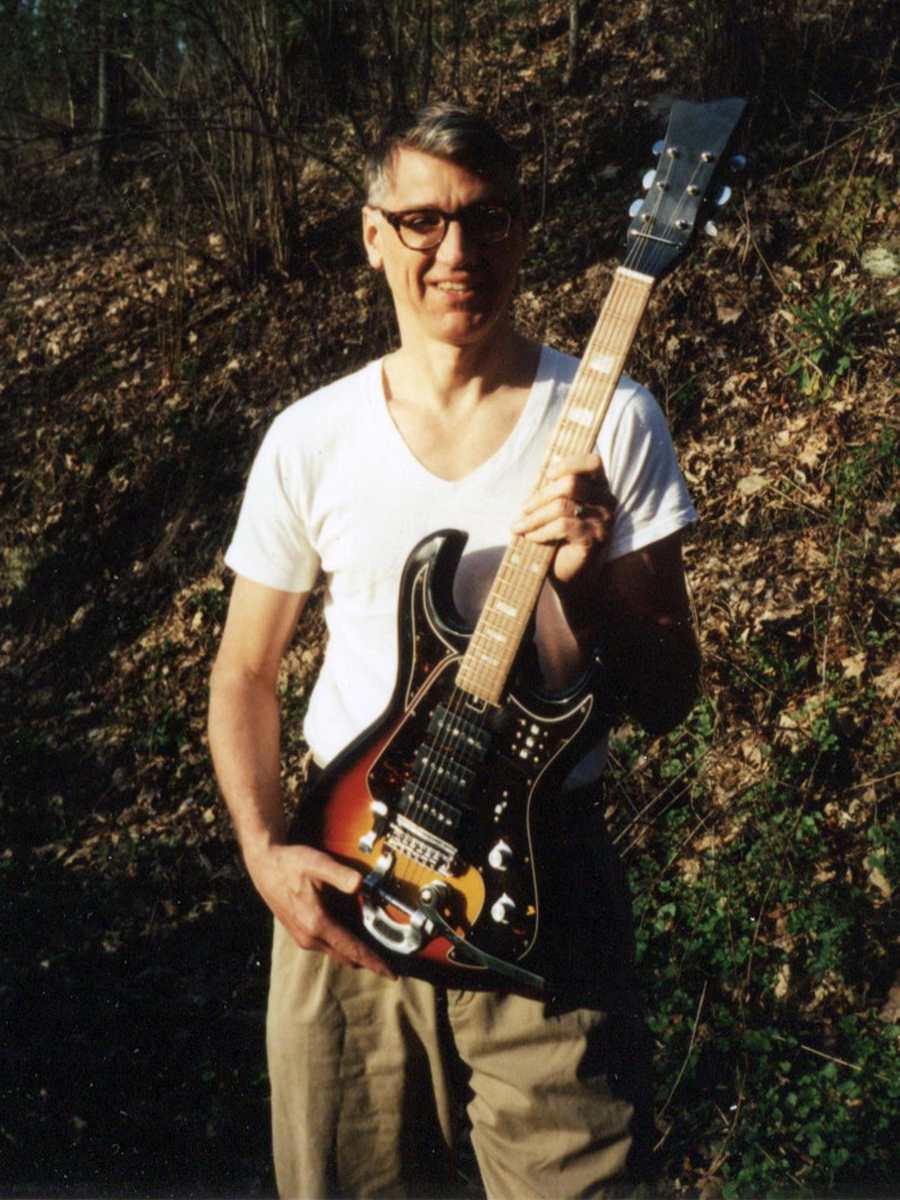

J.D. King, a prolific cartoonist whose stylized, jazz-infused illustrations appeared in many magazines in the 1990s, died at his home in Remsen, New York in early November, 2025. He was 74 years old. There is no exact cause of death but also no cause for suspicion. According to several people close to him, King was in good health and regularly rode his bicycle and did pushups daily. A long-time friend who spoke to him shortly before his death said that King had been saying that he was experiencing flu-like symptoms.

"It might have been the flu–people don't take it seriously, but the flu can kill you," said his brother, Peter King of Manhattan. "It might have been the flu, or maybe it was Covid and he thought he had the flu. Who knows? Other than being dead, he was in perfect health."

"The cause of his death is a mystery," said his ex-wife Sally Eckhoff. "The funeral director said, 'We don't know, but in any case it must have been quick,' because he was found in his bedclothes. He was always in his PJs [when going to bed]–he always was very well dressed. But the cause of death is...we don't know. But it was probably something like a heart attack or a stroke or an aneurysm. And...it mystified everybody because he looked so fabulously healthy."

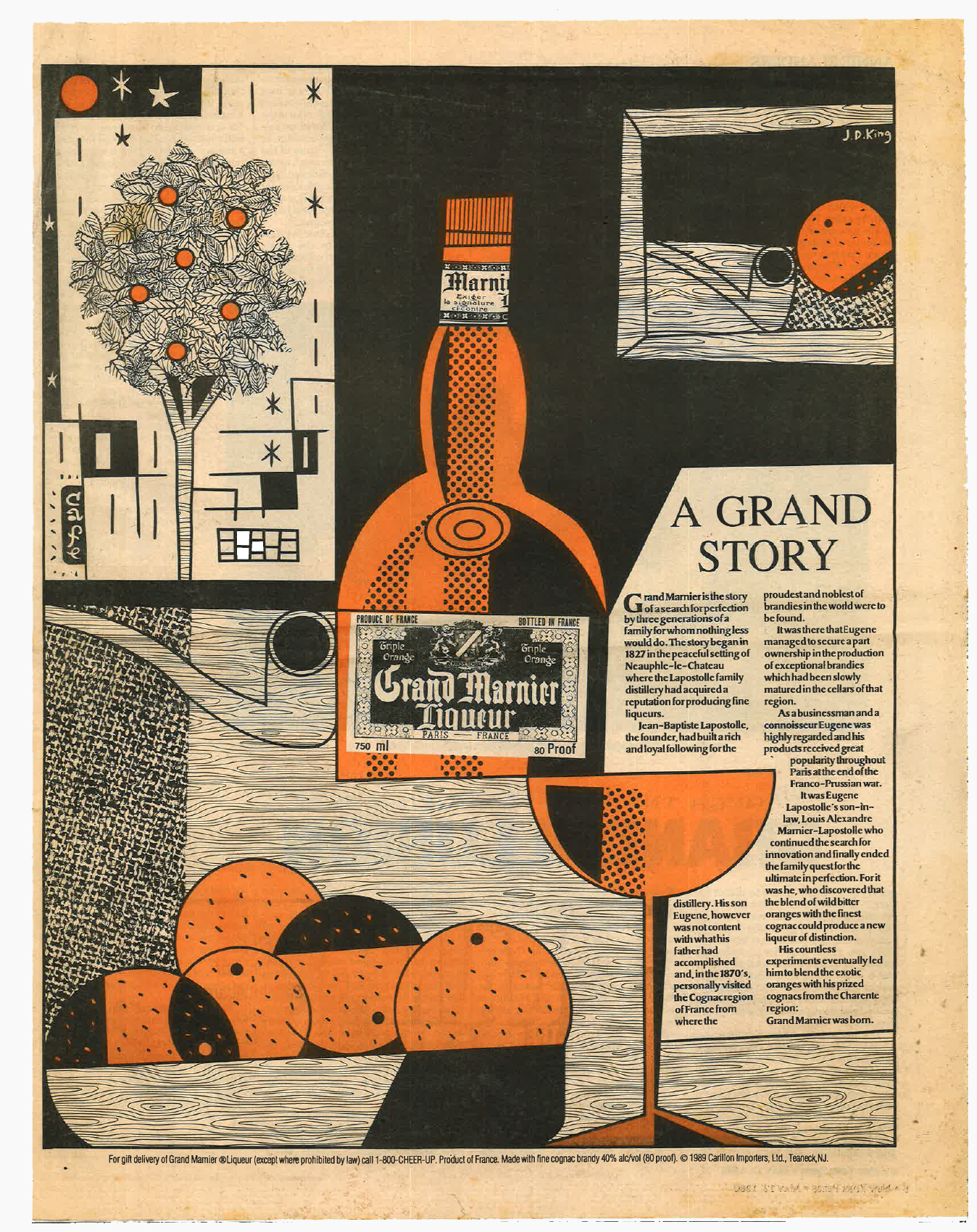

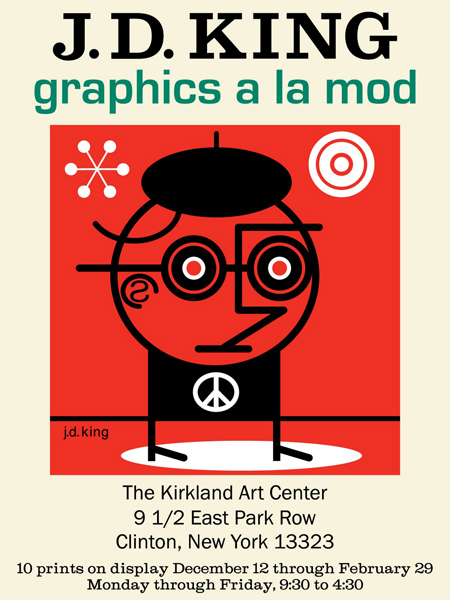

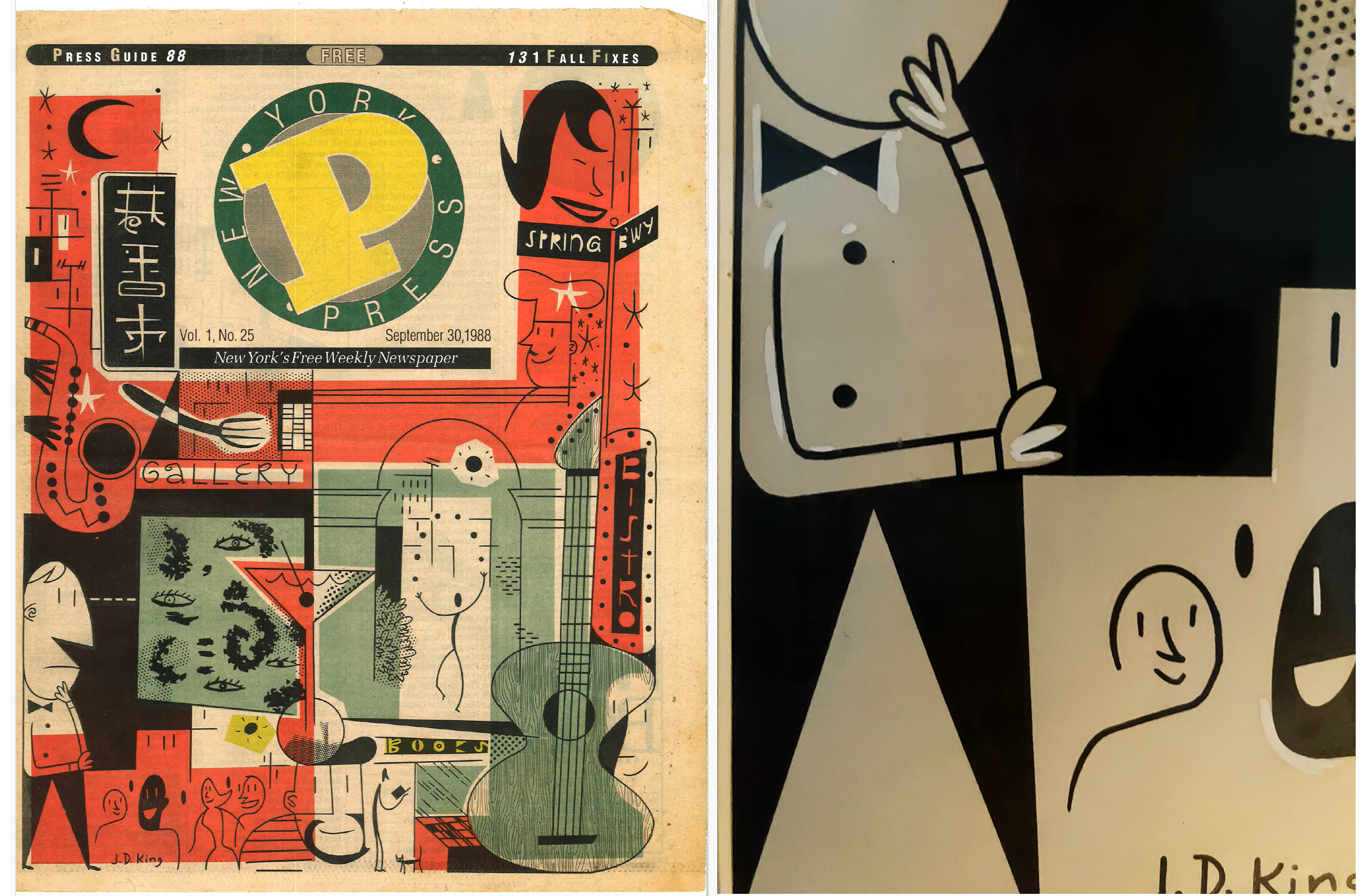

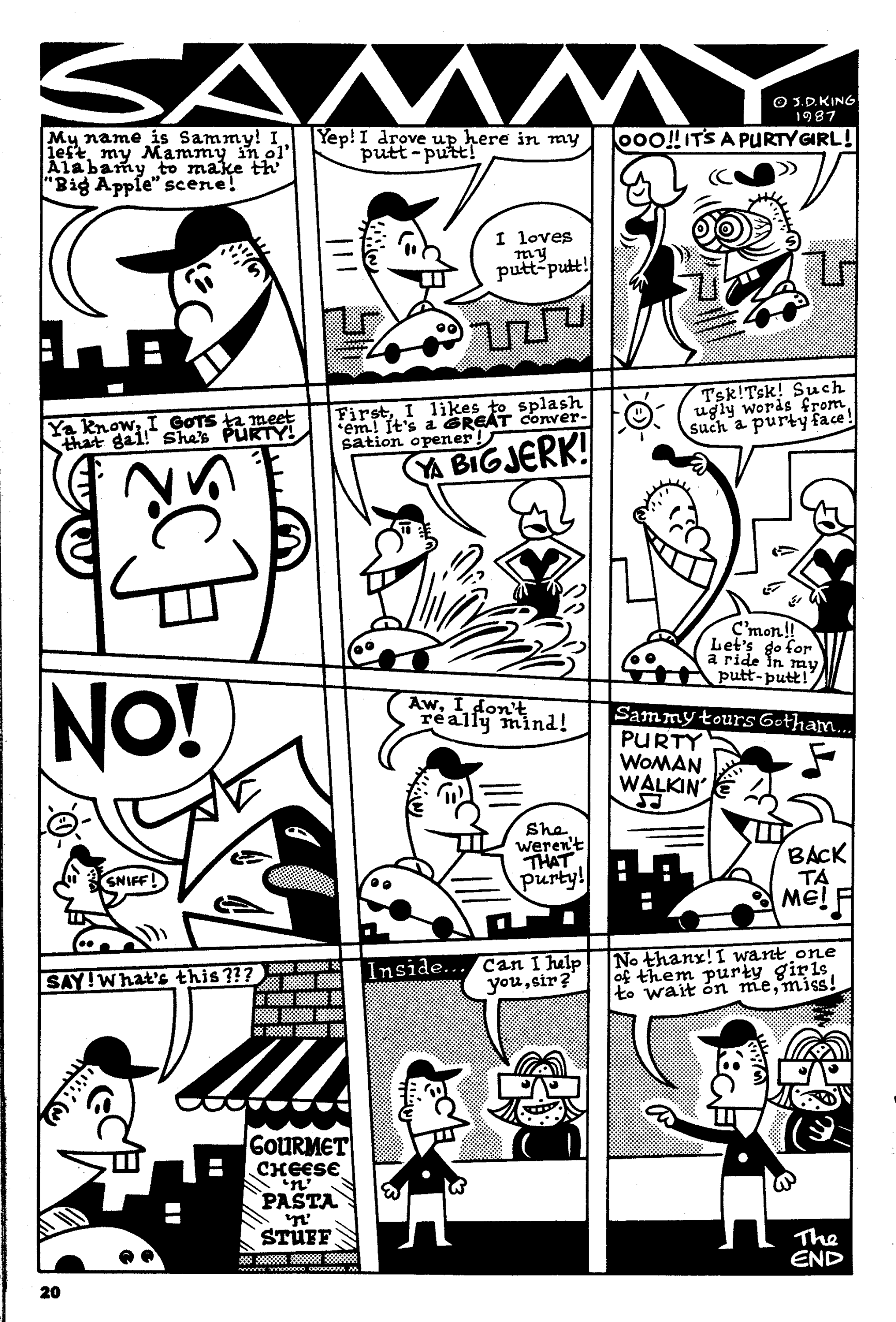

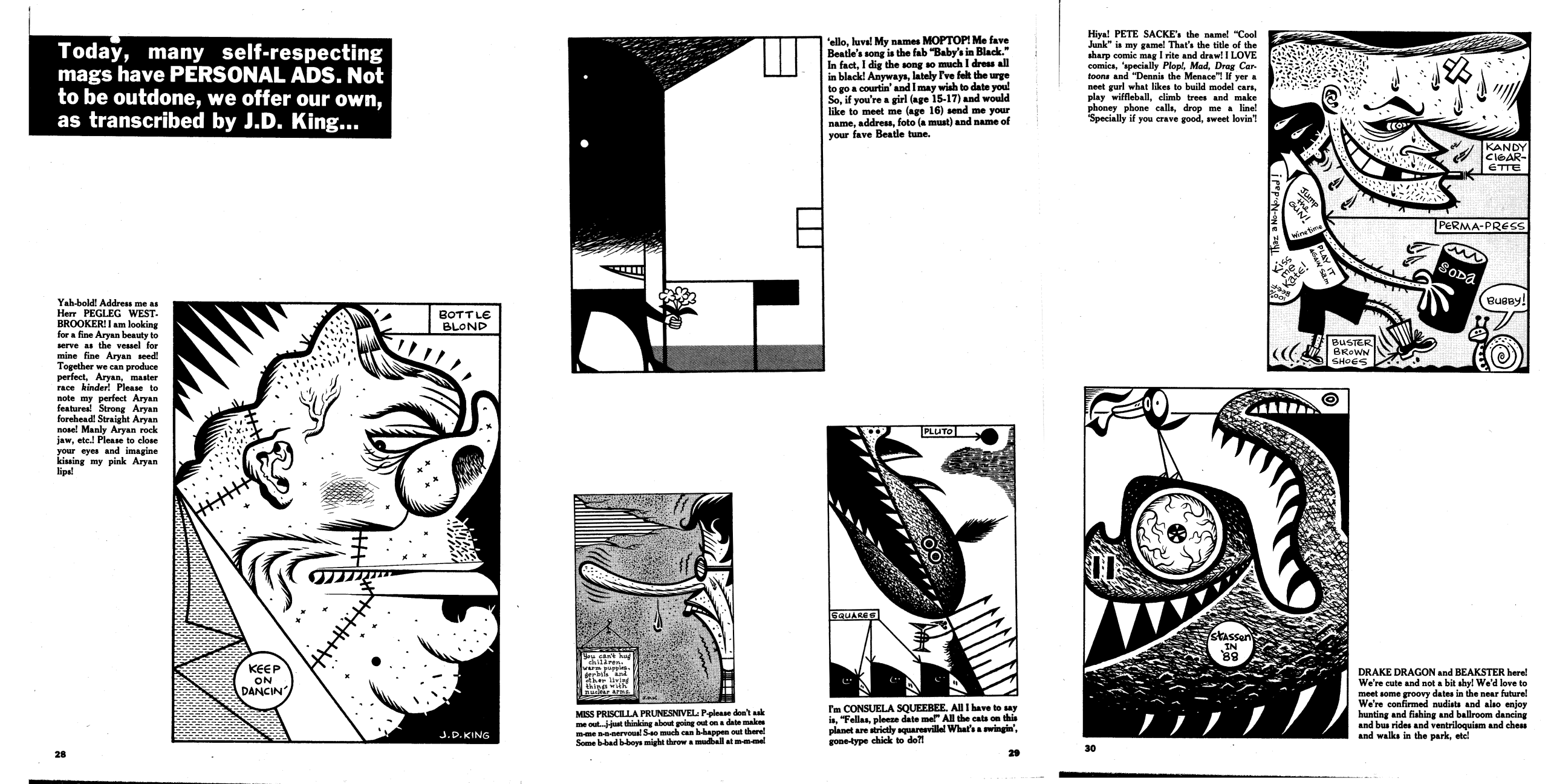

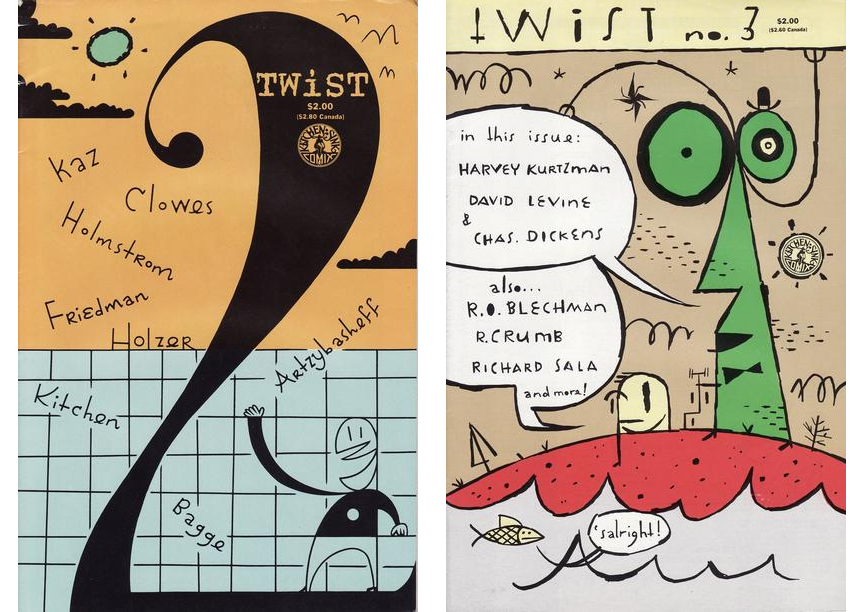

Whatever the actual cause of death, his passing also begs this question among some members of the comics world: "Whatever happened to him?" During the 1980s, '90s and into the 2000s, King was a familiar presence in the NYC alternative comics scene and a highly successful illustrator. His comics appeared in several issues of Weirdo, he edited the great anthology Twist for Kitchen Sink, he did covers of the New York Press, Screw, and other alternatives and his illustrations were everywhere–The New Yorker, The New York Times, Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, Adweek, Time and countless others.

Then...poof. He seemed to have just vanished.

Like some, I had heard that he had left New York City at some point in the 1990s and was living...somewhere in Upstate New York. There had been several times over the years when I had wanted to reach him for some story I was working on, but I had no contact info and neither did anyone else I had asked.

I wish I had tried harder.

****

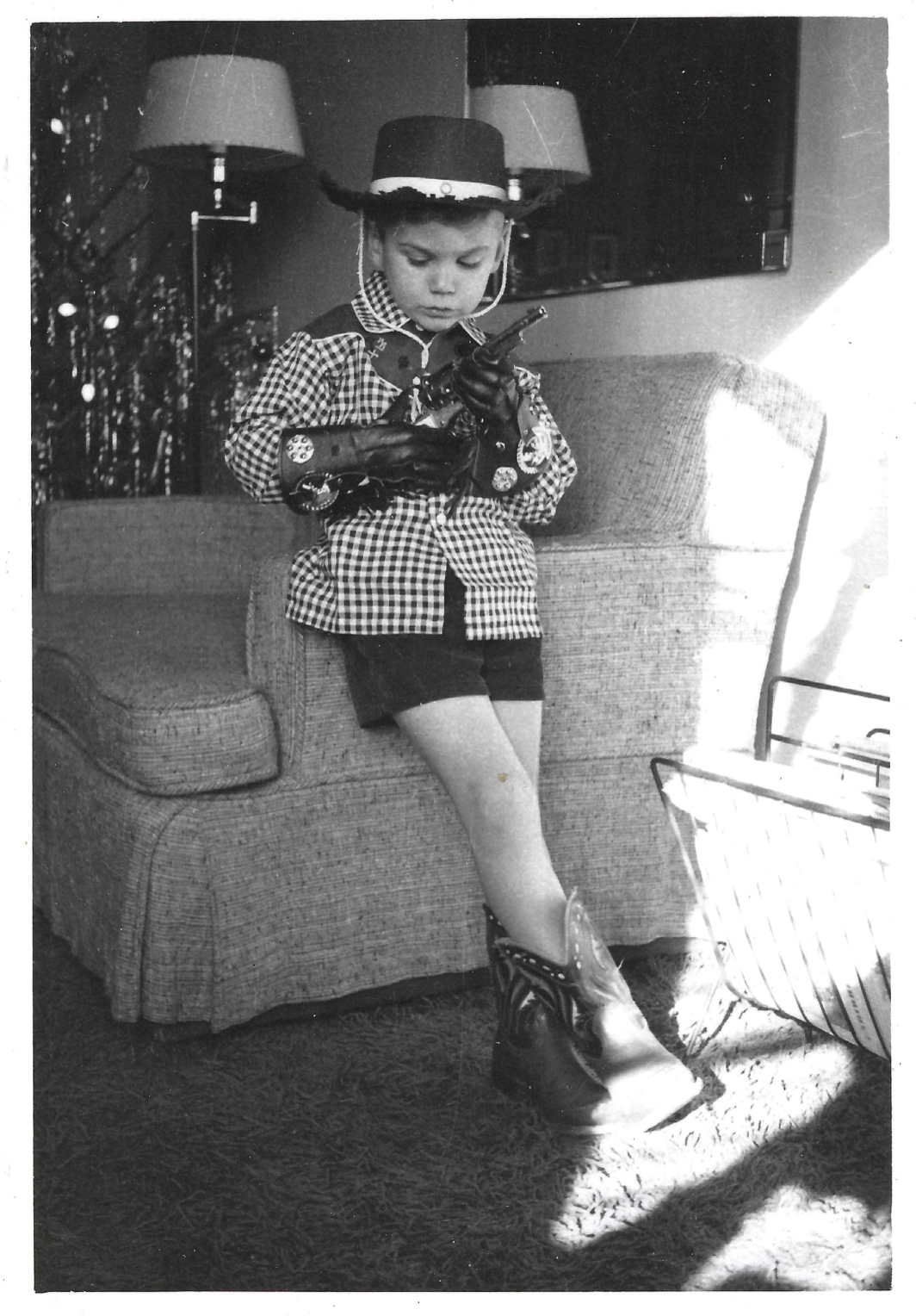

John David King was born on May 3, 1951 at Doctors Hospital in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. His father, George, was an executive with the Aetna insurance company and his mother, Eleanor, was a Vista worker who later worked at local schools. At the time of King's birth, the family lived in Hell's Kitchen and later settled in Middletown, Connecticut.

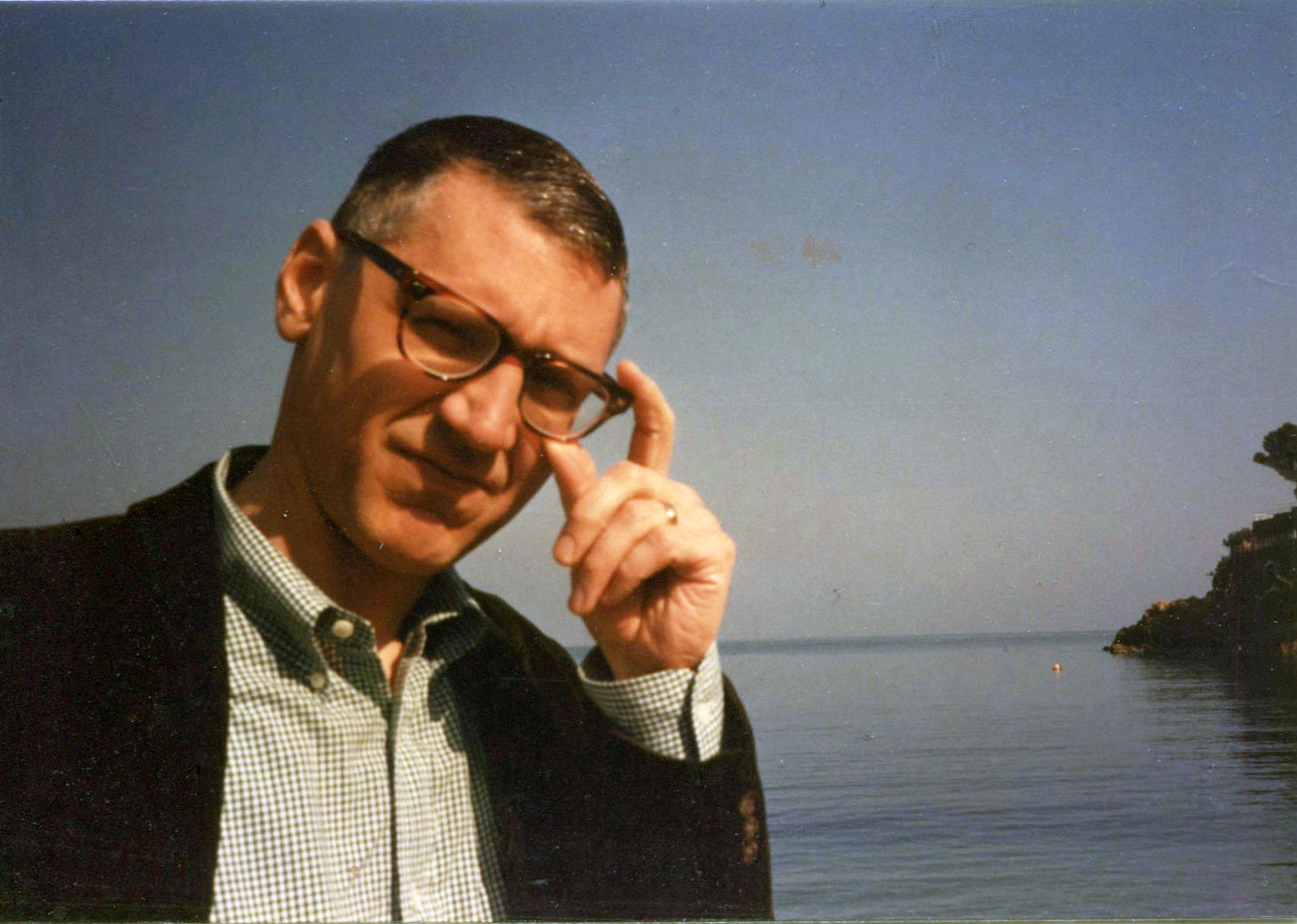

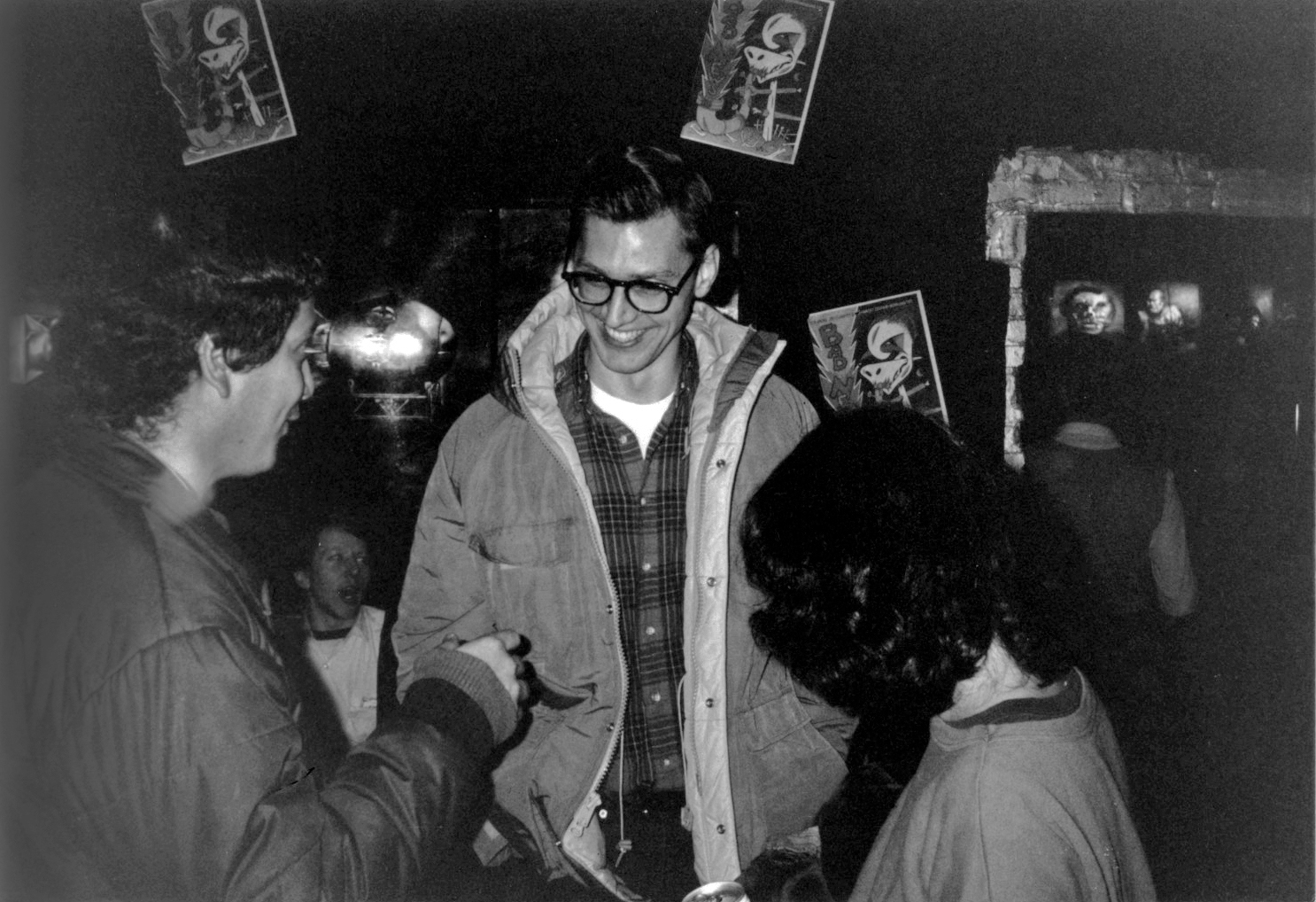

King was a tall man, standing 6' 4", and was almost always the best-dressed person at any event he attended.

"His style was pure Brooks Brothers," said his first wife, Jane Brettschneider. "I think that if Brooks Brothers carried diapers, he would have worn them as a baby."

"I'm one of three people in the world who called him John," said his brother Peter King, who is five years younger. "Besides his middle initial, I suppose the J.D. was an homage to J.D. Salinger...and Juvenile Delinquent, because my brother also liked those sleazy movies from the early 1960s. We performed a play for my parents when I was age 5, and it had to do with switchblades and going to a rumble, so by age 10 he was really enamored with juvenile delinquents."

Growing up, King "drew all the time," and also "took advantage of being the older brother," said Peter King.

"He used to torture me all the time," he said, laughing. "He never wanted me in his room, but when I was around four or five years old, he said, 'Come in. I'm going to draw your portrait.' So I was sitting in a chair and he was there with his pad, and looking over it and drawing very carefully–he's like, 'Don't move!' It was probably four or five minutes, but it seemed like forever. Then he turned it around and it was a drawing of Frankenstein. (Laughs). And I got really mad. And of course, four months later, he said the same thing–'I want to draw your portrait.' And I said, 'You're not going to make me Frankenstein, are you?' 'No, no.' And of course he would. I can't tell you how many time I fell for it."

In 1971, King left to attend Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, Rhode Island and it was there that he decided he wanted to be a comics artist.

"[Before RISD], I liked comics," he told the comics historian Jon B. Cooke in a 2019 interview. "I liked the undergrounds, Crumb, all that kind of stuff. I liked the San Francisco posters. I liked Pop Art, Art, Nouveau, Surrealism, Dali, stuff like that. All the kinds of stuff that a high school kid would like in the sixties. But it wasn't until I moved to Providence and sat around smoking dope one evening with some friends, and somebody handed me that Les Daniels book, [Comix: A History of of Comic Books in America] and it had that Wally Wood strip from Vampirella [#9, "The Curse,"] and I started reading it. I was like, whoa. Really? That's when I decided I didn't want to be an illustrator. I didn't want to be a painter. I wanted to do comics."

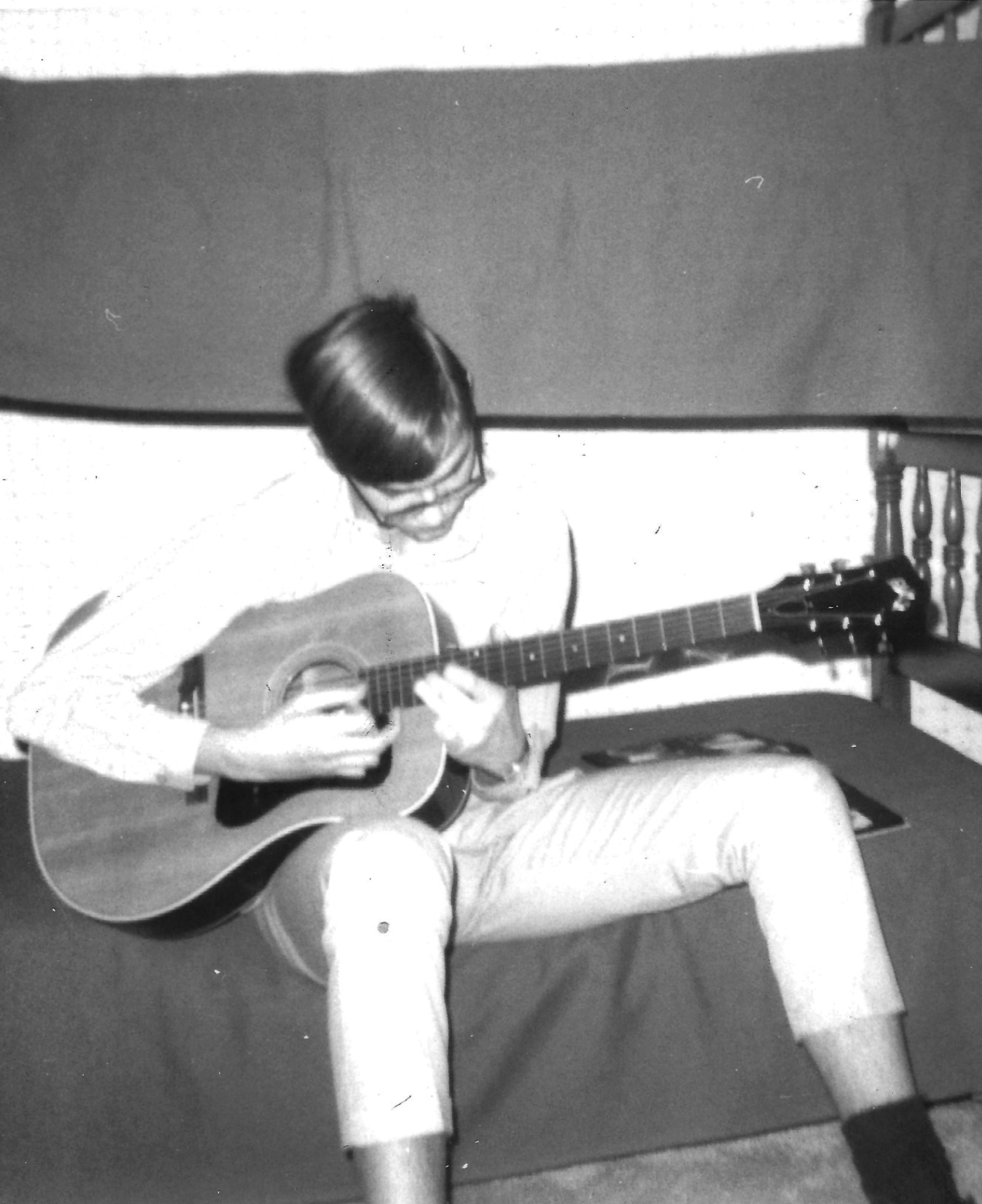

At RISD, he met up with other aspiring artists, including future members of the band Talking Heads–David Byrne and Tina Weymouth–and the cartoonist Gary Leib. Like those three, King was also a musician, and a chance encounter in a Connecticut record shop a few years later would later become a footnote in rock history.

"I would have been two years out of high school, living with my parents in Connecticut, and just going back and forth to New York," said future Sonic Youth frontman Thurston Moore, who used to buy his Dammed and Sex Pistols records at Cutler's Records in New Haven. "And one day I went up the the 'V' section of the records, to the Velvet Underground placard, and there was nothing in it. Nothing (laugh). And I saw this kind of Buddy Holly-looking guy just staring at it, like almost forlornly. And I said something like, 'It's looking pretty bad for Velvet Underground collectors,' and he just looked at me in surprise...and then he immediately said, 'Do you know where you can find copies of PUNK magazine?' He was so excited by PUNK magazine. And then he said that he and his friends were moving to New York to start a band and I said, 'Yeah, I've been trying to do that myself, but I don't know anybody..."

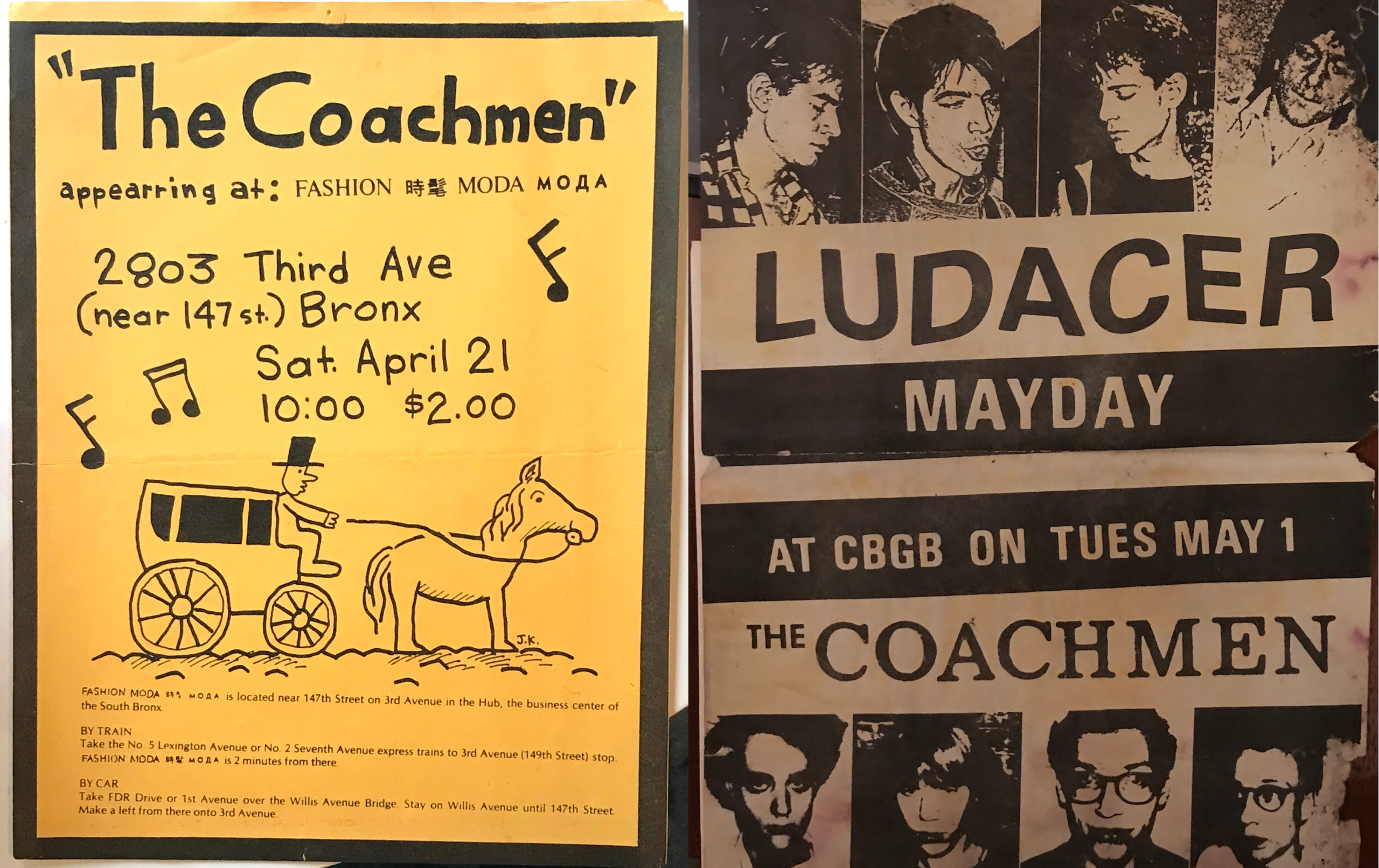

In the late 1970s, King moved into a building on South Street in downtown New York that was also occupied by other artists, including Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo and Kathryn Bigelow. Moore moved into the space himself, with his guitar and sleeping bag, and he and King formed the art rock band The Coachmen.

"When I moved to New York, I wanted to do either a band or comics," King told Cooke. "That was as close to what goal as I had. And I did the band."

In Nick Soulsby's 2017 book, We Sing A New Language: The Oral Discography Of Thurston Moore, King said: "Thurston was just a kid living in Bethel with no one to play with. He was bored, I remember him telling me that all anybody wanted to play there was Doobie Brothers songs. We were an outlet for him. He probably would have liked something more straight-ahead punk but it was still a band and we got to play out. Thurston would come down on weekends. I was 26, he was 19. At the beginning it was all these college guys, so it was cool having an official teenager."

"J.D. King was in a punk band with Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth in those days–The Coachmen," Peter Bagge told John McCoy in a 1992 interview. "I guess he had two loves, music and comics, and for too long a time he would put his artwork on the back burner while he was pursuing his rock and roll business. But by 1980 he was completely fed up. He was funny–he was always amazed that Thurston stuck with it, he just figured he was too unemployable to do anything else. But through sheer tenacity, by simply not being able to do anything else, Thurston ended up becoming a rock star with Sonic Youth [laughs]. But I remember when I met those guys with J. D. King, I thought they were going to go nowhere. But anyhow, that was a big inspiration, and it kind of gave everything a style–a feel, a style, and an attitude that we all shared, and really there was nothing contrived about that either–it was a sensibility that we all had to begin with that made Punk appeal to us."

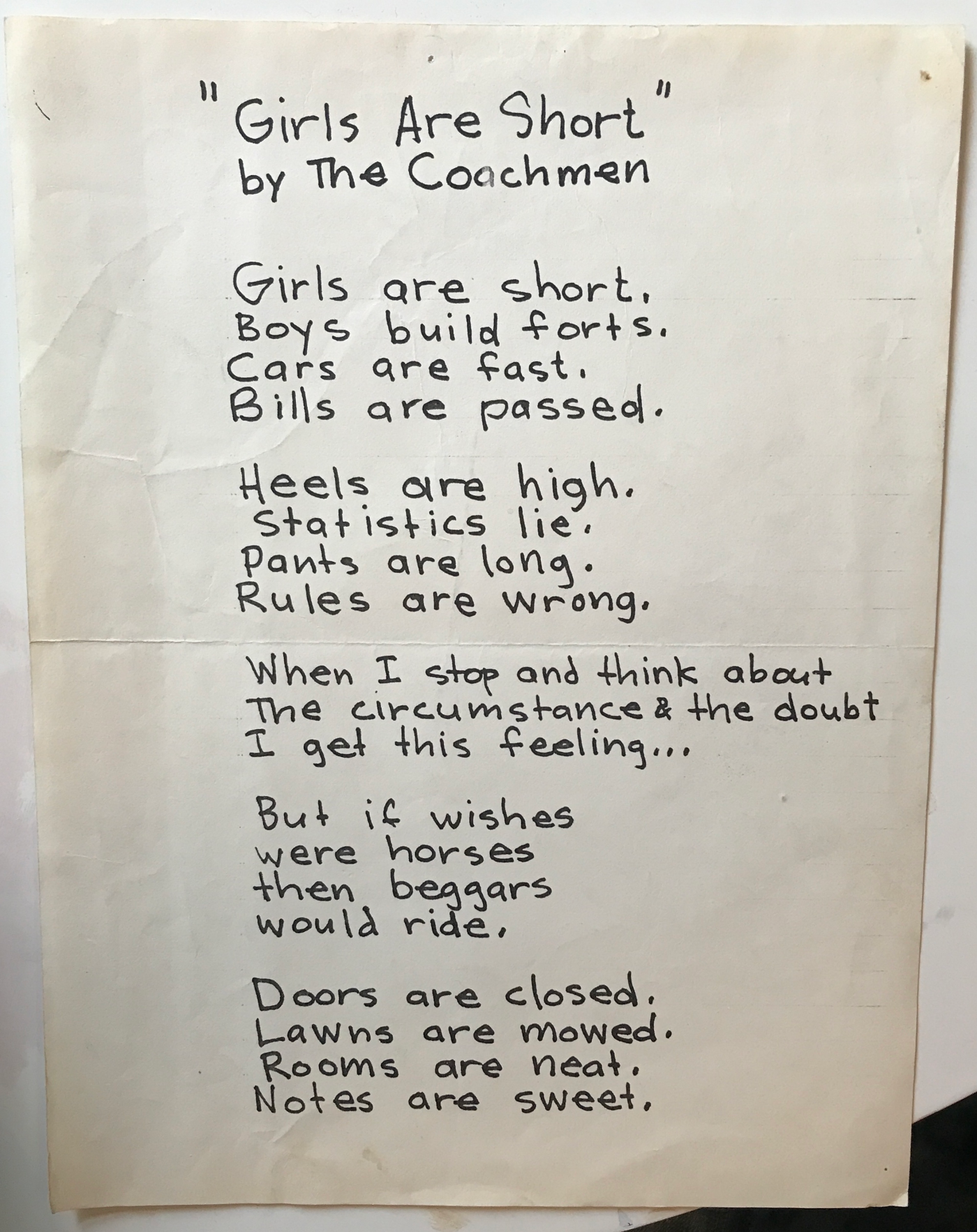

"[With The Coachmen], we were writing our own stuff," King told Cooke . "I wouldn't call it punk rock, but we liked Television. We liked the Ramones, the Velvet Underground, early Talking Heads when there were a trio...we liked Elvis Costello and Thurston was really into punk rock."

The Coachmen broke up in 1980 and Moore went on to put together the basis of what would be Sonic Youth. All the while, King hustled to piece together a career as a cartoonist.

"I always remember that kind of frustration on his face coming back after a day of pounding the pavement [looking for work in the late 1970s/early '80s] when we lived together on South Street," Moore said. "And I remember thinking, god, that's a tough gig, you know, just trying to get your foot in the door."

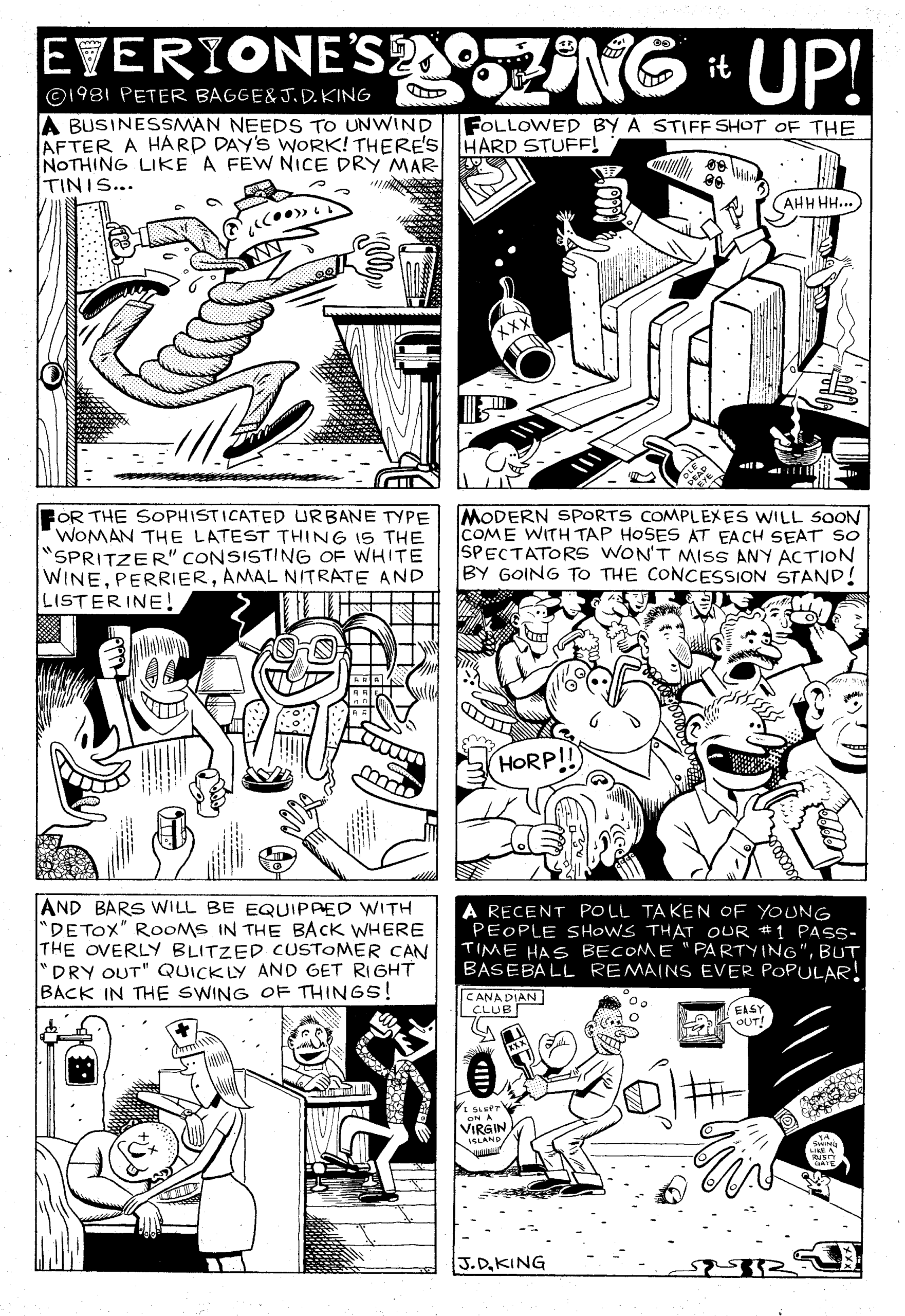

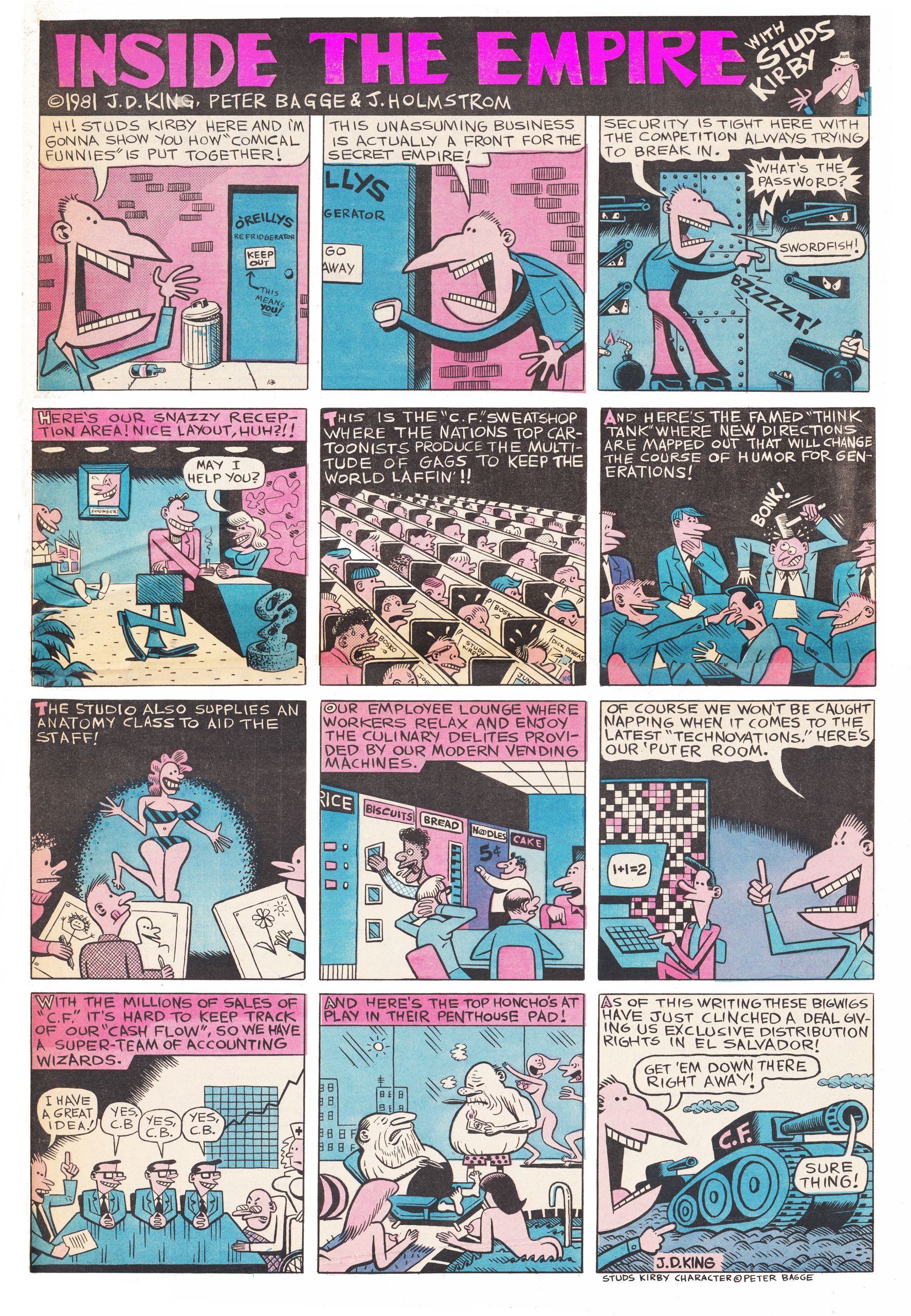

In Cooke's The Book of Weirdo, King said: "In 1980, after six years of trying to get published in underground comix, I got a break when I joined the Comical Funnies crew that's emerged from the wreckage of PUNK magazine: John Holmstrom, Peter and Doug Bagge, Bruce Carlton, and Ken Weiner. I hopped on board the second issue with some reprints of stuff I'd done for the Village Voice, circa. 1978."

In that 2019 interview, King told Cooke that getting published in Comical Funnies was the high point of his career: "Thurston was saying, oh, Holmstrom has got a new book out. And there were posters up on the utility pole, right on our block. Comical Funnies...And so I sent them some samples and I got a call from Bagge and he goes, 'oh, would you like to be in the next issue?' Something like that. And that was the happiest I'd ever been about any acceptance for work...That was it. Yeah. Getting into Comical Funnies...nothing ever since, not doing commercials, advertising stuff, magazines, book covers, whatever. Nothing else was like that, because that's what I really wanted to do. It was a great little magazine."

One of King's strips that ran in Comical Funnies, "Skank, Arms & Bud," was chosen by Robert Crumb to run in the third issue of Weirdo.

"I was ecstatic!" King said in The Book of Weirdo. "I mean–Crumb! In high school I discovered Head, then ZAP, then The East Village Other, and continued buying Crumb comix faithfully over the years."

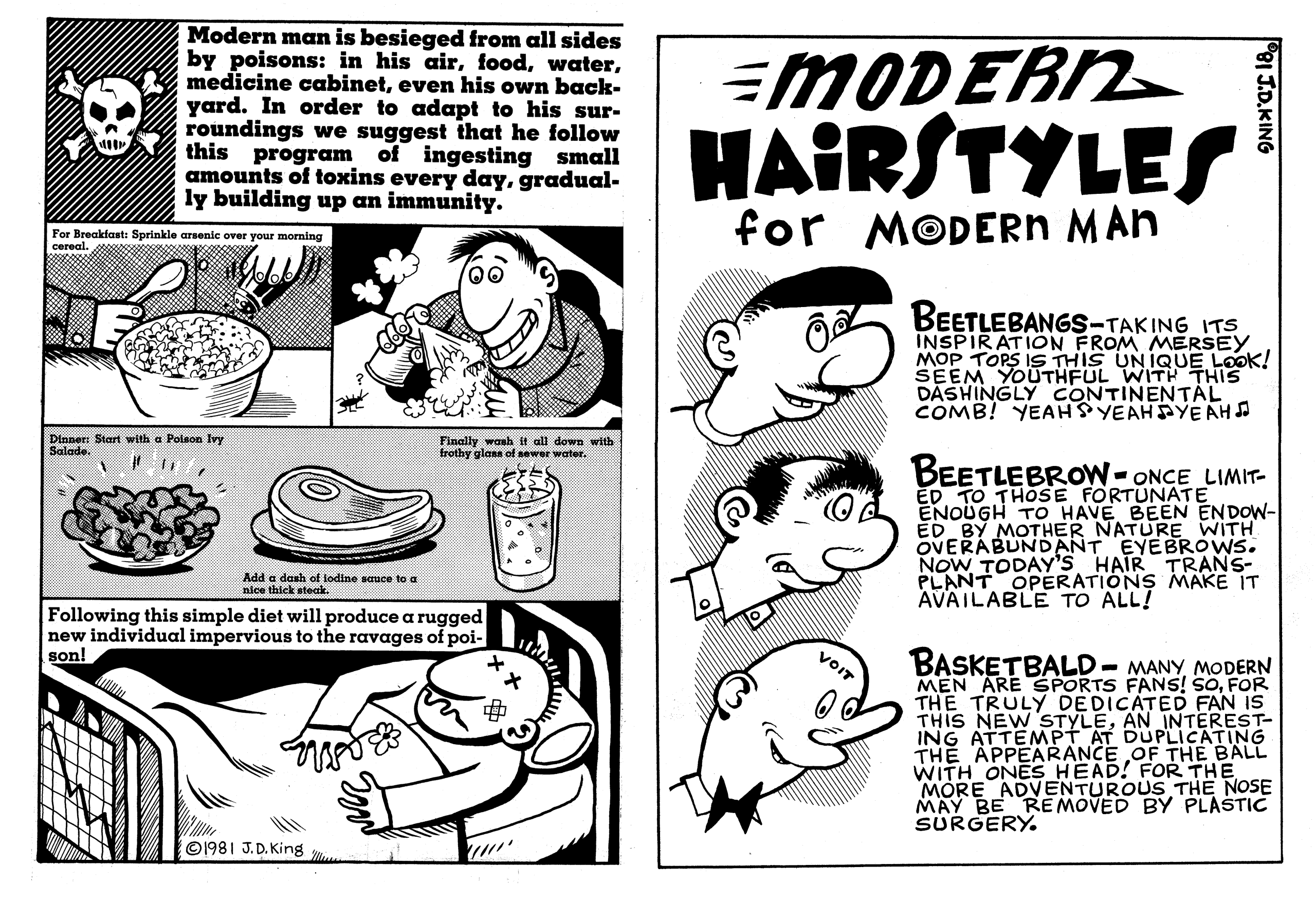

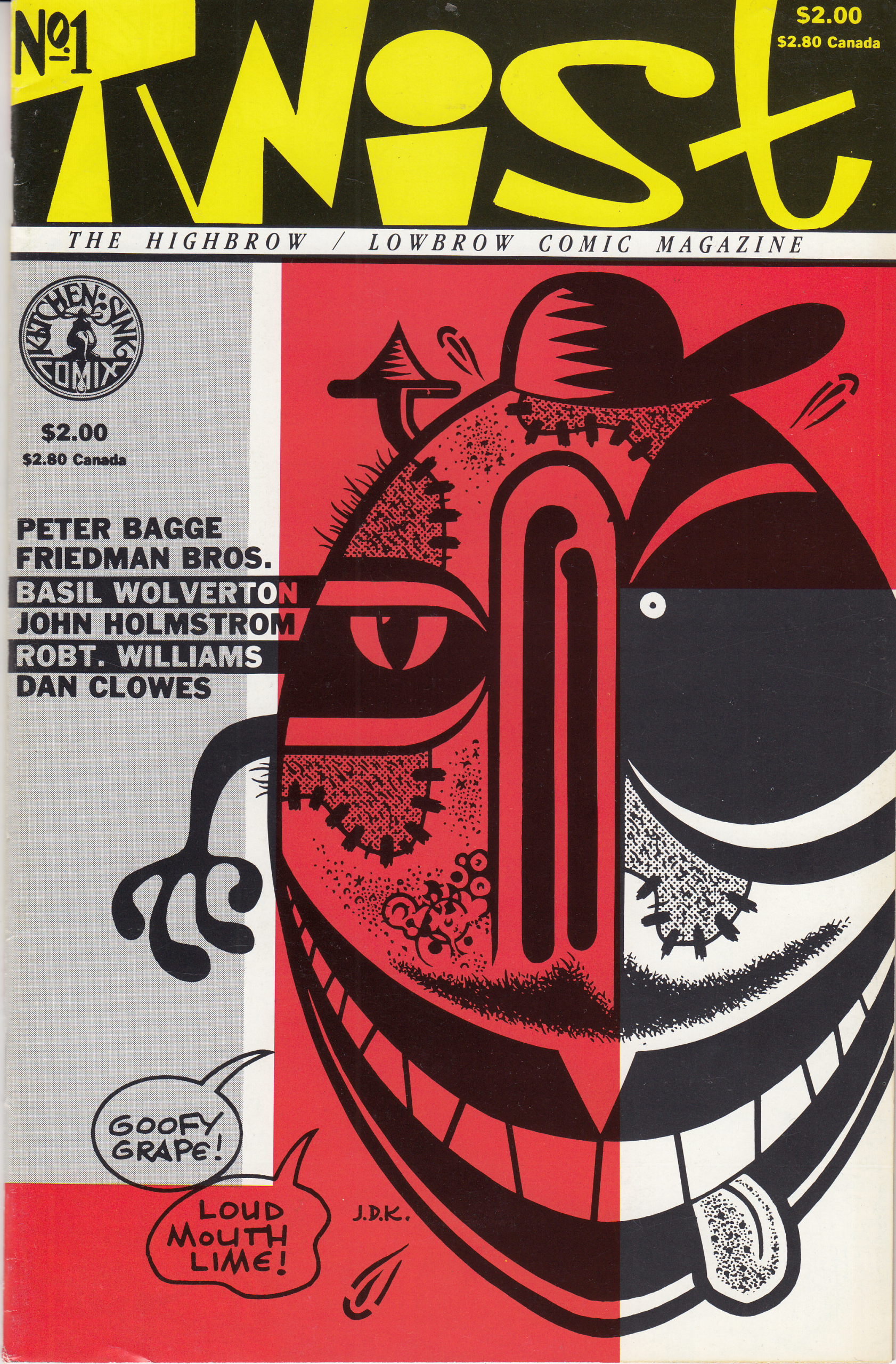

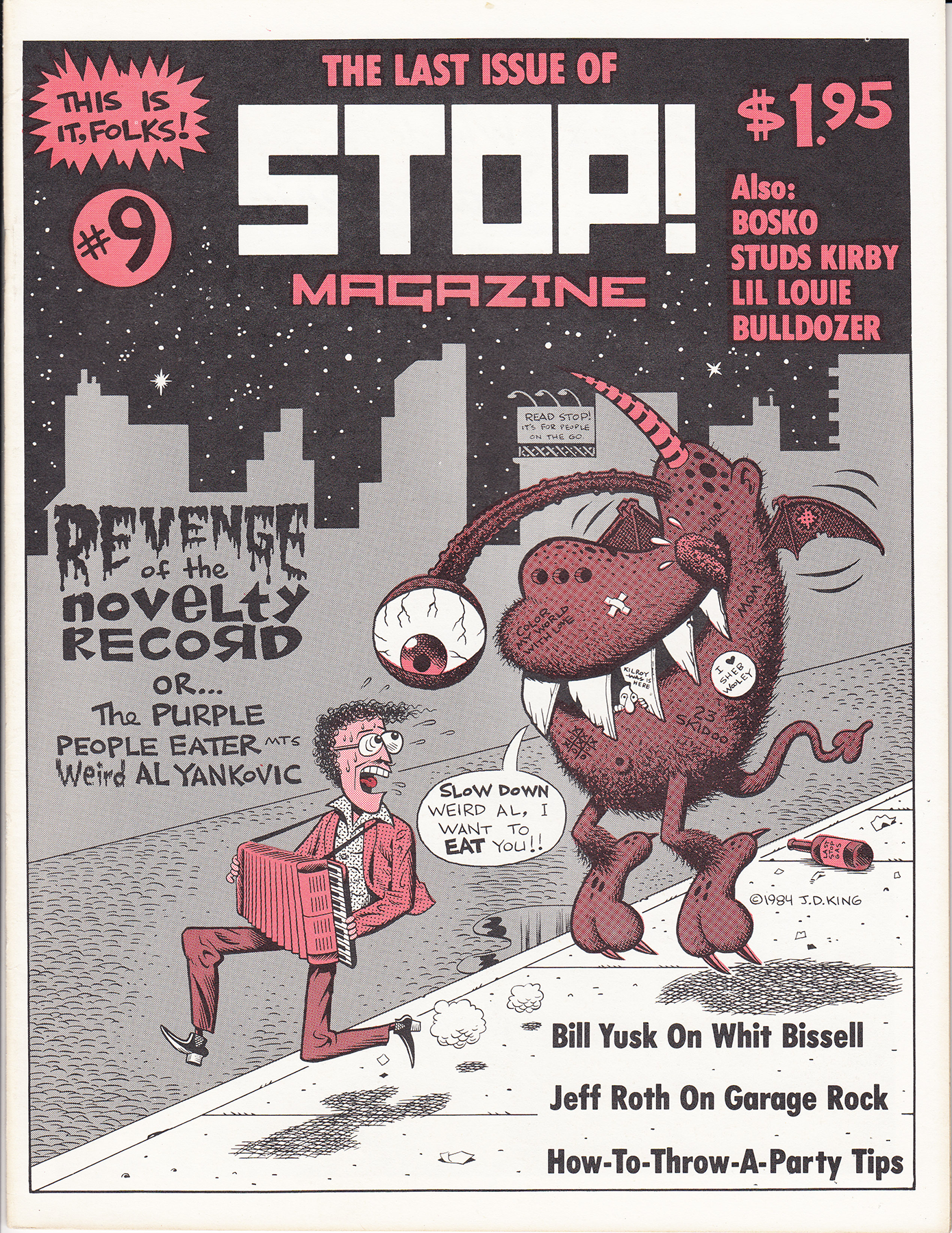

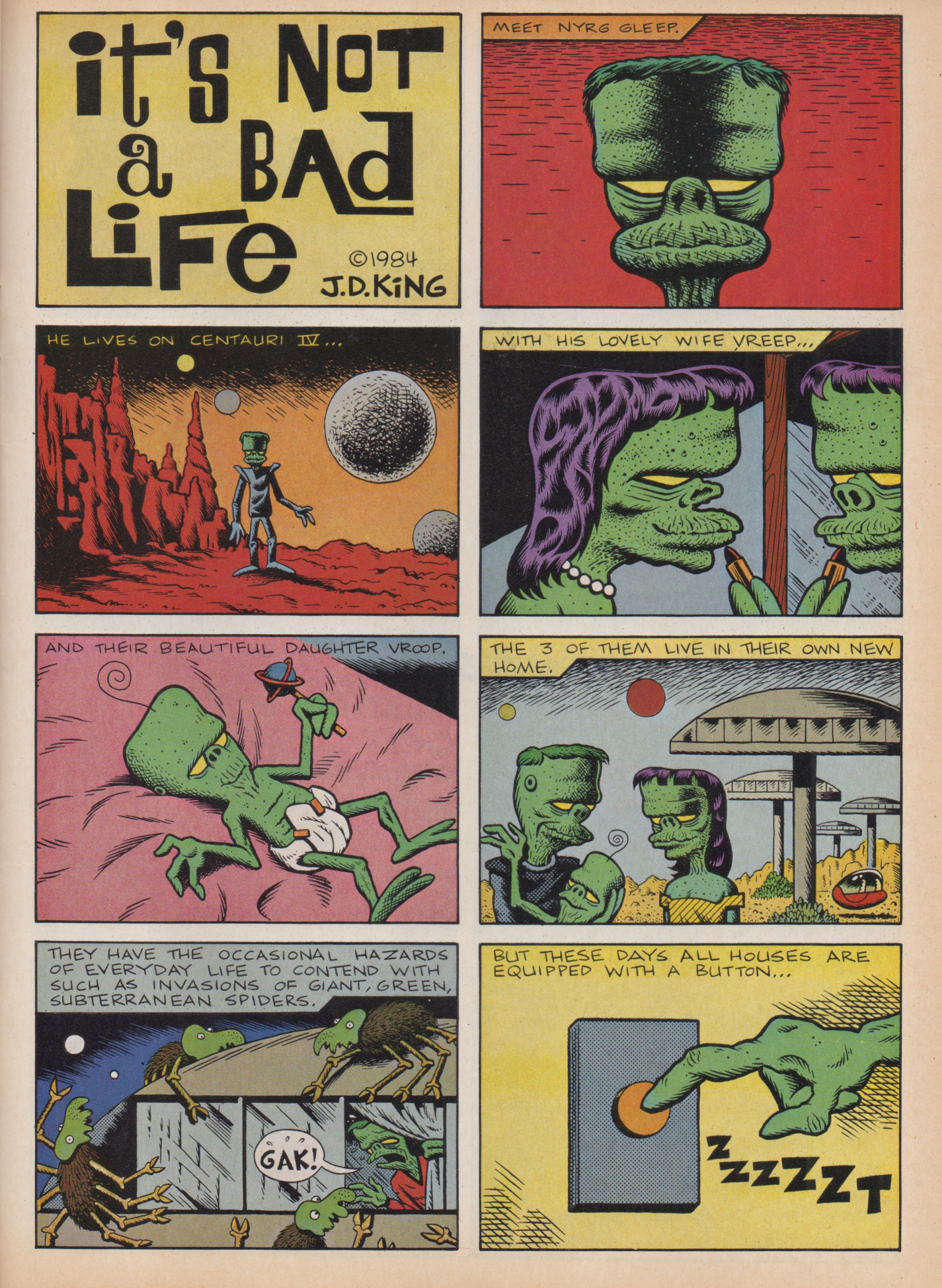

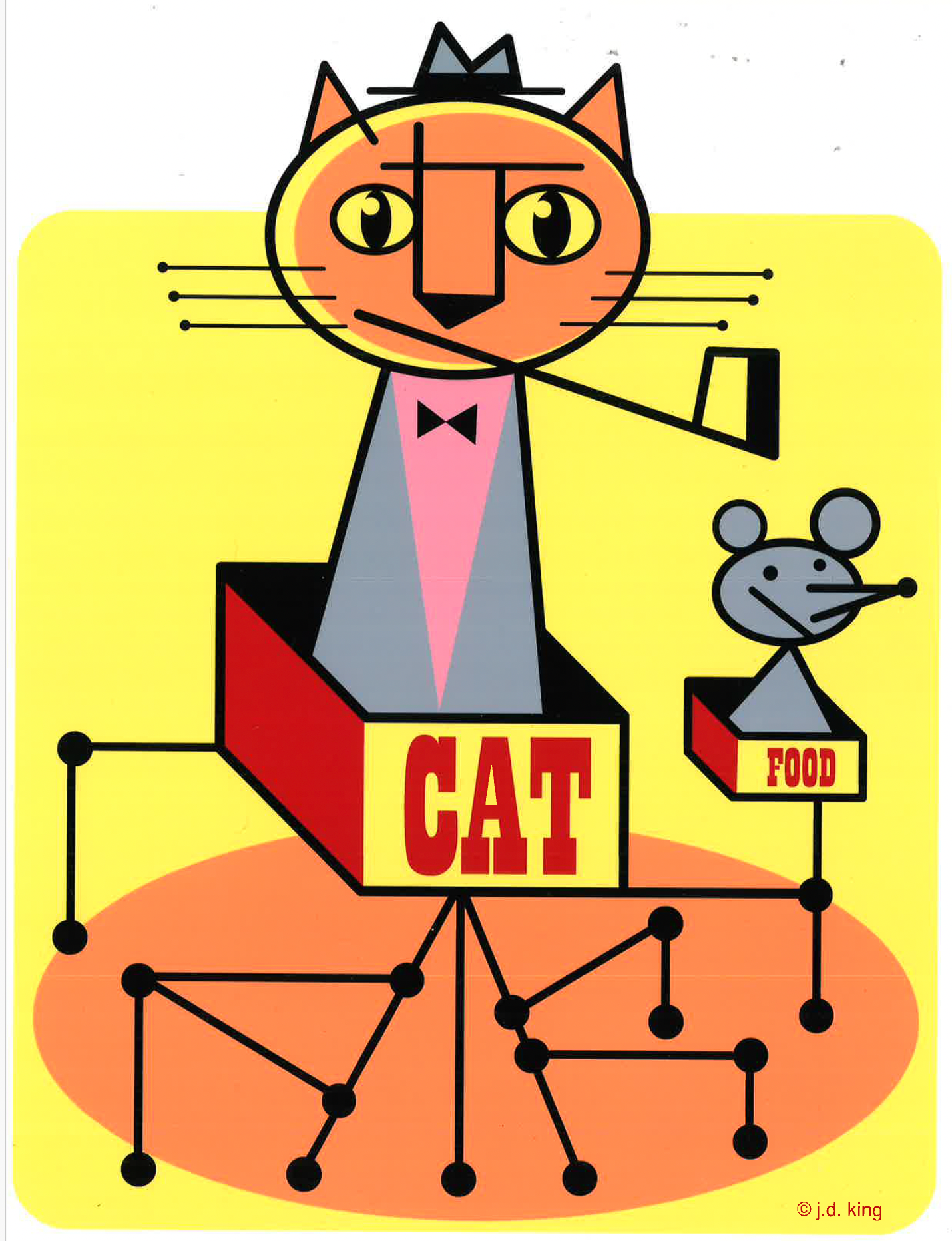

Comical Funnies ended after three issues and King and Holmstrom then put together STOP!, a comics/music zine which ran for nine issues in the early 1980s. And King continued to contribute work for Weirdo under the editorship of Crumb and then later, Bagge. In those early pieces, his humorous comics owed much more to the work of Ed "Big Daddy" Roth than what was to come later, which was much more influenced by, say, Gene Deitch or Jim Flora. During the later part of the '80s, he edited three issues of Twist and by that time his geometric, hipster/jazz drawing style had emerged fully formed.

"There was almost like this huge epiphany that he had, like Picasso finding Cubism as this great place for expressing...everything," Moore said. "And it was great the way that J.D. kind of took the piss out of Cubism...he was an art school kid who knew enough about art history that he could kind of play with it and use it in a kind of farcical way in the context of comic art. He was kind of just messing with these significant and important motifs of 20th century art in comics art. Almost like bringing it down into the gutter where comics sat."

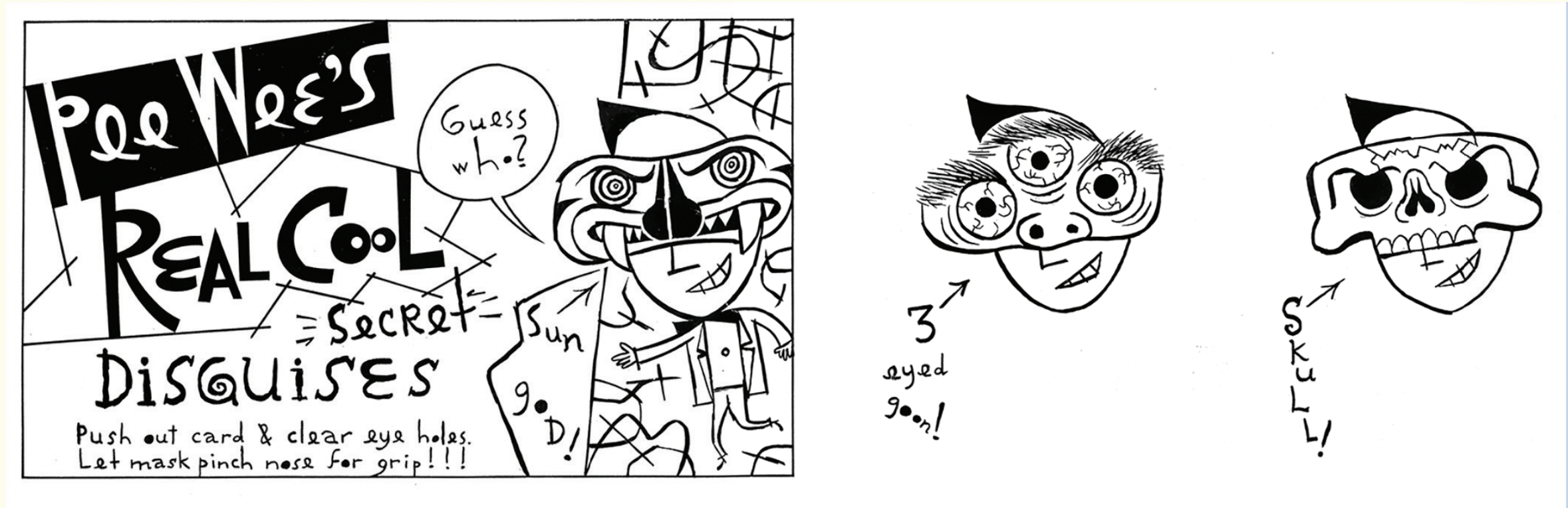

During those years his work appeared in many alternative publications, zines and comics anthologies–The New York Press, Kicks, Blab!, Drawn & Quarterly, The Duplex Planet–among others. In the late 1980s, King was among a number of all-star alternative cartoonists–Charles Burns, Kaz, Mark Newgarden, Gary Panter and others–who worked on an extremely ambitious project the Topps Company created for the popular Pee-wee's Playhouse Saturday morning television show; he contributed designs for the "Pee-wee's Playhouse Fun-Pak" series of trading cards, stickers and other items.

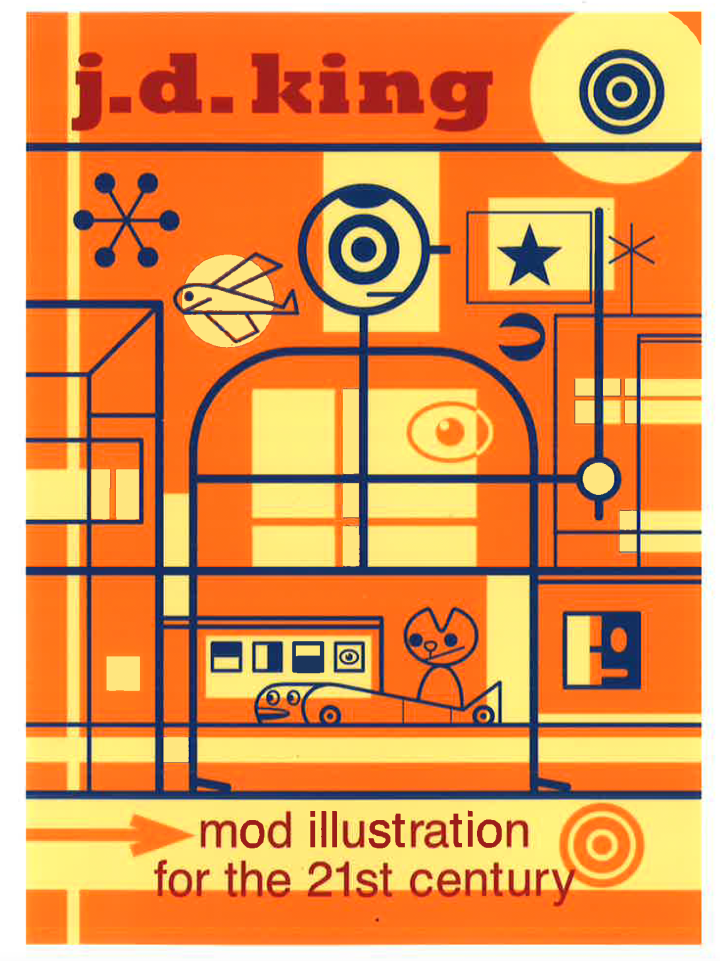

Like some other cartoonists at the time, he also began getting assignments for much higher paying commercial clients. And he had great success with his commercial work, creating ads for clients like Absolut Vodka, Condé Nast, Atlantic Records and others. His interest in creating comics seemed to go by the wayside.

"So I was, finally, an underground cartoonist," he said in The Book of Weirdo. "But, outside of Crumb and Denis Kitchen, many of those in charge were liars, sleazebags and crooks. At $50 a page (at best), it got to be tedious. An illustration career beckoned on the horizon with promises of real money, fewer headaches–and no hand lettering! I segued into a new life."

And things went well, until the work dried up and, as King often complained to others, assignments began going to artists who were working in a similar style to his own.

"I think he was frustrated by the whole industry of [commercial art]–I mean, who wouldn't be," said Moore. "He was frustrated by seeing certain younger artists who were, as they say, 'biting his style' a little bit, and making it a little more accessible, possibly? Which is what goes on. So, it's like being in an experimental rock band and then some, not so experimental rock band takes what you're doing and put it into a a safer place. I think J.D. sort of saw that happening with certain younger artists who were placing things in magazine. It would be like, 'Is that J.D.'s art?' 'No, no, it's too safe for him.'"

Also, by several accounts from those who knew him, King could be a fairly difficult person to work with. As one said, "I'm guessing that his career fizzled because he was either impossible to deal with, or he couldn't stand to work with anyone."

"Some things [that] I have learned about myself over the years are, number one, I'm an introvert," he told Cooke. "And number two, I am a 'highly sensitive person.' Somebody told me to get this book about highly sensitive people. And it has this whole checklist of 21 symptoms of being a highly sensitive person. It's like ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, right down the line. The only one I couldn't check 'yes' to, because I didn't have an answer for it, was, 'did your parents and teachers discuss this about you?' And I said, I don't know. Probably not. They didn't have me in a meeting. I mean, it also has to do with attention deficit..."

The other thing that happened was the internet, which changed the rules of the game completely as print publications migrated online. The professional lifespan of even the most successful commercial illustrator can be extremely short. And extremely frustrating. This was true even when there was such a thing as printed magazines and newspapers; for most artists working in that field, things began to go south with the rise of the internet in the later part of the 1990s. King said the World Trade bombing on September 11th, 2001 also played a significant role in the changing tide–"After 9-11, at least for humorous illustrators...forget it"–and publications were using more stock illustrations.

"In August, 2001, my agent sent everybody a form letter and said, 'Things are not good...we think it's this...we think it's that...and maybe it's this, but there was this shift in 2001 where just all of a sudden stock illustration was having an effect," he told Cooke in 2019.

"He saved that letter for many years," said his second wife, Sally Eckhoff. "That letter, I think, was the end for him. I think he could have done a lot more, but [moving to Upstate New York and] and not being around New Yorkers, and the whirl of life, even if you're not talking to people, I think he really needed that buzz. And he gradually began to shrink. I think it's just the native fear that a lot of people have, about being out there in the world, but he had nothing to distract him from it."

In 1994, he and Eckhoff, moved from New York City to Stuyvesant Falls in Upstate New York. He continued to do illustration work for some years, but also worked on a novel, recorded some music and painted.

"I think that by the time he ran into me, he was kind of looking for a place to hide–and I owned this house [in Upstate New York]," said Eckhoff. "He was looking for a place to hide, so he could withdraw."

"I bet he just got tired of dealing with people and having to answer to art directors' criticism," said Brettschneider, whom he was married to in the 1980s. "It gets exhausting..."

In 2015, King's father died and left a sum of money to the brothers.

"After my father died, we both inherited an okay, but not mind-bending, amount of money," said Peter King. "But for my brother, who had never seen money before, he thought he was rich. So I just think he just packed it in early. He said, 'Screw it, I do all this work and there's very little reward.' So he just kind of bagged it, around eight years ago."

"Sometimes I wonder about the forks in the road," King told Cooke in 2019. "What if I'd gone this way instead? Would that have taken me somewhere else? What if I'd never moved to New York? What if I stayed in Providence? And I think, well, what would I have done?...You get older and nobody wants to hire you. And there are things about New York I regret, but what would I have done otherwise? What if I married the right woman? Had gotten a house way back when and it was all paid for by now...what if I stayed in New York? How could I survive in New York today?"

"I think the chaos of urban life was kind of enough for J.D.–he kind of had his fill of it," said Moore. "It's a commendable decision to make, to get away from the chaos of daily life. I don't think he needed recognition, at least the social part of it. He was a very social person, but he did't feed off of it. He really found a lot of joy in the physical world of 'things.' You know, amplifiers, guitars, records, a cool record player, a cool bicycle, a cat. For him, that was enough of the vibratory materials that he needed in his world. He didn't need to be at every gig at CBGBs every night or something like that."

***

I first met King in the early 1990s at a party thrown for Harvey Kurtzman. I had been chatting with a friendly, nattily-dressed, very tall man in a sharkskin blazer and Poindexter glasses. When he introduced himself, he said, "I'm J.D. King." I looked at him and replied, "Of course you are." I was very familiar with his work and his be-bop presence perfectly fit his art's vibe. At the time I had recently acquired an early, bootleg, version of Adobe PhotoShop and had been playing around with the program's "shape" tool, a primitive feature that allowed the user to create simple, well...shapes–lines, circle, squares, etc. Somewhat as a joke, I suggested to King that he might consider using it for his illustrations, which at the time contained a lot of...shapes.

"It will cut down your time with the French Curve and ruler," I said.

Big mistake.

King glared at me and said, "I hand-draw everything and always will. I will NEVER use a computer for ANYTHING."

I shrugged and said, "Sorry! Just a thought..."

"The one thing that guy didn't want, was to be instructed about...anything," Eckhoff said when I told her that story.

Some time later, I saw that he was indeed using a computer for his drawings. All of them. It made sense and he was adapting to the times; while his original art for earlier commercial pieces could be vibrant jumbles of abstract compositions–with a lot of White Out and Zip-a-tone–the industry's shift toward digital media often called for a simpler approach. And King found a way to make it work. Some examples of his later digital commercial work can be found on his website. On the site, he notes that he retired from illustration in 2022 and was concentrating on writing fiction.

"He had a bad back and I think it was easier for him to draw with the computer," said Brettschneider.

And the computer served him well.

"His aesthetic was Adobe Illustrator before it even existed," said Mark Newgarden.

***

King transformed in other ways too.

"J.D. had been a socialist when I met him–or a self-proclaimed socialist," said his Brettschneider.

That would change.

Both of King's ex-wives–Brettschneider and Eckhoff–said that his shift toward right wing politics were troubling for them. Others who knew him said the same.

"He made it all seem like it was moral question for him," said Eckhoff. "He didn't like what was going on in society, he bitched all the time about...well, hip conservatives are very weird people."

"Over the years, J.D. became very conservative, which was very upsetting," Brettschneider said. "But I don't think it was baffling, in terms of who he was. He was just this extreme personality. I mean, it could have gone any which way...especially when it was first happening, he could have gone in any way. He could have become even more socialist...as long as it was an extreme, he could have done it."

In fact, at least for a brief period of time, King did become a socialist again.

"He was a contrarian," said long-time friend Jeff Roth, who said that following his divorce from Eckhoff , King had returned to socialism. "Some of it was just to be a 'punk.'..if you're a right wing reactionist, one of your favorite bands can't be the Weavers. But he still had his Weavers records. He still had his Kingston Trio records...It was complicated...he actually became less extreme in his last few years."

"He jumped around a lot to these different philosophical things that he did," said Eckhoff. "He got into this religious thing right away, and the right wing conservative thing, which he didn't tell me about–and I was married to the guy. I woke up one morning next to a guy who was ranting about welfare queens..."

Like most people, King wasn't loved by everyone. Several people who knew him who were contacted to share memories about him chose not to, citing his politics, or his personality, as reasons. Many more agreed to participate (in the space below), even if they found some aspects of King's views or behavior problematic.

"He was a great guy to work with," said John Holmstrom. "We stayed close friends throughout the years, never had a serious disagreement, tolerated each other's weird political views and never agreed on most stuff... But none of that mattered because we were always friends first. I wish the rest of the world could understand that."

In a February, 2025 email to his former publisher Denis Kitchen, King wrote: "I don't argue with people. I used to but it's waste of time and energy–especially online. I'll discuss face to face, but if it turns argumentative, time to back away."

***

He is survived by his brother Peter. A memorial for him is planned to be held during the events surround the "50 Years of PUNK" magazine exhibit held at New York's Ki Smith gallery. Details will be posted when they are set.

In the space below, some who knew or worked with him, share some memories about him.

***

Sally Eckhoff

painter/writer/ex-wife

The Village Voice was a great employer of artists in the old days, and J.D. King was sauntering down Broadway on this sunny afternoon, his eye on the skyline, sporting an early Bill Evans be-bop look, when we had our first conversation. Though he moved to freezing upstate NY soon after, in 1994, the real J.D. was always a city-dweller, a skeptical, friendly flâneur.

I was on my way to Books of Wonder to pick up a copy of The Sailor Dog.

“Remember when Scuppers sails to Morocco and then goes to buy clothes?” J.D. asked. We had both been struck by Garth Williams’ illo of the hero dog trying on a pair of wingtips. Dapper, serious, formal, totally impractical: the dog and J.D. had a lot in common.

But J.D. didn’t like dogs all that much. His thing was cats. And solitude.

Country life never really touched J.D., though he rescued turtles and frogs with great skill. He’d wear his flat-front chinos and natty suede desert boots to the dump. When he went running, you could drop him anywhere and he’d glide along the hilly rural roads of Columbia County until he got bored, like an enormous expat gazelle. J.D. rarely broke a sweat. I think he considered it undignified.

A new superpower was born: J.D.'s instinctual connection with the homelier animals of the neighborhood. He preferred moths to butterflies and fell completely in love with the local donkeys—"so exciting, all brown and gray." Over time, he began to resemble the turtles he loved so much. J.D. retreated into his shell. He vacillated between his natural sweetness and a furious resentment of what he thought the world was coming to. We had been married in a field of sunflowers; finally, a dozen years later, he moved west with guitars and cats, and settled between the decaying old factory towns of Herkimer and Utica. Magnificent in summertime, Oneida County is the icy buckle on the snow belt. Still, J.D. never left upstate New York.

The arrival of digital technology made J.D.’s already-distilled work even more concentrated. Isolation made it somehow larger and darker. But it retained its cubist/animal nature. And it never lost its innocence.

Peter Bagge

cartoonist

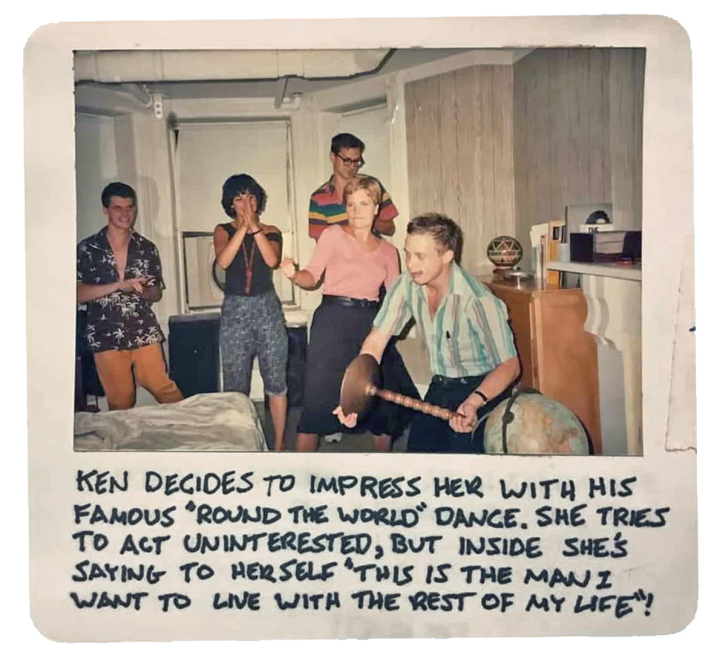

I met J.D. King back in 1980, when he submitted his work to Comical Funnies, a tabloid that me, John Holmstrom, Ken Weiner and Bruce Carleton had just put out. We all agreed that his work was perfect for our publication, and he immediately became a central part of our little clique. J.D. had an artistic sensibility that I found flawless. It encapsulated all the pre-hippie 1950s - '60s cartooning and cultural references that we both loved so much. J.D. also was always steeped in a nostalgia that could be freakishly specific. For example, he once told me that he longed to be a Jewish communist from the 1950s. Not that he himself believed in communism, mind you. He just wanted to BE one. A Jewish one. In the 1950s. In fact, it was during this "Jewish Commie" period that he called my wife asking for help in making borscht. All he had so far was a giant turnip sitting in a pot, and he had no idea where to go from there (I remember my wife replying "a turnip?").

J.D. was also one of the funniest people I knew, even if his sense of humor was very much on the snarky side. For example, his "imitation" of a young Elvis Costello consisted of him lowering his glasses, getting up in my face and going "Girls HATE me WHAAAAH!", which never failed to crack me up. And on the rare occasions some obscure zine would interview him, he delighted in lying about everything, just to see if the interviewer would buy it. When one zinester asked him how he spent his free time, J.D. replied "I spend it dreaming about ancient Alexandria. Ahh -- now there was an age!" He also once inexplicably decided that I was singer Jim Croce's biggest fan, even though I never once discussed Croce with him. I neither loved nor hated Croce's music. I never even thought about it! Yet I just recently came across some old fanzine interview with J.D. from that time, where, apropos of nothing, he kept telling the confused 'zine editor how much I loved that man's music. When I later asked J.D. what the hell that was all about, he just dug in his heels. "Admit it! You LOVE Croce!" Oh, okay. I'm sure he simply heard Bad, Bad Leroy Brown playing on the radio one day, imagined me being totally into it, and then pissed himself laughing.

Over time this snarkiness became a bit much. Like too many people I knew back then, J.D. got into taking part in "pranks," though many (all?) of these pranks tended to be thoughtless, or even downright cruel. He was stuck in a state of arrested adolescence, and–at least from what I could see–showed no signs of getting unstuck. So we grew apart. But I always loved J.D.'s art, even more than I love Jim Croce's music. I even love his latter "jazzy" stuff! It all still looks perfect to me.

John Holmstrom

cartoonist/co-editor, STOP!

I knew of J.D. King's artwork after a comic strip he did called "Monster Beach Party" was published in the Village Voice. It seemed suspiciously based on "Mutant Monster Beach Party," which PUNK magazine had published earlier. I liked the guy's style, but by then PUNK was going under.

After I started publishing Comical Funnies with Peter Bagge in the early 1980s, J.D. King showed up with his stuff. His style fit in perfectly with the rest of the wacko stuff Peter and I were publishing, so we published his "Haircuts" page in CF #2, and ran several pages of his comics in the third issue. By then Peter and I were having disagreements about the direction of the publication; I wanted more magazine-style articles while Bagge wanted it to be strictly a comics publication. So we parted ways.

Peter and Ken Weiner published their own comic book [Wacky World, 1982], which led to Peter editing Weirdo for R. Crumb, while J.D. and I published STOP! magazine, a zine with articles and comic strips and advertisements. We published nine issues, but by 1984 decided to "STOP!" publishing the magazine. We were both happy that we came away with a few hundred bucks apiece! Not a lot of money, but it was nice to break even at the end of the day.

A few years later, J.D. was changing his style: The 1960s/70s underground comics style took too long and wasn't attracting many commercial art jobs. He also started his own comic book: TWIST. TWIST reflects the new direction his art was taking: He was taking influences from UPA animators, John Held Jr., Gene Deitch and others. Somehow, his new style caught on and he enjoyed a very successful commercial art career for many years after.

I am putting together a memorial (above) for J.D, King that will take place on November 29, 2025 at the Ki Smith Gallery, where we will exhibit his artwork, animations, and stuff by his close friends (like me!).

Miriam Linna

writer/musician/editor via KICKS magazine

Smart, savvy, sophisticated, that was J.D. King , and he somehow managed to sandwich all that 1969 GQ classiness with an acerbic wit and unwavering teenage groan. He was a clean machine and his meticulousness translated across his love and creation of art, music, writing, and living. I couldn’t name another human on this planet who was kinder and more sincere than J.D.. The world’s a shoddier place without his bettering of it. I will dearly miss his regular installations of storytelling and his glorious stylized works of fine, fine art. A king in Kicksville for all time.

JJ Sedelmaier

animator

It was 1989 and had been working as the Executive Producer/Associate Director at R.O. Blechman's The Ink Tank animation studio for 5 years and was finishing the post-production on a project for Saatchi & Saatchi. After working on a project and spending a few days together in a post facility, you get to know the folks you're working with pretty well. The copywriter was Jane King and she was dead set on connecting her husband with me. He was a cartoonist and she was convinced that we'd be fast pals. Her hubby was J.D. King, and she was totally right! We became good friends both personally and professionally.

I didn't know anyone in my travels that had a graphic vocabulary like J.D. Whimsical geometry paired with humorous and bouncy characters and environs. It was both sophisticated and wonderfully inviting. And J.D. himself was an artful creation. Tall, with short hair, horned-rimmed glasses, and a fashion sense out of 1959. I couldn't wait to find the right animation project to plug J.D.'s art into.

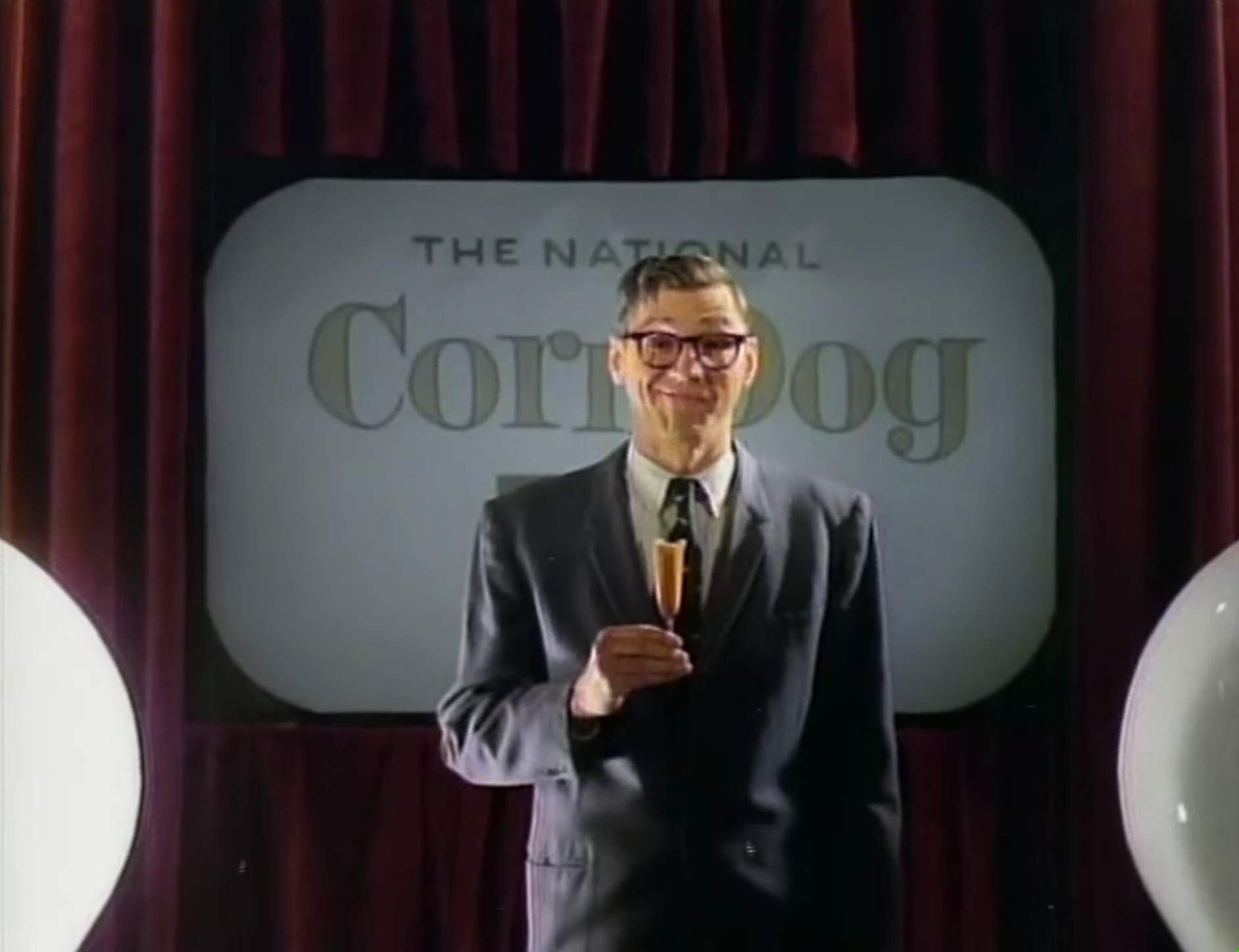

Soon thereafter I found myself working on a TV commercial for "Ball Park Franks." The spot was a throwback to all those retro television quiz games of the 1950-'60s. Cartoonist Ron Barrett had already been brought on as the designer of the cutaway art-cards, but we needed a spokesman to host the film. That's where J.d. came in. I convinced the ad agency - and Blechman - that J.D. would be perfect. And he was! He was the visual solution to the host issue and he had an authentic honesty and bashfulness that was a gift from the GODS. You can see for yourself here.

The next project I approached J.D. about was our first studio Holiday Card. After leaving The Ink Tank in 1990, my wife Patrice and I opened J.J. Sedelmaier Productions, Inc., and I couldn't think of a better way to grab people's attention than to have J.D. design an image for us to send out and announce our appearance in the industry. All I asked him to do was design a fun image that used a sequential foundation. Here is what he came up with:

Finally, the last time we collaborated was in 1992 on an animated TV ID for Nickelodeon's channel "Nick @ Nite." We produced a bunch of these short 10-15 second spots, and this was finally going to give us a chance to translate J.D.'s art into film. The soundtrack was done first and we developed a simple animated story around the tune and lyrics created by Tom Pomposello. J.D. not only designed the "look" of the spot but also did the storyboard. Here's the piece (animated by Mark Baldo).

J.D. and I stayed in touch through the years. His marriage to Jane ended and he later remarried. He was such a sweetheart of a guy...I was gobsmacked to hear that he'd passed away. I'll miss him terribly....

Denis Kitchen

cartoonist/publisher via Kitchen Sink Press

J.D. King’s drawing style---so simple and so elegant---stands out from all of his artistic contemporaries. He came from what I’d call the Gene Deitch School of Cartooning, with unembellished pen lines that seemed inspired by 1950s jazz album covers and beatnik aesthetics.

I no longer recall when or where J.D. and I met. It was probably a long-ago comics convention. I’d certainly been aware of his work in Weirdo and other alternative zines, but when we got to know each other, it was a quick and lasting friendship.

As Kitchen Sink Press’s publisher, I agreed to publish---and even contributed to---Twist, a short-lived post-underground anthology that JD pitched to me in the late 1980s. The black & white self-described “High Brow/Low Brow” publication contained comics and illustrations by the likes of Drew Friedman, Dan Clowes, Kaz, Richard Sala, Robert Williams, Patrick McDonnell, Peter Bagge, John Holmstrom, and others---even a non-cartoonist like Jenny Holzer---all testimony to J.D.’s persuasive arm-Twisting skills, since no one got rich from the page rates. He also included homages, reprinting excerpts of admired earlier generation talents Boris Artzybasheff, Basil Wolverton, Harvey Kurtzman, and David Levine. J.D. and I were definitely on the same aesthetic wave length.

But, after three issues, despite the impressive contributor line-ups, sales were discouraging enough that I had to cease publication. J.D. chose to personally draw and design all the Twist covers, and I strongly suspected that the poor market reception was the result of consumer resistance to his own cover art. They were bold and eye-catching, but probably too different looking and too eccentric compared to anything else on the racks. Comic shop retailers and collectors had largely conservative tastes back then. Did I say “then”?

I suppose I could have pulled my publishing muscle and insisted that the covers be drawn by more market-friendly creators, but that would have disrespected both J.D. and the editorial control I promised him, and I was a friend, not just a publisher. No regrets, other than I’ve sometimes wondered how Twist might have evolved under a publisher with deeper purse strings or market clout.

J.D. and I continued to stay in touch, mainly via email. He had stopped drawing altogether in recent years but he loved playing the guitar, and I hope he was strumming tunes right up to his unexpected demise.

Mark Newgarden

cartoonist

J.D. King was a fixture of the New York City comics scene in the early 1980s as well as the New York Press crowd a bit later, and we crossed paths many times over the years. Yet he always remained something of a mystery to me.

It should be noted that in the early 1980s, there existed several discrete factions of “alternative” cartoonists in NYC. Two of these groups revolved around the twin hubs of Raw & Bad News on the one hand, and Comical Funnies & Stop! Magazine on the other and we clashed on every possible level. As polarized as those factions could be, the boundary lines weren't strict enough to prohibit some cross-pollination, particularly at various social get-togethers. I remember attending (crashing?) several Stop! cartoonist events at various venues over the years including one at King's apartment, where his then-wife Jane was a charming & memorable hostess. And in turn, J.D. showed up at some of ours as well.

King himself was brooding and somewhat Frankenstein-like and he dressed like he had just stepped out of the tall boy's section of the 1966 Sears Roebuck catalogue. He sported heavy black eyeglass frames with the thickest of lenses affecting a Steve Allen / public intellectual look, yet drank beer from the can and had a wonderful talent for bringing any conversation to a screeching halt. What do you say to a man who tells you with the deadliest of deadpan expressions that the pinnacle of American animation was achieved by the Woody Woodpecker cartoons directed by Paul J. Smith in the 1970s? (He really liked the Beary Family too.)

I could see a reflection of that kind of humor in his work at the time, but his main artistic influences seemed to be the unlikely combination of Mort Walker and Big Daddy Roth (which I think he pulled off rather nicely). That later seemed to shift to the even unlikelier combo of Mort Walker and Paul Klee, a career move that I have often wondered about.

By the time the New York Press rolled around in 1988, J.D. seemed to be enjoying a hot moment with his artsy new cartooning style, and we both appeared regularly in that late and lamented alt-weekly. Rumor had it that J.D.'s new look had secured him a prestigious illustration agent, and he was setting his sites at nothing less than national ad campaigns and New Yorker covers. I don’t suspect that ever happened, but I do recall hiring him at Topps Chewing Gum in the bowels of Brooklyn (at the direction of Gary Panter) to contribute to a Pee-Wee’s Playhouse novelty series that we were concocting there. The Topps suits were suitably baffled by J. D.'s dry-martini minimalism, but he fit right in with the other off-kilter talents delivering the Pee-Wee agenda to America's youth.

I fell out of contact with J.D. as that era gave way to the next, although I would still see him "around", and then later in the digital "around" of social media, where he was now rumored to be bunkered deep in the woods of upstate NY, writing novels and awaiting Armageddon. (How true this might be, I haven't a clue). For me J.D. King remained a man of mystery to the end, and I think it's probably always good to have a few of those in the mix. So long, J.D. One less now.

Russ Smith

publisher, via The New York Press

I first met J.D. in the spring of 1988 at the Soho offices of New York Press, about a month before our first weekly issue was published. How he came to the attention of art director Michael Gentile and me is hazy—it might've been through Art Spiegelman or Mark Newgarden—but in the early years of the paper his block illustrations were on the back page each week, in the middle of the "extra-classified" section known as "Press Box." In September of '88, J.D. created the cover art for our first "Best of Manhattan" annual.

He was a regular visitor to the office, and, like many other artists, hung out in the production department with Michael and the late Don Gilbert. Michael told me: "On any given day of the week when I was art directing at New York Press, artists would drop by, carrying artwork in hand. Connecting faces with humans during the analogue days was important; these were original comic strips and illustrations. When the world's tallest cartoonist walked into the art department, heads would turn as excitement built. J.D. King would present a superb new pen and ink drawing, epitomizing the simple, sleek and modern. J.D. helped bring those newsprint pages to life. He played a crucial role in the paper's design and look. Our hours-long conversations about life, art and music will remain etched in my memory."

Before he moved upstate, J.D., in sports coat and tie, rarely missed our Christmas and "Best of Parties," and he'd nurse a beer, chatting amiably with guests. Memories from more than a generation ago are tricky, but I won't forget a particular act of kindness he showed me. I was a bit late to our offices (then at the Puck Building) one morning in June of 1990, and we arrived at the same time. He'd heard that my sister-in-law had succumbed to ovarian cancer two days earlier, and his words of sympathy weren't rote, but genuine and heartfelt. As I noted, J.D. traveled in different circles, but that was representative of the man I knew and liked very much. Nobody deserves a sugar-coating in his or her remembrance, and J.D. did have an ornery side, but fortunately I was rarely on the receiving end.

Just last May, in my weekly Splice Today feature "What Year Is It?," J.D. was the launching point. The story began: "My pal J.D. King is a titan. We met in a Parisian absinthe bar in the late-19th century (two glasses was his limit), took miles-long walks along the Seine, tried to out-do each other in recitations of obscure poetry and bruited about the daily headlines in Le Figaro. It was a swell time. At least that's what I imagine, and dissenters or 'haters' can take it up with Huey, Dewey and Louie, or, in extreme cases, Mary Worth. Brenda Starr's sitting this one out."

It was a goof, one which he appreciated and then made self-deprecating jokes on Twitter about it.

I found a 2011 story about J.D. in Utica's Observer-Dispatch, and Lisa Kapps writes: "[King] names artists like Paul Klee, Andy Warhol, Richard Paul Lohse, Jim Flora and Paul Rand. Musicians like Charlie Parker, Bill Evans and John Cage also have affected the way he creates an image." Not much to go on, but as I noted, J.D. valued privacy and didn't seek publicity.

In recent years, I got a kick out of jousting with him on Twitter (along with online friends @lambchops1, @sjgiardini and @davrola, among others) about music, politics and the media. Sometimes I'd include a gratuitous jab at Simon & Garfunkel or Pat Boone in an article, knowing that would get his goat. An early-riser, he'd make cracks right away (including the internet cliches he knew would bug me) and a small Twitter thread would follow. It was a very small corner of the social media world, but I sure enjoyed it and will miss it, and him, very much.

Michael Gentile

art director via The New York Press

Working at NYPress as the founding art director, I commissioned covers, artwork and photographs covering stories from the serious to the absurd. Artists regularly dropped by the Puck Building to deliver their original camera-ready, comic strips and illustrations in-person.

When a frequent and popular visitor, J.D. King, walked into the room, our entire staff would turn around to see "The world's tallest cartoonist." These were intoxicating times in the art department. J.D played an important vital role in NYPress' early publishing days. In addition to designing the first poster for the 'Best of Manhattan' issue, he was also a featured artist in the Absout Vodka series ads. His weekly comic strip called "J.D. King Feature" ran front and center on the newspaper's back page for many years.

The slender, outgoing bespectacled hepcat with a charismatic smile, instantly captivated me with an appreciation of his work. And he liked cats too. The artwork featured a fresh clean aesthetic; hand-drawn pen and ink panels with a simple modern look. These were eye-catching images, full of strong shapes, solid lines, dots and geometric patterns. To my delight, J.D. and I had hours-long conversations about the wild work of Jim Flora. Our diverting cultural discussions would stray, sometimes going on for hours. His supreme wit could on about the importance of improvisation. As post-punk idealists, we'd crack-up over running jokes about Dee Dee Ramone becoming hip-hop rapper "Dee Dee King."

The independent NYPress artists' engaging voices spoke directly to its diverse readership. It was a pleasure meeting and listening to Ben Katchor, Kim Deitch, Kaz, Mark Newgarden, Carol Lay, Mark Beyer, Tony Millionaire and many others who helped refine the newspaper's pages. Communication in the analog era relied heavily on connecting faces with ideas and real people. Even though the golden years of newsprint are long gone and disappeared, the work of the incomparable J. D. King lives on in our collective hearts and minds.

Rick Trembles

cartoonist

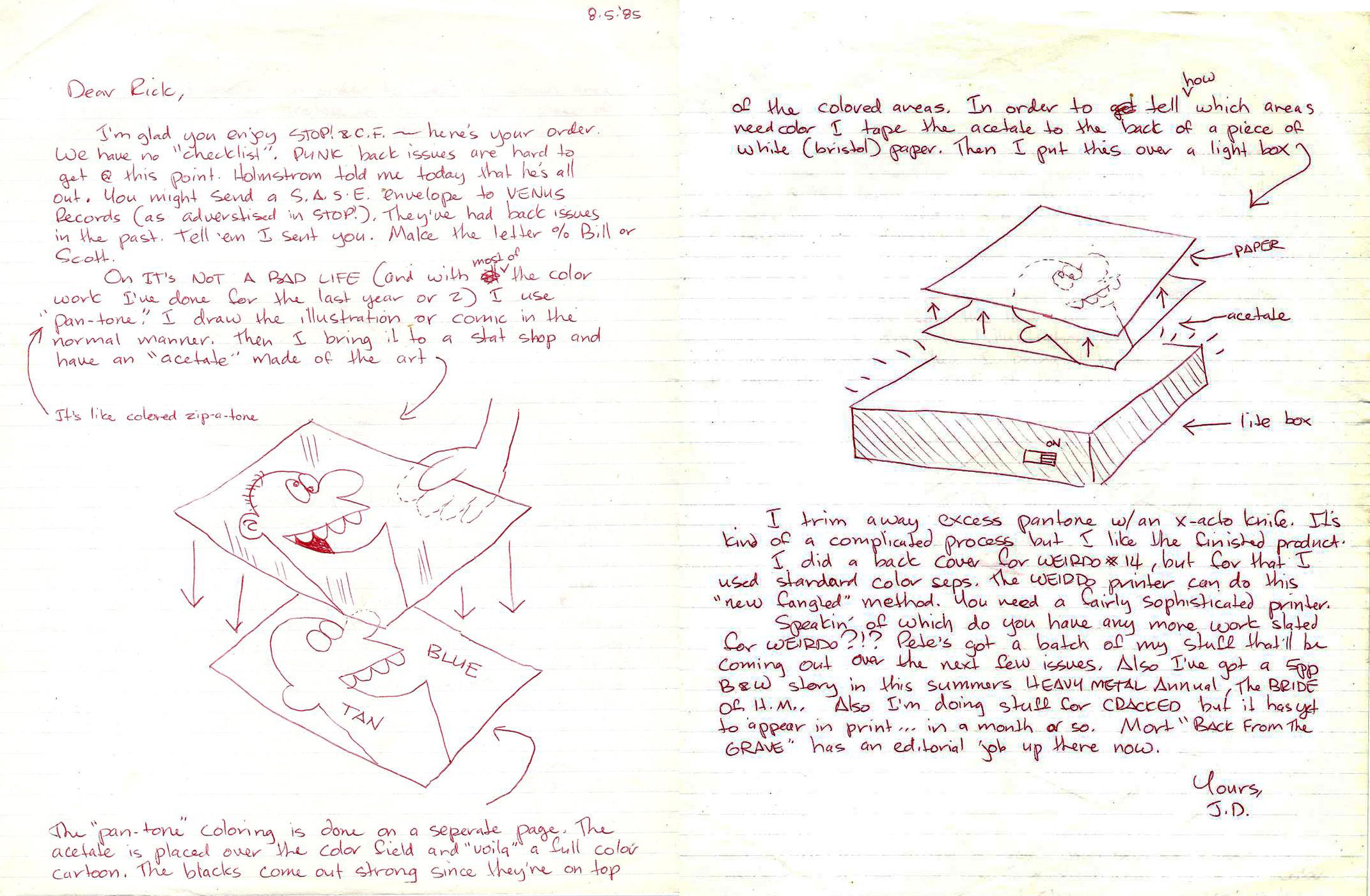

One of my favorite letters from a cartoonist ever! I loved J.D. King's stuff in Stop! magazine, Weirdo, and Comical Funnies, but the explosive colors in a comic he did for Heavy Metal magazine in the mid-eighties called "It's Not A Bad Life" had me writing to him to ask how the heck he did it & he generously took the time to write back and explain his color separation process. I miss writing & receiving snail-mail with cartoon drawings on them! His cartoon characters had a vintage ad mascot/logo design feel to them but with storylines contemporized to be punky kinda like Kaz. J.D. King came out of the post-underground/pre-alternative comics school of “laugh out loud” funnies with the likes of Peter Bagge and John Holmstrom, exactly the kinda stuff I wanted to do, so he was a big inspiration!

Courtesy Rick Trembles.

Jon B. Cooke

comics historian

When John [J.D.] was a student at RISD, because he was a comics fan, he struck up a friendship with my oldest brother. He was just a remarkably nice guy. He was remarkably talented. He had a real Jack Davis vibe to the work that he was doing at the time. I mean, a completely different style from what he developed later. And he was a clean-cut gent, you know, who liked the wacky shit. You know, he liked Harvey Kurtzman and EC Comics.

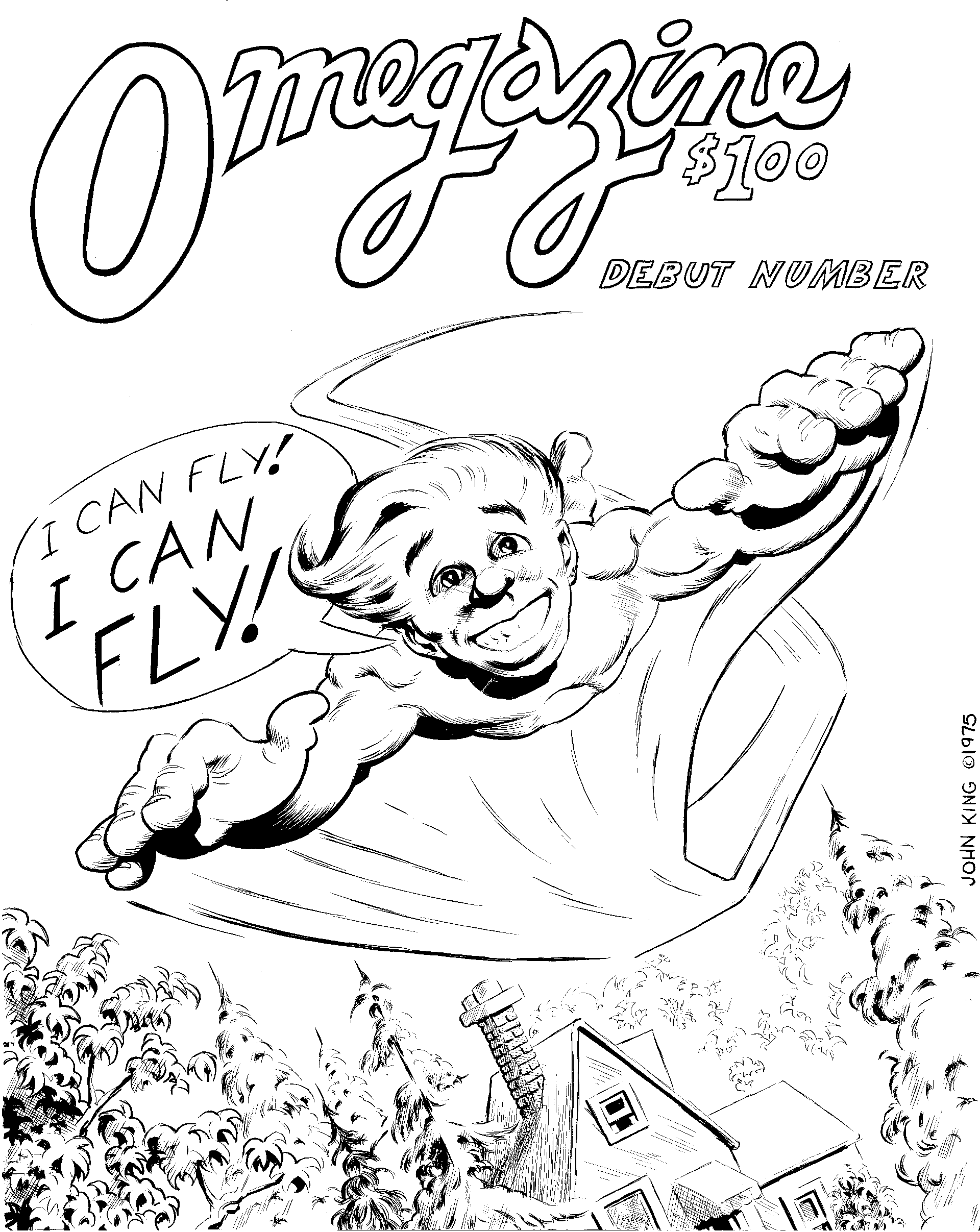

I wasn't really particularly tight with him–I was 13 and he was however many years older–but nonetheless, I do have a vivid memory of him being a very cool, nice guy, and a talented guy. So, I was doing a fanzine with my brothers, in 1975 and I asked John to do a cover. And he sent me one. He had renamed the magazine–I had a slightly different name. He made it better.

In the 1980s, I'd see the name "J.D. King" and I'd always scratch my head, wondering if it was the same dude. . I always knew him as "John King." And then I'd see the art and think, there's no way it's the same person. But we reconnected in the 1990s. I was doing my Comic Book Artists magazine and he must have picked up a copy. He reached out to me and we immediately hit it off again–as adults, as friends, as peers.

He was truly one of the nicest guys I've ever known. He was also just very modest, remarkably modest. Actually, self-deprecating to a point, you know? And he was being unfair to himself.

Dame Darcy

cartoonist

J.D. was a huge inspiration and a catalyst for positive change for me during a time that was so foundational that I have no idea what the decade of the '90s and New York City would have been if I hadn't met him. He didn't have to help me, he just wanted to. Because that's the kind of big-hearted guy he was.

J.D. introduced me to all the comics greats, including Art Speigelman, Ann Bernstein, Kaz, Tony Millionaire, and everyone who I'm still fortunate to call my friends. He was so genuine, and kind to set me up with illustration gigs at the New York Press and Village Voice. JD showed me the sights of downtown first. The West Village Jazz clubs he loved so much, China Town, and so many places where I went on to make memories for decades. But every time I go back I can't help but be reminded of J.D.

We went to CBGB's together and because of him, Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon became my friends and I was able to fulfill so many dreams. Opening up for Sonic Youth at what I perceived then to be ground zero of New York and becoming a professional illustrator.

All thanks to J.D.'s support and generosity. JD was and still is an icon to all who knew him. He left a legacy that will forever remain in the hearts of those who connected with his art and his soul.

Rest in peace my dear friend.

You are loved.

The post RIP J.D. King – 1951-2025 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment