"I understand the reason why/You're sentimental, 'cause so am I” — Cole Porter, “De-Lovely”

My junior year of high school we performed the 1934 Cole Porter musical Anything Goes. I recently watched the filmed version of Kathleen Marshall’s 2021 London production of the show, which makes the case for Anything Goes as one of the great musicals. The plot is thin, even by the standards of musicals. As with comics, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s laugh out loud funny. The dancing in this production was top notch. The cast was brilliant. I think Sutton Foster can do no wrong, and if her acting and singing and dancing won’t seduce you, her outfits will. Robert Lindsay may not be the dancer he was in his younger days, but he’s as sharp as ever. Felicity Kendal is always a delight.

What makes the show great is the songs. There is a reason so many have become part of the Great American Songbook, so that even if you’ve never seen the show or heard of the show, you know many of the songs: "Anything Goes." "You’re the Top." "I Get a Kick Out of You." "All Through the Night." "It’s De-Lovely." "Easy to Love." "Friendship." "Let’s Misbehave." The not-great songs like "Blow, Gabriel, Blow," "Be Like the Bluebird," and "There’s No Cure Like Travel/Bon Voyage" are hummable and better than most.

My teenage theatrical endeavors impacted me. That combination of knowing that the material is beyond what we’re capable of and yet taking the work so seriously. Being driven by passion, informed by a punk ethos. That Judy and Mickey can-do, putting-on-a-show-in-the-barn attitude. Comics are a lot like that. They can be, at any rate. Despite my own neuroses, and the parental philosophy embedded at a young age that anything less than perfection is worthless, that punk ethos towards art and life remains dear to my heart.

***

Starman is a story about the United States. Not the one we learned about in civics class. Not the golly-gee willikers, apple-pie-and-baseball bullshit that Ivy League-educated, far-right populists talk about while deifying “the founders” and pretending that history is only what you learned it was in first grade and anyone who tries to teach anything more complicated than that is desecrating those buried in Arlington. No, this is “The Old, Weird America” as Greil Marcus titled one of his books.

Starman is about the old, weird America. And the old, weird American comic book. According to an old TCJ interview with Robinson, he struggled to get work because people at DC saw him as too Vertigo for the DCU while people at Vertigo saw him as too DCU to be Vertigo. That strange, unique, in-between space that in this series he managed to make his own and which made so many of us so passionate about his work. Which is all well and good, but it can be hard to actually get your foot in the door to do that, or to do it consistently enough to make a living.

I think some of that interest comes from being European and coming to the U.S. How many of those old Vertigo series involved road trips — Swamp Thing, Shade the Changing Man, Sandman, Hellblazer, Preacher, The Invisibles, Outlaw Nation. Stories no doubt full of reference photos that these Brits took wandering the highways and back roads, deserts and mountains, wide open plains and bustling cities of the Western United States. Living out hobo dreams born of old photographs and movies they saw as children and young adults, inspiring visions of escape and freedom and wide open spaces. Those things that the US has for centuries promised to Europeans who felt trapped and hemmed in by Old World values and history and geography.

Road trips where somewhere north of seventy miles per hour down lonesome stretches of highway, the fading light of the setting sun hitting just so that it sets the landscape ablaze, a sight that brought to mind Western movies and Road Runner cartoons, and all those four-color American comic books that helped to inspire visions of the future, of their future. That led them to the road and what it promised, that led them to this road, where cresting the Continental Divide, the horizon jumps, the dream of America and the reality crashing into each other with tectonic force.

Calling him Vertigo as those people did though misses Robinson’s point. Because this wasn’t some weird fringe idea, some mature readers concept, some wild European fun-house mirror notion of the United States and DC Comics that corporate employees born on this continent had to squint to understand. Robinson’s whole point was that all of these ideas and concepts, all this strangeness and zaniness, was baked into the very DNA of the place. Though so much over the years has been changed, eliminated, elided, retconned, and memory holed. The intentional and unintentional curation of what gets reprinted and what doesn’t.

That’s before we get into the Comics Code Authority of it all.

Because the DCU is a landscape of Solomon Grundy, born on a Monday from an old children’s rhyme. The Floronic Man. Hawkman and his weird Orientalist amalgamation of past lives in Egypt, magic, strange metal, old weaponry, and aliens. The superhero who gets his powers from being a drug addict. An ex-rail worker with a magic ring that doesn’t affect wood. Zatanna and Etrigan. Balloon Buster and Haunted Tank. Tomahawk and Jonah Hex. A bondage-loving queer woman born of female pathogenesis teaching the man’s world the joys of loving submission. Not to mention all the detectives, pirates, lost souls, and misfit inventors.

It’s easier to place all that weirdness “over there” in its own space so the rest of us can pretend that it doesn’t exist. Those weird stories with strange artwork and designs can exist ... somewhere else. That way the DCU can function in a vaguely “realistic” manner drawn in a vaguely realistic fashion. Comics are serious, after all. Far too serious for romance or humor or wackiness or surrealism.

So much of America and Americana is strange and unusual, weird and goofy. It’s the sacred and profane, the “cradle of the best and of the worst.” It’s always been that way. The United States is exciting. It’s dumbing everything down. It’s the intellectual vanguard. It’s looking to the future. It’s stuck in the past. It’s the thesis and antithesis — and sometimes even the synthesis, as well. This is Tin Pan Alley and ragtime, jazz and blues, comic books and broadsheets, funeral dirges and hobo songs, gospel hymns and gangsta rap. This is the land of Cotton Mather and Mickey Spillane, Emily Dickinson and Toni Morrison, Walt Whitman and Nas. Not to mention Jack Kirby and Will Eisner. It’s Frank King and Chester Gould and Walt Kelly and Milton Caniff and their strange, unique and contrasting visions of the nation dueling it out in the funny pages.

I would guess that Robinson loves all those wild strange possibilities. The almost impossible to synthesize and explain it all-ness that this country is at its best. That sense of the possible that seeps from the Jungian collective unconscious into our pop culture. In recent decades, comics hasn’t liked wacky, weird possibilities. Not just comics. The national mood has darkened and so has public life. Back in the twentieth century, the 21st was something grand and mythic, filled with excitement and progress. The idea of it was almost fictional. In reality, this century has not been a vast improvement over the previous one. While I believe that life for ordinary people in 2100 will be better than today, the next few years are going to be bleak. It’s no wonder that our collective mood is dark. This is why DC has published so many rape-y and murder-y comics in the last 20-odd years.

Art emerges from a cultural space. I believe that culture shapes behavior, or as Heraclitus argued more than two thousand years ago, geography is destiny. In the 21st century, something like Starman wasn’t of interest. A loving couple like Ralph and Sue Dibny solving crimes wasn’t of interest. Raping and murdering them, though? DC’s Identity Crisis and Marvel’s Civil War were made while the United States was a nation at war. Stories about superheroes behaving like horrible villains in the name of righteousness. Comics about “good” people doing monstrous things. That’s not a coincidence. Art is not created in a vacuum.

***

I first learned about Starman from the promotional poster, which had been placed near the doorframe of the comic shop I frequented. A cropped version of the Tony Harris cover to the zero issue with the famous Oscar Wilde quotation: “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” I had never heard of a superhero named Starman. I had not read Zero Hour, the reason why all of DC’s October 1994 titles were numbered #0. I was vaguely aware of a science-fiction film called Starman, but had not seen it. I had no context for it, but I liked the image, I liked the quotation, and even if I didn’t like it, it was new, so a good jumping on point.

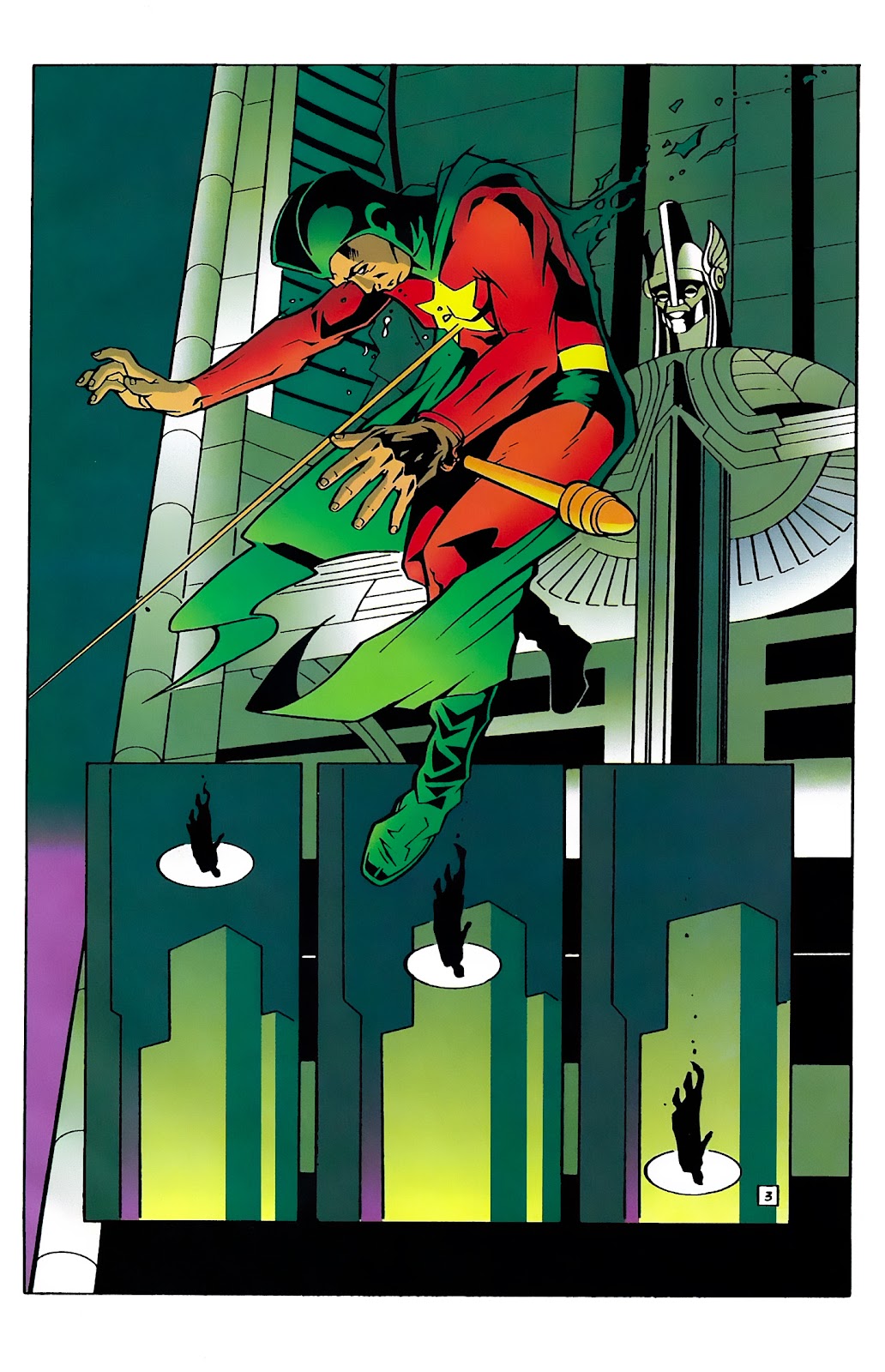

Harris’ art improved, as did his sense of design, over the course of his run on the series before leaving with issue 45, but it was a great first cover. An iconic image that I have always had in my mind’s eye thinking back on the series, even as it clearly shows signs of being an early image, with small details changed in the comic. A great introduction to the character, perched over the city with a strange looking weapon.

“A new generation of super-hero” the poster promised. In the literal sense of being the child of a Golden Age character, who I think was mostly forgotten by this point. Jack Knight was a reluctant hero. One who hadn’t dedicated his life to this pursuit. He studied martial arts for a time because he was interested. He painted until he grew tired of it. He was an antiques dealer who was more interested in the past than in the present, in many regards. A person with a deep knowledge of many different subjects. A generalist in a way that brings to mind that famous Robert Heinlein quotation:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

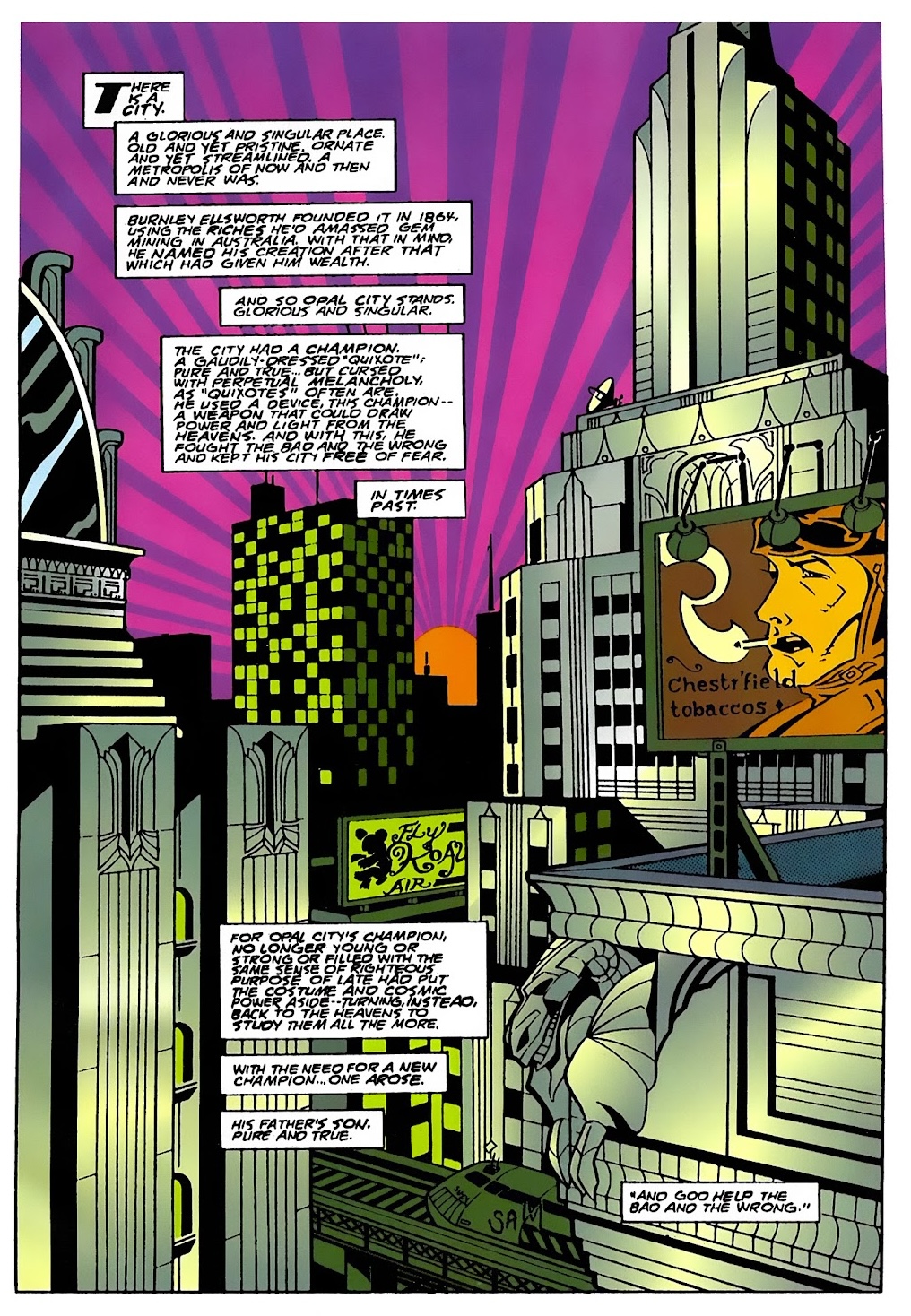

The first page of that first issue is a splash page of a fictional metropolis, Opal City, in all its art deco glory. An ugly modernist glass rectangle in the middle distance, an elevated train, billboards for “Chesterfield Tobaccos” and “Fly Koala Air.” This was a city that never was. A throwback to the old fictional DC Comics cities – Metropolis and Gotham, Keystone City and Fawcett City, Hub City and Midway City. There was a charm to them. Why not create a fictional city to play with? Perhaps that was an intentional nod to those who may have picked up the issue to tie into continuity, to the people who loved the Robinson-scripted miniseries The Golden Age, to past characters and series. Opening with this “metropolis of now and then and never was” set the series firmly in this world bridging the past and the present before they’d introduced the characters and the plot.

This was all being narrated by … someone? We would of course come to learn that it’s The Shade, but it was making it clear that this was a story. A superhero tale. Anyone expecting something nostalgic and comforting, would learn that wasn’t on the table. If you thought a book being narrated by a villain was discordant, that’s nothing compared to what Robinson had planned.

In that first issue, Jack’s brother David, wearing an absurd looking superhero costume, is killed by a sniper’s bullet. Yes, it was the original Starman’s costume, which I did not know at the time, but on rereading, it looks absurd and the color scheme is ugly. This is the kind of costume that comes straight from the Golden Age and there is a reason why so many of those characters have been redesigned so often over the years.

Back to my point, by page 4 of the first issue, the title character is dead.

Only then do we meet Jack in a flashback from earlier that day. A cynical wiseass, who mocks his brother, and by extension his father. In this initial scene Jack comes off as unlikeable. More than I remembered and more than I expected. That snarky attitude — especially coming out around family who push our buttons even as we push theirs — would mellow a little over time, but it’s a striking choice. A change from the many Peter Parker clones, characters who are quiet in life but become verbose when they put on a costume. Their anonymity another superpower. Jack for the most part is internal when he fights. His mind flitting about in an ADHD-like jumble of obscure pop culture references, while in his day-to-day he’s trying to be cool and collected as he verbally jousts with people.

As introductions go, it’s a good first issue, with Jack and his father both barely escaping being killed. A larger story at play. An unknown narrator. Unanswered questions, but ones with answers and just enough mystery to keep the reader in suspense.

I quoted Heinlein earlier, but I don’t think that Robinson had that in mind. While the character may have some overlap with the wiseass/slacker Generation X sociological cliche, the comic doesn’t lean hard into that. I can only imagine that Robinson and his editor, the legendary Archie Goodwin, would have had some thoughts if that was a note they were given. Imagine how poorly the comic would have aged if they had leaned into it — and if you’re not sure what that would resemble, think about how comics handled beatniks in the '50s, or hippies in the '60s or '70s, and shudder.

They didn’t go for the cliche because they were talented and thoughtful, but also, I think both understood the series was at its heart about fathers and sons. About two men who were similar, but had been shaped in such radically differently ways that for all they had in common, they could not help but butt heads. It’s a classic story. One that likely appealed to so many of us who were reading it, even if we weren’t conscious of it. We knew that we were different from our parents, even if we didn’t understand why or they didn't understand how things had changed. The comic didn’t need to lean into what was hip at the moment. The comic was set out of time, after all. Robinson understood that their relationship and how the characters were situated, was the key to the series, and it has remained memorable in part because of that relationship.

This may have been easier at that particular moment in time than now, though that could be nostalgia. There was such a clear contrast between Generation X and their Baby Boomer parents and their Greatest Generation grandparents. The economic circumstances, social attitudes, pop cultural references, different childhoods and child-rearing styles, was so distinct for each generation. Also, the fall of the Soviet Union and Perestroika had marked a new era, which gave even greater weight to this.

Of course the precise timing and what it all means in Starman is unclear, as the “timey-wimey stuff” in comics always is. Both men are adults. Ted is a retired superhero and widower, and Jack is a businessman and a superhero. By making Ted a Greatest Generation older guy and Jack the younger Gen X guy, they’ve managed to avoid dealing with the mawkish Baby Boomer nonsense that has occupied so much cultural real estate from Field of Dreams to the original Quantum Leap.

Ignoring all that, we understood the basic outline. Jack was a younger man, his father was an older man. Along with “tall, slender man” and “short, stocky man”, it’s one of the classic duos.

***

Most Golden Age comics are bad. They were considered disposable reading material for children, and I would argue that a random picture book today is better written and drawn than almost every one of those comics. Some of us read old pulp fiction, but we’re usually reading the writers who defined and transcended it. That said, I've read comics from that era which are so startlingly good. They have quirks and approaches that date it to a specific time and made in a style that conforms to that era, but they’re so contemporary and interesting.

Bob Kane’s original Batman comic is bad, but to read the Bill Finger-scripted, Jerry Robinson-illustrated stories from just a short time later is to glimpse the ur-text of Batman comics. The gothic atmosphere. The long shadows. The wild splash pages. The comics of that era were not always well written, but you can understand why an artist — especially a young artist — would want to make comics. You had to work fast, but you could play with design and utilize different styles. You were forced to be productive. You can feel that energy in those pages decades later, like the ink had as much caffeine and uppers as was in their bloodstream for those nonstop drawing sessions.

I first learned about Mort Meskin reading the letter columns of Starman. Meskin drew some Starman comics back in the day, and he drew a lot of Vigilante — a character that Robinson and Tony Salmons revived for a miniseries in 1995-1996 — but he’s best known for Johnny Quick. A character I knew because he appeared in The Flash and who spoke a formula which made him super fast. Which doesn’t make any sense. But a lot of old comics (and current comics) don’t make much sense.

Meskin didn’t draw Quick the way that the Flash and other speedsters had been drawn, with lines behind them to give the impression of moving at a fast clip. Instead, Meskin would draw the character in multiple poses. An impression of speed owing more to Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2” than to other comics. That’s what made those old comics so visually interesting. These artists knew modernist art, grew up attending museums and studying at art leagues, they watched expressionist films, they studied the cinematography in Orson Welles and John Ford pictures, and they sought to pull all these influences into their comics. They were interested in light and design more than story, and if you read the stories, who could blame them.

I think of those pages of Johnny Quick performing multiple tasks, a single image capturing multiple moments in time, in the context of James Robinson’s work. Tying together all these disparate characters named Starman. Pulling together other characters, from The Black Pirate and The Shade, the Elongated Man and Black Condor, Phantom Lady and Scalphunter, Balloon Buster and Solomon Grundy, Sandman and Rag Doll. All of these ideas and tones and approaches, from the goofy to the deadly serious, existing together and making up a cohesive whole.

***

Starman debuted in 1994 and over the years it has often been compared to the Image Comics of the era. The bad Image Comics, or rather, the best of Image Comics, which emphasized style over substance and focused on the art to the exclusion of the writing, which tended to be poor. Not unlike those old Golden Age comics. Today comics are generally defined by writers, who are now seen as the primary “author” and dominant voice of the comic. I say this as a writer, but arguably the best comics — the purest comics, if you will, from classic Archie Comics, old superhero tales you can read without pausing to linger over the word balloons, the initial runs of Spawn and WildCATS and Cyberforce — are all defined and shaped by the artists.

Starman was, unlike those Image comics, a book defined by the writer. A novelistic approach to comics, with a beginning, middle and ending. It is an approach to comics that has become more commonplace in the years since, but at the time it stood out as something unique. There were series that were defined by the writer’s sensibilities before and after, but they tended to be unusual. They were also written about repeatedly because they appealed to other writers and people trained in literary studies.

The nature of the writing in Starman is important. Comics has a complicated relationship with their history and legacy and in the decade after Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC was interested in how to pass the torch and handle the legacy of their older characters. They did so in a variety of ways that ranged from Hawkworld to The Spectre to Supergirl. Barry Allen died and so Kid Flash/Wally West became The Flash. In the hands of Mark Waid, the cast of the book grew to include multiple generations of characters. There was a Batman family that expanded. Some characters were established as being older, with stories that existed in the past that could be mined, and play a supporting role in newer stories. A new Supergirl was created from scratch. Hal Jordan went crazy and became a villain and Kyle Raynor became the new Green Lantern. His girlfriend ended up in a refrigerator. The response to that by some fans was to create a club called H.E.A.T. and send death threats to the creators. The sales of GL comics went up, but this must have impacted DC when it came to making changes.

It was in this context that Robinson made a book that was not about the previous Starman, Will Payton, whose comic ran for 45 issues, from 1988-1992, before the character was “killed” in the miniseries Eclipse: The Darkness Within. It was a comic that was not about Ted Knight, the Golden Age Starman. It features the death of Ted’s son David, the new Starman, in the opening scene. It’s easy to say that Starman was a character few people cared about or that Robinson did it really well– both of which are true– but these choices were likely scrutinized at the time, even if not publicly.

***

I have never read the Douglas Coupland novel Generation X, which became the name to those born between 1965 and 1980. I know many of the other Gen X texts that helped to define the culture and the era. While he was a timeless archetype in so ways, Jack Knight emerged out of that era.

The film Slacker stands out in my mind as defining the era more than any other work. The term was co-opted and reused in different ways, but in its original meaning, the reason why Richard Linklater named his 1991 film that, is one that Jack would have appreciated. Jack would have been one of those characters, engaged in a deep, passionate conversation about something of no real importance, but deeply meaningful to them. Of course most of the characters in Slacker were engaged in doing very little (“I may live badly, but at least I don't have to work to do it,” said one character in the film) and Jack is far too busy to be a slacker. That’s before he became a superhero.

In retrospect, the obvious analogue for Jack is Rob from Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity, although the novel wasn’t published until 1995 and the film version starring John Cusack came out in 2000. Looking back on the character, reading old letter columns, that’s who I think of. For both Jack Knight and James Robinson, I suppose. It’s easy with the benefit of hindsight to call Rob and Jack otaku.

Not in the original meaning of the word in Japanese, but the term as it has come to be known. Of being a learned expert in a subject. A particular kind of topic. We don’t talk about professors as being otaku. That's a term reserved for junk dealers and record store owners, bookstore employees and zine makers, old website designers and copy shop workers, who can talk at length about forgotten television shows, old comics, obscure crime novels, underground films. The kinds of thing you couldn’t write a paper on at school. The kind of thing that wasn’t written about in newspapers. This was learned about and shared through conversation. Information and knowledge that wasn’t accessible and had to be cobbled together from different sources.

I can’t speak to Robinson. I won’t say that he wrote the character as himself, but in the way that many artists have drawn characters to resemble themselves — that way they could use a mirror to get a reference image — the obsessions and interests of writers often seep in whether intentional or otherwise.

That can be deceiving. Robinson may be interested in collecting and make Jack a dealer with a deep knowledge of such things, but just because the pop culture ephemera that is in Jack’s head came from Robinson’s pen doesn’t mean it has any relation to Robinson. In issue #15 a villain is monologuing about Raymond Chandler film adaptations, and it would be a mistake to see any of those opinions as Robinson’s. Though he clearly possesses a deep knowledge of the subject. This was the '90s and pop culture monologues were all the rage. Blame it on Tarantino. After Pulp Fiction came out in 1994, it was years before audiences and Hollywood tired of the derivative dialogue driven crime films of this era.

On the other hand, who would suggest that Hoagy Carmichael sings his songs better than anyone, including Ray Charles? Who remembers Julie Newmar’s nude scene in MacKenna’s Gold?

This was the era of the collector. VHS giving way to laserdiscs and then DVDs. People bought compact discs to update and replace their music collections. Sure, there were collectors before, but it was easier than ever. I won’t say the '90s were better. But we had stores. We left the house and we went out in public and we bought physical objects. Bookstores and music stores with new items. Used bookstores and second-hand shops and flea markets. Sometimes we read in the store without buying anything, and sometimes we shoplifted. There was something physical about life back then which allowed for us to discover writers and artists by accident.

The collector, the obsessive, the otaku, was a defining figure of Gen X. More than the slacker, I would argue. Because in those pre-internet or nascent internet days, finding things, learning things, took work. We believed that the truth was out there. This was how so much of the internet was built. Message boards and fan sites and people trading information and sharing knowledge. In the days before music and movies could be downloaded and shared online, people were accumulating physical media and sharing it. Desktop printing and copy shops fueled the zine boom.

These works were available but they were hard to find. You had to know someone. Stumble across the right store at the right time. Catch it on television when it aired at an odd hour. Answer an ad. This was how we bought and rented and borrowed comics and movies and TV shows. We didn’t have wikipedia or Shazam. We set the VCR to record shows broadcast in the middle of the night. We transcribed song lyrics listening to the radio. We listened as people, some patient some not, explained books or movies to us giving us a context we never would have known. Learning about books and shows and films long before we would ever have a chance to watch or read them. When there was no guarantee that we would even get a chance to read or watch them. This is when I began my lifelong habit of making lists.

I always felt like I didn’t know enough back then and was always frustrated that I didn’t know more. I feel the same way now. It was just different back then. As L.P. Hartley put it, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.”

***

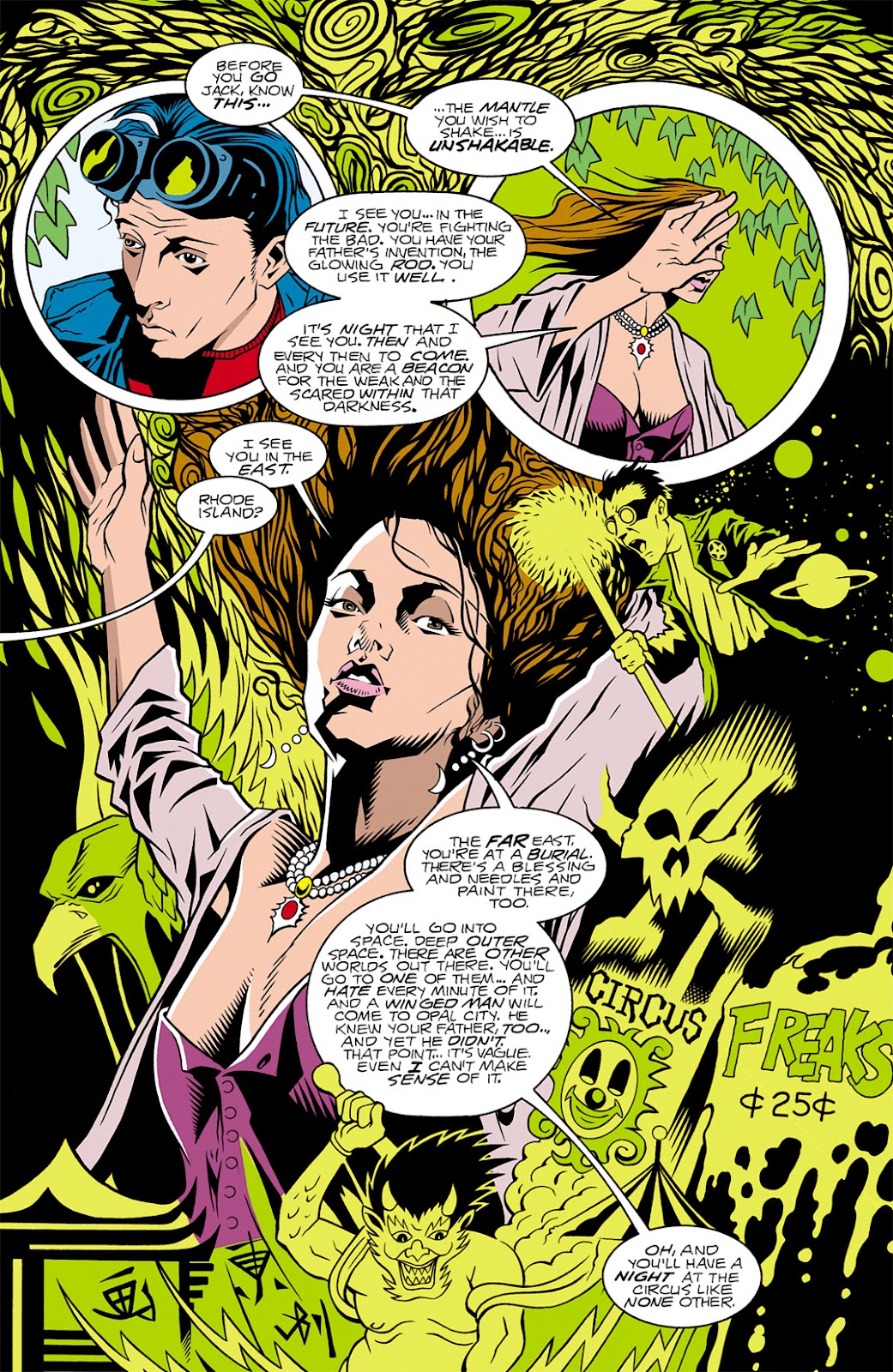

In issue #2, Jack meets Charity, who opened a storefront, "Fortunes and Forbidden Tales” near his shop. Charity has “the sight”, and in a splash page she predicts some of Jack’s future. A sign that Robinson had a plan for the series from the beginning. In fiction, as in life, I have little use for psychics. I don’t remember how much it annoyed me back then. I’m sure I rolled my eyes at it, but I can’t say whether it grated.

I find it annoying in fiction, but the U.S. has always had a deep prophetic tradition, with a parallel tradition that includes everything from the Fox sisters to Ouija boards. My thoughts on religion are complicated. My people have been in North America for a long time, by the standards of white folk. Whatever my feelings about the Puritans, the Transcendentalists, the Romantics, the Enlightenment, the English Civil War and the Restoration, the First and Second Great Awakenings, the state of Connecticut having a state-sponsored religion until 1818, the anti-Semitism of Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformation, the Thirty Years War — to say nothing of the socio-political positions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, the Protestant sect in which I was brought up — the truth is that Scooby-Doo, a show about uncovering the truth and how superstition is weaponized and actively used to obscure the truth, is more reflective of my day-to-day beliefs.

Of course prophecy and the supernatural has been a part of American literature and stories about the Americas since the beginning.

Rereading Starman I thought of Corto Maltese, another series where fate plays a role. Corto slicing his hand with a razor to form his own fate line on his palm. I also find such talk in Hugo Pratt’s hands an eye-rolling distraction from the plot as characters ramble for large blocks of text, but it gives me a chance to spend the time with Pratt’s linework.

Prophecy and destiny and ordered systems. Are these the ingredients of novels and narrative works? A way to make clear that there is a structure and lay it out for the reader in a way that’s easy, but also effective? A trailer, offering a glimpse of what’s to come? A tease saying, you may be on the fence, but we know where we’re going?

The United States is all about money and religion. Bob Dylan sang, “it may be the devil or it may the lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody,” but what’s striking if you read enough history and watch the news, is how many people are all about both. These colonies were all about what could be grown and what could be taken. The Portuguese fishing the Grand Banks before Columbus set sail, keeping that knowledge to themselves. Timber. The fur trade. That’s how they attracted settlers, promising them wealth and possibility. Immigrants of the 19th century sang that there were no cats in America and the streets were paved with cheese. It’s hard to fault the poor for wanting a better life, but for centuries, the Americas have been a money-making enterprise.

In order to make it palatable — to make it noble — we don’t say that, because talking about money is gauche. According to people who have money. My Puritan forefathers believed in Calvinist doctrine of pre-destination, that their wealth and success was a sign of their goodness. Thus the accumulation of wealth became a spiritual practice. In other words, God is like the writer and everything is laid out and planned. Though Robinson and other comics writers might point out that things are rarely as plotted out in advance as they might seem. Which is why the next time Charity reads Jack’s future, it’s changed a little. Is the fault in the stars or in what DC would let Robinson do?

***

Opal City is located in Maryland. As established in JLA #115, apparently. I learned this fact writing this article. It feels too real for this fictional city. Like the way that Tony Harris drew the Altoids container that Dudley Donovan carries with him in issue #30. Just a little too sharp and detailed that it unbalances the image and the page.

Opal is an old city settled by Europeans, with proximity to the Caribbean, and a site for Nazi sabotage, so it’s obviously an East Coast city. A unique coastal town – Savannah and Charleston come to mind. But in the North. Not just because no one spoke with an accent. Delaware is too boring, so I suppose it has to be Maryland. I know that there are people who like this level of detail. I’m just not one of them. I’m happy with fictional cities existing in fictional spaces.

Genre stories, even the dark ones, require a lightness. They rely on cliches. Upending some even as they wallow in others. Part of what makes it a genre story is that it’s not quite real. No one wants to read a thriller where every character is drawn with this intense deep level of realism. You can’t enjoy the puzzle or the rollercoaster ride if you’re riding a brutal wave of how the characters are being traumatized. Robinson understood that. Opal City is not real. It does not exist in a specific state. It’s an idea. The United States in microcosm. There are Puritans and pirates, nazi saboteurs, spree killers and bank robbers, canyons and prairies. The geography is not that of a real place.

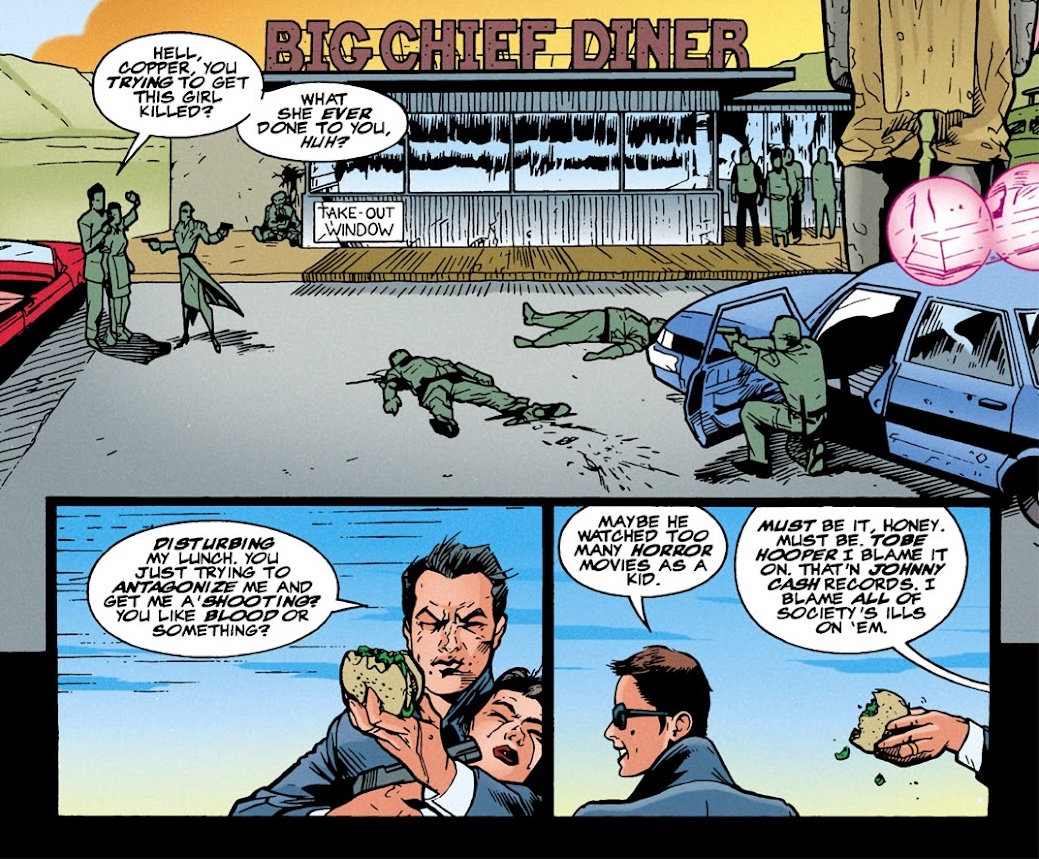

In issue 36, a "Times Past" tale,1 we meet Will Payton, and Aaron and Lupe Bodine, spree killers making their way through a Western landscape. This is what I mean about Opal not being a real city, but a representative city. An American city. Reading that issue I was reminded of Wim Wenders’ Paris Texas and Don Siegel’s Charley Varrick. It treats the landscape as something to linger over, just as the cityscapes are important when the story is set in Opal. Consider the handful of stories involving the Prairie Witch, who robs banks in Opal and nearby Turk County. Her name alone makes her sound like a comic book villain, possessing this mix of science and magic. Bank robbers of the 1930s is something I always associate with the Midwest. The landscape and backdrop of John Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde or Pretty Boy Floyd. Max Allan Collins tied the bank robbers to the mobsters of that era in a way that I think Robinson, based on how he wrote Vigilante, would likely agree with in many respects.

This is what I meant when I wrote that Starman was about the United States. It’s all wrapped up in the story, but if you start setting it in Maryland, or caring where in Maryland the city is located, it falls apart.

***

The second page of issue 1 has a literary reference so subtle that most readers may not have noticed. I don’t know that I registered it when I first read it. I likely hadn’t read Browning then, but on rereading, it made me smile. A few minutes into rereading and I thought to myself, there is a reason why I loved this comic. Both the reference itself and the subtlety.

Has there ever been a more literary comic than Starman? The only one close is Sandman, and as a fan and a reader, I often rolled my eyes at how describing it as literary was like punctuation, but Sandman often wore its influences on its sleeves, in a way that could be almost begging for attention.

Starman had Oscar Wilde and Charles Dickens appear in its pages, and had them influence and be influenced by the characters in the series. The Picture of Dorian Gray is the Wilde work that almost everyone knows, but consider how deep Robinson knows Dickens. The Shade — or rather, before he became the Shade — was the basis of Dick Swiveller in The Old Curiosity Shop. The Shade also notes at one point that Dickens tried to write a novel about him but abandoned it, taking elements to write another tale. Which I can only assume is a reference to The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain.

Many people have talked about the ways that Robinson engaged with DC characters and brought them into the narrative — most of the characters I didn't know anything about and had no idea that they existed before Starman. This was the '90s and I didn’t know much about comics and certainly not enough to know whether the characters being introduced were ones that had existed in a few dozen of DC stories in the past (Brian Savage, Jon Valor) or new one that was created for the series (Hamilton Drew, Jake “Bobo” Benetti). The internet had escaped DARPA and research labs to screech through phone lines, but Netscape Navigator was only released in 1994. We didn’t have information at our fingertips in this same way. Unlike today, there were no wikis to learn what comics Sierra Smith appeared in before Starman.

It’s clear that this was a comic written by someone who had read widely and deeply. From the references to Browning and Blake, the discussion of Seth Morgan’s Homeboy, which has become a classic in the far future. There’s Jack’s Henry Miller and Anais Nin joke to Nash in issue #16, which I know I didn’t understand at the time (I was naive as a teenager, and I read both authors before I ever did most of what they wrote about) but it made me laugh out loud on rereading.

There’s the exchange about people’s favorite Woody Allen movies. Something that we regularly did in the '90s before all the scandals, when he was making good movies. Jason Woodrue talking about how he thinks Interiors is a funny film made me laugh out loud. There are a host of other little moments like that throughout. Like Robinson naming the visionary genius/madman who designed the rocket that Jack and Mikaal go to space in “Herman Moll” after the legendary British mapmaker and cartographer.

Some will say I’m overthinking this, but in my line of sight are my nonfiction book shelves and in the Bs there are books about comics by Bart Beatty and Scott Bukatman, but I have books on other subjects by John Berger and Peter Bogdanovich, Jacques Barzun and J.A. Baker, Joseph Brodsky and Rick Bass, Lisa Birnbaum and Ian Buruma, Joshua Bennett and James Baldwin, Wendell Berry and Peter Brooks, Walter Benjamin and Ned Blackhawk, Kathleen Belew and Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Lary Bloom and Robert Brigham, David Blight and Bernard Bailyn, Mary Beard and Andrew Bacevich, Jennifer Baumgardner and ... my point is that I see all of these deeply disparate authors and subjects and approaches as being in conversation with each other about history and art and life. I’m not saying that Robinson read some or even any of these books, but he was shaped by an eclectic and deeply personal list of influences outside of comics that influenced his writing of the series.

For all the attention lavished on Robinson as someone who was able to incorporate so much comic book lore into the series, he was also able to take his own interests and incorporate this into Jack Knight’s personality and thoughts. Like a cultural magpie, Robinson was also drawing from literature (high and low literature, if that means anything and if you care) and managed to incorporate all of that into the very text of Starman. It wasn’t simply a question of the narration, but in Jack’s thoughts, in the fabric of the story. If you’ve read Dickens and Wilde, I won’t say that the comic makes more sense, but it feels like a part of the world. Other comics writers may make literary references or have characters talk about books, but few of them have ever been so influenced by literature, and made it a part of the comic, the way that Robinson did.

***

Rereading the series, I kept coming back to the late, great filmmaker Nicolas Roeg, who I think might be Robinson’s biggest influence.

I love Roeg’s films, which I first discovered in the '90s when Walkabout was rereleased, a film whose images have haunted me since. That led me to his other work: Performance, Don’t Look Now, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Bad Timing, Eureka. Between 1970 and 1983, he directed or co-directed six films, and while they had mixed critical and commercial reception at the time, I would argue that all of them are great.

One of the things that made Roeg great was his use of disjointed editing. A Roeg film doesn’t have a narrative told in a chronological fashion. It’s not simply told out of order like Pulp Fiction or a crime film where we learn that there was a whole other story happening parallel to the story we’ve seen in a way that makes us rethink how it all fits together. Roeg took all of that one step further. He showed us scenes that hung together, jump ahead in time, jump into the past, spend time with details and characters that seem irrelevant or at least insignificant, only to learn later that those details were vital to understanding what followed. He would sometimes reveal the how or why of a story later on, in a way that made us rethink what we had been watching.

Part of this was to make the viewer to actively understand and piece together what they’re seeing. You become a detective trying to tease out the threads and details and motives, understand not just how it all fits together, but why. And why it’s organized in this manner, which is more precise and calculated than it might initially seem. Bad Timing, for example, opens with a woman being brought to a hospital having attempted suicide and the film is an investigation and a series of flashbacks detailing what happened and why. The film ends where it began, but the viewer understands the events in a very different way, noticing things that we didn’t the first time around.

People might think about a story line like “Sins of the Child,” which is told in a fractured manner, but a Roeg tale is more complex than that. I would argue that the entire series shows the influence of Roeg’s work. Think about all those "Times Past" tales and one-off stories, but become part of the very fabric of the finale and the book as a whole. The construction of Opal City and the architecture, Jon Valor and his curse, Etrigan foiling Nazi saboteurs, and how all these disparate, seemingly unconnected one-off stories come together in Grand Guignol storyline. Consider how Brian Savage's life and death is presented over the course of the book. Look at the ways that The Shade’s origin and backstory are addressed. Almost every element in the book has a deeper meaning and significance than it did at first glance. It requires rereading to really understand and appreciate the book and its construction.

It’s hard enough writing a monthly comic where each issue is impressive and unique and feeds into a larger storyline. I’m not saying that what Robinson did is unprecedented. Comics creators have seen the value in seeding story and character ideas that pay off months or even years down the road. Or get paid off later when another creator has taken over and notices the hanging plot threads. I would argue that Robinson and his collaborators were able to craft something unique. They built off what others had done and crafted something new that could stand on its own. There have been self-contained graphic novels and miniseries and maxi-series that have done what Robinson did in Starman in terms of structure, but in a monthly comic — to say nothing of the challenge of writing a monthly comic for seven years for one of the big two where there were editorial whims to address and work with constantly — I’ve never read anyone who has tried to do this in such a subtle and complex way as can be found in Starman.

I am admittedly someone who loves to obsess over narrative structure. Starman’s structure is complex in a way that very few comics have ever approached, before or since. Not superhero comics, but any comic. No “mystery box” nonsense. By the end of the series, all these threads come together organically and beautifully.

***

The post We are all in the gutter: <i>Starman</i> at 30, part 1 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment