meets Y." Sure, they might have a hard time understanding a pitch that’s more complex sometimes. But the great benefit of making comics is you don’t need the X meets Y pitch if you can just hand someone a comic and go "Here, read this." And more often than not, reading the thing is more impactful than pitching. So I’m someone who is a great believer in creators and artists and people who make stuff in any medium, they should have every avenue of sustainably earning a living off of doing that thing. And if that means Hollywood is going to come in and give you a bunch of money to turn it into a film or ask you to be involved in writing the film or art directing the film, great. But that has nothing to do with a mediocre pitch, a mediocre film, or a mediocre comic, in an ideal world. But of course, we don’t live in an ideal world, and it’s easy to pick the low-hanging fruit right?

For sure. You want an artist to aim higher, always.

I’ve known you for many years now, going back all the way to the start, when you were just starting out with These Savage Shores, before any of the Marvel/DC stuff or all the fame that followed. And part of the fun there is watching you evolve and shift across time. I think your work’s matured over time. I don’t think the writer of TSS #4 is necessarily the writer of Rare Flavours #4. Has your process at all changed in all that time? I expect you came into comics with certain expectations and assumptions, but having spent so much time in these trenches, has that cumulative experience transformed your process at all?

To an extent. I don’t know if I would have dared to put recipes in the middle of story pages while I was doing These Savage Shores. I felt much more at ease and comfortable doing it while working on Rare Flavours. And it’s because you have a familiarity with the medium, and you have a familiarity with the person you’re working with to know they can pull off something. TSS, there was certainly an element of me controlling everything that’s happening in the book. And I think I’ve let go of a lot of that control as I’ve continued to work in the medium. Simply because it’s easier to work with people you trust than having to control the work and work with people you don’t trust. I would much rather tell a publisher, "We can’t do this book unless this artist is working with me" than go "I’ll accept any artist working with me" but then I need to control the script. So I think those are things that you gain wisdom on when you’ve been working in comics for a while. But outside of that, I don’t think my process has changed dramatically or drastically. What has changed and part of the reason I am where I am right now is because TSS is something that had been in my head for 6-7 years before I did it. I would say Resurrection Man is similar in that it was in my head for years before I did it. Laila Starr had been in my head for many years. So it was almost "I wanted to write since I was a teenager and then finally …"

You’re getting it out of your system.

Right! Now I feel like I’m at a place where I need to stop and go away and touch grass and breathe some air and have some misadventures and develop those 3, 4, 5 things that are gonna sit in my head for a few years before I go "I can turn this into a story or a book." Not that I’m running out of ideas, but I miss the ability to let an idea sit. To grow and develop itself over time, rather than me having the idea and going ‘And now I’m going to turn this into a narrative’.

The immediacy. It’s a feature of a monthly pop serial form, and that can be fun for certain purposes. But also the ability to sit with something …

Don’t get me wrong, that’s part of what makes you a good writer in that format, the ability to take an idea and develop an execution for it that works. But you don’t wanna always do it that way. Like, my Detective run, I came up with it and executed it within a span of three months. But you don’t wanna always do it that way. I miss the year and a half long work time on Blue In Green, wherein I was just sat there going, "Huh, what do I do next? I have no idea!" That ability to just sit and go, "What next?" That's important for a creative soul. To not have the constant pressure of "I gotta turn in the next script!"

Certainly. And looking at the tail end of your work, like I see your Swamp Thing, that to me reads like you’re getting all the Alan Moore out of your system. I look at your Detective, that feels like you getting all the Grant Morrison out of your system.

[Laughs] You’re not wrong.

And with The New Gods, it’s all of that Jack Kirby out of your system. Just like Resurrection Man or Laila Starr which you mentioned before, there’s a sense of exorcising these things you’ve had in your head for so long in some measure. And now having done so, you’re like, "Okay, now I can come up with new things based on the me of now and my current preoccupations at this precise moment, as opposed to what’s been haunting me for ages."

And I think you need to give yourself the time to be haunted by something for the next decade, if you will. I’m lucky to be able to do that, and so I really should just take advantage of it rather than going "What’s my next gig?" Not to say I intend to disappear and go learn how to craft Italian footwear. [Laughs]. I’m certainly gonna be doing a lot of work that is not in comics. And so it’s nice to be able to take that time and noodle away at comics ideas that I intend to pick up on and work on.

Yeah. I know you’re a huge Manchester United fan, and one of the things I really like about Sir Alex Ferguson is the man’s longevity. There’s various phases of his career. And he’s done so much, but if you look at his career, the thing he would do is periodically refresh his staff and bring in new people with diametrically opposed ideas and different viewpoints, and what he would do is let them help him adapt and change and transform. He always kept the essence of who he was and his vision consistent. If you knew what SAF was about, he was still that, but he was also utterly open to evolving and changing.

And he was famously a great man-manager. Not necessarily the best tactician. It’s the sign of a great leader and manager to recognize "This is my thing, but this other thing is not my thing" and so every time he felt like football was tactically evolving around him, he would just go and get someone who had the tactical knowhow. When he went and got Carlos Queiroz to be his assistant, it’s because Queiroz’s tactics were of that time and of that moment. Same thing with Mick Phelan after that.

I think he was very good at recognizing what was not part of his wheelhouse. Just one of those people who was famously great at delegating. He didn’t need to control everything. He had to have the final word on everything, but didn’t need to do everything himself. And the thing I really take away from Ferguson particularly is his inability to ever become complacent.

Yes!

He would get rid of people when they were at their peak of their performance for him. And you would always go, "That’s crazy, why would you do that?" And three years down the line, you’d realize, "The people he replaced them with are now gonna be here for the next 6 years and carry his team forward." He got rid of Ruud when Ruud was scoring!

Beckham even.

Beckham! And Stam. Tho he admits Stam was a huge mistake [Laughs]

Well, you can’t win 'em all.

You can’t! But I think that’s the sign of a great manager, because it’s so much easier to go, "I’ve built this team, it scores goals on its own, I have nothing to do." Rather than that, he’ll go, "I’m gonna take away someone who scored me 40 goals last season and I’m re-jig it so that I can continue to win." I think that’s a very admirable quality and something I try to translate to my own career.

So many people would be satisfied with just winning once or having even a kernel of the success that SAF did. Most would go,"I’m good, I’m satisfied." He was a freak who just could never get like that. He needed the rush of being able to do it again and again.

This is true of every great in every sport. Like, I have this conversation with Dan [Watters] and Alex [Paknadel] sometimes. And I try to be a very nice person, but I have mean streaks and I attribute them all to bad sports analogies [Laughs].

So whether it’s [Michael] Jordan in The Last Dance making up a rookie insulting him just so he could get himself hyper-motivated. That is some heinous stuff. Just make up in your head someone insulting you just so you can go out and perform better. But I would 100% be at risk of doing that — letting outrage drive effort.

And then there’s that famous Kobe Bryant interview wherein he’s sat after winning Game 2 or 3 of his Finals series, and the interviewer says, "That was a great victory, but you don’t seem happy, you’re not smiling," and he looks at him and goes, "Have we won the finals?" The reporter goes "No," then he replies, "Job’s not done. What’s there to smile about?"

I think it’s a sign of people who are hyper-focused on what they do. But I’m also very aware that it’s not a very healthy trait to have. So it is simultaneously amazing and self-destructive. So everything in context, in proportion.

For sure, for sure. And that leads into one of the things I quite like about your work. I look at American mainstream genre comics of the direct market, and there’s a real insularity. There's art inspired by art and there’s art inspired by life. And in the DM, there’s a lot of art inspired by other art, other genre stuff. But when I look at your work, rather than the art obsessed with certain power fantasies or particular insularities, it’s a lot of art that’s really taken with life. Even things like Laila Starr or Rare Flavours, which have these mythic figures of great power — death, demons — what you’re really doing is saying "Let’s take this mythic figure and then use them as a vehicle for this human character story, like a Darius and his entire life growing up or a Mohan and his entire journey as an artist." These ideas are only valuable in that they help contextualize the reality and life of this very human, messy individual that’s really trying and failing. It’s all about these people in all their powerlessness and frailty and all their weakness.

And that’s what I find so engaging. Because so much of American genre comics is about this obsession with power, these power fantasies, but a lot of your work is just about using them instead as frameworks for the actual human shit. Even something like These Savage Shores, there’s Bishan, who’s this powerful Rakshas warrior, but the conclusion is he fails to actually save the one person that he cares about. His human partner Kori. It’s a tragedy built around that, that inability, the futility of power.

If you look at it, my narratives are almost entirely about powerlessness.

Yes! This is the appeal!

Especially when you take the context of power fantasies. Take New Gods for example. The entire narrative is driven by "Yes, you might be a god, but you have a terrible relationship with your brother or you couldn’t save the one kid that was actually loyal to you. Or you have all this tremendous power, but you’re an insecure wreck who can’t even trust his partner to say ‘Hey, I’m in trouble, I need help'."

It’s a very human thing.

It is, and I think if you don’t have that, then the story necessarily and effectively becomes about conflicts outside of that. And they are much less interesting conflicts because the one conflict that is universally true to every human being is anyone who tries to achieve anything is doing it so they don’t have to feel powerless in some form. And the great sort of dismay of the human condition is that no matter how high you get, you’re going to feel powerless at some point in time. And I think giving up part of that ability to be okay with being powerless, if you’re not okay with that, you’re giving up some part of your humanity. And I think I’m much more interested in characters who are capable of being powerless, despite otherwise being very powerful, if that makes sense.

It does. And it segues into another question I have. You’ve talked a lot about what you’ve learnt in terms of what to do. But given 10 years is a long time, that sort of longevity also teaches you just as much is what all not to do. So what are Ram V’s non-negotiables, if you will?

Don’t do anything that sacrifices your artistic vision. I know it sounds like a thing you say once you’ve gotten to a point where you can swing that. But try not to. Because every time you do do it or have to do it or feel like you have to do it, that’s a small portion of your soul being chipped away. There are pieces of work that I’ve done, that I look at now — some of them celebrated, others not so much. But even the celebrated ones, when I look at them, all I can see is "If only I had gotten to do the thing I actually wanted to do, it would’ve been so much better!"

And creatively, that’s not a great feeling to have. Because say I had gotten to do exactly what I wanted to do, and it turned out to be worse than it is right now. But that "worse" is an objective third-person reading of it. To me, it will never be worse. To me, it will always be the best thing I did because that’s what I set out to do. And the obvious thing to remember then is comics is a collaborative medium. You’re meant to make compromises and accommodate each other’s visions. That’s true, that’s why it’s very important to find a collaborator where you never feel like you’re cutting your artistic vision off to enable that person, and it should be the same for them. They should feel like their vision is shining because they are going to accommodate you. And I think that’s the magic of great collaborative relationships in comics. It’s both collaborators feeling like they’re executing their vision without compromise, or with the sort of compromises they’re willing to make that doesn’t really affect what they set out to do in the first place. The moment you make compromises to what you really sought out to achieve, then the question is "Then why do any of this anyway?" Then you might as well be doing any other job. If you don’t care so intensely about what you want to do here, then why are you in this medium?

That would be my one piece of advice. Persevere to protect artistic vision at least as far as you can.

You’ve talked about the grind of the monthlies and wanting more time, wanting to feel the way you felt with Blue In Green and taking your time. You entered the direct market landscape at a very specific point, one I would say is a bit different to right now in some measure. How do you see the sea change from then to now? Or is there a change at all? How do you view it from then to now?

There’s obviously a change. Things have gotten difficult, distributors have fallen off. There used to be a near-monopoly, now there are multiple distributors, but are any of them healthy and doing well? [Shrugs] Who knows? Beyond my area of knowledge.

But I think the Direct Market has certainly changed, in challenging ways, but also in some good ways. I see more younger people picking up comics that aren’t necessarily the usual kind of comics that would sell all the time. I see a lot more interest in that Vertigo-esque era of comics that I grew up on. Those are all good things. I think this will continue to be the case. Markets will change, they’ll adapt, some of them good, some of them bad. But for me, I just want to make things, wherever, however.

Yeah.

And I don’t mean that in a flippant way. Of course I care about the health of things and the industry and all of that. But I think it’s important also for me to be in a place creatively where if I make something and no one buys it, that’s okay.

I don’t think people remember, but I did a comic called Miracle Men with Anand RK.

I remember this one. [Laughs]

We literally stapled it together and went to a convention and distributed it and gave it away for next to nothing. And it’s probably the comic that Anand has put in the most time and effort into because he actually painted it on a canvas. But you have to have the ability to do stuff like that.

To be able to do the "New Gods, no one had read that book in years and #1 did great in sales, hurray, great." And that was part of the direct market and because of the retailers and the enthusiasm in the direct market that book sold well. My point is, as a creator, I wanna do all of those things, but I also want to do the thing that I am preoccupied with doing, that nobody else cares about. And that nobody else may want to read. And thankfully, I’m in a place where I can confidently do both those things without worry. And that’s a lucky place to be. But as long as I’m doing the former every month, none of the latter is happening. And that’s not good for the soul.

So I guess that brings us to the big question of — what is your vision of what’s next for you? What’s inspiring you? Whether it be other people’s work or some subject or perhaps just other artforms. What’s the direction you’re looking at? What is your sense of where you’re headed?

Well, there are a few things I’m already doing, which I can’t really talk in too much detail about. But I wrote my first feature script, which was great. I did work for a video game, which in due course will be announced and what not. I continue to do more work in the video game space, and I’m also doing work in the animation side of things as well. And these are all things I had always been interested in, from the very beginning. And so getting to do them now means I have a lot of work, and I have to manage how much of that work is here versus there.

But obviously I didn’t go out and set up an animation studio myself and decide to do it. So this is all very commercially-driven work. But it’s interesting to me because it’s all in a different medium. Different rules. And so, I feel like I’m messing with something new. It has that novelty for me, and I’m very excited by that.

On the personal project side of things, I have a few projects that I’m not sure are publishable in any existing commercial format. Like, I’ve wanted to do an illustrated-and-written-by-me thing.

Yes!

But it’s not really comics. I would say maybe illustrated prose that I’ve wanted to put out, but it has a quirk in that it reads like a found journal. And the formal thing to do with it is, at least on a smaller scale, for every copy to feel like it’s somehow unique, somehow…

Personalized?

Yes, but not just personalized. The narrative itself changes from copy to copy. And so you get a slightly different version of the same story depending on which copy you read. Or maybe you get a slightly incomplete but different version of the story. And your story is only complete if you’ve talked to or heard of other versions of that copy. An interesting exercise to do. And you might think this sounds great. But anytime I talk to a publisher about this, they go, "Oh no! We cannot do this!"

This is for the sicko experimentalists and freaks as opposed to the big publishers who are businesses.

Correct, correct. And this is exactly the kind of choice that’s easier to make when not committed to doing X number of issues on a yearly basis. So there’s that project.

There’s also another project that falls in my mind between design, prose, comics, and animation.

Oooh.

And it is sometimes just designed illustration. And sometimes it is sequential art. And other times it’s animated. And I have a sense of how to put this together and I know what the story is, and anyone I’ve ever talked to about it has always had this, "You’ve blown my mind!" expression. Including people who are in animation, people who are in filmmaking, people who are in comics. The only thing I can say, very excitedly, is that Al Ewing is doing some voiceover stuff for me for this.

He does have a great voice.

Yes! So hence, exciting stuff. But again, something that I’m not quite sure where or who would be publishing it so I’ll just find a way to do it myself. So there’s a lot I want to do. And then there’s writing a novel, which I’ve always aimed at writing when I started. And I still haven’t done that, so at some point, that will become a thing I focus on as well. And then I’ve been very lucky in that all the creator-owned works I’ve done so far are in various stages of development. And I’m involved with a lot of those things, so it’ll be interesting to see where and how that involvement takes me. And then beyond that, there are creator-owned comics that have been put on the back-burner because I was doing monthly superhero stuff. There are artists I’ve told: "Three years from now, we’ll get together and do a book!" And I intend absolutely on doing all of them, so it’s exciting to be able to go back to that.

Does that make sense?

It does!

Now that I narrate this, in my head, I’m still thinking, "I’m doing too much." [Laughs]

It’s a matter of organization, right? So long as you have that right, it is doable. I look at something like Blue In Green, and it is wild to me that you were able to do it while also doing all of the other work you were doing at the time.

It was wild. But it felt like I had a lot more time then. You have to remember, I have a four-year-old running around that I want to spend time with.

It’s true.

So I definitely will be working at a slower pace, maybe more picky with the projects I take up. But I say that, and then there’s this huge 3-4 year-long project on the horizon that we’ve discussed offline plenty of times.

Yeah [Laughs]

That will take up so much of my time and effort that it’s not even funny. So, we’ll get there. Somehow. But we’ll get there without being pressured.

It’s interesting you mention the fatherhood aspect. I look at something like The Swamp Thing, right? And the thing I love about it is, while it is a lot of things, at its heart it’s about a guy and his really messy relationship with his father and how that dovetails into his relationship with his brother. And a lot of it is trying to reckon with his relationship with his father and just his father’s passing. And from there we get to The New Gods, about a young father who’s had all this experience with his own father and is like, "Well, what kind of father am I? And what kind of father do I want to be? And let me think about what my father did to me."

The New Gods is really about a bunch of terrible fathers doing terrible things in the name of fatherhood. [Laughs]

Yeah. But there’s a lot of you in those books as well.

Anywhere I go, there’s paternal conflict.

It’s certainly a big part of your work! And that flows into the other thing I wanna ask. Can you talk about the refinement of your voice over time? How has that process been for you in terms of chipping away until you’ve found "Okay, yeah, this is me in the truest sense."

I saw a comment or review that someone screenshotted and sent to me where it said something to the effect of ‘I love reading this, but I feel like I need a PhD to read it’.

And I think that summarizes my aesthetic entirely. Without being too flippant about it, I like my stories to be that level of "Wait, what does this mean?" It’s complex, and it requires the reader to fill in the gaps. It’s this uncomfortable place wherein you don’t expect all the questions to be answered in the story. And I think that’s always been part of my voice, part of my aesthetic. But I think you see it less with something like These Savage Shores. And perhaps see it much more with something like, say, Resurrection Man. I certainly see that as being a refinement. That’s not to say These Savage Shores isn’t complex. But it is certainly…

It’s much more giving with its answers.

Right. It doesn’t make you uncomfortable or challenge you in ways that make you go "Wait what? I need to read this again to understand what I’m supposed to do here." And maybe something like Resurrection Man is of that sort or type and Rare Flavours was something that was much more challenging because it required you to make these leaps of narrative logic, where you were reading a story, but there’s recipes in-between. "Well, what am I supposed to do with that?" The answer is "What did you do with that?" Did they push your narrative forward? Did they add something that allowed you to complete things that I didn’t fill in for you? I think doing stuff like that is very much something I enjoy, and something that has become more prevalent in my work.

I’m always amused when people use the term "pretentious." And so my response is always "It’s only pretentious if you don’t mean it."

[Laughs] Yeah. You gotta have something to express and you have to commit to it.

And also, not everything has to be said in its simplest terms.

That’s the thing right? People often look at art as a didactic form of messaging rather than a mode of questioning that encapsulates the human experience.

But it’s also this necessity to be fed entertainment. And don’t get me wrong, I’m here to entertain you. But I’m not here to feed. I have no intention of feeding you entertainment. I want you to get on the tightrope with me and fear falling down. That’s the kind of entertainment that I’m here to provide.

I’ll give you an analogy that’s been stuck in my head.

I had a dish at one of these high-end molecular gastronomy forward restaurants once. It was really funny because the menu just said "Eggs and Beans." And you’re thinking, "Wait, I’ve had that before, I’ve had an omelette and beans. What is the big deal?" And then it comes out on a plate, and it is exactly that. It is beans on the side and a fried egg in the middle. And then you dig into it and you realize, the "fried egg" is white bean curd, and yellow bean jam in the middle. And the green beans on the side are egg whites rolled into perfectly long stems of green-beans. It’s not until you bite into it that you realize, "Oh, wait, the beans are the eggs, and the eggs are the beans, what’s happening?!"

Now, everyone’s eaten eggs and beans, right? There is zero entertainment to be had from just having eggs and beans fed to you on a plate. And yet this way of preparing eggs and beans has suddenly made that food so much more entertaining. I am giving you the beans that you thought were eggs.

See, now we know why you wrote Rare Flavours. Now there’s a comic entirely caught up in the idea of "Sometimes the right flavor takes a bit of effort, it doesn’t come easy." Maybe you’re gonna have to endure a bit of heat on your tongue, maybe it won’t be the most comfortable to take in at first, but once you get into it, the experience is worth it.

And some stories are meant to be experienced that way. And they only work if you experience them that way. And there must always be room for that, that always has to be the case. And I think we should stop using these two terms to describe work. Pretentious, because sometimes it belies your lack of understanding if the work is any good. And filler. These are the two words that I dislike. There is nothing that is filler. Everything is story. There’s badly-done story and well-done story. But there’s no such thing as filler.

And also, art doesn’t have to be purely or primarily functional. I look at a lot of your stuff, and it’s very experiential. This is trying to get across a vibe or a feeling, there’s an idea being illustrated here that’s not necessarily a "Here’s a Plot Thing," but it’s more so getting across a certain sensibility.

You go to music, and there’s all kinds of music. Some music is perhaps more functional and direct. But some music is just about luxuriating at length in a feeling. You just have to feel it. It can be a bit more difficult but that’s fine.

And to go forward with this analogy. Ever since The Swamp Thing, you can find a lot of Tool lyrics in my work.

Of course.

And if you look at a Tool album, there’re like 17-minute tracks on there that are unplayable on the radio. Because the intro is the length of a usual radio song. And yet, there’s room for that. And there’s a place for that. And there are obviously people who call Tool pretentious as well. But there has to be room for that. Otherwise we’re all just listening to the same chord progression with vaguely altered lyrics or whatever version of that. Not to say I dislike any of those things but there has to be room for everything, room for every vibe. Otherwise you’re closing yourself off to good art, but also, and even worse, you’re ironing the wrinkles out of culture.

Wherein culture is becoming this mediocre smooth AI-rendered film. Nothing has edges, nothing is specific.

Yeah. And I think it helps to be an artist who doesn’t particularly care about validation, but is instead focused really on the process. There’s not as much of that in mainstream DM comics, as people obsess over the sales or reception or what have you. The understanding that the work is the work, and that it is in itself the reward, rather than anything else.

Genuinely, creating art and getting paid are two different and important things. And should necessarily be treated that way. It’s very important to get paid to make art. But getting paid is not an intrinsic part of making art.

Yeah. I see your work, and there’s such a sense of "No, see, this is for me. It’s cool if anyone else is entertained, but this is me entertaining myself." And I suppose it’s also why you’re stepping away from superheroes. You’re someone who wants to entertain yourself first and foremost.

I mean, I’ve done one thing for such a long time that I’m starting to get bored by it. And so I’m gonna step away from this thing that I find myself feeling a little bored with. I’m gonna go do a lot of other stuff that’s new and interesting to me.

The post ‘You have to reinvent yourself every 10 years’: A talk with Ram V appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment