A young woman bound to a post by the neck, her wrists and ankles restrained, breasts pinched with clothespins, writhes as best she can, moaning in despair out her feces-encrusted mouth. Excrement black as tar erupts beneath her open kimono, her bare rear concealed by a calligraphic exclamation in a caption elegantly composed to both cover and define the obscenity -- “DEFECATION.” The words of an omniscient narrator declare her “Pig woman [...] so shameful... so stinky!” defining the victimized woman as a permanent object, as if to admonish us not to pity her. The room is barren, dark, almost manicured, a mirror and the likeness of a single autumn leaf upon a sliding door hang in the negative distance. The possibility of serenity is shattered by the clamour of her shit, a shuddering BIIIIII (translated “splurrrrt”) erupting down the center of the panel. This moment is decorated with a theatrically patterned border, its corners adorned with further reminders of the corporeal abject -- PISS SHIT MAGGOTS FECES. This is an SM illustration, but it is also a thesis statement.

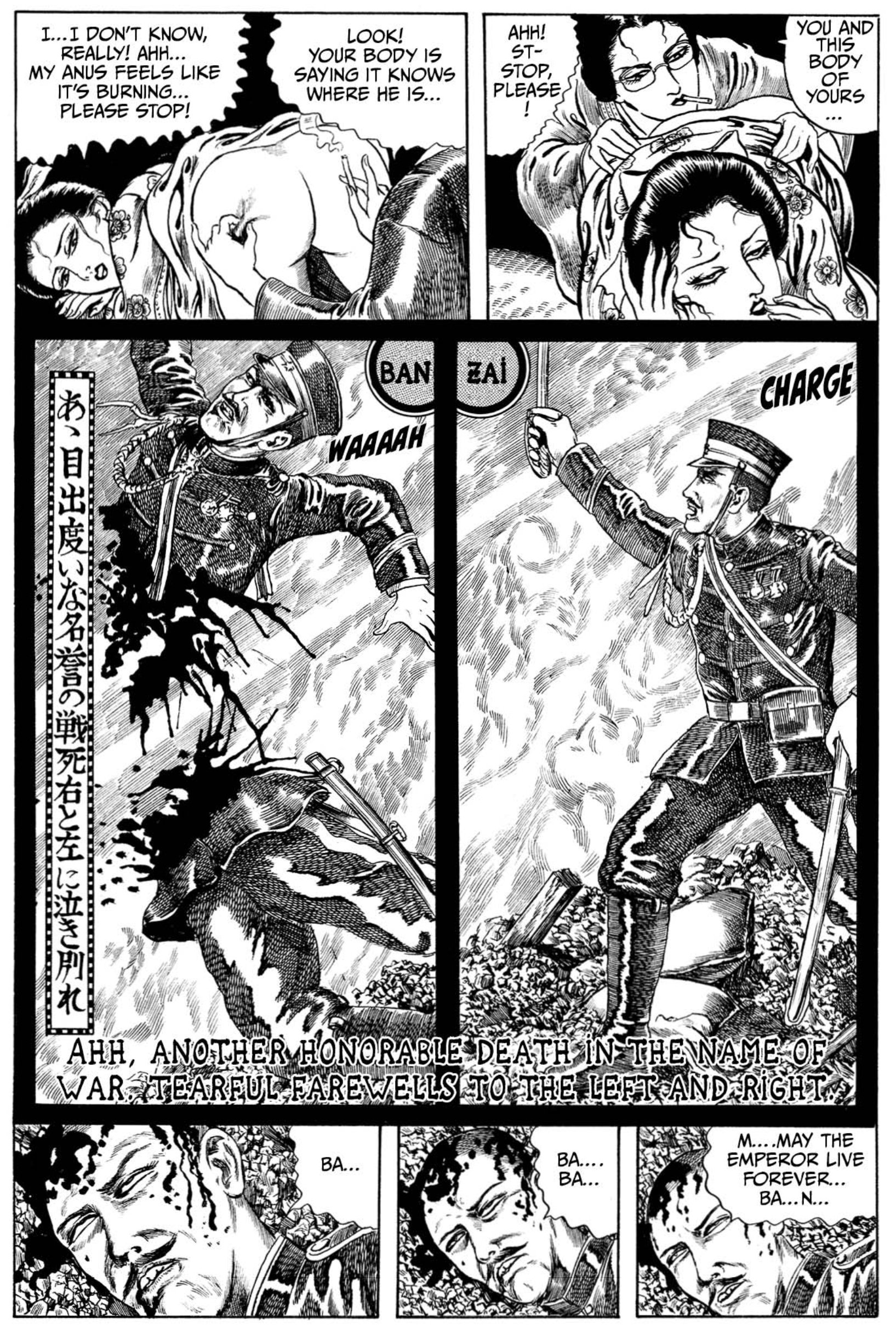

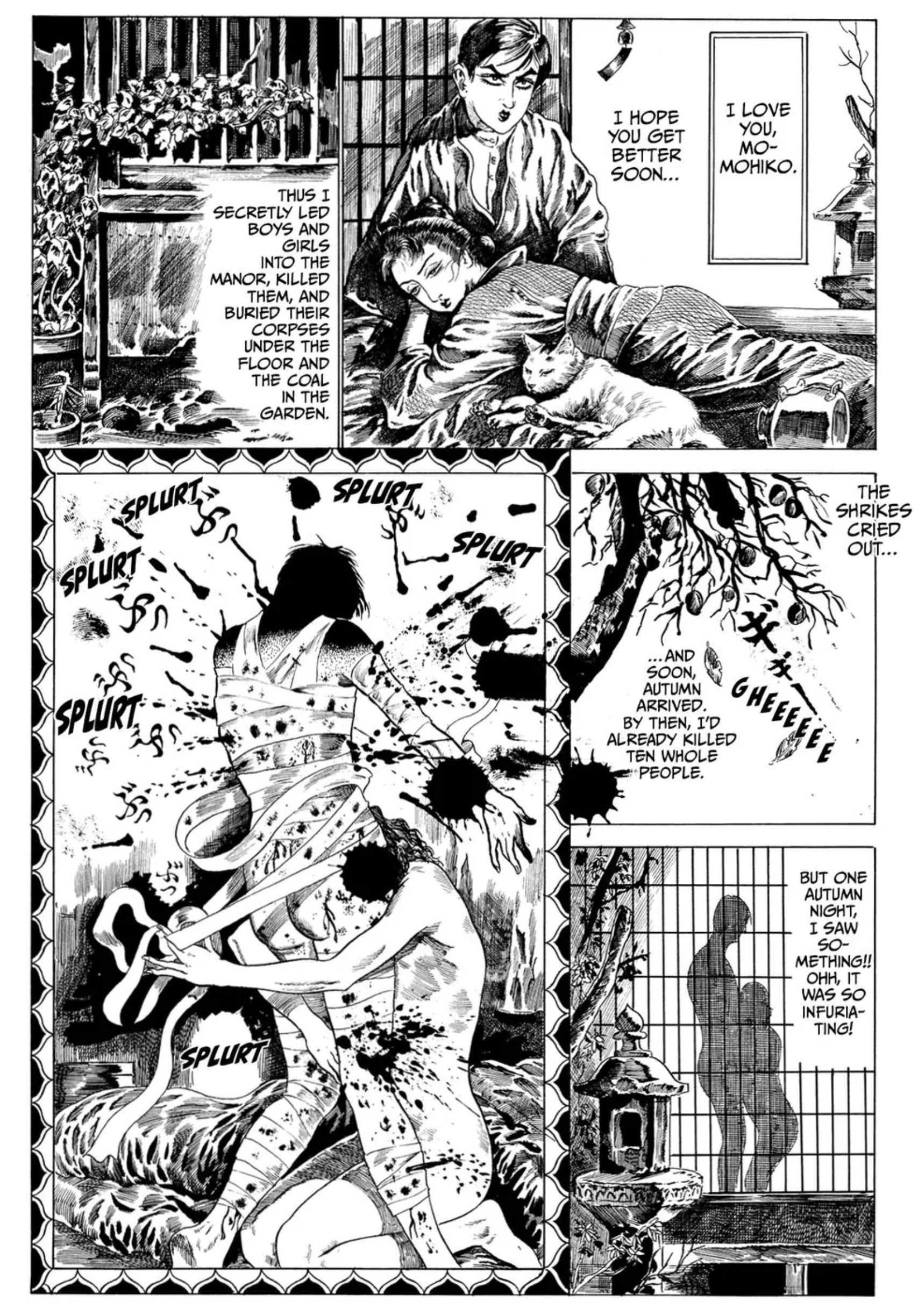

In 1994, gekiga artist Kazuichi Hanawa was arrested for illegal possession of firearms, part of a collection of antique weapons. If you are the sort of reader who knew what gekiga was in the mid 00s, you are already familiar with this story, dramatized in Hanawa's prison memoir Doing Time. As much an itinerary as an autobiography, Doing Time is memorable for Hanawa's meticulous documentation of particular routines, not only of disciplinary actions, but cafeteria food and bathroom schedules. Reading the stories in Light of the Moon, I could not help but find that later work illuminating to Hanawa's approach to the grotesque — in these burlesques of folklore and Japanese imperial imagination, princesses shit, samurai fuck, odour and excretion lurk around every manicured corner. And make no mistake, these corners are manicured — rarely does a large illustration go unadorned with decorative fluorish. Few details escape the weighty elegance of Hanawa's fine hatching and pseudo-engraved penmanship, rendering historical minutia in each wooden slat, each fold of fabric. Hanawa's guro is abjection as envisioned by a fanatic.

Miraculously, this is the second collection of ero guro comics by Hanawa to appear in translation over the past year. The prior collection, Red Night from Breakdown Press and Ryan Holmberg, coheres into a pitch black vision, a weighty sinewy world of shadowy punishment. The stories in Light of the Moon are wider roaming, perhaps even lighter in their gaze, roving across genre and loosening narrative cohesion, a tone accentuated perhaps by the taller trim of this Mansion Press edition, whose lively translation by Dan Luffey is peppered with elegant variations in typeface by letterer Baptiste Neveux. Most of the stories in Light of the Moon originate in the pages of Garo Magazine during its early 70s period of heavily experimental work. The aforementioned defecation tableaux comes from one of the handful of exceptions, “The Pig Woman,” published in S&M Select, a magazine which paired photographs and illustrations of hardcore rope bondage with adult comics. This short, bleak vision of a woman's torture is more narratively compact than the other stories in this book, but its tale of a young girl's frustrated efforts to rescure her mother from the clutches of a nefarious, gross man illustrates a narrative core that is found in all these works — a perfect cycle of torment where any effort to separate victim from aggressor results in the interloper becoming consumed by the very same violence.

Miraculously, this is the second collection of ero guro comics by Hanawa to appear in translation over the past year. The prior collection, Red Night from Breakdown Press and Ryan Holmberg, coheres into a pitch black vision, a weighty sinewy world of shadowy punishment. The stories in Light of the Moon are wider roaming, perhaps even lighter in their gaze, roving across genre and loosening narrative cohesion, a tone accentuated perhaps by the taller trim of this Mansion Press edition, whose lively translation by Dan Luffey is peppered with elegant variations in typeface by letterer Baptiste Neveux. Most of the stories in Light of the Moon originate in the pages of Garo Magazine during its early 70s period of heavily experimental work. The aforementioned defecation tableaux comes from one of the handful of exceptions, “The Pig Woman,” published in S&M Select, a magazine which paired photographs and illustrations of hardcore rope bondage with adult comics. This short, bleak vision of a woman's torture is more narratively compact than the other stories in this book, but its tale of a young girl's frustrated efforts to rescure her mother from the clutches of a nefarious, gross man illustrates a narrative core that is found in all these works — a perfect cycle of torment where any effort to separate victim from aggressor results in the interloper becoming consumed by the very same violence.

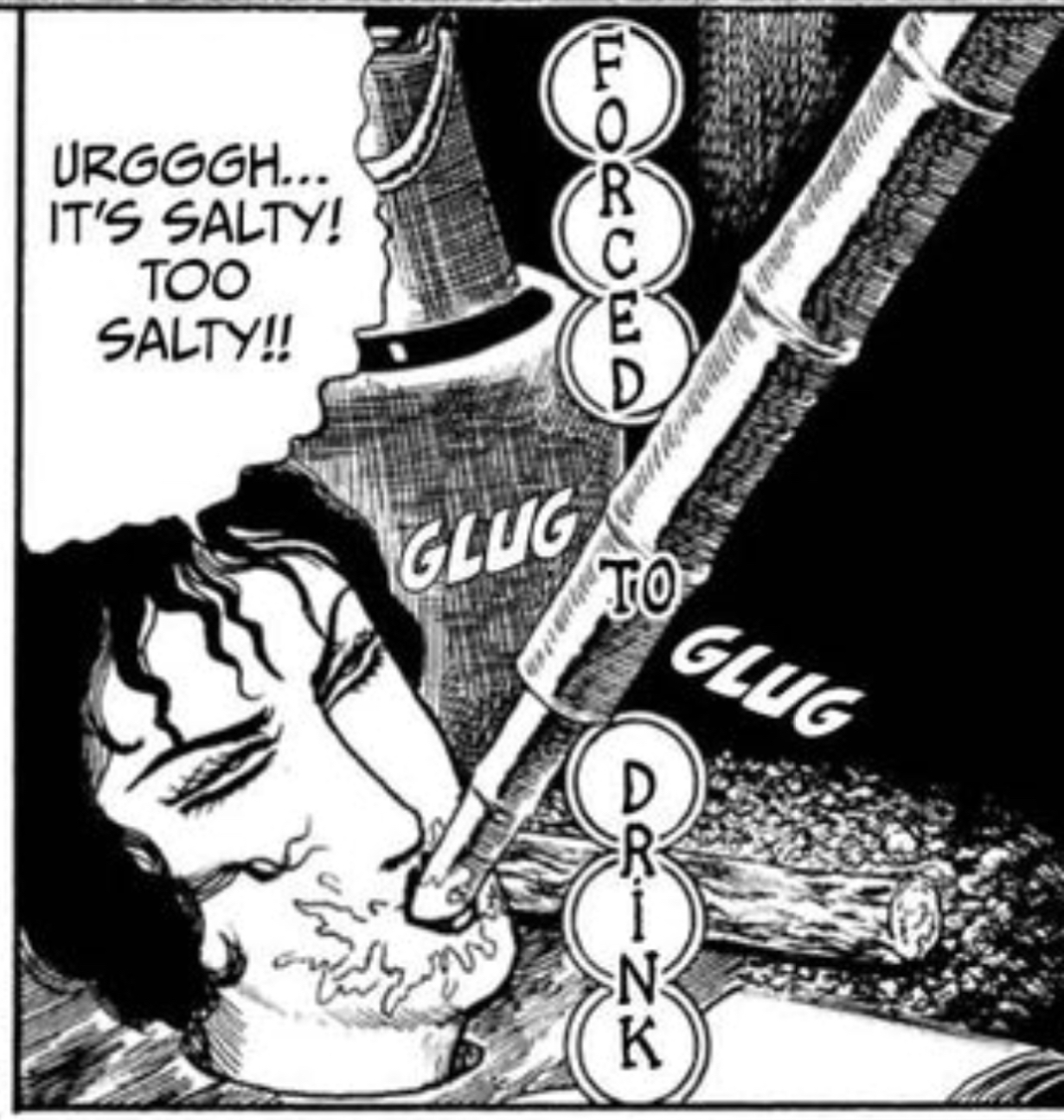

Whether vain or virtuous, man or woman, cruelty between people acts as a whirlpool into which trespassers inevitably succumb. In “Skull Breast,” the titular deformation erupts from a jealous woman who has finally killed the sickly wife of her secret love, the object of her jealousy. The centerpiece of the collection, the trilogy “Retribution,” “Retribution: Hot,” and “Retribution: Cold,” all depict lovers' quarrels which end in maelstroms of violence accompanied by the fury of nature itself, first by a raging river, then by fire, with the later “Manor of Flesh” adding pestilence to natures means of making murder and sadism expand upon itself. In “The Children Who Swear To God” and “The Freak Show,” wide eyed boys confronted with the brutality of nature and society distract themselves by gleefully killing insects, thus joining nature's order. In the deeply odd and delightful “Warring Woman” a woman traps her love under a latrine to prevent him from meeting his death upon conscription into the Japanese military amid the second world war, only for both to perish along with the missing brother's nosy sister in a mailstrom of biting, stabbing, bodily functions and cigarette burns in sensitive places. Ero guro as an artistic movement responds and reacts to the twin snakes of modernity and fascism, suggesting that beneath the sanitary appearance of society lies putrid private lives ruled by violence and amoral urges. Kazuichi Hanawa's stories suggest another possibility - that violence and cruelty are the face of society, that beauty is hidden away and morality is a myth shared in whispers among naive children.

The longest story in the collection, the eponymous “Light of the Moon,” is the oddest of all. Never published in a magazine prior to its collection, “Light of the Moon” is half turn of the century science fiction, half Heian-era folklore. A young boy from an incestuous and impoverished family in drought-ridden Kyoto leaves home to find food to save his family. Meanwhile, a miraculous race of aliens travel to Earth by a flying diesel locomotive, carrying giant grotesque seeds for food. The aliens are mauled by bears immediately upon arrival on Earth, their magnificent abandoned rations growing to fanciful proportions and swallowing people whole through a strangely face-like opening. The starving boy finds the egg and takes it on his travels to avenge his suffering father, only for the egg to fall and shatter. The boy starves to death on the ground. Moonlight falls on a new sprout amid a dense thicket, the boy's bleached skull staring into the night. The narrator assures us that this shaggy dog procession of senseless violence and tragedy has somehow “made the world a better place, isn't that nice?” This deeply odd, narratively meandering yet aesthetically pointed story reveals the depths of Hanawa's artistic virtuosity as well as his true nature as a satirist. Hanawa's narrator is chatty, references other contemporary manga, and asserts the absurdity and futility of his own story. It is a necessary reminder that the ero guro movement which Hanawa's manga helped to resuscitate is in fact Ero Guro Nansensu - Erotic Grotesque Nonsense. Perhaps, as we read through these masterworks of gekiga, we can recall that reducing Japanese history to beautiful women shitting on each other and stabbing people is, in fact, a bit silly. Whether it is a good joke may depend on the reader's patience with aimless stories about aestheticized gender based violence, but there is a lot of joy to be found in the elaborately constructed grand guignol of Hanawa's stories and their inevitable collapse upon themselves into fits of absurdity. Peel back the undeniable mannered granduer of Hanawa's artistry, and the pig woman remains, bound and groaning, violently defecating, somehow beautiful. So stinky!

The post Light Of The Moon appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment